Celtic Britons facts for kids

The Britons were an ancient group of Celtic people who lived in Great Britain for a very long time, starting in the British Iron Age (around 800 BC) and lasting into the Middle Ages. Over time, they developed into different groups we know today, like the Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons (who live in France). They spoke a language called Common Brittonic, which is the ancestor of modern Brittonic languages.

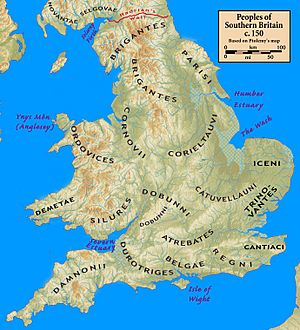

The first written records about the Britons come from ancient Greek and Roman writers during the Iron Age. Celtic Britain was made up of many different tribes and small kingdoms, often protected by large hillforts. The Britons followed an Ancient Celtic religion led by druids. Some southern tribes had strong connections with mainland Europe, especially Gaul (modern France) and Belgica (parts of modern Belgium and France). They even made their own coins.

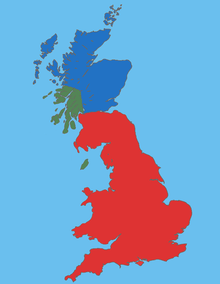

The Roman Empire conquered most of Britain in the 1st century AD, creating the Roman province called Britannia. The Romans tried to invade northern Britain, but the Britons and Caledonians there remained free. Hadrian's Wall became the northern border of the Roman Empire. A new Romano-British culture grew, especially in the southeast, where British Latin was spoken alongside Brittonic. It's not fully clear how the Britons were related to the Picts, who lived outside the Roman Empire in northern Britain. However, most experts now believe the Pictish language was very similar to Common Brittonic.

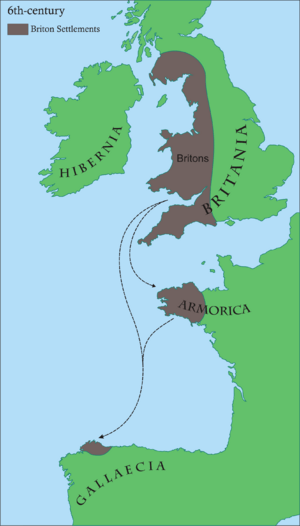

After the end of Roman rule in Britain around 410 AD, the Anglo-Saxons began to settle in eastern and southern Britain. The Britons' culture and language started to break apart. Much of their land slowly became Anglo-Saxon, while smaller parts in the northwest became Gaelic. Some Britons also moved to mainland Europe, creating new communities in Brittany (now part of France), the Channel Islands, and Britonia (now in Spain). By the 11th century, Brittonic-speaking people had split into distinct groups: the Welsh in Wales, the Cornish in Cornwall, the Bretons in Brittany, the Cumbrians in northern England and southern Scotland, and the remaining Picts in northern Scotland. Common Brittonic then developed into the separate Brittonic languages: Welsh, Cumbric, Cornish, and Breton.

Contents

What Does "Britons" Mean?

The earliest known mention of the people of Britain was by Pytheas, a Greek explorer who sailed around the British Isles between 330 and 320 BC. Although his own writings are lost, later Roman writers often referred to them. Pytheas called the people of Britain the Pretanoí or Bretanoí. The Roman name for the Britons was Britanni.

The name *Pritanī likely means "people of the forms." This might be connected to the Latin name Picti (the Picts), which usually means "painted people." The old Welsh name for the Picts was Prydyn.

For many centuries, the English words "Briton" and "British" referred only to these ancient Celtic Britons and their descendants, especially the Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons. However, after the Acts of Union 1707, the term "British" started to be used for all people living in the Kingdom of Great Britain, including the English, Scottish, and some Irish.

The Language of the Britons

The Britons spoke an Insular Celtic language called Common Brittonic. This language was spoken across the island of Britain (modern England, Wales, and Scotland), and on islands like the Isle of Man, Isles of Scilly, Orkney, Hebrides, Isle of Wight, and Shetland. According to old stories, the Celtic speakers who moved to Armorica (modern Brittany in France) after the Romans left Britain brought their language with them, leading to the Breton language, which is similar to Welsh and Cornish.

Common Brittonic came from the Insular branch of the Proto-Celtic language, which arrived in the British Isles around the 7th century BC. Over time, the language changed and split. Some experts group these changes into Western and Southwestern Brittonic languages. Western Brittonic became Welsh in Wales and Cumbric in the "Old North" of Britain (northern England and southern Scotland). The Southwestern dialect became Cornish in Cornwall and Breton in Brittany. Most experts now agree that Pictish also came from Common Brittonic. Welsh and Breton are still spoken today. Cumbric and Pictish died out in the 12th century. Cornish died out by the 19th century but has been brought back to life since the 20th century.

Art and Culture

The La Tène style of art, which defines Celtic art in the Iron Age, arrived late in Britain. But after 300 BC, the ancient Britons seemed to share similar cultural practices with nearby Celtic groups in Europe. However, their artistic styles were quite different. The best period of what's called "Insular La Tène" style, mostly seen in metalwork, was in the century before the Roman conquest and a few decades after. By this time, Celtic styles in mainland Europe were already declining.

The carnyx, a type of trumpet with an animal head, was used by Celtic Britons during battles and ceremonies.

History of the Britons

Where Did the Britons Come From?

Experts have different ideas about when Celtic people and their languages first arrived in Britain. One common idea was that Celtic culture came from the Hallstatt culture in central Europe, reaching Britain in the second half of the first millennium BC. More recently, some historians suggest that Celtic languages developed as a trade language during the Atlantic Bronze Age and then spread eastward. Another idea is that Celtic languages started in Gaul (modern France) and spread to Britain later in the first millennium BC.

In 2021, a big study of ancient DNA found that people migrated into southern Britain during the Bronze Age, between 1300 BC and 800 BC. These migrants were "genetically most similar to ancient individuals from France." Their genes quickly spread through southern Britain, making up about half the ancestry of later Iron Age people in that area. This suggests that the genetic makeup of the population changed through ongoing contact, trade, and small family movements between Britain and Europe over several centuries. This could explain how early Celtic languages spread to Britain.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written around 890 AD, says: "The island Britain is 800 miles long, and 200 miles broad. And there are in the island five nations; English, Welsh (or British), Scottish, Pictish, and Latin. The first inhabitants were the Britons, who came from Armenia, and first peopled Britain southward." (The mention of "Armenia" is likely a mistake for Armorica, an area in northwestern France).

Briton Tribal Groups

The land where the Britons lived was always changing, controlled by many different Brittonic tribes. Before and during the Roman period, their territory likely included all of Great Britain, at least as far north as the Clyde and Forth rivers. If the Picts are included as Brittonic speakers, then it covered the whole island.

The area north of the Firth of Forth was mostly home to the Picts. We don't have much direct evidence of the Pictish language, but place names and Pictish personal names suggest it was related to the Common Brittonic language, not the Goidelic (Gaelic) languages of Ireland and Scotland. The Picts' Irish name, Cruithne, is similar to the Brittonic Priteni. After Gaelic-speaking Celts from Ireland invaded northwestern Britain from the 6th century AD, part of the Pictish land was taken over by the Gaelic kingdoms of Dál Riata and Alba, which later became Scotland.

The Isle of Man, Shetland, the Hebrides, and Orkney were also originally inhabited by Britons. However, they later became Manx and Scots Gaelic speaking territories. The Isles of Scilly and Anglesey remained Brittonic, while the originally Brittonic Isle of Wight was taken by the Anglo-Saxons.

Roman Conquest of Britain

In 43 AD, the Roman Empire invaded Britain. The British tribes fought against the Roman armies for many decades. By 84 AD, the Romans had conquered southern Britain and pushed into Brittonic areas of what would become northern England and southern Scotland. Around 122 AD, the Romans built Hadrian's Wall to protect their northern border. In 142 AD, Roman forces pushed north again and started building the Antonine Wall, but they went back to Hadrian's Wall after only twenty years.

The native Britons south of Hadrian's Wall mostly kept their land but were ruled by the Roman governors. The Brittonic-Pictish Britons north of the wall likely remained fully independent. The Roman Empire controlled "Britannia" until they left around 410 AD, though some parts of Britain had already become free of Roman rule earlier.

Some British influence can be seen in Roman-era artifacts, like the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan. This influence then spread to Ireland in the late Roman and post-Roman periods, affecting the "Celtic" style in early medieval art.

Anglo-Saxon Settlement

About 30 years after the Romans left, Germanic-speaking Anglo-Saxons began to settle on the southeastern coast of Britain, where they started their own kingdoms. At the same time, Gaelic-speaking Scots from Ireland settled on the west coast of Scotland and the Isle of Man.

Meanwhile, some Britons moved to what is now called Brittany and the Channel Islands. They set up their own small kingdoms, and the Breton language developed there. Another Brittonic community, Britonia, was also created in northwestern Spain.

Many of the old Brittonic kingdoms began to disappear in the centuries after the Anglo-Saxon and Scottish Gaelic invasions. Areas like modern East Anglia, East Midlands, North East England, Argyll, and South East England were among the first to fall.

For example, the kingdom of Ceint (modern Kent) fell in 456 AD. Linnuis (in modern Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire) was taken over by 500 AD and became the English Kingdom of Lindsey. Rhegin (modern Sussex and eastern Hampshire) was likely fully conquered by 510 AD. The Isle of Wight fell in 530 AD. Caer Colun (modern Essex) fell by 540 AD. The Gaels arrived in northwestern Britain from Ireland and founded Dal Riata (modern Argyll, Skye, and Iona) between 500 and 560 AD. Deifr (Deira), which included modern Teesside, Wearside, Tyneside, and Lindisfarne, fell to the Anglo-Saxons in 559 AD. Caer Went officially disappeared by 575 AD, becoming the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of East Anglia. Gwent was only partly conquered; its capital, Caer Gloui (Gloucester), was taken in 577 AD, giving Gloucestershire and Wiltshire to the invaders, while the western part remained Brittonic.

Caer Lundein (London, St. Albans, and parts of the Home Counties) fell by 600 AD. Bryneich (Northumbria and County Durham) fell by 605 AD, becoming Anglo-Saxon Bernicia. Caer Celemion (Hampshire and Berkshire) fell by 610 AD. Elmet, a large kingdom in Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Cheshire, was conquered in 627 AD. Pengwern (Staffordshire, Shropshire, Herefordshire, and Worcestershire) was mostly destroyed in 656 AD, with only its western parts in modern Wales remaining Brittonic.

Novant (Galloway and Carrick) was taken over by other Brittonic-Pictish groups by 700 AD. Aeron (Ayrshire) was conquered by the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria by 700 AD.

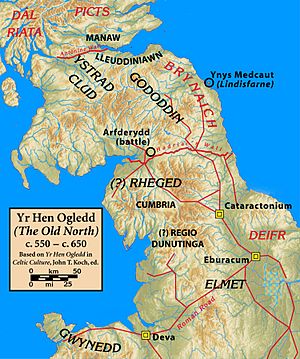

The Old North (Yr Hen Ogledd)

Some Brittonic kingdoms managed to resist these invasions for a while. Rheged (modern Northumberland, County Durham, and parts of southern Scotland) survived into the 8th century AD. Its eastern part peacefully joined the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia–Northumberland by 730 AD, and the west was taken over by the Britons of Ystrad Clud. The kingdom of Gododdin, with its capital at Din Eidyn (modern Edinburgh), lasted until about 775 AD before being divided by Picts, Gaelic Scots, and Anglo-Saxons.

The Kingdom of Cait (modern Caithness, Sutherland, Orkney, and Shetland) was conquered by Gaelic Scots in 871 AD. Dumnonia (Cornwall, Devon, and the Isles of Scilly) was partly conquered in the mid-9th century AD, with most of Devon being taken by the Anglo-Saxons. However, Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly remained Brittonic, becoming the state of Kernow. The Channel Islands, settled by Britons in the 5th century, were attacked by Norse and Danish Vikings in the early 9th century and conquered by the end of that century.

