Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Anglo-Spanish War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War and the Anglo-Spanish Wars | |||||||

English ships and the Spanish Armada, 8 August 1588 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

The Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) was a long conflict between Spain and England. It was never officially declared. This war involved many English privateers, who were like legal pirates, attacking Spanish ships. It also included several battles across different parts of the world. The war started when England sent soldiers to the Spanish Netherlands in 1585. These troops, led by the Earl of Leicester, supported the Dutch rebels who were fighting against Spanish rule.

England had some big wins, like a victory at Cádiz in 1587 and defeating the famous Spanish Armada in 1588. However, they also faced tough losses. These included the English Armada (1589), the Drake–Hawkins expedition (1595), and the Essex–Raleigh expedition (1597). Spain also sent three more armadas against England and Ireland in 1596, 1597, and 1601. But these Spanish fleets also failed, mostly because of bad weather.

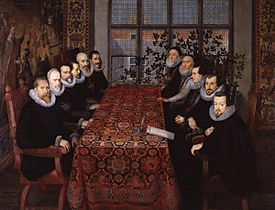

The war reached a stalemate around the year 1600. Battles continued in the Netherlands, France, and Ireland. The conflict finally ended with the Treaty of London (1604). This treaty was agreed upon by Philip III of Spain and the new English king, James I. In the treaty, England and Spain promised to stop interfering in the Spanish Netherlands and Ireland. The English also agreed to stop their privateering attacks on Spanish ships.

Why the War Started

In the 1560s, Philip II of Spain faced growing religious problems. Many people in his lands, especially in the Low Countries, were becoming Protestant. As a strong supporter of the Catholic Church, Philip wanted to stop this Protestant movement. This led to a major rebellion in 1566, known as the Dutch Revolt.

At the same time, relations with Elizabeth I of England got worse. Elizabeth had brought back royal control over the Church of England in 1559. Catholics saw this as going against the Pope's power. English Protestants wanted to help the Dutch rebels against Philip, which made things even more tense. Both sides also supported different groups in the religious conflicts happening in France.

| Opposing Monarchs |

|---|

|

|

Trade disagreements also added to the problems. English sailors, like Sir John Hawkins, started trading with Spanish colonies in the West Indies in 1562. Spain complained this was smuggling, but Elizabeth quietly supported it. In 1568, a Spanish attack surprised Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake at the Battle of San Juan de Ulúa. Several English ships were captured or sunk. This event made relations between England and Spain much worse.

Drake and Hawkins then increased their privateering to break Spain's control over Atlantic trade. Francis Drake even sailed around the world between 1577 and 1580. He raided Spanish ports and captured valuable ships, including the treasure galleon Nuestra Señora de la Concepción. When news of his adventures reached Europe, Elizabeth's relationship with Philip got even worse.

After 1580, England supported António, Prior of Crato, who was fighting Philip II for the throne of Portugal. In return, Philip supported the Catholic rebellion in Ireland against Elizabeth's religious changes. Both Philip's and Elizabeth's attempts to help opposing groups failed.

In 1584, Philip signed a deal with the Catholic League of France. This was to defeat the Protestant forces in the French Wars of Religion. In the Spanish Netherlands, England had secretly supported the Dutch Protestants who were fighting for independence from Spain. In 1584, the Prince of Orange was killed, which caused alarm and a power gap. The next year, Spanish forces captured Antwerp. This made Elizabeth worried that Spain would take over the Netherlands and then threaten England.

So, England signed the Treaty of Nonsuch. Elizabeth agreed to send soldiers, horses, and money to the Dutch. She did not want to rule the Dutch lands herself. In return, the Dutch gave England control of four "Cautionary Towns" where English troops were stationed. Philip saw this as England openly declaring war on his rule in the Netherlands.

The War Begins

The Anglo-Spanish War officially started in 1585. This happened after Spain seized English merchant ships in its harbors. In response, England's government allowed a campaign against the Spanish fishing industry. This took place in Newfoundland and off the Grand Banks. This campaign was a big success. It also led to England's first long-term activities in the Americas. In August, England joined the Eighty Years' War. They fought alongside the Dutch United Provinces, who had declared their independence from Spain. That same year, the English set up their first settlement in the New World, the short-lived Roanoke Colony.

Queen Elizabeth ordered Sir Francis Drake to attack Spanish lands in the New World. This was a kind of first strike. Drake sailed in October and in January 1586, he captured and looted Santo Domingo. The next month, they did the same at Cartagena de Indias. In May, they sailed north to raid St. Augustine in Florida. When Drake returned to England in July, he was a national hero. In Spain, this news was a disaster. It made King Philip even more determined to invade England.

Meanwhile, Thomas Cavendish set sail with three ships on July 21, 1586. His goal was to raid Spanish settlements in South America. Cavendish attacked three Spanish towns and captured or burned thirteen ships. Among these was a very rich 600-ton treasure galleon called Santa Ana. This was the biggest treasure haul ever taken by the English. Cavendish sailed around the world, returning to England on September 9, 1588.

Fighting in the Netherlands (1585–1587)

Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, went to the United Provinces in 1585. He accepted the offer to govern the United Provinces. However, Queen Elizabeth was very angry about this. She had said she did not want to rule the Dutch. An English army of hired soldiers had been there since the war began. It was led by Sir John Norreys. Their combined forces were too small and lacked money. They faced one of Europe's strongest armies, led by the famous Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma.

During the siege of Grave the next year, Dudley tried to help the town. But the Dutch commander, Hadewij van Hemert, surrendered the town to the Spanish. Dudley was furious and had van Hemert executed, which shocked the Dutch. The English then had some successes, taking Axel in July and Doesburg the next month. However, Dudley's poor handling of relations with the Dutch made things worse. His political power weakened, and so did the military situation.

Outside Zutphen, an English force was defeated. The famous poet Philip Sidney was badly wounded and later died. This was a huge blow to English morale. Zutphen and Deventer were betrayed by Catholic traitors, William Stanley and Rowland York. This further damaged Leicester's reputation. Finally, Sluis, with a mostly English army, was surrounded and captured by the Duke of Parma in June 1587. This happened after the Dutch refused to help. This led to both Leicester and the Dutch blaming each other.

Leicester soon realized how bad his situation was and asked to be called back. He resigned as governor. His time in charge had been a military and political failure, and he lost all his money. After Leicester left, the Dutch chose Count Maurice of Nassau, the Prince of Orange's son, as their new leader. At the same time, Peregrine Bertie took over the English forces in the Netherlands.

The Spanish Armada's Attack

On February 8, 1587, Mary, Queen of Scots was executed. This made Catholics across Europe very angry. In response, Philip II promised to invade England. He wanted to put a Catholic ruler on the English throne. In April 1587, Philip's plans faced a problem. Francis Drake burned 37 Spanish ships in the harbor of Cádiz. Because of this, the invasion of England had to be delayed for over a year.

On July 29, Philip got permission from the Pope to overthrow Elizabeth. She had been removed from the church by Pope Pius V. Philip gathered a fleet of about 130 ships, with 8,000 soldiers and 18,000 sailors. To pay for this, Pope Sixtus V allowed Philip to collect special taxes. The Pope also promised more money if the Spanish reached English soil.

On May 28, 1588, the Armada, led by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, sailed for the Netherlands. There, it was supposed to pick up more troops for the invasion of England. As the Armada sailed through the English Channel, the English navy fought them. The English, led by Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham, and Francis Drake, attacked the Spanish. They fought from Plymouth to Portland and then to the Solent. This stopped the Spanish from taking any English harbors.

The Spanish were forced to go to Calais. While they were anchored there in a defensive shape, the English used fire ships. These were ships set on fire and sent into the Spanish fleet. This broke up their formation and scattered the Spanish ships. In the next Battle of Gravelines, the English navy attacked the Armada. They forced it to sail north into more dangerous, stormy waters for the long trip home. As they sailed around Scotland, the Armada suffered terrible damage and lost many lives due to the storms. When they got near the west coast of Ireland, more bad weather pushed ships ashore or wrecked them. Many sailors also died from disease. The fleet finally limped back to port.

Philip's invasion plans failed partly because of bad weather and his own mistakes. Also, the clever defenses of the English navy and their Dutch allies won the day. The failure of the Armada gave English sailors valuable experience at sea. The English could continue their privateering against Spain. They also kept sending troops to help Philip II's enemies in the Netherlands and France. However, these efforts did not bring many clear rewards. One important result was that the Armada's failure was seen as a sign that God supported the Protestant Reformation in England. A medal celebrating the English victory had the words Flavit יהוה et Dissipati Sunt on it. This means "Yahweh blew and they were scattered."

-

The Battle of Gravelines, August 8, 1558, by Nicholas Hilliard

-

The flagship of Admiral Medina Sidonia (also known as Cadiz), the San Martin, is attacked off the coast of Dover from the left by the English Rainbow and from the right by the Dutch Gouden Leeuw, Dover, August 8, 1588

The English Armada

In 1589, an English counter-armada was prepared. It was led by Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Norris. It had three main goals:

- Destroy the damaged Spanish fleet, which was being repaired in northern Spain.

- Land in Lisbon, Portugal, and start a rebellion against King Philip II. They wanted to put Dom António on the Portuguese throne.

- Take the Azores if possible. This would create a permanent base and allow them to capture the incoming Spanish treasure fleet.

This mission was funded like a business, so Drake had investors to please. Instead of following the Queen's orders, he looked for plunder and money. He started by surprising Coruña on May 4. The lower town was captured and looted, and many merchant ships were seized. Norris then won a small victory over a Spanish relief force. However, when the English attacked the main fort, they were pushed back with heavy losses. Also, Spanish naval forces captured several English ships.

Two weeks later, the English left Coruña, having failed to capture it. They sailed towards Lisbon and landed on May 26. But due to poor planning (they had few siege cannons), lack of teamwork, and hunger, they also failed to take Lisbon. The expected uprising by Portuguese loyal to Crato never happened. With Portuguese and Spanish reinforcements arriving, the English had to retreat. They sailed North, throwing hundreds of dead bodies overboard along the way. Drake then looted and burned Vigo.

Young William Fenner, who had come from England with 17 supply ships, got separated from the fleet after a storm. He ended up heading towards the Madeira islands. The next day, seven more English ships joined him. They took the island of Porto Santo and restocked their supplies. Unable to find the rest of the fleet, they sailed for England. Drake tried to sail towards the Azores but could not sail against the wind. With more and more sickness and deaths, he gave up and limped back to Plymouth. Spanish ships harassed him almost the entire way.

None of the goals were achieved. The chance to strike a major blow against the weakened Spanish Navy was lost. This expedition used up a lot of England's money, which Queen Elizabeth had carefully saved. Its failure was so embarrassing that England barely mentions it even today. Because of this lost chance, Philip was able to rebuild his navy the very next year. He sent 37 ships with 6,420 men to Brittany. There, they set up a base of operations. The English and Dutch failed to stop the Spanish treasure fleets, even with many soldiers. So, Spain remained the most powerful country in Europe for several more decades.

Dutch Revolt Continues (1588–1598)

After the Spanish Armada was defeated, the Duke of Parma's army stopped its invasion plans. In the autumn, Parma moved his forces north towards Bergen op Zoom. He then tried to surround the English-held town with a large army. However, the English used a clever trick and managed to push back the Spanish. Parma had to retreat with heavy losses, which boosted both Dutch and English spirits. The next year, Bertie, following orders from Elizabeth I, went to France with an army. They helped the Protestants fight against the Catholic League. Sir Francis Vere then took command of the English forces. He stayed in this position for fifteen campaigns, with almost constant success.

In 1590, an Anglo-Dutch force led by Maurice and Vere launched a campaign to take Breda. A small attack force hid in a peat barge. They then launched a successful surprise attack that captured the city. Spanish forces were busy in France supporting the Catholic League, as well as in the Low Countries. Maurice was able to take advantage of this. He began a slow reconquest of the Netherlands, which the Dutch called the 'Ten glorious years'. Soon after Breda, the Anglo-Dutch forces retook Zutphen and Deventer. This restored English pride after their earlier betrayals. After defeating the Spanish under the Duke of Parma at Knodsenberg in 1591, the army gained new confidence. By this time, English troops made up almost half of the Dutch army.

The reconquest continued. Hulst, Nijmegen, Geertruidenberg, Steenwijk, and Coevorden were all captured within the next two years. In 1593, a Spanish attempt to recapture Coevorden failed. The Anglo-Dutch forces under Maurice and Vere relieved the town in the spring of 1594. Finally, the capture of Groningen in the summer of 1594 forced the Spanish army out of the northern provinces. This led to the full return of the seven provinces to Dutch control.

After these successes, Elizabeth saw the high confidence in her army. She renewed the treaty with the Dutch in 1595. English troops, highly praised by the Dutch, were kept at about 4,000 men. The Dutch would pay for them, and the Queen would also be repaid for her expenses until peace was made.

In 1595, Maurice's campaign restarted to retake cities in the Twente region from the Spanish. This was delayed after Huy was surrounded in March, but Maurice could not stop its fall. When Maurice did attack, an attempt to take Grol in July failed. A Spanish force under 90-year-old veteran Cristóbal de Mondragón relieved the city. Maurice then tried to attack Rheinberg in September, but Mondragon defeated this move. Maurice then had to cancel further planned attacks. Most of his English and Scottish troops were pulled out to join the attack on Cadiz. Under their new commander, the Archduke of Austria, the Spanish took advantage of this break. They recaptured Hulst the next year. This led to a long stalemate in the campaign and delayed the reconquest.

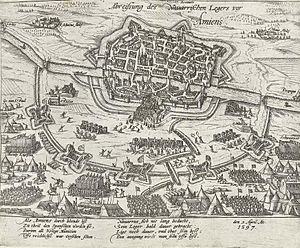

By 1597, Spain's financial problems and the war in France gave the Anglo-Dutch an advantage. At the Battle of Turnhout, a Spanish force was surprised and defeated. Vere and the Earl of Leicester fought especially well. With the Spanish busy with the siege of Amiens in France, Maurice launched an attack in the summer. This time, both Rhienberg and Greonlo were taken by the Dutch. This was followed by the capture of Bredevoort, Enschede, Ootsmarsum, Oldenzaal, and finally Lingen by the end of the year. The success of this attack meant that most of the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands had been retaken by the Dutch Republic. A strong barrier had been created along the Rhine river.

In November 1588, Philip II ordered 21 new, large galleons to be built. Most were built in Spanish ports. Philip then set up a naval base in Brittany. This base threatened England. It also allowed Spain to create a strong convoy system and a better spy network. This made it hard for English ships to attack the Spanish treasure fleet in the 1590s. A good example is when the English squadron, led by Effingham, was pushed back near the Azores in 1591. They had planned to ambush the treasure fleet. In this battle, the Spanish captured the English flagship, the Revenge, after its captain, Sir Richard Grenville, fought bravely. Throughout the 1590s, large convoy escorts helped Spain ship three times more silver than in the previous decade.

English merchant privateers, also known as Elizabeth's Sea Dogs, had more mixed success. In the three years after the Spanish Armada was defeated, they captured over 300 Spanish ships. These were worth more than £400,000. English nobles paid for their own expeditions, and even Elizabeth herself invested. The Earl of Cumberland led several expeditions. Some made a profit, like his Azores Voyage in 1589. Others failed due to bad weather, and his 1591 voyage ended in defeat.

Cumberland, with Sir Walter Raleigh and Martin Frobisher, combined their money and power. This led to the most successful English naval expedition of the war. Off Flores island in 1592, the English fleet captured a large Portuguese ship, the Madre de Deus. They also outsmarted a Spanish fleet. The money from this expedition was almost half of England's yearly royal income. Elizabeth made 20 times her investment back. These riches made the English very excited about this profitable trade.

Raleigh himself went on an expedition in 1595 to find the mythical city of El Dorado. During this trip, the English looted the Spanish settlement of Trinidad. Raleigh, however, exaggerated how much wealth he found when he returned to England. Another expedition, led by Amyas Preston and George Somers, supported Raleigh. This Preston Somers expedition to South America was famous for a daring land attack that captured Caracas.

Many expeditions were paid for by famous London merchants, especially John Watts. An expedition Watts funded to Portuguese Brazil, led by James Lancaster, captured and looted Recife and Olinda. This was very profitable. In response to English privateering, the Spanish navy used "Dunkirkers". These were privateers who attacked English shipping and fishing in the unprotected seas around England.

The most successful English privateer was Christopher Newport, funded by Watts. In 1590, Newport raided the Spanish West Indies. In a battle, he defeated an armed Spanish convoy but lost his right arm. Despite this, Newport continued his ventures. The blockade of Western Cuba in 1591 was the most successful English privateering trip of the war. Both Drake and Hawkins died of disease on a later expedition in 1595–96. This was a major setback. The English lost many soldiers and ships, even though they won some small battles.

In August 1595, a Spanish naval force from Brittany led by Carlos de Amésquita landed in Cornwall. They raided and burned Penzance and nearby villages.

In the summer of 1596, an Anglo-Dutch expedition, led by Elizabeth's favorite, the Earl of Essex, attacked Cádiz. This caused great damage to the Spanish fleet. The city was left in ruins, and a planned Spanish attack on England was delayed. The allies could not capture the treasure. The Spanish commander had time to burn the treasure ships in port, sending the treasure to the bottom of the harbor. It was later recovered. Even though they failed to get the treasure fleet, the attack on Cádiz was celebrated as a national victory, like the defeat of the Spanish Armada. For a while, Essex was as popular as Elizabeth herself.

Instead of controlling and taxing its people, the English crown competed with them for private profit. It did not succeed at this, as the big naval expeditions were mostly unprofitable. The last major English naval expedition was in 1597. It was led by the Earl of Essex and known as the Islands Voyage. The goal was to destroy the Spanish fleet and stop a treasure fleet in the Azores. Neither goal was achieved, and the expedition was a costly failure. Essex was scolded by the Queen for not protecting the English coast.

While the war was a big drain on England's money, it was very profitable for some English privateers. In the final years, English privateering continued, even as Spanish navy convoys got stronger. Cumberland's last expedition in 1598 to the Caribbean led to the capture of San Juan. He succeeded where Drake had failed. Newport attacked Tobasco in 1599, while William Parker successfully raided Portobello in 1601. In 1603, Christopher Cleeve attacked Santiago de Cuba. In the last raid of the war, Newport looted Puerto Caballos. Finally, just days before the peace treaty was signed in August 1604, future admiral Antonio de Oquendo defeated and captured an English privateer in the Gulf of Cádiz.

By the end of the war, English privateering had severely damaged Spanish merchant shipping. The most famous privateers often attacked fishing boats or small, less valuable ships. However, many Spanish ships were captured. Nearly 1,000 were taken by the war's end. On average, they were worth about £100,000-£200,000 each year of the war. For every Spanish ship brought back, another was burned or sunk. The presence of so many English privateers also stopped some Spanish merchant ships from sailing. This led to much Spanish and Portuguese trade being carried on Dutch and English ships, which created new competition. Still, throughout the war, Spain's important treasure fleets were kept safe by their convoy system.

Dutch Revolt Continues (1598-1604)

In 1598, the Spanish, led by Francisco Mendoza, retook Rheinberg and Meurs. This was part of a campaign known as the Spanish winter of 1598-99. Mendoza then tried to take Bommelerwaard island. But the Dutch and English, under Maurice, stopped him and defeated him at Zaltbommel. Mendoza retreated, and this defeat caused chaos in the Spanish army. Many soldiers rebelled and deserted.

The next year, the Dutch government saw the Spanish army's problems. They decided it was time to focus the war on Catholic Flanders. Despite a big disagreement between Maurice and his advisor, the Dutch and a large group of English soldiers under Francis Vere reluctantly agreed. They used Ostend (still held by the Dutch) as a base to invade Flanders. Their goal was to conquer the privateer stronghold city of Dunkirk. In 1600, they advanced toward Dunkirk. In a major battle, the Anglo-Dutch forces defeated the Spanish army at the Battle of Nieuwpoort. The English played a big part in this victory. However, Dunkirk was never attacked. Disagreements in the Dutch command meant that taking Spanish-occupied cities in the rest of the Republic became the priority. Maurice's force pulled back, leaving Vere to command Ostend as a Spanish siege was coming.

With the siege of Ostend underway, Maurice then attacked the Rhine frontier in the summer of 1600. Rheinberg and Meurs were taken back from the Spanish again. However, an attempt on s'Hertogenbosch failed during the winter. At Ostend in January 1602, after getting more troops, Vere faced a huge Spanish attack. This was planned by the Archduke Albert. In fierce fighting, the attack was pushed back with heavy losses. Vere left the city soon after and joined Maurice in the field. Albert, who was criticized for his tactics, was replaced by the talented Ambrogio Spinola. The siege dragged on for another two years. The Spanish tried to take Ostend's strong points in a costly war of attrition.

Around the same time, Maurice continued his campaign. Grave was retaken, but Vere was badly wounded during the siege. The Dutch and English tried to relieve Ostend in mid-1604. But instead, the inland port of Sluis was surrounded and captured. Soon after, the Ostend army finally surrendered. The siege had lasted nearly four years and cost thousands of lives. For the Spanish, it was a victory that cost too much.

Fighting in France

Normandy became a new front in the war. It also brought the threat of another invasion attempt across the English Channel. In 1590, the Spanish landed a large force in Brittany. They helped the French Catholic League, pushing English and Protestant forces out of much of the area. Henry IV became Catholic in 1593. This gained him wide French support for his claim to the throne, especially in Paris. He had unsuccessfully besieged Paris in 1590. In 1594, Anglo-French forces ended Spanish hopes of using the large port of Brest to invade England. They did this by capturing Fort Crozon.

The French Wars of Religion turned more and more against the hardline Catholic League. In 1596, France, England, and the Dutch signed the Triple Alliance. Elizabeth sent another 2,000 troops to France after the Spanish took Calais. In September 1597, Anglo-French forces under Henry retook Amiens. This happened just six months after the Spanish took the city. It stopped a series of Spanish victories. In fact, early peace talks between France and Spain had already begun before the battle. The Catholic League hardliners were losing public support in France. Henry's conversion to Catholicism and his military successes boosted his popularity. Also, Spain's finances were in trouble because of fighting wars in France, the Netherlands, and against England.

So, a very ill Philip decided to stop supporting the League. He finally recognized Henry's right to the French throne. Without Spanish support, the last League hardliners were quickly defeated. In May 1598, the two kings signed the Peace of Vervins. This ended the last of the religious civil wars and Spain's involvement in them.

Ireland's Role in the War

In 1594, the Nine Years' War began in Ireland. Irish lords Hugh O'Neill and Red Hugh O'Donnell rebelled against English rule. Spain gave them some support, just as England supported the Dutch rebellion. English forces were trying to control the rebels in Ireland. This was very costly in terms of men, suffering, and money.

Meanwhile, the Spanish tried two more armadas, in 1596 and 1597. The first was destroyed in a storm off northern Spain. The second was stopped by bad weather as it neared the English coast. Philip II died in 1598, and his son, Philip III, continued the war but with less enthusiasm.

At the end of 1601, the Spanish sent a final armada north. This was a smaller mission to land troops in Ireland to help the rebels. Only half the fleet arrived because a storm scattered it. The ships that did arrive landed far from the Irish rebel forces. The Spanish entered the town of Kinsale with 3,000 troops. The English immediately surrounded them. Later, their Irish allies arrived to surround the English. But poor communication with the rebels led to an English victory at the Battle of Kinsale. The surrounded Spanish accepted the surrender terms and went home. The Irish rebels continued fighting, but surrendered in 1603, just after Elizabeth died.

The new king of England, James I, was the Protestant son of the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots. Her execution had been a direct cause of the war. James saw himself as a peacemaker in Europe. His main goal was to unite Christian countries. So, when James became king of England, his first task was to make peace with Philip III.

How the War Ended

With the war in France over, Philip III also wanted peace with England. By 1598, the war had become long and expensive for Spain. England and the Dutch Republic were also tired of fighting. Both sides felt they needed peace. However, in peace talks in 1600, England and the Dutch strongly rejected Spanish demands. Still, diplomatic discussions continued between the Archduke of Austria and his wife Infanta Isabella (Philip's sister). They had different ideas than Philip. Philip wanted to keep Spain's power, while the Archduke and Isabella wanted peace and good relations.

Soon after the victory in Ireland the next year, the English navy under Richard Leveson began a blockade of Spain. This was the first of its kind. Off Portugal, they sailed into Sesimbra bay. A fleet of eight Spanish galleys under Federico Spinola (Ambrogio's brother) and Álvaro de Bazán were there. Spinola had already set up his base in Sluis in Flanders. He was gathering more ships to possibly attack England. In June 1602, Leveson defeated the Spanish. Two galleys were sunk, and a rich Portuguese ship was captured. Months later, in the English Channel, Spinola's fleet gathered more galleys and sailed through the English Channel again. But they were defeated again by an Anglo-Dutch naval group off the Dover straits. Spinola's remaining galleys finally reached Sluis. This battle forced the Spanish to stop further naval operations against England for the rest of the war. After Elizabeth I died, Spain's main goal was no longer to invade England, but to take Ostend.

Peace Treaty and What Happened Next

The treaty brought things back to how they were before the war started. The terms were good for both Spain and England. For Spain, the treaty confirmed its position as a leading world power. Spain's improved convoy system had helped it protect its treasure fleets and keep its colonies in the New World. English support for the Dutch rebellion against the Spanish king, which caused the war, stopped. Spain could then focus its efforts on the Dutch, hoping to defeat them. However, the treaty did not promise a complete abandonment of the Dutch cause. The English-held cautionary towns in Holland were not given up, despite Spanish demands. The sieges of Ostend and Sluis were allowed to continue until those battles ended. The Dutch actually won by 1607. The Spanish did not deliver the knockout blow they hoped for. The Twelve Years' Truce effectively recognized the Dutch Republic's independence.

For England, the treaty was a diplomatic success and an economic necessity. At the same time, many English people did not like the treaty. They thought it was a humiliating peace. Many felt that James had abandoned England's ally, the Netherlands, to please Spain. This hurt James's popularity. However, the treaty made sure the Protestant Reformation in England was protected. James and his ministers refused Spain's demand for Catholics to be tolerated in England. After the defeat at Kinsale in 1602, the Treaty of Mellifont was signed the next year between James I and the Irish rebels. In the later London treaty, Spain promised not to support the rebels.

The treaty was well received in Spain. Big public celebrations were held in Valladolid, the Spanish capital. The treaty was officially approved there in June 1605. A large English group of ambassadors, led by Lord Admiral Charles Howard, was present. Still, some Catholic clergy criticized Philip III for signing a treaty with a "heretical power."

The treaty allowed merchants and warships of both nations to use each other's ports. English trade with the Spanish Netherlands (especially Antwerp) and the Iberian Peninsula restarted. Spanish warships and privateers could use English ports as naval bases. They could attack Dutch shipping or transport troops to Flanders.

The war had slowed down England's efforts to build colonies. But the English who invested in privateering expeditions during the war made huge profits. This put them in a good position to pay for new ventures. As a result, the London Company was able to set up a settlement in Virginia in 1607. The creation of the East India Company in 1600 was important for England's growth as a colonial power. A trading post was set up at Banten, Java, in 1603. The Company successfully broke the Spanish and Portuguese trade monopoly and made profits.

While the illegal trade with Spanish colonies ended, there was a disagreement. England wanted the right to trade in the East and West Indies, which Spain strongly opposed. In the end, the treaty did not mention this issue at all.

For Spain, there was hope that England would eventually allow Catholics more freedom. But the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 destroyed any chance of this. The strong anti-Catholic reaction after the plot's discovery calmed Protestant fears. They had worried that peace with Spain would mean an invasion by Catholic priests and supporters. The laws against Catholics were strictly enforced by Parliament.

England and Spain remained at peace until 1625.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra anglo-española (1585-1604) para niños

In Spanish: Guerra anglo-española (1585-1604) para niños

- Anglo-Spanish War (1625–30)

- European wars of religion

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |