History of Alberta facts for kids

The land that is now Alberta, Canada, has a long and interesting history, going back thousands of years. We know about its written history from when Europeans first arrived. The rich soil was perfect for growing wheat, and the huge prairie grasslands were great for raising cattle.

When railroads came in the late 1800s, many farmers and cattleman from Eastern Canada, the United States, and Europe moved here. Wheat and cattle are still important today, but farms are much bigger, and fewer people live in rural areas. Alberta has grown into a place with many cities, and its economy now includes exporting petroleum (oil) as well as wheat and cattle.

Contents

First Peoples of Alberta

The first people in Alberta, the ancestors of today's First Nations in Alberta, arrived at least 8,000 years BC. Scientists believe they came across a land bridge from Asia.

Southern tribes, like the Plain Indians such as the Blackfoot, Blood, and Peigans, learned to hunt Plains Bison. At first, they hunted without horses, but later they used horses that Europeans brought. Northern tribes, like the Woodland Cree and the Chipewyan, hunted, trapped, and fished in the aspen parkland and boreal forest areas.

Later, a new group called the Métis formed. They were a mix of these First Peoples and French fur traders. Many Métis moved to Alberta after being displaced from areas to the east.

How First Peoples Organized Themselves

When Europeans arrived, they started to record the history of the nations that would later become Alberta. We can also learn about earlier times from stories passed down through generations and from old artifacts.

Some parts of the Great Plains might have been empty for a long time due to a big drought around 950–1250 AD. When the rain returned, people from many different language groups and parts of North America moved in. For example, some groups like the Comanche and Shoshoni came from the southwest. Algonquian speakers like the Plains Cree and Blackfoot came from the northeast. The Siouxan peoples, including the Assiniboine and Nakoda, came from the southeast. There were also groups like the Tsuu T'ina from the far northwest.

Groups and Alliances

The smallest group for both Plains and Subarctic peoples was called a "lodge." This was usually an extended family or a close group that lived together in a teepee or other home. Several lodges would travel together in a "band." For the Blackfoot, a band might have 10 to 30 lodges, which meant about 80 to 240 people. Bands were important for hunting and fighting. They could form and break apart depending on what was happening.

People also belonged to other groups, like a clan (based on family ties), a tribe (sharing a language and beliefs), or a ritual society (based on age or rank).

Plains bands could gather in large groups for hunting or war, especially after they had horses. This was because there was plenty of bison for food and the land was open and easy to travel. They could also move long distances. Subarctic peoples also moved around, but in smaller groups, as the northern forests couldn't support large numbers of people in one place for long.

When historians talk about groups on the Great Plains, they often mention "inter-tribal warfare." But decisions were not always based on just one tribe's identity. Often, bands from different tribes would form alliances, called a confederacy. The history of the Great Plains before settlement was about these large confederacies, made up of many bands from different tribes, constantly changing their members.

Early Recorded History

We get our first look at alliances in the region from the journal of Henry Kelsey around 1690-1692. He wrote that the Iron Confederacy (Cree and Assiniboine) were friends with the Blackfoot Confederacy (Peigan, Kainai, and Siksika). They were allied against other groups whose names are not fully known.

Another early story comes from Saukamappe, a Cree man adopted by the Peigan. He told explorer David Thompson about his early life in the 1780s. French explorer Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye reached the upper Missouri River in 1738.

From these stories, we can see a general picture of the northern Great Plains in the 1700s. The Shoshone, who got horses early, became very powerful. By the early 1700s, they hunted from the North Saskatchewan River (in present-day Alberta) down to Wyoming. They were known for taking war prisoners, which made other groups dislike them. This led to a temporary alliance between the Blackfoot Confederacy, Sarsis, Plains Crees, Assiniboines, and Gros Ventres to resist the Shoshone.

However, the Shoshone could not keep horses to themselves. The Blackfoot soon got their own through trade, raids, or breeding. At the same time, the Blackfoot started getting guns from the British Hudson’s Bay Company through Cree and Assiniboine traders. By 1780, the Peigans and other Blackfoot groups pushed the Shoshone south of the Red Deer River.

A smallpox outbreak in 1780-1782 greatly affected both the Shoshone and Blackfoot. But the Blackfoot used their new military strength to raid the Shoshone. They welcomed many Shoshone women and children into their own communities, which helped increase their numbers. By 1787, the Blackfoot had taken over Shoshone territory. The Shoshone moved west or far south. The Blackfoot then controlled an area from the North Saskatchewan River in the north to the upper Missouri River in the south, stretching about 300 miles east from the Rocky Mountains.

But the Blackfoot's control of horses and hunting grounds was not secure. From the northeast, the Iron Confederacy (Cree and Assiniboine, among others) were losing their role as traders. The Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company moved further inland. These groups then started hunting bison on horseback in the same areas the Blackfoot had just taken from the Shoshone.

Before Alberta Became a Province

The first European to reach Alberta was likely a Frenchman like Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye or his sons. They traveled inland to Manitoba in the 1730s, setting up forts and trading furs directly with First Peoples. French fur traders likely met the Blackfoot-speaking people of Alberta. The Blackfoot word for "Frenchman" means "real white man." By the mid-1700s, the French were getting most of the best furs before they could reach the Hudson's Bay trading posts, causing tension between the companies.

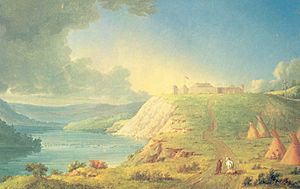

The first written account of Alberta comes from fur trader Anthony Henday. He explored near present-day Red Deer and Edmonton in 1754–55. He spent a winter with a Blackfoot group, trading and hunting buffalo. Other important early explorers included Peter Fidler, David Thompson, Peter Pond, Alexander MacKenzie, and George Simpson. The first European settlement was founded at Fort Chipewyan by MacKenzie in 1788. Fort Vermilion also claims to have been founded in 1788.

Early Alberta history is closely linked to the fur trade and the competition it caused. At first, there was a struggle between English and French trading companies. Most of central and southern Alberta is part of the Hudson Bay watershed. In 1670, the English Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) claimed this area as part of its monopoly territory, Rupert's Land. French traders from Montreal, known as Coureurs des bois, challenged this. After France lost power in North America in 1759, the British HBC had full control of the fur trade.

But this was soon challenged in the 1770s by the North West Company (NWC). This private company from Montreal wanted to restart the old French trading network in areas that didn't drain into Hudson Bay, like the Mackenzie River, and areas draining to the Pacific Ocean. Many of Alberta’s cities and towns started as either HBC or NWC trading posts, including Fort Edmonton. The HBC and NWC eventually joined together in 1821. In 1870, the new HBC's trade monopoly ended, and anyone could trade in the region. The company gave Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory to the Dominion of Canada as the Northwest Territories.

While the fur trade was an economic struggle, there was also a spiritual one between Christian churches trying to convert First Peoples. The first Roman Catholic missionary, Jean-Baptiste Thibault, arrived at Lac Sainte Anne in 1842. The Methodist Robert Rundle arrived in 1840 and started a mission in 1847.

In 1864, the Roman Catholic Church in Canada asked Father Albert Lacombe to work with the Plains Indians, and he had some success. Several Alberta towns were first settled due to French missionary work, such as St. Albert and St. Paul. The Anglican Church of Canada and other Protestant groups also sent missions to First Peoples.

The area that became Alberta was acquired by Canada in 1870. The government hoped it would become a farming area for white Canadians. To prepare the land for settlement, the government began negotiating the Numbered Treaties with various First Nations. These treaties offered them reserved lands and government support. In return, the First Nations gave up their claims to most of the land.

At the same time, the decline of the HBC's power allowed American traders and hunters to move into southern Alberta. This changed the First Peoples' way of life. A major concern was Fort Whoop-Up near present-day Lethbridge, and a violent event called the Cypress Hills Massacre in 1873.

As the bison disappeared from the Canadian west, cattle ranches started to take their place. Ranchers were among the first successful settlers. The dry prairies and foothills were good for American-style, open-range ranching. Black American cowboy John Ware brought the first cattle into the province in 1876.

To bring law and order to the West, the government created the North-West Mounted Police, known as the "mounties," in 1873. In July 1874, 275 officers began their famous "march west" to Alberta. They set up a new headquarters at Fort Macleod. The next year, new outposts were founded: Fort Walsh in the Cypress Hills, and Fort Calgary, which later became the city of Calgary.

The peace and stability brought by the Mounties encouraged dreams of many people settling on the Canadian Prairies. The land was surveyed by the Canadian Pacific Railway for possible routes to the Pacific. The early favorite was a northern line through Edmonton and the Yellowhead Pass. But the success of the Mounties in the South, along with the government's wish to claim Canadian control of that area, led the CPR to change its route at the last minute. It chose a more southern path through Calgary and the Kicking Horse Pass. Some surveyors had warned that the south was a dry area not good for farming.

In 1882, the District of Alberta was created as part of the Northwest Territories. It was named after Princess Louise Caroline Alberta, Queen Victoria's fourth daughter. She was married to the Marquess of Lorne, who was Canada's Governor General at the time.

Settlement of the Land

The CPR railway was almost finished in 1885 when the North-West Rebellion, led by Louis Riel, began. This conflict involved Metis and First Nations groups against the Canadian government. The rebellion spread across what is now Saskatchewan and Alberta. After a Cree group attacked a white settlement at Frog Lake (now in Alberta), Canadian militia from Ontario were sent by the CPR to the District of Alberta and fought the rebels. The rebels were defeated, and Riel was captured.

After the 1885 rebellion ended, settlers started to move into Alberta. The closing of the American frontier around 1890 led 600,000 Americans to move to Saskatchewan and Alberta. Farming grew rapidly from 1897 to 1914.

The railways created town sites about six to ten miles apart. Lumber companies and investors loaned money to encourage building on these lots. Immigrants faced a new and tough environment. Building a home, clearing and farming thirty acres, and fencing the property were all requirements for homesteaders to own their new land. These were difficult tasks in the valleys shaped by glaciers.

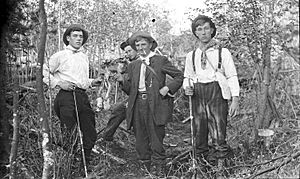

New Settlers Arrive

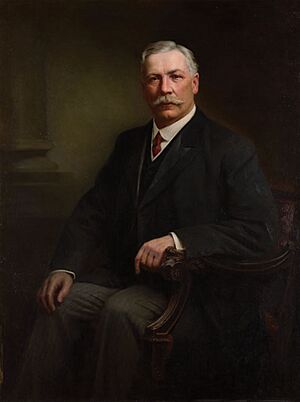

At first, the government preferred English-speaking settlers from Eastern Canada or Great Britain, and some from the United States. But to speed up settlement, the government, led by Minister of the Interior Clifford Sifton, soon started inviting settlers from Europe. Many Germans, Ukrainians, and Scandinavians moved in. They often settled in separate ethnic groups, giving parts of Alberta unique cultural areas.

Some historians suggest that the large number of immigrants from the United States brought ideas like freedom, individualism, and equality, which were different from traditional English Canadian ideas. This led to the growth of new political groups.

Norwegian Settlements

One example of a settlement was by Norwegians from Minnesota. In 1894, Norwegian farmers from Minnesota, who were originally from Bardu, Norway, settled on Amisk Creek south of Beaverhill Lake, Alberta. They named their new settlement Bardo, after their homeland. Canada wanted to create planned immigrant colonies with single nationalities in the Western Provinces. The Bardo settlement grew steadily, and from 1900 on, most settlers came directly from Bardu, Norway, joining family and old neighbors. Living conditions were simple for many years, but the settlers quickly built churches, schools, and social groups.

Welsh Workers

In July 1897, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) started building a railway through Crow's Nest Pass, Alberta. To attract a thousand workers from Wales, the British government offered them $1.50 a day and land. This offer was advertised by shipping companies and newspapers. Many workers from Bangor, North Wales, where quarrymen had been on strike, were interested. However, the travel costs were too high for many, so fewer than 150 people came. By November, letters arrived in Wales complaining about the living and working conditions in the CPR camps. Government officials tried to downplay these criticisms. Although some immigrants found success in Canada, the plan was canceled in 1898.

Mormon Communities

About 3,200 Mormons came from Utah, where their practice of polygamy had been made illegal. They were very focused on their community and set up 17 farm settlements. They were pioneers in irrigation techniques. They thrived, and in 1923, they opened the Cardston Alberta Temple in their main town of Cardston. Today, about 50,000 Mormons live in Alberta.

Becoming a Province

At the start of the 1900s, Alberta was just a district of the North-West Territories. Local leaders worked hard for it to become a province. The premier of the territories, Sir Frederick Haultain, strongly supported provincehood for the West. However, he wanted one very large province called Province of Buffalo, not the two provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan that were eventually created. Other ideas included three provinces, or two provinces with an east-west border instead of north-south.

The prime minister at the time, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, did not want one province to become too powerful and rival Quebec and Ontario. But he also thought three provinces were not practical, so he chose the two-province plan. Alberta became a province along with Saskatchewan on September 1, 1905.

Many expected Haultain to be appointed as the first Premier of Alberta. However, Haultain was a Conservative, and Laurier was a Liberal. Laurier chose to have Lieutenant Governor George H. V. Bulyea appoint the Liberal Alexander Rutherford as premier.

Another important leader in Alberta at the time was Frank Oliver. He started Edmonton's influential Bulletin newspaper in 1880. He was critical of some government policies in the West. He was elected to the territorial assembly but later became a federal Member of Parliament. He was in charge of drawing the boundaries for the provincial voting areas for the 1905 Alberta elections. Some people accuse him of drawing the boundaries to favor Liberal Edmonton over Conservative Calgary.

Together, Oliver and Rutherford made sure that Edmonton became Alberta's capital.

Early 1900s

The new province of Alberta had 78,000 people but lacked basic services like roads and buildings. Most people were farmers, and they needed schools and medical facilities. The federal government in Ottawa kept control of Alberta's natural resources until 1930. This made economic development difficult and caused problems between the province and the federal government, especially after 1970 when battles over oil became very intense.

Politics in Early Alberta

The Liberals formed Alberta's first government and stayed in power until 1921. After the 1905 election, Premier Alexander C. Rutherford's government began building government services, especially for legal and city matters. Rutherford was a kind leader who supported education. He pushed for a provincial university. Calgary was upset when Edmonton was chosen as the capital, and this anger grew in 1906 when the University of Alberta was given to Strathcona (a suburb that joined Edmonton in 1912).

Communication improved when a telephone system was set up for towns and cities. Long-term economic growth was boosted by building two more transcontinental railroads through Edmonton. These railroads mainly brought people in and shipped wheat out. Attracted by cheap farmland and high wheat prices, immigration reached record levels. Alberta's population reached 470,000 by 1914.

Farmers' Movements

Farmers felt unfairly treated by the railroads and grain elevators. Strong farm organizations appeared, like the United Farmers of Alberta (UFA), formed in 1909. The UFA, guided by William Irvine and later Henry Wise Wood, was first meant to represent farmers' economic interests, not to be a political party. But farmers were unhappy with Liberal provincial policies and Conservative federal policies. Along with falling wheat prices and a railroad scandal, this pushed farmers to get directly involved in politics. They elected three Farmer-oriented members to the provincial legislature and one to federal parliament between 1917 and 1921. This opened the door for them to seek power in 1921.

The UFA won a huge victory in the provincial legislature in 1921. Alberta also strongly supported UFA and Labour candidates in the 1921 federal election. The elected Members of Parliament worked with the Progressive Party of Canada, a national farm organization. Together, they held the balance of power for the minority Liberal and Conservative governments in the 1920s.

John E. Brownlee led the UFA to a second majority government in the 1926 election. During his time as premier, the UFA government ended prohibition (the ban on alcohol). They replaced it with government-controlled liquor sales and regulated private bars. They also passed a Debt Adjustment Act to help farmers in debt and aided workers with fair wage laws. The government also helped the struggling Alberta Wheat Pool in 1929.

A major achievement for Brownlee's government came after long talks with the federal government about Alberta's natural resources. In 1930, control of these resources was given to the province. Brownlee led the UFA to a third majority government in the 1930 election, just before the full effects of the Great Depression hit. As he moved to more conservative financial policies, he lost support from socialists and labor groups.

In 1935, the UFA lost political power. This was partly because the government could not raise wheat prices or lessen the effects of the Great Depression in Canada. A long drought in the southern two-thirds of the province led to poor harvests. Thousands of farms were abandoned or lost due to debt. Farmers were open to new ideas about banking and money reform. The UFA leaders were hesitant about these ideas, so farmers turned to Aberhart's Social Credit movement. They saw it as a way to fight against what they viewed as greedy bankers and debt collectors.

After their defeat, the UFA went back to its original purpose: a chain of co-operative farm-supply stores and a lobby group for farmers.

Healthcare and Nursing

Early homesteaders relied on themselves and their neighbors for medical help. There were few doctors. Pioneer women used traditional remedies. This reliance on home remedies continued even as trained nurses and doctors became more common in the early 1900s. After 1900, medicine, especially nursing, became more organized, particularly in cities.

The Lethbridge Nursing Mission in Alberta was a good example of a Canadian volunteer mission. It was started in 1909 by Jessie Turnbull Robinson, a former nurse. She was elected president of the Lethbridge Relief Society and began nursing services for poor women and children. The mission was run by a volunteer board of women and raised money through donations and payments from an insurance company. The mission also combined social work with nursing, helping to distribute unemployment relief.

Historians have studied the differences between the Alberta Association of Graduate Nurses (AAGN), formed in 1916, and the United Farm Women of Alberta (UFWA), formed in 1915. They disagreed about whether midwifery (helping with childbirth) should be a recognized part of nursing. The AAGN was accused of ignoring the medical needs of rural Alberta women. The UFWA leaders worked to improve the lives of women farmers. Irene Parlby, the UFWA's first president, pushed for a provincial Department of Public Health, government-provided hospitals and doctors, and a law allowing nurses to become certified midwives.

The AAGN leadership opposed midwife certification, saying that nursing training didn't include enough study for midwifery. In 1919, the AAGN and UFWA reached a compromise. They worked together to pass the Public Health Nurses Act, which allowed nurses to serve as midwives in areas without doctors. So, Alberta's District Nursing Service, created in 1919 to coordinate women's health resources, was mainly due to the organized efforts of UFWA members.

The Alberta District Nursing Service provided healthcare in mostly rural and poor areas of Alberta in the first half of the 1900s. It was founded in 1919 by the United Farm Women of Alberta (UFWA) to meet the needs of mothers and emergencies. Nurses provided prenatal care, worked as midwives, performed minor surgeries, checked schoolchildren's health, and ran immunization programs. After World War II, the discovery of large oil and gas reserves brought wealth and more local medical services. When provincial health and universal hospital insurance were introduced in 1957, the District Nursing Service was gradually phased out by 1976.

First Nations Healthcare

Because healthcare was not fully covered by treaties with the Canadian government, First Nations people living on reserves in the early 1900s often received medical care from private groups. The Anglican Church Missionary Society ran hospitals for the Blackfoot groups in southern Alberta. In the 1920s, the Canadian government provided funds to build hospitals on both the Blackfoot and Blood reserves. These hospitals focused on treating tuberculosis with long-term care.

There was a strong connection between federal First Nations healthcare and the idea of social reform in Canada between the 1890s and 1930. During this time, the Department of Indian Affairs became more involved in First Nations health. The federal government built hospitals on reserves and created a system of medical officers to staff them. Before World War II, this healthcare system was often run by missionaries and later taken over by the Department of Indian Affairs. It was a widespread but decentralized system. The services provided were based on Canadian middle-class values and aimed to apply these values to First Nations communities. It seems that people were sometimes hesitant to use these facilities. This shows that the federal government was gradually developing a First Nations health policy and system, contrary to the idea that they refused responsibility before World War II.

Culture and Identity

Becoming Canadian

Most European immigrants were expected to become part of Canadian culture. A key sign of this was speaking English. Children of all immigrant groups strongly preferred speaking English, no matter what language their parents spoke. From 1900 to 1930, the government faced the big job of turning people from many different ethnic and language backgrounds into loyal Canadians. Many officials believed that children learning English would be key to this. However, some immigrant leaders opposed direct English teaching methods. Playing games in English often worked well. Elementary schools, especially in rural Alberta, played a central role in helping immigrants and their children adapt.

Protestant Groups

Between the two World Wars, various Protestant women's missionary societies in Alberta worked hard to keep traditional Anglo-Protestant family and moral values strong. These societies, which included many mainstream church groups and had over five thousand members, actively tried to "Christianize and Canadianize" the large numbers of Ukrainian immigrants in the province. They focused especially on educating children, using music to attract them. Some groups even allowed male members. This movement faded as society became less religious and a more conservative religious movement grew stronger.

In the early 1900s, Methodist religious revivals in Calgary promoted progress and respectability as much as spiritual renewal. In 1908, the Central Methodist Church hosted American evangelists who attracted large crowds. However, few people became church members after the revival. Working-class attendees might have felt uncomfortable among the wealthier and better-dressed people. The church leaders had strong ties to local businesses but did little to reach out to the working class.

The ban on alcoholic drinks was a big political issue, with English-speaking Protestants often against most other ethnic groups. The Alberta Temperance and Moral Reform League, founded in 1907, was based in Methodist and other Protestant churches. They used anti-German themes to help pass laws that banned alcohol in July 1916. These laws were repealed in 1926.

Catholic Groups

The Catholic archbishop of Edmonton, Henry Joseph O'Leary, greatly influenced the city's Catholic communities. His efforts show many challenges the Catholic Church faced then. In the 1920s, O'Leary favored his fellow Irish and reduced the influence of French Catholic clergy in his archdiocese, replacing them with English-speaking priests. He helped Ukrainian Catholic immigrants adapt to stricter Roman Catholic traditions. He also supported Edmonton's separate Catholic school system and established a Catholic college at the University of Alberta and a seminary in Edmonton.

French-Speaking Communities

In 1892, Alberta adopted the Ontario school system. This system focused on government-run schools that promoted the English language, history, and customs. Mostly French-speaking communities in Alberta kept some control of local schools by electing trustees who supported French language and culture. Groups like the Association Canadienne-Française de l'Alberta expected trustees to follow their cultural goals. Another problem for French-speaking communities was the constant shortage of qualified French-speaking teachers from 1908 to 1935. Most of these teachers left their jobs after only a few years. After 1940, school consolidation largely ignored the language and culture issues of French speakers.

Ukrainian Communities

A major debate about the language rights of ethnic minorities in western Canada was the 1913 Ruthenian School Revolt in the Edmonton area. Ukrainian immigrants, sometimes called "Galicians" or "Ruthenians," settled near Edmonton. The Ukrainian community tried to use the Liberal Party to gain political power in mostly Ukrainian areas and introduce bilingual education. However, party leaders stopped this, blaming a group of teachers for the idea. As a result, these teachers were called "unqualified." The actions by Ukrainian residents of the Bukowina school district did not prevent the dismissal of Ukrainian teachers. By 1915, it was clear that bilingual education would not be allowed in early 1900s Alberta.

Italian Communities

Italians arrived in two main waves: the first from 1900 to 1914, and the second after the Second World War. The first arrivals came as temporary workers, often returning to southern Italy after a few years. Others became permanent city residents, especially when World War I prevented international travel. From the start, they began to influence the cultural and business life of the area. As "Little Italy" grew, it provided important services for its members, such as a consul and the Order of the Sons of Italy. Initially, Italians lived peacefully with their neighbors. However, during World War II, they faced prejudice and discrimination.

Rural Life

An economic crisis hit much of rural Alberta in the early 1920s. Wheat prices dropped sharply from their wartime highs, and farmers found themselves deeply in debt.

Farms and Wheat

Wheat was the main crop. The tall grain elevator next to the railway tracks became a key part of Alberta's grain trade after 1890. It helped "King Wheat" become dominant in the region by connecting the province's economy with the rest of Canada. Grain elevators efficiently loaded grain into railroad cars. They were often grouped together in "lines," and their ownership became concentrated in fewer companies, many controlled by Americans. The main businesses involved were the Canadian Pacific Railway and powerful grain groups.

Many newcomers were not familiar with the dry farming techniques needed for wheat. So, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) set up a demonstration farm at Strathmore in 1908. It sold irrigated land and advised settlers on the best farming and irrigation methods. Big changes in the Alberta grain trade happened in the 1940s, especially the merging of grain elevator companies.

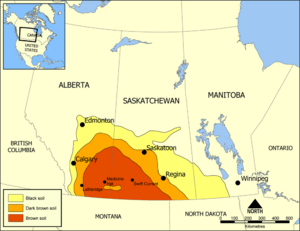

Some historians suggest that recklessness, greed, and too much optimism played a part in the early 1900s financial crisis on the Canadian wheat frontier. Starting in 1916, the Palliser Triangle, a dry region in Alberta and Saskatchewan, suffered a decade of dry years and crop failures. This led to financial ruin for many wheat farmers. Overconfidence from farmers, investors, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and the Canadian government led to land investments and development in the Palliser on a huge and risky scale. Much of this expansion was funded by mortgage and loan companies in Britain eager to invest overseas.

British money managers were influenced by global economic forces, including fewer investment opportunities in Britain, extra capital, and massive investment expansion on the Canadian frontier. Less grain production in Europe and more in the Prairie Provinces also encouraged money to be sent from London. The idea that the Palliser was a rich region, combined with growing faith in technology, created a false sense of security. Between 1908 and 1913, British firms lent huge amounts to Canadian farmers to plant their wheat crops. Only when the drought began in 1916 did it become clear that too much credit had been given out.

Ranches and Mixed Farming

The term "mixed farming" better describes southern Alberta's farming practices from 1881 to 1914 than "ranching." "Pure ranching" involved cowboys working mostly from horseback, which was common when huge ranches formed in 1881. But practices quickly changed. Hay was planted and cut in summer for winter cattle feed. Fences were built to keep winter herds contained. Dairy cows and barnyard animals were kept for personal use and to sell. Mixed farming was clearly the main type of farming in southern Alberta by 1900.

Captain Charles Augustus Lyndon and his wife, Margaret, started one of Alberta's first ranches in 1881. They settled in the Porcupine Hills west of Fort Macleod. They mainly raised cattle but also horses for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police for extra income. Lyndon's herds suffered during the harsh winter of 1886-87. He developed an irrigation system and a post office as the area grew in the 1890s. Although Lyndon died in 1903, his family kept his businesses going until 1966 when the ranch was sold.

The survival of Alberta's cattle industry was uncertain for much of the late 1800s and early 1900s. At two points, 1887–1900 and 1914–20, the industry was very prosperous. The later boom began when the United States passed a law in 1913 that allowed Canadian cattle to enter freely. Exporting Alberta cattle to Chicago markets was very profitable for the highest quality livestock. By 1915, most cattle from the Winnipeg stockyards were exported to the United States, which hurt Canada's own beef market. Several things, including the severe winter of 1919-20, the end of high wartime beef prices, and the US putting tariffs back on Canadian cattle, all caused the Alberta cattle market to collapse. The boom ultimately worked against Alberta's economic interests because the high prices made it too expensive to finish cattle locally.

Some ranchers became important business people. Alfred Ernest Cross (1861–1932), a rancher and brewer in Calgary with interests in gas, electricity, and oil, was a key figure in modernizing Alberta and the Canadian West. He represents the spirit of enterprise, profit-seeking, family-focused business, and economic growth through reinvesting earnings. His family managed his businesses, which are still important in Alberta's economy today. Cross is mainly remembered for his improvements in cattle breeding and his scientific approach to brewing.

Women on Farms

Gender roles were very clear. Men were mainly responsible for clearing land, planting and harvesting, building houses, buying and fixing machinery, and handling money. At first, there were many single men on the prairie, or husbands whose wives were still back east. They found it hard and realized they needed a wife. As the population grew quickly, wives played a central role in settling the prairie region. Their hard work, skills, and ability to adapt to the tough environment were crucial. They cooked, mended clothes, raised children, cleaned, tended gardens, helped with harvest, and nursed everyone. Even though laws and economic ideas often overlooked women's contributions, their flexibility in doing both productive and household labor was vital for family farms to survive and for the wheat economy to succeed.

Miners

James Moodie developed the Rosedale Mine in Alberta's Red Deer River Valley in 1911. Even though Moodie paid higher wages and ran the mine more safely and efficiently than other coal mines, the Rosedale mine still had work slowdowns and strikes. Some radical workers saw Moodie as an oppressor because he owned the mine and provided services for the camp. The radicalism at the mine decreased as Moodie replaced immigrant miners with Canadian military veterans who appreciated the safe work environment.

City Life

In larger cities, the Alberta chapter of the Canadian Red Cross provided help to the community during the difficult years of the 1920s and 1930s. It also successfully pushed the government to take a more active role in helping people during hard times. Every town had people who dreamed big, but most towns remained small villages. For example, Bow City seemed promising because of its coal and good grazing land. Lumber merchants formed a company and sold real estate to investors. But bad luck, like a drought during World War I, ruined these ambitions.

Business in Cities

Most businesses were family-run, with few large operations apart from the railways. In 1886, the Cowdry brothers (Nathaniel and John) opened a private bank at Fort Macleod. Their story shows how a small private bank became important in early southwestern Alberta finance. Both brothers were smart businessmen and community leaders. The banking business grew, opening branches and widely advertising and lending money. In March 1905, the Cowdrys sold their bank in Fort Macleod to the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. Family businesses in private banking were crucial in providing credit to southwestern Alberta and helping the modern economy grow.

After a big economic boom during World War I, a sharp, short depression hit Alberta in 1920-22. Conditions were typical in the town of Red Deer, a railway and trading center between Calgary and Edmonton that depended on farmers. The hardship in the early 1920s was as bad, or even worse, than during the longer Great Depression of the 1930s. The economic problems had started as early as 1913, when the speculative boom that had driven Alberta's prosperity collapsed. But World War I in 1914 created a huge demand for farm products, which hid the serious weaknesses of the provincial economy. After the war, however, unemployment soared as veterans returned, and inflation increased. Grain prices began to fall in 1920, causing more difficulties. By spring 1921, many Red Deer businesses had gone bankrupt, and the city's unemployment rate was estimated at 20%. The city's economy began to improve in 1923, and Red Deer officials could finally collect enough tax money to avoid needing short-term bank loans.

Women in Cities

The Calgary Current Events Club, started in 1927 by seven women, quickly became popular with professional women in the city. In 1929, the group changed its name to the Calgary Business and Professional Women's Club (BPW) to join a national federation of such groups. Members traveled to London, England, in 1929 to argue for women to be recognized as full legal citizens. In the 1930s, the group discussed many important political issues of the day. These included a minimum wage, fair unemployment insurance, required medical exams for schoolchildren, and a medical certificate for marriage. The national BPW convention was held in Calgary in 1935. The club actively supported Canadian forces overseas in World War II. At first, most members were secretaries and office workers. More recently, it has been led by executives and professionals. The organization continues to work on women's economic and social issues.

Cinema and Movies

Movies have been an important part of city culture since 1910. The places where people watched films, from small nickelodeons to large multiplexes, have changed in ways that reflect changes in society. Cinemas in Edmonton showed the changing city landscape. Because movie theaters themselves are part of the entertainment, the cinema industry constantly builds, renovates, and tears down buildings. The industry is always changing to attract people inside. Edmonton's cinemas have moved with retail stores from downtown to suburban shopping malls. Just as Edmonton is known for its many stores, it also has one of the highest numbers of movie screens in Canada compared to its population. Cinemas are a good way to see trends in city development.

Sports and Recreation

Across the province, popular sports included skiing and skating for everyone, and hunting and fishing for men and boys.

Competitive sports grew in cities, especially hockey. It provided a way for cities to compete, like Edmonton and its neighbor Strathcona in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Edmonton, on the north bank of the Saskatchewan River, and Strathcona, on the south bank, developed separately because travel and communication across the river were limited. (They merged in 1912.) Besides offering an outlet for city rivalries, games between the Edmonton Thistle and Strathcona Shamrock hockey clubs brought together people from different social classes and backgrounds to support their team.

Skiing began in Banff in the 1890s and gained popularity with the winter carnival in 1916. In the following decades, the carnival became famous. Ski jumping and cross-country races brought a lot of attention. By 1940, Banff had become one of Canada's leading skiing centers and was heavily promoted as a vacation spot by the Canadian Pacific railway.

Oil, Gas, and Oil Sands

Alberta has played a central role in Canada's petroleum industry. This includes the discovery and development of conventional oil and natural gas. It also includes the development of the world's largest bitumen deposits in the province's huge northern oil sands. Alberta became one of the world's top producers of crude oil and natural gas. This generated billions of dollars for the province and caused a strong disagreement with the national government.

The first oil field in western Canada was Turner Valley, south of Calgary. Large amounts of oil were found there at a depth of about 3,000 feet (910 meters). Calgary became the oil capital, known for its bold business spirit. For a time, Turner Valley was the largest oil and gas producer in the British Empire. Three different discovery phases marked the field's history. In 1931, the province passed the Oil and Gas Wells Act to reduce the waste of natural gas. In 1938, the Alberta Petroleum and Natural Gas Conservation Board was successfully created. It put in place measures to conserve resources and share production fairly. The goal was to maximize long-term output and protect small producers.

In 1947, an even bigger field opened at Leduc, 20 miles (32 km) south of Edmonton. In 1948, oil mining began at Redwater. Both these fields were surpassed in importance in 1956 with the discovery of the Pembina field west of Edmonton. Other fields were found east of Grande Prairie and in central Alberta. From collection points near Edmonton, the oil is sent by pipeline to refineries. Some are as far away as Sarnia, Toronto, and Montreal to the east, Vancouver to the west, and especially the U.S. to the South. Interprovincial Pipe Line (IPL) started in 1949, transporting oil to refineries in the east. IPL became Enbridge Pipelines in 1998 and now has 4500 employees. It moves 2 million barrels a day over 13,500 miles of pipe.

Alberta produced 81% of Canada's crude oil in 1991, when Alberta's traditional oil fields reached their peak. Output is now slowly declining. Before the 1970s, major oil producers were controlled by large U.S. oil companies.

Natural Gas

Searching for oil led to the discovery of large natural gas reserves. The most important gas fields are at Pincher Creek in the southeast, at Medicine Hat, and in the northwest. The TransCanada pipeline, completed in 1958, carries some of the gas eastward to Ontario and Quebec. Other pipelines run to California. Alberta produces 81% of Canada's natural gas. An early pioneer in discovering and using natural gas was Georg Naumann.

Oil Sands Development

The "oil sands" or "tar sands" in the Athabasca River valley north of Fort McMurray hold a huge amount of oil. It is one of the world's richest deposits, second only to Saudi Arabia. The first plant to extract oil from the tar sands was finished in 1967, and a second plant was completed in 1978. In 1991, these plants produced about 100 million barrels of oil. Expansion was rapid, with highly paid workers flown in from eastern Canada, especially from areas like the Maritimes and Newfoundland. In 2006, bitumen production averaged 1.25 million barrels per day (200,000 m3/d) from 81 oil sands projects. This represented 47% of Canada's total oil output. However, processing bitumen releases large amounts of carbon dioxide, which concerns environmentalists worried about global warming.

In the 1960s, Great Canadian Oil Sands, Ltd., a small Canadian company, used new technology and large investments to pioneer oil sand extraction in the Athabascan region. Unfavorable leasing terms from the provincial government and the high financial risk forced the company to find an investment partner. The large American oil company Sun Oil Company took the risk. As the investment burden on Sun increased, the company had to take financial and managerial control of the operation. So, the Canadian company had to give up its independence to pursue this complex industrial project. In 1995, Sun sold its interest to Suncor Energy, based in Calgary. Suncor is second to Syncrude in the oil sands, but Syncrude is controlled by a group of international oil companies.

Related Industries

Alberta's oil and natural gas provide raw materials for large industrial complexes in Edmonton and Calgary. There are also smaller ones in Lethbridge and Medicine Hat. These complexes include oil and gas refineries and plants that use refinery by-products to make plastics, chemicals, and fertilizer. The oil and gas industry also creates a market for companies that supply pipes, drills, and other equipment. Large amounts of sulfur are extracted from natural gas in plants near the gas fields. Helium is extracted from the gas in a plant near Edson, west of Edmonton.

Social Credit Movement

Social Credit (often called Socred) was a popular political movement that was strongest in Alberta and nearby British Columbia from the 1930s to the 1970s. Social Credit was based on the economic ideas of an Englishman named C. H. Douglas. His ideas, first brought to public attention in Alberta by UFA and Labour Members of Parliament in the early 1920s, became very popular across the nation in the early 1930s. A main idea was the free distribution of prosperity certificates, which opponents called "funny money."

During the Great Depression in Canada, the demand for big changes peaked around 1934, after the worst part was over and the economy was getting better. Mortgage debt was a big problem because many farmers could not make their payments and faced losing their farms to banks. Although the UFA government passed laws to protect farm families from losing their homes, many farm families lived in poverty and faced losing the land they needed to run profitable farms. Their insecurity was a strong reason for a feeling of political desperation. The farmers' government, the UFA, was confused by the depression, and Albertans demanded new leadership.

Prairie farmers had always believed that they were being taken advantage of by Toronto and Montreal. They needed a leader who would promise to overcome the existing economic and legal barriers to fight for Social Credit. The Social Credit movement in Alberta found its leader in 1932 when William Aberhart read his first Social Credit book. It became a political party in 1935 and spread quickly. It was elected to a majority government on August 22, 1935.

The new premier was radio evangelist William Aberhart (1878–1943). He preached about biblical prophecy. Aberhart was a fundamentalist, preaching God's word and quoting the Bible to find solutions for the problems of the modern world. He believed the capitalist economy was flawed because it produced goods but didn't give people enough money to buy them. He said this could be fixed by giving out money as "social credit," or $25 a month for every man and woman. He promised this would bring back prosperity to the 1600 Social Credit clubs he formed in the province.

Alberta's business people, professionals, newspaper editors, and traditional leaders strongly protested Aberhart's ideas, calling them strange. But they didn't seem to offer solutions for the problems faced by Alberta's workers and farmers. Aberhart's new party in 1935 elected 56 members to the Assembly, compared to 7 for all other parties. The UFA, which had been in power, lost all its seats. The economic thinker for Aberhart was Major Douglas, an English engineer.

The Social Credit Party stayed in power for 36 years until 1971. It was re-elected by popular vote nine times. Its continued success happened as its ideas moved from left to right on the political spectrum.

Social Credit in Power

Once in power, Aberhart focused on balancing the provincial budget. He cut spending and briefly introduced a sales tax and increased income tax. The poor and unemployed saw cuts to the limited relief they had received under the UFA government. The promised $25 monthly social dividend never arrived, as Aberhart decided nothing could be done until the province's financial system was changed. For about a year (1936–37), provincially-issued Prosperity Certificates circulated, providing much-needed buying power to Alberta's struggling farmers and workers. In 1936, Alberta stopped paying its bonds, which was a very unusual step for a government in the Western world. He passed a Debt Adjustment Act that canceled all interest on mortgages since 1932 and limited all mortgage interest rates to 5%, similar to laws passed by other provinces. In 1937, the government, pressured by its members, passed a radical banking law that was rejected by the federal government (banking was a federal responsibility). Efforts to control the press were also disallowed.

Aberhart's Social Credit government was strict, and he tried to control his officials. Those who disagreed with his ideas were removed from cabinet or expelled from the party. Although Aberhart was against banks and newspapers, he generally supported capitalism and did not support socialist policies like the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in Saskatchewan. In Alberta, the CCF and Social Credit were strong rivals, especially in the early 1940s.

By 1938, the Social Credit government gave up on its promised $25 payouts. Its failure to keep election promises led many people to leave the party. Aberhart's government was re-elected in the 1940 election with 43% of the vote, against a combined Liberal-Conservative group. The prosperity of World War II eased the economic fears that had fueled farmer unrest. Aberhart died in 1943. His student and close follower, Ernest C. Manning (1908–1996), became premier.

The Social Credit party, now more conservative, governed Alberta until 1968 under Manning. He was succeeded by Harry Strom, who led the Social Credit government to defeat in the 1971 general election.

Some Social Credit activists used anti-Jewish language, which greatly concerned Canada's Jewish community. In the late 1940s, Premier Manning eventually removed these individuals from the party.

By the mid-1980s, Social Credit activists were moving into the social conservative Reform Party of Canada, led by Preston Manning, Ernest Manning's son.

Second World War

Alberta contributed a lot to Canada's war effort from 1939 to 1945. At home, prisoner of war and internment camps were set up in Lethbridge, Medicine Hat, Wainwright, and Kananaskis Country. These camps held captured enemy soldiers and also Canadian internees. Many British Commonwealth Air Training Plan airfields and training centers were established in the province. Thousands of men (and later, women) volunteered for the Royal Canadian Navy, Royal Canadian Air Force, and Canadian Army. Major David Vivian Currie, serving with the South Alberta Light Horse, was awarded the Victoria Cross, as was Calgarian Ian Bazalgette, who died in air combat. Many Alberta-based militia units provided soldiers for overseas units, including The Loyal Edmonton Regiment, Calgary Regiment (Tank), and Calgary Highlanders.

In 1942, many Japanese people from British Columbia were forcibly sent to internment camps in southern Alberta. There were already Japanese communities at Raymond and Hardieville. At first, the newly arrived Japanese were limited to working in sugar beet fields and faced severe problems with housing, schools, and water. In later years, some Japanese were allowed to work in canning factories, sawmills, and other businesses. There was ongoing debate in the news about the role and freedom of the local Japanese. Farm production increased significantly. After the war, few Japanese took advantage of the plan to return to Japan. Today, Japanese people in Alberta are well integrated into society.

After the War

After the war, the Manning government passed several laws that limited unions' ability to organize workers and call strikes. The way labor laws were enforced also showed a bias against unions. Social Credit leaders believed that union activism was part of a Communist conspiracy. Their labor laws aimed to stop this conspiracy in Alberta and also to reassure potential investors, especially in the oil industry, that Alberta was a good place for making profits. These laws were easier to pass because one part of the labor movement in the province was conservative, and the other part feared being labeled as Communist.

Conservatives and Change

In 1971, Peter Lougheed's Conservatives ended the long rule of the Social Credit Party as the Progressive Conservative Party came to power. Many experts believe that the big social changes in the province due to the postwar oil boom caused this important change in government. The growth of cities, especially the urban middle classes, and increasing wealth are often named as the main reasons for Social Credit's fall. However, some historians argue that short-term factors like leadership, current issues, and campaign organization better explain the Conservative victory.

The Conservatives stayed in power under seven different premiers for 44 years of majority governments. But in 2015, the government was defeated by a group of younger, newer candidates put forward by the Alberta NDP, led by Rachel Notley.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Alberta para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Alberta para niños