Monarchy of Canada and the Indigenous peoples of Canada facts for kids

The connection between the Canadian Crown and Indigenous peoples in Canada is a long one. It goes back to the very first meetings between Indigenous peoples and European settlers. Over hundreds of years, special agreements called treaties were made between the monarch and Indigenous nations.

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in Canada have a unique relationship with the King or Queen. Like the Māori in New Zealand and their Treaty of Waitangi, many Indigenous peoples see this connection as being with the lasting Crown of Canada. They do not see it as being with the changing government. These agreements are managed by Canadian Aboriginal law. The Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs oversees them.

Contents

Understanding the Relationship with the Crown

The bond between Indigenous peoples in Canada and the Canadian Crown is based on both laws and old traditions. Indigenous peoples see the treaties as legal contracts. They also see them as promises made by kings and queens to always protect their well-being. These promises also define their rights. They help balance Indigenous self-rule with the monarch's rule in Canada.

Agreements are made with the Crown because the monarchy is seen as stable and continuous. This is different from political governments, which can change often. The idea is that the link between the monarch and Indigenous peoples will last "as long as the sun shines, grass grows and rivers flow."

This relationship is often described as a partnership. It is seen as "special" and like a "kinship," almost like family. Experts in law have noted that First Nations often "strongly support the monarchy."

What is the Crown's Role?

Treaties were signed between European monarchs and First Nations in North America as early as 1676. Only those in Canada survived the American Revolution. These Canadian treaties date back to the early 1700s.

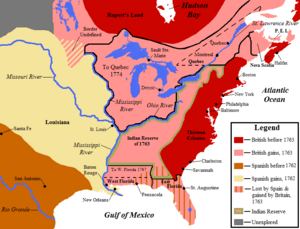

Today, a key guide for relations is King George III's Royal Proclamation of 1763. While not a treaty, First Nations see it as their "Indian Bill of Rights." It applies to both the British and Canadian Crowns. This document is still part of the Canadian constitution.

The proclamation set aside some lands for colonists. It reserved other lands for First Nations. This confirmed Indigenous ownership of their lands. It also made it clear that Indigenous groups were self-governing. They had a "nation-to-nation" relationship with non-Indigenous governments. The monarch acted as a go-between.

This created a special bond where the Crown is responsible for certain guarantees to First Nations. This means the "honour of the Crown" is very important in dealings with Indigenous leaders.

How the Relationship is Shown

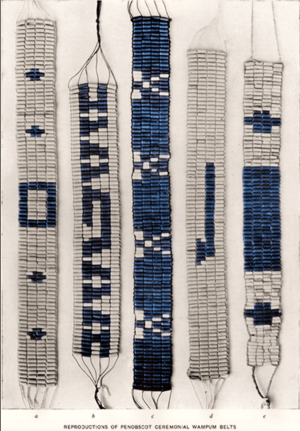

The connection between the Crown and Indigenous peoples is often shown through special events. These include pow-wows or ceremonies. They might celebrate a treaty anniversary. Sometimes, the monarch or another member of the Canadian Royal Family takes part. Or, a ceremony might happen when a royal family member is on a tour of Canada. Indigenous peoples have always been part of these royal tours.

Gifts are often exchanged. Titles have also been given to royal figures. For example, the Ojibwa called King George III the Great Father. Queen Victoria was later called the Great White Mother. Queen Elizabeth II was named Mother of all People by the Salish nation in 1959. Her son, Prince Charles, was given the title Attaniout Ikeneego by the Inuit in 1976. This means Son of the Big Boss.

Since 1710, Indigenous leaders have met with Royal Family members to discuss treaty matters. Many still use their connection to the Crown to achieve their goals. These public events have been used to present complaints to the Monarch. Indigenous people in Canada value being able to do this in front of national and international cameras.

History of the Crown's Connections

Early Days: French and British Crowns

Explorers sent by French and English monarchs first met Indigenous peoples in North America in the late 1400s and early 1500s. These meetings were usually peaceful. Each side wanted allies to gain land from the other. Partnerships were often made through treaties. The first was signed in 1676.

The English also used friendly gestures to build ties with Indigenous peoples. The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), founded in 1670, spread westward. Its traders introduced the idea of a fair monarch. This helped inspire loyalty and peaceful relations. During the fur trade, marriages between traders and Indigenous women also formed alliances. When permanent settlement was planned, treaties became the main way of relating.

The Great Peace of Montreal was signed in 1701. It involved the Governor of New France, representing King Louis XIV, and 39 First Nations chiefs. In 1710, Indigenous leaders visited the British monarch in person. Queen Anne met with four chiefs, called the Four Mohawk Kings, in London. They were treated like diplomats. They asked for military help against the French and for missionaries. Queen Anne helped with their requests.

Land and Treaties

Both British and French monarchs believed they owned all the land in North America. This included lands where First Nations lived. Treaties usually set boundaries between land for settlers and land for Indigenous peoples. French kings gave Indigenous peoples reserves for their exclusive use. For example, land north and west of the Saint Lawrence River was called "Indian country." It was forbidden for settlement without the King's permission.

British kings did the same. The Friendship Treaty of 1725, which ended Dummer's War, created a relationship between King George I and Indigenous tribes. It promised that Indigenous people would "not be molested" by the King's subjects. The British claimed this treaty gave them title to Nova Scotia and Acadia. The Mi'kmaq later made peace with the British by signing the Halifax Treaties.

Impact of Colonization

The settlement of land by Europeans led to the colonization of Indigenous lands, people, and cultures. This history still affects Canadian government policies toward Indigenous peoples. For example, the Indian Act once prevented Indigenous women from keeping their status. This was changed in 1985.

Monarchs also sought alliances with First Nations. The Iroquois sided with Kings George II and III. The Algonquin sided with Kings Louis XIV and XV. When French territories were given to George III in 1760, questions arose about how Indigenous peoples there would be treated. A treaty signed in Montreal in 1760 suggested that First Nations allied with the French King would become subjects of King George.

In 1763, George III issued a Royal Proclamation. It recognized First Nations as self-governing groups. It also confirmed their land rights. This became the main document guiding the relationship between the monarch and Indigenous peoples in North America.

However, as constitutional monarchy developed, the King's powers became limited. Ministers, accountable to parliament, began using the sovereign's powers. This change happened without consulting First Nations.

After the American Revolution

During the American Revolution, First Nations helped King George III's forces. But the British lost the war. The Treaty of Paris (1783) divided British North America into the United States and the remaining British Canadas. This created a new border through some Indigenous lands. Some Indigenous nations felt betrayed by the King. New treaties were made. Indigenous nations who lost land in the United States were given new land in Canada by the King.

The Mohawk Nation was one such group. They left their lands in present-day New York State. As compensation, George III promised land in Canada to the Six Nations. In 1784, some Mohawks settled in what is now the Bay of Quinte and the Grand River Valley. Two of North America's only three Chapels Royal were built there. These chapels, Christ Church Royal Chapel of the Mohawks and Her Majesty's Chapel of the Mohawks, symbolize the connection between the Mohawk people and the Crown.

Treaties with Indigenous peoples across southern Ontario were called the Covenant Chain. They protected First Nations' rights. This encouraged loyalty to the sovereign. As allies of the King, they helped defend his North American lands, especially during the War of 1812.

In 1860, during a royal tour, First Nations showed their loyalty to Queen Victoria. They also raised concerns about the Indian Department to the Queen's son, Prince Albert Edward. In the same year, Nahnebahwequay of the Ojibwa met with the Queen. When the Marquess of Lorne and his wife, Princess Louise, visited British Columbia in 1882, Indigenous peoples welcomed them with songs and ceremonies.

In 1870, Britain transferred Rupert's Land to Canada. More treaties were signed between 1871 and 1921. The Crown arranged land exchanges. Indigenous groups received reserves and other support like livestock, education, and health care. However, these treaties did not always ensure peace. The North-West Rebellion of 1885 was sparked by concerns from Métis people and Cree about unfair treaties.

Canada's Independence and the Crown

After Canada became legislatively independent from the United Kingdom in 1931, the relationship between the monarch and First Nations continued. The British Crown in Canada became a distinct Canadian monarchy. During the 1939 tour of Canada by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, First Nations traveled to cities like Regina, Saskatchewan, and Calgary, Alberta, to meet the King and show their loyalty.

During the Second World War, over 3,000 First Nations and Métis Canadians fought for the Canadian Crown. Some received special recognition from the King. For example, Tommy Prince received the Military Medal from the King at Buckingham Palace.

Queen Elizabeth II became monarch in 1952. Squamish Nation Chief Joe Mathias was invited to her coronation in London in 1953. In 1959, the Queen toured Canada. She met with Inuit representatives for the first time. The royal train stopped in Brantford, Ontario, so the Queen could sign the Six Nations Queen Anne Bible. Across the prairies, First Nations welcomed the Queen. At the Calgary Stampede, over 300 Blackfoot, Tsuu T'ina, and Nakoda performed a war dance. The Queen walked among their teepees and met with chiefs. In Nanaimo, British Columbia, the Salish gave the Queen the title Mother of all People.

In 1970, Queen Elizabeth II's visit to The Pas, Manitoba, allowed the Opaskwayak Cree Nation to express their feelings about unfair treatment by the government. In 1973, Harold Cardinal gave a political speech to the Queen. She responded that "her government recognized the importance of full compliance with the spirit and intent of treaties." This exchange was planned beforehand.

However, Indigenous people did not always get the private time they wanted with the Queen. Meetings were often ceremonial. Treaty issues were not officially discussed. For example, in 1973, five chiefs tried to give the Queen a letter of grievances in Stoney Creek, Ontario. Officials prevented them from meeting her. In 1976, the Queen did receive First Nations delegations at Buckingham Palace.

After the Constitution Changed

Before the patriation of the Canadian constitution in 1982, some First Nations leaders worried. They felt that federal ministers had no right to advise the Queen to end treaty rights without their consent. They worried that their relationship with the monarch was being misunderstood. They felt it was seen as being under the government, which was not the original meaning of "Great White Mother" and "Indian Children."

Indigenous representatives were excluded from constitutional meetings in the late 1970s. The National Indian Brotherhood (NIB) planned to ask the Queen directly for help. The government did not want the monarch to get involved. They invited the NIB to talks, but not to the main meetings.

In 1980, the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs protested their exclusion. They organized the Indian Constitutional Express. Two trains carried about 1,000 people from Vancouver to Ottawa. They presented a petition to the Governor General. Unhappy, 41 people continued to the United Nations in New York City. They then went to Europe to share their concerns. In London, they petitioned the British parliament.

While they did not meet the Queen, their position was supported by Lord Denning. He ruled that the relationship was directly between the sovereign and First Nations. He also clarified that the Canadian Crown was distinct from the British Crown since 1931. This meant the treaties were still valid. After this, the NIB was allowed to attend meetings with premiers. After talks with Indigenous leaders, Pierre Trudeau agreed to their demands in 1982. He introduced Section 35 of the Constitution Act, which officially confirmed Aboriginal rights.

In 1994, Queen Elizabeth II visited Yellowknife. Bill Erasmus, a Dene leader, used the opportunity to present the monarch with a list of complaints about stalled land claim talks. He said the Dene's relationship with the Crown was "tarnished" because treaties had not been honored. The Queen gave a diplomatic response. She acknowledged the differences and hoped they would not lead to conflict.

Similarly, in 1997, the Queen visited Sheshatshiu in Newfoundland and Labrador. The Innu people presented a letter about stagnant land claim talks. In both cases, the chiefs gave the documents to the Queen, not the Prime Minister. The Queen then passed them to the Prime Minister to address.

The 21st Century and Reconciliation

During Queen Elizabeth II's visit to Alberta and Saskatchewan in 2005, First Nations felt they were only given a ceremonial role. They were not allowed private meetings with the Queen. Leaders also expressed concern about the relationship weakening. This was due to unresolved land claims and perceived interference in Indigenous affairs. Formal relations have not yet been established with all First Nations, such as those in British Columbia who are still making treaties.

In 1977, Queen Elizabeth II donated portraits of the Four Mohawk Kings to the National Archives of Canada. In 1984, she gave a silver chalice to the Christ Church Royal Chapel of the Mohawks. In 2003, her son, Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex, opened the First Nations University of Canada campus in Regina, Saskatchewan. The Queen visited this university in 2005.

In 2009, Shawn Atleo, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, gave Prince Charles a letter about the Crown's treaty duties. Prince Charles also linked his interest in environmentalism with First Nations' cultural practices.

In 2010, Queen Elizabeth II gave sets of handbells to Her Majesty's Royal Chapel of the Mohawks and Christ Church Royal Chapel. These symbolized the councils and treaties between the Iroquois Confederacy and the Crown.

During the Idle No More protests in 2012–2013, Chief Theresa Spence asked for a meeting with the Prime Minister and Governor General. She also wrote to the Queen. The Queen declined, stating she must follow the advice of her ministers. Spence and other chiefs held a "ceremonial" meeting with the Governor General in 2013. A separate meeting with the Prime Minister took place the same day.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission report in 2015 included 94 "Calls to Action." One request was for a new "Royal Proclamation of Reconciliation." This would build on the 1763 proclamation. It would reaffirm the nation-to-nation relationship. It would also ensure Indigenous peoples are full partners in Canada.

On Canada's first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation in 2021, the Queen said she joined Canadians in reflecting on the "painful history" of residential schools. She also spoke of the work needed to heal and build an inclusive society.

In 2022, Indigenous matters were a key theme during the royal tour of Prince Charles and Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall. Royal reporter Sarah Campbell noted that the tour openly addressed "the scandalous way many indigenous peoples have been treated in Canada." Prince Charles has been praised for listening and learning about Indigenous peoples. He finds their understanding of land and sustainability aligns with his own environmental goals.

Upon their arrival in St John's, prayers were held in Inuktitut and Miꞌkmaq music was played. Prince Charles said it was an "important moment" for Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples to reflect on the past. They also participated in moments of reflection and prayer at a Heart Garden. This garden remembers former residential school students. They also took part in a drumming circle and a feeding the fire ceremony in Dettah, Northwest Territories.

Charles met with various Indigenous leaders. In Dene, he participated in a discussion with elders and chiefs. At a reception, RoseAnne Archibald, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, asked Prince Charles for an apology from the Queen. She asked for an apology for past wrongs by the Crown and the church. She said the Prince "acknowledged" failures by Canadian governments.

Indigenous culture was also highlighted. The royal couple observed Inuit sports. The Duchess visited a school to learn about language preservation. The Prince met Canadian Rangers and saw animal furs, drums, and weapons.

Governors and Indigenous Peoples

Governors general and lieutenant governors represent the monarch in Canada. They have always been closely involved with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. This goes back to colonial times. The monarch did not travel from Europe, so they dealt with Indigenous societies through their representative. After the American Revolution, people began appealing to these representatives for help.

Governors general also met with First Nations leaders for ceremonial events. In 1867, Canada's first governor general, the Viscount Monck, welcomed a native chief at Rideau Hall. The Marquess of Lansdowne smoked a calumet with Aboriginal people. The Marquess of Lorne was named Great Brother-in-Law. The Lord Tweedsmuir was made a chief of the Blood Indians.

Five Indigenous people have been appointed as the monarch's representative in the provinces. Ralph Steinhauer was the first. He became Lieutenant Governor of Alberta in 1974. He was from the Cree nation. Yvon Dumont was of Métis heritage. He served as Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba from 1993 to 1999. The first Lieutenant Governor of Ontario of Aboriginal heritage was James Bartleman, appointed in 2002. He was a member of the Mnjikaning First Nation. Bartleman focused on encouraging Indigenous youth. He launched programs to promote reading and build bridges between communities.

On October 1, 2007, Steven Point, from the Skowkale First Nation, became Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia. Graydon Nicholas, born on the Tobique Indian Reserve, became Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick in 2009.

On July 6, 2021, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that Queen Elizabeth II had approved the appointment of Mary Simon as the 30th governor general of Canada. She met the Queen virtually due to the pandemic. When sworn in on July 26, Simon became the first Indigenous governor general in Canadian history. The Queen met Simon in person for the first time in March 2022.

Images for kids

-

Map of the North American Eastern Seaboard as divided by the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

See also

- Elijah Harper

- History of Canada

- List of Canadian Aboriginal leaders