History of Nicaragua facts for kids

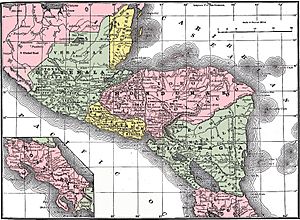

Nicaragua is a country in Central America, located between Mexico and Colombia. It has a coast on the Caribbean Sea to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Honduras is to its north, and Costa Rica is to its south. Nicaragua also has several islands in the Caribbean Sea.

The name Nicaragua comes from "Nicarao," the name of a tribe that lived near Lake Nicaragua before the Spanish arrived. It also includes the Spanish word agua, meaning water, because of the large lakes like Lake Nicaragua (also called Cocibolca) and Lake Managua (or Xolotlán), plus many rivers and lagoons.

Contents

Ancient Nicaragua

Long ago, the eastern part of Nicaragua was home to groups who spoke Misumalpan and Chibchan languages. These people lived in large family groups or tribes. They found food by hunting, fishing, and using a farming method called slash-and-burn, where they cleared land by burning plants. Their main foods were crops like cassava and pineapples. It seems these people traded with and were influenced by the native groups of the Caribbean, as they often used round, thatched huts and canoes, which were common in the Caribbean.

When the Spanish arrived in western Nicaragua in the early 1500s, they found three main tribes, each with its own culture and language: the Niquirano, the Chorotega, and the Chontal. Each group had its own independent chiefs who ruled based on their customs. Their weapons were made of wood, like swords, spears, and arrows. Most tribes were ruled by a chief, or cacique, who was the supreme leader. Laws were shared by royal messengers who visited each town.

The Niquirano people lived between Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific Coast. Their rich chief, Nicarao, lived in Nicaraocali, which is now the city of Rivas. They spoke a language similar to Nahuat and had moved from El Salvador around 1200 CE, originally from Central Mexico. The Chorotegas, also called Mangue, lived in the central region. They are also thought to have come from Central Mexico or Oaxaca, between 600 and 700 CE. These two groups mixed a lot with the Spanish conquerors, leading to the mixed-race people known as mestizos today. The Chontal (meaning "foreigner" in Nahuatl), also known as the Caribs, lived in the central mountains. This group was smaller, and it's not known when they first settled in Nicaragua.

In the west and highland areas where the Spanish settled, many native people died from new diseases brought by the Spaniards, as they had no protection against them. The remaining native people were often forced into labor. Most native groups survived in the east, where Europeans did not settle. The English gave guns to one local group, the Bawihka, who lived in northeast Nicaragua. The Bawihka later married runaway slaves from British Caribbean lands. This new group, called the Miskito, had better weapons and expanded their territory, pushing other native groups further inland. The displaced groups were called the Mayangna.

Spanish Arrival

Europeans first saw Nicaragua when Christopher Columbus sailed along its eastern coast on his fourth voyage in 1502. On September 14, 1502, he reached the mouth of the Río Coco and named it Cabo Gracias a Dios. Eleven days later, on September 25, Columbus arrived at what is now the Mosquito Coast. He described the people he met as "good-natured, very sharp, [and] wanting to see." Columbus also noted seeing "hogs and big mountain cats" and that the people "had threaded cotton" and "their faces painted."

In 1522, the first Spaniards entered the region that would become Nicaragua. Gil González Dávila and a small group reached the western part after traveling through Costa Rica. He explored the fertile western valleys and was impressed by the native civilizations he found. He and his small army collected gold and baptized many native people. Eventually, they pushed the native people too far, and were attacked, almost being wiped out. González Dávila returned to Panama and reported his findings, naming the area Nicaragua. However, the governor, Pedrarias Dávila, tried to arrest him and take his treasures, so González Dávila had to flee.

Within a few months, several Spanish forces, each led by a conquistador, invaded Nicaragua. González Dávila came from the Caribbean coast of Honduras. Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, sent by the governor of Panama, came from Costa Rica. Pedro de Alvarado and Cristóbal de Olid, sent by Hernán Cortés, came from Guatemala through San Salvador and Honduras.

Córdoba seemed to want to build settlements. In 1524, he established permanent towns, including two of Nicaragua's main cities: Granada on Lake Nicaragua and León west of Lake Managua. But he soon had to defend these cities and fight against the other conquistadors.

The fighting between the Spanish forces greatly harmed the native population. Their civilization was destroyed. These battles became known as The War of the Captains. By 1529, Nicaragua was fully conquered. Some conquistadors won, while others were killed. Pedrarias Dávila was one of the winners. He moved to Nicaragua and made León his base.

The land was divided among the conquistadors. The western part was the most desired, with its fertile valley, large freshwater lakes, volcanoes, and lagoons. Many native people were soon forced to work on these "estates." Others were sent to work in mines in northern Nicaragua, but most were sent as slaves to Panama and Peru, bringing great wealth to the new Spanish landowners. Many native people died from disease and neglect by the Spaniards, who controlled everything they needed to survive.

From Colony to Independent State

In 1538, the Viceroyalty of New Spain was created, covering all of Mexico and Central America, except Panama. By 1570, the southern part of New Spain became the Captaincy General of Guatemala. Nicaragua was divided into administrative areas with León as the capital. In 1610, the Momotombo volcano erupted, destroying the capital, which was then rebuilt northwest of its original spot. Meanwhile, Nicaragua's Pacific Coast became a stop on the trade route between Manila, Philippines, and Acapulco, Mexico, known as the Manila galleon trade route.

Nicaragua's history remained fairly quiet for three hundred years after the conquest. There were small civil wars and rebellions, but they were quickly stopped. The region was often raided by Dutch, French, and British pirates. The city of Granada was attacked twice, in 1658 and 1660.

Fight for Independence

Nicaraguans were divided about whether to stay under Spanish rule or become independent. In 1811, a priest named Nicolás García Jerez tried to make agreements with those who wanted independence. He suggested holding elections to form a government council. However, he soon declared himself governor and threatened to punish rebellions with death.

The people of León were the first to act against the Spanish monarchy, overthrowing their local leader on December 13, 1811. Granada followed, demanding that Spanish officials leave. The Spanish constitution of 1812 gave more freedom to local governments, and García Pérez was appointed as the leader of Nicaragua.

In 1821, Guatemala declared its independence, and all Central American provinces followed. Nicaragua became part of the First Mexican Empire in 1822. Then, in 1823, it joined the United Provinces of Central America. Finally, in 1838, Nicaragua became an independent republic. The Mosquito Coast, based in Bluefields on the Atlantic, was claimed by the United Kingdom as a protected area from 1655 to 1850. This area was given to Honduras in 1859 and then to Nicaragua in 1860, though it remained mostly independent until 1894.

Much of Nicaragua's politics after independence was shaped by the rivalry between the liberal leaders of León and the conservative leaders of Granada. This rivalry often led to civil war, especially in the 1840s and 1850s. In 1855, a US adventurer named William Walker was invited by the Liberals to help them against the Conservatives. He declared himself President in 1856 and made English the official language. Honduras and other Central American countries united to force him out of Nicaragua in 1857. After this, Conservatives ruled for three decades. Walker was executed in neighboring Honduras on September 12, 1860.

In 1893, José Santos Zelaya led a liberal uprising and came to power. Zelaya ended the long dispute with the United Kingdom over the Atlantic coast in 1894, bringing the Mosquito Coast fully into Nicaragua.

US Involvement

Because Nicaragua was strategically important, the United States (US) often intervened militarily to protect its interests. Here are some examples:

- 1894: Bluefields was occupied for a month.

- 1896: Marines landed in the port of Corinto.

- 1898: Marines landed at the port of San Juan del Sur.

- 1899: Marines landed at the port of Bluefields.

- 1907: A "Dollar Diplomacy" protectorate was set up, meaning the US used its financial power to influence the country.

- 1910: Marines landed in Bluefields and Corinto.

- 1912-1933: There was bombing, a 20-year occupation, and fighting against rebel groups.

- 1981-1990: The CIA supported a rebel group (Contras) and placed mines in harbors against the government.

US Occupation (1909–1933)

In 1909, the US supported conservative forces who were rebelling against President Zelaya. The US was interested in a possible Nicaragua Canal, worried about Nicaragua causing instability, and Zelaya's attempts to control foreign access to Nicaragua's natural resources. On November 17, 1909, two Americans were executed by Zelaya's order after they admitted to planting a mine in the San Juan River. The US said it intervened to protect American lives and property. Zelaya resigned later that year.

In August 1912, Nicaragua's President, Adolfo Díaz, asked his Secretary of War, General Luis Mena, to resign. Mena fled, and the rebellion grew. When the US asked President Díaz to keep American citizens and property safe, Díaz said he couldn't and asked the US government to protect everyone in the country with its forces.

US Marines were stationed in Nicaragua from 1912 to 1933, except for nine months in 1925. From 1910 to 1926, the conservative party ruled Nicaragua. The Chamorro family, who had long been powerful in the party, largely controlled the government. In 1914, the Bryan–Chamorro Treaty was signed, giving the US control over the proposed canal and leases for possible canal defenses.

Nicaraguan Civil War (1926–1927)

After US forces left in 1925, another violent conflict between liberals and conservatives, known as the Constitutionalist War, began in 1926. Liberal soldiers in the Caribbean port of Puerto Cabezas revolted against Conservative President Adolfo Díaz, who had recently been put in power due to US influence after a coup. The leader of this revolt, Gen. José María Moncada, supported the claim of exiled Liberal vice-president Juan Bautista Sacasa, who arrived in Puerto Cabezas in December and declared himself president of a "constitutional" government. The US, threatening military action, forced the Liberal generals to agree to a cease-fire.

On May 4, 1927, representatives from both sides signed the Pact of Espino Negro, negotiated by Henry Stimson, a special envoy from US President Calvin Coolidge. Under this agreement, both sides agreed to disarm, Díaz would finish his term, and a new national army, the Guardia Nacional (National Guard), would be created. US soldiers would stay to supervise the upcoming November presidential election. A US army battalion arrived to enforce the agreement.

1927–1933

The only Nicaraguan general who refused to sign this pact was Augusto César Sandino. He went into the northern mountains and led a continuous guerrilla war, first against the Conservative government and then against the US Marines. The Marines left in 1933 because of Sandino's war and the Great Depression. When they left, they set up the National Guard, a combined military and police force trained and equipped by the Americans to be loyal to US interests. Anastasio Somoza García, a close friend of the American government, was put in charge. He became one of the country's three main leaders, along with Sandino and the mostly symbolic President Juan Bautista Sacasa.

Sandino and the newly elected Sacasa government made an agreement: Sandino would stop his guerrilla activities in exchange for forgiveness, land for a farming community, and keeping a group of 100 armed men for a year.

Later, the Nicaraguan Campaign Medal was given to American service members who served in Nicaragua during these years.

Growing tension between Sandino and Anastasio Somoza García, the head of the National Guard, led Somoza to order Sandino's assassination. Fearing future armed opposition from Sandino, Somoza invited him to a meeting in Managua, where Sandino was killed by the National Guard on February 21, 1934. After Sandino's death, hundreds of men, women, and children were also killed.

Somoza Family Rule (1936–1979)

Anastasio Somoza García's Leadership

After Sandino's death, Somoza used his National Guard troops to force Sacasa to resign. Somoza took control of the country in 1937 and crushed any possible armed resistance. The Somoza family would rule Nicaragua until 1979.

Early opposition to Somoza came from educated middle-class people and wealthy conservatives, like Pedro Joaquín Chamorro. On September 21, 1956, a Nicaraguan poet, Rigoberto López Pérez, snuck into a party where the President was and shot him. Somoza died a few days later in a US hospital.

Somoza's Rise to Power

Divisions among the Conservative Party in the 1932 elections allowed the Liberal Juan Bautista Sacasa to become president. This made his presidency weak, which was not a problem for Somoza as he built his influence over Congress and the ruling Liberal Party. President Sacasa's popularity dropped because of his poor leadership and accusations of cheating in the 1934 elections. Somoza García benefited from Sacasa's weakening power. He brought together the National Guard and the Liberal Party to win the 1936 presidential elections.

In early 1936, Somoza openly challenged President Sacasa by using military force to remove local government officials loyal to the president and replacing them with his own allies. Somoza García's increasing military actions led to Sacasa's resignation on June 6, 1936. Congress appointed Carlos Brenes Jarquín, an ally of Somoza García, as temporary president and postponed presidential elections until December. In November, Somoza resigned as head of the National Guard, meeting the rules to run for president. The Nationalist Liberal Party (PLN) was formed with support from some Conservatives to back Somoza García. Somoza was elected president in December, reportedly winning with 64,000 out of 80,663 votes. On January 1, 1937, he again took control of the National Guard, holding both the president's role and the military chief's role.

After winning the December 1936 elections, Somoza consolidated his power within the National Guard and divided his political opponents. Somoza family members and close friends took important positions in the government and military. The Somoza family also controlled the PLN, which in turn controlled the legislature and courts, giving Somoza complete power over all parts of Nicaraguan politics. Minor political opposition was allowed as long as it didn't threaten the ruling group. Somoza García's National Guard stopped serious political opposition and anti-government protests. The National Guard's power grew in most government-owned businesses, eventually controlling national radio and telegraph, postal and immigration services, health services, tax collection, and national railroads.

Less than two years after his election, Somoza García declared he intended to stay in power beyond his presidential term, ignoring the Conservative Party. So, in 1938, Somoza García created a Constituent Assembly that gave the president vast power and elected him for another eight-year term. This assembly also extended the presidential term from four to six years and allowed the president to make laws about the National Guard without asking Congress. This ensured Somoza's complete control over the state and military. Control over elections and law-making created a lasting dictatorship.

In 1941, during World War II, Nicaragua declared war on Germany. Somoza didn't send troops to battle but used the crisis to take valuable properties owned by German-Nicaraguans, like the Montelimar estate. Today, it's a private luxury resort. Nicaragua was the first country to approve the UN Charter.

Younger Somozas

Somoza García was followed by his two sons. Luis Somoza Debayle became President (1956-1963) and was effectively the country's dictator until his death. His brother, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, held great power as head of the National Guard. Anastasio, who graduated from West Point, was even closer to the Americans than his father. Luis Somoza, remembered by some as being moderate, was in power for only a few years before dying of a heart attack.

Revolutionaries opposing the Somozas were greatly strengthened by the Cuban Revolution. The revolution gave them hope, inspiration, weapons, and money. Operating from Costa Rica, they formed the Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional (FSLN) and became known as Sandinistas. They took their name from the legendary Augusto César Sandino. With help from the United States, the Somoza brothers managed to defeat these rebels.

Then came President René Schick, whom most Nicaraguans saw as "nothing more than a puppet of the Somozas." President Luis Somoza Debayle, under pressure from the rebels, announced that national elections would be held in February 1963. Election reforms were made, including secret ballots and an election commission, though the Conservative Party never elected members to the commission. Somoza also introduced a constitutional amendment that would prevent family members from taking his place. The opposition was very doubtful of Somoza's promises, and ultimately, control of the country passed to Anastasio Somoza Debayle.

In 1961, a young student named Carlos Fonseca honored Sandino's memory and founded the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN). The FSLN was a small party for most of the 1960s. However, Somoza's hatred of it and his harsh treatment of anyone suspected of being a Sandinista supporter made many ordinary Nicaraguans believe the Sandinistas were much stronger than they actually were.

Somoza gained control of key industries needed to rebuild the nation, not allowing other wealthy people to share in the profits from the growing economy. This eventually weakened Somoza, as even the economic elite were unwilling to support him. In the 1950s, a synthetic type of cotton, one of Nicaragua's main economic products at the time, was developed. This caused cotton prices to drop, hurting the economy greatly.

Landless peasants worked on large farms during short harvest seasons and earned very low wages, sometimes as little as US$1 per day. In desperation, many of these poor workers moved east, looking for their own land near the rainforest. In 1968, the World Health Organization found that polluted water caused 17% of all deaths in Nicaragua.

American Economic Involvement

From 1945 to 1960, the US-owned Nicaraguan Long Leaf Pine Company (NIPCO) paid the Somoza family millions of dollars. In return, the company received benefits, such as not having to replant trees in clear-cut areas. By 1961, NIPCO had cut down all commercially valuable coastal pines in northeast Nicaragua. The growth of cotton farms in the 1950s and cattle ranches in the 1960s forced peasant families from the lands they had farmed for decades. Some were forced by the National Guard to move to new settlements in the rainforest.

Some people moved eastward into the hills, where they cleared forests to plant crops. However, Soil erosion forced them to leave their land and move deeper into the rainforest. Cattle ranchers then claimed the abandoned land. Peasants and ranchers continued this movement deeper into the rainforest. By the early 1970s, Nicaragua had become the United States' top beef supplier. This beef supported fast-food chains and pet food production. President Anastasio Somoza Debayle owned the largest slaughterhouse in Nicaragua, as well as six meat-packing plants in Miami.

Also in the 1950s and 1960s, 40% of all US pesticide exports went to Central America. Nicaragua and its neighbors widely used chemicals banned in the US, such as DDT, endrin, dieldrin, and lindane. In 1977, a study showed that mothers living in León had 45 times more DDT in their breast milk than the World Health Organization's safe level.

Sandinista Uprising (1972–1979)

A major turning point was the December 1972 Managua earthquake that killed over 10,000 people and left 500,000 homeless. A lot of international aid was sent to the country. Some Nicaraguan historians say the earthquake that destroyed Managua was the final blow for Somoza; about 90% of the city was ruined. Somoza's clear corruption, his poor handling of the aid (which led Pittsburgh Pirates star Roberto Clemente to fly to Managua to help, a flight that ended in his death), and his refusal to rebuild Managua, caused many young, unhappy Nicaraguans to join the Sandinistas, as they felt they had nothing left to lose. The Sandinistas received some support from Cuba and the Soviet Union.

On December 27, 1974, a group of nine FSLN guerrillas attacked a party at the home of a former Minister of Agriculture. They killed him and three guards while taking several important government officials and businessmen hostage. In exchange for the hostages, they got the government to pay a US$2 million ransom, broadcast an FSLN message on the radio and in the opposition newspaper La Prensa, release fourteen FSLN members from jail, and fly the attackers and released FSLN members to Cuba. Archbishop Miguel Obando y Bravo helped negotiate.

This event embarrassed the government and greatly boosted the FSLN's reputation. Somoza, in his writings, called this action the start of a sharp increase in Sandinista attacks and government responses. Martial law was declared in 1975, and the National Guard began to destroy villages in the jungle suspected of supporting the rebels. Human rights groups criticized these actions, but US President Gerald Ford refused to end the US alliance with Somoza.

The country fell into a full civil war with the 1978 murder of Pedro Chamorro, who had opposed violence against the government. 50,000 people attended his funeral. Many believed Somoza had ordered his killing. A nationwide strike, including workers and businesses, began in protest, demanding an end to the dictatorship. At the same time, the Sandinistas increased their guerrilla activities. Several towns, with help from Sandinista guerrillas, drove out their National Guard units. Somoza responded with more violence and repression. When León became the first city to fall to the Sandinistas, he ordered the air force to "bomb everything that moves until it stops moving."

The US media reported more and more negatively on the situation in Nicaragua. Realizing that the Somoza dictatorship couldn't last, the Carter administration tried to force him to leave Nicaragua. Somoza refused and tried to keep his power through the National Guard. At that point, the US ambassador sent a message to the White House saying it would be "ill-advised" to stop the bombing, because doing so would help the Sandinistas gain power.

In the end, President Carter refused Somoza further US military aid, believing that the government's harsh rule had led to popular support for the Sandinista uprising.

In May 1979, another general strike was called, and the FSLN launched a major effort to take control of the country. By mid-July, they had Somoza and the National Guard trapped in Managua.

Sandinista Period (1979–1990)

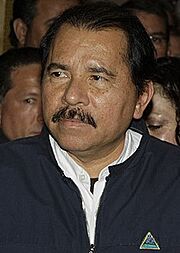

As Nicaragua's government collapsed and the National Guard commanders escaped with Somoza, the US first promised and then denied them refuge in Miami. The rebels advanced on the capital victoriously. On July 19, 1979, a new government was announced under a temporary junta led by 33-year-old Daniel Ortega, and included Violeta Chamorro, Pedro's widow. Somoza eventually ended up in Paraguay, where he was killed in September 1980.

The United Nations estimated the damage from the revolutionary war to be US$480 million. The FSLN took over a nation struggling with poor nutrition, disease, and pesticide contamination. Lake Managua was considered dead due to decades of pesticide runoff, toxic chemical pollution from factories, and untreated sewage. Soil erosion and dust storms were also problems in Nicaragua at the time because of deforestation. To deal with these issues, the FSLN created the Nicaraguan Institute of Natural Resources and the Environment.

The Sandinistas' main large-scale programs included a National Literacy Crusade from March to August 1980. Nicaragua gained international recognition for improvements in literacy, health care, education, childcare, unions, and land reform.

Managua became the second capital in the Americas, after Cuba, to host an embassy from North Korea. Due to tensions between their Soviet supporters and China, the Sandinistas allowed Taiwan to keep its mission and refused to allow a Chinese mission in the country.

The Sandinistas won the national election on November 4, 1984, getting 67% of the votes. Most international observers said the election was "free and fair." The Nicaraguan political opposition and the Reagan administration claimed the government placed restrictions on the opposition. The main opposition candidate was the US-backed Arturo Cruz, who was pressured by the United States government not to participate in the 1984 elections. Later, US officials were quoted saying, "the (Reagan) Administration never considered letting Cruz stay in the race, because then the Sandinistas could rightfully claim that the elections were legitimate." Three right-wing opposition parties boycotted the election, saying the Sandinistas were controlling the media and that the elections might not be fair. Other opposition parties, like the Conservative Democratic Party and the Independent Liberal party, were free to criticize the Sandinista government and take part in the elections. Ortega won, but the long years of war had severely damaged Nicaragua's economy.

US-backed Contras

American support for the long rule of the Somoza family had made relations difficult. The FSLN government was committed to a socialist idea, and many Sandinista leaders continued long-standing relationships with the Soviet Union and Cuba. US President Jimmy Carter, who had stopped aid to Somoza's Nicaragua the previous year, initially hoped that continued American aid to the new government would prevent the Sandinistas from forming a strict socialist government allied with the Soviet bloc. However, the Carter administration's aid was minimal, and the Sandinistas turned to Cuban and Eastern European help to build a new army of 75,000, including tanks, heavy artillery, and attack helicopters, making the Sandinista Army more powerful than its neighbors. The Soviets also promised to provide fighter jets, but they were never delivered.

With the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, relations between the United States and the Sandinista government became a key part of the Cold War. The Reagan administration emphasized the "Communist threat" posed by the Sandinistas, especially reacting to the support given to the Sandinistas by Cuba and the Soviets. The US stopped aid due to evidence that the Sandinistas were supporting rebels in El Salvador. Before the US stopped aid, FSLN politician Bayardo Arce stated that "Nicaragua is the only country building its socialism with the dollars of imperialism." The Reagan administration responded by putting economic penalties and a trade embargo on Nicaragua in 1981, which lasted until 1990.

After a short period of sanctions, Nicaragua faced a collapsing economy. The US trained and funded the Contras, a counter-revolutionary group based in neighboring Honduras, to fight against the Sandinista government. President Reagan called the Contras "the moral equivalent of our founding fathers." The Contras, groups of Somoza's National Guard who had fled to Honduras, were organized, trained, and funded by the CIA. The Contra leaders included some former National Guardsmen, like Contra founder Enrique Bermúdez, and others, like former Sandinista hero Edén Pastora, who disagreed with the Sandinistas' socialist direction. The Contras operated from camps in Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. They carried out a planned campaign of terror among the rural Nicaraguan population to disrupt the Sandinistas' social reform projects.

US support for the Contras was widely criticized around the world, including within Nicaragua and the US, by Democrats in Congress.

The Sandinistas were also accused of human rights abuses. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights investigated abuses by Sandinista forces, including the killing of 35 to 40 Miskitos in December 1981, and the killing of 75 people in November 1984.

American pressure against the government grew throughout 1983 and 1984. The Contras began a campaign of economic damage and disrupted shipping by placing underwater mines in Nicaragua's Port of Corinto. This action was later called illegal by the International Court of Justice.

Daniel Ortega was elected president in 1984. The years of war and Nicaragua's economic situation had severely harmed the country. The US Government offered a political program that gave visas to any Nicaraguan without question. Many Nicaraguans, especially wealthy ones or those with family in the US, left the country in the largest emigration in Nicaraguan history. On May 1, 1985, Reagan issued an order that put a full economic embargo on Nicaragua, which stayed in place until March 1990.

Nicaragua won a historic case against the US at the International Court of Justice in 1986 (see Nicaragua v. United States). The US was ordered to pay Nicaragua $12 billion for violating Nicaraguan independence by attacking it. The United States withdrew its acceptance of the Court, arguing it had no authority in matters between sovereign states. The United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution to pressure the US to pay. Only Israel and El Salvador, which was supported in its own guerrilla uprising, voted with the US. Jeane Kirkpatrick, the American ambassador to the UN, criticized the Court as a "semi-judicial" body. The US also noted that Cuba and the Soviet Union had earlier committed similar violations against Nicaraguan independence by providing training and weapons to the Sandinistas against the Somoza government.

The International Court of Justice decision described the conflict in Nicaragua as an act of aggression by a foreign power against Nicaragua. In a 12 to 3 vote, the Court's judgment against the United States stated that by: ...training, arming, equipping, financing and supplying the contra forces or otherwise encouraging, supporting and aiding military and paramilitary activities in and against Nicaragua, the United States has acted, against the Republic of Nicaragua, in breach of its obligation under customary international law not to intervene in the affairs of another State.

In 1982, the US Congress passed a law to stop further aid to the Contras. Reagan's officials tried to illegally supply them using money from arms sales to Iran and donations from other countries, leading to the Iran–Contra Affair of 1986–87. Both sides were tired of the war, and the Sandinistas feared the Contras' unity and military success. Mediation by other regional governments led to the Sapoa ceasefire between the Sandinistas and the Contras on March 23, 1988. Later agreements aimed to bring the Contras and their supporters back into Nicaraguan society in preparation for general elections.

Center-Right Rule (1990–2006)

The FSLN lost to the National Opposition Union by 14 points in the elections on February 25, 1990. At the start of Violeta Chamorro's nearly 7 years in office, the Sandinistas still largely controlled the army, labor unions, and courts. Her government worked towards strengthening democratic systems, promoting national peace, stabilizing the economy, and selling off state-owned businesses. Because the Sandinistas still controlled the army, the United States again put sanctions on Nicaragua from 1992 to 1995. The US demanded that Nicaragua strengthen civilian control over its military and resolve claims about seized properties before lifting the sanctions.

In February 1995, Sandinista Popular Army Commander Gen. Humberto Ortega was replaced by Gen. Joaquín Cuadra, following a new military law passed in 1994. Cuadra promoted greater professionalism in the renamed Army of Nicaragua. A new police law, passed in August 1996, further established civilian control of the police and made the law enforcement agency more professional.

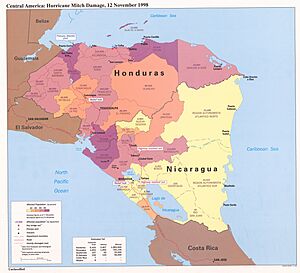

The presidential, legislative, and mayoral elections on October 20, 1996, were also judged free and fair by international observers and a national election observer group called Ética y Transparencia (Ethics and Transparency). This was despite some problems, mainly due to logistical difficulties and a very complex election law. This time, Nicaraguans elected former-Managua Mayor Arnoldo Alemán, leader of the center-right Liberal Alliance, which later became the Constitutional Liberal Party (PLC). Alemán continued to privatize the economy and support infrastructure projects like highways, bridges, and wells. This was greatly helped by foreign aid received after Hurricane Mitch hit Nicaragua in October 1998. His government faced many accusations of corruption, leading to several key officials resigning in mid-2000. Alemán himself was later found guilty of official corruption and sentenced to twenty years in jail.

In November 2000, Nicaragua held local elections. Alemán's PLC won most of the mayoral races. The FSLN did much better in larger cities, winning a significant number of capital cities, including Managua.

Presidential and legislative elections were held on November 4, 2001, the country's fourth free and fair election since 1990. Enrique Bolaños of the PLC was elected president, defeating the FSLN candidate Daniel Ortega by 14 percentage points. International observers described the elections as free, fair, and peaceful. Bolaños took office on January 10, 2002.

In November 2006, the presidential election was won by Daniel Ortega, who returned to power after 16 years in opposition. International observers, including the Carter Center, judged the election to be free and fair.

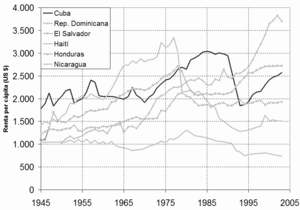

The country partly rebuilt its economy during the 1990s, but was hit hard by Hurricane Mitch at the end of October 1998, almost exactly a decade after the similarly destructive Hurricane Joan. In 2007, it was hit again by Hurricane Felix, a very strong Category 5 hurricane. Ten years later, Hurricane Nate also hit Nicaragua and destroyed much of the infrastructure in the countryside, such as communication towers.

Ortega Back in Power (2006–Present)

In the Nicaraguan general election, 2006, Daniel Ortega won about 38% of the vote in the single round, returning to power for his second term overall. The constitution at the time banned a sitting president from being immediately reelected and limited any individual to serving no more than two terms as president. Despite this, Ortega ran again and won the Nicaraguan general election, 2011 amid accusations of cheating by the losing candidate Fabio Gadea Mantilla. Economic growth during most of these two terms was strong, and tourism in Nicaragua grew especially well, partly because Nicaragua was seen as a safe country to visit.

The Nicaraguan general election, 2016 saw some opposition groups boycott the election, and there were again accusations of election fraud. There were also claims that the number of people who didn't vote was higher than what the government officially reported. The idea of a Nicaraguan Canal was a public debate and caused some disagreement. Starting April 19, 2018, criticism of the Ortega government over the canal, forest fires in the Indio Maíz nature reserve, and a planned change to the social security system led to the 2018–2022 Nicaraguan protests. The government responded to these protests with violence and harsh measures.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Nicaragua para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Nicaragua para niños

- José Antonio Lacayo de Briones y Palacios

- List of presidents of Nicaragua

- Nicaragua v. United States (1986 International Court of Justice judgment)

- Politics of Nicaragua

- Timeline of Managua

- UNAPA (1994)

General:

- History of Central America

- List of years in Nicaragua