Platypus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Platypus |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Platypus swimming in waters near Scottsdale, Tasmania | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

|

|

| Platypus range (red – native, yellow – introduced) |

|

| Synonyms | |

|

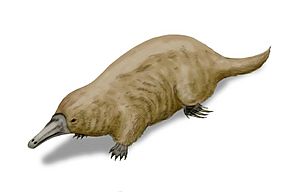

The platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus), sometimes called the duck-billed platypus, is a special kind of mammal that lives partly in water (semiaquatic). It lays eggs instead of giving birth to live young. You can only find it in eastern Australia, including Tasmania. The platypus is the only living member of its family, Ornithorhynchidae, and its group, Ornithorhynchus. However, some similar animals are known from fossils.

Along with the four types of echidna, the platypus is one of only five living monotremes. These are mammals that lay eggs. Like other monotremes, the platypus can find its food in cloudy water by sensing tiny electric fields. This is called electrolocation. It's also one of the few venomous mammals. Male platypuses have a spur on their back foot that can deliver a very painful venom.

When European scientists first saw a platypus in 1799, they were very confused. It looked like it had a duck's bill, a beaver's tail, and otter-like feet. Some even thought it was a fake animal made from different parts sewn together!

The platypus is important for studying evolutionary biology because of its unique features. It's also a famous symbol of Australia. Many Aboriginal peoples find it culturally important and used to hunt it for food. The platypus has been a national mascot and appears on the back of the Australian twenty-cent coin. It's also the symbol of the state of New South Wales.

People used to hunt platypuses for their fur. But since 1912, it has been a protected species in all states where it lives. Its population is not in huge danger, but it is sensitive to pollution. The IUCN lists it as a near-threatened species. However, a report in November 2020 suggested it should be listed as a threatened species under Australian law. This is because its habitat is being destroyed and its numbers are falling in all states.

Contents

Taxonomy and Naming

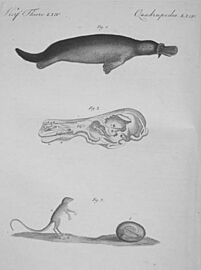

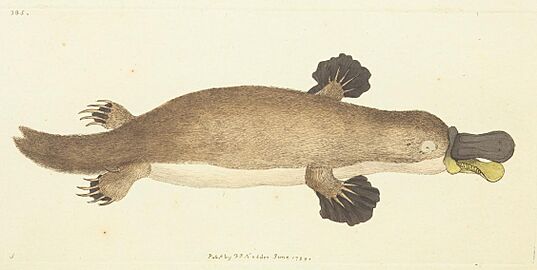

When Europeans first saw the platypus in 1798, a fur pelt and a drawing were sent to Great Britain. Captain John Hunter, the governor of New South Wales, sent them. At first, British scientists thought it was a trick. George Shaw, who wrote the first description in 1799, said it was hard to believe it was real. Robert Knox thought someone might have sewn a duck's beak onto a beaver-like body. Shaw even cut the dried skin with scissors to check for stitches!

The name "platypus" means 'flat-foot'. It comes from the Greek words platús (meaning 'broad, wide, flat') and poús (meaning 'foot'). Shaw first named it Platypus anatinus. But scientists soon found that the name Platypus was already used for a type of wood-boring beetle. So, Johann Blumenbach independently described it as Ornithorhynchus paradoxus in 1800. Later, it was officially named Ornithorhynchus anatinus.

There isn't one agreed-upon way to say "platypus" in plural. Scientists often say "platypuses" or just "platypus." Some people say "platypi," but this is not correct based on the Greek roots. Early British settlers called it names like "watermole" or "duckbill." Sometimes it's still called the "duck-billed platypus."

The scientific name Ornithorhynchus anatinus means 'duck-like bird-snout'. The first part, Ornithorhynchus, comes from Greek words meaning 'bird' and 'snout' or 'beak'. The second part, anatinus, comes from Latin and means 'duck-like'. The platypus is the only living member of its family, Ornithorhynchidae.

Physical Description

David Collins wrote about the new colony in Australia from 1788 to 1801. He described an "amphibious animal, of the mole species" with a drawing.

The platypus's body and its wide, flat tail are covered in thick, brown, glowing fur. This fur traps air to keep the animal warm. The fur is waterproof and feels like a mole's fur. The platypus stores fat in its tail, just like a Tasmanian devil. Its front feet have more webbing, which it folds up when walking on land to protect it. The long snout and lower jaw are covered in soft skin, forming its bill. Its nostrils are on top of the snout. Its eyes and ears are just behind the snout in a groove that closes when it dives underwater. Platypuses can make a low growl when bothered.

Their size changes a lot depending on where they live. They usually weigh from 0.7 to 2.4 kg (1.5 to 5.3 lb). Males are about 50 cm (20 in) long, while females are smaller, about 43 cm (17 in). This size difference doesn't seem to follow any weather patterns. It might be due to things like predators or human activity.

The platypus has a body temperature of about 32°C (90°F). This is lower than the 37°C (99°F) typical for most other mammals. Scientists think this is an adaptation to harsh environments.

Besides laying eggs, the platypus's body, development, and genes show some similarities to reptiles and birds. The platypus walks with its legs on the sides of its body, like a reptile, instead of underneath. Its genes might show a link between mammal and bird/reptile ways of determining sex.

Like all true mammals, the tiny bones that carry sound in the middle ear are fully inside the skull. But the outside opening of the ear is still at the base of the jaw. The platypus has extra bones in its shoulder, not found in other mammals. Like many other water animals, its bones are dense. This helps it sink and stay underwater.

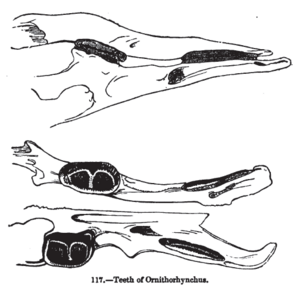

The platypus's jaw is built differently from other mammals. Its jaw-opening muscle is also unique. Young platypuses have three teeth in each jaw, but they lose them before or just after leaving their burrow. Adult platypuses have tough, keratin-covered pads instead of teeth. These pads help them grind their food.

Venom

Both male and female platypuses are born with spurs on their back ankles. But only the males' spurs can deliver venom. This venom is strong enough to kill small animals like dogs. It won't kill humans, but it can cause weeks of extreme pain. The area around the wound quickly swells. The pain can spread and last for days or even months.

The venom is mostly made of special proteins called defensin-like proteins (DLPs). These are made by the immune system. Three of these proteins are only found in platypuses. In other animals, defensins fight bacteria and viruses. But in platypuses, they are also used as venom against predators. The venom is made in glands in the male's legs. These glands are connected by a thin tube to a spur on each back leg. Female platypuses have small spur buds that don't grow. They also don't have working venom glands. Males produce more venom during breeding season. They might use it to show who is stronger.

Similar spurs are found on many ancient mammal groups. This suggests that having spurs was common among early mammals.

Electrolocation

Monotremes are the only mammals (besides the Guiana dolphin) known to use electroreception. The platypus's electroreception is the most sensitive of any monotreme. When it dives, the platypus closes its eyes, ears, and nose. It digs in the bottom of streams with its bill. Its electroreceptors find tiny electric currents made by the muscles of its prey. This helps it tell living things from non-living things. Experiments show that a platypus will even react to a fake shrimp if a small electric current passes through it.

The electroreceptors are in rows on the skin of its bill. Touch sensors are spread evenly across the bill. The part of the brain that handles electric senses is in the same area as the touch senses. Some brain cells get signals from both electric and touch sensors. This suggests the platypus feels electric fields like touches. These bill sensors are very important in the platypus's brain map. This is similar to how human hands are very important in our brain map.

The platypus can tell the direction of an electric source. It might do this by comparing how strong the electric signal is across its bill. It also moves its head from side to side while hunting, which helps. It might even be able to guess how far away moving prey is by the time difference between electric and touch signals.

Monotremes using electrolocation to hunt in murky water might be linked to them losing their teeth. The extinct Obdurodon also used electroreception. But unlike the modern platypus, it hunted near the ocean surface.

Eyes

Recent studies suggest that the platypus's eyes are more like those of Pacific hagfish or lampreys than most other four-legged animals. Its eyes also have special cells called double cones, which most mammals don't have.

Even though the platypus's eyes are small and not used underwater, some features show that vision was important for its ancestors. The front of its eye and the nearby lens surface are flat. But the back of the lens is very curved. This is like the eyes of other water mammals such as otters. A group of cells in the retina (at the back of the eye) is important for seeing with both eyes. This suggests that vision used to help them hunt. However, their eyesight isn't good enough for hunting now. These features suggest the platypus has adapted to living in water and being active at night. It developed its electric sensing system, but its vision became less important.

Biofluorescence

In 2020, scientists found that platypus fur glows bluish-green under black light. This is called biofluorescence.

Habitat and Behavior

The platypus lives partly in water. It makes its home in small streams and rivers across a large area. This area stretches from the cold highlands of Tasmania and the Australian Alps to the tropical rainforests of coastal Queensland. It can be found as far north as the base of the Cape York Peninsula.

We don't know much about its numbers further inland. It was thought to be gone from mainland South Australia. The last sighting there was in 1975. In the 1980s, John Wamsley started a platypus breeding program at Warrawong Wildlife Sanctuary. This sanctuary later closed. But in 2017, there were some unconfirmed sightings near the sanctuary. In October 2020, a nesting platypus was filmed inside the recently reopened sanctuary.

There is a group of platypuses on Kangaroo Island that were brought there in the 1920s. About 150 platypuses are said to live in the Rocky River area of Flinders Chase National Park. During the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season, large parts of the island burned. This greatly harmed the wildlife. But recovery teams worked to fix their habitat. By April 2020, several platypuses had been seen.

The platypus is no longer found in the main Murray–Darling Basin. This might be because the water quality has gotten worse from land clearing and irrigation. Along the rivers near the coast, where they live is hard to predict. They are missing from some healthy rivers but present in some polluted ones.

In zoos, platypuses have lived up to 17 years. Wild platypuses have been found again when they were 11 years old. Not many adult platypuses die in the wild. Natural predators include snakes, water rats, goannas, hawks, owls, and eagles. There are fewer platypuses in northern Australia. This might be because of crocodiles eating them. When red foxes were brought to Australia in 1845 for hunting, they might have also affected platypus numbers. The platypus is usually active at night or at dawn and dusk. But it can be active on cloudy days. It lives in rivers and along their banks. It finds food and digs burrows there. A platypus might travel up to 7 km (4.3 mi). A male's home area might overlap with three or four females.

The platypus is a great swimmer and spends a lot of time in the water looking for food. It swims in a unique way for a mammal. It pushes itself forward by moving its front feet one after the other. Its webbed back feet are held against its body and only used for steering, along with its tail. It can keep its body temperature of about 32°C (90°F) while looking for food for hours in water below 5°C (41°F). Dives usually last about 30 seconds. They can hold their breath for about 40 seconds. They spend 10 to 20 seconds on the surface between dives.

The platypus rests in a short, straight burrow in the riverbank. The burrow is about 30 cm (12 in) above the water. Its oval entrance is often hidden under roots. It can sleep up to 14 hours a day after half a day of diving.

Diet

The platypus is a carnivore, meaning it eats meat. It feeds on worms, insect larvae, freshwater shrimp, and yabby (crayfish). It digs these out of the riverbed with its snout or catches them while swimming. It carries its prey to the surface in special cheek-pouches before eating it. A platypus eats about 20% of its own weight every day. This means it spends about 12 hours daily looking for food.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Platypuses have one breeding season between June and October. This can change a little depending on the area. Scientists think that one male might mate with several females. Females are thought to be able to have babies when they are two years old. They have been seen breeding when they are over nine years old. The male platypus does not help with nesting. He lives in his own burrow all year. After mating, the female builds a deep, long nesting burrow, up to 20 m (66 ft) long. She gathers fallen leaves and reeds with her tail. She drags them into the burrow to make the tunnel floor soft and to line the nest at the end.

The female platypus has two ovaries, but only the left one works. She lays one to three (usually two) small, leathery eggs. They are about 11 mm (0.43 in) across and a bit rounder than bird eggs. The eggs grow inside her for about 28 days. Then, they are incubated outside for only about 10 days. (A chicken egg, for example, spends about one day inside and 21 days outside.) The female curls around the eggs to keep them warm. The eggs develop in three stages. In the first stage, the baby platypus has no working organs and gets food from the yolk sac. In the second stage, its fingers and toes grow. In the last stage, a special "egg tooth" appears. At first, European scientists could not believe that the female platypus laid eggs. But this was finally confirmed in 1884.

Baby platypuses are called "puggles." When they hatch, they are helpless, blind, and have no fur. Their mother feeds them milk. The platypus's mammary glands don't have nipples. Instead, milk comes out through pores in the skin. The milk collects in grooves on the mother's belly, and the puggles lap it up. After they hatch, the babies drink milk for three to four months.

While incubating and feeding her young, the mother only leaves the burrow for short times to find food. She leaves several thin dirt plugs along the burrow. This might protect the young from predators. When she returns, pushing past these plugs squeezes water from her fur, keeping the burrow dry. After about five weeks, the mother starts spending more time away from her young. At around four months, the young platypuses come out of the burrow. A platypus is born with teeth, but these fall out very early. Then it uses the tough, horny plates to grind food.

Evolution

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| How the platypus is related to other mammals |

Scientists didn't understand the platypus and other monotremes very well for a long time. Some old ideas from the 1800s, like that monotremes were "less developed" or like reptiles, still exist. In 1947, William King Gregory thought that placental mammals and marsupials split off first. Then, monotremes and marsupials split. But later research and fossil finds showed this was wrong. Modern monotremes are actually survivors from a very early branch of the mammal family tree. Marsupials and placental mammals branched off later. Scientists think platypuses and echidnas separated about 19 to 48 million years ago.

The oldest fossil of a modern platypus is about 100,000 years old. Extinct monotremes like Teinolophos and Steropodon were once thought to be close relatives. But now they are seen as more basic, older types of monotremes. The fossilized Steropodon was found in New South Wales. It was a jawbone with three molar teeth. Modern adult platypuses don't have teeth. This fossil is about 110 million years old, making it the oldest mammal fossil found in Australia. Unlike the modern platypus, Teinolophos did not have a beak.

Monotrematum sudamericanum, another fossil relative of the platypus, was found in Argentina. This shows that monotremes lived on the supercontinent of Gondwana. At that time, South America and Australia were connected through Antarctica. A fossilized tooth of a giant platypus, Obdurodon tharalkooschild, was found. It was 5 to 15 million years old. Based on the tooth, this animal was 1.3 meters (4.3 ft) long, making it the biggest platypus ever found.

Because the platypus split off from other mammals so early, and there are few living monotreme species, it is often studied in evolutionary biology. In 2004, scientists found that the platypus has ten sex chromosomes. Most other mammals have only two (XY). These ten chromosomes form five unique pairs (X1Y1X2Y2X3Y3X4Y4X5Y5 in males). One of the platypus's X chromosomes is very similar to the Z chromosome in birds. The platypus's genes also have both reptile and mammal genes related to egg fertilization. Scientists published a draft of the platypus's genetic code in 2008. It showed both reptile and mammal parts. It also had two genes previously found only in birds, amphibians, and fish. More than 80% of the platypus's genes are common to other mammals whose genes have been studied. A more complete genetic map was published in 2021.

Conservation Efforts

Status and Threats

Except for its disappearance from South Australia, the platypus still lives in the same general areas as before Europeans settled Australia. However, human changes to its habitat have caused local changes and broken up its living areas. We don't know how many platypuses there used to be, and it's hard to count them now. But their numbers are thought to have gone down. Still, as of 1998, they were considered common in most of their range. People hunted them a lot for their fur until the early 1900s. The species became legally protected starting in Victoria in 1890 and across Australia by 1912. But until about 1950, they were still at risk of drowning in fishing nets.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature changed its status to "near threatened" in 2016. The species is protected by law. But the only state where it is listed as endangered is South Australia. In November 2020, it was suggested that the platypus should be listed as a vulnerable species across all states. Victoria officially listed it as vulnerable on January 10, 2021.

Habitat Destruction

The platypus is not thought to be in immediate danger of dying out. This is because conservation efforts have worked. But it could be harmed by changes to its habitat from dams, irrigation, pollution, and fishing nets. Less water flow and lower water levels from droughts and taking water for homes and farms are also a threat. The IUCN lists the platypus as "Near Threatened" based on a 2016 assessment. At that time, it was estimated that numbers had dropped by about 30 percent since European settlement. The animal is listed as endangered in South Australia.

Scientists have been worried for years that the decline is worse than thought. In January 2020, researchers from the University of New South Wales showed that the platypus is at risk of extinction. This is due to less water, land clearing, climate change, and severe drought. The study predicted that platypus numbers would drop by 47–66% over 50 years. This would cause "extinction of local populations across about 40% of the range." With climate change predictions for 2070, less habitat due to drought would lead to 51–73% fewer platypuses within 50 years. These predictions suggest the species would be classified as "Vulnerable." The authors said that national conservation efforts are needed. These could include more surveys, tracking changes, reducing threats, and improving river management. This would help make sure platypus habitats are healthy.

A report in November 2020 by scientists from the University of New South Wales found that platypus habitat in Australia had shrunk by 22 percent in the last 30 years. They suggested that the platypus should be listed as a threatened species. The biggest drops in population were in New South Wales, especially in the Murray–Darling basin.

Disease

Platypuses usually don't get many diseases in the wild. However, as of 2008, there was concern in Tasmania about a disease caused by a fungus called Mucor amphibiorum. This disease (called mucormycosis) only affects Tasmanian platypuses. It had not been seen in platypuses on mainland Australia. Affected platypuses can get skin sores or ulcers on different parts of their bodies. Mucormycosis can kill platypuses. Death happens from other infections and by affecting the animals' ability to stay warm and find food well.

Wildlife Sanctuaries

Many people around the world learned about the platypus in 1939. That's when National Geographic Magazine published an article about studying and raising it in captivity. Raising them in captivity is hard. Only a few young platypuses have been successfully raised since then. This happened notably at Healesville Sanctuary in Victoria. David Fleay was a key person in these efforts. He built a "platypusary" (a fake stream in a tank) at Healesville Sanctuary. Platypuses successfully bred there in 1943. In 1972, he found a dead baby platypus, about 50 days old, that was likely born in captivity. This was at his wildlife park in Queensland. Healesville had success again in 1998 and 2000 with a similar stream tank. Since 2008, platypuses have bred regularly at Healesville. This includes platypuses born in captivity that then bred themselves. Taronga Zoo in Sydney bred twins in 2003 and again in 2006.

Captivity

As of 2019, the only platypuses in captivity outside of Australia are at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park in California. Three attempts were made to bring them to the Bronx Zoo in 1922, 1947, and 1958. Of these, only two of the three animals brought in 1947, Penelope and Cecil, lived longer than eighteen months.

Human Interactions

Usage

Aboriginal Australians used to hunt platypuses for food. Their fatty tails were especially nutritious. After colonization, Europeans hunted them for fur from the late 1800s until 1912, when it was made illegal.

See also

In Spanish: Ornitorrinco para niños

In Spanish: Ornitorrinco para niños

- Henry Burrell

- Ellis Joseph

- Fauna of Australia