History of water supply and sanitation facts for kids

The history of water supply and sanitation is all about how people have worked to get clean water and manage waste since ancient times. When communities didn't have enough clean water or good ways to get rid of waste, diseases spread easily, making people sick or even causing them to die too soon.

Early human settlements usually grew where there was plenty of fresh water, like near rivers or natural springs. Over time, people invented clever systems to bring water into their homes and towns. They also found ways to get rid of wastewater, and later, to treat it so it wouldn't harm the environment.

In the past, people often just sent raw sewage into rivers or oceans, hoping it would get diluted and disappear. But as technology improved, we learned to move water over long distances and to clean both drinking water and wastewater much better.

Ancient Times

Early Water Systems

During the Stone Age, people started digging the first permanent water wells. They would fill containers and carry water by hand. Some of the oldest wells, dating back to 8500 BCE, have been found in Cyprus and the Jezreel Valley. How big a settlement could grow often depended on how much water was nearby.

In ancient villages like Skara Brae in Scotland (around 3000 BCE), houses had simple indoor systems made of tree bark and stone. These systems seemed to handle both fresh and wastewater. Some rooms even had small areas that might have been early indoor toilets.

Using Wastewater Again

People have been reusing wastewater for a very long time, even since the first civilizations. This practice helped them manage waste outside their towns. For example, ancient civilizations like those in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and the Minoan civilization used domestic wastewater to water their crops during the Bronze Age (around 3200–1100 BC). Later, the Greeks and Romans also used wastewater for irrigation and as fertilizer around their cities.

Bronze and Early Iron Ages

Water in the Americas

In ancient Peru, the Nazca people created a system of connected wells and underground water channels called puquios to get water. The Mayans were also very advanced, using a system of indoor plumbing with pressurized water.

Water in the Near East

Mesopotamia

The Mesopotamians were using clay sewer pipes around 4000 BCE. The oldest ones were found in temples and cities like Nippur and Eshnunna. These pipes helped remove wastewater and collect rainwater. The city of Uruk also had brick-built toilets around 3200 BCE. Later, the Hittites used clay pipes that could be taken apart for cleaning.

Ancient Persia

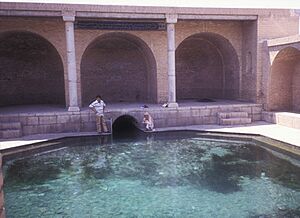

In ancient Iran, some of the first sanitation systems were built near the city of Zabol. Persians also used qanats (underground water channels) and ab anbars (water reservoirs) for water supply and even for cooling buildings.

Ancient Egypt

Around 2400 BCE, the Pyramid of Sahure and its temple complex had a network of copper drainage pipes.

Water in East Asia

Ancient China

China has some of the earliest evidence of water wells. People in Neolithic China (around 6000 to 7000 years ago) dug deep wells to get drinking water from underground. An ancient Chinese text, The Book of Changes, even describes how to maintain wells. Plumbing was also used in China during the Qin dynasty and Han Dynasty.

Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley civilization (in modern-day Pakistan and India) had very advanced public water supply and sanitation systems. Cities like Lothal (around 2350–1810 BCE) are great examples. In Lothal, important houses had private bathing areas and toilets connected to street drains. Other homes had brick bathing platforms that drained into covered sewers, which led to soak pits outside the city walls. Water came from two wells in the town.

The cities of Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Rakhigarhi also had public and private baths. Sewage went through underground drains made of carefully laid bricks. They also had smart water management systems with many reservoirs. Drains from houses connected to larger public drains. Many buildings in Mohenjo-daro had multiple stories, and water from roofs and upper bathrooms flowed through terracotta pipes or open chutes to street drains.

Tools like shadoofs were used to lift water. Ruins in places like Mohenjo-daro and Dholavira show some of the ancient world's most complex sewage systems, including drainage channels, rainwater harvesting, and street ducts. Stepwells were also commonly used in the Indian subcontinent.

Water in the Ancient Mediterranean

Ancient Greece

The ancient Greek civilization on Crete, called the Minoan civilization, built advanced underground clay pipes for sanitation and water supply. Their capital, Knossos, had a well-organized system for bringing in clean water, removing wastewater, and handling storm runoff. They even had what might have been the first flush toilets around the 16th century BC, connected to stone sewers that were cleaned by rainwater. The Greeks in Athens also used indoor plumbing for pressurized showers.

Roman Empire

In ancient Rome, the Cloaca Maxima, a huge sewer, emptied into the Tiber River. Public toilets were built over this sewer. The Romans used water wheels called norias to supply water to aqueducts and other water systems in major cities.

The Roman Empire had indoor plumbing with aqueducts and pipes that brought water to homes, public wells, and fountains. They used lead pipes, but the constant flow of water and mineral buildup helped reduce the risk of lead poisoning. Roman towns in the United Kingdom also had complex sewer networks, sometimes made from hollowed-out elm logs.

Medieval and Early Modern Ages

Water in Nepal

In Nepal, building water systems like drinking fountains and wells was seen as a good deed. A drinking water system called dhunge dhara or hiti was developed as early as 550 AD. These are carved stone fountains where water flows from underground sources. They are supported by ponds and canals that store water for the dry season and help manage monsoon rains. Even though modern piped water systems exist now, many people in Nepal still rely on these old hitis every day. In 2008, the dhunge dharas in the Kathmandu Valley produced millions of liters of water daily.

Water in the Islamic World

Islam emphasizes cleanliness. Islamic hygienical jurisprudence, from the 7th century, has detailed rules for ritual purity and bathing, which led to many bathhouses being built. Islamic toilet hygiene also requires washing with water.

In the Abbasid Caliphate (8th-13th centuries), the capital city of Baghdad had many baths and a sewer system. Cities in the medieval Islamic world had water supply systems powered by hydraulic technology, providing drinking water and large amounts of water for washing in mosques and baths. The city of Fustat even had multi-story buildings with flush toilets connected to a water supply and channels for waste.

A scholar named Al-Karaji (c. 953–1029) wrote a book about finding hidden waters. He described how water moves underground, water quality, and even an early water filtration process.

Water in Sub-Saharan Africa

In post-classical Kilwa Kisiwani, stone homes had plumbing. The Husani Kubwa Palace and other buildings for the wealthy had indoor plumbing. In the Ashanti Empire, toilets were in two-story buildings and were flushed with boiling water.

Water in Medieval Europe

Contrary to some beliefs, bathing and sanitation didn't disappear in Europe after the Roman Empire fell. Public bathhouses were common in medieval towns like Constantinople and Paris. The Church even encouraged bathing for hygiene.

However, many European cities in the Middle Ages had poor sanitation and were very crowded. This led to terrible pandemics like the Black Death, which killed millions. High rates of infant and child deaths were also common, partly due to poor sanitation.

In medieval European cities, small natural waterways used for carrying away wastewater were sometimes covered and became sewers. London's River Fleet is an example. Open drains, or gutters, ran along the center of some streets, known as "kennels." The first closed sewer in Paris was built in 1370, mainly to reduce bad smells.

In Dubrovnik, a sewage system was built in the 14th and 15th centuries, which is still used today. People used pail closets, outhouses, and cesspits to collect human waste. Most cities didn't have proper sewer systems before the Industrial era, relying on rivers or rain to wash away sewage.

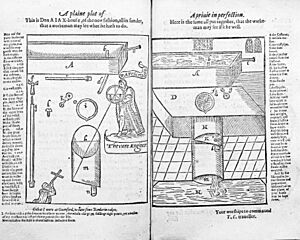

In the 16th century, Sir John Harington invented a flush toilet for Queen Elizabeth I. This toilet sent waste into cesspools. In London, the contents of outhouses were collected and used to make saltpeter, an important ingredient for gunpowder.

Water in Mesoamerica

The Classic Maya at Palenque had underground aqueducts and flush toilets. They even used household water filters made from limestone, similar to modern ceramic filters. In Spain and Spanish America, a community-run water system called an acequia combined with sand filtration provided clean drinking water.

Sewage Farms

"Sewage farms" were places where wastewater was used to water crops. This practice was common in places like Bunzlau (Germany) in 1531, Edinburgh (Scotland) in 1650, and Paris (France) in 1868. It was seen as a way to get rid of large amounts of wastewater and help agriculture. China and India also have a long history of using sewage for irrigation.

Modern Age

Modern Water Supply

Not much changed in water supply and sanitation until the 18th century. Then, as cities grew rapidly, private companies started building water supply networks, especially in London. The first screw-down water tap was patented in 1845.

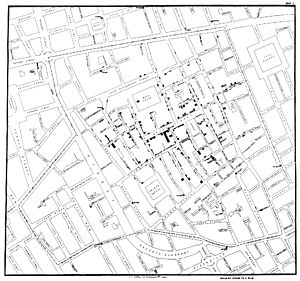

The first use of sand filters to clean water was in 1804 in Scotland. The first treated public water supply was installed in London in 1829 by James Simpson. Water treatment became very important after a doctor named John Snow showed that the water supply was spreading cholera in 1854.

Modern Sewer Systems

A big step forward was building networks of sewers to collect wastewater. Some ancient sewer systems in cities like Rome and Istanbul are still used today, but now they are connected to modern treatment plants instead of flowing directly into rivers or the sea.

Before modern sewers, cesspools were common. In ancient Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley, waste went into cesspools. In the Middle Ages, workers called 'rakers' emptied cesspools and often sold the waste as fertilizer.

Archaeological finds show that some of the earliest sewer systems were in Harappa and Mohenjo-daro (Pakistan) around 3000 BCE. These simple sewers alongside buildings show that early civilizations understood waste disposal.

As cities grew rapidly during the Industrial Revolution, overcrowding and poor sanitation led to many disease outbreaks. In the 19th century, cities started building large gravity sewer systems to control diseases like typhoid and cholera. By the 1840s, indoor plumbing became popular, which mixed human waste with water and flushed it away, reducing the need for cesspools.

Modern sewer systems were built in the mid-1800s because of the terrible sanitary conditions caused by industrial growth. A British engineer, Baldwin Latham, helped design better sewer pipes to prevent sludge buildup and flooding. After severe cholera outbreaks in London and the terrible Great Stink of 1858 (when the River Thames smelled awful from untreated waste), Joseph Bazalgette was hired to build a huge underground sewer system for London. His system piped sewage away from populated areas, usually into a natural waterway.

Sewer Systems in the UK

In the late 1800s, sewer systems in some parts of the UK were so bad that water-borne diseases were still a risk. Efforts to stop polluting the River Thames in London began as early as 1535. By the Industrial Revolution, the Thames was very polluted. Britain, being the first country to industrialize, also faced the first major problems from rapid city growth and built the first modern sewer systems.

Liverpool

In Liverpool, starting in 1847, engineer James Newlands mapped the city and designed a huge system of sewers and drains, totaling nearly 300 miles. By 1869, this program was finished. Before the sewers, life expectancy in Liverpool was only 19 years; after Newlands' work, it more than doubled.

London

Joseph Bazalgette designed London's massive underground sewer system. He built six main sewers, almost 100 miles long, some incorporating London's 'lost' rivers. These sewers were fed by 450 miles of main sewers, which in turn collected from 13,000 miles of smaller local sewers. The system used gravity to move sewage eastward, but pumping stations were built in some areas to lift the water. Bazalgette's system, built between 1859 and 1865, still forms the basis of London's sewerage today.

Paris, France

In 1802, Napoleon built the Ourcq canal to bring water to Paris. The 1832 cholera epidemic in Paris made people realize they needed a better drainage system. From 1865 to 1920, Eugène Belgrand led the development of a large water supply and wastewater management system. Aqueducts were built to bring clean spring water, allowing lower quality water to be used for flushing streets and sewers. By 1894, laws made drainage mandatory. Paris sewage was often spread on land to be naturally purified. The 19th-century brick-vaulted Paris sewers are now a tourist attraction.

Germany

The first full sewer system in a German city was built in Hamburg in the mid-19th century. In Frankfurt am Main, a modern sewer system was started in 1863. Twenty years after it was finished, the death rate from typhoid dropped significantly.

United States

The first sewer systems in the United States were built in Chicago and Brooklyn in the late 1850s. The first sewage treatment plant using chemicals was built in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1890.

Sewage Treatment

At first, sewer systems just sent sewage directly into rivers or other bodies of water without cleaning it. Later, cities tried to treat the sewage to prevent water pollution and waterborne diseases. Around 1900, these public health efforts greatly reduced water-borne diseases and helped people live longer.

Using Sewage on Farms

Early ways to treat sewage involved putting it on farmland. One of the first attempts was by James Smith in the 1840s, who piped sewage from his factory to nearby farms as fertilizer. This idea was adopted by health groups, and many "sewage farms" were tried. At first, solids were put in ditches, but later, tanks were used to collect sewage. Improvements included horizontal-flow and radial-flow tanks.

Chemical Treatment and Settling

As water pollution became a problem, cities tried to treat sewage before releasing it. In the late 1800s, some cities started adding chemicals and using sedimentation (letting solids settle) to their sewers. This process, now called "primary treatment," still left odor problems. It was later discovered that adding oxygen to sewage prevented bad smells. This led to biological treatments.

The idea for the modern septic tank came from a cesspool where water was sealed off and solid waste slowly broke down. It was invented in France in the 1860s and improved in 1895, becoming known as a 'septictank' (meaning 'bacterial'). These are still used worldwide, especially in rural areas.

Biological Treatment

It wasn't until the late 19th century that scientists learned to treat sewage by using microorganisms to break down organic parts and remove pollutants. Land treatment became less practical as cities grew.

Edward Frankland showed in the 1870s that filtering sewage through gravel could clean it. This led to the idea of biological treatment using a "contact bed" to break down waste. This method became popular in the UK and US. In 1890, the 'trickling filter' was developed, which worked even better.

Contact beds were tanks filled with materials like stones, providing a large surface area for microbes to grow and break down sewage. This method spread quickly. The Royal Commission on Sewage Disposal set an international standard for sewage discharge into rivers in 1912.

Activated Sludge Process

Most Western cities added more effective sewage treatment systems in the early 20th century. This was after scientists at the University of Manchester discovered the activated sludge process in 1912, which uses a mix of bacteria and air to clean water.

Toilets

With the Industrial Revolution, the flush toilet began to look like its modern form in the late 18th century. In cities, toilets are usually connected to a municipal sanitary sewer system. In rural areas, they often connect to a septic system. If these aren't possible, dry toilets are an option.

Water Supply (Modern)

An ambitious project to bring fresh water to London was started by Hugh Myddleton between 1609 and 1613, building the New River. This company became one of the largest private water companies. The first civic system of piped water in England was in Derby in 1692, using wooden pipes.

In the 18th century, London's growing population led to many private water supply networks. The Chelsea Waterworks Company was set up in 1723. Other waterworks were also established around London. The S-bend pipe was invented by Alexander Cummings in 1775, later becoming known as the U-bend. The first screw-down water tap was patented in 1845.

Water Treatment (Modern)

Sand Filter

Francis Bacon tried to clean sea water by passing it through a sand filter, which sparked new interest in water purification. The first documented use of sand filters to clean public water was in 1804 in Scotland. This method was improved, leading to the first treated public water supply in the world, installed by James Simpson for the Chelsea Waterworks Company in London in 1829. This system provided filtered water to everyone in the area and was widely copied.

The Metropolis Water Act 1852 set minimum water quality standards for London. It required all water to be "effectually filtered" by 1855. This led to mandatory water quality inspections and set a global example for public health actions. Automatic pressure filters were invented in England in 1899.

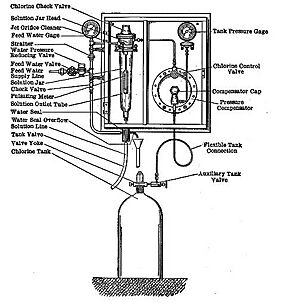

Water Chlorination

In 1879, William Soper used chlorinated lime to treat sewage from typhoid patients. In 1894, Moritz Traube suggested adding chloride of lime to water to kill germs. In 1897, Maidstone, England, was the first town to treat its entire water supply with chlorine.

Permanent water chlorination began in 1905 in Lincoln, England, after a typhoid epidemic. Dr. Alexander Cruickshank Houston used chlorine to stop the outbreak. The first continuous use of chlorine for disinfection in the United States was in 1908 in Jersey City, New Jersey. This method quickly spread worldwide.

The idea of purifying drinking water with compressed liquid chlorine gas was developed by Vincent B. Nesfield in 1903. U.S. Army Major Carl Rogers Darnall demonstrated this in 1910. Major William J. L. Lyster later used a solution of calcium hypochlorite in a linen bag to treat water, leading to the well-known Lyster Bag used by the U.S. Army for decades. This work became the basis for modern municipal water purification.

Fluoridation

Water fluoridation is the practice of adding fluoride to drinking water to help prevent tooth decay. Dr. H. Trendley Dean began studying fluoride in 1931. He found that small amounts of fluoride (up to 1.0 ppm) in drinking water didn't cause problems for most people and helped prevent cavities. In 1945, Grand Rapids, Michigan, became the first city in the world to add fluoride to its drinking water.

Current Trends

The Sustainable Development Goal 6, set in 2015, aims to ensure access to water supply and sanitation globally. In developing countries, people are often improving their water and sanitation services step-by-step, paying for it themselves. Decentralized wastewater systems, which treat water closer to where it's used, are also becoming more important for sustainable sanitation.

Understanding Health and Water

The Greek historian Thucydides (around 460 – 400 BC) was one of the first to write that diseases could spread from one person to another. The Mosaic Law in the Hebrew Bible also has early ideas about disease spread, with instructions on quarantine and washing for leprosy.

Ancient theories suggested that diseases spread through tiny "seeds" in the air. The Roman poet Lucretius (around 99 BC – 55 BC) wrote that the world contained "seeds" that could make people sick if inhaled or eaten. The Roman statesman Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC) warned about tiny creatures near swamps that could enter the body and cause serious diseases.

The Greek physician Galen (AD 129 – around 200/216) thought that some patients might have "seeds of fever" or "seeds of plague" in the air. A scholar named Ibn al-Haj al-Abdari (c. 1250–1336) warned about impurities that could contaminate water and spread through the water supply.

For a long time, people believed that drinking plain water could cause problems, so they preferred processed drinks like beer, wine, and tea. For example, on the Silk Road, people drank a lot of tea because they thought unboiled water caused blisters.

In the 19th century, during the Industrial Revolution, people in Europe started to understand waterborne diseases. Diseases like cholera were first blamed on "bad air" (the miasma theory). However, people began to see a link between water quality and diseases, leading to water purification methods like sand filtering and chlorinating drinking water.

Early microscopists like Antonie van Leeuwenhoek and Robert Hooke saw tiny particles in water, which helped lay the groundwork for understanding germs and waterborne diseases.

Britain, as a center of rapid city growth in the 19th century, faced many health problems, including cholera outbreaks. The investigations of doctor John Snow in the UK during the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak clearly showed the connection between waterborne diseases and polluted drinking water. Even though the germ theory of disease wasn't fully developed yet, Snow's observations led him to doubt the miasma theory. His 1855 essay used maps and statistics to prove that people who drank from contaminated sources, like the Broad Street pump, got cholera much more often. His data convinced the local council to disable the pump, which quickly ended the outbreak.

Edwin Chadwick played a key role in Britain's sanitation movement. Although he used the miasma theory, he helped improve sanitation. It was John Snow and William Budd who introduced the idea that cholera was caused by contaminated water.

People found that purifying and filtering water improved its quality and reduced waterborne diseases. In the German town Altona, a sand filtering system for water supply was used. A nearby town without filtering suffered an outbreak, while Altona remained unaffected, proving the link between water quality and disease. After this, Britain and Europe started filtering and chlorinating their drinking water to fight diseases like cholera.

Related Concepts

- Laundry

- Night soil

- Rainwater harvesting

- Water industry

See Also

- Ancient water conservation techniques

- Water supply and sanitation in the Indus-Saraswati Valley Civilisation

- History of stepwells in Gujarat

- Sanitation in ancient Rome

- Traditional water sources of Persian antiquity

- List of water supply and sanitation by country

- History of water filters

Images for kids

-

Skara Brae, a Neolithic village in Orkney, Scotland with home furnishings including water-flushing toilets, 3180 BC–2500 BC

-

A Chinese ceramic model of a well with a water pulley system, excavated from a tomb of the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) period

-

A large well and bathing platforms at Harappa, remains of the city's final phase of occupation from 2200 to 1900 BCE

-

The bathroom-toilet structure of the ruler's house, on Lothal's acropolis c.2350 BCE

-

Bathing platform and communal drain, Lothal's acropolis, c.2350 BCE

-

Well, and drain, Lothal's acropolis, c.2350 BCE

-

Pont du Gard, a Roman aqueduct in France.

-

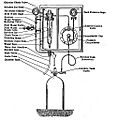

A 1939 conceptual illustration showing various ways that typhoid bacteria can contaminate a water well (center)

-

Waterworks (Wasserkunst) and fountain from 1602 in Wismar, Germany

-

Many industrialized cities had incomplete public sanitation well into the 20th century. Outhouses in Brisbane, Australia, around 1950.

-

The Great Stink of 1858 stimulated the construction of a sewer system for London. In this caricature in The Times, Michael Faraday reports to Father Thames on the state of the river.

-

The sewer system of Memphis, Tennessee in 1880

-

Chelsea Waterworks, 1752. Two Newcomen beam engines pumped Thames water from a canal to reservoirs at Green Park and Hyde Park.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |