History of books facts for kids

The history of books explores how books have changed over time. It's not just about the stories inside them, but also about the books themselves as objects. How a book was made, where it was kept, and who read it can tell us a lot about the past. Even if we don't find much about a book, that silence can also give us clues.

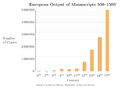

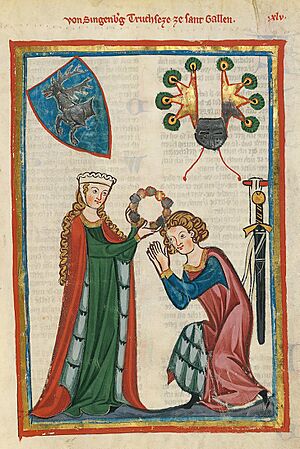

Long ago, people wrote on stone. Then they used palm leaves and papyrus. Later, parchment and paper became popular. Different ways of making books grew in places like China, the Middle East, and Europe. In the Middle Ages, people made beautiful illuminated manuscripts. These were books with amazing pictures and decorations. Before printing presses, every book was made by hand. Each one was special and unique.

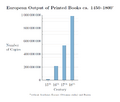

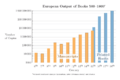

The invention of the printing press in the 1400s changed everything. It made books much faster to produce. New ideas like movable type and steam-powered presses helped even more. This led to more people learning to read. Also, rules about copyright started, protecting what authors wrote. Later, small, cheap books called chapbooks became popular.

In the 1900s, typewriters and computers changed how documents were made. Now, in the 2000s, we have e-books. You can read these on e-readers or tablets. Some people worried that physical books would disappear, but they are still very popular. Books have also become more available for everyone. Braille helps people who are visually impaired. Spoken books (audiobooks) let people listen to stories.

Contents

- How Books Began

- Books in East Asia

- Ancient American Codices

- Wax Tablets: Reusable Notes

- Parchment: Durable Writing Material

- Paper: A New Era for Books

- Books in the Middle Ages

- The Printing Press: A Revolution

- Books in Western Asia and North Africa

- Books in South Asia

- Books in the Modern Era

- Reading for the Blind

- Images for kids

- See also

How Books Began

The story of books starts with the invention of writing itself. It also includes new ideas like paper and printing. Before what we call "books" today, people used clay tablets, scrolls, and sheets of papyrus. The kind of book we know now, with pages bound together, is called a codex. At first, these were expensive, handmade manuscripts. Then came books made with printing presses. Today, some books don't even have a physical form, like e-books. Books also became easier for people with disabilities to use, thanks to Braille and audiobooks.

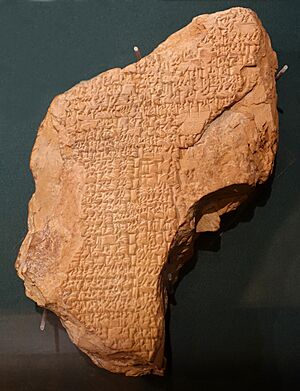

Clay Tablets: Ancient Records

People in Mesopotamia used clay tablets around 3000 BCE. They used a pointed tool called a calamus to write on wet clay. Then they dried the tablets with fire. In the ancient city of Nineveh, over 20,000 tablets from the 600s BCE were found. This was the library of the kings of Assyria. They had people who copied and took care of these clay books. This shows that books were organized even back then. Clay tablets were used in some parts of the world until the 1800s.

Cuneiform: Wedge-Shaped Writing

Writing first appeared in Sumer (modern-day Iraq) around 3000 BCE. It was used to keep records. This writing system was called cuneiform. Many clay tablets show cuneiform used for legal papers, lists of goods, and even stories. Archaeologists have found schools from 2000 BCE where students learned to write. Cuneiform means "wedge-shaped" in Latin. Scribes usually wrote on clay, but sometimes on gold. Cuneiform was used for over 3,000 years for languages like Sumerian and Akkadian.

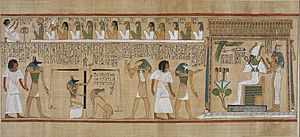

Papyrus: Ancient Egyptian Paper

Ancient Egyptians made writing material from the papyrus plant. They processed the plant stems to create sheets. The best quality papyrus was used for sacred writings. Papyrus was used in Egypt as early as 2900 BCE. Scribes used sharpened reeds or bird feathers to write. Their writing style was called hieratic, a simpler form of Egyptian hieroglyphs. Egyptians sold papyrus to other ancient cultures like Greece and Rome.

Papyrus books were long scrolls made by gluing many sheets together. Some were over 30 feet long! The text was written in columns on one side. A label on the scroll's cylinder showed the title. Many papyrus texts found in tombs were prayers and sacred writings, like the Book of the Dead. Papyrus was also used for legal documents and tax records. After the 900s CE, paper became more common. Papyrus was then often used for book covers in Egypt.

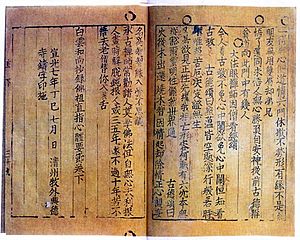

Books in East Asia

China: From Bamboo to Paper

Before paper, Chinese people wrote on bones, shells, wood, and silk. This was common long before 200 BCE. Paper was invented in China around 100 CE. China's first books were called jiance or jiandu. These were rolls of thin bamboo strips tied together with hemp, silk, or leather. The invention of paper from mulberry bark is often credited to Cai Lun.

Texts were copied using woodblock printing. This method helped spread Buddhist texts widely. The book format changed over time. It went from scrolls to folded books, and then to books bound at one edge. The first printed book still existing is the Diamond Sutra, from 868 CE. Woodblock printing was hard work. The text had to be carved into a wooden block, then used to stamp the words onto paper.

Because woodblock printing was so slow, Bi Sheng invented Movable type printing between 1041 and 1048 CE. He used individual characters made of ceramic or clay. This allowed printers to reuse the types for different texts. This idea was later invented again and improved by Johannes Gutenberg in Europe.

Japan: Reading for Everyone

In the early 1600s, very detailed books were made in Japan. For example, one person spent 60 years writing about 499 types of edible plants and animals. At first, mostly rich people could read. But soon, more schools taught children. This led to more people being able to read. Detailed writing was still common in official records and encyclopedias.

Around the 1670s, a simpler writing style appeared. It was for everyday people who were buying books for the first time. These new stories were popular with common samurai and townspeople. Books also started to include guides for different crafts. Authors had to think about their new "reading public." They learned to write in a way that everyone could understand.

Writers could now share knowledge that was once private. They wrote about local information guides. Even with more people reading, there was still some censorship in the late 1600s. The government made sure that sensitive topics like military matters or Christianity were not in public books. But overall, public reading grew, and books became popular for many different groups of people.

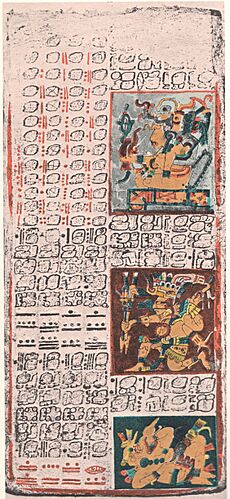

Ancient American Codices

In ancient Mesoamerica, people wrote on long strips of paper, agave fibers, or animal hides. These strips were then folded like an accordion and protected by wooden covers. These books, called codices, existed between the 200s and 700s CE. Many codices contained information about stars, religious calendars, gods, rulers' family trees, maps, and taxes. Most were kept in temples but were later destroyed by Spanish explorers.

The Maya script is the only fully understood writing system from this region. The Maya, like other Mesoamerican cultures, made accordion-style books on Amate paper. Sadly, most Maya texts were destroyed by the Spanish. One of the few surviving examples is the Dresden Codex. Other cultures had simpler writing systems in similar folded books, such as the Aztec codices.

The Florentine Codex

The Florentine Codex is a huge study from the 1500s about the Aztec people. It has over 2,000 drawings by native artists. A Spanish friar named Bernardino de Sahagun worked on it from 1545 until his death in 1590. The codex tells about Aztec culture, religion, society, economy, and nature. It is written in both Nahuatl (the Aztec language) and Spanish.

Translating the Nahuatl text into English took ten years. This translation was a very important step for understanding Aztec history. In 1979, the Mexican government published a full-color version. Since 2012, it's available online for anyone interested in Mexican and Aztec history. The Florentine Codex has 12 books and is 2,500 pages long. It covers topics like the gods, ceremonies, and other parts of Aztec life.

Wax Tablets: Reusable Notes

Romans used wooden tablets covered in wax. They could write on these pugillares with a pointed tool called a stylus and then erase it with the blunt end. These tablets were used for everyday things like accounting and notes. They were also used to teach children how to write. Several wax tablets could be joined together, looking like an early form of a codex. The word "codex" itself comes from the Latin word for a "block of wood," suggesting it came from these wooden tablets.

Parchment: Durable Writing Material

Parchment slowly replaced papyrus. Legend says King Eumenes II of Pergamon invented it, which is where its name comes from. Parchment production started around 300 BCE. It was made from animal skins (like sheep, cattle, or donkeys). Parchment lasted longer than papyrus and allowed writers to erase text. It was very expensive because the materials were rare and it took a lot of time to make. Vellum is a very fine type of parchment made from calf hide.

Scrolls in Greece and Rome

In ancient Greece and Rome, a papyrus scroll was called a "volumen." This word means "roll" or "spiral." In the 600s CE, Isidore of Seville explained that a codex is made of many books, and a book is like one scroll. He said codex comes from the word for tree trunks, because it holds many books like branches.

A scroll was rolled around two wooden sticks. You had to read it in order, from beginning to end. You couldn't easily jump to a specific part. It was like an old video cassette. Also, you needed both hands to hold the scroll, so you couldn't write while reading. The only scroll still commonly used today is the Jewish Torah.

Book Culture in Ancient Times

Authors in ancient times didn't have rights to their published works. Anyone could copy a text, or even change it. Scribes earned money, but authors mostly gained fame. A book made its author well-known. This was because authors often copied and tried to improve on older works.

Books were censored very early on. For example, the works of Protagoras were burned because he doubted the existence of gods. Cultural conflicts often led to books being destroyed. In 303 CE, the emperor Diocletian ordered Christian texts to be burned. Later, some Christians burned libraries with texts they didn't agree with. This kind of book destruction has happened throughout history, though it's less common in many nations today.

Sometimes, censorship was less obvious. Books were kept only for the elite (the rich and powerful). Books could also be used to support a political system. For example, Emperor Augustus surrounded himself with great authors. This shows how political power could control the media. Censorship, both private and public, has continued in different forms into modern times.

Libraries in Ancient Greece

We don't have much information about books in ancient Greece. Some old vases show pictures of scrolls. There wasn't a huge book trade, but there were places where books were sold. The spread of books and the care for their organization grew during the Hellenistic period. This was when big libraries were built, showing a desire for knowledge. These libraries also showed off political power.

Famous libraries included:

- The Library at Antioch.

- The Library at Athens.

- The Library at Pergamon, which had 200,000 volumes.

- The Library at Rhodes.

- The Library of Alexandria, created by Ptolemy I. It had over 500,000 volumes. All books brought into Egypt by visitors were checked and could be copied.

These libraries had workshops where scribes copied books. They also organized books, kept copies of each text, and even edited texts to create official versions. This helped spread books and knowledge.

Book Production in Rome

Book production grew in Rome in the 1st century BCE. Roman literature was influenced by Greek works. About 100,000 people in Imperial Rome could read. This meant books were mainly for literary groups. Titus Pomponius Atticus, a famous publisher, was the editor for his friend Cicero. The book business spread throughout the Roman Empire. For example, there were bookstores in Lyon. The spread of the Empire also helped spread the Latin language, which helped books reach more people.

Libraries were private or built by individuals. Julius Caesar wanted to build a library in Rome, showing that libraries were a sign of political importance. In 377 CE, Rome had 28 libraries, and many smaller ones existed in other cities. Even with many books, scientists don't have a full picture of ancient literature because thousands of books have been lost over time.

Paper: A New Era for Books

Papermaking is thought to have started in China around 105 CE. Cai Lun, an official during the Han dynasty, is credited with creating paper from mulberry bark, other plant fibers, fishnets, old rags, and hemp waste. While paper for wrapping was used earlier, paper for writing became common by the 200s CE. By the 500s, paper was even used for toilet paper in China. During the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), paper was folded into square bags to keep tea fresh. The Song dynasty (960–1279) was the first government to print paper money.

Paper came to Central Asia from China by the 700s CE. Instead of plant fibers, artisans there used rag fibers. Under Arab rule, these artisans improved their paper-making skills. They used starch to make the paper smooth. By the late 900s CE, paper had replaced papyrus as the main material for books in Islamic regions.

A big step was when paper making became mechanized. Water-powered paper mills appeared in Spain in the 1000s. This allowed for a huge increase in paper production. Paper mills grew in Italy in the late 1200s, making paper much cheaper than parchment.

Books in the Middle Ages

By the end of ancient times (between the 200s and 400s CE), the scroll was replaced by the codex. A codex is a collection of sheets joined at the back. This made it easy to quickly find a specific part of the text. You could also rest a codex on a table and take notes while reading. The codex improved with spaces between words, capital letters, and punctuation. This made silent reading possible. Tables of contents and indexes helped people find information faster. This is still the standard book form today. It's likely that early Christians helped develop the codex. Paper slowly replaced parchment. Since paper was cheaper, it helped more books be made and spread.

Books in Monasteries

Many Christian books were destroyed in 304 CE by order of Diocletian. During times of invasion, monasteries in the West kept religious texts and some ancient Greek and Roman works safe. There were also important copying centers in Byzantium.

Monasteries played a mixed role in saving books:

- They didn't just save old culture. They mainly wanted to understand religious texts using ancient knowledge. Some works were never copied if they were thought to be dangerous for monks. Also, sometimes monks scraped off old manuscripts to reuse the parchment, destroying ancient works.

- Reading was very important for monks. Many monasteries had a scriptorium. This was a workshop where monks copied and decorated manuscripts.

Copying and Saving Books

Monasteries helped save many non-religious texts. Several libraries were created, like Cassiodorus's library in Italy around 550 CE. The survival of books often depended on political and religious conflicts. These conflicts sometimes led to massive destruction of books. To protect books from thieves, librarians sometimes used chains to attach books to shelves or desks. One of the earliest chained libraries was in England in the 1500s. You might have seen chained libraries in stories like Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone.

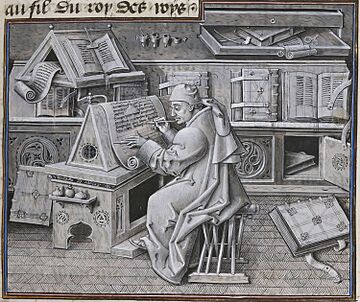

The Scriptorium: Monk Workshops

The scriptorium was the workshop for monk copyists. Here, books were copied, decorated, rebound, and stored. The armarius was in charge, acting like a librarian. Copyists helped texts travel from one monastery to another. Copying also helped monks learn texts and improve their religious education. Monks copied books for themselves and also for others who ordered them.

Copying a book had many steps: preparing the pages, laying out the design, copying the text, checking for mistakes, decorating, and binding. Making a book needed many different skills. Often, many monks worked together on one manuscript.

Changes in Book Production (1100s CE)

As cities grew in Europe, book production changed. The time when monasteries were the main book centers ended. New ways of making books grew around the first universities. Students and professors used reference books for teaching. As trade and the middle class grew, there was a demand for different kinds of books. These included books on law, history, and novels. Writing in common languages (not just Latin) also grew. Commercial scriptoria (copying workshops) became common. The job of bookseller appeared, and some even traded books internationally.

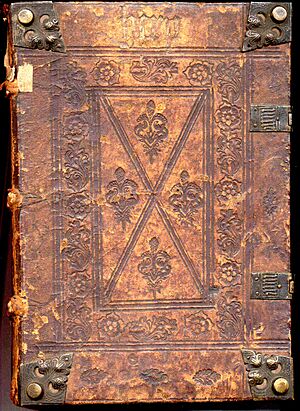

Royal libraries were also created, like those of Saint Louis and Charles V of France. Private libraries became more common in the 1300s and 1400s. Paper spread across Europe in the 1300s. It was cheaper than parchment and came from China through the Arabs in Spain. Paper was used for everyday copies, while parchment was for fancy, expensive books.

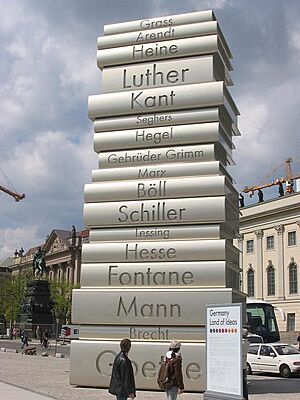

The Printing Press: A Revolution

The invention of the movable type printing press by Johannes Gutenberg and others around 1440 changed books forever. Books were no longer single objects made by hand. Publishing a book became a business. It needed money to make and a market to sell to. The cost of each book dropped a lot, which meant more books could be spread. The book we know today, in codex form and printed on paper, dates from the 1400s. Books printed before January 1, 1501, are called incunables. Printing spread quickly across Europe, but most books were still in Latin. Printing books in local languages took a bit longer.

Books in Western Asia and North Africa

Early Islamic Books

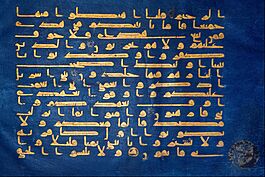

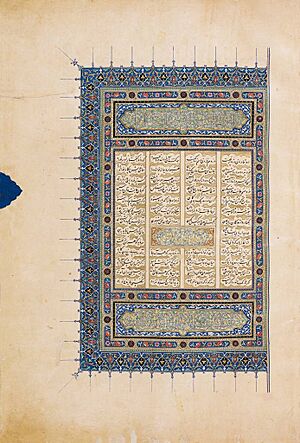

From the 600s CE, parchment was used for copying the Quran in codex form. These books ranged from large ones for public readings to small pocket-sized versions. In this period, the text was more important than pictures. Sometimes, the parchment was dyed, like the famous Blue Quran. Early Quran manuscripts were taller than they were wide, but later, the standard horizontal shape was set.

Medieval Islamic Books

The art of making books became a recognized skill in the Islamic world during the 1000s CE. This was because paper became widely available. Paper was easier to use and distribute than parchment. Also, rounded writing styles replaced older, angular ones. During this time, many types of books were made, including scientific notes, poetry, and stories, not just the Quran.

When Mongol leaders became Muslim in the 1200s CE, they supported book production. Large-scale Quran production was possible because of paper from Baghdad. More books were made, which helped spread information about the paper mills. Other artists who worked on books, like calligraphers, bookbinders, and illuminators, also benefited. Pictures started appearing in illuminated manuscripts, becoming a main part of the book. The books made by the Mongols aimed to promote religion or history.

Later Islamic Books

In the 1500s and 1600s CE, royal workshops made most manuscripts. Books were seen as status symbols or investments. Making a manuscript started with the workshop director planning the layout. Then, paper was made (sometimes with gold flecks or marbled designs). A scribe wrote the text. Finally, artists added miniature paintings, banners, and decorated frontispieces. After polishing the pages, bookbinders sewed the covers and pages together.

Baghdad became a major center for book production in the Ottoman Empire. Ottoman workshops made biographies, travel stories, and family histories. In the late 1500s, support for the arts, including books, declined due to money problems. But the arts came back under Ahmed III, who built a library at Topkapı Palace to order new manuscripts. The pictures in these books started to be influenced by European engravings. Until the late 1500s, printed books became more available, but the printing press was not fully accepted. Scribes and calligraphers worried they would lose their jobs.

The Persian Safavids greatly valued book arts. They had a strong book culture. A kitab-khana ("book house") could be a public library, a private book collection, or a workshop where calligraphers, bookbinders, and papermakers worked together. The Safavid style of manuscript pictures grew from earlier styles. The most famous Safavid manuscript is the Shahnameh, a long poem.

Printing Comes to the Middle East

Movable type for Arabic script was first made by European printing presses. In the 1530s, the first Quran was printed in Venice. The printing press was accepted by the public in the Arab and Persian worlds in the 1700s CE, even though it had been in Europe for 300 years. The first Arabic printing press was set up in Constantinople in 1720.

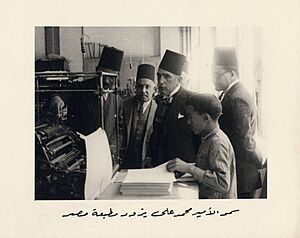

In 1815, Muhammad Ali of Egypt sent artists to Italy to learn printing. The Bulaq Press was started in Egypt in 1822. It was led by Nikula al-Masabiki, who designed the Arabic typefaces. The first book printed there was an Italian-Arabic dictionary.

Lithography (printing from stone) was introduced in the 1800s. The first Persian book printed by lithography was a copy of the Quran. It used a printing press brought from Russia to Tabriz. Lithography was good because it could easily adapt the beautiful art styles of traditional Islamic manuscripts. In Persia in the mid-1800s, some books mixed handwritten parts with printed parts.

By the late 1800s, movable type became popular again. In Egypt, most of the 10,205 books printed from 1822 to 1900 used letterpress printing. In the 1900s, arts like miniature painting and bookbinding became less popular. But calligraphy (the art of beautiful writing) is still popular.

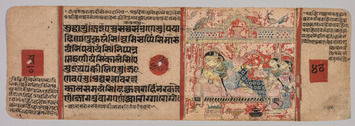

Books in South Asia

Early South Asian Manuscripts

In ancient times, people in South Asia wrote on stone slabs. The oldest surviving books are from the 900s CE and are Buddhist manuscripts. Before paper, people wrote on palm leaves, which were common in southern India. The pages were usually about three feet wide and two inches tall. Palm leaves were dried, polished, and treated to be ready for writing. The pages were tied together with a single string on the shorter side.

Paper came to the Indian Subcontinent from Egypt and Arabia in the 1000s CE. It was brought by merchants trading with Gujarat. The first papermaking mills were set up in the 1400s CE by artisans from Samarkand. However, palm leaves were still used for manuscripts in parts of eastern and southern India and Sri Lanka. Paper became common in the Jain manuscript tradition from the 1400s onwards. Paper books were thinner than palm leaf manuscripts, but they still had a horizontal layout. Pictures took up about one-third of the page, with text filling the rest.

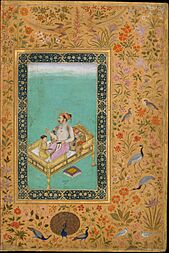

Mughal Era Books

The first Mughal Emperor, Babur, didn't support the arts much. But he wrote about his life in a book called the Baburnama. After being exiled, Babur's son Humayun brought artists who made illustrated Persian manuscripts to the Mughal court in 1540.

Even though he couldn't read or write, Mughal Emperor Akbar strongly supported book arts. He set up a painting workshop next to the royal library in Fatehpur Sikri in the late 1400s. This made producing books and illustrated manuscripts more efficient. Large, poster-sized manuscript paintings were used to help tell famous stories, like the Hamzanama. Akbar's grandson, Shah Jahan, focused more on text in manuscripts. His books also had margins filled with pictures of flowers. By Shah Jahan's time, manuscript production had slowed down. Book artists then found work in the courts of regional rulers.

In the 1600s CE, illustrated books became less popular. Single sheet artworks became more common because they were cheaper to make and buy. These single sheets were later put together into albums with decorations.

Books in the Modern Era

The Late Modern Period: Books for Everyone

The Late Modern Period saw many new types of books. Chapbooks were short, cheap books for lower-class readers. They covered many topics, from myths and fairy tales to practical advice and prayers. This helped more people learn to read. By 1890, almost everyone in Western Europe, Australia, and the USA could read. The difference in reading ability between men and women also started to disappear by 1900.

Printing presses became more mechanized. Early designs for metal and steam-powered presses appeared in the early 1800s. By the 1830s, they were widely used, especially by newspapers. Around the same time, new paper-making machines created very wide, continuous rolls of paper. The only slow part was setting the type for printing. This was solved by machines like the Linotype and Monotype. With these improvements, book production grew very quickly.

Publishing also made big advances. Authors started to get early forms of copyright protection. The Statute of Anne in 1710 gave authors basic rights to their work. Later laws gave authors more control over their books for longer periods. During the Age of Enlightenment, many more books were printed in Europe. This led to a lot of information for readers. New steam printing presses and paper mills in the early 1800s made books much cheaper and more numerous. This also changed how titles and subtitles looked. Later in the 1800s, new types of media appeared, like photography, sound recording, and film.

Contemporary Period: Digital Books

Typewriters, and then computers, made it easy for people to create and print their own documents. Desktop publishing is very common today. In the 1990s, digital multimedia became popular. This allowed texts, images, animations, and sounds to be combined easily. Hypertext made it even easier to find information. The internet also lowered the costs of making and distributing books.

E-books and the Future

It's hard to know what the future holds for books. People have always worried about books disappearing because of new media like radio, TV, and the internet. But these worries are usually too strong. Physical books have proven to be very strong and adaptable. In the 2020s, print books still sell much more than ebooks in most countries. It's still a huge industry.

Many reference materials, like encyclopedias, are now found more on the internet than in physical books. But books for fun reading are increasingly published as e-books. E-books didn't do well at first, but demand has grown a lot. This is mainly because of popular e-reader devices and more e-book titles being available. Since the Amazon Kindle came out in 2007, e-books have become very popular. Some people think they will replace paper books. E-books are easier to buy and often cheaper because there are no paper costs. E-readers are also becoming more advanced, with some supporting basic operating systems. The iPad is a good example, and even mobile phones can run e-reading apps.

Reading for the Blind

Braille is a system of reading and writing using fingertips. It was made for people who are blind or have low vision. The system has 63 characters, read from left to right. These characters are made of small raised dots, like a domino piece, representing each letter. Readers can feel the characters with two fingers. People can read Braille at about 125 words per minute, and some can reach 200 words per minute.

How Braille Was Made

Braille is named after its creator, Louis Braille, who developed it in France in 1824. Braille lost his sight at age three. He spent nine years working on an earlier system called night writing. Braille published his book "procedure for writing words, music, and plainsong in dots" in 1829. In 1854, France made Braille the official communication system for blind people. Valentin Haüy was the first person to put Braille on paper in book form. In 1932, Braille was accepted in English-speaking countries. In 1965, the Nemeth Code of Braille Mathematics and Scientific Notation was created. This code added symbols for advanced math. The system has stayed mostly the same since it was created.

Spoken Books: Audio for All

Spoken books were first created in the 1930s to help blind and visually impaired people enjoy books. In 1932, the American Foundation for the Blind made the first recordings of spoken books on vinyl records. In 1935, the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) in Britain was the first to deliver talking books on vinyl records. Each record had about 30 minutes of audio on both sides. They were played on a gramophone.

Spoken books changed to cassette tapes in the 1960s. The next step was in the 1980s with the widespread use of compact discs. CDs reached more people and made it possible to listen to books in the car. In 1995, the term audiobook became the standard for the industry. Finally, the internet made audiobooks even easier to get and carry around. Audiobooks could now be played all at once, instead of being split onto many discs.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia del libro para niños

In Spanish: Historia del libro para niños

- Book publishing by country

- Centre for the History of the Book

- Outline of books

- Textual scholarship

- Specialized databases in book history

- English Short Title Catalogue

- Early American Imprints: Series I Evans, 1639-1800

- Early English Books Online

- Incunabula Short Title Catalogue

- Universal Short Title Catalogue