Early modern European cuisine facts for kids

The food and cooking in Europe from about 1500 to 1800 was a mix of old traditions and new ideas that shaped how we eat today. This time is called the Early Modern period.

During this period, Europeans learned about many new foods. This happened because they discovered the New World (the Americas), found new trade routes to Asia, and had more contact with sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.

Before, spices like pepper, cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, and ginger were super expensive. But now, more people could afford them. Also, new plants from the Americas and India arrived, like maize (corn), potatoes, sweet potatoes, chili peppers, cocoa (for chocolate), vanilla, tomatoes, coffee, and tea. These new foods completely changed European cooking!

Even with all these new ideas and trade, people still kept food fresh the old ways. They used drying, salting, smoking, or pickling in vinegar. What people ate also depended on the season. A cookbook from that time even had a recipe for every day of the year! Doctors and chefs still believed foods affected the body's "four humours" – they thought foods could make you feel hot or cold, wet or dry.

Europe became much richer during this time, and this wealth slowly reached everyone. This changed how people ate a lot. The idea of "national cuisine" (like French or Italian food) started to form, but it really took off later. Most cookbooks back then described food for the rich, not for everyday people.

Contents

How Food Changed

The way rich Europeans cooked changed a lot. Old medieval spices like galangal were no longer popular. Recipes still had strong, sour tastes, but by the 1650s, new recipes started to appear, especially in Paris. These new dishes used subtle flavors from herbs and mushrooms.

Meal Times

Today, most people eat three meals a day, but this wasn't common until much later. In Early Modern Europe, people usually ate two meals a day. One was in the morning or around noon, and the other was in the late afternoon or evening. The exact times changed depending on the period and the country.

In Spain and parts of Italy, the morning meal was lighter, and supper was the main meal. But in most of Europe, the first meal of the day was the biggest. Over time, meal times shifted. The first meal, called "dinner" in England, moved from before noon to around 2 or 3 PM by the 1600s. By the late 1700s, it could be as late as 5 or 6 PM. This change meant people needed a midday meal, which was called "luncheon" and later shortened to lunch.

Breakfast wasn't talked about much in old writings. It's not clear if people avoided it or if it just wasn't fancy enough to be mentioned, since most writings were about rich people. Working people probably ate some kind of morning meal, but we don't know exactly when or what it was. Peasants often ate simple foods like "gruels" (a thin porridge) and "pottages" (thick soups). When breakfast became popular, it was usually just coffee, tea, or chocolate. It didn't become a bigger meal in many parts of Europe until the 1800s. In Southern Europe, where supper was the biggest meal, breakfast stayed light, often just coffee or tea with bread.

Foods People Ate

Grains and Breads

For most Europeans, different types of grain were the most important crop. They were the main food for many people. The difference was in the type of grain, its quality, and how it was prepared. Poorer people ate coarse bread with more bran, while richer people enjoyed fine, white wheat flour bread. Wheat was much more expensive than other grains, so many people rarely ate it. Most bread was made from a mix of wheat and other grains.

Grain was the main food in Europe until the 1600s. By then, people were less worried about new foods from the Americas like potatoes and maize (corn). Potatoes became very popular in northern Europe because they were easier to grow and produced more food than wheat. In Ireland, this later caused a huge problem. In the early 1800s, when many people depended almost entirely on potatoes, a plant disease called potato blight ruined the potato crops. This led to a terrible famine that killed over a million people and forced two million more to leave the country.

In places like Scotland, Scandinavia, and northern Russia, the climate wasn't good for growing wheat. So, rye and barley were much more important. Rye was used to bake the dense, dark bread still common in Sweden, Russia, and Finland. Barley was often used to make beer.

Oats were grown but were considered low-status food, often used for animal feed. Millet was used for a long time but mostly disappeared by the 1700s. The Italian dish polenta, once made from millet, later used maize. Pasta was common since the Middle Ages and became more popular, especially in Naples. Rice also became common in places like Italy and Spain, but it was seen as a low-status food. Rich people might have rice pudding sometimes but usually ignored it.

Peas and beans were a big part of poor people's diets in the Middle Ages. They were still important but less so over time, as cereals and potatoes became more common.

Meats

Europeans ate more meat than people in other parts of the world. Over time, more people, even those who weren't rich, started eating more meat. But poor people still mostly relied on eggs, dairy products, and beans for protein. Wild game and fish were eaten in less crowded areas. Richer countries, like England, ate a lot more meat than poorer ones. In some areas, like Germany and Mediterranean countries, ordinary people actually ate less meat starting around 1550, probably because the population was growing.

Fruits and Vegetables

New fruits and vegetables came to Europe during this time. These included the tomato, chili pepper, and pumpkin from the Americas, and the artichoke from the Mediterranean. Also, while wild strawberries existed, the modern garden strawberry was developed in France in the late 1700s from American varieties.

In the 1600s, a new type of building called an orangery became popular. This was like an early greenhouse. It allowed wealthy people to grow or keep fruit plants like oranges, lemons, limes, and even pineapples, even in colder parts of Europe. This meant they could have fresh fruit before refrigerated transport existed.

Fats

You could almost draw a map of Early Modern Europe based on the main cooking fats used: olive oil, butter, and lard. These basic kitchen ingredients hadn't changed since Roman times. However, a period called the Little Ice Age (which happened at the same time as Early Modern Europe) affected the northernmost regions where olives grow. Only olive oil was traded over long distances.

Sugar

Cane sugar, which came from India, was known in Europe during the Middle Ages. It was very expensive and mostly used as a medicine. From the late 1600s, sugar production in the Americas greatly increased to meet Europe's growing demand. By the end of the period, countries with strong navies like England, France, and Spain were eating a lot of sugar. Other parts of Europe used much less. At the same time, people started to separate sweet and savory dishes more clearly. Meat dishes were much less likely to be sweetened than they were in the Middle Ages.

Drinks

Drinking plain water at the table wasn't common in Europe until the Industrial Revolution, when people could make sure drinking water was clean and safe. Almost everyone, except the very poorest, drank mildly alcoholic drinks every day with their meals. In the south, they drank wine; in the north, east, and middle of Europe, they drank beer. Both drinks came in many types and qualities. Northerners who could afford it drank imported wines. Wine was also an important part of religious ceremonies, even for the poor. Ale was the most common type of beer in England for a long time, but it was mostly replaced by beer made with hops from the Low Countries in the 1500s.

Wine

New trade routes and political events led to new wine-making regions and traditions. This period saw the rise of sparkling Champagne, Madeira wine, and fortified Port wine. In England, repeated wars with France made it hard to import French wines. After a treaty in 1703 between England and Portugal, which made Portuguese wines cheaper, England started to rely more on wines from Portugal.

Spirits

The skill of making distilled spirits got much better in Europe during the 1400s. Many of the common spirits we know today were invented and perfected before the 1700s.

Brandy first appeared in Germany in the 1400s. It means "distilled wine." When England and the Netherlands were competing for trade, the Dutch encouraged wine growing outside the Bordeaux area, where the English had strong connections. This led to the regions of Cognac and Armagnac becoming famous for making high-quality brandy. Whisky and schnapps were made in small home stills. Whisky became popular and was sold widely in the 1800s. Gin, a grain liquor flavored with juniper, was invented by the Dutch. Commercial production began in the mid-1600s. It was later improved in England and became very popular among English working classes.

In the "triangular trade" that started in the 1500s and 1600s between Europe, North America, and the Caribbean, rum was a very important product. It was made from molasses and was one of the main things produced from sugar grown on the Caribbean Islands and in Brazil. In Britain, the drink punch also became popular during this time.

Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate

Before the Early Modern period, all social drinks in Europe were alcoholic. But with more contact with Asia, Africa, and the Americas, Europeans discovered tea, coffee, and drinking chocolate. These three drinks became popular social beverages in the 1600s. The new drinks contained caffeine or theobromine, which are mild stimulants and not intoxicating like alcohol. Chocolate was the first to become popular and was a favorite drink of Spanish nobles in the 1500s and early 1600s. All three remained very expensive throughout the Early Modern period.

National Cuisines Begin

As nations started to form in Europe, the basics of what we call "national cuisine" began to appear. Even though many of today's European nations weren't fully formed yet, some things that define a national cuisine started to emerge. These included professional chefs, special kitchens, printed cookbooks, and educated diners.

Italian Cuisine

In Italy, cooking changed from fancy court food to more regional, local dishes by the end of the Early Modern period. At the beginning, the courts of Florence, Rome, Venice, and Ferrara were very important for creating fine Italian cooking. Chefs like Cristoforo di Messisbugo published cookbooks with detailed banquets and many recipes for pies and tarts.

In 1570, Bartolomeo Scappi, who was the personal chef to Pope Pius V, wrote a huge five-volume cookbook called Opera dell'arte del cucinare. It had over 1,000 recipes, information on banquets, and pictures of kitchen tools. This book was important because it was one of the first to focus less on wild game and more on farm animals. It also included recipes for "alternative" cuts of meat like tongue and head. The book also showed how fish and seafood dishes changed with the seasons. Opera even featured an early version of pizza from Naples, but it was sweet, not savory like today's pizza. Turkey and corn also appeared for the first time in an Italian cookbook in this book.

Unlike France, which continued to focus on fancy cooking, Italy started to show a shift towards regional and simpler cooking in the late 1600s. In 1662, the last cookbook on fancy Italian cooking was published. It introduced "ordinary food" (vitto ordinario) to Italian cooking. By the early 1700s, Italian cookbooks started to show the regional differences in Italian food. These books were no longer for professional chefs but for middle-class housewives who cooked at home. These booklets and magazines became more popular and cheaper, so more people could get them.

French Cuisine

In France, changes came from chefs specializing in different cooking skills through guilds. There were guilds for those who supplied raw ingredients and those who prepared them. Guilds specialized in things like baking, pastry making, sauce making, and catering. Because of this specialization, many well-known French dishes started to develop. But it wasn't until the 1600s that French haute cuisine (fancy cooking) began to be written down. François Pierre La Varenne wrote books like Cvisinier françois, and he is known for publishing the first true French cookbook. His recipes showed a change from medieval cooking to new techniques that created lighter dishes and more modest pastries.

During the 1400s and 1500s, French cooking adopted many new foods from the Americas. Even though it took time for them to be used, records show that Catherine de' Medici served sixty-six turkeys at one dinner! The dish called cassoulet has its roots in the discovery of haricot beans from the Americas, which are central to the dish but didn't exist outside the New World before Christopher Columbus's explorations.

It was during this time that coulis (a thick sauce) and roux (a mix of fat and flour used to thicken sauces) first became standard parts of French cooking.

What Came Next

The end of the 1700s (and the Early Modern period) saw big changes that would shape European food as it entered the modern industrial age. First, the first modern public restaurant opened in Paris in the 1780s. After the French Revolution, cooks who used to work for rich families started cooking for new clients, either in other parts of Europe or for the general public in France. This helped restaurants grow. Second, around 1800, Count Rumford designed early versions of a new, efficient kitchen stove, which was different from the old kitchen fireplace. Later, in the 1800s, these stoves were mass-produced and became the new center of kitchens.

Because of colonization and people moving to new places, Early Modern European cuisine became the foundation for the food in the early United States and Canada. It also played a big role in the food traditions of Mexico, Central America, South America, and the West Indies. At the same time, local ingredients and cooking methods, along with food traditions brought by enslaved Africans, and growing national identities, led to new culinary traditions that became different from their European roots.

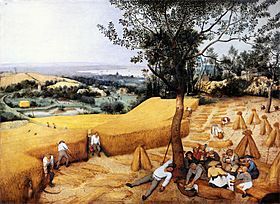

Images for kids

-

Still life with a peacock pie, 1627, by Dutch artist Pieter Claesz. It shows dishes from the 1600s like roast meat, breads, nuts, wine, apples, and dried fruits. There's also a fancy meat pie shaped like a peacock. Lemons were new to the Netherlands and had to be grown in special greenhouses.