1944 Great Atlantic hurricane facts for kids

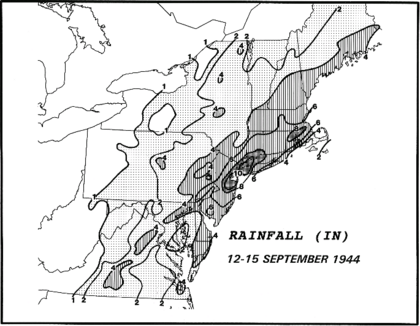

Surface weather analysis of the storm at peak intensity on September 13

|

|

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 9, 1944 |

| Extratropical | 12:00 UTC September 15, 1944 |

| Dissipated | September 16, 1944 |

| Category 5 tropical cyclone | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | ≤918 mbar (hPa); ≤27.11 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 300–400, primarily at sea |

| Damage | $100 million (1944 USD) |

| Areas affected | United States East Coast (especially New England), Atlantic Canada |

|

Part of the 1944 Atlantic hurricane season |

|

The Great Atlantic hurricane of 1944 was a very strong and damaging tropical cyclone. It swept across a large part of the United States East Coast in September 1944. New England was hit the hardest. Other areas like the Outer Banks, Mid-Atlantic states, and Atlantic Canada also felt its power. This storm was so strong that people compared it to the 1938 Long Island Express. That storm was one of the worst in New England's history.

The storm started as a weather disturbance far east of the Lesser Antilles on September 4. It became a tropical cyclone on September 9, northeast of the Virgin Islands. It moved northwest, then curved north, getting stronger all the time. On September 13, it reached its strongest point as a Category 5 hurricane north of the Bahamas. A day later, the storm passed the Outer Banks. On September 15, it made landfall on Long Island and Rhode Island as a weaker hurricane. The storm then changed into an extratropical cyclone. It moved northeast and joined another weather system near Greenland on September 16.

Contents

How the Hurricane Formed and Moved

The 1944 hurricane began as a tropical wave east of the Lesser Antilles on September 4. For a few days, it moved slowly northwest. It did not show signs of becoming a big storm. On September 7, a low-pressure area formed near Barbados. The next day, it became more organized. The Weather Bureau in San Juan, Puerto Rico started watching it closely.

Because there were not many weather stations, a special plane flew into the storm on September 9. The plane reported that it had become a full hurricane! Experts later looked back at the storm's path. They decided it likely started earlier as a weaker tropical storm. So, the official hurricane database, HURDAT, lists it as starting on September 9 with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h).

The Storm Gets Stronger

After forming, the storm slowly moved northwest and grew stronger. By September 10, it was a hurricane north of the Virgin Islands. It kept getting stronger. By September 12, it was a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Later that day, it became a Category 4 storm. The Weather Bureau in Miami, Florida called it the "Great Atlantic hurricane."

At this time, the storm also started to curve north and speed up. On September 13, it reached its strongest point. Its winds were about 160 mph (255 km/h). A ship inside the eye of the storm measured a very low pressure of 919 mbar. This showed how powerful the storm was.

The Storm Weakens and Ends

The hurricane slowly started to lose strength after September 13. On the morning of September 14, it passed east of Cape Hatteras and eastern Virginia. It was still a strong hurricane with winds of 125 mph (200 km/h). After this, it curved more to the northeast and sped up.

On September 15, the hurricane made landfall near Southampton on eastern Long Island. Its winds were about 105 mph (170 km/h). It then crossed Long Island and Long Island Sound. Two hours later, it made a second landfall near Point Judith, Rhode Island. It was a bit weaker, with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). After crossing Rhode Island and Massachusetts, the storm changed into an extratropical cyclone off the coast of Maine. These storm remains kept moving northeast across Canadian Maritimes. They were last seen joining another weather system near Greenland on September 16.

How People Got Ready

When the storm became a tropical cyclone, the Weather Bureau told ships to be very careful. They also warned people in the eastern Bahamas. The first hurricane warning was for the northern Bahamas on September 12.

In Miami, Florida, the American Red Cross started getting ready to help. Airplanes from the Royal Air Force in Nassau flew to Miami to avoid the storm. Even though hurricanes were not officially named back then, the Weather Bureau in Miami started calling this one the "Great Atlantic hurricane." They wanted people to understand how dangerous it was.

Warnings and Evacuations

The next day, storm warnings were given for the U.S. East Coast, from Savannah, Georgia to Cape Hatteras. Small boats were told to stay in port. The whole town of Morehead City, North Carolina was told to evacuate because of expected flooding. Other beach towns in North Carolina also evacuated. About 3,000 to 4,000 military staff at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point moved inland. U.S. Army and Navy planes also flew to safer places.

As the hurricane moved near the Outer Banks, hurricane warnings spread north to Portland, Maine. People in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states started getting ready. Sixty buses were prepared in Ocean City, Maryland to evacuate people. The 3,000 residents of Fire Island, a barrier island off Long Island, were ordered to leave. The Red Cross in Brooklyn got emergency supplies ready.

The First Naval District of the Navy had rescue boats and staff on standby. The Massachusetts State Police shared weather updates with local services. Police officers were called back to their stations to help later. The Massachusetts National Guard was also ready to assist. Other state agencies in Massachusetts prepared to help with relief efforts.

What Happened During the Storm

North Carolina's Experience

The hurricane passed east of North Carolina on September 14. Strongest winds were offshore, but parts of the coast felt like a Category 2 hurricane. Winds reached about 105 mph (165 km/h). The highest reported winds were in Hatteras, at 85 mph (135 km/h).

The storm caused about $1 million in crop damage and $450,000 in property damage in North Carolina. Most of this was from wind. Over 600 buildings were damaged, and 108 were destroyed. The Weather Bureau counted 3,279 damaged buildings and 389 destroyed ones. Phone lines were also cut along the coast between Morehead City and the Virginia border. One person died and 28 were hurt in the state.

Outer Banks Hit Hard

The Outer Banks were especially damaged. Strong winds pushed water from Pamlico Sound westward. Then, as the storm passed, the winds changed, pushing the water back east. This caused floods in Outer Banks villages. Storm surge along the coast destroyed hundreds of boats and boardwalks. It also left a lot of debris on the beaches.

In Hatteras, the water level rose 7 feet (2.1 m) above normal. This high water flooded coastal farms and homes with 2 to 4 feet (0.6 to 1.2 m) of water. In Avon, the water surged between sand barriers. This lifted homes off their foundations and carried them away. Ninety-six homes in Avon were badly damaged or washed away. Rodanthe was also hit hard. The storm destroyed its water systems, leaving only two homes standing.

On Roanoke Island, the storm tides were 1 foot (0.3 m) higher than any storm before. Manteo was under 6 feet (1.8 m) of water. Wanchese, at the south end of the island, saw tides reach 10 feet (3 m). The island also had wind gusts up to 120 mph (195 km/h). This caused wide damage to homes and roads. Many summer cottages in Nags Head lost their roofs. All phone and power lines along 15 miles (24 km) of the beach were blown down. One person died in Nags Head.

The storm surge and winds washed out 3,000 feet (910 m) of road connecting Roanoke Island to the mainland. Another bridge was also badly damaged. A barge broke free and hit another highway bridge at Coinjock, damaging it severely. Winds at Cape Hatteras reached about 110 mph (175 km/h).

Other North Carolina Impacts

Winds of about 75 mph (120 km/h) knocked down power and phone lines in the Elizabeth City area. The city had no power for 10 hours. The strong winds destroyed homes in the area and nearby beaches. Luckily, no one died or was hurt there. The winds also broke planes from their ties at a Consolidated Vultee airbase. Elizabeth City had about $25,000 in damage, and nearby Edenton had $10,000. Crops were heavily damaged around the Albermarle area. Homes lost roofs as far south as Morehead City. Trees and business signs were also blown down. Power outages affected New Bern, North Carolina.

Virginia's Damage

The hurricane brought Category 2 conditions to eastern Virginia. Winds at Cape Henry reached 86 mph (139 km/h). One-minute winds reached 128 mph (206 km/h), setting a record for the strongest winds measured in Virginia. Gusts at Cape Henry might have reached 150 mph (240 km/h).

The storm caused $5 million in crop damage and $1 million in property damage in Virginia. The Weather Bureau reported 2,132 damaged buildings and 31 destroyed ones.

The Richmond Times-Dispatch called the storm "unusually violent." Wind gusts in the Hampton Roads area were over 80 mph (130 km/h). The Norfolk and Virginia Beach areas were hit hardest in Virginia. Homes were damaged, and phone and power services were cut in both cities. The main power line between Norfolk and Virginia Beach was knocked out. A power station in Suffolk also went down. The 200-foot (61 m) radio tower for WSAP in Portsmouth was blown down. Damage was minor in Gloucester and Matthews counties. However, high tides forced people living near the coast to move to higher ground.

New Jersey Shore Damage

The hurricane caused a lot of damage along the New Jersey coastline. Towns like Long Beach Island, Barnegat, Atlantic City, Ocean City, and Cape May were all badly hit. Long Beach Island, Barnegat Island, and Brigantine lost their roads connecting them to the mainland. This cut them off from the rest of New Jersey. Also, both islands lost hundreds of homes. In Harvey Cedars on Long Beach Island, many homes were swept into the sea.

In Atlantic City, the storm surge pushed water into the lobbies of many famous hotels. The Atlantic City boardwalk was badly damaged. The Boardwalk Hall Auditorium Organ and the city's famous ocean piers were also hit. Both the famous Steel Pier and Heinz Pier were partly destroyed. Only the Steel Pier was rebuilt. Ocean City and Cape May also lost many homes. Ocean City's boardwalk was significantly damaged. Larry Savadove wrote a whole chapter about this hurricane in his book Great Storms of the Jersey Shore.

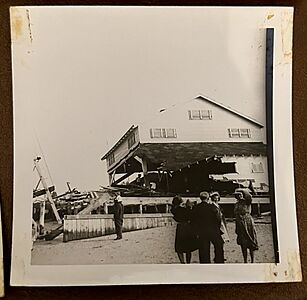

- Damage photographed in Atlantic City on 9-14-44

-

What’s Left of the Boardwalk

New England's Experience

The Hartford, Connecticut area received about 7 inches (178 mm) of rain. The city of Bridgeport had the most official rain, with 10.7 inches (272 mm). Tobacco and fruit farms in Connecticut lost about $2 million (in 1944 money). Rhode Island had similar damage costs. Over $5 million (in 1944 money) in damage on Cape Cod came from lost boats, fallen trees, and broken power lines. A total of 28 people died in New England because of the storm. Many tree branches were blown down by strong winds. In Androscoggin County, Maine, 40% of the apple crop was destroyed.

Hey Bonnie Hall, a large house in Bristol, Rhode Island, was so damaged it could not be fixed. It was torn down later in 1944.

Ships Lost at Sea

The storm also sank the Navy destroyer USS Warrington. This happened about 450 miles (725 km) east of Vero Beach, Florida. Sadly, 248 sailors were lost. The hurricane was one of the strongest to hit the Eastern Seaboard. It was a Category 4 storm when it met the Warrington. It had hurricane-force winds over an area 600 miles (965 km) wide. The hurricane also created waves over 70 feet (21 m) high. The story of the hurricane and the sinking of USS Warrington is in the 1996 book The Dragon's Breath - Hurricane At Sea.

Besides the Warrington, two Coast Guard cutters, USCGC Bedloe (WSC-128) and USCGC Jackson (WSC-142), also sank off Cape Hatteras. Seventy-five men got onto life rafts from these two ships. But only 32 survived the rough seas and cold for two days until they were rescued. The 136-foot (41 m) minesweeper YMS-409 sank, and all 33 people on board died. The lightship Vineyard Sound (LV-73) also sank, and all twelve people on board were lost. YAG-17, a large attack transport simulator, was wrecked. Finally, the hurricane pushed the SS Thomas Tracy onto the shore in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware.

See also

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |