History of Dublin facts for kids

The city of Dublin has a history stretching back over 1,000 years. For most of this time, it has been Ireland's most important city and the main center for culture, education, and industry on the island.

Contents

Dublin's Early Days: Vikings and Normans

Some people think Dublin was first mentioned by a Greek mapmaker named Ptolemy around 140 AD. He wrote about a place called Eblana. This would mean Dublin is almost 2,000 years old! However, experts now think Eblana was probably not Dublin.

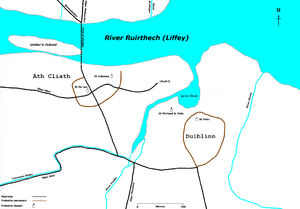

In the 800s and 900s, there were two settlements where Dublin is today. The Vikings arrived around 841 and called their settlement Dyflin. This name came from the Irish words Duiblinn, meaning "black pool." This "black pool" was a dark tidal area where the River Poddle flowed into the River Liffey, near where Dublin Castle is now.

The other settlement was a Gaelic one, called Áth Cliath, which means "ford of hurdles." This was further up the river. Today, "Áth Cliath" is still the Irish name for Dublin.

The Vikings, also known as Ostmen, ruled Dublin for almost 300 years. They were kicked out in 902 but came back in 917. Even after the Irish High King Brian Boru defeated them at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, they stayed in Dublin, focusing more on trade.

Viking rule in Dublin ended completely in 1171. This happened when King Dermot MacMurrough of Leinster captured the city with help from Norman soldiers. The last Viking King of Dublin, Ascall mac Ragnaill, tried to get the city back, but he failed and was killed.

The Thingmote was a large mound, about 12 meters high and 73 meters around. This is where the Norsemen (Vikings) met to make their laws. It was near Dublin Castle until 1685. Viking Dublin also had a big slave market. People were captured and sold as slaves by both the Vikings and Irish chiefs.

Dublin celebrated its 1,000th birthday in 1988 with the slogan "Dublin's Great in '88." The city is actually much older, but this celebration marked the year (989, not 988) when the Norse King Glun Iarainn agreed to pay taxes to the Irish High King Máel Sechnaill II.

After the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169–71, Dublin became the center of English power in Ireland. It replaced Tara as the most important political place. On May 15, 1192, Dublin received its first written Charter of Liberties from John, who was then Lord of Ireland. This document gave certain rights to the people living there. In 1229, his son Henry allowed citizens to elect a mayor.

By 1400, many of the Norman conquerors had started to adopt Irish language and customs. This left only a small area around Dublin, called the Pale, under direct English control.

Life in Medieval Dublin

After the Anglo-Normans took Dublin in 1171, many of the city's Viking residents moved to the north side of the River Liffey and built their own settlement called Ostmantown (or "Oxmantown"). County Dublin was the first county in Ireland to be officially set up in the 1190s, and Dublin became the capital of the English Lordship of Ireland. Many settlers from England and Wales moved to Dublin and the areas around it. In the 1300s, this area was protected against the Irish and became known as The Pale.

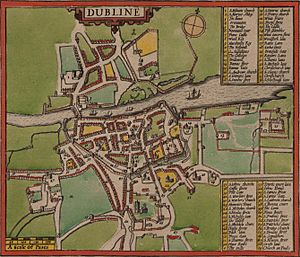

English rule in Dublin was based at Dublin Castle. The city was also the main place where the Parliament of Ireland met from 1297. Important buildings from this time include St Patrick's Cathedral, Christchurch Cathedral, and St. Audoen's Church.

People living in the Pale felt like they were in a small, safe area surrounded by "wild natives." A good example of this feeling was their yearly trip to a place called Cullenswood in Ranelagh. In 1209, 500 new settlers from Bristol were killed there by the O'Toole clan during an outing. Every year on "Black Monday," Dublin citizens would march to this spot. They would raise a black flag towards the mountains to challenge the Irish to battle. This was so dangerous that until the 1600s, the city's army had to guard them.

Medieval Dublin was a small, close-knit city with about 5,000 to 10,000 people. It was small in area, only about three square kilometers on the south side of the Liffey. Outside the city walls were areas like the Liberties and Irishtown. Irish people were supposed to live in Irishtown, as a 15th-century law had forced them out of the main city. However, many Irish people still lived in Dublin, and by the 1500s, English reports complained that Irish Gaelic was becoming as common as English in the Pale.

Life in Medieval Dublin was often difficult. In 1348, the city was hit by the Black Death, a deadly disease that spread across Europe. In Dublin, victims were buried in mass graves in an area still called "Blackpitts." However, recent discoveries suggest the name might also come from tanning pits that stained the area dark. The plague returned often until its last major outbreak in 1649.

Throughout the Middle Ages, Dublin paid "black rent" or protection money to nearby Irish clans to avoid their attacks. In 1315, a Scottish army led by Edward the Bruce burned the city's suburbs. As England became less interested in its Irish colony, the defense of Dublin was left to the Fitzgerald Earls of Kildare. This powerful family often followed their own plans. In 1487, they occupied Dublin and declared Lambert Simnel to be King of England. In 1537, another Fitzgerald, Silken Thomas, attacked Dublin Castle. Henry VIII then sent a large army to defeat the Fitzgeralds and put English officials in charge. This marked the start of a much closer, though sometimes difficult, relationship between Dublin and the English Crown.

Changes in the 1500s and 1600s

Dublin and its people changed a lot during the 1500s and 1600s. This was when England, under the Tudor dynasty, fully conquered the whole island of Ireland. The "Old English" community in Dublin, who were mostly Roman Catholics, were happy about the conquest of the native Irish. However, they were upset by the Protestant reformation in England. They also disliked being forced to pay for English soldiers through a tax called "cess." Some Dubliners were even executed for supporting a rebellion in the 1580s. The Mayoress of Dublin, Margaret Ball, died in prison in Dublin Castle in 1584 because of her Catholic beliefs.

In 1592, Queen Elizabeth I opened Trinity College Dublin as a Protestant university for Irish wealthy families. But important Dublin families often sent their sons to Catholic universities in Europe instead.

The people of Dublin were also unhappy during the Nine Years War in the 1590s. English soldiers were made to stay in Dubliners' homes, which spread disease and made food prices go up. Wounded soldiers lay in the streets because there was no proper hospital. To make things worse, in 1597, the English Army's gunpowder storage in Winetavern Street exploded by accident, killing almost 200 Dubliners. Even with these problems, the Old English community in Dublin remained against the Gaelic Irish leader, Hugh O'Neill.

Because of these tensions, English leaders started to see Dubliners as untrustworthy. They encouraged Protestants from England to settle there. These "New English" became the main group running Ireland until the 1800s.

Protestants became the majority in Dublin in the 1640s. Thousands of them fled to the city to escape the Irish Rebellion of 1641. When Irish Catholic forces later threatened Dublin, its English army forced Catholic Dubliners out of the city. In the 1640s, the city was attacked twice during the Irish Confederate Wars, in 1646 and 1649. But each time, the attackers were pushed back.

In 1649, during the second attack, a combined force of Irish Catholics and English Royalists was defeated by Dublin's English Parliamentarian army in the Battle of Rathmines, just outside the city.

In the 1650s, after the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Catholics were officially banned from living in Dublin under the harsh Cromwellian settlement. However, this law was not always strictly enforced. Eventually, this religious unfairness caused the Old English community to stop seeing themselves as English and instead feel they were part of the native Irish community.

By the end of the 1600s, Dublin was the capital of the English-controlled Kingdom of Ireland. It was ruled by the Protestant "New English" minority. In 1700, Dublin (and parts of Ulster) was the only place in Ireland where Protestants were the majority. In the next century, Dublin grew much larger, more peaceful, and more successful than ever before.

Dublin in the 1700s and 1800s

From Medieval to Georgian City

By the early 1700s, the English had firm control and had put in place harsh "Penal Laws" against the Catholic majority in Ireland. However, in Dublin, the Protestant Ascendancy (the ruling Protestant class) was doing very well, and the city grew quickly. By 1700, Dublin's population was over 60,000, making it the second-largest city in the British Empire after London.

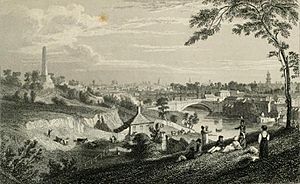

In the 1700s, many of Dublin's famous Georgian buildings and street designs were built. At the start of the century, Dublin was a medieval city with narrow streets. But during the 1700s, it was largely rebuilt. The Wide Streets Commission knocked down many old, narrow streets and replaced them with wide, grand Georgian streets. Famous streets like Sackville Street (now O'Connell Street), Dame Street, Westmoreland Street, and D'Olier Street were created this way.

Five large Georgian squares were also built: Rutland Square (now Parnell Square) and Mountjoy Square on the north side, and Merrion Square, Fitzwilliam Square, and Saint Stephen's Green on the south side of the River Liffey. At first, the richest people lived on the north side. But when the Earl of Kildare (Ireland's most important noble) built his new house, Kildare House (now Leinster House), on the south side, many other nobles quickly built their homes around the southern squares.

In 1745, Jonathan Swift, a famous writer and Dean of St. Patrick's, left his money to start a hospital for people with mental health issues. St Patrick's Hospital was granted a Royal Charter in 1746. It was designed to meet the needs of patients and is one of the oldest psychiatric hospitals in the world.

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1510 | 6,443 | — |

| 1550 | 6,771 | +5.1% |

| 1580 | 7,003 | +3.4% |

| 1585 | 5,833 | −16.7% |

| 1600 | 7,532 | +29.1% |

| 1610 | 6,266 | −16.8% |

| 1613 | 6,020 | −3.9% |

| 1616 | 5,913 | −1.8% |

| 1621 | 5,888 | −0.4% |

| 1631 | 5,714 | −3.0% |

| 1641 | 5,888 | +3.0% |

| 1651 | 6,024 | +2.3% |

| 1653 | 6,133 | +1.8% |

| 1659 | 8,780 | +43.2% |

| 1695 | 47,000 | +435.3% |

| 1715 | 89,000 | +89.4% |

| 1733 | 123,000 | +38.2% |

| 1760 | 141,000 | +14.6% |

| 1778 | 154,000 | +9.2% |

| 1798 | 180,000 | +16.9% |

| 1813 | 176,610 | −1.9% |

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1821 | 186,276 | — |

| 1831 | 232,362 | +24.7% |

| 1841 | 233,726 | +0.6% |

| 1851 | 254,810 | +9.0% |

| 1861 | 263,751 | +3.5% |

| 1871 | 267,717 | +1.5% |

| 1881 | 349,583 | +30.6% |

| 1891 | 352,541 | +0.8% |

| 1901 | 290,638 | −17.6% |

| 1911 | 304,802 | +4.9% |

| 1926 | 404,094 | +32.6% |

| 1936 | 472,912 | +17.0% |

| 1946 | 506,051 | +7.0% |

| 1951 | 580,388 | +14.7% |

| 1956 | 584,483 | +0.7% |

| 1961 | 537,448 | −8.0% |

| 1966 | 588,773 | +9.5% |

| 1971 | 567,866 | −3.6% |

| 1979 | 544,586 | −4.1% |

| 1981 | 525,882 | −3.4% |

| 1986 | 502,749 | −4.4% |

| 1991 | 478,389 | −4.8% |

| 1996 | 481,854 | +0.7% |

| 2002 | 495,101 | +2.7% |

| 2006 | 506,211 | +2.2% |

| 2011 | 525,383 | +3.8% |

| 2016 | 553,165 | +5.3% |

| 2022 | 588,233 | +6.3% |

Even with its grand architecture and music (like Handel's "Messiah" first performed there), 18th-century Dublin still had rough parts. Its poor population grew quickly as people moved from the countryside, living mostly in the north and southwest of the city. Rival gangs, like the "Liberty Boys" (Protestant weavers) and the "Ormonde Boys" (Catholic butchers), fought violent street battles. It was also common for Dublin crowds to protest violently outside the Parliament of Ireland when unpopular laws were passed.

As more people moved from rural areas to Dublin, the city's population balance changed again. Catholics became the majority in the city by the late 1700s.

Rebellion and Union with Britain

Until 1800, Dublin was home to the Parliament of Ireland. This parliament was independent, but only rich Protestant landowners could be members. By the late 1700s, these Irish Protestants, many of whom were descendants of British settlers, began to see Ireland as their own country. This "Patriot Parliament" successfully pushed for more self-rule and better trade with Britain. From 1778, the Penal Laws, which treated Roman Catholics unfairly, were slowly removed.

However, inspired by the American and French revolutions, some Irish radicals formed the United Irishmen. They wanted to create an independent, fair, and democratic Irish republic. Leaders like Napper Tandy and Edward Fitzgerald were from Dublin. The United Irishmen planned a rebellion in Dublin in 1798, but their leaders were arrested, and the city was taken over by British soldiers before the rebels could gather. There was some fighting on the edges of the city, but Dublin itself remained under British control during the 1798 rebellion.

The Protestant leaders and the British government were shocked by the events of the 1790s. Because of this, in 1801, the Irish Parliament voted itself out of existence under the Irish Act of Union. This joined the Kingdom of Ireland with the Kingdom of Great Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Dublin lost its status as a capital city.

Although Dublin continued to grow, it suffered financially. Many wealthy people, including nobles and politicians, no longer came to the city for parliamentary sessions. This meant less money was spent in Dublin. Many of the city's once grand Georgian houses quickly became slums. In 1803, Robert Emmet launched another short rebellion in the city, but it was easily put down, and Emmet was executed.

In 1829, wealthier Irish Catholics regained full citizenship rights in the United Kingdom. This was partly thanks to Daniel O'Connell, who organized large meetings in Dublin and other places to push for "Catholic Emancipation" (equal rights for Catholics).

In 1840, a new law called the Corporation Act changed local government in Ireland. In Dublin, this meant that the old system, which only allowed Protestant property owners to vote, was abolished. Now, all property owners who paid over ten pounds a year could vote for Dublin Corporation. This meant Catholics, who had been excluded since the 1690s, became the majority of voters. As a result, Daniel O'Connell was elected mayor in 1841, the first Catholic mayor in 150 years.

O'Connell also campaigned for Ireland to have its own parliament again, a movement called "Repeal of the Union." He organized huge rallies, called "Monster Meetings," to pressure the British government. The biggest meeting was planned for Clontarf, just north of Dublin, a place important because of the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. Hundreds of thousands of people were expected, but the British government banned the meeting and sent in troops. O'Connell backed down, and his movement lost its momentum.

Late 1800s Dublin

After Catholics gained more rights and voting rules changed, Irish nationalists (mostly Catholics) took control of Dublin's local government after 1840. Daniel O'Connell became the first Catholic Mayor in 150 years. As people became wealthier, many of Dublin's Protestant and Unionist middle-class families moved out of the city center to new suburbs like Ballsbridge, Rathmines, and Rathgar. These areas are still known for their beautiful Victorian architecture. A new railway also connected Dublin to the middle-class suburb of Dún Laoghaire, which was renamed Kingstown in 1821.

Unlike Belfast in the north, Dublin did not experience the full effects of the Industrial Revolution. Because of this, there were always many unemployed people in the city. Industries like the Guinness brewery, Jameson Distillery, and Jacob's biscuit factory provided the most stable jobs. New working-class suburbs grew up around these factories in places like Kilmainham and Inchicore. Another big employer was the Dublin tramways system. By 1900, Belfast had a larger population than Dublin, though Dublin is larger today.

In 1867, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, also known as the 'Fenians', tried to start a rebellion to end British rule in Ireland. However, the rebellion was poorly organized and did not succeed. In Dublin, the fighting was mostly in the suburb of Tallaght. Several thousand Fenians marched to Tallaght Hill, and some fought a brief battle with the police. But because of poor leadership, they soon scattered, and many were arrested. This rebellion failed, but it did not stop nationalist violence.

Under the Local Government Act of 1898, more people could vote for Dublin Corporation. Local government also gained more powers. This was part of a British plan to calm Irish nationalist feelings.

Dublin in the Early 1900s

The Lockout of 1913

In 1913, Dublin saw one of the biggest and toughest labor disputes in Britain or Ireland, known as the Lockout. James Larkin, a strong trade union leader, started the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU). He tried to get better pay and conditions for workers who didn't have special skills. He used talks and, if needed, strikes.

In response, William Martin Murphy, who owned the Dublin Tram Company, organized a group of employers. They agreed to fire any ITGWU members and make other workers promise not to join the union. Larkin then called the tram workers out on strike. This led to other workers in Dublin being fired, or "locked out," if they wouldn't leave the union. Within a month, 25,000 workers were either on strike or locked out.

During the dispute, there were violent riots with the Dublin Metropolitan Police. Three people died, and hundreds were hurt. In response, James Connolly formed the Irish Citizen Army to protect the striking workers from the police. The lockout lasted for six months. In the end, most workers, many of whose families were starving, left the union and went back to work.

End of British Rule in Dublin

In 1914, after almost 30 years of campaigning, Ireland seemed close to getting "Home Rule" (self-government). However, instead of a peaceful change, Dublin and Ireland faced almost ten years of violence and instability. This eventually led to a much bigger break from Britain than Home Rule would have been. By 1923, Dublin was the capital of the Irish Free State, an almost independent Irish state that governed 26 of Ireland's 32 counties.

Howth Gun Running in 1914

Unionists, mainly in Ulster but also in Dublin, did not want Home Rule. They formed their own private army, the Ulster Volunteers (UVF). In response, nationalists formed the Irish Volunteers to make sure Home Rule happened. In April 1914, thousands of German weapons were brought into the north by the UVF. Some Irish Volunteers tried to do the same in July. The crew of the Asgard successfully landed German rifles and ammunition at Howth, near Dublin.

Soon after, British soldiers tried to take the weapons but failed. Dublin crowds booed the soldiers when they returned to the city center. The soldiers reacted by firing into the crowd at Bachelors Walk, killing three people. Ireland seemed on the edge of civil war when the Home Rule Bill was finally passed in September 1914. However, the start of World War I put the plan on hold.

John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, asked nationalists to join the British Army. This caused a split in the Volunteers. Thousands of Irishmen joined (especially from working-class areas with high unemployment), and many died in the war. The majority, who followed Redmond, formed the National Volunteers. A smaller, more militant group kept the name Irish Volunteers. Some of these were now ready to fight against British forces for Irish independence.

Easter Rising of 1916

In April 1916, about 1,250 armed Irish republicans led by Padraig Pearse started what became known as the Easter Rising in Dublin. They wanted an Irish Republic, not just Home Rule. One of their first actions was to declare this Republic. The rebels were made up of Irish Volunteers and the smaller Irish Citizen Army led by James Connolly.

The rebels took over strong points in the city, including the Four Courts, Stephen's Green, Boland's mill, and the General Post Office building on O'Connell Street, which became their headquarters. They held out for a week until British troops forced them to surrender. The British used artillery to bombard the rebels, sailing a gunboat up the Liffey and placing field guns around the city.

Much of the city center was destroyed by shelling. Around 450 people, about half of them civilians, were killed, and another 1,500 were injured. Fierce fighting happened along the Grand Canal at Mount Street, where British troops faced heavy losses. The rebellion also saw a lot of looting by Dublin's poor population, and many city center shops were robbed. The rebel commander, Patrick Pearse, surrendered after a week to prevent more civilian deaths.

At first, the rebellion was not popular in Dublin because of the death and destruction it caused. Many Dubliners also had relatives serving in the British Army. However, public opinion slowly but surely turned to support the rebels after 16 of their leaders were executed by the British military after the Rising. In December 1918, the party now taken over by the rebels, Sinn Féin, won most of the Irish parliamentary seats. Instead of going to the British House of Commons, they met in the Lord Mayor of Dublin's residence and declared the Irish Republic to be in existence, calling themselves Dáil Éireann (the Assembly of Ireland) – its parliament.

War of Independence (1919–1921)

Between 1919 and 1921, Ireland experienced the Irish War of Independence. This was a guerrilla war between British forces and the Irish Volunteers, now called the Irish Republican Army. The Dublin IRA units fought a city-based guerrilla campaign against the police and British army. In 1919, the violence began with a small group of IRA men, known as "the Squad," led by Michael Collins, assassinating police detectives in the city.

By late 1920, these operations became more intense, with regular gun and grenade attacks on British troops. The IRA in Dublin tried to carry out three attacks a day. Attacks on British patrols were so common that the Camden-Aungier streets area was nicknamed the "Dardanelles" by British soldiers.

The conflict led to many sad events in Dublin. The bloodiest day was Bloody Sunday on November 21, 1920. In the early morning, Michael Collins' "Squad" assassinated 18 British agents around the city. In revenge, British forces opened fire on a Gaelic football crowd in Croke Park that afternoon, killing 14 civilians and wounding 65. That evening, three republican activists were arrested and killed in Dublin Castle.

To stop the violence, British troops carried out major operations in Dublin to find IRA members. From January 15 to 17, 1921, they blocked off an area of the north inner city, searching houses for weapons and suspects. They did this again in February in other areas. However, these searches found few results.

The largest IRA operation in Dublin during the conflict happened on May 25, 1921. The IRA Dublin Brigade burned down The Custom House, one of Dublin's most beautiful buildings, which was the headquarters of local government. However, the British were quickly alerted and surrounded the building. Five IRA men were killed, and over 80 were captured. This was a good publicity move for the IRA but a military disaster.

Civil War (1922–23)

After a truce was declared on July 11, 1921, a peace agreement called the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed between Britain and Ireland. This created a self-governing Irish state of 26 counties, known as the Irish Free State. However, it also ended the Irish Republic, which many in the nationalist movement and the IRA felt they were sworn to protect. This led to the Irish Civil War of 1922–23, where republicans who opposed the treaty fought against those who accepted the compromise with the British.

The Civil War began in Dublin. Anti-Treaty forces led by Rory O'Connor took over the Four Courts and other buildings in April 1922. They hoped this would make the British restart the fighting. This put the Free State government, led by Michael Collins, in a difficult position: either face British military re-occupation or fight their own former comrades.

After some hesitation, and after Winston Churchill had ordered British troops to attack the rebels, Collins decided he had to act. He borrowed British artillery to shell the republicans in the Four Courts. They surrendered after a two-day bombardment (June 28–30, 1922). But some of their IRA comrades then occupied O'Connell Street, which saw street fighting for another week before the Free State Army secured the capital (see Battle of Dublin). Over 60 fighters were killed, including senior republican Cathal Brugha. About 250 civilians were also thought to have been killed or injured.

On December 6, 1922, the IRA assassinated Seán Hales, a member of the Dáil, as he left Leinster House in Dublin. This was in revenge for the Free State executing their prisoners. The next day, four republican leaders from the Four Courts (Rory O'Connor, Liam Mellows, Dick Barret, and Joe McKelvey) were executed in revenge. Dublin was relatively quiet after this, though guerrilla warfare continued in other parts of Ireland. The new Free State government eventually ended this rebellion by mid-1923. The civil war left a lasting bitterness in Irish politics.

Dublin in the 20th Century

Dublin suffered greatly between 1916 and 1922. It saw heavy street fighting during the 1916 Easter Rising and again at the start of the Civil War in 1922. Around 1,000 people died in Dublin during this period: 482 in the 1916 Rising, 309 in the 1919–21 War of Independence, and about 250 in the city and county during the 1922–23 Civil War.

Many of Dublin's beautiful buildings were destroyed. The historic General Post Office (GPO) was bombed in 1916. James Gandon's Custom House was burned by the IRA in the War of Independence. Another of Gandon's masterpieces, the Four Courts, was taken over by republicans and then bombed by the pro-treaty army. (Republicans also destroyed a thousand years of historical records there). These buildings were later rebuilt.

The new Irish Free State set itself up. Its Governor-General lived in the former Viceregal Lodge, because it was one of the few places safe from republican attackers. Parliament was temporarily set up in the Duke of Leinster's old palace, Leinster House, where it has been ever since. Over time, the GPO, Custom House, and Four Courts were rebuilt.

The "Emergency" (World War II)

Ireland was officially neutral during World War II. It was even called "The Emergency" in Ireland, not "the war." Although Dublin avoided the heavy bombing seen elsewhere, the German air force bombed Dublin on May 31, 1941. They hit the North Strand, a working-class area, killing 34 civilians and injuring 90. The bombing was said to be accidental.

During the war, rationing was put in place in Dublin. The small Jewish community temporarily grew as Jews fled Nazi persecution.

Tackling the Tenements

The first efforts to improve Dublin's large slum areas began in the late 1800s, but these only helped a few thousand families. The government's main focus in the early 1900s was building cottages for rural workers. Some city planning began in the first years of the Irish Free State and then really took off after 1932, when Éamon de Valera came to power. With more money and lower wages due to the Great Depression, big changes started. A plan to replace old tenements with good housing for Dublin's poor began. Some new suburbs like Marino and Crumlin were built, but Dublin's inner-city slums remained.

It wasn't until the 1960s that major progress was made in removing Dublin's tenements. Thousands of working-class Dubliners were moved to new suburban housing estates on the edge of the city. This project had mixed results. While the tenements were mostly gone, new housing was built so quickly that little planning went into it. New suburbs like Tallaght, Coolock, and Ballymun suddenly had huge populations, sometimes up to 50,000 people, without enough shops, public transport, or jobs. For decades, these places became known for crime and unemployment. In recent years, these problems have eased with Ireland's "Celtic Tiger" economic boom. Tallaght, especially, has become much more mixed and now has many shops, transport links, and leisure facilities. Ballymun Flats, one of the few high-rise housing projects, was largely torn down and rebuilt recently.

Ironically, with Ireland's new wealth and immigration, there is now a housing shortage in the city again. More jobs have led to a rapid rise in Dublin's population. As a result, housing prices have gone up sharply. This has caused many younger Dubliners to move to nearby counties like Meath, Louth, Kildare, and Wicklow, while still traveling to Dublin for work every day. This has created traffic problems and long commutes.

Georgian Dublin's Destruction in the 1960s

As part of the building program that cleared the inner-city slums, from the 1950s onwards, historic Georgian Dublin came under attack from the Irish Government's development plans. Large areas of 18th-century houses were torn down, especially in Fitzwilliam Street and St Stephen's Green, to make way for plain office blocks and government buildings. Much of this was driven by property developers who wanted to make money from the booming property market. Many buildings were approved by government ministers who had connections with the developers.

Some of this development was also encouraged by the strong nationalist ideas of that time. People wanted to remove physical reminders of Ireland's colonial past. An extreme example was the destruction of Nelson's Pillar on O'Connell Street in 1966. This statue of a famous British admiral had been a Dublin landmark for a century. It was blown up by a small bomb shortly before the 50-year anniversary of the Easter Rising. In 2003, the Pillar was replaced by the Dublin Spire on the same spot. This 120-meter-tall metal pole is the tallest structure in Dublin city center and can be seen for miles.

The destructive building practices of the 1960s continued and even got worse. Concrete office blocks were replaced with buildings that looked like old Georgian houses but were new. Large parts of Harcourt Street and St. Stephen's Green were torn down and rebuilt this way in the 1970s and 1980s, as were parts of Parnell Square and other areas. Many saw this as an "easy way out" for planners; an old-looking front was kept, while "progress" continued. This planning policy continued until around 1990, when efforts to preserve old buildings finally became stronger.

However, it wasn't just sites linked to the British presence that were destroyed. Wood Quay, where the oldest remains of Viking Dublin were found, was also torn down to build the headquarters of Dublin's local government. This happened despite a long and bitter fight between the government and people who wanted to preserve the site. More recently, there was a similar argument about building the M50 motorway through the site of Carrickmines Castle, an important medieval site. There have been claims that much controversial building work in Dublin was allowed because of bribery and favors between politicians and developers. Since the late 1990s, several investigations have been set up to look into corruption in Dublin's planning process.

The Northern Troubles

Dublin was affected in different ways by "the Troubles," a conflict in Northern Ireland from 1969 to the late 1990s. In 1972, angry crowds in Dublin burned down the British Embassy in Merrion Square. This was a protest against British troops shooting 13 civilians in Derry on Bloody Sunday (1972). The IRA Southern Command was based in Dublin and helped with training, recruiting, money, safe houses, and getting weapons to support IRA operations in Northern Ireland. This safe place in the Republic helped the conflict last longer.

However, the city generally did not experience direct paramilitary violence, except for a period in the early to mid-1970s when it was targeted by several loyalist bombings.

In 1981, there was strong support in Dublin for republican prisoners on hunger strike in Northern Ireland. Over 15,000 Anti H-Block Irish republican protesters tried to storm the new British Embassy (rebuilt after 1972). This led to several hours of violent rioting with over 1,500 Gardaí (Irish police), before the protesters were scattered. Over 200 people were injured, and dozens were arrested.

Other, more peaceful protests were held in Dublin in the 1990s, calling for an end to the Provisional IRA campaign in the North.

Dublin's Modern Makeover

Since the 1980s, Dublin's planners have become more aware of the need to protect the city's old buildings. Most of Dublin's Georgian neighborhoods now have protection orders. This new awareness was also seen in the development of Temple Bar. This was the last part of Dublin that still had its original medieval street plan. In the 1970s, the state transport company bought many buildings there to build a large bus station. However, artists had rented most of the buildings, creating a sudden "cultural quarter" that reminded people of Paris's Left Bank. The lively atmosphere of Temple Bar led to calls for its protection. By the late 1980s, the bus station plans were dropped, and a plan was put in place to keep Temple Bar as Dublin's cultural heart, with government support. This has had mixed results. The medieval street plan survived, but rents went up a lot, forcing artists to move. They were replaced by restaurants and bars that attract many tourists. Also, in the late 1980s, the Grafton and Henry street areas were made pedestrian-only.

However, Dublin's biggest change happened since the late 1990s, during the "Celtic Tiger" economic boom. The city, which used to have many empty, run-down sites, saw a building boom, especially for new office blocks and apartments. The most striking of these is the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC), a financial district almost a kilometer long along the north quays. While the old tramways were removed in the 1950s, a new Luas tram service started in 2004. Although slow to develop, Dublin Airport became the 16th busiest international airport by 2007.

Dublin in the 21st Century

New Arrivals

Dublin has always been a city where people moved to, and its population steadily grew, even when the rest of Ireland's population fell from the mid-1800s. The city's population doubled in the 1800s to about 400,000 by 1900. It doubled again in the 1900s, reaching almost a million by 1980. However, most people coming to the city were from other parts of Ireland. Many Dubliners also left the city, especially for Britain and the United States, because of high unemployment and a high birth rate.

However, the 21st century saw a big change. Ireland's economic boom, called the "Celtic Tiger," attracted immigrants from all over the world. The largest group at first was Irish people returning home. But there was also a lot of immigration from other countries. By the early 2000s, Dublin became home to large communities of Chinese, Nigerians, Brazilians, Russians, Romanians, and many others, especially from Africa and Eastern Europe. After several Eastern European countries joined the European Union in 2004, Eastern Europeans became the largest immigrant group in Dublin. Poland was the most common country of origin, with over 150,000 young Poles arriving in Ireland since late 2004, mostly in Dublin.

The first wave of immigration to Dublin slowed down during the financial crisis of 2008-2009, which hit Ireland's economy hard. However, as the economy recovered, immigration to Dublin started to increase again, rising sharply in the late 2010s and 2020s. By 2022, the population of County Dublin had grown to over 1.4 million. More than 17% of these residents were born outside Ireland. In inner-city Dublin, the number of foreign-born residents was much higher. For example, in the north inner city, only 36% described themselves as 'white Irish' in the 2022 census. Unlike the earlier wave of migration, most migrants in the late 2010s and 2020s were from outside Europe. The largest groups of foreign citizens are now Brazilians and Indians, followed by Poles and Romanians. After the pandemic, from 2022 onwards, there was also a sharp rise in people seeking asylum, with up to 600 arriving each week in 2024. Many of these people ended up living in temporary camps because no housing was available.

By the 2020s, some negative feelings began to develop towards immigrants, especially asylum seekers in Dublin. There have been many protests against placing migrants in areas like East Wall, Finglas, and Coolock.

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |