History of Edinburgh facts for kids

The city of Edinburgh has a very long and interesting history. People have lived in the area for thousands of years! The story of Edinburgh as a proper town began in the early Middle Ages. This is when a strong fort was built, probably on the Castle Rock.

From the 600s to the 900s, Edinburgh was part of the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria. After that, it became a special home for Scottish kings. The town next to the fort officially started in the early 1100s. By the mid-1300s, people were already calling it the capital of Scotland. The famous New Town area was added much later, starting in the late 1700s. Edinburgh was Scotland's biggest city until Glasgow grew larger in the early 1800s. More recently, in the late 1900s, Scotland's own Parliament was set up in Edinburgh.

Contents

Early Beginnings

The very first signs of people living in the Edinburgh area are from a place called Cramond. Here, experts found proof of a Mesolithic settlement from around 8500 BC. This means people lived there about 10,500 years ago! Later on, during the Bronze Age and Iron Age, people settled on the Castle Rock, Arthur's Seat, and other hills. Their way of life was similar to the Celtic groups found in central Europe.

Before the 600s AD, a group called the Gododdin built a hillfort. They called it Din Eidyn or Etin. This fort was almost certainly somewhere in what is now Edinburgh. While we don't know the exact spot, it was probably on the high Castle Rock, Arthur's Seat, or Calton Hill. During this time, the area known as Lothian came into being, with Edinburgh as its main stronghold. Around the year 600, a Welsh story tells us that a ruler named Mynyddog Mwynfawr gathered an army near Edinburgh. They wanted to fight against Germanic settlers from the south. However, this army was defeated by the Angles at the Battle of Catraeth.

Edinburgh Under Northumbria (600s to 900s)

The Angles were a powerful group from the Kingdom of Bernicia. They had a big impact on the Edinburgh area. This happened especially after AD 638. It seems the Gododdin fort was attacked by forces loyal to King Oswald of Northumbria. Around this time, the Edinburgh region came under the control of Northumbria.

In the years that followed, the Angles spread their power further west and north. But after they lost the Battle of Nechtansmere in AD 685, Edinburgh might have become the very edge of their kingdom. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that in 710, the Angles fought against the Picts. This battle happened between the rivers Avon and Carron, west of Edinburgh.

From the mid-600s to the mid-900s, Anglian influence was strong. Edinburgh was an important border fort. During this time, people in Edinburgh spoke a type of Old English. This is how the city got its name with the Old English ending, "-burh" (meaning a fortified place).

We don't know much about Northumbrian Edinburgh. However, an English writer named Symeon of Durham mentioned a church in Edwinesburch in AD 854. This church was under the authority of the Bishop of Lindisfarne. This suggests that there was already a settled community by the mid-800s. This church might have been an early version of St Giles' Cathedral or St Cuthbert's Church. Some stories also say that Saint Cuthbert preached near the castle rock in the late 600s.

It's not clear when a fortress was first built on the Castle Rock. Some think the Northumbrians built one in the 600s. But there isn't much proof. What we do know is that by the mid-900s, there was some kind of noble home on the site.

In the late 800s, the Danelaw was set up in England after Viking raids. This cut off the northern part of Northumbria, making the kingdom weaker. During the 900s, the northernmost part, called Lothian, came under the control of the Kingdom of Scotland. In 934, the Annals of Clonmacnoise say that the English king Æthelstan attacked Scotland as far as Edinburgh. But he had to leave without a big victory. Another old record says that "oppidum Eden" (Edinburgh) "was emptied, and given to the Scots until today." This means Lothian was given to the Scottish king Indulf (who ruled from AD 954 to 962). After this, Edinburgh usually stayed under Scottish rule.

Medieval Edinburgh (1000s to 1560)

In AD 973, the English king Edgar the Peaceful officially gave Lothian to Kenneth II, King of Scots. This was a very important event for Scottish rule over the area. By the early 1000s, Scotland's control was secure. This happened when Malcolm II won the battle of Carham in 1018, ending the Northumbrian threat.

While Malcolm Canmore (ruled 1058-1093) usually lived in Dunfermline, he started spending more time in Edinburgh. He built a chapel there for his wife, Margaret. St. Margaret's Chapel inside Edinburgh Castle is thought to be Edinburgh's oldest building. However, many experts now believe it was built by Margaret's youngest son, David I, in her memory.

In the 1100s (around 1130), King David I made Edinburgh one of Scotland's first royal burghs. A burgh was a special town with royal protection. It was built on the slope below the castle. Merchants were given pieces of land called "tofts." These were along both sides of a long market street. They had to build a house on their land within a year and a day. Each toft stretched back from the street and had a private enclosed yard. A separate town, the burgh of Canongate, grew next to it, held by the Abbey of Holyrood.

Edinburgh was mostly controlled by the English from 1291 to 1314 and from 1333 to 1341. This was during the Wars of Scottish Independence. An English nobleman, Lord Basset, became Governor of Edinburgh Castle in 1291. When the English invaded Scotland in 1298, King Edward I chose not to enter Edinburgh, even though it was under English control.

After Scotland lost its main trading port, Berwick-upon-Tweed, to the English in the 1330s, most of its valuable exports went through Edinburgh and its port, Leith. These exports included animal skins, hides, and especially wool. By the mid-1300s, during the reign of David II, a French writer described Edinburgh as "the Paris of Scotland." It had about 400 homes.

Scottish king James II (1437-60) was "born, crowned, married and buried in the Abbey of Holyrood." James III (1451–88) called Edinburgh "the principal burgh of our kingdom." By the time of James V (1512–42), Edinburgh's taxes were sometimes as much as the next three biggest towns combined. It paid a fifth or a quarter of all town taxes and half or more of all customs duties.

Even after a lot of destruction during the Hertford Raid in 1544, the town slowly recovered. Its population of merchant burgesses (town citizens) and skilled workers continued to serve the royal court and nobles. These workers included shoemakers, hatmakers, weavers, smiths, leather workers, butchers, and bakers. As town taxes increased, some of these workers moved to areas outside the town walls in the 1500s and 1600s.

In 1560, Edinburgh's population reached 12,000. Another 4,000 people lived in nearby areas like Canongate and Leith. This was when Scotland's total population was about one million. A count in 1592 showed 8,003 adults. Many of them (45%) were domestic servants in the homes of lawyers, merchants, or nobles. Even with outbreaks of the plague, the population kept growing.

The Reformation Era

Edinburgh played a key role in the Protestant Reformation in the mid-1500s. This was a time of big religious change. Mary, Queen of Scots, who was Catholic, returned to Scotland from France in 1561. She faced strong disagreements. Protestant nobles and church leaders worried that her faith and her claim to the English throne might bring back Catholicism. They were very against her rule.

At first, the people welcomed Mary. But a series of sad events happened while she lived at Holyrood Palace. This led to a crisis, and she was forced to give up her throne in 1567. John Knox, a Protestant minister in Edinburgh, preached at St. Giles. He called for Mary's execution, which made people very angry at her. After her arrest, she was held briefly in the town provost's house. This is now the site of the Edinburgh City Chambers. Then she was imprisoned in Loch Leven Castle.

Mary escaped, but was defeated at the Battle of Langside. She then fled to England. The civil war that followed ended when her last supporters surrendered. This happened during the "Lang Siege" of Edinburgh Castle in 1573.

The religious split within Scottish Protestantism continued into the 1600s. This was between Presbyterians and Episcopalians. It led to the Wars of the Covenant and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Edinburgh, as the home of the Parliament of Scotland, was very important during these wars. The Presbyterians finally won in 1689. This set the form of the Church of Scotland and made Presbyterianism the main religion across most of the country.

Union of Crowns to Union of Parliaments (1600s)

In 1603, King James VI of Scotland also became King of England. This joined the two kingdoms under one ruler, known as the Union of the Crowns. But Scotland remained a separate kingdom. It kept its own Parliament of Scotland in Edinburgh. King James VI moved to London and rarely returned to Scotland.

From 1550 to 1650, Edinburgh's town council was mostly controlled by merchants. This was true even though the king's agents tried to influence it. To get a position, social status was most important, followed by wealth. A person's religion didn't matter much. Many of these men inherited their citizen status from their fathers or fathers-in-law.

Strong Presbyterian opposition to King Charles I's attempts to introduce Anglican ways of worship led to the Bishops' Wars in 1639 and 1640. These were the first conflicts in the civil war period. In 1650, Edinburgh was taken over by the forces of Oliver Cromwell. This happened after the Battle of Dunbar. The Scots had supported the return of Charles Stuart to the English throne. A year later, a Scottish army tried to invade England but was defeated by Cromwell at the Battle of Worcester.

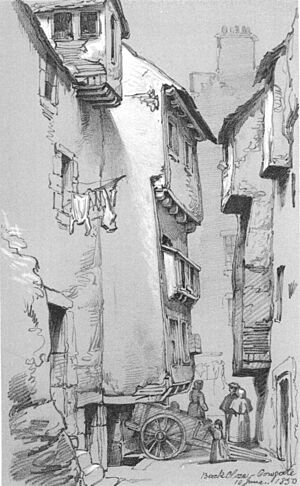

In the 1600s, Edinburgh was still contained within its "ancient royalty" of 140 acres. This area was protected by the Flodden and Telfer Walls, built mainly in the 1500s. Because there wasn't much space, houses were built very tall to fit the growing population. Buildings with 11 stories were common. Some were even taller, up to 14 or 15 stories! These tall buildings were like early versions of today's high-rise apartments. Most of these old structures were later replaced by the Victorian buildings we see in the Old Town today.

In 1706 and 1707, the Acts of Union were passed. These laws joined the kingdoms of England and Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. As a result, the Scottish Parliament joined with the English Parliament. The new Parliament of Great Britain met only in London. Many Scots were against this Union at the time, and there were riots in the city.

The 1700s

By the early 1700s, Edinburgh was becoming more wealthy. New banks like the Bank of Scotland and Royal Bank of Scotland were growing. However, Edinburgh was also one of the most crowded and unhealthy cities in Europe. Daniel Defoe, an English visitor, said that "though many cities have more people in them, yet, I believe, this may be said with truth, that in no city in the world [do] so many people live in so little room as at Edinburgh."

One striking thing about Edinburgh society in the 1700s was how close different social classes lived. Shopkeepers and important professionals often shared the same buildings.

In the tall houses in narrow alleys or facing the High Street, people lived. They reached their homes by steep, narrow staircases. In the same building, families of all types lived on different floors. Cleaners and errand boys might be in the cellars. Poor workers might be in the attics. In between, there could be a noble, a judge, a doctor, a church minister, or a wealthy widow. Higher up, shopkeepers, dance teachers, or clerks might live.

Some historians think Edinburgh's living arrangements helped create the ideas of the Scottish Enlightenment. This was a time of great thinking and learning. "Its tall tenements housed people from all parts of society. Nobles, judges, and errand boys rubbed shoulders on the same common stair. A curious person could not live in old Edinburgh without becoming a kind of sociologist."

During the Jacobite uprising of 1745, Edinburgh was briefly taken over by the Jacobite "Highland Army." After their defeat, there was a period of punishment and calming down, especially for the rebellious clans. In Edinburgh, the Town Council wanted to be like Georgian London. They wanted to make the city more prosperous and show their loyalty to the Union. So, they started improving and expanding the city.

The idea of expanding north had been discussed since the 1680s. But the real push for change came in 1752. The Convention of Royal Burghs suggested improvements to the capital for trade. They published a pamphlet, probably written by Sir Gilbert Elliot. It was strongly influenced by Lord Provost George Drummond. Elliot described the old town:

It is on a hill ridge, so it only has one good street running east to west. Even this is hard to reach from most places. The narrow lanes leading north and south are steep, narrow, and dirty. They are just unavoidable problems. The houses are squeezed together more than in any other town in Europe. They are built to an incredible height because they are limited by the small walls and narrow city boundaries.

The plans for improvement included building a new Exchange for merchants (now the City Chambers). They also planned new law courts and a library for lawyers. The city would expand north and south, and the Nor Loch would be drained. As the New Town took shape in the north, the Town Council showed its loyalty to the Union and King George III. They chose street names like Rose Street and Thistle Street. They also named streets after the royal family: George Street, Queen Street, Hanover Street, Frederick Street, and Princes Street (for George's two sons). Architects, builders, engineers, and surveyors became very important. Some of Edinburgh's best specialists even worked in London.

From the late 1760s, professionals and business people slowly left the Old Town. They preferred the nicer "one-family" homes in the New Town. These homes had separate rooms for servants. This move changed Edinburgh's social character. Robert Chambers, writing in the 1820s, described it as:

"a kind of double city—first, an ancient and picturesque hill-built one, mostly lived in by poorer people; and second, an elegant modern one, very regular, and almost entirely lived in by the more refined part of society."

According to Youngson, a historian, "Unity of social feeling was one of the most valuable things about old Edinburgh. Its disappearance was widely and rightly regretted." The Old Town became a place for the poor. An English visitor in the 1770s reported that "No people in the World undergo greater hardships, or live in a worse degree of wretchedness and poverty, than the lower classes here." From 1802, a 'Second New Town' grew north of James Craig's original New Town.

The Scottish Enlightenment

When Scotland joined with England in 1707, the Scottish Parliament ended. Many politicians and nobles moved to London. However, Scottish law remained separate from English law. This meant that the law courts and legal jobs stayed in Edinburgh. The University and medical schools also remained. Lawyers, Presbyterian church leaders, professors, doctors, and architects formed a new group of educated middle-class leaders. They became very important in the city and helped the Scottish Enlightenment to flourish.

From the late 1740s, Edinburgh became famous around the world for its ideas. This was especially true in philosophy, history, science, economics, and medicine. The Faculty of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, started in 1726, quickly attracted students from all over Britain and the American colonies. It was supported by Archibald Campbell, Scotland's most powerful political leader. This medical school became a model for the medical school at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Important thinkers of this time included David Hume, Adam Smith, James Hutton, Joseph Black, John Playfair, William Robertson, Adam Ferguson, and judges Lord Kames and Lord Monboddo. They often met for deep discussions at clubs like The Select Society and The Poker Club. The Royal Society of Edinburgh, founded in 1783, became Scotland's national academy for science and learning. Historian Bruce Lenman says their main achievement was "a new ability to understand and explain social patterns."

The Edinburgh Musical Society was formed in 1728 by wealthy music lovers. They built St Cecilia's Hall in Niddry Street in 1763 as their private concert hall. They supported professional musicians and allowed women to attend concerts. The Society had close ties to the city's Masonic lodges. It closed in 1797. An English visitor, the poet Edward Topham, described Edinburgh's strong interest in music in 1775:

- "Indeed, the level of interest shown in Music in general in this country is unbelievable. It is not only the main entertainment, but also the constant topic of conversation. You need to love music and know about it to be liked in society."

Important visitors to Edinburgh included Benjamin Franklin from Philadelphia. He came in 1759 and 1771 to meet leading scientists and thinkers. Franklin, who was hosted by his close friend David Hume, said the University had "a set of truly great men, Professors of Several Branches of Knowledge, as have ever appeared in any age or country." The novelist Smollett had a character in his book The Expedition of Humphry Clinker describe the city as a "hotbed of genius." Thomas Jefferson, writing in 1789, said that when it came to science, "no place in the world can pretend to a competition with Edinburgh."

A great example of the Scottish Enlightenment's wide impact was the new Encyclopædia Britannica. It was created in Edinburgh by Colin Macfarquhar, Andrew Bell, and others. The first edition was published in three volumes between 1768 and 1771. It had 2,659 pages and 160 pictures. It quickly became a standard reference book in the English-speaking world. The fourth edition (1810) grew to 16,000 pages in 20 volumes! The Encyclopaedia continued to be published in Edinburgh until it was sold to an American publisher in 1898. The Edinburgh Review, started in 1802, became one of the most important intellectual magazines in 19th-century Britain. It promoted Romanticism and Whig politics.

Around 1820, the city earned the nicknames "Modern Athens" and "Athens of the North." This was because its landscape was similar to Athens. Also, its new public buildings and New Town had neo-classical architecture. And, of course, it was famous as a center of learning.

The 1800s

Edinburgh's traditional industries like printing, brewing, and distilling kept growing in the 1800s. New companies in rubber, engineering, and pharmaceuticals also started. However, there wasn't as much industrial growth compared to other British cities. By 1821, Glasgow had become Scotland's largest city, overtaking Edinburgh. Glasgow had benefited from trade with North America and became a major manufacturing center.

Edinburgh's city center, between Princes Street and George Street, became mainly a business and shopping area. This meant many of the original Georgian buildings in that part of the New Town were replaced. This change was partly helped by railways reaching the city center in the 1840s.

Meanwhile, the Old Town continued to decline. It became a very crowded and unhealthy slum with high death rates. It was almost completely separated from the rest of the city. In 1865, Alexander Smith wrote about one of the poorest areas:

The Cowgate is the Irish part of the city. Edinburgh jumps over it with bridges. The people there are morally and geographically the lower classes. They stay in their own areas and rarely come up to the light of day. Many an Edinburgh man has never set foot in the street. The lives of the people in the Cowgate are as little known to respectable Edinburgh as are the habits of moles, earthworms, and miners. The people of the Cowgate rarely visit the upper streets.

After Dr. Henry Littlejohn's report on the city's health in 1865, major street improvements were made in the Old Town. This was led by Lord Provost William Chambers. The Edinburgh City Improvement Act of 1867 began changing the area into the Victorian Old Town we see today. Unlike the New Town, many of these buildings are in the mock-Jacobean style called Scots Baronial. This style is a unique Scottish contribution to the Gothic Revival and fits the "medieval" feel of the Old Town.

Clearing slums helped lower the death rate. But because there wasn't enough new, cheap housing, other poor areas became more crowded and turned into slums. This showed reformers that future projects needed to include affordable new homes.

In the world of ideas, from 1832 to 1844, Chambers's Edinburgh Journal was the most widely read magazine in Britain. It had over 80,000 copies in circulation.

The 1900s

During the First World War, Edinburgh was bombed on the night of April 2-3, 1916. Two German Zeppelin airships dropped bombs on places like Leith, the Mound, and the Grassmarket. Eleven civilians died, many were injured, and property was damaged.

Because Edinburgh had less industry, it wasn't a main target for German bombing in the early part of the Second World War. The port of Leith was hit on July 22, 1940, when a large bomb fell on the Albert Dock. But it's not clear if the target was actually the well-defended Rosyth Dockyard. Bombs were dropped on at least 11 other times between June 1940 and July 1942. These seem to have been random attacks by bombers dropping their remaining bombs while returning from other targets. So, Edinburgh avoided major loss of life and damage during the war.

The close-knit Irish Catholic community grew from many Irish immigrants in the previous century. They formed a distinct group in the city. Seán Damer remembered growing up in working-class Irish Catholic neighborhoods in the 1940s and 1950s. He described a Catholic culture surrounded by Protestant dislike and kept out of power. It was known for being inward-looking, following rules, and having rituals.

More small improvements were made to the Old Town in the early 1900s. This was thanks to the town planner Patrick Geddes. He called his work "conservative surgery." But a time of slow economic growth during and after the two world wars saw the Old Town get worse. Major slum clearance in the 1960s and 1970s started to fix things. Even so, its population dropped by more than two-thirds (to 3,000) between 1950 and 1975. Out of 292 houses in the Cowgate in 1920, only eight remained in 1980.

In the mid-1960s, the working-class area of Dumbiedykes was quickly removed. The George Square area, which was a big part of the city's original expansion in the 1700s, was lost to new University buildings. The medieval area of Potterrow, which was outside the town walls and rebuilt in the Victorian period, was also destroyed. By the late 1960s, many people felt these changes didn't respect the city's history. The historian Christopher Smout urged citizens "to save the New Town from the damage of neglect and development happening today with the council's permission."

Recent Developments

Since the 1990s, a new "financial district" has grown. It includes a new Edinburgh International Conference Centre. This area is mostly on old railway land west of the castle. It stretches into Fountainbridge, an old industrial area from the 1800s. Fountainbridge has changed a lot since the 1980s as factories and breweries closed. This ongoing development has helped Edinburgh remain the second largest financial and administrative center in the United Kingdom, after London. Financial services now take up a third of all commercial office space in the city. The creation of Edinburgh Park, a new business and technology park covering 38 acres, has also been key to the city's economic growth.

In 1998, the Scotland Act was passed. It came into force the next year. This act created a devolved Scottish Parliament and Scottish Executive (now called the Scottish Government). Both are based in Edinburgh. They are in charge of governing Scotland. However, certain matters like defense, taxes, and foreign affairs are still the responsibility of the Westminster Parliament in London.

Images for kids

-

The 12th century St Margaret's Chapel, the oldest surviving building in Edinburgh.

-

The Scottish Parliament Building with Calton Hill in the background

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |