History of San Diego facts for kids

The history of San Diego began when Europeans first arrived in the San Diego Bay area, which is now part of California. San Diego is often called "the birthplace of California" because it was the first place where Europeans settled in the state. Explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo was the first European to discover San Diego Bay in 1542. This was about 200 years before other Europeans settled there. Before Europeans arrived, Native American groups like the Kumeyaay people had lived in the area for as long as 12,000 years. In 1769, a fort and a mission were built. This settlement slowly grew under Spanish and then Mexican rule.

San Diego officially became part of the United States in 1848. When California became a state in 1850, San Diego was named the main city of San Diego County. For many years, it stayed a very small town. But after 1880, it grew quickly because of new buildings and many military bases. Growth was especially fast during and right after World War II. Today, San Diego's economy relies on the military, defense companies, biotechnology, tourism, international trade, and manufacturing. San Diego is now one of the largest cities in the U.S. and is the center of the bigger San Diego metropolitan area.

Contents

Early History and Spanish Rule (prehistory–1821)

First People of San Diego

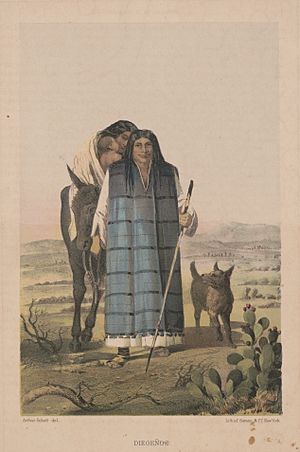

The first people to live in the San Diego area were from the La Jolla complex. They lived here between 8000 BCE and 1000 CE.

Later, groups called Yuman people moved from the east and settled in the area. They became known as the Kumeyaay. The Kumeyaay had many small villages throughout the region. One important village was Cosoy (Kosa'aay), which was where the future settlement of San Diego would begin, in what is now Old Town. Other villages included Nipaquay, Choyas, Utay, Jamo, Onap, Ystagua, and Melijo.

The Kumeyaay in San Diego spoke two different types of the Kumeyaay language. North of the San Diego River, they spoke the Ipai dialect. South of the San Diego River, they spoke the Tiipai dialect.

Spanish Explorers and Settlers

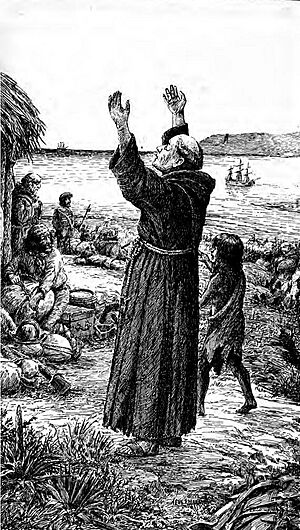

The first European to visit the San Diego region was Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542. His landing is re-enacted every year at the Cabrillo Festival. However, his visit did not lead to any settlements at that time.

The bay and the area of San Diego got their current name 60 years later. This happened in 1602 when Sebastián Vizcaíno was mapping the coast for Spain. Vizcaíno was a merchant who hoped to start successful colonies. He held the first Catholic church service in California on the feast day of San Diego de Alcala, who was also the patron saint of his ship. He then renamed the bay. Vizcaíno left after 10 days, excited about the safe harbor, friendly native people, and the area's potential for a colony. But the Spanish government was not convinced, and it would be another 167 years before they began to colonize the area.

In 1769, Gaspar de Portolà and his group founded the Presidio of San Diego (a military fort) above the village of Cosoy. On July 16, Franciscan friars Junípero Serra, Juan Viscaino, and Fernando Parron set up a cross and blessed it. This established the first mission in upper Las Californias, called Mission San Diego de Alcala. More settlers started arriving in 1774.

The next year, the Kumeyaay people rebelled against the Spanish. A priest and two others were killed, and the mission was burned. Father Serra organized the rebuilding, and a fire-proof adobe and tile-roofed building was finished in 1780. By 1797, the mission had become the largest in California. It had more than 1,400 Native Americans who lived at and were connected to the mission. An earthquake in 1803 destroyed the tile-roofed adobe building, but a third church was built in its place in 1813.

In 1804, the Province of Las Californias was divided into Alta California and Baja California. San Diego was then governed by Alta California from the capital city of Monterey.

Mexican Rule (1821–1848)

San Diego Becomes a Town

In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain in the Mexican War of Independence. This created the Province of Alta California. The San Diego Mission was closed down in 1834, and its land was sold. About 432 residents asked the governor to form a pueblo, which is a town with its own government. Juan María Osuna was elected the first alcalde (town leader). Outside of town, Mexican land grants created more California ranchos, which helped the local economy a little.

The original town of San Diego, called Pueblo de San Diego, was located at the bottom of Presidio Hill. This area is now Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. The location wasn't perfect because it was several miles from the water. Goods coming in and out (mostly animal fat and hides) had to be carried along the La Playa Trail to the ships in Point Loma. This setup only worked for a very small town. In 1830, the population was about 600 people. By 1834, the military fort was in bad shape, and the town had about 40 simple huts and a few larger, nicer homes.

San Diego's Challenges

In 1836, the Alta California and Baja California territories joined together. In 1838, San Diego lost its town status because its population had shrunk to only 100 to 150 residents. It became a smaller part of the Pueblo de Los Ángeles. This was due to growing problems between the Mexican government and the Kumeyaay people, which made the town unsafe.

Between 1836 and 1842, many ranchos were abandoned as the Kumeyaay attacked the countryside. San Diego itself was attacked around 1836–1837. A large group of Kumeyaay attacked the town, but they were surprised when an armed merchant ship, the Alert, fired on them from the bay, forcing them to leave. In 1839, a British Navy ship visited San Diego Bay, and its captain noted that it seemed San Diego might soon be taken by the "Indians" or another country.

In June 1842, the Kumeyaay launched a major raid on San Diego to try and force out the Mexican settlers. The town was able to defend itself, but the Kumeyaay gained control of much of the land around the settlement. The town became dependent on sea access to stay connected to the rest of Mexico. The Mexican settlers became refugees on Point Loma, waiting for ships to evacuate from San Diego.

Mexican–American War (1846-1848)

San Diego Changes Hands

During the Mexican–American War, the city of San Diego was captured and recaptured several times in 1846. First, American forces, including the USS Cyane ship and the California Battalion, took the city in late July. They raised the American flag. Many local Mexicans were divided; some welcomed the Americans because they disagreed with the Mexican government in Alta California.

Things changed after a revolt in Los Angeles in September 1846. In early October, Mexican forces came to San Diego to take it back. The small American group, fearing they would be defeated, left the town. The Americans and their allies boarded a whaling ship, while some local residents chose to stay neutral. The Mexican forces took control of the city without a fight.

On October 24, 1846, American forces returned to recapture San Diego. An American soldier disabled the Mexican cannons on Presidio Hill. American volunteers then retook the city after a short fight. The Mexican flag was lowered, but a local woman, María Antonia Machado, famously prevented it from being disrespected. American forces faced a siege starting October 26, when Mexican forces arrived with 100 men. The Americans, with more troops from Commodore Stockton, were surrounded in the town. There were frequent small battles. The Mexican forces tried to starve the Americans by controlling local resources and blocking supply routes.

The situation in San Diego was difficult. The surrounded Americans built defenses and dealt with sniper fire every night. Despite trying to get food, the Americans were mostly trapped. The siege continued until early December. News of General Stephen Kearney’s approaching troops led to a plan to help the town. By the end of 1846, American control was secured when more troops arrived from the USS Congress.

Battle of San Pasqual

The Americans fought the Mexican and Californio armies in the Battle of San Pasqual in December. The Americans were defeated, which was their only loss in the war. After other events near San Gabriel in early January 1847, peace returned to California.

An American Town (1848–1900)

Alta California became part of the United States in 1848 after the U.S. won the Mexican–American War and signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The border between Mexico and the U.S. was set just south of San Diego. The local "Californios" became American citizens with full voting rights. California became a state in 1850. San Diego, still a small village, was officially made a city on March 27 and became the main city of the new San Diego County. The U.S. Census reported the town's population as 650 in 1850 and 731 in 1860.

San Diego quickly got into financial trouble by spending too much money on a poorly designed jail. In 1852, the state canceled the city's charter, basically saying the city was bankrupt. A state-controlled board of three people was put in charge of managing San Diego. These trustees stayed in control until 1887, when a new city government with a mayor and council was put in place.

San Diego's Challenges and Growth

San Diego was still not completely safe after the Mexican–American War. The Kumeyaay still controlled the inland areas near the town. In 1851, San Diego County tried to tax Native American tribes and threatened to take their land if they didn't pay. This led to a revolt by the Cupeño and Kumeyaay people. The revolt was led by Cupeño leader Antonio Garra, who attacked Warner's Ranch. This started the western part of the Yuma War, aiming to secure Native American control of the Laguna Mountains and Imperial Valley. This attack worried San Diego residents, who had been preparing for another attack by the Kumeyaay. Although the conflict ended in America's favor, San Diego remained important for military reasons as the U.S. wanted to secure its position in the Pacific.

New Town San Diego

In 1850, when California joined the U.S., William Heath Davis, a pioneer, imagined a busy city on the bay. He spent $60,000 to develop a 160-acre area, which included streets, a park, a warehouse, a dock, and ten houses shipped from Maine. It was finished by August 1851, but it wasn't used much. In 1853, a ship crashed into the dock, and the damage was never fixed. The dock was poorly built and not worth repairing. Davis tried to sell it without success. Finally, in 1862, the Army destroyed it and used the wood for firewood.

The failure of the dock showed that times were tough. Houses were taken apart and sent to other, more promising settlements. By 1860, many businesses that had started in the early 1850s had closed. The few businesses that survived struggled with water shortages, high shipping costs, and a shrinking population. Davis kept trying, buying and selling land in the business district and building hotels and stores. However, in 1851, a fire destroyed his San Francisco warehouse, costing him a lot of money, and he soon ran out of funds. Leadership in promoting the city then passed to Alonzo Horton.

In 1851, San Diego's first newspaper, the San Diego Herald, was published by John Judson Ames. He continued to publish the Herald until April 1860.

Horton's Vision for San Diego

The town looked run-down in 1867 when Horton arrived, but he saw great opportunity. He said, "I have been nearly all over the world and it seemed to me to be the best spot for building a city I ever saw." He believed the town needed to be closer to the water to improve trade. Within a month of arriving, he bought over 900 acres of what is now downtown for only $265. He started promoting San Diego, attracting business owners and residents. He built a dock and encouraged development there. This area was called New Town or the Horton Addition.

Even though people in the original settlement (known as "Old Town") were against it, businesses and residents moved to New Town. San Diego then had its first of many real estate booms. In 1871, government records were moved to a new county courthouse in New Town. By the 1880s, New Town (or downtown) had completely replaced Old Town as the center of the growing city. Horton also suggested setting aside city land for a new central park, which eventually became Balboa Park.

In 1878, people thought San Diego might become a rival to San Francisco's trading ports. To prevent this, the manager of Central Pacific Railroad, Charles Crocker, decided not to build a railroad extension to San Diego. He feared it would take too much trade from San Francisco. In 1885, a transcontinental railroad route did come to San Diego, and the population grew rapidly, reaching 16,159 by 1890. In 1906, John D. Spreckels built the San Diego and Arizona Railway. This gave San Diego a direct rail link to the east by connecting with the Southern Pacific Railroad lines.

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 500 | — | |

| 1860 | 731 | 46.2% | |

| 1870 | 2,300 | 214.6% | |

| 1880 | 2,637 | 14.7% | |

| 1890 | 16,159 | 512.8% | |

| 1900 | 17,700 | 9.5% | |

| 1910 | 39,578 | 123.6% | |

| 1920 | 74,361 | 87.9% | |

| 1930 | 147,995 | 99.0% | |

| 1940 | 203,341 | 37.4% | |

| 1950 | 333,865 | 64.2% | |

| 1960 | 573,224 | 71.7% | |

| 1970 | 696,769 | 21.6% | |

| 1980 | 875,538 | 25.7% | |

| 1990 | 1,110,549 | 26.8% | |

| 2000 | 1,223,400 | 10.2% | |

| 2010 | 1,307,402 | 6.9% | |

San Diego Becomes a Regional City (1900–1941)

The city grew in bursts, especially in the 1880s and again from 1900 to 1930, when its population reached 148,000.

The Gibraltar of the Pacific

Between 1890 and 1914, the U.S. became very interested in naval affairs in the Pacific Ocean. This was seen in the Spanish–American War of 1898, the U.S. gaining Guam, the Philippines, and Hawaii, and the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914. San Diego was in a very important location and wanted to become "the Gibraltar of the Pacific" (a strong military base).

Local leaders worked hard to convince the Navy and the federal government to make San Diego a major location for naval, marine, and air bases. During World War I, the U.S. greatly expanded its Navy, and San Diego was eager to help. By the early 1920s, the Navy had built seven bases in San Diego. The city's focus on supporting the military helped it grow for many decades.

Military Bases

The southern part of the Point Loma peninsula was set aside for military use as early as 1852. Over the next decades, the Army built coastal artillery batteries there and named the area Fort Rosecrans. After World War II, this area was used for many Navy commands, including a submarine base. These were eventually combined into Naval Base Point Loma. Other parts of Fort Rosecrans became Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery and Cabrillo National Monument.

A significant U.S. Navy presence began in 1901 with a Navy Coaling Station in Point Loma. It grew much larger in the 1920s. Camp Kearny was established in 1917, closed in 1920, and later reopened. Since 1996, it has been the site of Marine Corps Air Station Miramar. Naval Base San Diego was established in 1922, as was the San Diego Naval Hospital. The Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego was started in 1921, and the San Diego Naval Training Center in 1923. The Naval Training Center closed in 1997.

In 1942, the Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton was set up 45 miles north of the city on a very large area of land. It remains one of the main Marine Corps training facilities. In the early 1990s, about 20% of the San Diego region's economy depended on defense spending.

Progressive Reforms

San Diego strongly supported the Progressive Movement in California in the early 20th century. This movement aimed to remove corruption and corporate control from the state. Reformers organized and fought back, starting with the 1905 city election. They formed groups like the Roosevelt Republican Club. Leaders like Edgar Luce and George Marston helped lead these efforts.

In 1912, city rules about public speaking led to the San Diego free speech fight. This was a conflict between a labor group called the Industrial Workers of the World and law enforcement.

Marston ran for mayor in 1913 and 1917 but lost both times. The 1917 election was a famous debate between growth and beautification. Marston wanted better city planning with more open spaces. His opponent, Louis J. Wilde, wanted more business development. Wilde called Marston "Geranium George," suggesting Marston was against business. Wilde's campaign slogan was "More Smokestacks," and he even drove a truck with a large smokestack through the city streets. The phrase "smokestacks vs. geraniums" is still used in San Diego to describe debates between environmentalists and those who want more development.

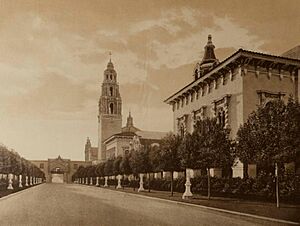

World's Fairs

San Diego hosted two World's fairs: the Panama-California Exposition in 1915–1916, and the California Pacific International Exposition in 1935–1936. These fairs left a lasting impact, creating Balboa Park and the San Diego Zoo. They also made Mission Revival Style and Spanish Colonial Revival Style architecture popular in San Diego and Southern California. The architecture for the 1915 Fair was inspired by Mexican architecture.

Tuna Industry

From the 1910s to the 1970s, San Diego was the center of the American tuna fishing fleet and tuna canning industry. It was known as the "tuna capital of the world." San Diego's first large tuna cannery opened in 1911. Other companies like Van Camp Seafood, Bumble Bee, and StarKist followed. A large fishing fleet supported these canneries, with many immigrant fishermen. Portuguese and Japanese fishermen were a big part of the industry.

By 1920, there were about 700 boats in Southern California involved in the tuna industry, and ten canneries in San Diego. By the mid-1930s, tuna was a cheap and easy food for families during the Great Depression. By 1939, the fleet's tuna catch was over 100 million pounds. During World War II, boats owned by Japanese Americans were taken by the U.S. Navy.

During World War II, when fishing was not possible, 53 tuna boats and about 600 crew members served the U.S. Navy. They were called the "yippie fleet" and delivered food, fuel, and supplies to military bases across the Pacific. Many of these vessels were lost, and crew members were killed.

In the 1950s, tuna fishing and canning was San Diego's third-largest industry, after the Navy and aviation. In 1951, there were over 800 fishing boats and almost 3,000 fishermen based in San Diego. The San Diego tuna fleet reached its peak with 160 vessels.

The industry faced problems due to rising costs and competition from other countries. In 1980, Mexico seized American tuna ships, which led to a trade ban that greatly affected the tuna fleet. Many ships moved to Mexico or were sold to other countries. The last cannery in San Diego closed in 1984, causing thousands of job losses.

The legacy of the tuna fleet is still seen in Little Italy, where many Italian fishermen settled. It's also seen in the Point Loma neighborhood of Roseville, sometimes called "Tunaville," where many Portuguese fishermen lived. There are memorials to the tuna industry in San Diego, including a sculpture in Barrio Logan and a "Tunaman's Memorial" statue on Shelter Island. The Bumble Bee Foods company is still based in San Diego.

Giving Back to the Community

Generosity played an important role in San Diego's growth. For example, wealthy heiress Ellen Browning Scripps helped fund many public facilities in La Jolla. She was also a key supporter of the new San Diego Zoo. With her brother E. W. Scripps, she established the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Another important person who gave back was George Marston, a businessman. He wanted Balboa Park to become a grand city park. He hired an architect twice to create a master plan for the park. In 1907, he bought Presidio Hill, the site of the original Presidio of San Diego, which was in ruins. Recognizing its importance as the first European settlement in California, he developed it into a park with his own money and built the Serra Museum. In 1929, he donated the park to the city.

The Great Depression in San Diego

San Diego handled the Great Depression better than most parts of the country. The population of San Diego County grew by 38% from 1930 to 1940. The city itself grew from 148,000 to 203,000 people. There was enough money to build a new golf course and tennis courts, improve the water system, and open a new campus for San Diego State College (now San Diego State University).

Government programs helped expand the Navy, bringing more money into the city. In 1935, the entire Pacific Fleet gathered in San Diego, showing America's interest in the Pacific. The growth of naval and army aviation led Consolidated Aircraft Corporation to move all its employees to San Diego. They opened a large factory, Convair, which built Navy flying boats. Ryan Aeronautical Company, which built the Spirit of St. Louis for Charles Lindbergh's famous 1927 flight, also grew. The 7.2 million visitors to the California-Pacific International Exposition in 1935–36 were impressed with the city's success.

War and Modern San Diego (1941–present)

Since World War I, the military has been very important to San Diego's economy. World War II brought prosperity and showed millions of soldiers, sailors, and airmen on their way to the Pacific the opportunities in California. Aircraft factories grew from small shops to huge factories. The city's population jumped from 200,000 to 340,000. The Navy and Marines opened training facilities, and aircraft factories rapidly hired more workers.

With many sailors off duty every weekend, the downtown entertainment areas became very busy. Workers came from all over the country, causing a severe housing shortage. Public transportation struggled to keep up, and cars had limited gas. Many wives who moved to San Diego while their husbands were training stayed in the city and took high-paying jobs in defense industries. The huge increase in the need for fresh water led the Navy to build the San Diego Aqueduct in 1944 to bring water from the Colorado River. By 1990, San Diego was the sixth largest city in the United States.

Changes in Industry

After World War I and through World War II, San Diego County had many parachute manufacturers. During World War II, one of these, Pacific Parachute Company, was owned by two African Americans. They hired a diverse group of workers and received an award in 1943. After the war, with less demand, these companies closed in San Diego. The building still stands today.

Convair was San Diego's largest employer in the mid-1950s, with 32,000 workers. In 1954, it was bought and became part of General Dynamics. Convair had been very successful with its B-36 bomber. General Dynamics then focused Convair on commercial aviation, and its Convair 240 passenger plane was very successful. However, Convair's attempt to build a medium-range jet passenger plane, the Convair 880, faced delays. After big losses, General Dynamics moved all airplane production to Texas, leaving the San Diego factory with smaller space and missile projects. Convair's employment in San Diego dropped significantly.

As the Cold War ended, the military and defense spending decreased. San Diego has since become a center for the growing biotechnology industry and is home to the telecommunications company Qualcomm. Starting in the 1990s, the city and county developed a well-known craft beer industry. The area is sometimes called "America's Craft Beer capital." By the end of 2021, there were over 150 small breweries in the county.

Tourism Growth

After the Panama-California Exposition in Balboa Park, John D. Spreckels opened the Belmont Park amusement park in 1925. San Diego's tourism began to grow beyond just beaches and Balboa Park, developing animal theme parks. The first aquatic theme park, SeaWorld, opened in San Diego as SeaWorld San Diego in 1964. The San Diego Zoo opened the San Diego Zoo Safari Park in 1972.

Historical buildings that show the city's Spanish and Mexican heritage, like Old Town San Diego State Historic Park and Mission San Diego de Alcalá, were made historical landmarks in the 1970s. San Diego also received the decommissioned USS Midway aircraft carrier, which opened as the USS Midway Museum in 2004.

The region also welcomed Legoland California in Carlsbad in 1999, the first Legoland park outside of Europe. A water park, Aquatica San Diego, opened in Chula Vista in 1997. It was later renamed Sesame Place in 2022, based on the Sesame Street children's TV show.

Universities in San Diego

After acquiring the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1912, the University of California (UC) grew its presence in San Diego, focusing on scientific research. In 1960, UC started building a new campus there, and classes at UCSD began in 1964. UCSD strengthened its ties with San Diego by encouraging new companies to use its technology.

San Diego State University (SDSU) is the largest and oldest higher education facility in San Diego County. It was founded in 1897 as San Diego Normal School, a state school for training teachers. In 1931, it moved to a larger location. In 1935, it expanded beyond teacher education and became San Diego State College. In 1970, it became San Diego State University. SDSU has grown to have over 30,000 students.

The University of San Diego, a private Catholic school, started as the San Diego College for Women in 1952. In 1972, it merged with the San Diego College for Men and the School of Law to become the University of San Diego.

Point Loma Nazarene University, a private Protestant university, moved to San Diego's Point Loma neighborhood in 1973. It is known for its academics and beautiful coastal campus.

Downtown San Diego

In the 1930s and early 1940s, the area around Fifth and Island streets had many Asian American businesses, especially Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino American ones. These businesses, particularly the Chinese American ones, had been in downtown since the 1860s. Later, this area was named the Asian Pacific Thematic Historic District.

During World War II, the internment of Japanese Americans affected downtown San Diego. Japanese American businesses had to close when families were sent to internment camps. Local officials supported these efforts. In April 1942, Japanese Americans from San Diego were taken by train to Santa Anita Park. Their personal belongings were stored at a Buddhist temple but were lost in a fire in 1943.

Up through the 1950s, the downtown area was the center of city life, with elegant hotels and department stores. During the 1970s, this focus shifted to Mission Valley with its modern shopping centers. Downtown hotels became run-down, and the area gained a bad reputation. The transformation of the downtown areas from a zone of poverty to a major tourist attraction began in 1968. The focus was on the Gaslamp Quarter, aiming to make it a historic district and bring tourists and suburban residents downtown. Since the 1980s, the city has seen the opening of the former Horton Plaza shopping center, the revival of the Gaslamp Quarter, and the building of the San Diego Convention Center.

Neighborhood Changes

A recent boom in building condos and tall buildings, especially mixed-use ones, has led to a renewal trend in areas like Little Italy. The opening of Petco Park in the once struggling East Village also shows the continued development of downtown. The downtown population is expected to grow significantly by 2030.

Another successful renewal is the Hillcrest neighborhood. It is known for its historic buildings, acceptance, diversity, and local businesses. Hillcrest has a high population density and a large and active community of people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT).

This renewal also spread to surrounding neighborhoods in the 1990s, especially older urban areas north of Balboa Park like North Park and City Heights.

City Growth and Expansion

Before World War II, San Diego added East San Diego to its city limits in 1923. After the war, development spread into areas like University City, Clairemont Mesa, Linda Vista, and Mira Mesa. The city of San Diego began rapidly expanding its boundaries.

In 1957, San Diego added San Ysidro and parts of Otay Mesa. The rest of Otay Mesa was added in 1985.

In the north, San Diego made many large additions to the city. In 1962, Rancho Bernardo was added, with plans to add more land further north. By the end of 1964, San Diego had added most of what makes up its northern city limits. This included neighborhoods like Rancho Peñasquitos, Carmel Valley, and San Pasqual Valley. San Diego's attempts to add Poway failed, and Poway became its own city in 1980.

"City of Villages" Plan

In 1979, San Diego adopted a growth plan called the "Progress Guide and General Plan." This plan divided the city into "Urbanized, Planned Urbanizing, or Future Urbanizing" areas. This policy set the pace for suburban growth north towards North County and south in Otay Mesa. This framework guided the development of areas like Torrey Highlands and Pacific Highlands Ranch. Rapid suburban growth after the 1980s replaced rural communities with large planned suburban developments, and new freeways were built to serve these areas.

In 2006, the city of San Diego set its planning policy around the "city of villages" strategy. This plan promotes building more homes and mixed-use developments within 'village centers' as San Diego runs out of land to develop.

Conventions in San Diego

In July 1971, the Republican National Committee chose San Diego to host the 1972 Republican National Convention. This was despite initial opposition from the city's mayor and the fact that the city didn't initially bid for it. Many believed San Diego was chosen because President Richard Nixon preferred it. The city and the party were preparing for the convention when, in March 1972, a large donation to the event became a national scandal. There were also problems with the planned venue and concerns about enough hotel space. In May 1972, the Republican National Committee voted to move the convention to Miami, Florida. In response, Mayor Pete Wilson declared the week of the convention "America's Finest City Week," which led to the city's unofficial slogan.

The 1996 Republican National Convention was held in San Diego in August 1996, at the San Diego Convention Center.

The largest annual convention in San Diego is San Diego Comic-Con. It started as San Diego's Golden State Comic-Minicon in 1970. According to Forbes, it is the "largest convention of its kind in the world."

Diverse Communities in San Diego

Hispanic and Latino Communities

In 1830, San Diego had 520 residents. Land was owned by the government, with only seven ranchos given to retired soldiers. In 1835, Mission San Diego was closed, and more ranchos were approved. However, due to increasing attacks by Native Americans, many ranchos were left empty. Thirty-one Californios joined the American forces to retake Los Angeles. Californios automatically became United States citizens when the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo was signed. After 1848, Californios were the majority and owned most of the property. They gained cultural and social recognition but did not control the political system. By 1860, most ranch owners had left the area or were struggling financially.

During World War II, Hispanic people made big advancements in jobs in San Diego and nearby farm areas. They gained new skills and experiences from the military. They filled many new jobs and got some higher-paying jobs in military bases and aircraft factories. They were also welcomed by labor unions.

Since the 1950s, advertisers have recognized the importance of Spanish language TV, investing in Univisión and Telemundo. The younger generations of Hispanic people in San Diego often speak less Spanish, especially outside of their families.

African American Communities

The African American population was small before the big naval expansion of World War II. Starting in 1953, the Urban League helped bring together Black and white professionals and encouraged white business owners to hire Black people. Unlike other Urban League chapters, it also worked with San Diego's Mexican American community. According to the 2010 United States Census, African Americans make up 6.6% of San Diego's total population.

For over 100 years, San Diego's second oldest neighborhood, Logan Heights, was home to African Americans. This area, along with downtown and Sherman Heights, was one of the few places where Black people were allowed to buy and live in homes. After the 1960s and the Civil Rights Act, Black people started moving out of Logan Heights into areas like Emerald Hills and Encanto. Logan Heights still has many Black churches, some over 100 years old. Many Black San Diegans return to Logan Heights on Sundays to attend the churches they grew up in.

The founders of the Black community are buried in the Logan Heights/Mountain View area. Streets in Logan Heights are named after some of these founders. For more than 70 years, Logan Heights was 90% Black. But starting in the 1980s, its population shifted to mostly Hispanic. The Black population in San Diego has been shrinking, with many moving to Southern cities in a "reverse great migration."

The history of the African American community in San Diego from the 1940s to the 1980s is shown in the Baynard Collection. This exhibit features photographs by Norman Baynard, who ran a photography studio in Logan Heights for 46 years.

East African Communities

Somalis began arriving in San Diego in the 1980s, fleeing wars in the Horn of Africa. San Diego became a destination because Somali military personnel were already stationed with U.S. troops at Camp Pendleton. They helped with logistics and language for local refugee resettlement. The refugee community grew around City Heights, alongside other war refugee groups. An estimated 10,000 Somalis lived in San Diego in the 2010s. Refugees from Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea also settled in San Diego, making the city the largest East African community in California. It is sometimes called "Little Mogadishu."

Asian/Pacific Islander Communities

Chinese Community

Immigrants from China began arriving in the 1860s and settled in two fishing villages by the water. Chinese people faced harsh discrimination in California and were often forced into Chinatowns. In San Diego, there was more freedom, and the Chinese fishermen were not attacked. They were pioneers in the fishing industry in the 1860s, specializing in abalone for export. By the 1890s, many fishermen had left.

Chinese people continued to settle in San Diego and found work in fishing, railroad construction, and other industries. They were forced into a separate Chinatown but faced less violence than Chinese people elsewhere in the West.

They formed community groups and business guilds. In the 1870s and 1880s, two Chinese Christian missions were organized to help Chinese people with housing, jobs, and English lessons. The Chinese population grew significantly, especially after the 1965 Immigration Act allowed more business people and professionals to move from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China. During this time, San Diego elected its first non-white council member, Tom Hom, who was of Chinese descent.

The modern San Diego Chinese community is diverse, with people speaking different dialects and coming from various places, including Southeast Asia. The center of San Diego's Chinese community slowly moved away from what is now the Asian Pacific Thematic Historic District. It moved north with suburban growth and Chinese immigration to areas like Kearny Mesa and Carmel Valley. The main concentration of Chinese businesses is in the Convoy District, which is now a Pan-Asian cultural district.

Filipino Community

San Diego has historically been a popular place for Filipino immigrants. The first Filipinos arrived in San Diego in 1903 as students at the State Normal School. By 1908, Filipino sailors serving in the United States Navy also arrived. Because of housing rules at the time, most Filipinos in San Diego lived downtown. Many businesses that served the Filipino community were in this area, forming a hub until at least the 1960s. Before World War II, mixed-race marriages with Hispanic and Latino women, especially Mexicans, were common due to laws against other mixed-race marriages.

After World War II, most Filipino Americans in San Diego were connected to the U.S. Navy. Many Filipino American veterans moved to the suburbs of Chula Vista and National City after their military service. Filipinos concentrated in the South Bay. More wealthy Filipino Americans moved to northern suburbs like Mira Mesa (sometimes called "Manila Mesa"). A part of California State Route 54 in San Diego is officially named the "Filipino-American Highway" to honor the Filipino American Community.

Japanese Community

Before World War II, San Diego had a thriving Japanese community. There were several blocks in what is now the Gaslamp district where Japanese people owned many businesses, along with Japanese language schools and churches. The community was built by first and second-generation Japanese immigrants. The first Japanese immigrant to make San Diego home arrived in 1887 to make Japanese-style charcoal. As time passed, they settled down and started their own businesses, including "pool halls, restaurants, barber shops, and boarding houses." This area was home to over 35 Japanese-owned businesses and was known as the Japanese business district. These businesses left buildings that are still owned by Japanese-Americans today. Some churches still stand and helped rebuild Japanese-American culture after World War II. During WWII, these Japanese-owned businesses were left empty when Japanese families were sent to internment camps.

Vietnamese Community

When the first large group of Vietnamese immigrants began arriving in 1981, many settled in communities near San Diego State University, such as City Heights and Talmadge. As families became more successful, many moved to other communities in the city like Linda Vista and Clairemont, and newer suburban areas like Mira Mesa.

In 2013, the Little Saigon Cultural and Commercial District was created in City Heights on a six-block section of El Cajon Boulevard.

Middle Eastern Communities

The San Diego region had an early Middle Eastern presence before recent U.S. wars in the Middle East. Chaldeans, in particular, built a community in El Cajon in the mid-20th century.

The first large group of people from the Middle East came to San Diego during the Iraq War, seeking safety from the war. Many found refuge in El Cajon, which has become the center of the region's Middle Eastern community and businesses. This area is informally known as "Little Baghdad." A large part of this community is made up of Chaldeans, who are mostly Christian Iraqis. Afghan immigrants escaping the Afghanistan War and other Arab and Persian groups also settled here. The region also received more Syrian refugees fleeing the Syrian civil war throughout the 2010s. Members of this community have become business owners and city leaders.

Another group of people arrived in the mid-2010s after the Syrian civil war spread to Iraq. This brought more Chaldeans to East County San Diego, mostly middle-class Chaldeans from Iraq. This has made the region have the highest number of Chaldeans in the United States.

LGBT Community

As a port city, San Diego always had a gay and lesbian community, but it was mostly hidden. Starting in the 1960s, the neighborhood of Hillcrest began to attract many gay and lesbian residents. In the 1970s, gay men founded a Center for Social Services in Hillcrest, which became a social and political center for the gay community. In June 1974, they held the first Gay Pride Parade, which has been held every year since. Hillcrest is now well-known as the main area for the LGBT community.

Many LGBT politicians have successfully run for office in San Diego city and county.

In 2011, San Diego was the first city in the country where active and retired military service members marched openly in a gay pride parade. This was before the "Don't ask, don't tell" rule for U.S. military personnel was removed. They wore T-shirts with their branch of service name. The next year, in 2012, the U.S. Department of Defense allowed military personnel to wear their uniforms while participating in the San Diego Pride Parade. This was the first time U.S. military personnel were allowed to wear their uniforms in such a parade. Also in 2012, the parade started from Harvey Milk Street, the first street in the nation named after gay civil rights icon Harvey Milk. It passed a huge new rainbow flag that was raised for the first time on July 20, 2012, to start the Pride festival.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |