First Russian circumnavigation facts for kids

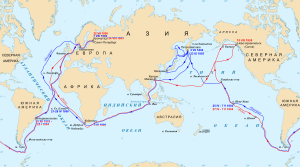

Quick facts for kids The First Russian circumnavigation |

|

|---|---|

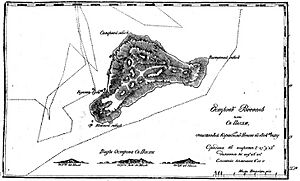

Harbour of St Paul on the Island of Cadiack, Russian sloop-of-war Neva |

|

| Type | Circumnavigational expedition |

| Target | Kronstadt Island, Saint Petersburg |

| Executed by | Adam Johann von Krusenstern, Yuri Lisyansky |

The first Russian circumnavigation of the Earth was a big journey around the world. It happened from August 1803 to August 1806. Two ships, the Nadezhda and the Neva, made this trip. They were led by Adam Johann von Krusenstern and Yuri Lisyansky.

The main goals of the expedition were to make new friends and trade partners for Russia. They wanted to build relationships with Japan and with Chinese ports to sell Russian furs. A special group, led by Nikolai Rezanov, joined to help with diplomacy. Rezanov was also a top representative for the Russian-American Company. However, Rezanov and Krusenstern often had different ideas about what was most important for the trip.

The ships started their journey from Kronstadt on August 7. They made stops in places like Copenhagen, Falmouth, Cornwall, Tenerife, Brazil, Nuku Hiva, and Hawaii. When they reached the Hawaiian Islands in June 1804, the ships went separate ways. The Nadezhda sailed to Kamchatka and Japan. The Neva went to Kodiak Island, Alaska. There, it stayed for 14 months and even helped in a conflict called the Russian-Tlingit war.

The ships met again in Guangzhou in December 1805. After leaving China, they sailed together for a short time. Then, they returned to Kronstadt separately in August 1806. The trip was not fully successful in making diplomatic ties with Japan. Japanese leaders did not let the Russian ambassador enter the country. They also refused to start official relations.

Despite the challenges, the expedition discovered many new places in the Pacific Ocean. They named and described islands, capes, and straits. Many people on the trip wrote books about their adventures. Some of these diaries were only published much later.

Contents

Why the Journey Happened

For a long time, Russia wanted to sail around the world. As early as 1722, people suggested sailing from Kronstadt to Kamchatka. However, the Russian Navy was not strong enough for such big plans for many years.

In the 1780s, other countries like Great Britain, France, and the United States became very active in the North Pacific. This made Russia worried about its own interests in the Far East. Russia wanted to explore and claim more land, especially in the Aleutian Islands. To do this, they needed good maps. But a large part of Alaska was not well-mapped by Russians.

In 1785, Joseph Billings led an expedition to explore the Northeast Passage. This trip was sped up when Russia heard that Jean-François de Galaup was also planning a round-the-world voyage.

In 1786, Catherine the Great ordered ships to sail to Kamchatka. The goal was to explore and claim islands like the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin. They planned to place pillars with the Russian emblem to show ownership. However, wars with Turkey and Sweden stopped this plan. The leaders of this planned trip, Grigory Mulovsky and James Trevenen, died in battles.

For years, merchants like Grigory Shelikhov also tried to get ships to sail from the Baltic Sea to Russian America. But supplies continued to be sent overland through Siberia.

Adam Johann von Krusenstern had served under Mulovsky and knew about his plans. Later, Krusenstern, along with Yuri Lisyansky, spent six years sailing with the British merchant fleet. They traveled to North and South America, India, and China. During these trips, Krusenstern realized how important it was to supply Russian America by sea. He also saw the benefits of trading furs with China.

In 1799, Krusenstern presented his idea for a new expedition. He wanted to supply Russian America and trade furs with China. At the same time, the governor of Irkutsk also suggested building trade ties with Japan. But wars with France delayed these plans.

Planning the Journey

Krusenstern's Idea and Company Support

Krusenstern kept pushing his idea for a round-the-world trip. A new chance came when Emperor Alexander I was in charge. Russia needed money because of wars with France. Krusenstern's plan focused on Russia's business interests. He wanted the government to support private companies to develop shipping in the Pacific. This would help Russia compete with England and the United States in the fur trade. It would also strengthen Russia's role in Chinese and Japanese markets.

On July 26, 1802, Emperor Alexander I personally approved Krusenstern's project. He allowed Krusenstern to lead it himself. Soon after, Minister of Commerce Nikolay Rumyantsev and Nikolai Rezanov (from the Russian-American Company) proposed a very similar plan. Their project aimed to deliver goods to Russian America, strengthen Russia's presence in the Pacific, and start trade with China. They also suggested settling the Urup island and trading with Japan through the Ainu. They asked for a large loan to pay for the expedition.

Choosing Leaders and Setting Goals

The government approved the plan from the Russian-American Company. Krusenstern was eventually chosen as the main commander of the two ships. Yuri Lisyansky was also hired by the company. At first, the expedition faced money problems. The Russian-American Company could only pay for one ship. So, the government agreed to pay for the second ship's equipment and upkeep.

The main goals of the expedition were political. They wanted to explore the Amur river mouth and nearby areas. This was to find good routes and ports for the Russian Pacific fleet. Another important goal was to "establish trading routes." This meant taking commercial goods to Alaska. On the way back, they aimed to start trade with Japan and Canton (Guangzhou).

The expedition also carried 325 medals. These were meant as awards for Russian settlers and native people. The idea to send someone to Japan, led by Rezanov, was first mentioned in February 1803. Emperor Alexander approved this plan in June 1803.

Rezanov was not a career diplomat. He had worked in the court of Catherine II. In July 1803, Rezanov received a high court rank and an important award. He was also made an honorary member of the Academy of Science. He was given the title of Extraordinary Envoy and Minister Plenipotentiary. Some historians believe his appointment to Japan and Russian colonies was a way to send him away from the main court. He also received unclear instructions, which led to conflicts with Krusenstern and the naval officers.

The expedition's final plan was for the two ships to reach the Hawaiian Islands. From there, Lisyansky would take the Neva to Russian America. Krusenstern would take the Nadezhda to Japan. After spending the winter in Kamchatka or Kodiak Island, the ships would meet in Canton to trade furs. Krusenstern could choose the return route himself.

Getting the Ships Ready

It's not clear why the Russian-American Company decided to buy ships from other countries. The Russian navy had suitable ships. But the company sent Lisyansky to England to buy two sloops. He bought the 16-gun Leander, which was renamed Nadezhda. He also bought the 14-gun Thames, which became the Neva.

Some officers thought Lisyansky bought old ships for too much money. The Nadezhda was built around 1795 and had been damaged before. Its front mast was broken, and parts of its hull were rotting. The Neva was in slightly better shape, but its ropes and sails needed to be replaced.

The ships were not fully repaired in Russia. Instead, the main masts of the Nadezhda were replaced in Brazil. This cost a lot of money. The ships were in poor condition. The Nadezhda especially leaked a lot in stormy weather. There was even talk of abandoning it when they reached Kamchatka.

Who Was on Board?

In total, 129 people were on the two ships. 84 of them were on the Nadezhda. The crew included officers, sailors, and Rezanov's diplomatic team. There were also officers from the Russian-American Company. Five Japanese survivors of a shipwreck were also on board, returning home.

Most of the officers and passengers were young. The oldest were a 42-year-old doctor and 39-year-old Rezanov. Krusenstern was 33. The youngest were 13 and 15-year-old cadets. Krusenstern chose Russian volunteers as sailors.

The commanders had different ways of leading. Krusenstern believed in treating his crew kindly. Lisyansky, however, was very strict on the Neva. He used harsh discipline.

Even though the expedition was mainly for trade, Krusenstern also wanted to do scientific work. He created a "scientific committee." They hired Swiss musician and astronomer Johann Caspar Horner. He was known for his courage. The main artist was Wilhelm Gottlieb Tilesius von Tilenau, a botanist and zoologist. Doctor Georg von Langsdorff joined the crew to study nature. Karl Espenberg was the doctor on the Nadezhda. Moritz Laband was the doctor on the Neva.

Many officers were of German background and spoke different German dialects. Scientists often didn't know Russian at first. Communication with the crew was in Russian.

Life on the Ships

The ships were very crowded with cargo and people. This meant they didn't have much space for fresh water or food. The crews mostly ate crackers and salted beef. To prevent scurvy, a disease caused by lack of vitamin C, they ate sauerkraut (fermented cabbage) and drank cranberry juice.

Living conditions were tough. Even officers had small cabins, only big enough for sleeping. The main common areas were the only places for research or writing. On the Nadezhda, about twenty people shared this space. On the Neva, there were ten. Krusenstern and Rezanov shared a small cabin, about 6 square meters, with no heating or good lighting. For 84 people, there were only three toilets.

The constant lack of fresh water made washing difficult. They also kept animals like cows and pigs on board for food. The pigs were even washed in the Atlantic Ocean!

Officers had the hardest time. They had to stand watch, record weather, write journals, and train the crew. This often led to stress. For example, on the island of Nuku Hiva, the artist Kurlyandov became so stressed that he smashed his cabin with an axe.

Scientific Tools

The expedition members saw themselves as following in the footsteps of famous explorers like James Cook and Lapérouse. They even visited places where Cook had been.

The Russian Academy of Sciences gave instructions to the scientists. They had guides for studying minerals, plants, and animals. They were told to record exact dates, classify samples, and sketch what they saw. However, some scientists did not always follow these rules.

Krusenstern and astronomer Horner used chronometers to find their exact location. They also tried to record weather data regularly. But the rocking of the ship often affected their instruments. In Japan, one of the main instruments broke. They measured ocean temperatures at different depths for the first time on this trip.

The Nadezhda had a library with books belonging to officers and scientists. Krusenstern's own collection formed the core of it. It included maps, astronomy books, and travel guides.

The Journey Begins

From Kronstadt to Brazil (August - December 1803)

Sailing the Baltic Sea

The expedition ships arrived in Kronstadt on June 5, 1803. Krusenstern quickly saw that the Nadezhda needed major repairs. Its ropes and two masts had to be replaced. Thanks to the port captain, repairs were done quickly. On July 6, Emperor Alexander I inspected the ships.

The departure was delayed by bad winds and too much cargo. On August 2, Minister Rumyantsev visited the ships. He ordered them to get rid of unnecessary cargo when they stopped in Copenhagen. Five people from Rezanov's group were also removed from the trip. The expedition finally left on August 7.

Life on board was strict. The commander set schedules for shifts and food. People received a pound of beef and crackers daily. They also got a cup of vodka (or money if they didn't drink) and a pound of oil per week. Meals were simple, usually one main dish.

On August 17, the expedition reached Copenhagen. They had to reload the ships, take on the scientific team, and load French brandy for the Russian-American Company. They also had to replace almost all their food supplies because the crackers and salted beef were spoiled. This long stop led to the first arguments between Krusenstern and Rezanov.

To the Canary Islands

On September 8, the ships sailed again. A storm kept them in Helsingør for six more days. During this time, the crews ate fresh meat and greens daily.

Strong storms separated the ships near Skagerrak. The weather improved by September 20. On September 23, Krusenstern met an English ship. Its commander, Beresdorf, was an old friend. Beresdorf took Rezanov and astronomer Horner to London for business. This saved time.

On September 27, the Nadezhda reached Falmouth, Cornwall, where the Neva was waiting. They decided to buy Irish salted beef, fearing the Hamburg supply would spoil. Both ships were leaking badly. Krusenstern hired workers to seal the leaks. They also had to bring fresh water from miles away.

The ships were very damp inside. To keep them dry, the crews opened hatches and used burning coals and vinegar. Sailors were ordered to wash twice a week. In tropical areas, they were even poured with seawater.

The ships left for the Canary Islands on October 5. The weather quickly became warmer. On October 19, they reached Tenerife. On October 20, they arrived at Santa Cruz de Tenerife. The Neva lost some equipment because of the rocky seabed.

They stayed in Tenerife until October 27 to get supplies. They bought fresh vegetables, fruits, potatoes, and wine. Rezanov stayed with a merchant, and Horner set up his observatory. The crew noticed the poverty and strict rules of the Spanish Inquisition on the island. They also had to ban locals from visiting the ships due to theft. Before leaving, Rezanov openly called himself the head of the expedition. This caused a big argument with Krusenstern. Rezanov later apologized, but he also complained to the emperor.

Crossing the Equator

On October 27, the ships sailed towards the Cape Verde Islands. To avoid calm waters, they passed the islands from a distance on November 6. In equatorial waters, the weather was hot and foggy. It was hard to dry clothes. Krusenstern ordered heating the living areas and giving the crew potatoes, pumpkins, wine, and weak punch. Frequent rains allowed them to collect fresh water for two weeks. They even turned the ship's awning into a pool for bathing.

On November 26, at 10:30 PM, the ships crossed the equator. The crews cheered loudly. A special ceremony was held the next day. Krusenstern, who had crossed the equator before, led it. The Neva crew received a special meal with soup, fried ducks, pudding, and beer.

The ships then searched for Ascension Island, but couldn't find it. They believed it might not exist.

Brazil (December 1803 — February 1804)

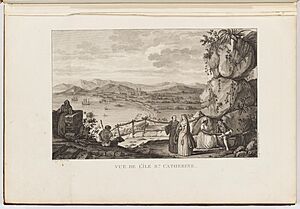

Following the example of Lapérouse, Krusenstern chose the port of Florianópolis in Brazil. It had a better climate, fresh water, and cheaper food than Rio de Janeiro. On December 21, the ships entered the strait and anchored near Santa Cruz fortress. The governor, Joaquim Xavier Curado, welcomed them warmly.

The main reason for their long stay in Brazil was to replace the Neva's front and main masts. This work lasted from December 26, 1803, to January 22, 1804. The ship was unloaded, pulled ashore, and thoroughly sealed. Rotten parts were replaced. Suitable wood was found in the island's forests. This work cost about 1300 piastres. To stay healthy, the crews drank tea and weak grog instead of water.

During their five-week stay, officers and scientists explored the area. Many were upset by slavery.

The conflict between Krusenstern and Rezanov grew worse in Brazil. On December 28, Rezanov tried to stop Count Tolstoy from going ashore. Krusenstern canceled this order. On December 29, Krusenstern held a meeting with his officers. He asked them to define Rezanov's powers. The officers agreed they would not follow orders from Rezanov that did not serve the emperor or the expedition. Rezanov tried to give orders to Lisyansky directly, but no one obeyed. The officers wrote a letter to the emperor about the situation. After this, things calmed down.

Crossing the Pacific Ocean (February – June 1804)

Cape Horn and Easter Island

On February 2, 1804, all repairs were finished. Rezanov and his group returned to the ship. The governor gave them a salute. But strong winds delayed their departure until February 4. The original plan was to go around Cape Horn in January.

The ships approached Cape Horn on February 25. They sailed south to avoid coastal cliffs. The weather was very cold, and the crews received winter clothes. Lisyansky ordered pea soup and more vegetables. On March 3, the expedition reached the Pacific Ocean.

During a storm on March 25, the ships lost sight of each other. Since the nearest land was far away, Lisyansky decided to head for Easter Island. The storm was so strong that Lisyansky, who usually doubted things, started thinking about God.

On April 1, the weather improved. The crew set up a forge on the Neva's deck. They made axes, knives, and nails to trade with native people. The Neva reached Easter Island at 1 AM on April 15. The crew could see the famous moai statues and farms. But bad weather kept the ship from getting close to shore for four days.

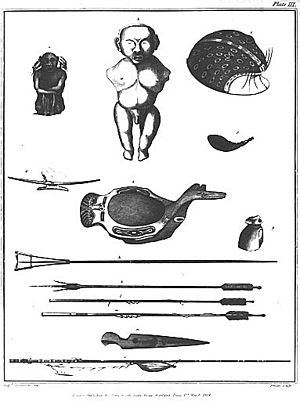

On April 21, Lisyansky sent Lieutenant Povalishin ashore with gifts. He also wanted to leave a message for Krusenstern in case the Nadezhda arrived. The islanders happily traded bananas, yams, sweet potatoes, and sugarcane for mirrors, scissors, and knives. Povalishin managed to get a boat full of food and some local crafts. Lisyansky corrected the island's coordinates and estimated the number of people living there.

Nuku Hiva Island

The storm that separated the ships lasted until March 31. The weather improved by April 8. On April 10, the Nadezhda had its first warm day, which the crew used to clean the cannons.

Doctor Espenberg checked everyone's health. Despite the lack of fresh water and long time in bad weather, everyone was healthy. Krusenstern decided to go straight to Nuku Hiva to deliver the company's cargo quickly. The blacksmith made nails, knives, and axes for trade.

On May 5, after a heavy storm, the crew saw the islands of Fatu-Hiva, Hiva Oa, and Ua Huka. The ship reached Nuku Hiva around 5 PM. Krusenstern and his crew stayed on the Washington Islands (part of the Marquesas Islands) for 11 days. They used Anna-Maria Bay as their base. They made contact with the local leader, Kiatonui, with the help of an Englishman named Roberts.

The expedition needed fresh water and food. Local tribes offered coconuts, bananas, and breadfruit. The most valuable trade item was pieces of barrel iron hoops. Islanders sharpened these to make tools. On May 11, the Neva also arrived at the island. Lisyansky met Krusenstern and the local leader. They couldn't get much fresh meat because the locals had few pigs.

On May 12, there was an incident. The leader Kiatonui stayed too long on the Nadezhda. His tribe thought he was captured and got ready to fight. Sailors were getting fresh water, and islanders helped carry barrels through the waves.

Krusenstern and Lisyansky told officers, sailors, and scientists not to visit the island alone. They could only go ashore in groups led by officers.

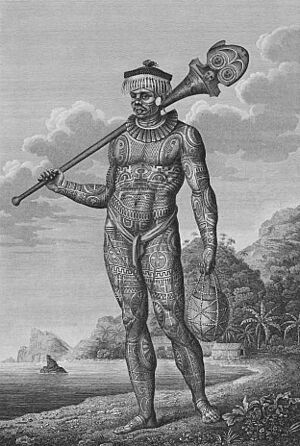

The crew was fascinated by the local tattoos. Marquesans tattooed their entire bodies. Sailors also got tattoos. Krusenstern even had his wife's name tattooed on his arm. Count Tolstoy got his first tattoo there.

A big argument happened between Krusenstern and Rezanov on Nuku Hiva. Krusenstern had forbidden trading axes for local items, wanting to save them for pigs. Rezanov and a merchant ignored this order. This caused the value of iron hoops to drop. Shemelin, the merchant, later wrote that it became impossible to buy pigs because of this trade crisis. Rezanov also ordered collecting many rare items for a museum.

On May 14, a public argument took place between Rezanov and Krusenstern. Shemelin and Lisyansky were also involved. Rezanov called Krusenstern's actions "childish." He said that collecting museum items was a direct order from the emperor. Krusenstern replied that he did not obey Rezanov. Officers from both ships demanded Rezanov show his official instructions. Lisyansky even said that Emperor Alexander "can sign up pretty much everything."

Lisyansky wrote to Krusenstern the next day, saying, "Before today I considered myself in your command, but now it turns out that I have another commander." This showed the deep disagreement.

On Nuku Hiva, Krusenstern discovered a great harbor. He named it Chichagova. Before leaving on May 17, a strong storm hit. The Nadezhda almost crashed. Krusenstern saved the ship by using ropes and sacrificing an anchor. A Frenchman named Cabri accidentally stayed on board during the storm. He later claimed Krusenstern forced him to stay. Rezanov stayed in his part of the captain's cabin until they reached Kamchatka to avoid more conflict.

Journey to Hawaii

The ships needed to visit the Hawaiian Islands to get more supplies. Krusenstern worried about scurvy because they couldn't get fresh meat on Nuku Hiva. Lisyansky started hunting sharks.

On June 8, the island of Hawaii became visible. Locals in boats approached the ships to trade. They offered small items. The next day, they brought a pig, but the crew didn't have the clothes the locals wanted for trade. The Nadezhda also developed a big leak because the ship was lighter and its old caulking was falling apart. Sailors had to pump water out daily.

The Neva stayed in Hawaii until June 16. On shore, they found an Englishman named Jung who managed local trade. On June 12, they started bargaining. They bought two pigs and roots for axes and rum. Officers and sailors bought local crafts. Jung had forbidden selling pigs, but a Hawaiian foreman still brought two big pigs, goats, hens, sweet potatoes, and coconuts. Lisyansky did not allow women on the ship.

Lisyansky visited the place where James Cook died. He also saw a pagan church and a shipyard. On June 15, American fishermen told the commander about a conflict in Sitka. On June 16, the crews bought eight more pigs. Lisyansky calculated they had enough food for Alaska. On June 17, the Neva sailed towards Maui and then directly to Unalaska Island.

Nadezhda in Kamchatka, Sakhalin, and Japan (July 1804 – 1805)

Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky and the Japan Embassy

Krusenstern planned his route to Kamchatka to be similar to James Cook's. On July 13, Kamchatka's shore appeared. On July 15, the ship reached Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. The journey from Hawaii took 35 days. Only one person showed signs of scurvy, but recovered quickly.

Rezanov and his group went ashore immediately. The port commander, Major Krupsky, helped them settle. The crew received fresh bread and fish to recover from their long journey. The ship was repaired.

On June 30, during the unloading of embassy goods, Rezanov openly attacked Krusenstern. He threatened to punish all officers. The governor, Koshelev, had to get involved. There was no official proof for Rezanov's claims. Krusenstern offered his sword to the general, demanding to be sent back to Petersburg. But the officers supported Krusenstern. Ratmanov said that Rezanov "came to his senses" and sought an agreement. He persuaded Krusenstern to go to Japan, after which he would leave the ship.

On August 16, an official truce was made. Rezanov wrote to the emperor, praising Krusenstern. However, their relationship remained tense.

Before leaving for Japan, Count Tolstoy, botanist Brinkin, and painter Kurlyandov left the ship. They would travel back home by land. They had become disliked on board. Rezanov took an "honor guard" of soldiers to fill the empty spots. They left for Japan on August 30.

The Failed Mission to Japan

The journey to Japan was stormy. On September 11, a huge storm hit. The ship leaked more, and they had to kill four bulls they got in Kamchatka because the animals couldn't handle the rocking. Japan became visible on September 28. Existing maps were not accurate.

On October 3, the ship reached Satsuma Domain. The local government informed the governor of Nagasaki. The expedition then sailed through the Osumi Strait, which they were the first Europeans to describe. The Nadezhda reached Nagasaki strait on October 8. Rezanov had papers from the Dutch to help with his mission.

Russia's leaders were not focused on relations with Eastern countries at this time. Rezanov's instructions told him to "make decisions according to Japanese customs and do not abase oneself." The emperor's letter was addressed to the "Emperor of Japan," meaning the Shogun. Rezanov was supposed to make a trade agreement. To gain favor, they brought home Japanese sailors who had been shipwrecked. Rezanov also had 50 boxes of gifts, mostly glass, crystal, mirrors, porcelain, and furs. However, fox furs, which were valuable in Russia, were not liked in Japan. The only things that interested the Japanese were an English clock shaped like an elephant and kaleidoscope lights made by a Russian inventor.

Japanese officials sent low-ranking translators. They demanded the same strict ceremonies as for the Dutch. Krusenstern, Rezanov, and the merchant Shemelin argued about how many times to bow. The Japanese didn't understand why the Russians were upset.

The Nadezhda needed repairs. The crew had to agree to disarm the ship. They put all their gunpowder in a Japanese arsenal and gave up their cannons and anchors. They were allowed to keep their swords, and the honor guard kept their guns. Rezanov tried to make the crew humble themselves before the Japanese. But he himself acted arrogantly, which made the Japanese suspicious.

The ship was moved to the inner harbor in Nagasaki on November 9, a month after arriving. Rezanov was given a house and warehouses, but it felt like a prison. Rezanov was tired from the long journey and constant disputes. He often argued with his group and translators. His every move was watched.

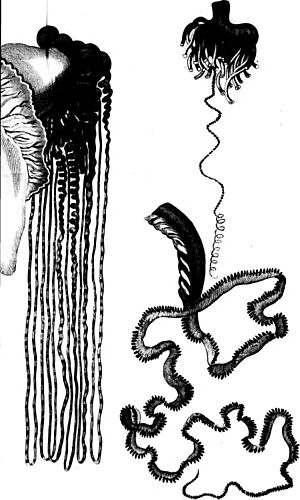

Sailors on the Nadezhda were even more restricted. They could only go ashore to a small, fenced area, like a prisoner's yard. It had three trees and a small shelter. Despite this, officers on the Nadezhda were able to make more maps and observations in a short time than the Dutch had in 300 years. Scientists like Langsdorf and Tilesius studied the climate and fish. They convinced local fishermen to bring them new types of fish daily. Langsdorf collected 400 fish specimens of 150 different kinds. He also launched silk and paper balloons, which upset Rezanov.

Rezanov knew some Japanese language. But he didn't realize the Japanese around him were skilled scholars. The most famous Japanese scientist, Otsuki Gentaku, later wrote a book about the Russian officers and researchers.

Rezanov's actions made negotiations difficult. He even pretended to be sick to pressure the governor. He demanded Japanese doctors, even though he had two doctors with medical degrees on his own team. Japanese doctors visited him and found no serious illness. Rezanov later said he did this to show trust. He also took 500 Japanese caskets as a "deposit" for trade, but when trade didn't happen, he kept them.

Finally, on April 4 and 5, Rezanov met with Japanese officials. The meeting went badly. The Japanese rejected any trade relations. On April 7, there was a farewell ceremony. The Russian gifts were not accepted. But the Japanese paid for ship repairs and gave the crew food for the trip back to Kamchatka. This included rice, salt, silk wool, dried bread, sake, salted fish, and live cattle. It took ten days to load everything.

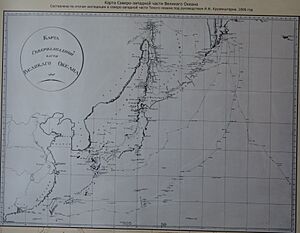

Second Visit to Kamchatka

Krusenstern decided to return to Petropavlovsk through the Sea of Japan. This route along the west coast of Honshu and Hokkaido was not well known to Europeans. Stormy weather continued. On May 1, the ship reached the Tsugaru Strait. Krusenstern wanted to find a strait that was on his map, dividing Hokkaido from Sakhalin. On May 7-9, he realized that Karafuto on his map was Sakhalin. The expedition then went through the La Pérouse Strait, correcting many map errors.

On May 14, the Nadezhda anchored in Aniva Bay. Langsdorf and Ratmanov explored the shore. Rezanov and Krusenstern met local Nivkh people. Krusenstern thought it would be good to set up a Russian trading post there. The Nivkh people offered sailors rice and fresh fish. On May 16, the expedition rounded Cape Aniva. On May 17, they arrived in the Gulf of Patience. They discovered new capes, named after Mulovsky and Soymonov. On May 24, thick ice blocked their way. They discovered four more islands. After a big storm, on June 5, the crew arrived back in Petropavlovsk.

During the trip to Kamchatka, one of the honor guards got smallpox in Japan. Krusenstern was worried about the disease spreading in Petropavlovsk. He found that most of the crew from St. Petersburg had been vaccinated. The sick soldier's belongings were thrown into the sea. Other items were treated with sulfur or washed in boiling water. The soldier was quarantined for three weeks, and the crew was not allowed to talk to locals.

Later, they learned that Emperor Alexander I had sent a message. Krusenstern received an award. Rezanov received a diamond snuff box. Rumyantsev also asked Rezanov to explore the American coast from Kodiak Island to the Bering Strait. Langsdorf decided to go with Rezanov to study Russian America's natural resources. Some people left the Nadezhda at Petropavlovsk.

Exploring Sakhalin

The ship was supposed to leave on June 21, but the governor was away. Also, a boiler needed repair. On June 25, Rezanov left for the New World on another ship. On July 1, Governor Koshelev arrived. Krusenstern found out Rezanov had written many letters to St. Petersburg. Fearing complaints, Krusenstern sought the governor's support.

On July 5, Krusenstern sailed into the open sea. He wanted to find islands he couldn't locate before. The crew also mapped the coast. On July 19, the weather was perfect for science. They found new capes, including Cape Bellingshausen. On August 9, the expedition reached the northern part of Sakhalin. Krusenstern thought the newly discovered northern strait was a safe harbor. They found a settlement of Nivkh people. On August 12, the Nadezhda entered the channel between Sakhalin and the mainland. The water was so fresh that Krusenstern thought the Amur river mouth was nearby. The water depth was very shallow. Krusenstern decided not to risk it and concluded that Sakhalin was a peninsula. He suggested another expedition to explore the Tatar Strait. This was done much later, in 1849, by Gennady Nevelskoy.

Due to fog and storms, the exploration of Sakhalin took a long time. The Nadezhda was supposed to meet the Neva in Guangzhou. An attempt to finish mapping the Kuril Islands failed due to fog. On August 30, everyone returned safely to Petropavlovsk. Despite the constant rain and lack of fresh food, no one on the ship was sick.

News was disappointing. Supplies from Okhotsk had not arrived. On September 2, a transport arrived with mail and instructions from Rumyantsev. The Nadezhda needed new ropes and sails. They loaded ballast and firewood for the return trip. The food from Okhotsk was bad. They only took salted beef for three months and crackers for four months. By the time they reached China, the crackers were only fit for livestock.

Because of the delays, officers decided to fix the grave of Captain Charles Clerke. On September 15, they built a pyramid from birch wood. On September 20, a ship from Unalashka arrived with news from Lisyansky and furs for sale in China. The governor's brother brought potatoes, vegetables, berries, and bulls. Finally, on October 5, the Nadezhda sailed into the open sea.

Before leaving, the crew learned about new changes to the merchant flag. From Kamchatka to China, the Nadezhda sailed with a new nine-stripe flag.

Neva in Russian America (August 1804 – November 1805)

Battle for Novo-Arkhangelsk

The Neva's journey from Kauai to Kodiak took 25 days. The weather was rainy and cold. Many people got stomach problems from the fresh pork, but they were cured with medicine. The ship arrived on July 10. Hieromonk Gideon, a priest, went ashore in Kodiak to work at a school.

When the Neva arrived, it found itself in the middle of a conflict. On July 13, Lisyansky received a request from merchant Alexander Andreyevich Baranov. Baranov asked for help to free Sitka from the Tlingit people. Baranov had his own ship, 120 armed Russian hunters, and 800 native allies. The 14-gun sloop Neva greatly strengthened his forces.

Talks with the Tlingit leader, Kotlean, failed. Baranov wanted the fortress to surrender. On October 1, 1804, naval guns fired at the Tlingit defenses. But the guns were too small, and the thick wooden walls protected the Tlingit. Lisyansky sent troops with a field gun. Baranov and Lieutenant Povalishin attacked from another side. The Tlingit fought back with small cannons and rifles. Povalishin was injured, and several sailors were wounded or died. Still, the Tlingit's position was hopeless. On October 2, both sides started talks. By October 7, most of the Tlingit forces had fled through the mountains. As a result of this conflict, a new fortress called Novo-Arkhangelsk was built. Russian control in the area expanded.

Winter in Kodiak

Winter was coming. On November 10, 1804, the Neva returned to Kodiak. By November 16, the ship was prepared, and the crew moved ashore. The winter lasted 11 months. The crew lived in comfortable homes and spent time fishing and hunting. They even put on a play and built an ice slide.

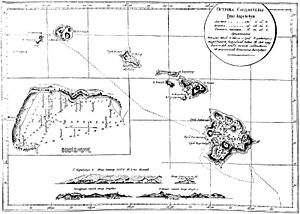

Preparations for departure began on March 20, 1805. Lisyansky and a navigator explored the Kodiak archipelago by canoe. They made a map of the area.

The Russian-American Company's manager, Nikolay Korobitsyn, made decisions for this part of the expedition. He was supposed to load furs for trade in China. The Neva brought goods worth 310,000 rubles from St. Petersburg. It received furs and walrus bones worth 440,000 rubles. The crew also had to make a new bowsprit for the ship. This delayed their departure until June 13. The expedition left Pavlovsk Harbor on November 16. On June 22, the Neva arrived in Novo-Arkhangelsk. New wooden buildings had been built there. Lisyansky visited ruler Baranov. From July 2 to 7, navigator Kalinin explored Kruzof Island and Mount Edgecumbe. Lisyansky was so interested in Mount Edgecumbe that he climbed it.

Journey to China

On September 1, 1805, the Neva sailed into the open sea after saying goodbye to Baranov. Lisyansky took two native kayakers and four Russian-Indian mixed-race people on board to teach them sailing. On September 2, the ship faced a huge storm.

Lisyansky also wanted to find unknown lands east of Japan. On October 15, at 10 PM, the Neva ran aground on corals. The crew threw spare parts and guns overboard to pull the ship into deeper water. But in the morning, a storm pushed the ship back onto the corals. The keel was damaged, but the crew managed to fix the problem. They even recovered the items they had thrown overboard. This is how they discovered an uninhabited island, which was later named Lisyansky Island.

By October 31, the crew had only 30 days of dried bread left. Their food portions were reduced. On November 16, they saw the Tinian island and then the Northern Mariana Islands. On November 22, the ship went through a heavy storm. Three sailors were thrown overboard but managed to grab onto ropes and were saved. The water level in the ship's bottom increased, and the crew had to pump it out.

On November 23, a bad smell came from the main cargo hold. The next day, they opened it and found spoiled furs. They threw furs worth 80,000 rubles into the sea. Lisyansky moved the crew to the officers' mess until the hold was cleaned.

From Canton to Kronstadt (November 1805 – August 1806)

Staying in China

Leaving Avacha Bay on October 9 was dangerous due to fog and snow. The constant waves, cold, and storms made the journey difficult. Krusenstern risked searching for islands shown on old Dutch and Spanish maps, but these islands were later found not to exist. On November 17, while passing the Taiwan Strait, a strong storm hit. The old sails tore, and new ones had to be put up. The ship anchored near Macau on November 20. The British almost captured the ship, mistaking it for Spanish, because the Nadezhda was flying a new, unfamiliar commercial flag.

Krusenstern wanted to work with the British East India Company director in Guangzhou, J. Drummond. By this time, the trade season had started. The presence of the Nadezhda in the bay broke many rules for foreign ships in China. Krusenstern was also worried because the Neva had not arrived yet. On December 3, Lisyansky finally arrived. The Russian ships moved to Huangpu Island at the mouth of the Pearl River.

Krusenstern hoped that the Russian embassy was already in Beijing and that trade agreements would be made. But the embassy had not even crossed the Chinese border. The Russian ships caused a stir among Chinese officials. However, the customs manager allowed them to enter the port of Canton, likely to charge duties. The governor hesitated to give permission, which meant merchants couldn't make deals. A typhoon season had also started, risking another year's delay. The British helped, especially the firm Bil' and Moniak.

The trade deal did not bring the expected profit. They sold furs for about 191,621 Spanish piastres. With this money, they bought tea, silk fabrics, porcelain, and pearls. After paying commissions and taxes, they had much less profit. The situation was so bad that they decided to bring the best furs back to St. Petersburg. For example, beaver skins, which were worth 200-300 rubles in Moscow, sold for only 20 piastres (100 rubles) in China.

The total cargo included 832 boxes of tea and 20,000 pieces of silk fabric on the Nadezhda. The Neva carried 1201 boxes of tea and unsold furs from Alaska. Lisyansky used the delays to repair the Neva's hull and keel. A conflict between Krusenstern and Lisyansky started in January. Lisyansky wanted to be more involved in the trade and receive a captain's commission.

The presence of the Russian ships in Canton almost caused a political crisis. On January 22, 1806, the governor ordered to stop loading Chinese goods until he received an official response from Beijing. He even placed guards around the ships. Director Drummond helped by contacting the customs manager. The guards were removed. He also wrote to the governor, asking for the ships to be released. The Chinese officials seemed eager to get rid of the Russians quickly. The exit documents were completed in just two days. On February 9, both ships left Guangzhou. After they left, the Jiaqing Emperor canceled all the deals. He ordered the ships to be detained, saying that sea trade with Russia would harm border trade.

At that time, war between France and Russia was expected. So, Krusenstern ordered the ships to stay together. If bad weather separated them, they would meet at Saint Helena island.

Neva Returns Home

The Nadezhda and Neva sailed together until April 15, 1806. On March 5, a sailor died from a stomach illness and was buried at sea. On April 15, the ships separated due to "gloomy weather." Lisyansky, commanding the Neva, decided to sail at full speed to return first. He passed the southern tip of Africa on April 20.

On April 24, Lisyansky decided not to wait for Krusenstern at Saint Helena. He wanted to return to St. Petersburg on his own, as he believed they had enough supplies for three months. He changed the crew's food rations. They ate salted beef, and tea leaves were added to soup. On certain days, they had rice porridge or pickled vegetables.

On April 26, a big argument happened among the officers. Lieutenant Povalishin strongly disagreed with Lisyansky's plans. Lisyansky threatened to send him back to his cabin. To collect rainwater and get help if needed, the route back to St. Petersburg was set along the Cape Verde Islands and then the Azores. On June 9, near Corvo Island, the ship met an English warship. They learned that a war had started between France and Russia. Even though the Neva had safety papers from the French government, the crew prepared for a possible fight.

On June 26, the ship reached the English Channel. A pilot boat guided the ship to Portsmouth. This fast journey took 140 days, which was amazing for that time. No one on board had scurvy. Lisyansky visited London. On July 21, a sailor died from an old injury. On August 5, the Neva sailed at a record speed of 11 knots (about 20.37 kilometers per hour). On the morning of August 6, it anchored in Kronstadt.

Lisyansky had been traveling for almost three years (1095 days). He covered 45,083 nautical miles (83,493 kilometers) in 532 days at sea. For more than half the time and distance, he sailed independently. On August 6, the company manager Korobitsyn reported to the Russian-American Company shareholders. The next day, company directors visited the Neva. On August 8, the emperor visited the ship and had breakfast, praising the sailors' food. On September 5, Alexander I inspected the goods from China. On September 9, the Chinese tea was sold. Korobitsyn received a gold medal. Lisyansky was promoted, received an award, a pension, and a bonus. The crew gave him a golden sword.

Nadezhda Returns Home

Sailing through the South China Sea during typhoon season was dangerous. On March 1, Krakatoa island became visible. The Nadezhda found a safe passage. Leaving the Sunda Strait, the ship struggled with a strong current but was saved by a rising wind. It reached the Indian Ocean on March 3. On March 11, a massive storm damaged the Nadezhda's front mast. On April 15, the Nadezhda separated from the Neva. Krusenstern realized Lisyansky had chosen a different course on purpose. Four days later, Krusenstern rounded the Cape of Good Hope. On May 3, he arrived at Saint Helena island, having traveled from Macau in 79 days.

Lieutenant Levenstern was the first to go ashore. He brought news about the war between Russia and France.

It was hard to get food on Saint Helena. Flour was scarce, and other products were very expensive. For example, a ram cost three guineas, a bag of potatoes cost one guinea, and a chicken or duck cost half a guinea. As a result, the crew had to rely on their own supplies until they reached Copenhagen. Knowing about the war with France, Krusenstern regretted Lisyansky's independent decision. Also, some guns were left in Kamchatka, and the English couldn't replace Russian ammunition. So, with only 12 guns, Krusenstern decided to sail around Scotland through the Orkney islands.

On May 8, the Nadezhda left Jamestown. On May 21, it crossed the Equator for the fourth and last time. On July 17, the ship passed between the islands of Fair Isle and Mainland of the Shetland islands. On July 21, it got closer to the Norwegian coast. On Fair Isle, the crew bought fresh fish, eggs, and lamb. On July 23, the ship met an English frigate, the Quebec. Krusenstern learned that Lisyansky had left Portsmouth a week earlier. The Nadezhda arrived in Copenhagen at 10 AM on August 2. The journey from China took five months and 24 days, with only a four-day stop at Saint Helena. The captain reported no scurvy patients on board. The ship anchored in Kronstadt on August 19, having been away for 3 years and 12 days.

On August 21-22, Admiral Pavel Chichagov and Count Rumyantsev visited the ship. On August 27, Krusenstern was invited to the Kamenny Island Palace. The empress mother, Maria Feodorovna, gave him a diamond snuffbox. On August 30, Emperor Alexander I visited the Nadezhda. All officers received promotions and pensions. Krusenstern also received an award and was made an honorary member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Scientists Horner and Tilesius received pensions. Sailors from both ships received retirement pensions.

Discoveries and Legacy

New Places Found

The crews of the Nadezhda and Neva made several important discoveries in the Pacific Ocean. They explored the last unknown areas in the northern part. Lisyansky and his navigator, Dmitry Kalinin, mapped Kodiak Island in the Gulf of Alaska. They also mapped part of the Alexander Archipelago. Kalinin discovered Kruzof Island, which was thought to be a group of islands. Lisyansky named a large island north of Sitka as Chichagof Island. On the way from Kodiak to Macau, they found an uninhabited island, later named Lisyansky Island, and the Neva reef, both part of the Hawaiian islands. To their southwest, they discovered the Krusenstern reef.

On the way from Japan to Kamchatka, Krusenstern sailed through the Tsushima Strait into the Sea of Japan. He mapped the western coast of Hokkaido. They found a small bay called the Gulf of Patience. Many names they gave, like Capes Senyavin and Soymonov, are still on maps today. While passing through the Greater Kuril Chain, Krusenstern discovered four "Lovushki" islands. He also explored the Northern Strait and named its capes "Elizabeth" and "Maria." Near the northern entrance to the Amur Liman, the water was shallow. Krusenstern concluded that Sakhalin was a peninsula.

The expedition also made many observations about the ocean. They discovered the Equatorial Counter Current in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. They measured temperature differences at depths up to 400 meters and studied water clarity and color. They found out what caused the Milky seas effect (glowing ocean water) and collected data on air pressure and tides.

Sharing the Discoveries

The Krusenstern expedition sparked great interest in Russia and Europe for decades. The collection of cultural items they brought back was first put in a museum. Then, it was sent to the Kunstkamera, a famous museum. This collection included items from Easter Island, the Marquesas, and Hawaii.

The expedition's findings were widely published. From 1809 to 1812, Krusenstern's three-volume Journey Around the World was published in Russian and German. It included an atlas with 32 landscapes and 44 pictures of different people. Later, Krusenstern's book was translated into English, French, Italian, Dutch, Swedish, and Danish.

Lisyansky published his own account of the journey in 1812. It included illustrations and maps. This book was also popular in the West and was published in London in English in 1814. Langsdorf's description was published in German and English but not in Russian. Many diaries and notes from the crew were also published. Some, like the journal of navigator Dmitry Kalinin, were only published in the 21st century.

In 2003, the previously unpublished diary of Levenstern came out in Russian and English. In 2005, a book called Around the World with Krusenstern was published. It included drawings by Tilesius, botanical illustrations by Langsdorf, and other unpublished pictures. In 2015, all of Ratmanov's journals were published, along with watercolor paintings by Horner and Langsdorf.

Remembering the Journey

Historians today continue to study the first Russian circumnavigation. They look at its impact on geography, natural history, and different cultures. New documents have been found, leading to more research on the relationships between the expedition leaders.

Krusenstern and Lisyansky's expedition has also appeared in children's books. In 1930, Nikolai Chukovskii wrote a novel about them. The adventure novel Islands and Captains by Vladislav Krapivin (1984–1987) is also based on this journey. A famous phrase from a Russian cartoon, "Ivan Fedorovich Krusenstern – a person and a steamboat," refers to Krusenstern, even if the characters in the cartoon don't know who he is.

In 1993, the Central Bank of Russia released a series of commemorative coins dedicated to the first Russian circumnavigation. Russia, Estonia, Ukraine, and Saint Helena island have also released postmarks. In December 2013, a four-episode documentary series called Neva and Nadezhda: The first Russian circumnavigation was released on Russian television.

- A series of commemorative coins from the Bank of Russia (1993)

-

Nikolay Rumyantsev, the sponsor, and the English Embankment in Saint Petersburg, the starting point

-

Nadezhda and Ivan Kruzenshtern

Notable Crew Members

- Adam Johann von Krusenstern: Leader of the expedition and Captain of the Nadezhda. He later became a Russian Admiral.

- Yuri Lisyansky: Captain of the Neva. He won the Battle of Sitka against the Tlingit people during the journey.

- Nikolai Rezanov: Appointed ambassador to Japan. He co-led the expedition with Krusenstern until Kamchatka. He was one of the founders of the Russian-American Company in 1799.

- Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen: A lieutenant and cartographer. He later discovered the continent of Antarctica during his own journey around the world. He became a Russian Admiral.

- Otto von Kotzebue: Started as a cabin boy. He later led two more trips around the world. He discovered over 400 Pacific islands and the Kotzebue Sound in Alaska.

- Fyodor Ivanovich Tolstoy: A count and a lively participant. He became known as "the American" and was a model for a character in Pushkin's famous book Eugene Onegin.

- Grigory Langsdorff: A naturalist and physician. He later became a famous Russian explorer of Brazil and South America.

- Wilhelm Gottlieb Tilesius von Tilenau: The ship's doctor, a marine biologist, and the expedition artist. His illustrated report on the journey was published in 1814.

See also

In Spanish: Primera circunnavegación rusa para niños

In Spanish: Primera circunnavegación rusa para niños