Indigenous architecture facts for kids

Indigenous architecture is all about designing and building homes and spaces for, by, and with Indigenous people. It's a special field of study and practice in many countries like the United States, Australia, Aotearoa/New Zealand, Canada, and the Arctic area of Sápmi. This field helps Indigenous cultures express themselves through buildings and landscapes. It also includes landscape architecture, urban design, and creating public spaces.

Contents

- Australia: Building with Culture and Climate

- Canada: Homes Across Diverse Lands

- New Caledonia (Kanaky): Celebrating Kanak Culture

- New Zealand/Aotearoa: Māori Homes and Meeting Places

- Sápmi: Arctic Dwellings

- Samoa: Open Homes by the Sea

- Fiji: Simple and Practical Designs

- Palau: Important Meeting Houses

- United States: Diverse Indigenous Styles

- Philippines: The Bahay Kubo

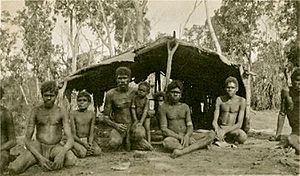

Australia: Building with Culture and Climate

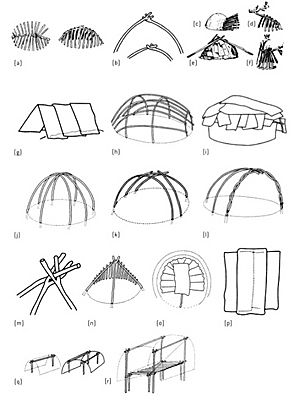

Traditional buildings made by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia were very clever. They changed their designs to fit their way of life, family size, culture, and the weather and materials available in each area.

These buildings came in many shapes. Some were dome-shaped frames made of cane, others were arc-shaped with spinifex plants. There were also tripod and triangular shelters. Some were long, egg-shaped, stone-based structures with timber frames. Others were pole and platform constructions.

Many yearly base camps, like dome houses in the rainforests of Queensland and Tasmania, or stone houses in south-eastern Australia, were built to be used for many years by the same families. Different language groups had different names for these shelters, such as humpy, gunyah, goondie, wiltja, and wurley.

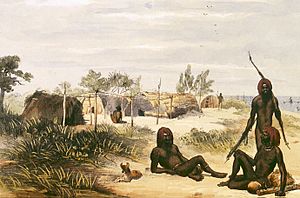

Before the 20th century, many non-Indigenous people wrongly thought Aboriginal people didn't have permanent buildings. This was because they didn't understand Aboriginal ways of life. Calling Aboriginal communities 'nomadic' helped early settlers take over their lands, claiming no one lived there permanently.

Some Indigenous groups used stone for building. For example, the Gunditjmara people in Western Victoria used basalt rocks around Lake Condah. They built houses and complex systems of stone weirs, fish, and eel traps in water channels. Their lava-stone homes had circular stone walls over a meter high, topped with a dome roof made of earth or sod.

Other parts of Australia also show advanced stone building. In 1894, about 500 people still lived in stone houses near Bessibelle. These homes had sod roofs over timber frames. In New South Wales’ Warringah area, stone shelters were egg-shaped and filled with clay to keep them dry.

Australian Indigenous Housing Design

Housing for Indigenous people in Australia has often faced big problems. There aren't enough homes, they are often poorly built, and they don't always suit Indigenous ways of life. Fast population growth, shorter building lifespans, and rising costs have made it hard for governments to provide good, healthy homes.

Two main ideas guide the design of Indigenous housing in Australia: Health and Culture.

The cultural design idea tries to include Aboriginal cultural norms in house designs. Many experts believe that housing should support Indigenous residents' social needs, daily habits, cultural values, and hopes. Not understanding these diverse cultural needs has been a reason why some Aboriginal housing projects have failed. Western-style houses can sometimes make it hard for Indigenous residents to practice their cultural norms. This can cause stress if living in a house strains relationships.

Experts have pointed out many cultural factors. These include designing homes to allow for avoidance behaviors (like not speaking to certain relatives), different household group structures, sleeping and eating habits, cultural ideas about crowding and privacy, and how people react to death. All research shows that each housing design should be unique to respect the many different Indigenous cultures across Australia.

The health approach to housing design started because housing greatly affects the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Badly built or poorly maintained homes and broken infrastructure can cause serious health problems. The 'Housing for Health' method helps measure, rate, and fix parts of a house that are important for health.

This approach uses nine 'healthy housing principles':

- The ability to wash people (especially children).

- The ability to wash clothes and bedding.

- Removing waste.

- Improving nutrition and food safety.

- Reducing the impact of crowding.

- Reducing the impact of pests, animals, and vermin.

- Controlling dust.

- Temperature control.

- Reducing trauma.

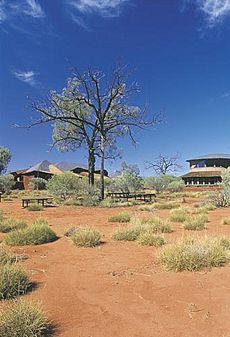

Modern Indigenous Architecture in Australia

What counts as 'Indigenous architecture' today is a topic of discussion. Many experts agree that it includes projects designed with Indigenous clients or those that show Aboriginal culture through consultation. This can also include buildings for non-Indigenous users that still reflect Aboriginal ideas.

Many projects have been designed for, by, or with Indigenous people. Using research and talking to communities has led to museums, courts, cultural centers, and schools being designed to meet the unique needs of Indigenous users.

Some important projects include:

- Brambuk Cultural Centre (Halls Gap, Victoria)

- Marika Alderton House (Yirrkala, Northern Territory)

- Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre (Uluru, Northern Territory)

- West Kimberley Regional Prison (Derby, Western Australia)

- Walumba Elders Centre (Warrmarn, Western Australia)

Today, Indigenous architecture is also shaped by Indigenous architects and designers who have studied at universities. They bring together traditional Indigenous cultural ideas and modern building styles.

Leading Architects and Researchers

Some important people in this field are:

- Sarah Lynn Rees (Palawa)

- Jefa Greenaway

- Dillon Kombumerri

- Kevin O'Brien

- Glenn Murcutt

- Gregory Burgess

Important researchers include:

- Danièle Hromek (Budawang/Yuin)

- Carroll Go-Sam (Dyirrbal gumbilbara)

- Elizabeth Grant

- Paul Memmott

Indigenous Design Methods

Indigenous designers in Australia often use a method called "Country-centred design" or "designing with Country." This approach focuses on the Indigenous understanding of Country (with a capital C), which includes land, water, sky, and all living things. This method has been used by Indigenous peoples for generations.

Canada: Homes Across Diverse Lands

The original Indigenous people of Canada had amazing building traditions thousands of years before Europeans arrived. Canada has five main cultural regions, each with its own climate, geography, and environment. These conditions, along with available materials, ways of life, and spiritual beliefs, led to unique building styles.

A key feature of traditional Canadian architecture was how well the buildings fit cultural values. The wigwam, tipi, and snow house were perfect for mobile hunting and gathering cultures. The longhouse, pit house, and plank house were different solutions for more permanent homes.

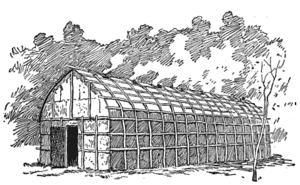

Semi-nomadic peoples in areas like Quebec and Northern Ontario, such as the Mi'kmaq, Cree, and Algonquin, often lived in wigwams. These were wood-framed structures, usually cone-shaped, covered with bark or woven mats. When they moved, they took the outer layer and left the frame, which could be reused later.

Further south, the Iroquois lived in permanent farming settlements with hundreds or thousands of people. Their main housing was the longhouse. These were large buildings, much longer than they were wide, housing many people. They were built with sapling frames covered with bark or mats.

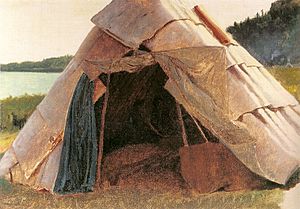

On the Prairies, people often moved daily to follow bison herds. So, their homes needed to be portable. This led to the development of the tipi. A tipi had a thin wooden frame and an outer covering of animal hides. They could be set up quickly and were light enough to carry long distances.

In the Interior of British Columbia, the common home was the semi-permanent pit house. Thousands of these, called quiggly holes, are still found today. They were bowl-shaped structures placed over a 3- or 4-foot-deep pit. The wooden bowl was covered with earth for insulation. People entered by climbing down a ladder through the roof.

Some of the best designs came from settled people on the North American west coast. Groups like the Haida used advanced carpentry skills to build large houses from red cedar planks. These were big, strong, square houses. A special design was the six beam house, named for its roof supports. The front of these houses often had a heraldic pole, sometimes brightly painted with art.

In the far north, where wood was scarce, strong shelter was vital. Unique styles developed, like the igloo, a warm, domed structure made of snow. In summer, when igloos melted, people used tents made of seal skin. The Thule used a design similar to pit houses, but they used whale bones for the frame because wood was rare.

Beyond just shelter, these buildings showed spiritual beliefs and cultural values. In all regions, homes connected people with the universe. Buildings were often seen as models of the cosmos, holding strong spiritual meaning that helped define the group's identity.

The sweat lodge is a hut, usually dome-shaped and made from natural materials. Indigenous peoples of the Americas use it for ceremonial steam baths and prayer. Different cultures have different styles, from wigwam-like huts to permanent wood and earth structures. Stones are heated, and water is poured over them to create steam. This is often done with traditional prayers and songs.

Housing Challenges in Modern Canada

As more settlers arrived in Canada, Indigenous peoples were encouraged to move to reserves. The Canadian government wanted them to build permanent houses and farm instead of hunting. Many were not used to this settled life. After World War II, Indigenous people didn't benefit much from Canada's housing and economic boom. Many stayed on remote reserves in crowded homes that often lacked basic facilities.

Since the 1960s, housing conditions on reserves haven't improved much. Overcrowding is still a big problem. Many houses need serious repairs or lack basic services. These poor housing conditions have led many Aboriginal people to leave reserves and move to cities, facing issues like homelessness and poverty.

Modern Indigenous and Métis Architecture in Canada

Today, Indigenous architects and designers are creating new buildings that blend traditional ideas with modern styles.

Some important projects include:

- First Nations Longhouse (University of British Columbia, Vancouver)

- The Canadian Museum of History (Gatineau, Quebec)

- The Spirit Garden (Prince Arthur's Landing, Thunder Bay, Ontario)

- First Nations University (Regina, Saskatchewan)

- Squamish Lil'wat Cultural Centre

Leading Architects and Researchers

Some important people in this field are:

- Douglas Cardinal

- Patrick Stewart

- Alfred Waugh

- Brian Porter

- Étienne Gaboury

Important researchers include:

- Wanda Dalla Costa

- David Fortin, the first Indigenous Director of an architecture school in Canada.

New Caledonia (Kanaky): Celebrating Kanak Culture

Kanak cultures have developed in the New Caledonia islands for over three thousand years. Today, France governs New Caledonia, but the Kanak people want independence and see their culture as a national identity. Kanaks live across all the islands of New Caledonia and its dependencies.

Kanak society is organized around clans, which are social and spatial groups. A clan might start with people related by a common ancestor. Over time, clans changed as new people joined or members left.

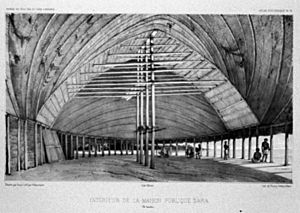

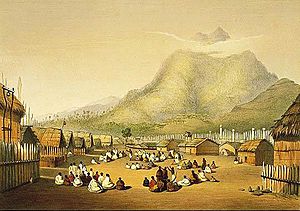

Traditionally, a village is set up with the Chief's hut (called La Grande Case) at the end of a long, wide central path used for gatherings. The Chief's younger brother lives at the other end. Other villagers live in huts along the central path, which is lined with trees for shade. For Kanak people, space is divided: areas for important men, and other residences closer to women and children.

Inside a Grande Case, a central pole (made of houp wood) holds up the roof and the rooftop spear, called the flèche faîtière. Carved posts along the walls represent ancestors. The door has two carved door posts (Katana), which were seen as "sentinels who reported strangers." There's also a carved door step. The rooftop spear has three parts: an upward spear to block bad spirits, a face representing the ancestor, and a bottom spear to keep bad spirits from rising.

The flèche faîtière is the home of ancestral spirits. It has a flat, crowned face in the center for the ancestor. A long, rounded pole with conch shells symbolizes the ancestor's voice. The base connects the clan through the chief to the central pole of the hut. Pointed wood pieces fan out to stop bad spirits from reaching the ancestor. It represents the community of ancestors and the link between the living and dead worlds.

The arrow or spear usually has a needle to insert threaded shells. One shell holds items to protect the house and country. In wars, enemies would attack this symbolic finial. After a Kanak chief dies, the flèche faîtière is removed and taken by his family. It's usually kept at burial grounds or abandoned grand houses as a sign of respect.

Building shapes varied by island, but were generally round with conical roofs. The traditional hut shows how occupants lived and organized themselves. Huts are made entirely from plants found in nearby forests, so materials differ by area. Inside, a hearth is built on the floor between the entrance and the central pole. This collective living space is covered with pandanus leaf mats and coconut leaf mattresses. The round hut represents Kanak culture and social relations within the clan.

Modern Kanak Architecture

Modern Kanak society has different levels of traditional authority, from family-based clans to eight customary areas. Clans are led by clan chiefs and form tribes, which are grouped into customary chiefdoms.

The Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre, designed by Italian architect Renzo Piano and opened in 1998, is a famous symbol of Kanak culture and modern Kanak architecture.

The Centre was built on the Tinu Peninsula, near Nouméa, the capital of New Caledonia. It celebrates the traditional Kanak culture. It was named after Jean-Marie Tjibaou, a leader who wanted a cultural center to preserve Kanak language and art.

Piano blended Kanak building traditions with modern architecture. The center has ten large, conical pavilions, shaped like traditional Kanak Grand Huts. The surrounding landscape also uses traditional Kanak design. Marie Claude Tjibaou, Jean-Marie Tjibaou's widow, said it was a "culmination of a long struggle for the recognition of our identity."

The building's design connects the landscape and structures, which is important in Kanak traditions. The plan aimed to create a unique building that would be "a symbol and... a cultural centre devoted to Kanak civilization." The design came from many discussions in 'Building Workshops' with Piano and experts on Kanak culture.

The center used Kanak village planning ideas, with the Chief's house at the end of a public path lined by other buildings. Landscaping around each building was also important. A special path with different plants leads to the center, representing the myth of the first human. The path and center blend together, showing the collaborative design process. The tall huts look unfinished, opening to the sky, to show Kanak culture as flexible and always growing.

Another important project is the Mwâ Ka, a 12-meter totem pole topped with a chief's hut. It stands in a landscaped square opposite the Musée de Nouvelle-Calédonie. Mwâ Ka means "house of mankind," a place for discussions. Its carvings show the eight customary regions of New Caledonia. The Mwâ Ka was built to remember September 24, the day France took over New Caledonia in 1853. It turned a day of sadness into a celebration of Kanak identity.

New Zealand/Aotearoa: Māori Homes and Meeting Places

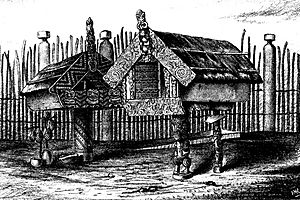

The first homes of the ancestors of Māori were based on houses from their Polynesian homelands. Māori arrived in New Zealand no later than 850 A.D. They soon changed their building methods to suit the colder climate. They kept many traditional island techniques but used new materials like raupo reed, toetoe grass, and native timbers. Early sleeping houses were rectangular, round, or oval, similar to those in Tahiti.

These early buildings were semi-permanent because people moved to find food. Houses had wooden frames covered in reeds or leaves, with mats on earth floors. To stay warm, houses were small with low doors and an inside fire. The standard home was a simple whare puni (house/hut), about 2x3 meters, with a low roof, earth floor, no window, and one low doorway. There was no chimney. Materials varied, but raupo reeds, flax, and totara bark were common for roofs.

Around the 15th century, communities grew larger and more settled. People built wharepuni – sleeping houses for several families, with a front porch. Other buildings included pātaka (storehouses), sometimes decorated with carvings, and kāuta (cooking houses).

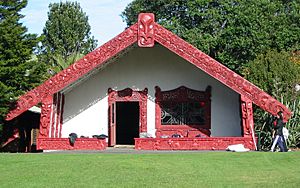

The classic period (1350-1769) saw more developed tribal societies, shown in wood carving and architecture. The most impressive building was the whare-whakairo, or carved meeting house. This building was central to Māori gatherings and showed a long tribal history. Wall carvings depicted warriors and chiefs. Painted rafter patterns showed Māori love for the land. The whare-whakairo was a colorful mix of art and architecture, honoring ancestors and nature.

Whare whakairo are often named after ancestors and are seen as embodying that person. The house is like an outstretched body and can be spoken to as a living being. A wharenui (meaning 'big house'), also called a meeting house, is a communal house usually at the center of a marae. The current style of wharenui started in the early to mid-1800s.

These houses are often carved inside and out with images of the iwi's (tribe's) ancestors. The carving style differs from tribe to tribe. Houses always have names, sometimes an ancestor's name or a figure from Māori mythology. While a meeting house is sacred, it's not a church, but religious rituals can happen there. On most marae, food is not allowed inside the meeting house.

The building often symbolizes an ancestor:

- The koruru at the front gable can be the ancestor's head.

- The maihi (diagonal bargeboards) are the arms.

- The tāhuhu (ridge beam) is the backbone.

- The heke or rafters are the ribs.

- Inside, the poutokomanawa (central column) can be the heart.

Other important parts include:

- The amo, vertical supports for the maihi.

- The poupou, wall carvings under the verandah.

- The kūwaha or front door, with the pare or door lintel.

- The paepae, the horizontal piece on the ground at the front, acting as the threshold.

Food was not cooked in the sleeping whare but outdoors or under a kauta (lean-to). Valuable items were stored in pole-mounted shelters called pataka. Large racks were used for drying fish.

The marae was the village's central place. Here, culture is celebrated, tribal duties are met, and customs are discussed. Family events like birthdays and important ceremonies, such as welcoming visitors or farewelling the dead (tangihanga), take place here.

Modern Māori Architecture

Rau Hoskins defines Māori architecture as anything involving a Māori client with a Māori focus. He says that traditionally, Māori architecture was mainly marae and churches. Now, it includes Māori immersion schools, medical centers, tourism projects, and domestic Māori villages. The purpose of the building and the client's hopes are key to how the architecture looks.

Since the 1960s, marae complexes have been built in cities. Today, these are usually groups of buildings around an open space. They host events like weddings, funerals, and church services, following traditional customs. They also serve as a base for one or more hapū (sub-tribes). The marae is still a wāhi tapu, a 'sacred place' with cultural meaning. They now include buildings like wharepaku (toilets) and whare ora (health centers). Meeting houses are still large spaces with a porch and one door and window at the front. In the 1980s, marae began to be built in prisons, schools, and universities.

Some important projects include:

- Tānenuiarangi, Wharenui at Waipapa Marae, (University of Auckland)

- Futuna Chapel (Karori, Wellington)

Leading Architects and Researchers

Some important people in this field are:

- John Scott

- Rewi Thompson (Ngāti Porou and Ngāti Raukawa)

- Elisapeta Heta (Ngāti Wai)

- Rau Hoskins

Important researchers include:

- Deidre Brown (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu)

Sápmi: Arctic Dwellings

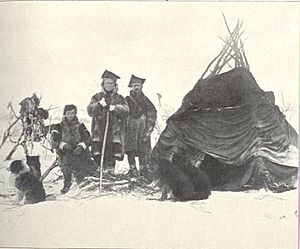

Sápmi is the traditional land of the Sámi (also Saami) people. The Sámi are the Indigenous people of northern Scandinavia and parts of the Kola Peninsula. This area includes parts of northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. The Sámi are the only Indigenous people in Scandinavia recognized and protected by international agreements. They are also the northernmost Indigenous people of Europe. Sámi ancestral lands cover about 388,350 square kilometers across the Nordic countries.

There are several Sámi traditional building types, including the lavvu, goahti, and the Finnish laavu. The main difference between a goahti and a lavvu is at the top. A lavvus poles come together at the top, while a goahtis poles stay separate. The turf version of a goahti replaces the canvas with wood covered with birch bark and then peat for a strong structure.

Lavvu (also called lávvu, láávu, kååvas, koavas, kota, or lavvo) is a structure built by the Sámi. It looks similar to a Native American tipi but is less vertical and more stable in strong winds. It allowed Indigenous cultures in the treeless plains of northern Scandinavia to follow their reindeer herds. It is still used as a temporary shelter by the Sámi and by others for camping.

Historical records describe the lavvu structure (sometimes called a kota). These structures share common features:

- The lavvu is supported by three or more evenly spaced forked poles that form a tripod.

- More than ten straight poles lean against the tripod, giving the structure its shape.

- The lavvu doesn't need stakes, guy-wire, or ropes for stability.

- Its shape and size depend on the number and size of the poles used.

- No center pole is needed to support this structure.

No historical record shows the Sámi using a single-pole structure called a lavvu. The description of this structure has been consistent since the 17th century.

A goahti (also gábma, gåhte, gåhtie, gåetie, or gamme in Norwegian) is a Sámi hut or tent. It can be covered with fabric, peat moss, or timber. The fabric-covered goahti looks much like a Sámi lavvu but is often slightly larger. In its tent form, the goahti is also called a 'curved pole' lavvu because its shape is more stretched out, while the lavvu is circular.

The inside pole structure includes:

- Four curved poles (8–12 feet long).

- One straight center pole (5–8 feet long).

- About a dozen straight wall-poles (10–15 feet long).

All pole sizes can vary.

The four curved poles bend to about a 130° angle. Two of these poles have a hole at one end, which are joined by the long center pole. The other two curved poles are joined at the other end of the long pole. When set up, this forms a four-legged stand with the long pole at the top center. With this structure standing 5 to 8 feet high, about ten or twelve straight "wall-poles" lean against it. The goahti covering, usually canvas today, is laid over the structure and tied down.

Modern Sámi Architecture

The Sámi Parliament building was designed by architects Stein Halvorsen & Christian Sundby. They won a competition in 1995, and the building opened in 2005. The government wanted a building that looked "dignified" and "reflected Sámi architecture."

Important projects include:

- The Sámi Parliament Building, Norway.

- Várjjat Sámi Musea (Varanger Sami Museum, VSM), Nesseby, Finnmark.

Samoa: Open Homes by the Sea

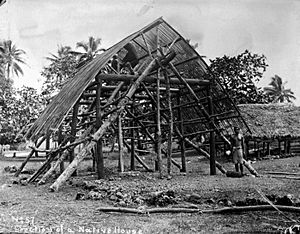

The architecture of Samoa is known for being open. Its design reflects the culture and life of the Samoan people. Building ideas are found in Samoan proverbs and stories, and they connect to other arts like boat building and tattooing. The spaces inside and outside traditional Samoan buildings are part of cultural ceremonies. Fale is the Samoan word for all types of houses. Traditional Samoan architecture is usually oval or circular, with wooden posts holding up a domed roof. There are no walls. The basic structure is a skeleton frame. Before Europeans arrived, a Samoan fale used no metal in its construction.

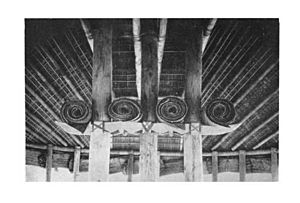

The fale is tied together with a braided rope called ʻafa. This rope is handmade from dried coconut fiber. The ʻafa is woven tightly in complex patterns around the wooden frame, holding the whole building together. Making enough afa for one house can take months. An ordinary traditional fale might use 30,000 to 50,000 feet of ʻafa. This lashing technique is a great architectural achievement of Polynesia. It was also used in boat building, where wood planks were 'sewn' together.

The shape of a fale, especially large meeting houses, creates physical and invisible areas. These areas are understood in Samoan custom and guide social interactions. The fale's use is closely linked to the Samoan social system, especially the Fa'amatai (chiefly system).

At formal gatherings, people sit cross-legged on mats around the fale, facing each other with an open space in the middle. The directions inside a fale (east, west, north, south) and the positions of the posts affect where chiefs sit based on their rank. They also show where orators stand to speak and where guests enter and sit. The space also defines where 'ava makers sit and the open area for exchanging cultural items.

The front of a Samoan house faces the main road. The floor is divided into sections: Tala luma (front side), tala tua (back), and tala (two ends). The middle posts, matua tala, are for leading chiefs. The side posts at the front, pou o le pepe, are for orators. The posts at the back, talatua, are for 'ava makers and others serving the gathering.

The area outside the fale is usually kept clear, either a grassy lawn or sand near the sea. The open area in front of large meeting houses, facing the main road, is called the malae. It's an important outdoor space for larger gatherings and ceremonies. The word "fale" is also used with other words to describe social groups or buildings, like falema'i (hospital, meaning "house of the ill").

The simplest fale types are called faleo'o. These are popular as eco-friendly beach accommodations for tourists. Every family in Samoa has a fale tele, the meeting house or "big house." The building site is called tulaga fale (place to stand).

The builders in Samoan architecture were also the architects. They belonged to an ancient guild of master builders, Tufuga fau fale. Tufuga means master craftsmen. Fau-fale means 'house builder'. There were also Tufuga for navigation and tattooing. Hiring a Tufuga fau fale involved special cultural customs.

The fale tele (big house) is the most important house. It's usually round and used for chief council meetings, family gatherings, funerals, or chief title ceremonies. The fale tele is always at the front of all other houses in a family complex. Houses behind it are living quarters, with an outdoor cooking area at the back. In front is an open area called a malae. The malae is a well-kept lawn or sandy area. It's an important cultural space for interactions between visitors and hosts.

The open design of Samoan architecture is also seen in how houses are arranged in a village. All fale tele are placed prominently at the front, sometimes forming a semicircle, usually facing the sea. Today, with modern materials, the fale tele is often rectangular, but the cultural uses of its spaces remain the same.

Traditionally, the afolau (long house) was a longer, oval-shaped fale used as a dwelling or guest house.

The faleo'o (small house) was traditionally long and an addition to the main house. It wasn't as strongly built and was always at the back of the main dwelling. Today, the term also means any small, simple fale that isn't the main house. They are popular as "grass huts" or beach fales for tourism, often raised on stilts with iron roofs. Families build a faleo'o next to their main house or by the sea for resting during the day or as extra sleeping space for guests.

The tunoa (cook house) is a simple, small structure, not really a house. Today, the cook house, called the umukuka, is at the back of the family area. All cooking is done there in an earth oven (umu) or pots over a fire. In most villages, the umukuka is a simple open shed with a few posts and an iron roof to protect the cooking area from weather.

Building a fale, especially a large fale tele, often involves the whole extended family and help from the village.

The Tufuga fai fale (master builder) oversees the project. Before building, the family prepares the site with lava, coral, sand, or stone. The Tufuga, his assistants, and family members cut timber from the forest. The main supporting posts, called poutu, are erected first. They vary in size and length depending on the house. They are usually 16 to 25 feet long and 6 to 12 inches wide, buried about four feet deep in the middle of the house.

Cross pieces of wood called so'a are attached to the poutu. The so'a extend to the outside of the fale and are fastened to other supports called la'au fa'alava.

The la'au fa'alava are horizontal pieces attached to wide strips of wood called ivi'ivi. The faulalo is a tubular piece of wood running around the house's circumference at the lower roof edge, supported by poulalo. The auau is one or more large pieces of wood resting on top of the poutu. Circular pieces of wood run around the house, spaced about two feet apart, from the faulalo to the top.

The poulalo are spaced about three to four feet apart and buried about two feet deep. They are about three to four inches wide and extend about five feet above the floor. Their height determines how high the lower roof edge is from the ground.

On the framework are many aso, thin timber strips (about half an inch by a quarter, 12 to 25 feet long). They extend from the faulalo to the ivi'ivi, spaced one to two inches apart. Further strips, paeaso, are attached at right angles. This divides the fale's roof into many small squares.

Most timber comes from family land forests. The heavy work of cutting and carrying timber is done by the builder's assistants, family members, and villagers. Main posts were often from the breadfruit tree (ulu). Long main rafters needed to be flexible, so coconut wood (niu) was chosen.

Common timbers used in Samoan houses:

- Posts (poutu and poulalo): ifi lele, pou muli, asi, ulu, talia, launini'u, and aloalovao.

- Fau: ulu, fau, niu, and uagani.

- Aso and paeso: niuvao, ulu, matomo, and olomea.

- The auau and talitali use ulu, and the so'a use both ulu and niu.

The completed, domed framework is covered with thatch (lau leaves), made by women. The best thatch uses dry sugarcane leaves. If not available, coconut palm leaves are used. Long, dry leaves are twisted over a three-foot length of lafo, then fastened with a thin coconut frond strip. These thatch sections are attached to the outside of the fale frame, starting at the bottom and working up. They overlap, creating a double layer of thatch.

Good quality thatch lasts about seven years. An ordinary house uses about 3000 thatch sections. To protect from sun, wind, rain, or curious eyes, 'Venetian blinds' called pola are hung from the fau around the house. These are mats woven from coconut fronds, about a foot wide and three feet long. Enough pola to reach from the ground to the top of the poulalo are tied together. They can be tied up or let down as needed. One string of these mats covers the space between two poulalo. They don't last long but are easy to replace. They offer good protection, and since they can be lowered in sections, the whole house is rarely closed up.

The natural foundations of a fale site are coral, sand, and lava, sometimes with a few inches of soil. This provides good drainage. The top layers of the floor are smooth pebbles and stones. When occupied, house floors are usually covered with native mats.

In Samoan mythology, a story explains why Samoan houses are round. It's about the god Tagaloa, also known as Tagaloalagi (Tagaloa of the Heavens).

According to historian Te'o Tuvale, in Tagaloalagi's time, Samoan houses varied in shape. This caused problems for builders. All carpenters met to decide on a uniform shape. They couldn't agree, so they asked Tagaloalagi. He pointed to the dome of Heaven and the horizon and said all future houses should be that shape. This is why Samoan houses are shaped like the heavens extending to the horizon. The coconut palm is also important in Samoan architecture, linked to the legend of Sina and the Eel.

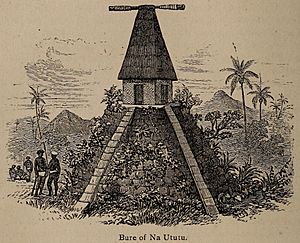

Fiji: Simple and Practical Designs

In old Fiji, village architecture was simple and practical. It met physical and social needs and provided safety. Houses were square with pyramid-shaped roofs. Walls and roofs were thatched. Useful plants were grown nearby. Each village had a meeting house and a Spirit house (Bure Kalou). The spirit house was built on a pyramid-like base of large stones and earth. It was also a square building with a long, pyramid-like roof, and scented plants were grown nearby.

Chiefs' houses had similar designs and were built higher than other homes. They had similar roofs to their subjects' houses but on a larger scale.

Modern Architecture in Fiji

With people arriving from Asia, their cultural architecture is now seen in Fiji's towns and rural areas, especially on the main islands of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu. Village structures today are similar but built with modern materials. Spirit houses (Bure Kalou) have been replaced by churches of various designs.

Early colonial Fiji's urban areas looked like British colonies from the 19th and 20th centuries. While some of this architecture remains, the urban landscape is changing rapidly with modern designs in business, industrial, and residential areas. Rural areas are changing much slower.

Palau: Important Meeting Houses

In Palau, there are many traditional meeting houses called bais or abais. In ancient times, every village had a bai because it was the most important building. At the start of the 20th century, over 100 bais still existed. In bais, governing elders sit along the walls according to their rank. A bai has no inner walls or furniture and is decorated with pictures of Palauan legends. Palau's oldest bai is Airai Bai, which is over 100 years old. Bais are featured on the Seal of Palau and the flag of Koror.

United States: Diverse Indigenous Styles

Traditional Architecture of Hawai'i

Hawai'ian architecture has different styles from various historical periods. The earliest form comes from ancient Hawaiʻi. This includes simple shelters for outcasts, huts for fishermen, homes for working-class people (makaʻainana), and grand thatched homes on raised basalt foundations for chiefs (aliʻi).

The way a simple grass shack was built in ancient Hawaiʻi showed who lived there. The patterns of dried plants and lumber could identify a person's social class, skill, trade, and wealth. Before British explorer James Cook arrived, Hawaiian architecture used symbols to show the religious importance of certain buildings. Feather standards called kahili and koa wood decorated with kapa cloth, crossed at the entrance of some homes (called puloʻuloʻu), showed places of aliʻi (nobility). Kiʻi (carved figures) inside basalt walls marked the homes of kahuna (priestly class).

Puebloan Architecture

Pueblo-style architecture looks like traditional Pueblo adobe buildings. Even if other materials like brick or concrete are used, builders make them look like adobe. They use rounded corners, uneven parapets (low walls at the edge of a roof), and thick, sloped walls. Walls are usually covered in stucco and painted in earth tones. Multi-story buildings often have stepped shapes, like those at Taos Pueblo. Roofs are always flat.

Common features include wooden roof beams called vigas that stick out. Sometimes these beams are just for looks. There are also "corbels," which are curved, often decorative, supports for the beams. Latillas are peeled branches or wood strips laid across the tops of vigas to create a base for the roof, usually supporting dirt or clay.

Philippines: The Bahay Kubo

The Bahay Kubo, also called Kamalig or Nipa Hut, is a type of stilt house found in most lowland cultures of the Philippines. It often represents Filipino culture, especially rural life.

While there's no single definition, and styles vary across the Philippines, similar conditions have led to common features. Most Bahay Kubo are raised on stilts, so you need ladders to enter the living area. This divides the house into three parts: the living area, the space underneath (called "Silong" in Tagalog), and the roof space (Bubungan).

The traditional roof of a Bahay Kubo is tall and steeply pitched, with long eaves. A tall roof allows warm air to rise, keeping the house cool even in hot weather. The steep pitch lets water flow off quickly during monsoon season, and the long eaves provide a sheltered space around the house when it rains. The steep roofs are why many Bahay Kubo survived the ash fall from the Mt. Pinatubo eruption, while more modern houses collapsed.

Raised on hardwood stilts, Bahay Kubo have a Silong (meaning "shadow") area underneath the living space. This area helps protect against floods and keeps pests like rats away. This space is often used for storage or raising farm animals and may or may not be fenced.

The main living area is designed to let in lots of fresh air and natural light. Smaller Bahay Kubo often have bamboo slat floors, which allow cool air to flow up from the silong. Some may not have a ceiling (kisame), so hot air can rise into the roof space and escape through vents.

The walls are always made of light materials like wood, bamboo rods, or bamboo mats called "sawali." These materials help keep the house cool in hot weather and warm in cold, wet seasons. The cube shape comes from how easy it is to build the walls first and then attach them to the wooden stilts. Building a Bahay Kubo is usually done in modules: stilts first, then floor frame, then wall frames, and finally, the roof.

Bahay Kubo typically have large windows to let in air and light. The most traditional are large awning windows held open by a wooden rod. Sliding windows are also common, made of plain wood or wood with Capiz shell frames, which let light in even when closed. In larger houses, small windows called Ventanillas (Spanish for "little window") might be placed underneath the main windows for extra air on hot days.

Some Bahay Kubo, especially those for long-term living, have a Batalan, a "wet area" that sticks out from one of the walls. It can be at the same level as the living area or at ground level. The Batalan might include a cooking and dishwashing area, a bathing area, and sometimes a toilet.

The walls of the living area are light, with posts, walls, and floors typically made of wood or bamboo. The thatched roof is often made from nipa, anahaw, or other local plants. The Filipino term "Bahay Kubo" literally means "cube house," describing its shape. The term "Nipa Hut," from the American colonial era, refers to the nipa or anahaw thatching.

Nipa huts were the native houses before the Spaniards arrived. They are still used today, especially in rural areas. Different groups have different designs, but all are stilt houses, similar to those in Indonesia, Malaysia, and other Southeast Asian countries. When the Spanish arrived, they introduced the idea of permanent communities with a church and government center. Builders adapted the Bahay Kubo's features to create "stone houses" (Bahay na Bato).

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |