Slavery in medieval Europe facts for kids

Slavery in medieval Europe was a common practice across the continent. Europe and North Africa were connected by a busy trade network across the Mediterranean Sea, and this included trading people as slaves. During the Middle Ages (from about 500 to 1500 AD), people captured in wars were often forced into slavery.

As European kingdoms changed into feudal societies, a different group of unfree people called serfs started to replace slaves as the main workforce for farming and the economy. Throughout medieval Europe, the lives and roles of enslaved people varied a lot. Some were stuck doing farm work, while others became trusted advisors to powerful rulers.

Contents

- Early Medieval Slavery

- The Medieval Slave Trade

- Slavery in Law

- Slavery in the Byzantine Empire

- Slavery in the Islamic Near East

- Slavery in Crusader States

- Slavery in Iberia

- Slavery in the Mediterranean

- Slavery in Moldavia and Wallachia

- Slavery in Russia

- Slavery in Poland and Lithuania

- Slavery in Scandinavia

- Slavery in the British Isles

- Serfdom vs. Slavery

Early Medieval Slavery

Slavery in the Early Middle Ages (500–1000 AD) continued many practices from Ancient Rome. It also grew because many people were captured during the chaos of the barbarian invasions of the Western Roman Empire. New laws about slavery spread across Europe, building on old Roman laws. For example, the Welsh laws of Hywel the Good had rules about slaves. In Germanic kingdoms, laws made criminals into slaves. The Visigothic Code said that criminals who couldn't pay fines would become slaves to their victims.

As these people became Christian, the Church worked to reduce the practice of enslaving fellow Christians. St. Patrick, who was once captured and enslaved himself, spoke out against attacks that enslaved new Christians. The return of order and the Church's growing power slowly changed the Roman slave system into serfdom.

Another important person was Bathilde (626–680 AD), who became queen of the Franks. She had been enslaved before marrying Clovis II. When she became ruler, her government made it illegal to trade Christians as slaves throughout the Merovingian empire. Even after the Norman conquest in 1066, about 10% of England's population in the Domesday Book (1086) were slaves. However, it's hard to know exact numbers because the old Roman word for slave (servus) was also used for serfs later on.

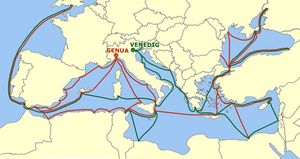

The Medieval Slave Trade

The demand for slaves from the Islamic world, which grew from the 7th century, greatly influenced the slave trade in Europe during the medieval period. For most of this time, selling Christian slaves to non-Christians was forbidden. In a treaty from 840 AD between Venice and the Carolingian Empire, Venice promised not to buy Christian slaves in the Empire or sell them to Muslims. The Church also banned sending Christian slaves to non-Christian lands, for example, at councils in Koblenz (922 AD), London (1102 AD), and Armagh (1171 AD).

Because of these rules, most Christian slave traders focused on moving slaves from non-Christian areas to Muslim Spain, North Africa, and the Middle East. Non-Christian merchants also mostly traded with Muslim markets. Many Arabic silver coins found in Eastern Europe and Southern Sweden suggest trade routes from Slavic lands to Muslim territories, likely for slaves.

Italian Merchants and Slave Trade

By the time of Pope Zachary (741–752 AD), Venice had a busy slave trade. They enslaved people in Italy and other places, selling them to the Moors in North Africa. Pope Zacharias himself reportedly banned this trade from Rome. When selling Christians to Muslims was forbidden, Venetian traders started selling more Slavs and other non-Christian Eastern European slaves through the Balkan slave trade.

Caravans of slaves traveled from Eastern Europe, through places like Prague and Alpine passes in Austria, to reach Venice. An old record from 903–906 AD describes these merchants. Some were Slavic themselves, from Bohemia and the Kievan Rus'. They came from Kiev through Przemyśl, Kraków, Prague, and Bohemia. This record shows that female slaves were valued at about 1.5 grams of gold, while male slaves, who were more common, were worth much less. Eunuchs were especially valuable.

Venice was not the only slave trading center in Italy. Southern Italy had slaves from far-off regions like Greece, Bulgaria, Armenia, and Slavic areas. In the 9th and 10th centuries, Amalfi was a major seller of slaves to North Africa. Genoa, along with Venice, controlled the trade in the Eastern Mediterranean from the 12th century. They also dominated the Black Sea slave trade from the 13th century. They sold Baltic and Slavic slaves, as well as Armenians, Circassians, Georgians, Turks, and other groups from the Black Sea and Caucasus regions to Muslim nations in the Middle East.

Genoa mainly managed the slave trade from Crimea to Mamluk Egypt until the 13th century. Then, Venice gained more control over the Eastern Mediterranean and took over that market. Between 1414 and 1423 alone, at least 10,000 slaves were sold in Venice.

Slavery in Iberia

Al-Andalus, the Muslim-ruled part of the Iberian Peninsula (711–1492 AD), brought in many slaves for its own use. It also served as a place where Muslim and Jewish merchants sold slaves to the rest of the Islamic world. There was a strong demand, especially for men of fighting age, in Umayyad Spain, which needed new Mamluk soldiers.

For example, Al-Hakam I had 5,000 slave soldiers on horseback and 1,000 on foot. These slave soldiers were called Al-haras (the Guard) because they were all Christians or foreigners. They lived in large barracks with stables for their horses.

During the rule of Abd-ar-Rahman III (912–961 AD), there were many Saqaliba, or Slavic slaves, in Córdoba, the capital. Their numbers grew from 3,750 to 13,750. Writers like Ibn Hawqal noted that Jewish merchants from Verdun specialized in trading eunuchs, who were very popular in Muslim Spain.

Historian Roger Collins suggests that while the Vikings' role in the slave trade in Iberia is not fully clear, their raids are well-recorded. Viking attacks on al-Andalus happened in 844, 859, 966, and 971 AD.

Vikings and Slaves

The Nordic countries during the Viking Age (700–1100 AD) practiced slavery. The Vikings called their slaves thralls. There were also other terms for thralls based on gender, like ambatt (female slave) or bryti (someone in charge of food). Some thralls, like Tolir, a bryti, could even marry and manage a king's estate. A muslegoman was a runaway slave. These different names show that thralls had various positions and duties.

A key part of Viking life was capturing and selling people. Most thralls came from Western Europe, including many Franks, Anglo-Saxons, and Celts. Many Irish slaves were brought to Iceland (874–930 AD) when it was settled. Raids on monasteries provided young, educated slaves who could be sold for high prices in Venice or to Byzantium via the Black Sea slave trade.

Viking trade centers stretched east from Hedeby in Denmark and Birka in Sweden to Staraya Ladoga in northern Russia by the late 8th century. Capturing slaves was a result of conflicts. The Annals of Fulda recorded that Franks defeated by Vikings in 880 AD were taken as captives.

This trade continued into the 9th century as Scandinavians set up more trade centers in places like Kaupang in Norway, Novgorod and Kiev in Russia, closer to Byzantium. Dublin and other Viking settlements in northwestern Europe became gateways for trading captives northwards. Thralls could be bought and sold at slave markets. The Laxdoela Saga tells of a meeting of kings every three years on the Branno Islands where slaves were traded.

The 10th-century Persian traveler Ibn Rustah described how Vikings, also called Varangians or Rus, terrorized and enslaved the Slavs they captured along the Volga River. Slaves were often sold south to the Byzantine Empire via the Black Sea slave trade, or to Muslim buyers through routes like the Volga trade route and Khazar slave trade to Central Asia.

People captured during Viking raids in Western Europe, like Ireland, could be sold to Muslim Spain via the Dublin slave trade. Or they could be taken to Hedeby or Brännö and then via the Volga trade route to Russia, where slaves and furs were sold to Muslim merchants for Arab silver coins and silk.

Ahmad ibn Fadlan from Baghdad wrote about Volga Vikings selling Slavic slaves to Middle Eastern merchants. Finland was another source for Viking slave raids. Slaves from Finland or the Baltic states were traded as far as central Asia. Captives could be traded many times within the Viking network. For example, the Irishman St. Findan was bought and sold three times after being captured by Vikings.

Mongols and Slave Trade

The Mongol invasions in the 13th century brought a new force to the slave trade, creating an international slave market. The Mongols enslaved skilled people, women, and children. They marched them to places like Karakorum or Sarai, where they were sold across Eurasia. Many of these slaves were sent to the slave market in Novgorod.

Merchants from Genoa and Venice in Crimea were involved in the slave trade with the Golden Horde. In 1441, Haci I Giray created the Crimean Khanate, independent from the Golden Horde. The Crimean Khanate often raided areas like Poland-Lithuania and Russia for slaves. For each captive, the khan received a share of 10% or 20%. These raids continued until the early 18th century, with a massive slave trade to the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. The Genoese port of Caffa in Crimea was a very important slave market. Crimean Tatar raiders enslaved over 1 million Eastern Europeans.

England and Ireland Slave Trade

In medieval Ireland, slaves were traded like cattle and could even be used as money. In 1102, the Council of London, led by Anselm of Canterbury, passed a rule against the slave trade in England. This rule was mainly aimed at stopping the sale of English slaves to the Irish.

Christians Owning Muslim Slaves

While most slaves were sent to Muslim countries, Christians also owned Muslim slaves. In Southern France in the 13th century, "enslaving Muslim captives was still quite common." Records show Saracen slave girls sold in Marseilles in 1248. This was around the time Seville fell to Christian crusaders, who enslaved many Muslim women as war prizes.

Also, owning slaves was legal in 13th-century Italy. Many Christians held Muslim slaves throughout the country. These Saracen slaves were often captured by pirates and brought to Italy from Muslim Spain or North Africa. In the 13th century, most slaves in the Italian city of Genoa were of Muslim origin. These Muslim slaves were owned by royalty, military groups, and even the Church.

Christians also sold Muslim slaves captured in war. The Knights of Malta attacked pirates and Muslim ships, and their base became a center for slave trading, selling captured North Africans and Turks. Malta remained a slave market until the late 18th century. One thousand slaves were needed to power the ships of the Order.

However, Christian armies were more likely to kill their enemies than to enslave them. Generally, there were relatively few non-Christian slaves in medieval Europe, and this number decreased significantly by the end of the medieval period.

Jewish Slave Trade Role

The role of Jewish merchants in the early medieval slave trade has often been misunderstood. While medieval records show that some Jews owned slaves in medieval Europe, historians like Toch (2013) say that the idea that Jewish merchants were the main slave dealers is based on misreadings of old documents. Jewish writings from that time do not show a large-scale slave trade or slave ownership that was different from the general slavery in early medieval Europe.

Slave Trade Ending in Middle Ages

As more and more of Europe became Christian, and fights between Christian and Muslim nations grew, large-scale slave trade moved to more distant places. Sending slaves to Egypt, for example, was forbidden by the Pope many times between 1317 and 1425. This was because slaves sent to Egypt often became soldiers and ended up fighting their former Christian owners. Even though these repeated bans show that some trade still happened, they also show it became less desirable. In the 16th century, African slaves mostly replaced other enslaved groups in Europe.

Slavery in Law

Secular Law

Slavery was heavily regulated by Roman law, which was organized in the Byzantine Empire by Justinian I into the Corpus Iuris Civilis. This collection of laws was lost in the West for centuries but found again in the 11th and 12th centuries. It led to the creation of law schools in Italy and France. According to these laws, people are naturally free, but the "law of nations" could make some people slaves. The basic definition of a slave in Roman-Byzantine law was:

- Anyone whose mother was a slave.

- Anyone captured in battle.

- Anyone who sold themselves to pay a debt.

However, it was possible to become a freed person or a full citizen. The laws had many complicated rules for freeing slaves.

The slave trade in England was officially ended in 1102. In Poland, slavery was forbidden in the 15th century and replaced by a second period of serfdom. In Lithuania, slavery was formally abolished in 1588.

Church Law

There was a legal reason given for enslaving Muslims, found in the Decretum Gratiani. It said that the Bible mentions Hagar, Abraham's slave girl, was treated harshly by Abraham's wife Sarah. Church law, like Roman law, defined a slave as anyone whose mother was a slave. Otherwise, church laws focused on slavery only in church settings. For example, slaves were not allowed to become clergy.

Slavery in the Byzantine Empire

Slavery in the Islamic Near East

The ancient and medieval Near East includes modern-day Turkey, the Levant, and Egypt. These areas were ruled by either the Byzantines or the Persians at the end of ancient times. Existing Byzantine (Roman) and Persian slavery practices might have influenced how slavery developed in Islamic law. Some scholars also believe that Jewish traditions influenced Islamic legal thinking about slavery.

Many similarities exist between Islamic slavery in the early Middle Ages and the practices of early medieval Byzantines and Western Europeans. Freed slaves under Islamic rule still owed services to their former masters, similar to slavery in ancient Rome and slavery in ancient Greece. However, slavery in the early medieval Near East also grew from practices common among pre-Islamic Arabs.

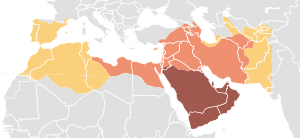

Islamic States and Slavery

Like the Old and New Testaments, and Greek and Roman laws, the Quran accepts slavery. However, it encourages kindness towards slaves and eventually freeing them, especially if they convert to Islam. In the early Middle Ages, many slaves in Islamic society were enslaved for only a short time, perhaps an average of seven years. Like their European counterparts, early medieval Islamic traders preferred slaves who were not of their own religion. They focused on "pagans" from inner Asia, Europe, and especially from sub-Saharan Africa. The practice of freeing slaves may have helped former slaves join wider society. However, under Islamic law, converting to Islam did not automatically mean a slave would be freed.

Slaves worked in heavy labor and in homes. Because Islamic law allowed for concubines, early Islamic traders brought in many female slaves, unlike Byzantine and later European slave traders. The very first Islamic states did not have slave soldiers, but they did include freedmen in their armies. This might have helped the rapid expansion of early Islamic conquests. By the 9th century, using slaves in Islamic armies, especially Turks in cavalry and Africans in infantry, was common.

In Egypt, Ahmad ibn Tulun brought in thousands of black slaves to gain independence from the Abbasid Caliphate in 868 AD. The Ikhshidid dynasty used black slave units to free itself from Abbasid rule in 935 AD. Black professional soldiers were most linked with the Fatimid dynasty, who had more black professional slave soldiers than the previous two dynasties. The Fatimids were the first to include black professional slave soldiers in their cavalry, despite strong opposition from Central Asian Turkish Mamluks.

In the later Middle Ages, as Islamic rule expanded into the Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf, and the Arabian Peninsula, the Saharan-Indian Ocean slave trade grew. This network was a large market for African slaves, transporting about four million African slaves from its start in the 7th century until its end in the 20th century. The strengthening of borders in the Islamic Near East changed the slave trade. Strict Islamic laws and clear borders meant that buying slaves and receiving them as tribute became more common than capturing them. Even the sources of slaves shifted from the Fertile Crescent and Central Asia to Indochina and the Byzantine Empire.

Slaves were used for many tasks, including farming, industry, military service, and domestic work. Women were often preferred over men and usually worked in homes as servants, concubines, or wives. Slaves in homes and businesses were generally better off than those in agriculture. They might become part of the family or business partners, instead of being forced into hard labor. There are some mentions of slave gangs, mostly African, working on drainage projects in Iraq, salt and gold mines in the Sahara, and sugar and cotton farms in North Africa and Spain. However, these references are rare. Eunuchs were the most valued type of slave.

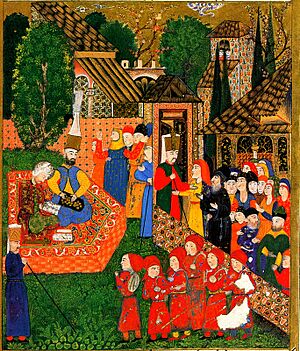

The most fortunate slaves found work in politics or the military. In the Ottoman Empire, the Devşirme system trained young slave boys for government or military service. Young Christian boys were taken from their conquered villages as a tax. They were then employed in government, entertainment, or the army, depending on their skills. Slaves achieved great success through this program. Some became Grand Vizier (a top minister) to the Sultan, and others became Janissaries (elite soldiers).

These men were called kul, or slaves "of the Gate" (meaning the Sultan). While not slaves in the usual sense under Islamic law, these Devşirme alumni remained under the Sultan’s control.

The Islamic Near East relied heavily on professional slave soldiers, who formed the core of armies. Slave units were wanted because they were very loyal to the ruler. Since they were brought in from outside, they could not threaten the throne with local loyalties.

Ottoman Empire Slavery

Slavery was an important part of Ottoman society. The Byzantine-Ottoman wars and the Ottoman wars in Europe brought many Christian slaves into the Ottoman Empire. In the mid-14th century, Murad I created his own personal slave army called the Kapıkulu. This new force was based on the sultan’s right to one-fifth of war prizes, which he said included captives taken in battle. These captured slaves were converted to Islam and trained to serve the sultan personally.

In the devşirme (meaning "blood tax" or "child collection"), young Christian boys from Anatolia and the Balkans were taken from their homes. They were converted to Islam and joined special soldier groups of the Ottoman army. These groups were called Janissaries, the most famous part of the Kapıkulu. The Janissaries became very important in the Ottoman military conquests in Europe.

Most of the Ottoman military commanders, government officials, and actual rulers of the Ottoman Empire, like Pargalı İbrahim Pasha and Sokollu Mehmet Paşa, were recruited this way. By 1609, the Sultan’s Kapıkulu forces grew to about 100,000.

The concubines of the Ottoman Sultan were mainly purchased slaves. Because Islamic law forbade Muslims from enslaving other Muslims, the Sultan’s concubines were generally of Christian origin. The mother of a Sultan, though technically a slave, received the very powerful title of Valide Sultan and sometimes became the actual ruler of the Empire. One famous example was Kösem Sultan, daughter of a Greek Christian priest, who ruled the Ottoman Empire in the early 17th century. Another was Roxelana, the favorite wife of Suleiman the Magnificent.

Slavery in Crusader States

As a result of the crusades, thousands of Muslims and Christians were sold into slavery. Once sold, most were never heard from again, making it hard to find details about their experiences.

In the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, founded in 1099, about 120,000 Franks ruled over 350,000 Muslims, Jews, and local Eastern Christians. After the first invasion and conquest, which sometimes involved massacres or expulsions, a peaceful coexistence usually developed among the three religions. The Crusader states inherited many slaves. Some Muslims captured in war were also added to this group. The Kingdom’s largest city, Acre, had a big slave market. However, most Muslims and Jews remained free. The laws of Jerusalem stated that former Muslim slaves, if they truly converted to Christianity, had to be freed.

Christian law said that Christians could not enslave other Christians, but enslaving non-Christians was allowed. In fact, military groups often enslaved Muslims and used slave labor on their farms. No Christian, whether Western or Eastern, was allowed by law to be sold into slavery. However, this fate was as common for Muslim prisoners of war as it was for Christian prisoners taken by Muslims. Later in the medieval period, some slaves were used to row Hospitaller ships. Generally, there were relatively few non-Christian slaves in medieval Europe, and this number greatly decreased by the end of the medieval period.

The 13th-century Assizes of Jerusalem dealt mostly with runaway slaves and their punishments, banning slaves from testifying in court, and freeing slaves. Slaves could be freed through a will or by converting to Christianity. Conversion was apparently used by Muslims as an excuse to escape slavery, but they would then continue to practice Islam. Crusader lords often refused to let them convert. Pope Gregory IX, against both the laws of Jerusalem and his own church laws, allowed Muslim slaves to remain enslaved even if they converted.

Slavery in Iberia

Communities of Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived on both sides of the divide between Muslim and Christian kingdoms in Medieval Iberia. Al-Andalus had Jewish and Christian communities, while Christian Iberia had Muslim and Jewish communities. Christianity introduced the idea that Christians should not enslave other Christians. This idea was strengthened by Islam's ban on enslaving fellow believers. Also, Islamic law protected Christians and Jews living in Islamic lands from enslavement. This protection also applied to Muslims living in Christian Iberia. Despite these rules, criminals or indebted Muslims and Christians in both regions could still be legally enslaved.

Islamic Iberia and Slave Trade

An early economic support of the Islamic empire in Iberia (Al-Andalus) during the 8th century was the slave trade. Because freeing slaves was seen as a good deed in Islamic law, slavery in Muslim Spain couldn't grow as much from within as in older slave societies. So, Al-Andalus relied on trade to get new enslaved people. By connecting the Umayyads, Khārijites, and 'Abbāsids, the flow of trafficked people from the Sahara to Al-Andalus became a very profitable trade. This constant flow of gold from the slave trade was key to the growth of Islamic business. It was the most successful way to make money. This big change in money use shows a major shift from the earlier Visigothic economy.

The medieval Iberian Peninsula often saw warfare between Muslims and Christians, though sometimes they were allies. Raiding parties from Al-Andalus would attack Christian Iberian kingdoms, taking back treasures and people. For example, in a raid on Lisbon in 1189, the Almohad caliph Yaqub al-Mansur captured 3,000 women and children. His governor of Córdoba took 3,000 Christian slaves in an attack on Silves in 1191. An attack by Alfonso VIII of Castile in 1182 brought him over two thousand Muslim slaves. These raids also included summer attacks (Sa’ifa) by Cordoba. Besides gaining wealth, some Sa’ifa raids aimed to capture mostly male slaves, often eunuchs. They were generally called Saqaliba, the Arabic word for Slavs. Slavs became the most common group in the slave trade by the 10th century, leading to the word "slave" itself. Saqaliba were mostly assigned to palaces as guards, concubines, and eunuchs, though some were privately owned. Along with Christians and Slavs, Sub-Saharan Africans were also enslaved, brought from the Sahara caravan trade. Slaves in Islamic lands were generally used for domestic, military, and administrative purposes, rarely for farming or large factories. Christians living in Al-Andalus were not allowed to have authority over Muslims, but they could own non-Muslim slaves.

Christian Iberia and Slavery

Contrary to what some historians like Marc Bloch thought, slavery was strong in medieval Christian Iberia. Slavery existed under the Romans and continued under the Visigoths. From the 5th to early 8th century, Christian Visigothic Kingdoms ruled large parts of the Iberian Peninsula. Their rulers worked to create laws about human bondage. In the 7th century, King Chindasuinth issued the Visigothic Code, which later Visigothic kings added to. Even though the Visigothic Kingdom fell in the early 8th century, parts of the Visigothic Code were still used in Spain for centuries. The Code, with its frequent focus on the legal status of slaves, shows that slavery continued after Roman rule in Spain.

The Code regulated the social conditions, behavior, and punishments of slaves. Marriage between slaves and free people was forbidden. If a free woman married another person’s slave, the couple would be separated and whipped. If the woman refused to leave the slave, she would become the slave owner's property. Any children born to the couple would also be slaves.

Unlike Roman law, where only slaves could be physically punished, under Visigothic law, people of any social status could be punished physically. However, the beatings given to slaves were always harsher than those given to freed or free people.

Slavery continued in Christian Iberia after the Muslim invasions in the 8th century, and the Visigothic law codes still controlled slave ownership. However, historian William Phillips notes that medieval Iberia was not a "slave society" but a "society that owned slaves." Slaves were a small part of the population and not a major part of the workforce. While slavery continued, its use changed. Ian Wood suggests that under the Visigoths, most slaves lived and worked on rural farms.

After the Muslim invasions, slave owners (especially in the kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia) stopped using slaves as farm laborers or in work gangs, and did not force slaves into military service. Slaves were usually owned individually rather than in large groups. There seem to have been many more female than male slaves, and they were most often used as domestic servants or to help free laborers. In this way, slavery in Aragon was similar to other Christian kingdoms in France and Italy.

In the kingdoms of León and Castile, slavery followed the Visigothic model more closely. Slaves in León and Castile were more likely to be used as farm laborers, replacing free labor to support noble estates. These trends changed after the Black Death in 1348, which greatly increased the demand for slaves across the whole peninsula.

Christians were not the only slaveholders in Christian Iberia. Both Jews and Muslims living under Christian rule owned slaves, though more commonly in Aragon and Valencia than in Castile. After the conquest of Valencia in 1245, the Kingdom of Aragon banned Jews from owning Christian slaves, but they could still own Muslim or pagan slaves. The main role of Iberian Jews in the slave trade was as facilitators: they acted as brokers between Christian and Muslim kingdoms.

This role caused some fear among Christian populations. A letter from Pope Gregory XI in 1239 mentioned rumors that Jews were kidnapping and selling Christian women and children into slavery while their husbands were fighting Muslims. Despite these worries, the main role of Jewish slave traders was to help exchange captives between Muslim and Christian rulers, which was a key part of the economic and political connection between Christian and Muslim Iberia.

In the early period after the fall of the Visigothic kingdom in the 8th century, slaves mainly came into Christian Iberia through trade with the Muslim kingdoms in the south. Most were Eastern European, captured in battles and raids, with the majority being Slavs. However, the types of slaves in Christian Iberia changed over the Middle Ages. Slaveholders in Christian kingdoms gradually stopped owning Christians, following Church rules. In the middle of the medieval period, most slaves in Christian Iberia were Muslim, either captured in battle with Islamic states or brought from the eastern Mediterranean by merchants from cities like Genoa.

The Christian kingdoms of Iberia often traded their Muslim captives back across the border for money or goods. Historian James Broadman writes that this type of redemption offered the best chance for captives to regain their freedom. Selling Muslim captives helped Aragon and Castile pay for the Reconquista. Battles and sieges provided many captives. After the siege of Almeria in 1147, sources say that Alfonso VII of León sent almost 10,000 Muslim women and children from the city to Genoa to be sold into slavery as partial payment for Genoa's help in the campaign.

Towards the end of the Reconquista, this source of slaves became less available. Muslim rulers were less able to pay ransoms, and the Christian capture of large cities in the south made mass enslavement of Muslim populations impractical. The loss of Iberian Muslim slaves encouraged Christians to look for other sources of labor. Starting with the first Portuguese slave raid in sub-Saharan Africa in 1411, the focus of slave imports shifted from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic World. The number of Sub-Saharan Africans among slaves in Christian Iberia began to increase.

Between 1489 and 1497, almost 2,100 black slaves were shipped from Portugal to Valencia. By the end of the 15th century, Spain had the largest population of black Africans in Europe, with a small but growing community of black former slaves. By the mid-16th century, Spain imported up to 2,000 black African slaves annually through Portugal. By 1565, most of Seville’s 6,327 slaves (out of a total population of 85,538) were black Africans.

Slavery in the Mediterranean

In the Mediterranean region, people became enslaved through war, conquest, piracy, and raids along borders. Also, some courts would sentence people to slavery, and some people even sold themselves or their children into slavery because of extreme poverty. The main reason for slavery in the Mediterranean was the greed of the slave traders. Many raids were done just to make money from the captured slaves, with no political or religious goals. Also, governments and religious groups often helped ransom individuals, making piracy a profitable business. This meant some people were returned home, while others were sold far away.

For those who traded in the Mediterranean, the human qualities and intelligence of enslaved people made them valuable goods. To buy a person was to buy their labor, freedom, and faith. Religious conversion was often a reason for these sales. Also, religious differences were the main basis for slave ownership during this time. It was not legal for Christians, Muslims, or Jewish people to enslave fellow believers. However, enslaving and forcing the conversion of non-believers or people from other religions was allowed.

There were markets throughout the Mediterranean where enslaved people were bought and sold. In Italy, the main slave trade centers were Venice and Genoa. In Iberia, they were Barcelona and Valencia. Islands off the Mediterranean, including Majorca, Sardinia, Sicily, Crete, Rhodes, Cyprus, and Chios, also had slave markets. From these markets, merchants would sell enslaved people locally or transport them to places where slaves were in higher demand. For example, the Italian slave market often sold to Egypt to meet the Mamluk demand for slaves. This demand caused Venice and Genoa to compete for control of Black Sea trading ports.

The duties and expectations of slaves varied by location. However, in the Mediterranean, it was most common for enslaved people to work in the homes of wealthy families. Enslaved people also worked in agricultural fields, but this was less common across the Mediterranean. It was most common in Venetian Crete, Genoese Chios, and Cyprus, where enslaved people worked in vineyards, fields, and sugar mills. These were colonial societies, and enslaved people worked alongside free laborers in these areas. Enslaved women were sought after the most and therefore sold at the highest prices. This shows the desire for domestic workers in wealthy households.

Slavery in Moldavia and Wallachia

Slavery existed in what is now Romania, under the Ottoman Empire and Russian Empire, even before the founding of the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia in the 13th–14th centuries. It was gradually abolished in the 1840s and 1850s, before the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia gained independence. Slavery also existed in Transylvania and Bukovina (parts of the Habsburg monarchy and later Austria-Hungarian Empire) until 1783. Most slaves were of Roma (Gypsy) ethnicity, and a significant number of Rumâni were in serfdom slavery.

Historian Nicolae Iorga linked the Roma people’s arrival to the 1241 Mongol invasion of Europe and thought their slavery was a leftover from that time. The practice of enslaving prisoners might also have come from the Mongols. The ethnic background of the "Tatar slaves" is unknown; they could have been captured Tatars of the Golden Horde, Cumans, or slaves of Tatars and Cumans.

While some Romani people might have been slaves or helpers of the Mongols or Tatars, most of them came from south of the Danube in the late 14th century, before Wallachia was founded. Roma slaves were owned by the boyars (nobles), Christian Orthodox monasteries, or the state. They were used only as smiths, gold panners, and farm workers.

The Rumâni were only owned by Boyars and Monasteries until Romania gained independence from the Ottoman Empire on May 9, 1877. They were considered less valuable because they had to pay taxes, were only skilled at farm work, and could not be used as tribute. It was common for both boyars and monasteries to register their Romanian serfs as "Gypsies" so they wouldn't have to pay the taxes imposed on serfs. Any Romanian, male or female, marrying a Roma person would immediately become a slave who could be used as tribute.

Slavery in Russia

In Kievan Rus' and Russia, slaves were usually called kholops. A kholop's master had complete power over their life: they could kill them, sell them, or use them to pay a debt. However, the master was legally responsible for their kholop’s actions. A person could become a kholop by being captured, selling themselves, being sold for debts or crimes, or marrying a kholop. Until the late 10th century, kholops made up most of the workers on noble lands.

By the 16th century, slavery in Russia mostly involved people who sold themselves into slavery due to poverty. They worked mainly as household servants for the richest families and often produced less than they consumed. Laws forbade freeing slaves during famines to avoid feeding them, and slaves generally stayed with the family for a long time. The Domostroy, an advice book, talks about choosing slaves with good character and providing for them properly. Slavery remained a major institution in Russia until 1723, when Peter the Great changed household slaves into house serfs. Russian farm slaves were formally changed into serfs earlier, in 1679.

In 1382, the Golden Horde under Tokhtamysh attacked Moscow, burning the city and taking thousands of people as slaves. For years, the khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan regularly raided Russian lands for slaves and to plunder towns. Russian records show about 40 raids by Kazan khans on Russian territories in the first half of the 16th century. In 1521, the combined forces of Crimean khan Mehmed I Giray and his Kazan allies attacked Moscow and captured thousands of slaves. About 30 major Tatar raids were recorded into Muscovite territories between 1558 and 1596. In 1571, the Crimean Tatars attacked and sacked Moscow, burning everything but the Kremlin and taking thousands of captives as slaves for the Crimean slave trade. In Crimea, about 75% of the population consisted of slaves.

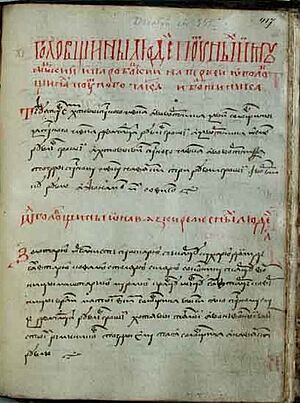

Slavery in Poland and Lithuania

Slavery in Poland existed in the Kingdom of Poland during the time of the Piast dynasty. However, slavery was limited to those captured during war. In some special cases and for limited periods, serfdom was also applied to people who owed debts.

Slavery was officially banned in 1529. The ban on slavery was one of the most important parts of the Statutes of Lithuania, which had to be put into effect before the Grand Duchy of Lithuania could join the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569.

The First Statute was written in 1522 and became law in 1529. It was started by the Lithuanian Council of Lords. It is thought that the law was a rewritten and expanded version of the 15th-century Casimir's Code.

Evidence shows that slavery in Scandinavia was more common in the southern regions. There are fewer laws about slavery in the northern provinces. Slaves were likely numerous but owned by wealthy people as workers on large farms.

Laws from the 12th and 13th centuries describe the legal status of two types of slaves. According to the Norwegian Gulating code (around 1160), domestic slaves could not be sold out of the country, unlike foreign slaves. This and other laws defined slaves as their master’s property, similar to cattle. If either was harmed, the person who caused the harm was responsible for damages. But if either caused damage to property, the owners were held responsible. The laws also described how a slave could be freed. According to the Law of Scania, slaves could be granted freedom or buy it themselves. After being freed, they had to be accepted into a new family group or face being outcast from society.

The Law of Scania indicates that free men could become slaves as a way to make up for a crime, with the idea that they would eventually be freed. Similarly, the Gotlander Guta Lag shows that slavery could be for a set time and a way to pay off debt. In the Older Västgöta Law, widows were only allowed to remarry if an enslaved fostre (male) or fostra (female) could manage the farm in her absence. The Younger Västgöta Law shows even more trust for fostre and fostra, as they could sometimes be trusted with the master’s keys. Some fostre were even trusted enough to take part in military actions while still slaves. However, despite their independence, any children of fostre or fostra were still the property of their masters.

A freed slave did not have full legal rights. For example, the punishment for killing a former slave was low. A former slave’s son also had a low status, but higher than his parents. Women were often taken as slaves and forced to be concubines for lords. The children of these women had few formal rights regarding inheritance, though legitimacy was possible if they were needed for succession or favored by their parents, but nothing was guaranteed.

Slavery began to be replaced by a feudal system where free men tied to the land worked farms for a lord, reducing the need for slaves. The Norwegian law code from 1274, Landslov (Land’s law), does not mention slaves, but only former slaves. This suggests that slavery was abolished in Norway by this time. In Denmark, slavery was gradually replaced by serfdom in the 13th century. In Sweden, slavery was abolished in 1334 and was not replaced with serfdom, which never existed there.

Slavery in the British Isles

British Wales and Gaelic Ireland and Scotland were among the last parts of Christian Europe to give up slavery. Under Gaelic custom, prisoners of war were regularly taken as slaves. During the time when slavery was disappearing across most of Western Europe, it was reaching its peak in the British Isles. With the Viking invasions and the wars between Scandinavians and natives, the number of captives taken as slaves greatly increased. The Irish church strongly opposed slavery and blamed the 1169 Norman invasion on God's punishment for the practice, along with local acceptance of having multiple wives and divorce.

Serfdom vs. Slavery

When historians study how serfdom developed from slavery, they face several challenges. Some historians believe that slavery changed into serfdom (an idea that's only about 200 years old), though they disagree on how quickly this happened. Pierre Bonnassie, a medieval historian, thought that the old form of slavery ended in Europe by the 10th century and was replaced by feudal serfdom. Jean-Pierre Devroey thinks the shift from slavery to serfdom was also gradual in some parts of the continent. However, other areas, like the rural parts of the Byzantine Empire, Iceland, and Scandinavia, did not have what he calls "western-style serfdom" after slavery ended. This issue is complicated because regions in Europe often had both serfs and slaves at the same time. In northwestern Europe, slavery changed to serfdom by the 12th century. The Catholic Church encouraged this change by setting an example. Enslaving fellow Catholics was forbidden in 992, and freeing slaves was declared a good religious act. However, it remained legal to enslave people of other religions.

Generally speaking, the basic differences between slaves and serfs are debated. Dominique Barthélemy and others have questioned whether it's easy to tell serfdom from slavery, arguing that a simple classification hides many levels of servitude. Historians are especially interested in the role of serfdom and slavery within the state, and what that meant for both serfs and slaves. Some think that slavery meant people were excluded from public life and its systems, while serfdom was a complex form of dependence that usually didn't have clear legal rules. Wendy Davies argues that serfs, like slaves, were also excluded from the public justice system, and their legal matters were handled in their lords' private courts.

Despite the scholarly disagreement, we can form a general idea of slavery and serfdom. Slaves typically owned no property and were, in fact, the property of their masters. Slaves worked full-time for their masters and were motivated by negative incentives; in other words, if they didn't work, they faced physical punishment. Serfs held plots of land, which was like a "payment" from the lord for the serf’s service. Serfs worked part-time for their masters and part-time for themselves. They had chances to save personal wealth, which slaves often did not.

Slaves were generally brought from foreign countries or continents through the slave trade. Serfs were usually native Europeans and were not forced to move like slaves. Serfs worked in family units, while the idea of family was often less clear for slaves. At any moment, a slave’s family could be torn apart by trade, and masters often used this threat to make slaves obey.

The end of serfdom is also debated. Georges Duby points to the early 12th century as a rough end point for "serfdom in the strict sense." Other historians disagree, citing discussions and mentions of serfdom as an institution at later dates (like in 13th-century England, or in Central Europe, where serfdom grew as it declined in Western Europe). There are several ways to figure out the timeline for this change. One way is by looking at how words were used. There is supposedly a clear change in how people referred to slaves or serfs around 1000 AD, though there isn't full agreement on how significant this change is, or if it even exists.

Also, experts who study coins (numismatists) shed light on the decline of serfdom. There's a common idea that the introduction of money sped up the decline of serfdom because it was better to pay for labor than to rely on feudal duties. Some historians argue that landlords started selling serfs their land – and thus their freedom – during times of economic inflation across Europe. Other historians argue that slavery ended because royalty gave serfs freedom through laws, trying to increase their tax base.

The absence of serfdom in some parts of medieval Europe raises questions. Devroey thinks it's because slavery in these areas wasn't born out of economic needs, but was more of a social practice. Heinrich Fichtenau points out that in Central Europe, there wasn't a strong enough labor market for slavery to become necessary.

|

- Catholic Church and slavery

- Christianity and slavery

- History of slavery

- Islamic views on slavery

- Slavery in ancient Greece

- Slavery in ancient Rome

- Slavery in antiquity

- The Bible and slavery

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |