Henry III of England facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Henry III |

|

|---|---|

Statue of Henry III on his tomb in Westminster Abbey

|

|

| King of England (more...) | |

| Reign | 28 October 1216 – 16 November 1272 |

| Coronation |

|

| Predecessor | John |

| Successor | Edward I |

| Regents |

See list

|

| Born | 1 October 1207 Winchester Castle, Hampshire, England |

| Died | 16 November 1272 (aged 65) Westminster, London, England |

| Burial | Westminster Abbey, London, England |

| Consort | |

| Issue | |

| House | Plantagenet |

| Father | John, King of England |

| Mother | Isabella, Countess of Angoulême |

Henry III (born October 1, 1207 – died November 16, 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was the King of England. He was also the Lord of Ireland and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. Henry was the son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême. He became king when he was only nine years old. This happened during the First Barons' War.

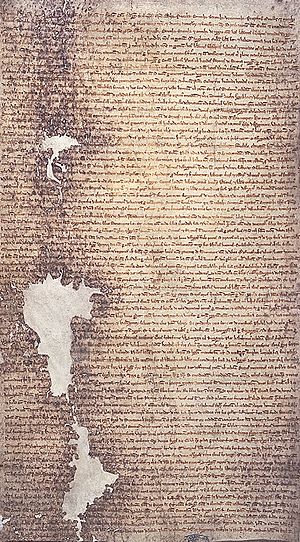

A powerful church leader, Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, said the war against the rebel barons was a holy mission. Henry's army, led by William Marshal, defeated the rebels. They won battles at Lincoln and Sandwich in 1217. Henry promised to follow the Great Charter of 1225. This was a later version of the famous 1215 Magna Carta. It limited the king's power and protected the rights of important nobles.

At first, Henry's rule was guided by Hubert de Burgh and then Peter des Roches. They helped bring back royal power after the war. In 1230, Henry tried to win back lands in France that his father had lost. But this invasion was a big failure. A revolt led by Richard, William Marshal's son, started in 1232. It ended with a peace deal made by the Church.

After this revolt, Henry ruled England himself. He didn't rely on senior ministers as much. He spent a lot of money on his favorite palaces and castles. Henry married Eleanor of Provence and they had five children. He was known for being very religious. He held grand church ceremonies and gave a lot to charity. Henry especially admired Edward the Confessor, making him his patron saint.

Henry also took large amounts of money from the Jewish people in England. This made it very hard for them to do business. As feelings against Jewish people grew stronger, he introduced the Statute of Jewry. This law tried to separate the Jewish community. In 1242, Henry tried again to get back his family's lands in France. He invaded Poitou, but this led to the terrible Battle of Taillebourg. After this, Henry used diplomacy, making friends with Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor.

Henry supported his brother Richard of Cornwall in becoming King of the Romans in 1256. But he couldn't make his own son Edmund Crouchback the king of Sicily, even after spending a lot of money. He planned to go on a crusade to the Holy Land. However, rebellions in Gascony stopped him.

By 1258, many people were unhappy with Henry's rule. This was because his foreign policies were expensive and failed. Also, his half-brothers from Poitou, the Lusignans, were known for causing trouble. Local officials collecting taxes also made people angry. A group of nobles, probably supported by Queen Eleanor, took power. They forced the Poitevins out of England. They also reformed the government with new rules called the Provisions of Oxford.

Henry and the new government made a peace deal with France in 1259. Henry gave up his claims to other lands in France. In return, King Louis IX of France recognized him as the rightful ruler of Gascony. The new government eventually failed. Henry couldn't create a stable government, and England remained unstable.

In 1263, a radical noble named Simon de Montfort took control. This led to the Second Barons' War. Henry convinced Louis of France to support him and gathered an army. In 1264, the Battle of Lewes happened. Henry was defeated and taken prisoner. Henry's oldest son, Edward, escaped. He defeated de Montfort at the Battle of Evesham the next year and freed his father.

At first, Henry took harsh revenge on the rebels. But the Church convinced him to be more forgiving. This led to the Dictum of Kenilworth. Rebuilding the country was slow. Henry had to agree to some changes, like more rules against Jewish people. This was to keep the support of the nobles and the public. Henry died in 1272, and Edward became king. Henry was buried in Westminster Abbey, which he had rebuilt. His body was moved to its current tomb in 1290. Some people said miracles happened after his death, but he was never made a saint. Henry's reign of 56 years was the longest in medieval English history. No English ruler would reign longer until George III in the 1800s.

Henry's Early Life and Family

Henry was born at Winchester Castle on October 1, 1207. He was the oldest son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême. We don't know much about Henry's very early life. A wet nurse named Ellen took care of him in southern England. He was probably close to his mother. Henry had four younger brothers and sisters: Richard, Joan, Isabella, and Eleanor. He also had several older half-siblings. In 1212, Peter des Roches, the bishop of Winchester, became his teacher. Peter made sure Henry received military training.

People didn't write much about how Henry looked. He was probably about 5 feet 6 inches tall. After his death, some accounts said he had a strong build and a drooping eyelid. Historian David Carpenter described Henry as "amiable, easy-going, and sympathetic." He could sometimes get very angry, but mostly he was honest and showed his feelings easily. Religious speeches often made him cry.

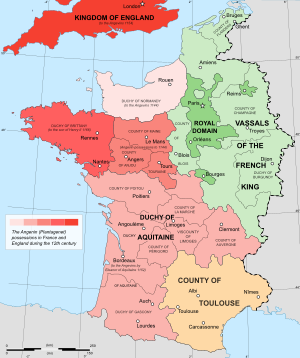

In the early 1200s, the Kingdom of England was part of a huge empire called the Angevin Empire. This empire stretched across Western Europe. Henry was named after his grandfather, Henry II. Henry II had built this vast network of lands. It went from Scotland and Wales, through England, and across the English Channel. It included lands like Normandy and Gascony in France. For many years, the French king was not very powerful. This allowed Henry II and his sons, Richard I and John, to control much of France.

In 1204, King John lost Normandy and other French lands to Philip II of France. This left England with only Gascony and Poitou in France. John raised taxes to pay for wars to get his lands back. But many English nobles became unhappy. John also tried to gain new allies by making England a papal fiefdom. This meant England owed loyalty to the Pope.

In 1215, John and the rebel nobles tried to make peace with the Magna Carta. This treaty would have limited the king's power and stopped the fighting. But neither side followed the rules. John and his loyal nobles rejected the Magna Carta. The First Barons' War began. The rebel nobles were helped by Philip's son, Louis VIII, who wanted to be King of England. The war soon became a stalemate. Neither side could win. King John became sick and died on October 18, 1216. This left nine-year-old Henry as the new king.

Becoming King: Henry's Early Years (1216–1226)

Henry's Coronation

When King John died, Henry was safe at Corfe Castle in Dorset with his mother. On his deathbed, John chose a group of thirteen people to help Henry rule. He also asked that Henry be protected by William Marshal. William was one of England's most famous knights. The loyal leaders decided to crown Henry right away to make his claim to the throne stronger. William made the boy a knight. Then, Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, the Pope's representative in England, oversaw Henry's coronation. This happened at Gloucester Cathedral on October 28, 1216.

The Archbishops of Canterbury and York were not there. So, Sylvester, Bishop of Worcester, and Simon, Bishop of Exeter, anointed Henry. Peter des Roches crowned him. The royal crown had been lost or sold during the civil war. So, a simple gold crown belonging to Queen Isabella was used instead. Henry had a second coronation at Westminster Abbey on May 17, 1220.

The young king faced a difficult situation. More than half of England was controlled by rebels. Most of his father's lands in Europe were still held by the French. But Henry had strong support from Cardinal Guala. Guala wanted Henry to win the civil war and punish the rebels. Guala worked to strengthen the ties between England and the Pope. At the coronation, Henry showed respect to the Pope. He recognized Pope Honorius III as his feudal lord. Honorius declared Henry his vassal and ward. This meant the Pope's representative had full power to protect Henry and his kingdom. Henry also took the cross, meaning he declared himself a crusader. This gave him special protection from Rome.

Two important nobles were candidates to lead Henry's government. The first was William. He was old, but known for his loyalty. He could help the war with his own men and supplies. The second was Ranulf de Blondeville, 6th Earl of Chester. He was one of the most powerful loyal nobles. William wisely waited until both Guala and Ranulf asked him to take the job. Then he took power. William then made Peter des Roches Henry's guardian. This allowed William to focus on leading the army.

Ending the Barons' War

The war was not going well for Henry's supporters. The new government even thought about retreating to Ireland. Prince Louis and the rebel nobles were also struggling to make progress. Louis controlled Westminster Abbey, but he couldn't be crowned king. This was because the English Church and the Pope supported Henry. King John's death had eased some of the rebels' anger. Royal castles were still holding out in rebel-held areas. To take advantage of this, Henry encouraged rebel nobles to rejoin his side. He offered to give back their lands. He also reissued a version of the Magna Carta. This version removed some clauses, especially those the Pope didn't like. But this move didn't work, and opposition to Henry's government grew stronger.

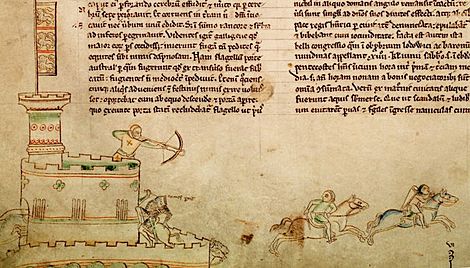

In February, Louis sailed to France to get more soldiers. While he was gone, arguments broke out between Louis's French and English followers. Cardinal Guala declared that Henry's war against the rebels was a religious crusade. This caused many rebels to switch sides. The war began to turn in Henry's favor. Louis returned in late April and restarted his campaign. He split his forces into two groups. One went north to attack Lincoln Castle. The other stayed south to capture Dover Castle. When William Marshal learned Louis had split his army, he decided to risk everything on one big battle. William marched north and attacked Lincoln on May 20. He entered through a side gate and took the city in fierce street fights. They looted the buildings. Many important rebels were captured. Historian David Carpenter calls this battle "one of the most decisive in English history."

After Lincoln, Henry's campaign slowed down. It only started again in late June after the winners had arranged to ransom their prisoners. Meanwhile, support for Louis's campaign was shrinking in France. He decided the war in England was lost. Louis negotiated with Cardinal Guala. He would give up his claim to the English throne. In return, his followers would get their lands back. Any punishments from the Church would be lifted. Henry's government would also promise to enforce the Magna Carta. This proposed agreement quickly fell apart. Some of Henry's supporters felt it was too generous to the rebels. This was especially true for the churchmen who had joined the rebellion. Without a deal, Louis stayed in London with his remaining forces.

On August 24, 1217, a French fleet arrived off the coast of Sandwich. It brought Louis more soldiers, siege engines, and supplies. Hubert de Burgh, Henry's chief justice, sailed to stop it. This led to the Battle of Sandwich. De Burgh's fleet scattered the French ships. They captured their main ship, commanded by Eustace the Monk. Eustace was quickly executed. When Louis heard the news, he started new peace talks.

Henry, Isabella, Louis, Guala, and William agreed on the final Treaty of Lambeth. This was also called the Treaty of Kingston. It was signed on September 12 and 13. The treaty was similar to the first peace offer. But it excluded the rebel churchmen. Their lands and positions remained lost. Louis accepted a gift of £6,666 to leave England faster. He also promised to try to convince King Philip to return Henry's lands in France. Louis left England as agreed. He then joined the Albigensian Crusade in southern France.

Rebuilding Royal Power

After the civil war, Henry's government had to rebuild royal power. This was needed across large parts of the country. By late 1217, many former rebels ignored royal orders. Even Henry's loyal supporters kept strong control over royal castles. Illegal forts, called adulterine castles, had appeared everywhere. The system of county sheriffs had broken down. This meant the government couldn't collect taxes or royal income. The powerful Welsh Prince Llywelyn was a major threat in Wales.

William Marshal had won the war, but he struggled to restore royal power. This was partly because he couldn't offer many rewards. Loyal nobles expected to be rewarded. William tried to enforce the Crown's traditional rights. These included approving marriages and guardianships. But he had little success. Still, he managed to restart the royal courts and the royal exchequer (treasury). The government issued the Charter of the Forest. This tried to improve how royal forests were managed. The government and Llywelyn agreed to the Treaty of Worcester in 1218. But its generous terms showed how weak the English Crown was. Llywelyn became Henry's chief justice across Wales.

Henry's mother couldn't find a role in the government. She returned to France in 1217. She married Hugh X de Lusignan, a powerful noble from Poitou. William Marshal became sick and died in April 1219. A new government was formed. It included three main ministers: Pandulf Verraccio, the new Pope's representative; Peter des Roches; and Hubert de Burgh, a former chief justice. A great council of nobles at Oxford appointed them. Their government relied on these councils for power. Hubert and des Roches were rivals. Hubert had support from English nobles. Des Roches was backed by nobles from royal lands in Poitou. Hubert moved against des Roches in 1221. He accused him of treason and removed him as the King's guardian. The Bishop left England for the crusades. Pandulf was called back to Rome the same year. This left Hubert as the most powerful person in Henry's government.

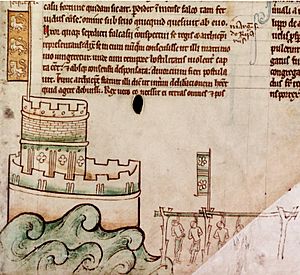

At first, the new government had little success. But in 1220, Henry's government started to do better. The Pope allowed Henry to be crowned a second time. They used new royal symbols. The new coronation was meant to show the King's power. Henry promised to bring back the Crown's powers. The nobles swore they would return royal castles and pay their debts to the Crown. If they didn't, they faced being excommunicated. Hubert, with Henry, went to Wales to stop Llywelyn in 1223. In England, Henry's forces slowly took back his castles. The effort against the remaining stubborn nobles came to a head in 1224. This was the siege of Bedford Castle. Henry and Hubert attacked it for eight weeks. When it finally fell, almost all the soldiers inside were killed. The castle was carefully destroyed.

Meanwhile, Louis VIII of France joined forces with Hugh de Lusignan. They invaded Poitou and then Gascony. Henry's army in Poitou was small and lacked support. Many Poitou nobles felt abandoned during Henry's younger years. So, the province quickly fell. It became clear that Gascony would also fall without help from England. In early 1225, a great council approved a tax of £40,000. This was to send an army. The army quickly retook Gascony. In exchange for their support, the nobles demanded that Henry reissue the Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest. This time, the King said the charters were issued by his own "spontaneous and free will." He confirmed them with the royal seal. This gave the new Great Charter and the Charter of the Forest of 1225 much more power. The nobles expected the King to follow these clear charters. They expected him to be subject to the law and guided by their advice.

Henry's Rule: Challenges and Changes (1227–1258)

Trying to Regain French Lands

Henry officially took control of his government in January 1227. Some people at the time argued he was still legally a minor. He wouldn't be 21 until the next year. The King greatly rewarded Hubert de Burgh for his help. He made him the Earl of Kent and gave him many lands. Even though he was now an adult, Henry was still heavily influenced by his advisers. For the first few years, he kept Hubert as his chief justice for life.

The future of Henry's family lands in France was still unclear. Getting these lands back was very important to Henry. He used phrases like "reclaiming his inheritance" and "restoring his rights" in his letters. The French kings had a growing financial and military advantage over Henry. Even under King John, the French king had more resources. But since then, the difference had grown even more. The French king's yearly income almost doubled between 1204 and 1221.

Louis VIII died in 1226. His 12-year-old son, Louis IX, became king. He was supported by a government of regents. The young French king was in a much weaker position than his father. Many French nobles still had ties to England and opposed him. This led to several revolts across France. Because of this, in late 1228, some Norman and Angevin rebels asked Henry to invade. They wanted him to reclaim his lands. Peter I, Duke of Brittany, openly rebelled against Louis and pledged loyalty to Henry.

Henry's plans for an invasion were slow. When he finally arrived in Brittany with an army in May 1230, the campaign didn't go well. Perhaps on Hubert's advice, the King decided not to fight the French. He didn't invade Normandy. Instead, he marched south into Poitou. He fought without much success over the summer. Finally, he safely moved on to Gascony. He made a truce with Louis until 1234. He returned to England having achieved nothing. Historian Huw Ridgeway called the trip a "costly fiasco."

Richard Marshal's Rebellion

Henry's chief minister, Hubert, lost power in 1232. His old rival, Peter des Roches, returned to England from the crusades in August 1231. Peter joined forces with Hubert's growing number of political enemies. He told Henry that Hubert had wasted royal money and lands. He also blamed Hubert for riots against foreign churchmen. Hubert sought safety in Merton Priory. But Henry had him arrested and put in the Tower of London. Des Roches took over the King's government. He was supported by the Poitevin nobles in England. They saw this as a chance to get back lands they had lost to Hubert's followers.

Des Roches used his new power to take away his opponents' estates. He did this without using the courts or legal process. Powerful nobles, like Richard Marshal, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, complained more and more. They argued that Henry was not protecting their legal rights, as stated in the 1225 charters. A new civil war broke out between des Roches and Richard's followers. Des Roches sent armies into Richard's lands in Ireland and South Wales. In response, Richard allied with Prince Llywelyn. His own supporters rebelled in England. Henry couldn't win a clear military advantage. He became worried that Louis of France might invade Brittany while he was busy at home. The truce there was about to end.

Edmund of Abingdon, the Archbishop of Canterbury, stepped in during 1234. He held several great councils. He advised Henry to fire des Roches. Henry agreed to make peace. But before the talks finished, Richard died from battle wounds. His younger brother Gilbert inherited his lands. The final agreement was confirmed in May. Henry was praised for humbly accepting the slightly embarrassing peace. Meanwhile, the truce with France in Brittany finally ended. Henry's ally, Duke Peter, faced new military pressure. Henry could only send a small army to help. Brittany fell to Louis in November. For the next 24 years, Henry ruled the kingdom himself. He did not use senior ministers.

Henry's Time as King

How Henry Ruled England

In England, the government used to be run by several important officials. These were powerful, independent nobles. Henry changed this. He left the position of chief justice empty. He made the chancellor a less important role. A small royal council was created, but its job wasn't clear. Henry and his close advisers made decisions about appointments, rewards, and policies. They didn't use the larger councils from his early years. This made it much harder for people outside Henry's inner circle to influence decisions. It was also harder to complain about problems, especially against the King's friends.

Henry believed kings should rule England with dignity. He wanted lots of ceremonies and church rituals. He thought his earlier kings had let the Crown's status drop. He tried to fix this during his reign. The civil war when Henry was young deeply affected him. He chose the Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor as his patron saint. He hoped to be like Edward, who brought peace and unity to England. Henry tried to use his royal power gently. He hoped to calm the angry nobles and keep peace in England.

So, even though he focused on royal power, Henry's rule was quite limited. He generally followed the charters. These prevented the King from taking illegal actions against nobles. This included fines and taking their property, which was common under King John. The charters didn't deal with important issues like choosing royal advisers or giving out rewards. They also didn't have a way to be enforced if the King ignored them. Henry's rule became relaxed and careless. This led to less royal power in the regions. Eventually, his authority at court collapsed. He didn't always apply the charters consistently. This made many nobles unhappy, even those who supported him.

The word "parliament" first appeared in the 1230s and 1240s. It described large meetings of the royal court. Parliament meetings were held regularly during Henry's reign. They were used to agree on raising taxes. In the 1200s, taxes were usually one-time payments on movable goods. They were meant to help the King's normal income for specific projects. During Henry's reign, counties started sending regular groups to these parliaments. These groups represented a wider range of people than just the main nobles.

Despite the various charters, royal justice was not always fair. It was often based on what was politically needed at the moment. Sometimes, action would be taken to fix a noble's complaint. Other times, the problem would just be ignored. The royal eyres, which were courts that traveled the country to provide local justice, had little power. These courts were usually for smaller nobles and gentry who had complaints against the major lords. This allowed the major nobles to control the local justice system.

The power of royal sheriffs also decreased during Henry's reign. They were often lesser men chosen by the treasury. They focused on making money for the King. Their strong efforts to collect fines and debts made them very unpopular among the common people. Unlike his father, Henry did not take advantage of the large debts nobles often owed the Crown. He was slow to collect any money due to him.

Life at Court

The royal court was made up of Henry's trusted friends. These included Richard de Clare, 6th Earl of Gloucester; the brothers Hugh Bigod and Roger Bigod, 4th Earl of Norfolk; Humphrey de Bohun, 2nd Earl of Hereford; and Henry's brother, Richard. Henry wanted his court to bring together his English and European subjects. It included the French knight Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester. Simon had married Henry's sister Eleanor. Later, many of Henry's relatives from Savoy and Lusignan also joined the court. The court followed European styles and traditions. It was heavily influenced by Henry's family traditions from Anjou. French was the spoken language. The court had close ties to the royal courts of France, Castile, the Holy Roman Empire, and Sicily. Henry supported the same writers as other European rulers.

Henry traveled less than previous kings. He wanted a calm, quieter life. He stayed at each of his palaces for long periods before moving. Perhaps because of this, he paid more attention to his palaces and homes. According to architectural historian John Goodall, Henry was "the most obsessive patron of art and architecture ever to have occupied the throne of England." Henry expanded the royal complex at Westminster in London, one of his favorite homes. He rebuilt the palace and the abbey. This cost almost £55,000. He spent more time in Westminster than any king before him. He helped shape London into England's capital city.

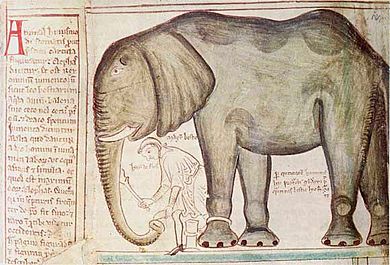

He spent £58,000 on his royal castles. He did major work at the Tower of London, Lincoln, and Dover. Both the military defenses and the living areas of these castles were greatly improved. A huge renovation of Windsor Castle created a lavish palace. Its style and details inspired many later designs in England and Wales. The Tower of London was expanded to be a strong fortress with large living quarters. However, Henry mainly used the castle as a safe place during war or civil unrest. He also kept a menagerie (animal collection) at the Tower. This tradition was started by his father. His exotic animals included an elephant, a leopard, and a camel.

Henry changed the silver coin system in England in 1247. He replaced the old Short Cross silver pennies with a new Long Cross design. Because of the initial costs, he needed his brother Richard's financial help for this change. But the new coinage happened quickly and efficiently. Between 1243 and 1258, the King collected two large hoards, or stockpiles, of gold. In 1257, Henry urgently needed to spend the second gold hoard. Instead of selling the gold quickly and lowering its value, he decided to introduce gold pennies in England. This followed a popular trend in Italy. The gold pennies looked like the gold coins issued by Edward the Confessor. But the coins were valued too high. This led to complaints from the City of London, and the idea was eventually dropped.

Henry's Religious Beliefs

Henry was known for showing his strong religious faith in public. He seemed to be truly devout. He encouraged rich, fancy Church services. He went to mass at least once a day, which was unusual for the time. He gave generously to religious causes. He paid for 500 poor people to be fed every day and helped orphans. He fasted before celebrating Edward the Confessor's feast days. He may have washed the feet of lepers. Henry often went on pilgrimages. He especially visited the abbeys of Bromholm, St Albans, and Walsingham Priory. However, he sometimes used pilgrimages as an excuse to avoid dealing with urgent political problems.

Henry shared many of his religious views with Louis of France. The two kings seemed to compete a little in their piety. Towards the end of his reign, Henry may have started curing people with scrofula (often called "the King's evil") by touching them. He might have been copying Louis, who also did this. Louis had a famous collection of Passion Relics in the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. He paraded the Holy Cross through Paris in 1241. Henry got the Relic of the Holy Blood in 1247. He marched it through Westminster to be placed in Westminster Abbey. He promoted Westminster Abbey as an alternative to the Sainte-Chapelle.

Henry especially supported the mendicant orders (friars). His confessors were Dominican friars. He built friar houses in Canterbury, Norwich, Oxford, Reading, and York. He helped find valuable space for new buildings in already crowded towns. He supported the military crusading orders. He became a patron of the Teutonic Order in 1235. The new universities of Oxford and Cambridge also received royal attention. Henry strengthened and regulated their powers. He encouraged scholars to move from Paris to teach there. A rival school at Northampton was declared by the King to be just a school, not a true university.

The support Henry received from the Pope in his early years had a lasting effect on him. He strongly defended the Church throughout his reign. In the 1200s, Rome was the center of the Church across Europe. It was also a political power in central Italy, threatened by the Holy Roman Empire. During Henry's reign, the Pope's government grew strong and centralized. It was supported by payments given to churchmen working in Rome. Tensions grew between this practice and the needs of local churchgoers. This was seen in the dispute between Robert Grosseteste, the bishop of Lincoln, and the Pope in 1250.

The Scottish Church became more independent of England during this time. However, the Pope's representatives helped Henry still influence its activities from afar. Pope Innocent IV's attempts to raise money began to face opposition within the English Church. In 1240, the Pope's messenger collected taxes to pay for the Pope's war with Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. This led to protests. But Henry and the Pope eventually overcame them. In the 1250s, Henry's taxes for crusades faced similar resistance.

Policies Towards Jewish People

The Jewish people in England were seen as the King's property. They had traditionally been a source of cheap loans and easy taxes. In return, they received royal protection against hatred. Jewish people had suffered greatly during the First Barons' War. But during Henry's early years, the community thrived. It became one of the wealthiest in Europe. This was mainly because Henry's government protected Jewish people and encouraged lending. This was for financial gain, as they profited greatly from a strong Jewish community. Their policy went against the Pope's instructions. The Pope had issued strong anti-Jewish rules at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. William Marshal continued his policy despite complaints from the Church.

In 1239, Henry introduced different policies. He might have been trying to copy Louis of France. Jewish leaders across England were imprisoned. They were forced to pay fines equal to a third of their goods. Any unpaid loans were to be canceled. More huge demands for cash followed. For example, £40,000 was demanded in 1244. About two-thirds of this was collected within five years. This destroyed the Jewish community's ability to lend money. The financial pressure Henry put on Jewish people made them demand loan repayments. This fueled anti-Jewish anger. A particular complaint among smaller landowners, like knights, was the sale of Jewish bonds. Richer nobles and Henry's friends bought these bonds. They used them to take lands from smaller landowners if they couldn't pay their debts.

Henry had built the Domus Conversorum in London in 1232. This was to help Jewish people convert to Christianity. These efforts increased after 1239. As many as 10 percent of Jewish people in England had converted by the late 1250s. This was largely due to their worsening economic situation. Many anti-Jewish stories, including tales of child sacrifice, spread between the 1230s and 1250s. This included the story of "Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln" in 1255. This event is important because it was the first such accusation supported by the King. Henry ordered the execution of Copin, who had confessed to the murder in exchange for his life. He also sent 91 Jewish people to the Tower of London. Eighteen were executed, and their property was taken by the Crown. At the time, the Jewish people were indebted to Richard of Cornwall. He intervened to release the Jewish people who were not executed. He probably had the support of Dominican or Franciscan friars.

Henry passed the Statute of Jewry in 1253. This law tried to stop the building of synagogues. It also tried to force Jewish people to wear Jewish badges, following Church rules. It's unclear how much the King actually enforced this law. By 1258, Henry's policies towards Jewish people were seen as confusing. They were also increasingly unpopular among the nobles. Overall, Henry's policies up to 1258—heavy Jewish taxation, anti-Jewish laws, and propaganda—caused a very important and negative change.

Henry's Personal Rule (1234–1258)

Henry's Marriage and Family

Henry looked into many possible wives when he was young. But they all proved unsuitable because of European and English politics. In 1236, he finally married Eleanor of Provence. She was the daughter of Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Provence, and Beatrice of Savoy. Eleanor was well-mannered, educated, and spoke well. But the main reason for the marriage was political. Henry hoped to create valuable alliances with rulers in southern France. Over the years, Eleanor became a strong and determined politician. Historians Margaret Howell and David Carpenter describe her as "more combative" and "far tougher and more determined" than her husband.

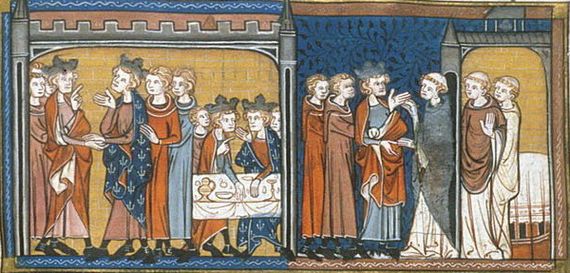

The marriage contract was confirmed in 1235. Eleanor traveled to England to meet Henry for the first time. They were married at Canterbury Cathedral in January 1236. Eleanor was crowned queen at Westminster shortly after. It was a grand ceremony planned by Henry. There was a big age difference between them. Henry was 28, and Eleanor was only 12. But historian Margaret Howell notes that the King "was generous and warm-hearted and prepared to lavish care and affection on his wife."

Henry gave Eleanor many gifts. He paid personal attention to setting up her household. He also included her fully in his religious life. This included his devotion to Edward the Confessor. One story says that in 1238, while they were at Woodstock Palace, Henry III survived an assassination attempt. This was because he wasn't in his room when the attacker broke in.

At first, people worried the Queen might not have children. But Henry and Eleanor had five children together. In 1239, Eleanor gave birth to their first child, Edward. He was named after the Confessor. Henry was overjoyed. He held huge celebrations. He gave generously to the Church and the poor. This was to ask God to protect his young son. Their first daughter, Margaret, was born in 1240. She was named after Eleanor's sister. Her birth also had celebrations and donations to the poor. The third child, Beatrice, was named after Eleanor's mother. She was born in 1242 during a military campaign in Poitou.

Their fourth child, Edmund, arrived in 1245. He was named after the 9th-century saint. Henry was worried about Eleanor's health. He donated large amounts of money to the Church throughout the pregnancy. A third daughter, Katherine, was born in 1253. But she soon became ill. It might have been a degenerative disorder like Rett syndrome. She couldn't speak. She died in 1257, and Henry was heartbroken. His children spent most of their childhood at Windsor Castle. He seemed very attached to them. He rarely spent long periods away from his family.

After Eleanor's marriage, many of her relatives from Savoy joined her in England. At least 170 Savoyards arrived after 1236. They came from Savoy, Burgundy, and Flanders. This included Eleanor's uncles, Archbishop Boniface of Canterbury and William of Savoy. William was Henry's chief adviser for a short time. Henry arranged marriages for many of them into the English nobility. This initially caused problems with the English nobles. They didn't like land going to foreigners. The Savoyards were careful not to make things worse. They became more integrated into English noble society. They formed an important power base for Eleanor in England.

Troubles in Poitou and the Lusignans

In 1241, nobles in Poitou, including Henry's stepfather Hugh de Lusignan, rebelled against Louis of France. The rebels had counted on help from Henry. But he lacked support in England and was slow to gather an army. He didn't arrive in France until the next summer. His campaign was hesitant. It was further hurt when Hugh switched sides and rejoined Louis. On May 20, Henry's army was surrounded by the French at Taillebourg. Henry's brother Richard convinced the French to delay their attack. The King used this chance to escape to Bordeaux.

Simon de Montfort, who fought well to protect the army during the retreat, was furious. He told Henry that he should be locked up like the 10th-century king Charles the Simple. The Poitou rebellion collapsed. Henry made a new five-year truce. His campaign had been a terrible failure and cost over £80,000.

After the revolt, French power spread throughout Poitou. This threatened the Lusignan family's interests. In 1247, Henry encouraged his relatives to travel to England. They were given large estates, mostly at the expense of English nobles. More Poitevins followed. About 100 settled in England. Around two-thirds of them were given significant incomes of £66 or more by Henry. Henry encouraged some to help him in Europe. Others worked as soldiers for hire and diplomatic agents. Some fought for Henry in European wars. Many were given estates along the disputed Welsh Marches or in Ireland. There, they protected the borders. For Henry, this group was an important symbol of his hope to one day reconquer Poitou and his other French lands. Many of the Lusignans became close friends with his son Edward.

The presence of Henry's extended family in England caused controversy. Writers at the time, especially Roger de Wendover and Matthew Paris, complained about the number of foreigners. Historian Martin Aurell notes the anti-foreigner tone of their comments. The term "Poitevins" was loosely used for this group, even though many came from other parts of France. By the 1250s, there was strong rivalry between the established Savoyards and the newly arrived Poitevins. The Lusignans began to break the law without punishment. They pursued personal grudges against other nobles and the Savoyards. Henry did little to stop them. By 1258, the general dislike of the Poitevins had turned into hatred. Simon de Montfort was one of their strongest critics.

Relations with Scotland, Wales, and Ireland

Henry's power in Wales grew stronger during the first twenty years of his personal rule. After Llywelyn the Great died in 1240, Henry's influence in Wales expanded. Three military campaigns were carried out in the 1240s. New castles were built. Royal lands in the County of Chester were expanded. This increased Henry's control over the Welsh princes. Dafydd, Llywelyn's son, resisted these attacks. But he died in 1246. Henry confirmed the Treaty of Woodstock the next year with Owain and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. They were Llywelyn the Great's grandsons. Under the treaty, they gave land to the King. But they kept the main part of their princedom in Gwynedd.

In South Wales, Henry slowly extended his power across the region. But the campaigns were not very strong. The King did little to stop the Marcher territories along the border from becoming more independent. In 1256, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd rebelled against Henry. Widespread violence spread across Wales. Henry promised a quick military response but did not follow through.

Ireland was important to Henry. It was a source of royal income. An average of £1,150 was sent from Ireland to the Crown each year during the middle of his reign. It was also a source of estates that could be given to his supporters. The major landowners looked to Henry's court for political leadership. Many also owned estates in Wales and England. The 1240s saw big changes in land ownership. This was due to deaths among the nobles. This allowed Henry to give Irish lands to his supporters.

In the 1250s, the King gave many land grants along the Irish border to his supporters. This created a buffer zone against the native Irish. The local Irish kings faced more harassment as English power grew. These lands were often not profitable for the nobles to hold. English power reached its peak under Henry for the medieval period. In 1254, Henry gave Ireland to his son, Edward. The condition was that it would never be separated from the Crown.

Henry kept peace with Scotland during his reign. He was the feudal lord of Alexander II. Henry believed he had the right to interfere in Scottish affairs. He brought up his authority with the Scottish kings at important times. But he lacked the desire or resources to do much more. Alexander had taken parts of northern England during the First Barons' War. But he had been excommunicated and forced to retreat. Alexander married Henry's sister Joan in 1221. After he and Henry signed the Treaty of York in 1237, Henry had a secure northern border. Henry knighted Alexander III before the young king married Henry's daughter Margaret in 1251. Despite Alexander's refusal to show loyalty to Henry for Scotland, the two had a good relationship. Henry had Alexander and Margaret rescued from Edinburgh Castle. They were imprisoned there by a rebellious Scottish noble in 1255. He took more steps to manage Alexander's government during the rest of his younger years.

Henry's European Plans

Henry had no more chances to win back his lands in France after his military campaign failed at the Battle of Taillebourg. Henry's resources were too small compared to those of the French King. By the late 1240s, it was clear that King Louis was the most powerful ruler in France. Henry instead adopted what historian Michael Clanchy called a "European strategy." He tried to regain his lands in France through diplomacy, not force. He built alliances with other states willing to put military pressure on the French King. Henry especially tried to befriend Frederick II. He hoped Frederick would turn against Louis or let his nobles join Henry's campaigns. Because of this, Henry focused more and more on European politics rather than English affairs.

Crusading was a popular cause in the 1200s. In 1248, Louis joined the unsuccessful Seventh Crusade. First, he made a new truce with England. He also got promises from the Pope that he would protect his lands from any attack by Henry. Henry might have joined this crusade himself. But the rivalry between the two kings made this impossible. After Louis's defeat at the Battle of Al Mansurah in 1250, Henry announced he would go on his own crusade to the Holy Land. He started making plans for travel with friendly rulers around the Holy Land. He made his royal household save money. He arranged for ships and transport. He seemed almost too eager to go. Henry's plans showed his strong religious beliefs. But they also stood to give him more international respect when arguing for the return of his French lands.

Henry's crusade never left. He was forced to deal with problems in Gascony. His lieutenant, Simon de Montfort, had used harsh policies there. This caused a violent uprising in 1252. King Alfonso X of neighboring Castile supported it. The English court was split. Simon and Eleanor argued that the Gascons were to blame. Henry, backed by the Lusignans, blamed Simon's poor judgment. Henry and Eleanor argued over this and didn't make up until the next year. Henry had to step in himself. He carried out an effective, though expensive, campaign with the Lusignans' help. He stabilized the province. Alfonso signed a treaty of alliance in 1254. Gascony was given to Henry's son Edward. Edward married Alfonso's half-sister Eleanor. This brought a long-lasting peace with Castile.

On the way back from Gascony, Henry met Louis for the first time. Their wives arranged the meeting. The two kings became close friends. The Gascon campaign cost more than £200,000. It used up all the money meant for Henry's crusade. This left him deeply in debt. He had to rely on loans from his brother Richard and the Lusignans.

The Sicilian Plan

Henry didn't give up on his hopes for a crusade. But he became more and more focused on trying to get the rich Kingdom of Sicily for his son Edmund. Sicily had been controlled by Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire. Frederick had been a rival of Pope Innocent IV for many years. When Frederick died in 1250, Innocent started looking for a new ruler. He wanted someone more friendly to the Pope. Henry saw Sicily as a valuable prize for his son. He also saw it as a great base for his crusade plans in the east. With very little discussion in his court, Henry agreed with the Pope in 1254 that Edmund should be the next king. Innocent urged Henry to send Edmund with an army to take Sicily from Frederick's son Manfred. He offered to help pay for the campaign.

Pope Innocent was followed by Pope Alexander IV. Alexander was facing growing military pressure from the Empire. He could no longer afford to pay Henry's expenses. Instead, he demanded that Henry pay the Pope back for the £90,000 already spent on the war. This was a huge amount of money. Henry asked parliament for help in 1255, but they refused. He tried again, but by 1257, parliament had only offered partial help.

Alexander became more and more unhappy with Henry's delays. In 1258, he sent a messenger to England. He threatened to excommunicate Henry if he didn't first pay his debts to the Pope. Then he had to send the promised army to Sicily. Parliament again refused to help the King raise this money. Instead, Henry forced money from senior church leaders. They were made to sign blank charters. These promised to pay almost unlimited amounts of money to support the King's efforts. This raised about £40,000. The English Church felt the money was wasted. It disappeared into the long war in Italy.

Meanwhile, Henry tried to influence the elections in the Holy Roman Empire. These would choose a new King of the Romans. When the more famous German candidates didn't gain support, Henry started backing his brother Richard. He gave money to Richard's potential supporters in the Empire. Richard was elected in 1256. People expected him to possibly be crowned the Holy Roman Emperor. But he continued to play a major role in English politics. His election received mixed reactions in England. Richard was believed to give moderate, sensible advice. English nobles missed his presence. But he also faced criticism, probably unfairly, for funding his German campaign at England's expense. Although Henry now had more support in the Empire for a possible alliance against Louis of France, the two kings were now moving towards settling their disputes peacefully. For Henry, a peace treaty could let him focus on Sicily and his crusade.

Henry's Later Reign (1258–1272)

The Barons' Revolt

In 1258, Henry faced a revolt from the English nobles. Anger had grown about how the King's officials were raising money. People also disliked the influence of the Poitevins at court and his unpopular plan for Sicily. They also resented the misuse of purchased Jewish loans. Even the English Church had complaints about how the King treated it. The Welsh were still openly rebelling. Now they had allied with Scotland.

Henry was also very short on money. He still had some gold and silver, but it wasn't enough. It couldn't cover his potential spending, including the campaign for Sicily and his debts to the Pope. Critics darkly suggested he never really meant to join the crusades. They thought he just wanted to profit from the crusade taxes. To make things worse, England's harvests failed. Within Henry's court, there was a strong feeling that the King couldn't lead the country through these problems.

The unhappiness finally exploded in April. Seven major English and Savoyard nobles secretly formed an alliance. They were Simon de Montfort, Roger and Hugh Bigod, John Fitzgeoffrey, Peter de Montfort, Peter de Savoy, and Richard de Clare. The Queen probably quietly supported their plan to expel the Lusignans from court. On April 30, Roger Bigod marched into Westminster during the King's parliament. He was backed by his co-conspirators. They carried out a coup d'état (a sudden takeover of power). Henry, fearing he would be arrested, agreed to stop ruling personally. Instead, he would govern through a council of 24 nobles and churchmen. Half would be chosen by the King, and half by the nobles. His own choices for the council relied heavily on the hated Lusignans.

Pressure for reform continued to grow. A new parliament met in June. It passed a set of rules called the Provisions of Oxford. Henry swore to uphold them. These provisions created a smaller council of 15 members. Only the nobles elected them. This council then had the power to appoint England's chief justice, chancellor, and treasurer. It would be monitored by parliaments held three times a year. Pressure from the lesser nobles and gentry at Oxford also helped pass wider reforms. These aimed to limit the abuse of power by both Henry's officials and the major nobles. The elected council included representatives of the Savoyard group but no Poitevins. The new government immediately exiled the main Lusignans. They also seized key castles across the country.

Disagreements among the leading nobles involved in the revolt soon became clear. Simon pushed for radical reforms. These would further limit the power of both the major nobles and the King. Others, like Hugh Bigod, wanted only moderate changes. Conservative nobles, like Richard, worried about the existing limits on the King's powers. Henry's son, Edward, at first opposed the revolution. But then he allied with de Montfort. He helped him pass the radical Provisions of Westminster in 1259. These introduced more limits on the major nobles and local royal officials.

A Time of Crisis

Over the next four years, neither Henry nor the nobles could bring stability to England. Power shifted back and forth between different groups. One of the new government's priorities was to settle the long-standing dispute with France. In late 1259, Henry and Eleanor left for Paris. They went to negotiate the final details of a peace treaty with King Louis. Simon de Montfort and many of the noble government escorted them. Under the treaty, Henry gave up any claim to his family's lands in northern France. But he was confirmed as the rightful ruler of Gascony and other nearby territories in the south. He paid homage and recognized Louis as his feudal lord for these lands.

When Simon de Montfort returned to England, Henry, supported by Eleanor, stayed in Paris. He used the opportunity to regain royal authority. He began issuing royal orders independently of the nobles. Henry finally returned to take back power in England in April 1260. Conflict was brewing between Richard de Clare's forces and those of Simon and Edward. Henry's brother Richard helped mediate between the groups. He prevented a military fight. Edward made peace with his father. Simon was put on trial for his actions against the King. Henry couldn't keep his grip on power. In October, a group led by Simon, Richard, and Edward briefly took back control. Within months, their noble council also fell into chaos.

Henry continued to publicly support the Provisions of Oxford. But he secretly started talks with Pope Urban IV. He hoped to be freed from the oath he had made at Oxford. In June 1261, the King announced that Rome had released him from his promises. He quickly staged a counter-coup with Edward's support. He removed his enemies from sheriff positions. He seized back control of many royal castles. The noble opposition, led by Simon and Richard, temporarily united against Henry's actions. They held their own parliament, separate from the King. They set up a rival system of local government across England. Henry and Eleanor gathered their supporters and raised a foreign mercenary army. Facing the threat of open civil war, the nobles backed down. De Clare switched sides again. Simon went into exile in France. The noble resistance collapsed.

Henry's government relied mainly on Eleanor and her Savoyard supporters. It didn't last long. He tried to solve the crisis permanently. He forced the nobles to agree to the Treaty of Kingston. This treaty set up a system to settle disputes between the King and the nobles. Richard would be the first judge. If he failed, Louis of France would step in. Henry softened some of his policies because of the nobles' concerns. But he soon started targeting his political enemies. He also restarted his unpopular Sicilian policy. He had done nothing significant to address concerns about nobles and the King misusing Jewish debts.

Henry's government was weakened by Richard's death. His heir, Gilbert de Clare, 5th Earl of Gloucester, sided with the radicals. The King's position was further hurt by major Welsh attacks along the Marches. The Pope also reversed his judgment on the Provisions, this time confirming them as legitimate. By early 1263, Henry's authority had fallen apart. The country slid back towards open civil war.

The Second Barons' War

Simon returned to England in April 1263. He called a meeting of rebel nobles in Oxford. They wanted to push for new rules against the Poitevins. A revolt broke out shortly after in the Welsh Marches. By October, England faced a likely civil war. It was between Henry, backed by Edward, Hugh Bigod, and the conservative nobles, and Simon, Gilbert de Clare, and the radicals. The rebels used concerns among knights about misused Jewish loans. Knights feared losing their lands. This was a problem Henry had largely created and done nothing to solve. In each case, the rebels used violence and killings. They deliberately tried to destroy records of their debts to Jewish lenders.

Simon marched east with an army. London rose up in revolt, and 500 Jewish people died there. Henry and Eleanor were trapped in the Tower of London by the rebels. The Queen tried to escape up the River Thames to join Edward's army at Windsor. But the London crowds forced her to turn back. Simon took Henry and Eleanor prisoner. Although he pretended to rule in Henry's name, the rebels completely replaced the royal government and household with their own trusted men.

Simon's group quickly began to break apart. Henry regained his freedom to move around. New chaos spread across England. Henry asked Louis of France to settle the dispute, as agreed in the Treaty of Kingston. Simon was at first against this idea. But as war became more likely, he also agreed to French arbitration. Henry went to Paris in person, with Simon's representatives. At first, Simon's legal arguments were strong. But in January 1264, Louis announced the Mise of Amiens. He condemned the rebels, upheld the King's rights, and canceled the Provisions of Oxford. Louis had strong beliefs about kings' rights over nobles. But he was also influenced by his wife, Margaret, who was Eleanor's sister, and by the Pope. Leaving Eleanor in Paris to gather more soldiers, Henry returned to England in February 1264. Violence was brewing in response to the unpopular French decision.

The Second Barons' War finally began in April 1264. Henry led an army into Simon's lands in the Midlands. Then he moved south-east to retake the important route to France. Becoming desperate, Simon marched after Henry. The two armies met at the Battle of Lewes on May 14. Despite having more soldiers, Henry's forces were defeated. His brother Richard was captured. Henry and Edward retreated to a local church and surrendered the next day. Henry was forced to pardon the rebel nobles and bring back the Provisions of Oxford. This left him, as historian Adrian Jobson describes, "little more than a figurehead." With Henry's power reduced, Simon canceled many debts and interest owed to Jewish people. This included those held by his noble supporters.

Simon couldn't make his victory last. Widespread disorder continued across the country. In France, Eleanor planned an invasion of England with Louis's support. Edward escaped his captors in May and formed a new army. He chased Simon's forces through the Marches. Then he struck east to attack Simon's fortress at Kenilworth. After that, he turned once more on the rebel leader himself. Simon, with the captive Henry, couldn't retreat. The Battle of Evesham followed.

Edward won, and Simon was killed. Henry, who was wearing borrowed armor, was almost killed by Edward's forces. But they recognized the King and took him to safety. In some places, the rebellion, now without a leader, continued. Some rebels gathered at Kenilworth Castle. Henry and Edward took it after a long siege in 1266. They continued to target Jewish people and their debt records. The remaining pockets of resistance were cleared. The last rebels, hiding in the Isle of Ely, surrendered in July 1267. This marked the end of the war.

Peace and Rebuilding

Henry quickly took revenge on his enemies after the Battle of Evesham. He immediately ordered the seizure of all rebel lands. This caused a wave of chaotic looting across the country. Henry at first rejected any calls for moderation. But in October 1266, Papal Legate Ottobuono de' Fieschi convinced him to issue a less harsh policy. This was called the Dictum of Kenilworth. It allowed rebels to get their lands back if they paid heavy fines. The Statute of Marlborough followed in November 1267. This effectively reissued much of the Provisions of Westminster. It placed limits on the powers of local royal officials and major nobles. But it did not restrict the King's central authority. Most of the exiled Poitevins began to return to England after the war. In September 1267, Henry made the Treaty of Montgomery with Llywelyn. He recognized Llywelyn as the Prince of Wales and gave him significant land.

In the last years of his reign, Henry became increasingly weak. He focused on securing peace in the kingdom and his religious duties. Edward became the Steward of England. He began to play a more important role in government. Henry's finances were in a bad state because of the war. When Edward decided to join the crusades in 1268, it became clear that new taxes were needed. Henry was worried that Edward's absence might encourage more revolts. But his son convinced him to negotiate with several parliaments over the next two years to raise the money.

Henry had at first reversed Simon de Montfort's anti-Jewish policies. He tried to restore debts owed to Jewish people where they could be proven. But he faced pressure from parliament to introduce restrictions on Jewish bonds. This included their sale to Christians. This happened in the final years of his reign in return for funding. Henry continued to invest in Westminster Abbey. It became a replacement for the family tomb at Fontevraud Abbey. In 1269, he oversaw a grand ceremony to rebury Edward the Confessor in a lavish new shrine. He personally helped carry the body to its new resting place.

Henry's Death

Edward left for the Eighth Crusade, led by Louis of France, in 1270. But Henry became increasingly ill. Concerns about a new rebellion grew. The next year, the King wrote to his son asking him to return to England. But Edward did not turn back. Henry recovered slightly. He announced his renewed intention to join the crusades himself. But he never fully regained his health. On the evening of November 16, 1272, he died in Westminster. Eleanor was probably with him. Edward succeeded him. He slowly made his way back to England through Gascony. He finally arrived in August 1274.

At his request, Henry was buried in Westminster Abbey. He was placed in front of the church's high altar. This was the former resting place of Edward the Confessor. A few years later, work began on a grander tomb for Henry. In 1290, Edward moved his father's body to its current location in Westminster Abbey. His gilt-brass tomb effigy was designed and made within the abbey grounds by William Torell. Unlike other statues of the period, it is very realistic. But it is probably not an exact likeness of Henry himself.

Eleanor probably hoped Henry would be recognized as a saint. Her contemporary, Louis IX of France, had been. Indeed, Henry's final tomb looked like a saint's shrine. It had niches possibly meant to hold holy objects. When the King's body was removed in 1290, people at the time noted that the body was in perfect condition. Henry's long beard was still well preserved. At the time, this was seen as a sign of saintly purity. Miracles began to be reported at the tomb. But Edward was doubtful about these stories. The reports stopped, and Henry was never made a saint. In 1292, his heart was removed from his tomb. It was reburied at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou, France. It was placed with the bodies of his Angevin family.

Henry III's Legacy

How Historians See Henry III

The first histories about Henry's reign appeared in the 1500s and 1600s. They mostly used accounts from medieval writers, especially Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris. These early historians, like Archbishop Matthew Parker, were influenced by ideas of their own time. They looked at the changing roles of the Church and state under Henry. They also examined the rise of English nationalism and what they saw as the bad influence of the Pope. During the English Civil War, historians also compared Henry's experiences to those of the deposed Charles I.

By the 1800s, Victorian scholars like William Stubbs, James Ramsay, and William Hunt wanted to understand how the English political system developed under Henry. They explored the rise of Parliament during his reign. They also agreed with the medieval writers' concerns about the Poitevins in England. This focus continued into early 1900s research on Henry. For example, Kate Norgate's 1913 book still heavily used the old accounts. It focused mainly on government issues, with a strong nationalistic bias.

After 1900, financial and official records from Henry's reign became available to historians. These included financial records, court documents, letters, and records of royal forests. Thomas Frederick Tout used these new sources a lot in the 1920s. Historians after World War II focused on Henry's government finances. They highlighted his money problems. This wave of research led to Sir Maurice Powicke's two major books about Henry. They were published in 1948 and 1953. These books became the accepted history of the King for the next thirty years.

Henry's reign didn't get much attention from historians for many years after the 1950s. No major biographies of Henry were written after Powicke's. Historian John Beeler noted in the 1970s that military historians had written very little about Henry's reign. In the late 1900s, there was new interest in 13th-century English history. This led to many specialized books on parts of Henry's reign. These included government finances and his younger years. Current historians note both Henry's good and bad qualities. Historian David Carpenter judges him to have been a decent man. But he failed as a ruler because he was naive and couldn't make realistic plans. Huw Ridgeway agrees, noting his lack of worldly experience and inability to manage his court. But Ridgeway also considers him to have been "essentially a man of peace, kind and merciful."

Henry III in Popular Culture

The writer Matthew Paris drew pictures of Henry's life. He sketched and sometimes colored these in the margins of his book, the Chronica Majora. Paris first met Henry in 1236. He had a long relationship with the King. However, he disliked many of Henry's actions, and his drawings are often not very flattering.

Henry is a character in Purgatorio, the second part of Dante's Divine Comedy (finished in 1320). The King is shown sitting alone in purgatory. He is to one side of other failed rulers: Rudolf I of Germany, Ottokar II of Bohemia, Philip III of France, and Henry I of Navarre. Also there are Charles I of Naples and Peter III of Aragon. It's not clear why Dante showed Henry sitting separately. Possible reasons include that England was not part of the Holy Roman Empire. Or it might mean Dante had a good opinion of Henry because of his unusual religious devotion. His son, Edward, is also praised by Dante in this work (Canto VII. 132).

Henry appears in King John by William Shakespeare. He is a small character called Prince Henry. But in modern popular culture, Henry has a very small presence. He has not been a main subject of films, plays, or television shows. Historical novels that feature him include Longsword, Earl of Salisbury: An Historical Romance (1762) by Thomas Leland, The Red Saint (1909) by Warwick Deeping, The Outlaw of Torn (1927) by Edgar Rice Burroughs, The De Montfort Legacy (1973) by Pamela Bennetts, The Queen from Provence (1979) by Jean Plaidy, The Marriage of Meggotta (1979) by Edith Pargeter, and Falls the Shadow (1988) by Sharon Kay Penman.

Henry III's Children

Henry and Eleanor had five children:

- Edward I (born June 17/18, 1239 – died July 7, 1307)

- Margaret (born September 29, 1240 – died February 26, 1275)

- Beatrice (born June 25, 1242 – died March 24, 1275)

- Edmund (born January 16, 1245 – died June 5, 1296)

- Katherine (born November 25, 1253 – died May 3, 1257)

Henry had no known children born outside of marriage.

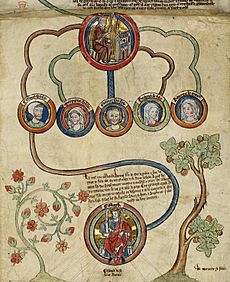

Family Tree

| Henry III and his family | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See Also

In Spanish: Enrique III de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Enrique III de Inglaterra para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |