History of Jordan facts for kids

The history of Jordan tells the story of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. It also covers the time when it was called the Emirate of Transjordan under British rule. Plus, it includes the general history of the whole Transjordan area.

People have lived in Transjordan for a very long time, even back in the Paleolithic period (Stone Age). During the Bronze Age, nomadic tribes settled here. Later, in the Iron Age, small kingdoms like the Ammonites, Moabites, and Edomites formed. Parts of the area were also controlled by the Israelites.

In ancient times, Transjordan was influenced by the Greeks and then the Romans. Under the Romans and the Byzantines, the northern part was home to the Decapolis, a group of ten cities. The famous Nabatean kingdom, with its capital at Petra, left amazing ruins that tourists and filmmakers love today.

Jordan's history continued with Muslim empires starting in the 7th century. Then, parts were controlled by Crusaders in the Middle Ages. Finally, the Mamluks ruled from the 13th century, and the Ottomans from the 16th century until World War I.

After the Arab Revolt in 1916, the British took control. In 1920, the area became part of the Arab Kingdom of Syria. When the French took over only the northern part of Syria, Transjordan was left without a clear ruler. A few months later, Abdullah, the son of Sharif Hussein, arrived in Transjordan.

In the early 1920s, Transjordan became the Emirate of Transjordan under the Hashemite Emir. This happened with a special agreement linked to the Mandate for Palestine. In 1946, the independent Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan was formed. It soon joined the United Nations and the Arab League.

In 1948, Jordan fought with the new state of Israel over lands from former Mandatory Palestine. Jordan gained control of the West Bank and added it to its territory, along with its Palestinian population. However, Jordan lost the West Bank in the 1967 War with Israel. After this, Jordan became a main base for the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in its fight against Israel.

The alliance between the PLO and Jordan ended in the bloody Black September in Jordan in 1970. This was a civil war between Jordanians and Palestinians, which caused thousands of deaths. After the war, the PLO and many of its fighters and their families had to leave Jordan. They moved to South Lebanon.

Contents

- Ancient Times: Stone Age to Iron Age

- Classical Period: Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Influence

- Middle Ages: Muslim Rule and Crusader Control

- Ottoman Rule: A Long Period of Change

- Modern Jordan: From Emirate to Kingdom

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Times: Stone Age to Iron Age

Stone Age: Early Humans in Jordan

People have lived in Jordan since the Paleolithic period, which is the Old Stone Age. We don't have buildings from this time. But archaeologists have found tools like flint and basalt hand-axes, knives, and scraping tools.

During the Neolithic period (8500–4500 BC), three big changes happened. First, people started living in small villages. They learned to grow food like grains, peas, and lentils. They also began to raise goats. The number of people grew a lot.

Second, the climate changed. The eastern desert became much hotter and drier. It became too dry for people to live there most of the year. This big climate change happened between 6500 and 5500 BC.

Third, people started making pottery from clay. This began between 5500 and 4500 BC. Pottery-making skills probably came from craftsmen in Mesopotamia.

The largest Neolithic village found in Jordan is Ein Ghazal in Amman. Its many buildings were in three different areas. Houses were rectangular with several rooms, some having plastered floors. Archaeologists found skulls covered with plaster and bitumen in the eye sockets. These were found in Jordan, Israel, the Palestinian Territories, and Syria. A statue found at Ein Ghazal is thought to be 8,000 years old. It's over a meter tall and shows a woman with huge eyes and thin arms.

Chalcolithic Period: Copper Age Discoveries

During the Chalcolithic period (4500–3200 BC), people learned to melt and use copper. They made axes, arrowheads, and hooks from it. Growing crops like barley, dates, olives, and lentils became common. Raising sheep and goats was more important than hunting. Life in the desert was probably similar to how modern Bedouins live.

Tuleilat Ghassul is a large Chalcolithic village in the Jordan Valley. Its houses were made of sun-dried mud bricks. Their roofs were made of wood, reeds, and mud. Some houses had stone foundations and large central courtyards. The walls were often painted with bright pictures of masked men, stars, and patterns. These might have been linked to their religious beliefs.

Bronze Age: Trade and Fortifications

Many villages built during the Early Bronze Age (3200–1950 BC) had simple water systems. They also had defenses to protect against attacks from nearby nomadic tribes.

At Bab al-Dhra in Wadi `Araba, archaeologists found over 20,000 tombs with many rooms. They also found mud-brick houses with human bones, pots, jewelry, and weapons. Hundreds of dolmens (large stone structures) are found in the mountains. They date back to the late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Ages.

Writing was developed in Egypt and Mesopotamia before 3000 BC. But it wasn't widely used in Jordan, Canaan, and Syria until about a thousand years later. Even so, people in Transjordan were trading with Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Between 2300 and 1950 BC, many large, fortified towns on hilltops were left empty. People moved to smaller, unprotected villages or lived a nomadic life. We don't know exactly why this happened. It was probably a mix of climate and political changes that ended the city-state system.

During the Middle Bronze Age (1950–1550 BC), more people moved across the Middle East. Trade continued to grow between Egypt, Syria, Arabia, and Canaan (including Transjordan). This helped spread new technologies and ideas. Bronze, made from copper and tin, allowed people to create stronger tools and weapons. Large communities seemed to grow in northern and central Jordan. The south was home to nomadic people called the Shasu.

New defenses appeared at places like Amman's Citadel, Irbid, and Tabaqat Fahl (Pella). Towns were surrounded by earth walls. The slopes were covered in hard plaster, making them slippery and hard to climb. Pella had huge walls and watchtowers.

The Middle Bronze Age usually ends around 1550 BC. This is when the Hyksos were forced out of Egypt. Many Middle Bronze Age towns in Canaan, including Transjordan, were destroyed around this time.

Iron Age: Kingdoms of Ammon, Moab, and Edom

During the Iron Age (1200–332 BC), Transjordan was home to the Kingdoms of Ammon, Edom, and Moab. The people in these kingdoms spoke Semitic languages. Ammon was on the Amman plateau, with its capital at Rabbath Ammon. Moab was in the highlands east of the Dead Sea, with its capital at Kir of Moab (Kerak). Edom was in the area around Wadi Araba in the south, with its capital at Bozrah. The northwestern part of Transjordan, called Gilead, was lived in by the Israelites.

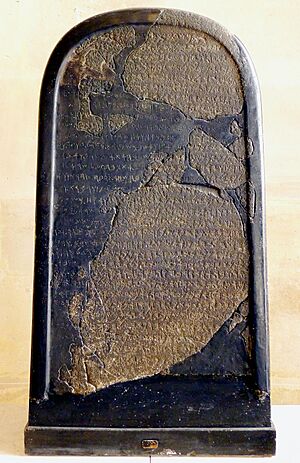

The kingdoms of Ammon, Edom, and Moab often fought with the nearby Hebrew kingdoms of Israel and Judah. These were west of the Jordan River. One important record of this is the Mesha Stele. This stone was set up by the Moabite king Mesha in 840 BC. It praises him for his building projects and his victory against the Israelites. The stele was found in Dhiban in 1868. It helps us understand stories from the Bible.

Around 720 BC, Israel and the Kingdom of Aram-Damascus were conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Ammon, Edom, and Moab benefited from trade between Syria and Arabia. In 701 BC, they gave in to the Assyrians to avoid punishment. The Babylonians took over the Assyrian empire after it fell apart in 627 BC. Even though these kingdoms helped the Babylonians against Judah in 597 BC, they rebelled against Babylon ten years later. They became vassals (states controlled by a stronger power). They stayed that way under the Persian and Hellenic Empires.

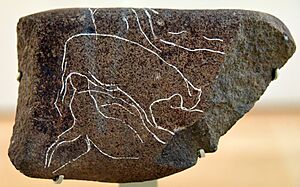

-

Iron Age walls in Tulul adh-Dhahab. Some think this was the Israelite city of Mahanaim from the Hebrew Bible.

Classical Period: Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Influence

Alexander the Great's conquests in 332 BC brought Hellenistic (Greek) culture to the Middle East. After Alexander died, his empire split. Much of Transjordan was fought over by the Ptolemies (based in Egypt) and the Seleucids (based in Syria). By the late Hellenistic period, the area had a mix of Jews, Greeks, Nabataeans, other Arabs, and descendants of Ammonites. One building from this time is Qasr al-Abd, a palace built by the Jewish Tobiad family near Iraq al-Amir.

The Nabataeans, nomadic Arabs from south of Edom, created their own kingdom in southern Jordan in 169 BC. They took advantage of the fighting between the two Greek powers. The Jewish Hasmonean Kingdom also grew, taking control of the area east of the Jordan River valley.

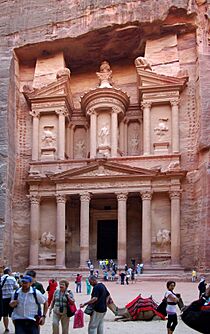

The Nabataean Kingdom slowly grew to control many trade routes in the region. It stretched south along the Red Sea coast into the Hejaz desert. It even reached as far north as Damascus for a short time. The Nabataeans became very rich from controlling trade, which made their neighbors jealous. They also controlled the Dead Sea trade. Petra, their capital, became very successful in the 1st century AD. This was thanks to its advanced water systems and farming. The Nabataeans were also skilled stone carvers. They built their most amazing structure, Al-Khazneh, in the 1st century AD. It is believed to be the tomb of the Arab Nabataean King Aretas IV.

Roman armies under Pompey conquered much of the Levant in 63 BC. This began four centuries of Roman rule. The eastern side of the Jordan River valley, then called Perea, was part of the Herodian Kingdom of Judea. This was a state controlled by the Roman Empire. By this time, the kingdoms of Ammon, Edom, and Moab had lost their separate identities. They became part of Roman culture.

The area also saw important events in Christianity, like the Baptism of Jesus. In 106 AD, Emperor Trajan took over the Nabataean Kingdom without a fight. He rebuilt the King's Highway, which became known as the Via Traiana Nova road. The Romans gave the Greek cities of Transjordan some freedom. These included Philadelphia (Amman), Gerasa (Jerash), Gedara (Umm Quays), Pella (Tabaqat Fahl), and Arbila (Irbid). They formed the Decapolis, a league of ten cities. Jerash is one of the best-preserved Roman cities in the East. Emperor Hadrian even visited it.

In 324 AD, the Roman Empire split. The Eastern Roman Empire, later called the Byzantine Empire, controlled the region until 636 AD. Christianity became legal in the empire in 313 AD. This happened after Emperor Constantine became Christian. The Edict of Thessalonica made Christianity the official state religion in 380 AD. Transjordan did well during the Byzantine era, and Christian churches were built everywhere. The Aqaba Church in Ayla was built then. It is thought to be the world's first church built for Christian worship. Umm ar-Rasas in southern Amman has at least 16 Byzantine churches.

Meanwhile, Petra became less important as sea trade routes grew. After an earthquake in 363 AD destroyed many buildings, Petra declined further and was eventually abandoned. The Sassanian Empire in the east became rivals of the Byzantines. Their frequent fights sometimes led to the Sassanids controlling parts of the region, including Transjordan.

-

Qasr al-Abd, a palace from the Hellenistic period in Iraq al-Amir. It was built by the Jewish Tobiad family (around 200 BCE).

-

The Nabataean Kingdom at its largest (85 BCE).

-

Judaea and Transjordan during the Roman period (around 1st century CE).

-

Machaerus, a Hasmonean fortress (around 90 BCE). The New Testament says John the Baptist was beheaded here. The Romans destroyed it in 72 CE.

-

Ruins of the Temple of Hercules in Amman. It was built by the Roman general Publius Julius Geminius Marcianus (around 162-166 CE).

Middle Ages: Muslim Rule and Crusader Control

In the early 7th century, the area of modern Jordan became part of the new Arab-Islamic Umayyad Empire. This was the first Muslim ruling family. They ruled much of the Middle East from 661 to 750 CE. At that time, Amman, now Jordan's capital, became an important town in "Jund Dimashq" (the military district of Damascus). It was the home of the provincial governor. There was also a "Jund al-Urdunn" ("Realm of Jordan") district, but it covered an area further north than modern Jordan.

After the Umayyads, the Abbasids ruled (750–1258). Jordan was not as important then because the Abbasids moved their capital from Damascus to Kufa and later to Baghdad.

After the Abbasids declined, parts of Jordan were ruled by different powers. These included the Crusaders, the Ayyubids, the Mamluks, and finally the Ottomans. The Ottomans took over most of the Arab world around 1517.

Ottoman Rule: A Long Period of Change

For four centuries (1516–1918), the Ottoman Empire ruled Transjordan. Their control was often weak. In the 16th century, villages in Jordan saw some growth. This was due to the stability and basic government the Ottomans brought. However, the Ottomans often had less control east of the Jordan River. This allowed local tribes to have more freedom.

Over time, powerful tribal families like the Al-Majali, Al-Fayez-Bani Sakher, and the Adwan became very important. They replaced older powerful groups.

Tribal Movements and Conflicts

Around the late 16th century, parts of the ancient Bani Sakher and Bani Dhafir tribes moved north. The Bani Sakher had roamed areas from south of Al Ula to the Golan Heights. This new migration was more permanent. The Bani Sakher and Bani Dhafir tribes fought, and the Bani Sakher won. The Bani Dhafir split, with one part going to Iraq and the other staying in Jordan, becoming the ancestors of the Adwan tribe.

The Bani Sakher also fought with the Wuld Ali Anazzah tribe. The Bani Sakher won, setting the stage for more conflicts later.

The Rise of Key Families

The Al-Majali family became powerful in Al-Karak. Around 1565, the Banu Tamim tribe in Al-Karak rebelled. The Ottomans asked Yusuf Al-Nimer for help. He captured Al-Karak. Later, the Al-Majali family returned and grew their power. They fought with other local groups, like the Imamiya and the Amr, to gain control. By the late 1700s, the Al-Majali family, especially under Yusef ibn Sulayman Majali, became the main power in Al-Karak.

The Adwan tribe also rose to power in the Belqa District. Two brothers, Fayez and Fauzan, arrived around 1640. Fayez married into a local tribe, and his son Adwan built strong tribal connections. Adwan's grandson, Hamdan, became famous for raiding a caravan. His sons continued to fight for control, eventually defeating the Mihdawiya tribe and taking over the Belqa region by 1750.

The Al-Fayez family, leading the Bani Sakher, became very influential. By the early 19th century, the Bani Sakher, under Awad bin Thiab Al-Fayez, became very strong. They often raided other tribes and gained control of many lands. In 1812, they defeated the Adwan and their allies, taking over the Balqa region.

By the mid-1800s, Fendi Al-Fayez led the Bani Sakher. His tribe was seen as the most powerful force east of the Jordan River. He even sent his son, Sattam, as an envoy to Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt. The Bani Sakher established control over many tribes and villages, including the powerful Majali family in Al-Karak.

In the late 1860s, Fendi began sharing duties with his son Sattam. Sattam focused on managing land and building up the area. An alliance was formed between the Bani Sakher and the Adwan through marriage. Sattam guided Henry Tristram, a traveler, around the country, showing a period of greater stability. Sattam also helped reveal the Moabite stone to the Western world.

The Ottomans saw the alliance between the Bani Sakher and Adwan as a threat. They sent forces to control the tribes, but it was difficult and costly.

In 1867, Circassians (Sunni Muslims from Circassia) were forced to move to the region due to persecution. The Ottomans resettled them in Amman. This was a big change for the local tribes. The Ottomans also moved Christians from Al-Karak to Madaba, a Bani Sakher stronghold. This angered Sheikh Sattam. To calm him, the Ottomans made him the official Emir Al Jizah, giving him important titles.

Late Ottoman rule saw more revolts, like the Shoubak revolt and the Karak revolt. These were hard for the Ottomans to put down. The population declined, and only nomadic Bedouins remained in many areas. Towns like Al-Salt, Irbid, Jerash, and Al-Karak had small populations. Bedouins often raided these towns, and people had to pay them for safety.

Modern Jordan: From Emirate to Kingdom

Emirate of Transjordan: A New Beginning (1921-1946)

After four centuries of Ottoman rule, Turkish control ended during World War I. The Hashemite Army of the Great Arab Revolt took over Jordan. They had help from local Bedouin tribes, Circassians, and Christians. The revolt was led by Sharif Hussein against the Ottoman Empire. Britain and France supported it. Sharif Hussein's sons, Faisal and Abdullah, were promised control over territories.