The Kingdom of Ce (modern Marr, Banff, Buchan, Fife, and Aberdeenshire) disappeared soon after 900 AD. Fortriu, the largest Brittonic-Pictish kingdom, fell around 950 AD to the Gaelic Kingdom of Alba (Scotland). Other Pictish kingdoms also fell by the early 11th century.

The Brittonic languages in these areas were eventually replaced by the Old English of the Anglo-Saxons and Scottish Gaelic, though this was likely a slow process. The Brittonic colony of Britonia in Spain also seems to have disappeared soon after 900 AD.

The kingdom of Ystrad Clud (Strathclyde) was a large and powerful Brittonic kingdom in the 'Old North' that lasted until the end of the 11th century. It successfully fought off Anglo-Saxon, Gaelic Scots, and Viking attacks. At its largest, it included modern Strathclyde, Cumbria, and parts of Yorkshire. Strathclyde was the last Brittonic kingdom of the 'Old North' to fall in the 1090s, when it was divided between England and Scotland.

Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany

The Britons also kept control of Wales and Kernow (Cornwall, parts of Devon, and the Isles of Scilly) until the mid-11th century AD. Cornwall was then taken by the English, with the Isles of Scilly following a few years later.

Wales remained free from Anglo-Saxon, Gaelic Scots, and Viking control. It was divided into various Brittonic kingdoms, such as Gwynedd, Powys, Deheubarth, Gwent, and Morgannwg. Some of these Welsh kingdoms initially included lands further east than modern Wales, but by the early 12th century, they were mostly confined to the borders of modern Wales.

By the early 1100s, the Anglo-Saxons and Gaels had become the main cultural force in most of Britain. The language and culture of the native Britons were gradually replaced in those regions, remaining only in Wales, Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly, and Brittany.

Cornwall was largely absorbed by England by the early 1100s, but it kept its unique Brittonic culture and language. Wales and Brittany remained independent for a long time. Brittany joined France in 1532, and Wales joined England in the mid-16th century.

Wales, Cornwall, Brittany, and the Isles of Scilly still have a distinct Brittonic culture, identity, and language today. The Welsh and Breton languages are still widely spoken, and the Cornish language, once almost gone, has been revived since the 20th century. Most place names in Wales, Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly, and Brittany are Brittonic.

In the 19th century, many Welsh farmers moved to Patagonia in Argentina, forming a community called Y Wladfa, which still has over 1,500 Welsh speakers today.

A Brittonic legacy also remains in England, Scotland, and Spain, in the form of many Brittonic place names and geographical names. Examples of Brittonic river names include the Thames, Clyde, Severn, Tyne, Wye, Exe, Dee, Tamar, Tweed, Avon, Trent, Tambre, Navia, and Forth. Many place names in England and Scotland are Brittonic, such as London, Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Carlisle, Caithness, Aberdeen, Dundee, Barrow, Exeter, Lincoln, Dumbarton, Brent, Penge, Colchester, Gloucester, Durham, Dover, Kent, Leatherhead, and York.

Genetics of the Britons

Studies of ancient DNA have helped us understand the Britons better. In 2016, scientists examined the remains of three Iron Age Britons from around 100 BC. Their genetic makeup was typical for people in Northwest Europe. However, these Iron Age individuals were quite different from later Anglo-Saxon samples, who were closely related to Danes and Dutch people.

Another study in 2016 looked at a female Iron Age Briton from between 210 BC and 40 AD. It also examined seven males from Roman Britain (2nd to 4th century AD). Six of these males were identified as native Britons. These native Britons from Roman Britain were genetically similar to the earlier Iron Age female Briton. They also showed close genetic links to modern Celts in the British Isles, especially the Welsh. This suggests that the genetic makeup of people in Britain remained somewhat continuous from the Iron Age through the Roman period. However, they were quite different from the Anglo-Saxon individuals and modern English populations in the area, showing that the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain had a big genetic impact.

See also

In Spanish: Britanos para niños

In Spanish: Britanos para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |