Hussein of Jordan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hussein |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

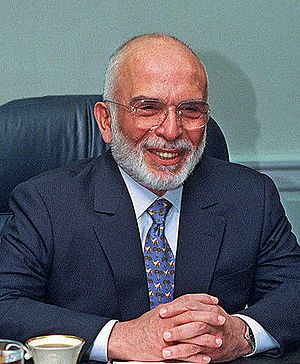

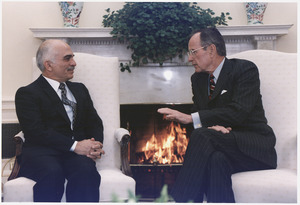

King Hussein in 1997

|

|||||

| King of Jordan | |||||

| Reign | 11 August 1952 – 7 February 1999 | ||||

| Regency ended | 2 May 1953 | ||||

| Predecessor | Talal | ||||

| Successor | Abdullah II | ||||

| Prime ministers |

See list

Fawzi Al-Mulki

Tawfik Abu Al-Huda Sa`id Al-Mufti Hazza' Majali Ibrahim Hashem Samir Al-Rifai Suleiman Nabulsi Husayn Al-Khalidi Bahjat Talhouni Wasfi Tal Hussein ibn Nasser Saad Jumaa Abdelmunim Al-Rifai Mohammad Al-Abbasi Ahmad Toukan Ahmad Lozi Zaid Al-Rifai Mudar Badran Abdelhamid Sharaf Kassim Al-Rimawi Ahmad Obeidat Zaid ibn Shaker Taher Al-Masri Abdelsalam Al-Majali Abdul Karim Al-Kabariti Fayez Tarawneh |

||||

| Born | 14 November 1935 Amman, Transjordan |

||||

| Died | 7 February 1999 (aged 63) Amman, Jordan |

||||

| Burial | 8 February 1999 Raghadan Palace |

||||

| Spouse |

|

||||

| Issue Details and adopted children |

|

||||

|

|||||

| House | Hashemite | ||||

| Father | Talal of Jordan | ||||

| Mother | Zein al-Sharaf | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| Signature |  |

||||

Hussein bin Talal (born November 14, 1935 – died February 7, 1999) was the King of Jordan from 1952 until his death in 1999. He was a member of the Hashemite family, which has ruled Jordan since 1921. King Hussein was a direct descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Hussein was born in Amman, the oldest child of Talal bin Abdullah and Zein al-Sharaf bint Jamil. His father, Talal, was the heir to King Abdullah I. Hussein started his schooling in Amman and continued his education abroad. After Talal became king in 1951, Hussein was named the next in line to the throne. The Jordanian Parliament later made Talal step down because of his illness. A group of leaders, called a regency council, ruled until Hussein was old enough. He became king at 17 years old on May 2, 1953. King Hussein was married four times and had eleven children, including the current King of Jordan, Abdullah II.

King Hussein was a constitutional monarch, meaning he ruled according to a constitution. He began his rule with a "liberal experiment," allowing a democratically elected government in 1956. However, he later ended this experiment, declared martial law, and banned political parties. Jordan fought three wars with Israel during his reign, including the 1967 Six-Day War, which resulted in Jordan losing control of the West Bank. In 1970, Hussein removed Palestinian fighters from Jordan after they threatened the country's safety. This event is known as Black September in Jordan. In 1988, he gave up Jordan's claim to the West Bank after the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was recognized as the main representative of Palestinians. He brought back elections in 1989 after protests over rising prices. In 1994, he became the second Arab leader to sign a peace treaty with Israel.

When Hussein became king in 1953, Jordan was a new country and controlled the West Bank. It had few natural resources and many Palestinian refugees from the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Hussein guided Jordan through four challenging decades of the Arab–Israeli conflict and the Cold War. He successfully balanced pressures from different groups and countries, turning Jordan into a stable, modern state. He worked hard to solve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and was seen as a peacemaker in the region. He was admired for forgiving political opponents and giving them important government jobs. Hussein survived many attempts to assassinate him and overthrow his rule. He was the longest-reigning leader in the region. He died at 63 from cancer in 1999, and his oldest son, Abdullah II, became king.

Contents

- Growing Up: King Hussein's Early Life

- Becoming King: Hussein's Accession to the Throne

- Leading Jordan: Hussein's Early Years as King

- A Time of Change: Political Shifts and Challenges

- Regional Tensions: The Arab Federation and Assassination Attempts

- Seeking Peace: Relations with Israel and Arab Neighbors

- Black September: A Conflict Within Jordan

- Working for Peace: Diplomatic Efforts and Challenges

- His Final Years: Illness, Death, and Funeral

- What He Left Behind: King Hussein's Legacy

- King Hussein's Family Life

- Military Ranks Held by King Hussein

- Books Written by King Hussein

- See also

- Images for kids

Growing Up: King Hussein's Early Life

Hussein was born in Amman on November 14, 1935. His parents were Crown Prince Talal and Princess Zein al-Sharaf. Hussein was the oldest of his siblings, who included three brothers and two sisters. Sadly, his baby sister Princess Asma died from pneumonia during a cold winter. This showed how poor his family was at the time, as they could not afford heating.

Hussein was named after his great-grandfather, Hussein bin Ali. This ancestor led the 1916 Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. Hussein belonged to the Hashemite family, which had ruled Mecca for over 700 years. They have ruled Jordan since 1921. The Hashemites are one of the oldest ruling families in the world.

The young prince started school in Amman. He then studied at Victoria College in Egypt. Later, he went to Harrow School in England. There, he became friends with his cousin Faisal II of Iraq, who was also studying at Harrow. Faisal was the King of Iraq, but he was under the care of a regent because he was the same age as Hussein.

Hussein's grandfather, King Abdullah I, was the founder of modern Jordan. He believed his own sons were not ready to be kings. So, he focused on raising his grandson Hussein. A special bond grew between them. Abdullah gave Hussein a private tutor for extra Arabic lessons. Hussein also helped his grandfather by interpreting during meetings with foreign leaders. Abdullah understood English but could not speak it well.

On July 20, 1951, 15-year-old Prince Hussein went to Jerusalem. He was there to pray at the Masjid Al-Aqsa with his grandfather. An assassin shot at Abdullah and Hussein. There were rumors that the King was planning a peace treaty with the new state of Israel. King Abdullah died, but Hussein survived. Witnesses said he chased the assassin. Hussein was also shot, but a medal on his uniform, given to him by his grandfather, stopped the bullet.

Becoming King: Hussein's Accession to the Throne

After King Abdullah I's death, his oldest son, Talal, became King of Jordan. Talal named his son Hussein as the next in line to the throne on September 9, 1951. King Talal ruled for less than 13 months. The Parliament then asked him to step down because of his mental health. Doctors had diagnosed him with schizophrenia. During his short rule, Talal introduced a modern and somewhat liberal constitution in 1952. This constitution is still used today.

Hussein was declared king on August 11, 1952, three months before his 17th birthday. He was staying with his mother in Switzerland when a telegram arrived. It was addressed to 'His Majesty King Hussein'. Hussein later wrote that he knew his school days were over without even opening it. He returned home to cheering crowds.

A council of three men was appointed to rule until Hussein turned 18 (by the Muslim calendar). This council included the prime minister and the heads of the Senate and House of Representatives. Meanwhile, Hussein continued his studies at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. He officially became king on May 2, 1953. This was the same day his cousin Faisal II also became the full king of Iraq.

Leading Jordan: Hussein's Early Years as King

When Hussein became king, Jordan controlled the West Bank. This area was captured by Jordan during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and added to Jordan in 1950. Jordan had few natural resources. It also had many Palestinian refugees from the war. Palestinians made up two-thirds of the population after the West Bank was added.

Hussein appointed Fawzi Mulki as prime minister. Mulki's policies allowed more freedom for the press. But this led to unrest as opposition groups spoke out against the monarchy. Palestinian fighters, called "fedayeen," used Jordanian land to attack Israel. This sometimes led to strong responses from Israel. One such event was the Qibya massacre in 1953. Israeli forces attacked the West Bank village of Qibya, killing 66 civilians. This caused protests, and Hussein dismissed Mulki in 1954.

Jordan faced tensions during the Cold War. The 1955 Baghdad Pact was an effort by Western countries to form an alliance against Soviet influence. Jordan was pressured to join. However, Gamal Abdel Nasser's ideas of Pan-Arabism were popular in the Arab world. Joining the pact caused large riots in Jordan. Hussein realized that Arab nationalism was very strong. So, he decided to reduce Jordan's ties with Britain.

On March 1, 1956, Hussein showed Jordan's independence. He removed Glubb Pasha as the commander of the Arab Legion. He replaced all senior British officers with Jordanians. The army was renamed the "Jordan Armed Forces-Arab Army." He also ended the treaty with Britain and replaced British financial help with aid from other Arab countries. These bold decisions made Hussein popular in Jordan and improved relations with other Arab states.

A Time of Change: Political Shifts and Challenges

In 1956, Hussein allowed a new parliamentary election. The National Socialist Party won the most seats. Hussein asked their leader, Suleiman Nabulsi, to form a government. This was the only democratically elected government in Jordan's history. Hussein called it a "liberal experiment."

However, disagreements soon arose between the King and Nabulsi's government. Nabulsi wanted Jordan to be closer to Nasser's Egypt. But Hussein wanted Jordan to remain allied with Western countries. In March 1957, Nabulsi wanted to dismiss many senior army officers. Hussein initially agreed, but then refused a longer list. Nabulsi's government had to resign on April 10.

On April 13, riots broke out in the Zarqa army barracks. Hussein, then 21, went to stop the fighting between loyalist and Arab nationalist army units. Rumors had spread that the King was killed. A Syrian force began moving towards the Jordanian border, thinking it was a coup attempt. But they turned back when the Jordanian army showed loyalty to Hussein. Hussein then declared martial law. This limited some freedoms, but he later eased some of these rules.

Regional Tensions: The Arab Federation and Assassination Attempts

The 1950s saw a "Cold War" among Arab states. Egypt, led by Nasser, and Syria formed the United Arab Republic (UAR) in February 1958. To balance this, Hussein and his cousin, King Faisal II of Iraq, created the Arab Federation in February 1958. These two groups then started a propaganda war against each other.

In July 1958, there was a plot to overthrow both Hashemite monarchies. Iraqi conspirators attacked the royal palace in Iraq. They killed all members of the Iraqi royal family, including King Faisal II. Hussein was devastated. He ordered a Jordanian force to reclaim the Iraqi throne, but it was called back. Worried about a similar coup in Jordan, Hussein made martial law stricter. American troops arrived in Jordan to support pro-Western governments.

In November 1958, Hussein was flying his own plane over Syria. Two Syrian jets tried to attack him. Hussein skillfully avoided them and landed safely in Amman. He received a hero's welcome. Even Israeli politician Golda Meir was reported to say that Israelis prayed for King Hussein's safety. Israelis preferred Hussein to stay in power rather than a Nasser-supported government.

Hussein faced several assassination attempts. One plot involved replacing his nose drops with strong acid. Another was discovered when many cats died in the royal palace. It turned out the cook was testing poisons to use against the King. Hussein later pardoned the cook. These attempts stopped after a coup in Syria in 1961 caused the UAR to break apart. Hussein then focused on building Jordan.

Seeking Peace: Relations with Israel and Arab Neighbors

Secret talks between Jordan and Israel began in the early 1960s. Hussein had a Jewish doctor who helped him communicate with Israeli leaders. Hussein emphasized his commitment to finding a peaceful solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

In 1964, Hussein also improved relations with Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. This made Hussein more popular in Jordan and the Arab world. During an Arab League summit in Cairo, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was formed. Jordan agreed to join the United Arab Command. The PLO saw itself as the voice of Palestinians, which sometimes conflicted with Jordan's control over the West Bank.

The Samu Incident and Six-Day War

Palestinian groups like Fatah began launching attacks against Israel from Jordan in 1965. This often led to Israeli counter-attacks on Jordan. One major event was the Samu Incident in November 1966. Israel attacked the Jordanian-controlled West Bank town of As-Samu after three Israeli soldiers were killed. This attack caused many Arab casualties. It made Hussein very unpopular in Jordan, as people felt he had been betrayed by Israel.

The events at Samu led to large protests in the West Bank. People accused Hussein of not being able to defend them. They chanted pro-Nasser slogans. On May 30, 1967, Hussein quickly signed a mutual defense treaty with Egypt. He returned home to cheering crowds.

On June 5, 1967, the Six-Day War began. Israel launched a surprise attack that destroyed Egypt's Air Force. Based on wrong information from Cairo, the Egyptian commander in Jordan ordered the Jordanian army to attack Israeli targets. Jordanian planes were destroyed when they went to refuel. Israel's air superiority was key.

By June 7, Jordanian forces had to withdraw from the West Bank. Jerusalem's Old City and the Dome of the Rock were lost after fierce fighting. Jordan suffered a huge loss with the West Bank, which contributed 40% to its economy. About 200,000 Palestinian refugees fled to Jordan. By June 11, Israel had won the war, capturing the West Bank from Jordan, Gaza and the Sinai from Egypt, and the Golan Heights from Syria.

After the war, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 242. This resolution called for Israel to withdraw from the lands it occupied in 1967. Hussein restarted talks with Israeli representatives, but they did not make progress.

Black September: A Conflict Within Jordan

After Jordan lost the West Bank in 1967, Palestinian fighters, or "fedayeen," moved their bases to Jordan. They increased their attacks on Israel. In March 1968, Israel attacked a PLO camp in Karameh, a Jordanian town. This turned into a full battle. The perceived joint Jordanian-Palestinian victory in the Battle of Karameh led to more support for Palestinian fighters in Jordan.

The PLO grew stronger in Jordan. By early 1970, fedayeen groups openly called for the overthrow of the Hashemite monarchy. They acted like a "state within a state," ignoring local laws. They even tried to assassinate King Hussein twice. This led to violent clashes between them and the Jordanian army.

The situation reached a peak with the Dawson's Field hijackings on September 10, 1970. Fedayeen hijacked three civilian planes and landed them in Zarqa. They took foreign people hostage and later blew up the planes in front of the international press. Hussein saw this as the final straw. He ordered the army to act.

On September 17, the Jordanian army surrounded cities with a PLO presence, like Amman and Irbid. They began shelling the fedayeen, who were in Palestinian refugee camps. A force from Syria with PLO markings advanced towards Irbid, which the fedayeen declared a "liberated" city. On September 22, the Syrians withdrew after the Jordanian army launched an air and ground attack. An agreement between PLO leader Yasser Arafat and Hussein ended the fighting on September 27.

Jordan allowed the fedayeen to leave for Lebanon. This event later contributed to the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. The Black September Organization was founded that year, named after the conflict. This group was responsible for assassinating Jordanian prime minister Wasfi Tal in 1971. They also carried out the 1972 Munich massacre against Israeli athletes.

In 1972, Hussein proposed his "United Arab Kingdom" plan. This plan suggested two self-governing areas on each side of the Jordan River. The military and foreign affairs would be handled by a central government in Amman. This plan depended on a peace agreement between Israel and Jordan. However, Israel, the PLO, and other Arab states rejected it.

The Yom Kippur War and PLO Recognition

After the 1967 war, peace talks between Arab countries and Israel stalled. This led to fears of another war. Hussein secretly met with Israeli prime minister Golda Meir in September 1973. He discussed what both sides already knew: that the Syrian army was on alert.

Egypt and Syria launched the Yom Kippur War against Israel on October 6, 1973, without Hussein's full knowledge. On October 13, Jordan joined the war. It sent troops to help the Syrians in the Golan Heights. Later peace talks with Israel failed. Jordan wanted Israel to completely withdraw from the West Bank. Israel preferred to keep control but with Jordanian administration.

At the 1974 Arab League summit in Morocco, Arab countries recognized the PLO as "the sole representative of the Palestinian people." This was a diplomatic setback for Hussein. Later, Hussein supported Iraqi President Saddam Hussein during the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988). Saddam provided Jordan with cheap oil, and Jordan allowed Iraq to use its Port of Aqaba for trade.

Working for Peace: Diplomatic Efforts and Challenges

After the PLO moved from Jordan to Lebanon in 1970, there were many attacks between the PLO and Israel in southern Lebanon. Israel launched major attacks into Lebanon in 1978 and 1982. The 1982 conflict worried Hussein, as Israeli forces surrounded Beirut. The PLO was to be expelled from Lebanon. Some suggested they move to Jordan, but PLO leader Arafat rejected this. The fedayeen were instead moved to Tunisia.

In 1983, American president Ronald Reagan proposed a peace plan similar to Hussein's 1972 federation plan. Hussein and Arafat agreed to it, but the PLO's executive office rejected it. Later, Hussein and Arafat signed a Jordan–PLO agreement for a peaceful solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This was a big step for the PLO. However, Israel and major world powers did not support it. Talks between the PLO and Jordan eventually failed. Hussein announced that Jordan could not continue to work with the PLO leadership.

Jordan then started to crack down on the PLO. It closed their offices in Amman. Jordan also announced a large development plan for the West Bank. This was to improve its image there, at the expense of the PLO.

Disengagement from the West Bank

On December 9, 1987, an Israeli truck driver hit four Palestinians in a Gaza refugee camp. This sparked unrest that spread to the West Bank. This uprising, called the Intifada, aimed for Palestinian independence from Israeli occupation. It also increased support for the PLO and reduced Jordan's influence in the West Bank.

Jordanian leaders began to think that Jordan might be better off without the Palestinians and the West Bank. On July 1, 1988, the Jordanian Ministry of Occupied Territories Affairs was closed. On July 28, Jordan ended its West Bank development plan. Two days later, a royal order dissolved the House of Representatives. This removed West Bank representation in Parliament.

In a televised speech on August 1, Hussein announced the "severing of Jordan's legal and administrative ties with the West Bank." This meant Jordan gave up its claim to the West Bank. It also took away Jordanian citizenship from Palestinians in the West Bank. However, Jordan kept its special role in protecting Muslim and Christian holy sites in Jerusalem. Israeli politicians were surprised. They later realized this was a real shift in Jordan's policy. In November 1988, the PLO accepted all United Nations resolutions and agreed to recognize Israel.

Economic Challenges and Return to Democracy

Jordan's decision to separate from the West Bank slowed its economy. The Jordanian dinar lost a third of its value in 1988. Jordan's foreign debt became twice its gross national product (GNP). Jordan had to introduce strict economic measures. On April 16, 1989, the government increased prices for gasoline, fees, and cigarettes. This was to raise money as part of an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

On April 18, riots began in Ma'an and spread to other southern towns. Protesters clashed with the police. Six protesters and two policemen were killed. The protests, though sparked by economic issues, became political. People accused the government of corruption. They demanded that martial law, in place since 1957, be lifted. They also wanted parliamentary elections to resume. The last election was in 1967.

Hussein agreed to the demands. He dismissed the prime minister and appointed Zaid ibn Shaker. In May 1989, Hussein announced a royal commission to create a reform document called the National Charter. This charter aimed to set a timeline for democratic changes. Parliamentary elections were held on November 8, 1989, the first in 22 years. The National Charter was approved by parliament in 1991.

The Gulf War and Peace with Israel

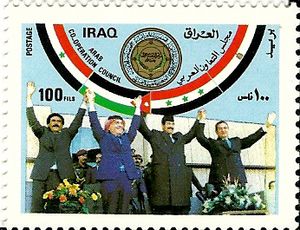

In July 1988, the Iran-Iraq war ended. Hussein had advised Saddam to improve his image in the West. Iraq and Jordan formed the Arab Cooperation Council (ACC) in February 1989, along with Egypt and Yemen.

Saddam's invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990, led to the Gulf War. Hussein was surprised by the invasion. He was the ACC chairman and a personal friend of Saddam. Hussein tried to mediate, but his efforts were undermined when Egypt condemned Iraq. Kuwait and Saudi Arabia became suspicious of Hussein.

On August 6, American troops arrived at the Kuwait-Saudi Arabian border. Saddam annexed Kuwait on August 8. Jordan, like the rest of the world, did not recognize this. The United States saw Jordan's neutrality as siding with Saddam. They cut aid to Jordan, which Jordan relied on. Gulf countries also stopped their aid. Hussein's standing in the world was severely affected.

Jordan's public opinion was against international intervention. Hussein's popularity among Jordanians grew. He visited many countries to promote a peaceful solution. He warned Saddam to withdraw his forces, or they would be forced out. Saddam refused but agreed to release Western hostages. Jordan sent troops to its borders with Iraq and Israel. Jordan also faced the arrival of 400,000 Palestinian refugees from Kuwait. By February 28, 1991, Iraqi forces were removed from Kuwait.

Jordan participated in economic sanctions against Iraq, even though it hurt its own economy. The end of the Gulf War and the Cold War allowed the United States to play a bigger role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Hussein agreed to join an international peace conference to repair Jordan's relationship with the U.S.

Hussein formed a joint Palestinian-Jordanian delegation for the Madrid Peace Conference in October 1991. The conference aimed to set a framework for negotiations. The PLO suggested a Palestinian state in a confederation with Jordan. Meanwhile, the Muslim Brotherhood, Jordan's main opposition, opposed peace talks with Israel.

Hussein had health problems and could not participate in all the talks. He had his left kidney removed due to precancerous cells. When he returned to Jordan, he received a hero's welcome. In 1993, the Oslo Accords were signed between Arafat and Rabin in secret, without Hussein's knowledge. This largely sidelined Jordan.

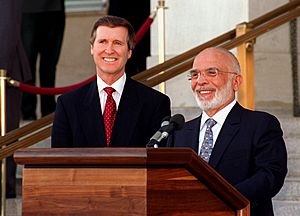

On July 25, 1994, Rabin and Hussein signed the Washington declaration. This announced the "end of the state of belligerency." This led to the Israel–Jordan peace treaty, signed on October 26. The treaty was the result of over 58 secret meetings between Hussein and Israeli leaders over 31 years. It recognized Jordan's role in Jerusalem's holy sites, which angered Arafat. Jordan's relations with the United States greatly improved. The U.S. forgave $700 million of Jordan's debt and provided substantial aid.

On November 4, 1995, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated. Hussein attended Rabin's funeral in Jerusalem. This was his first time in Jerusalem since the 1967 war. Hussein compared Rabin's death to his grandfather's assassination in 1951. He vowed to continue the legacy of peace.

Syrian President Hafez Al-Assad was unhappy with Jordan's peace treaty with Israel. The CIA warned Hussein of Syrian plots to assassinate him and his brother. Later, the CIA also warned of Iraqi plots to attack Western targets in Jordan.

Tensions with Israel

Hussein's support for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu soon backfired. Israel's actions, like building settlements in East Jerusalem and clashes at the Temple Mount, caused strong criticism in the Arab world. On March 9, 1997, Hussein sent Netanyahu a letter expressing his deep disappointment.

Four days later, on March 13, a Jordanian soldier killed seven Israeli schoolgirls near the Island of Peace. Hussein immediately returned from Spain. He traveled to the Israeli town of Beit Shemesh to offer his condolences to the grieving families. He knelt before them, saying the incident was "a crime that is a shame for all of us." He also sent the families $1 million as compensation. The soldier was found to be mentally unstable.

On September 27, 1997, eight Mossad agents tried to assassinate Jordanian citizen Khaled Mashal, head of the Palestinian group Hamas, in Jordan. Two agents were caught by Mashal's bodyguard. Hussein was furious. Jordanian authorities demanded an antidote to save Mashal's life, but Netanyahu refused. Jordan threatened to storm the Israeli embassy to capture the other agents. Hussein called American President Clinton, threatening to cancel the peace treaty if Israel did not provide the antidote. Clinton intervened, and Israel revealed the antidote. Khaled Mashal recovered. Jordan's relations with Israel worsened. The Mossad agents were released after Israel agreed to free 23 Jordanian and 50 Palestinian prisoners.

Mounting opposition in Jordan to the peace treaty led Hussein to restrict freedom of speech. Some critics were imprisoned. However, Hussein later personally drove his fiercest critic, Laith Shubeilat, home from prison. In 1998, Jordan refused a secret request from Netanyahu to attack Iraq using Jordanian airspace.

His Final Years: Illness, Death, and Funeral

In May 1998, Hussein, a heavy smoker, was admitted to the Mayo Clinic. Doctors later diagnosed him with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a type of cancer. He stayed at the clinic for several months, receiving chemotherapy. His brother Hassan acted as regent during this time. Hussein earned the respect of the Mayo Clinic staff for his kindness.

In October 1998, while undergoing treatment, Hussein attended the Wye Plantation talks between Israeli and Palestinian delegations. Looking weak, he urged both Arafat and Netanyahu to overcome their differences. His presence encouraged them to reach an agreement. Hussein received a standing ovation and praise from President Clinton.

In Jordan, 1998 was a difficult year economically. There was also a government scandal involving contaminated water. The head of intelligence, Samih Batikhi, visited Hussein at the Mayo Clinic. He spoke against Hussein's brother Hassan and supported Hussein's oldest son, Abdullah, as the next king. Abdullah, then 36, had strong support from the army.

On his way back to Jordan in January 1999, Hussein stopped in London. Doctors advised him to rest, but he returned to Jordan. He announced he was "completely cured." However, he publicly criticized his brother Hassan's handling of internal affairs. On January 24, 1999, Hussein replaced Hassan with his son Abdullah as the next in line to the throne. Hassan accepted the decision gracefully.

On January 25, the day after naming Abdullah as crown prince, Hussein returned to the United States. He was experiencing fevers, a sign that his cancer had returned. On February 2, he received a bone marrow transplant, which failed. His organs began to fail. On February 4, at his request, he was flown back to Jordan in a coma. Fighter jets from several countries escorted his plane.

Hussein arrived at the King Hussein Medical Center in Amman. Thousands of Jordanians gathered outside, despite heavy rain. They chanted his name, wept, and held his pictures. At 11:43 AM on February 7, Hussein was pronounced dead.

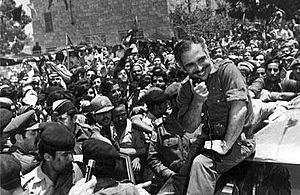

Hussein's flag-draped coffin was carried in a 90-minute procession through Amman. An estimated 800,000 Jordanians braved the cold to say goodbye. Riot police were present to manage the crowds.

The UN General Assembly held a special session to honor King Hussein. His funeral was held at the Raghadan Palace. It was the largest gathering of foreign leaders since 1995. Syrian President Hafez Al-Assad and Israeli statesmen were in the same room for the first time. Four American presidents were also present. Bill Clinton said he had never seen such a great outpouring of the world's appreciation for a human being. Hussein was succeeded by his oldest son, Abdullah II.

What He Left Behind: King Hussein's Legacy

Historians believe the assassination of Hussein's grandfather, King Abdullah I, was a key event in Hussein's life. He was only 15 when he witnessed it. Two years later, at 17, he became king. He inherited a young kingdom whose neighbors questioned its right to exist. Jordan had few natural resources and many Palestinian refugees. From a young age, he had to take on huge responsibilities. Despite Jordan's small size, he managed to give it significant political influence globally.

Hussein saw the Palestinian issue as the most important national security matter. He believed the only way to solve the conflict was through peaceful means. His decision to join the 1967 war cost him half his kingdom. After the war, he became a strong supporter of a Palestinian state. His 58 secret meetings with Israeli representatives led to the Israel–Jordan peace treaty in 1994. He considered this his "crowning achievement."

Hussein was known for including his opponents in government. He was the longest-reigning leader in the region. He survived many assassination attempts and plots to overthrow him. He was known to pardon political opponents, even those who tried to kill him. He sometimes gave them important government jobs. He was described as a "benign authoritarian" leader.

During his 46-year rule, Hussein was seen as a brave and humble leader. Jordanians called him the "builder king." He transformed Jordan from a divided, less developed country into a stable, modern state. By 1999, 90% of Jordanians had been born during his reign.

From the start, Hussein focused on building Jordan's economy and industries. He wanted to improve the standard of living. In the 1960s, Jordan's main industries, like phosphate and cement, grew. The first network of highways was built. Social improvements during his reign were significant. In 1950, only 10% of Jordanians had access to water, sanitation, and electricity. By the end of his rule, this reached 99% of the population. In 1960, only 33% of Jordanians could read and write. By 1996, this number climbed to 85.5%. Infant mortality rates also dropped significantly.

Hussein established the Al-Amal medical center in 1997, specializing in cancer treatment. In 2002, it was renamed the King Hussein Cancer Center in his honor. It is now a leading medical facility in the region.

Challenges and Criticisms

King Hussein was not very interested in the details of the economy. He was called the "fundraiser-in-chief" because he constantly sought foreign aid. Jordan became very dependent on aid from different countries.

He was also seen as too soft on some ministers accused of corruption. The peace treaty with Israel in 1994 led to strong opposition in Jordan. Critics focused their anger on the King. In response, Hussein limited freedom of speech. He also changed the parliamentary election law. This new system aimed to increase the representation of independent, loyal candidates and tribal groups. It reduced the influence of Islamist and other political parties. These actions slowed Jordan's path toward democracy.

In 1977, a newspaper reported that King Hussein received money from the CIA for 20 years. This money was used to establish an intelligence service. However, it was criticized for not being overseen by the government.

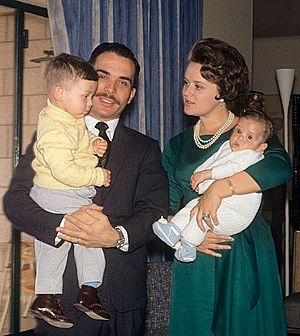

King Hussein's Family Life

King Hussein married four times and had eleven children:

- Sharifa Dina bint Abdul-Hamid (1929–2019), married on April 19, 1955. She was a distant cousin of King Hussein's father and a university lecturer. They divorced in 1957.

- Princess Alia bint Hussein (born in 1956). She has three sons.

- Antoinette Gardiner (born in 1941), married on May 25, 1961. She was a British army officer's daughter. They divorced in 1972.

- Abdullah II (born in 1962). He is the current King of Jordan. He is married to Rania Al-Yassin and they have four children.

- Prince Faisal bin Hussein (born in 1963). He is a Lieutenant-General and former Commander of the Royal Jordanian Air Force. He has six children from three marriages.

- Princess Aisha bint Hussein (born in 1968, Zein's twin). She is a Brigadier-General in the Jordanian Armed Forces. She has two children.

- Princess Zein bint Hussein (born in 1968, Aisha's twin). She has two children and an adopted daughter.

- Alia Bahauddin Toukan, Queen Alia Al-Hussein (1948–1977), married on December 24, 1972. Jordan's international airport is named after her. She died in a helicopter crash in 1977.

- Princess Haya bint Hussein (born in 1974). She has two children.

- Prince Ali bin Hussein (born in 1975). He has two children.

- Abir Muhaisen, (born in 1972, adopted by the couple in 1976).

- Lisa Najeeb Halaby (born in 1951), married on June 15, 1978. She was an Arab-American.

- Hamzah bin Hussein (born in 1980). He has six children from two marriages.

- Prince Hashim bin Hussein (born in 1981). He has five children.

- Princess Iman bint Hussein (born in 1983). She has one son.

- Princess Raiyah bint Hussein (born in 1986).

Hussein was a very enthusiastic ham radio operator. He was an Honorary Member of The Radio Society of Harrow. He was popular in the amateur radio community and asked others to call him without his royal title. His call sign was JY1. This inspired the name for Jordan's first satellite, the JY1-SAT, launched in 2018.

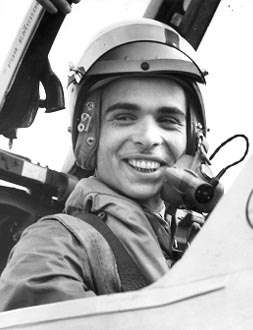

Hussein was also a trained pilot. He enjoyed flying both airplanes and helicopters as a hobby. He was also a big fan of motorcycles. The cover of Queen Noor's book Leap of Faith: Memoirs of an Unexpected Life shows the King and Queen riding a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. The King also loved race-car driving, water sports, skiing, and tennis.

Military Ranks Held by King Hussein

King Hussein I bin Talal I held these ranks:

Jordan:

Jordan:

Admiral of the Fleet, Royal Jordanian Navy.

Admiral of the Fleet, Royal Jordanian Navy. Field Marshal, Royal Jordanian Army.

Field Marshal, Royal Jordanian Army. Marshal of the Air Force, Royal Jordanian Air Force.

Marshal of the Air Force, Royal Jordanian Air Force.

Egypt:

Egypt:

Honorary Field Marshal of the Egyptian Army – February 21, 1955.

Honorary Field Marshal of the Egyptian Army – February 21, 1955.

United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

Honorary Air Chief Marshal of the Royal Air Force – July 19, 1966.

Honorary Air Chief Marshal of the Royal Air Force – July 19, 1966.

Books Written by King Hussein

- Hussein of Jordan (1962). Uneasy Lies the Head. B. Geis Associates. https://books.google.com/books?id=DgRuAAAAMAAJ.

- Hussein of Jordan (1969). My War with Israel. Morrow. https://books.google.com/books?id=zZRtAAAAMAAJ.

See also

In Spanish: Huséin I de Jordania para niños

In Spanish: Huséin I de Jordania para niños

- King Abdullah II

- Hashemites

- List of kings of Jordan

- List of things named after King Hussein

- List of covers of Time magazine (1960s)

Images for kids