After World War I, the Ottoman Empire broke up. The League of Nations and the British and French powers redrew the Middle East's borders. The Sykes–Picot Agreement led to the French Mandate for Syria and the British Mandate for Palestine. The British Mandate included Transjordan, which was given to Abdullah about a year before the Mandate was finalized in 1923.

One reason for this was that Britain needed a role for Abdullah. His brother Faisal had lost control in Syria. Transjordan had been a "staging area" for Faisal's attempt to take over Syria, which the French defeated. After this, Transjordan was left without a clear ruler. A few months later, Abdullah arrived. Faisal became king of Iraq, and the British made Abdullah emir of the new Transjordanian state. Abdullah was not happy with the territory at first. He hoped it was only temporary and that he would get Syria or Palestine.

In 1925, international courts ruled that Palestine and Transjordan were new states formed from the Ottoman Empire.

The biggest threats to Emir Abdullah in Transjordan were repeated attacks by Wahhabi groups from Najd in southern parts of his land. The emir could not stop these raids alone. So, the British kept a military base with a small air force near Amman.

In 1928, Britain gave King Abdullah full self-rule. However, the British RAF still provided security for the emirate.

In 1920, the Emirate of Transjordan had 200,000 people. By 1948, as a Kingdom, it had 400,000. Almost half the population in 1922 (around 103,000) were nomadic.

Kingdom of Transjordan/Jordan: Independence and Growth

On March 22, 1946, Britain and the Emir of Transjordan signed the Treaty of London. This recognized Transjordan's full independence once both countries' parliaments approved it. The League of Nations recognized Transjordan's upcoming independence on April 18, 1946. On May 25, 1946, Transjordan became the "Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan". The ruling 'Amir' was renamed 'King' by the parliament. May 25 is still celebrated as independence day in Jordan. Legally, the British Mandate for Transjordan ended on June 17, 1946.

When King Abdullah asked to join the United Nations, the Soviet Union said no. They claimed Jordan was not "fully independent" of British control. This led to another treaty in March 1948, removing all limits on Jordan's independence. Still, Jordan did not become a full UN member until December 14, 1955.

In April 1949, after gaining control of the West Bank, the country's official name became the "Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan".

1948 War and West Bank Annexation

Transjordan was one of the Arab states against dividing Palestine and creating Israel in May 1948. It joined the war between Arab states and the new state of Israel. Thousands of Palestinians fled the fighting to the West Bank and Jordan. The Armistice Agreements of April 3, 1949, left Jordan in control of the West Bank. These agreements stated that the border lines did not affect future land settlements.

Historians like Benny Morris and Avi Shlaim say that King Abdullah and Jewish leaders had an agreement. They had negotiated to divide Palestine peacefully. They initially agreed to follow the UN resolution. The commander of the Arab Legion, John Baggot Glubb, wrote that Britain allowed the Arab Legion to occupy the land given to the Arab state. Jordan's Prime Minister said Abdullah received many requests from Palestinian leaders for protection when the British left.

After the British Mandate ended, Transjordan's army entered Palestine. Abdullah told the Security Council that they had to enter Palestine to protect unarmed Arabs from massacres.

After taking the West Bank during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Abdullah was declared King of Palestine. The next year, Jordan officially added the West Bank to its territory.

The United States recognized both Transjordan and Israel on the same day, January 31, 1949. President Truman wanted a balanced policy. He saw both as new states: one for Jewish refugees, the other for displaced Palestinian Arabs. He also knew about private agreements between Jewish leaders and King Abdullah.

On April 24, 1950, Jordan officially annexed the West Bank. It declared "complete unity between the two sides of the Jordan and their union in one state." All West Bank residents became Jordanian citizens. The December 1948 Jericho Conference, where Palestinian leaders met King Abdullah, voted for this annexation.

The Arab League and others considered Jordan's annexation illegal. However, Britain, Iraq, and Pakistan recognized it. Adding the West Bank more than doubled Jordan's population. Cities like Irbid and Zarqa saw their populations grow significantly.

King Hussein's Reign (1953-1999)

King Abdullah's oldest son, Talal of Jordan, became king in 1951. But he was declared mentally unable to rule and was removed in 1952. His son, Hussein Ibn Talal, became king on his eighteenth birthday in 1953.

The 1950s were a time of "Jordan's Experiment with Liberalism." The new constitution guaranteed freedom of speech, press, and association. Freedom of religion was already strong. Jordan had one of the freest societies in the Middle East during the 1950s and early 1960s.

Jordan ended its defense treaty with the United Kingdom, and British troops left in 1957. In February 1958, Iraq and Jordan announced the Arab Federation of Iraq and Jordan. This was after Syria and Egypt merged into the United Arab Republic. The Arab Federation ended in August 1958.

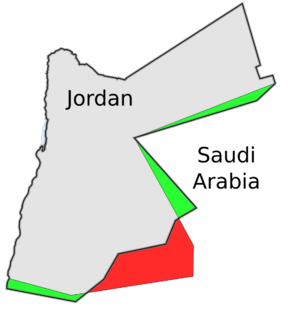

In 1965, Jordan and Saudi Arabia agreed to change their border. Jordan's coastline on the Gulf of Aqaba became longer by about eighteen kilometers. This allowed Jordan to expand its port. The agreement also shared oil revenues equally if oil was found. It also protected the rights of nomadic tribes to graze and find water.

Jordan signed a defense agreement with Egypt in May 1967. It joined Syria, Egypt, and Iraq in the Six-Day War in June 1967 against Israel. During the war, Israel took control of East Jerusalem and the West Bank. This led to another large wave of Palestinian refugees coming to Jordan. Jordan's Palestinian refugee population grew by 300,000 from the West Bank.

After the 1967 war, Palestinian militants (fedayeen) grew stronger in Jordan. Other Arab governments tried to find a peaceful solution. But by September 1970, known as Black September in Jordan, the fedayeen continued their actions in Jordan. This included destroying three international airplanes hijacked and held in the desert. This made the Jordanian government act. In the heavy fighting that followed, a Syrian tank force entered northern Jordan to support the fedayeen but was forced to leave. By September 22, Arab foreign ministers arranged a cease-fire. Fighting continued off and on until Jordanian forces defeated the fedayeen in July 1971, expelling them from the country.

An attempted military takeover was stopped in 1972. There was no fighting along the 1967 cease-fire line during the Yom Kippur War in 1973. But Jordan sent a brigade to Syria to fight Israeli units there.

In 1974, King Hussein recognized the PLO as the only true representative of the Palestinian people. However, in 1986, Hussein cut political ties with the PLO and closed its main offices. In 1988, Jordan gave up all claims to the West Bank. But it kept an administrative role until a final agreement was reached. Hussein also publicly supported the Palestinian uprising, or First Intifada, against Israeli rule.

Jordan saw some of its biggest protests in the 1980s. Students and city residents protested inflation and lack of political freedom. There were riots in several cities over price increases in 1989. That same year, the first general election since 1967 was held. Only independent candidates ran because political parties were banned in 1963. Martial law was lifted, and political reforms began quickly. Parliament was restored, and about thirty political parties, including the Islamic Action Front, were created.

Jordan did not directly join the Gulf War of 1990–91. But it supported Saddam Hussein's position in Iraq, going against most Arab countries. This led to the U.S. temporarily stopping aid to Jordan. As a result, Jordan faced severe economic and diplomatic problems. After Iraq's defeat in 1991, Jordan, along with Syria, Lebanon, and Palestinian representatives, agreed to peace talks with Israel. These talks were sponsored by the U.S. and Russia. Eventually, Jordan and Israel ended their hostilities and signed a declaration on July 25, 1994. The Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty was signed on October 26, 1994, ending 46 years of official war.

Food price riots happened in 1996 after government subsidies were removed. This was part of an economic plan overseen by the International Monetary Fund. By the late 1990s, Jordan's unemployment rate was almost 25%. Nearly half of those employed worked for the government. Several parties boycotted the 1997 parliamentary elections.

In 1998, King Hussein was treated for lymphatic cancer in the United States. He returned home to a big welcome in January 1999. But he soon had to go back for more treatment. King Hussein died in February 1999. Over 50 heads of state attended his funeral. His oldest son, Crown Prince Abdullah, became king.

King Abdullah II's Reign (1999-Present)

Economy and Development

Economic liberalization policies under King Abdullah II have helped create one of the freest economies in the Middle East.

In March 2001, King Abdullah and the presidents of Syria and Egypt opened a $300 million electricity line. This line connected the power grids of the three countries. In September 2002, Jordan and Israel agreed on a plan to pipe water from the Red Sea to the shrinking Dead Sea. This $800 million project is their biggest joint effort so far. King Abdullah and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad launched the Wahdah Dam project on the Yarmuk River in February 2004.

Foreign Relations and Regional Events

Jordan has tried to stay peaceful with all its neighbors. In September 2000, a military court sentenced six men to death. They were planning attacks against Israeli and US targets. After Israeli-Palestinian fighting started in September 2000, Amman withdrew its ambassador to Israel for four years. In 2003, Jordan's Central Bank reversed a decision to freeze accounts of Hamas leaders.

When a senior US diplomat, Laurence Foley, was killed outside his home in Amman in October 2002, many political activists were arrested. Eight militants were later found guilty and executed in 2004. King Abdullah did criticize the United States and Israel over the conflict in Lebanon in 2006.

Politics and Reforms

Jordan has slowly continued to introduce political and civil liberty. But the slow pace of reform has led to growing unhappiness. After a young man died in custody, riots broke out in the southern town of Ma'an in January 2002. These were the worst public disturbances in over three years.

The first parliamentary elections under King Abdullah II were held in June 2003. Independent candidates loyal to the king won two-thirds of the seats. A new government was appointed in October 2003 after Prime Minister Ali Abu al-Ragheb resigned. Faisal al-Fayez became prime minister. The king also appointed three female ministers. However, in April 2005, the government resigned amid reports that the king was unhappy with the slow reforms. A new government, led by Prime Minister Adnan Badran, was sworn in.

The first local elections since 1999 were held in July 2007. The main opposition party, the Islamist Action Front, pulled out. They accused the government of cheating in the votes. The parliamentary elections of November 2007 strengthened the position of tribal leaders and pro-government candidates. Support for the opposition Islamic Action Front decreased. Political moderate Nader Dahabi was appointed prime minister.

In November 2009, the King again dissolved parliament halfway through its four-year term. The next month, he appointed a new prime minister to push for economic reforms. A new election law was introduced in May 2010. But reform supporters said it did little to make the system fairer. The parliamentary elections of November 2010 were boycotted by the opposition Islamic Action Front. Riots broke out after pro-government candidates won a big victory.

Arab Spring and Arab Winter

On January 14, 2011, protests began in Jordan's capital Amman, and in Ma'an, Al Karak, Salt, Irbid, and other cities. The next month, King Abdullah appointed a new prime minister, former army general Marouf Bakhit. He was tasked with stopping the protests and carrying out political reforms. Street protests continued through the summer, though on a smaller scale. This led the King to replace Bakhit with Awn al-Khasawneh, a judge (October 2011). However, Prime Minister Awn al-Khasawneh resigned after just six months. He could not satisfy demands for reform or calm fears about empowering the Islamist opposition. King Abdullah appointed former prime minister Fayez al-Tarawneh to replace him.

In October 2012, King Abdullah called for early parliamentary elections in 2013. The Islamic Action Front continued to ask for broader political representation and a more democratic parliament. The King appointed Abdullah Ensour, a former minister and supporter of democratic reform, as prime minister.

Large protests took place in Amman in November 2012 against the removal of fuel subsidies. People publicly called for the end of the monarchy. Clashes happened between protesters and supporters of the king. The government reversed the fuel price rise after the protest. Al Jazeera said protests were expected to continue due to rising food prices.

With the fast growth of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant in northern and eastern Iraq in summer 2014, Jordan felt threatened. It sent more troops to the Iraqi and Syrian borders.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Jordania para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Jordania para niños

- Fayfa, archaeological site

- History of Asia

- History of the Middle East

- History of the Levant

- List of kings of Jordan

- Politics of Jordan

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |