Stephen, King of England facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Stephen |

|

|---|---|

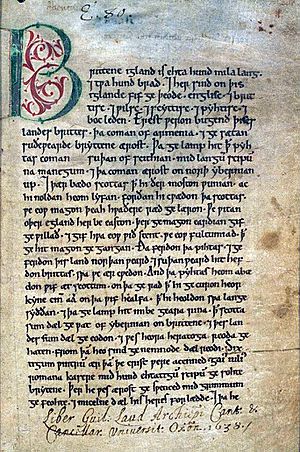

Portrait by Matthew Paris

|

|

| King of England (more...) | |

| Reign | 22 December 1135 – 25 October 1154 |

| Coronation | 22 December 1135 |

| Predecessor | Henry I |

| Successor | Henry II |

| Duke of Normandy | |

| Reign | 1135–1144 |

| Predecessor | Henry I |

| Successor | Geoffrey Plantagenet |

| Born | 1092 or 1096 Blois, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 25 October 1154 (aged c. 57–62) Dover, Kent, Kingdom of England |

| Burial | Faversham Abbey, Kent, England |

| Spouse | |

| Issue more... |

|

| House | Blois |

| Father | Stephen, Count of Blois |

| Mother | Adela of Normandy |

Stephen (born 1092 or 1096 – died 25 October 1154), also known as Stephen of Blois, was the King of England from 1135 until his death in 1154. He was also the Count of Boulogne and Duke of Normandy for some years. His time as king was marked by a long civil war called the Anarchy. He fought against his cousin and rival, the Empress Matilda. Her son, Henry II, became king after Stephen. Henry was the first of the Angevin kings of England.

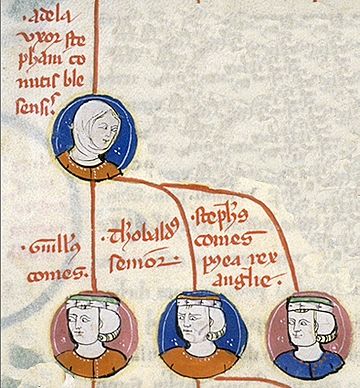

Stephen was born in Blois, France. He was the fourth son of Stephen-Henry, Count of Blois, and Adela, who was the daughter of William the Conqueror. Stephen's father died when he was young, so his mother raised him. He grew up in the court of his uncle, Henry I of England. Stephen became important and received a lot of land. He married Matilda of Boulogne. She brought him even more land in Kent and Boulogne. This made them one of the richest couples in England.

In 1120, Stephen nearly drowned in the White Ship disaster. Henry I's son, William Adelin, died in this accident. This meant the English throne was open for someone else to claim. When Henry I died in 1135, Stephen quickly went to England. With help from his brother, Henry, Bishop of Winchester, he took the throne. Stephen argued that keeping peace was more important than his earlier promise to support Matilda.

The first years of Stephen's rule went well. But there were attacks on his lands in England and Normandy. These came from David I of Scotland, Welsh rebels, and Matilda's husband, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. In 1138, Matilda's half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, rebelled. This threatened civil war. Stephen worked with his advisor, Waleran de Beaumont, to defend his rule. He even arrested some powerful bishops.

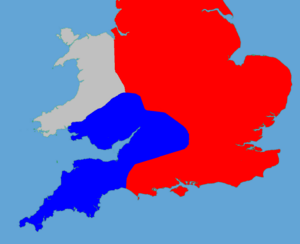

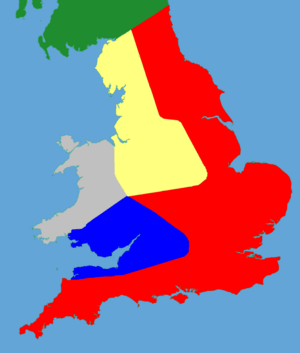

When Matilda and Robert invaded in 1139, Stephen could not stop the revolt quickly. It spread in the south-west of England. Stephen was captured at the Battle of Lincoln in 1141. Many of his followers left him, and he lost control of Normandy. He was freed only after his wife and William of Ypres captured Robert. But the war continued for many years, with neither side winning easily.

Stephen wanted his son, Eustace, to become king after him. He tried to get the church to crown Eustace. But Pope Eugene III refused. This led to arguments between Stephen and his church leaders. In 1153, Matilda's son, Henry, invaded England. He gathered powerful barons to support his claim. The two armies met at Wallingford. But the barons did not want to fight another big battle. Stephen started to think about a peace deal. Eustace's sudden death helped this process. Later that year, Stephen and Henry agreed to the Treaty of Winchester. In this treaty, Stephen named Henry as his heir. This meant Stephen's second son, William, would not become king. Stephen died the next year. Historians still discuss why this long civil war happened.

Contents

Early Life (1097–1135)

Childhood and Family

Stephen was born in Blois, France, either in 1092 or 1096. His father was Stephen-Henry, a powerful French nobleman and a crusader. His father was not a big part of Stephen's early life.

During the First Crusade, Stephen-Henry gained a reputation for being afraid. He went back to the Middle East in 1101 to try and fix his reputation. He was killed there in the Battle of Ramlah. Stephen's mother, Adela, was the daughter of William the Conqueror. She was known for being religious, rich, and good at politics. She had a strong influence on Stephen when he was young.

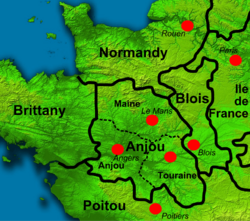

France in the 12th century was a collection of smaller areas called counties. The King of France had little control over them. The King's power came from his control of the rich area of Île-de-France. This was just east of Stephen's home county of Blois. To the west were the counties of Maine, Anjou, and Touraine. North of Blois was the Duchy of Normandy. William the Conqueror had used Normandy to conquer England in 1066. William's children were still fighting over these lands.

The rulers in this region spoke a similar language. They followed the same religion and were often related. But they also competed a lot and often fought over land and castles.

Stephen had at least four brothers and one sister. His oldest brother, William, would normally have ruled Blois. But William had learning difficulties. So, Adela gave the counties to her second son, Theobald II. Stephen's other older brother, Odo, died young.

Stephen's younger brother, Henry, was born about four years after him. The brothers were very close. Adela wanted Stephen to become a knight. She wanted Henry to join the church. This way, their career interests would not clash. Stephen was raised in his mother's home, which was unusual. He learned Latin and riding. He also learned about history and Biblical stories from his tutor.

Stephen and Henry I

Stephen's early life was greatly shaped by his uncle, Henry I of England. Henry became king after his older brother, William Rufus, died. In 1106, Henry took control of the Duchy of Normandy. He defeated his oldest brother, Robert Curthose, at the Battle of Tinchebray. Henry then fought with Louis VI of France. Louis wanted Robert's son, William Clito, to be Duke of Normandy.

Henry made alliances with French counties against Louis. This led to a long regional conflict. Adela and Theobald joined Henry. Stephen's mother decided to send him to Henry's court. Stephen was probably with Henry during a military campaign in 1112. The King made him a knight then. Stephen first visited England around 1113 or 1115. He was likely part of Henry's court.

Henry supported Stephen a lot. He probably chose Stephen because he was family and an ally. But Stephen was not rich or powerful enough to threaten the King or his son, William Adelin. As a third son, Stephen needed a powerful supporter to succeed.

With Henry's help, Stephen quickly gained land and wealth. After the Battle of Tinchebray in 1106, Henry took the County of Mortain and the Honour of Eye. In 1113, Stephen received these titles. He also got the Honour of Lancaster. Henry also gave Stephen lands in Alençon in Normandy. But the local Normans rebelled. Stephen and Theobald were defeated in the Battle of Alençon. They did not get these lands back.

Finally, in 1125, the King arranged for Stephen to marry Matilda. She was the only child of Eustace III, Count of Boulogne. Matilda owned the important port of Boulogne and large estates in England. In 1127, William Clito might have become the Count of Flanders. Henry sent Stephen to stop this. After William Clito became Count, he attacked Stephen's lands in Boulogne. They made a truce, and William died the next year.

The White Ship and Succession

In 1120, English politics changed greatly. Three hundred people were on the White Ship going from Normandy to England. This included William Adelin, the heir to the throne, and many other important nobles. Stephen had planned to be on this ship. But he changed his mind at the last minute. He got off to wait for another ship, perhaps because it was too crowded or he felt unwell. The ship sank, and almost everyone died, including William Adelin.

With William Adelin gone, who would inherit the English throne was unclear. Rules for who became king were not set in stone in Europe then. In some parts of France, the oldest son inherited everything. It was also common for the King of France to crown his successor while still alive. This made the next king clear. But this was not the case in England. In England and Normandy, land was often divided. The oldest son got the most valuable lands. Younger sons got smaller or newer areas. The problem was made worse by recent unstable successions. William the Conqueror had taken England by force. William Rufus and Robert Curthose had fought over their inheritance. Henry had also taken Normandy by force. There had been no peaceful change of power.

Henry I had only one other child, the future Empress Matilda. But as a woman, she was at a big disadvantage. Henry took a second wife, Adeliza of Louvain, but it seemed unlikely he would have another son. So, he looked to Matilda as his heir. Matilda was called Holy Roman Empress because she had married Emperor Henry V. He died in 1125. In 1128, she married Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. His lands bordered Normandy. Geoffrey was not popular with the Anglo-Norman nobles. He was an Angevin ruler, a traditional enemy of the Normans. At the same time, Henry's policies caused tension. He was raising a lot of money for his wars. But the King's strong personality kept conflict in check.

Henry tried to get political support for Matilda in England and Normandy. He made his court swear oaths in 1127, 1128, and 1131. They had to promise to accept Matilda as his successor. Stephen was among those who took this oath in 1127. But relations between Henry, Matilda, and Geoffrey grew tense. Matilda and Geoffrey felt they lacked real support in England. In 1135, they asked Henry to give Matilda the royal castles in Normandy. They wanted the Norman nobles to swear loyalty to her right away. This would give them more power after Henry died. Henry angrily refused. He worried Geoffrey would try to take power too soon. A new rebellion started in southern Normandy. Geoffrey and Matilda joined the rebels. During this fight, Henry suddenly became ill and died near Lyons-la-Forêt.

Becoming King (1135)

By 1135, Stephen was well-known in Anglo-Norman society. He was very rich, polite, and liked by others. He was also seen as someone who could act firmly. Writers of the time said he was modest and easy-going. He would laugh and eat with his men and servants. He was also very religious. He followed church rules and gave generously to the church. Stephen had a personal confessor from the Archbishop of Canterbury. Stephen also encouraged the new Cistercian monks to build abbeys on his lands. This gained him more allies in the church.

However, rumors about his father's actions during the First Crusade continued. Stephen's desire to avoid a similar reputation might have made him take some risky military actions. His wife, Matilda, managed their large English estates. This made them the second-richest family in the country, after the King and Queen. William of Ypres, a Flemish nobleman, joined Stephen's household in 1133.

Stephen's younger brother, Henry, also gained power under Henry I. Henry of Blois became a monk. He followed Stephen to England. The King made him Abbot of Glastonbury, the richest abbey in England. Then, the King made him Bishop of Winchester, one of the richest bishoprics. He kept Glastonbury too. The money from both made Henry of Winchester the second-richest man in England. Henry of Winchester wanted to stop kings from controlling the church. Norman kings had traditionally held much power over the church. But from the 1040s, popes wanted the church to be more independent.

When news of Henry I's death spread, many possible heirs were not in a good position. Geoffrey and Matilda were in Anjou. They were supporting rebels against the royal army. Many barons had sworn to stay in Normandy until the King was buried. This stopped them from returning to England. Stephen's brother Theobald was even further south in Blois. But Stephen was in Boulogne. When he heard the news, he left for England with his soldiers. Some reports say that the ports of Dover and Canterbury refused him entry at first. But Stephen probably reached his estate near London by December 8. Over the next week, he began to take power in England.

The people of London traditionally claimed the right to choose the King. They declared Stephen the new monarch. They believed he would give the city new rights. Henry of Blois helped Stephen get the church's support. Stephen went to Winchester. There, Roger, Bishop of Salisbury and Lord Chancellor, gave the royal treasury to Stephen. On December 15, Henry made a deal. Stephen would give the church many freedoms. In return, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Papal Legate would support him. Stephen had sworn an oath to support Empress Matilda. But Henry argued that the late king was wrong to make that oath.

Henry said the oath was only to keep the kingdom stable. Given the chaos that might happen, Stephen was right to ignore it. Henry also convinced Hugh Bigod, the late king's steward, to swear that the King had changed his mind. Bigod claimed Henry I had named Stephen as his successor on his deathbed. Stephen was crowned a week later at Westminster Abbey on December 22.

Meanwhile, Norman nobles met at Le Neubourg. They discussed making Theobald king. They heard Stephen was gaining support in England. The Normans argued that Theobald, as the older grandson of William the Conqueror, had the best claim. He was certainly better than Matilda.

Theobald met with Norman barons and Robert of Gloucester on December 21. Their talks were stopped by news that Stephen's coronation was the next day. Theobald then agreed to be king. But his support quickly disappeared. The barons did not want to divide England and Normandy by opposing Stephen. Stephen later paid Theobald money. In return, Theobald stayed in Blois and supported his brother.

Early Reign (1136–1139)

First Years (1136–1137)

Stephen's new kingdom was shaped by the Norman conquest of England in 1066. Then came the Norman expansion into south Wales. A few powerful barons controlled both England and Normandy. Lesser barons usually held local lands. It was still unclear if land and titles should be passed down by family right or given by the King. Tensions over this had grown under Henry I. Lands in Normandy, passed down by family, were often more important to barons. Henry I had made the royal government stronger. He often brought in "new men" for key jobs instead of using old nobles. He collected more money and spent less. This led to a large treasury but also more political tension.

Stephen had to act in northern England right after his coronation. David I of Scotland invaded the north when he heard Henry I had died. He took Carlisle, Newcastle, and other strongholds. Northern England was disputed. Scottish kings claimed Cumberland. David also claimed Northumbria through his marriage. Stephen quickly marched north with an army. He met David at Durham. They made a deal. David would return most of the land he had taken, except Carlisle. In return, Stephen confirmed David's son Henry's English lands, including the Earldom of Huntingdon.

Back south, Stephen held his first royal court at Easter 1136. Many Anglo-Norman barons and church officials gathered at Westminster. Stephen issued a new royal charter. He confirmed his promises to the church. He promised to change Henry I's policies on royal forests. He also promised to fix abuses in the royal legal system. He presented himself as Henry's natural successor. He confirmed the existing seven earldoms. The Easter court was grand and costly. Stephen spent a lot on the event, clothes, and gifts. He gave land and favors to those present. He also gave land and rights to many church groups. His rule still needed the Pope's approval. Henry of Blois made sure letters of support were sent from Theobald and King Louis VI of France. Louis saw Stephen as a good balance to Angevin power. Pope Innocent II confirmed Stephen as king later that year. Stephen's advisors spread copies around England to show his right to rule.

Problems continued across Stephen's kingdom. After Welsh victories in January and April 1136, south Wales rebelled. The rebellion started in east Glamorgan and spread quickly in 1137. Owain Gwynedd and Gruffydd ap Rhys captured much land, including Carmarthen Castle. Stephen sent Richard's brother Baldwin and Robert Fitz Harold to calm the region. Neither mission worked well. By late 1137, Stephen seemed to have given up on stopping the rebellion. Historian David Crouch says Stephen "bowed out of Wales" to focus on other issues. Meanwhile, Stephen stopped two revolts in the south-west. These were led by Baldwin de Redvers and Robert of Bampton. Baldwin was freed and went to Normandy. He became a strong critic of the King.

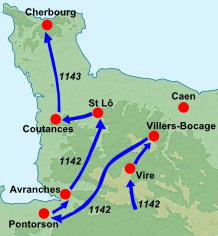

Normandy's safety was also a worry. Geoffrey of Anjou invaded in early 1136. After a short truce, he invaded again later that year. He raided and burned estates instead of holding land. Stephen could not go to Normandy himself. So, Waleran de Beaumont, Stephen's lieutenant in Normandy, and Theobald led the defense. Stephen only returned to Normandy in 1137. He met with Louis VI and Theobald. They agreed to an informal alliance. This was likely arranged by Henry. It was to counter the growing Angevin power. As part of this deal, Louis recognized Stephen's son Eustace as Duke of Normandy. In return, Eustace swore loyalty to the French King. Stephen was less successful in getting back the Argentan area. Geoffrey had taken it in late 1135. Stephen formed an army to retake it. But his Flemish soldiers and Norman barons fought each other. The Norman forces then left Stephen. This forced the King to give up his campaign. He agreed to another truce with Geoffrey. He promised to pay him 2,000 marks a year for peace.

In the years after becoming king, Stephen's relationship with the church became more complex. The royal charter of 1136 promised to review land ownership. It said lands taken by the crown from the church since 1087 would be returned. But nobles now owned these estates. Henry of Blois, as Abbot of Glastonbury, claimed large lands in Devon. This caused local unrest. In 1136, Archbishop of Canterbury William de Corbeil died. Stephen took his personal wealth. This upset some senior clergy. Henry wanted to become Archbishop. But Stephen supported Theobald of Bec, who was appointed. The Pope named Henry papal legate. This might have been a comfort prize.

Stephen's first few years as king can be seen in different ways. He made the Scottish border stable. He stopped Geoffrey's attacks on Normandy. He was at peace with Louis VI. He had good relations with the church. And he had wide support from his barons. But there were big problems. David and Prince Henry now controlled northern England. Stephen had given up on Wales. The fighting in Normandy had made the duchy unstable. More barons felt Stephen had not given them enough land or titles. Stephen was also running out of money. Henry I's large treasury was empty by 1138. This was due to Stephen's lavish court and the cost of his mercenary armies.

Defending the Kingdom (1138–1139)

Stephen was attacked from several sides in 1138. First, Robert, Earl of Gloucester, rebelled. This started the civil war in England. Robert was Henry I's illegitimate son and Empress Matilda's half-brother. He was one of the most powerful Anglo-Norman barons. He controlled lands in Normandy. Robert had tried to get Theobald to take the throne in 1135. He did not attend Stephen's first court in 1136. It took several requests to get him to attend court in Oxford later that year. In 1138, Robert stopped supporting Stephen. He declared his support for Matilda. This caused a big rebellion in Kent and south-west England. Robert himself stayed in Normandy. In France, Geoffrey of Anjou used the situation to invade Normandy again. David of Scotland also invaded northern England again. He said he was supporting his niece Empress Matilda. He pushed south into Yorkshire.

Warfare in Stephen's time involved trying to capture enemy castles. This allowed commanders to control enemy land and slowly win. Armies had mounted, armored knights. They were supported by infantry and crossbowmen. These forces were either feudal levies, local nobles serving for a short time, or mercenaries. Mercenaries were expensive but more flexible and skilled. These armies were not good at attacking castles. Old motte-and-bailey castles or new stone keeps were hard to take. Siege engines were not as strong as later ones. So, commanders preferred long sieges to starve defenders. Or they would dig tunnels to weaken walls. Big battles were risky and usually avoided. The cost of war had risen a lot. Having enough money was very important for successful campaigns.

Stephen was a good military leader. He was skilled in personal combat and siege warfare. He could move his army quickly over long distances. To respond to the revolts, he quickly launched several campaigns. He focused mainly on England. His wife Matilda went to Kent with ships and resources from Boulogne. Her job was to retake the port of Dover, which Robert controlled. Some of Stephen's knights went north to fight the Scots. David's forces were defeated at the Battle of the Standard in August. This was done by the forces of Thurstan, the Archbishop of York. But David still held most of the north. Stephen himself went west to regain control of Gloucestershire. He went north into the Welsh Marches, taking Hereford and Shrewsbury. Then he went south to Bath. The town of Bristol was too strong for him. Stephen just raided the area around it. The rebels seemed to expect Robert to help that year. But he stayed in Normandy, trying to convince Empress Matilda to invade England. Dover finally surrendered to the queen's forces later that year.

Stephen's military campaign in England went well. Historian David Crouch called it "a military achievement of the first rank." The King used his military advantage to make peace with Scotland. Stephen's wife Matilda negotiated another deal with David. It was called the Treaty of Durham. Northumbria and Cumbria would be given to David and his son Henry. In return, they would be loyal and keep the border peaceful. But the powerful Ranulf I, Earl of Chester was very unhappy. He felt he had rights to Carlisle and Cumberland. Still, Stephen could now focus on the expected invasion by Robert and Matilda.

Road to Civil War (1139)

Stephen prepared for the Angevin invasion by creating new earldoms. Under Henry I, there were only a few earldoms, and they were mostly symbolic. Stephen created many more. He filled them with men he thought were loyal and good military leaders. In vulnerable areas, he gave them new lands and more power. He wanted to ensure the loyalty of his key supporters. He also wanted to improve his defenses. Stephen was greatly influenced by his main advisor, Waleran de Beaumont. Waleran and his twin brother, Robert of Leicester, and their family received most of these new earldoms. From 1138, Stephen gave them the earldoms of Worcester, Leicester, Hereford, Warwick, and Pembroke. These, along with Prince Henry's lands, created a large area. This area acted as a buffer zone between the troubled south-west, Chester, and the rest of the kingdom. The Beaumonts' power grew so much that David Crouch suggests it became "dangerous to be anything other than a friend of Waleran" at Stephen's court.

Stephen took steps to remove some bishops he saw as a threat. Henry I's government was led by Roger, Bishop of Salisbury. His nephews, Bishops Alexander of Lincoln and Nigel of Ely, and his son, Lord Chancellor Roger le Poer, supported him. These bishops owned a lot of land and had their own armies. Stephen suspected they might switch to Empress Matilda. Bishop Roger and his family were also enemies of Waleran. Waleran did not like their control of the royal government. In June 1139, Stephen held his court in Oxford. A fight broke out between Alan of Brittany and Roger's men. Stephen probably caused this incident on purpose. Stephen demanded that Roger and the other bishops give up all their castles. He arrested the bishops, except Nigel, who hid in Devizes Castle. Nigel only gave up after Stephen attacked the castle and threatened to kill Roger le Poer. The remaining castles were then given to the King.

Stephen's brother Henry was worried by this. First, Stephen had promised in 1135 to respect the church's freedoms. Second, Henry himself had recently built six castles. He did not want to be treated the same way. As the papal legate, he called the King to appear before a church council. Stephen had to answer for the arrests and taking of property. Henry said the church had the right to judge all charges against clergy. Stephen sent Aubrey de Vere II to speak for him. Aubrey argued that Roger of Salisbury was arrested as a baron, not a bishop. He said Roger was planning to switch to Empress Matilda. Hugh of Amiens, Archbishop of Rouen, supported the King. He challenged the bishops to show how church law allowed them to build castles. Aubrey threatened that Stephen would complain to the pope. He said Stephen was being bothered by the English church. The council let the matter go after an appeal to Rome failed. This event removed any military threat from the bishops. But it might have hurt Stephen's relationship with the senior clergy, especially his brother Henry.

Civil War (1139–1154)

First Phase of the War (1139–1140)

The Angevin invasion finally arrived in 1139. Baldwin de Redvers crossed from Normandy to Wareham in August. He tried to capture a port for Empress Matilda's army. But Stephen's forces made him retreat. The next month, Henry I's widow, Adeliza, invited Matilda to land at Arundel. On September 30, Robert of Gloucester and the Empress arrived in England with 140 knights. The Empress stayed at Arundel Castle. Robert marched north-west to Wallingford and Bristol. He hoped to get support and join Miles of Gloucester. Miles was a skilled military leader who stopped supporting the King. Stephen quickly moved south. He attacked Arundel and trapped Matilda inside.

Stephen then agreed to a truce proposed by his brother Henry. The full details are not known. But Stephen released Matilda from the siege. He allowed her and her knights to be escorted to the south-west. There, they rejoined Robert. Why Stephen released his rival is still unclear. Some writers at the time said Henry argued it was best for Stephen. He should focus on attacking Robert instead. Stephen might have seen Robert as his main enemy. He also faced a problem at Arundel. The castle was very strong. He might have worried about tying up his army in the south. Meanwhile, Robert was free in the west. Another idea is that Stephen released Matilda out of chivalry. He was known for being generous and polite. Women were not usually targeted in Anglo-Norman warfare.

After releasing the Empress, Stephen focused on calming south-west England. Few new people had joined the Empress. But his enemies now controlled a solid area. It stretched from Gloucester and Bristol into Devon and Cornwall. It went west into Wales and east to Oxford and Wallingford. This threatened London. Stephen started by attacking Wallingford Castle. It was held by Matilda's childhood friend, Brien FitzCount. But it was too well defended. Stephen left some forces to block the castle. He continued west into Wiltshire to attack Trowbridge Castle. He took the castles of South Cerney and Malmesbury along the way. Meanwhile, Miles of Gloucester marched east. He attacked Stephen's forces at Wallingford. He threatened to advance on London. Stephen had to stop his western campaign. He returned east to stabilize the situation and protect his capital.

In early 1140, Nigel, Bishop of Ely, rebelled against Stephen. Stephen had taken Nigel's castles the year before. Nigel hoped to seize East Anglia. He set up his base in the Isle of Ely, surrounded by fenland. Stephen reacted quickly. He took an army into the fens. He used boats tied together to make a path. This allowed him to surprise attack the isle. Nigel escaped to Gloucester. But his men and castle were captured. Order was temporarily restored in the east. Robert of Gloucester's men retook some land Stephen had taken in 1139. To negotiate a truce, Henry of Blois held a peace meeting at Bath. Stephen sent his wife. The meeting failed. Henry and the clergy insisted they should set the peace terms. Stephen found this unacceptable.

Ranulf of Chester was still angry about Stephen giving northern England to Prince Henry. Ranulf planned to ambush Henry as he returned to Scotland from Stephen's court. Stephen heard rumors of this plan. He escorted Henry north himself. But this act was the last straw for Ranulf. Ranulf had claimed rights to Lincoln Castle, which Stephen held. Under the guise of a social visit, Ranulf took the castle by surprise. Stephen marched north to Lincoln. He agreed to a truce with Ranulf. This was probably to keep him from joining the Empress. Ranulf would be allowed to keep the castle. Stephen returned to London. But he heard that Ranulf, his brother, and family were relaxing in Lincoln Castle with few guards. It was a good target for a surprise attack. Stephen broke his deal. He gathered his army and rushed north. But he was not quite fast enough. Ranulf escaped Lincoln and declared support for the Empress. Stephen had to lay siege to the castle.

Second Phase of the War (1141–1142)

While Stephen's army besieged Lincoln Castle in early 1141, Robert and Ranulf advanced. They had a larger force. When Stephen heard this, he held a meeting. He had to decide whether to fight or retreat for more soldiers. Stephen chose to fight. This led to the Battle of Lincoln on February 2, 1141. The King commanded the center of his army. Alan of Brittany was on his right, and William of Aumale on his left. Robert and Ranulf's forces had more cavalry. Stephen made many of his knights get off their horses. They formed a strong infantry block. He joined them, fighting on foot. Stephen was not a great speaker. He let Baldwin of Clare give the pre-battle speech. After an early success, where William's forces destroyed the Welsh infantry, the battle went badly for Stephen. Robert and Ranulf's cavalry surrounded Stephen's center. The King found himself surrounded. Many of his supporters, including Waleran de Beaumont and William of Ypres, fled. But Stephen kept fighting. He defended himself first with his sword, then with a borrowed battle axe. Finally, Robert's men overwhelmed him. He was taken away as a prisoner.

Robert took Stephen to Gloucester. There, the King met Empress Matilda. Then he was moved to Bristol Castle, a place for important prisoners. At first, he was held in good conditions. But later, his security was tightened, and he was kept in chains. The Empress began to prepare to be crowned queen. This needed the church's agreement and a coronation at Westminster. Bishop Henry called a council at Winchester before Easter. He was the papal legate. He wanted to hear the clergy's opinion. He had made a private deal with Matilda. He would get the church's support if she gave him control over church matters in England. Henry gave the royal treasury, which was almost empty, to the Empress. He also excommunicated many of Stephen's supporters who refused to switch sides. Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury did not want to declare Matilda queen so quickly. A group of clergy and nobles, led by Theobald, went to see Stephen in Bristol. They asked about their moral problem: should they break their oaths to the King? Stephen agreed that, given the situation, he would release his subjects from their oath to him. The clergy met again in Winchester after Easter. They declared the Empress "Lady of England and Normandy." This was a step before her coronation. But when Matilda went to London for her coronation in June, the citizens rebelled. They supported Stephen. This forced her to flee to Oxford, uncrowned.

When news of Stephen's capture reached him, Geoffrey of Anjou invaded Normandy again. Waleran of Beaumont was still fighting in England. Geoffrey took all the duchy south of the river Seine and east of the river Risle. Stephen's brother Theobald did not help this time. He seemed busy with his own problems with France. The new French king, Louis VII, had rejected his father's alliance. He improved relations with Anjou and was tougher on Theobald. This would lead to war the next year. Geoffrey's success in Normandy and Stephen's weakness in England affected many Anglo-Norman barons. They feared losing their lands in England to Robert and the Empress. They also feared losing their lands in Normandy to Geoffrey. Many started to leave Stephen's side. His friend and advisor Waleran was one of them. He switched sides in mid-1141. He went to Normandy to protect his family lands by joining the Angevins. He also brought Worcestershire to the Empress's side. Waleran's twin brother, Robert of Leicester, stopped fighting in the conflict. Other supporters of the Empress got their old strongholds back. Bishop Nigel of Ely was one. Others received new earldoms in western England. The royal control over minting coins broke down. Local barons and bishops started making their own coins.

Stephen's wife Matilda was crucial in keeping the King's cause alive. Queen Matilda gathered Stephen's remaining leaders and the royal family in the south-east. She went into London when the people rejected the Empress. Stephen's long-time commander William of Ypres stayed with the Queen in London. William Martel, the royal steward, led operations from Sherborne in Dorset. Faramus of Boulogne managed the royal household. The Queen seemed to gain real sympathy and support from Stephen's loyal followers. Henry's alliance with the Empress did not last long. They argued over political favors and church policy. The bishop met the Queen at Guildford and switched his support to her.

The King was finally released after the Angevin defeat at the rout of Winchester. Robert of Gloucester and the Empress attacked Henry in Winchester in July. Queen Matilda and William of Ypres then surrounded the Angevin forces. They had new troops from London. In the battle, the Empress's forces were defeated. Robert of Gloucester was taken prisoner. More talks tried to make a general peace. But the Queen would not compromise with the Empress. Robert refused to switch sides to Stephen. Instead, in November, they simply exchanged Robert and the King. Stephen released Robert on November 1, 1141. Stephen began to regain his power. Henry held another church council. This time, it confirmed Stephen's right to rule. Stephen and Matilda had another coronation at Christmas 1141.

At the start of 1142, Stephen became ill. By Easter, rumors spread that he had died. This illness might have been from his imprisonment. But he recovered. He traveled north to gather new forces. He successfully convinced Ranulf of Chester to switch sides again. Stephen then spent the summer attacking new Angevin castles. These included Cirencester, Bampton, and Wareham. In September, he saw a chance to capture Empress Matilda herself in Oxford. Oxford was a safe town. It was protected by walls and the river Isis. But Stephen led a sudden attack across the river. He led the charge, swimming part of the way. Once on the other side, the King and his men stormed the town. They trapped the Empress in the castle. Oxford Castle was a strong fortress. Stephen had to settle for a long siege. He knew Matilda was surrounded. Just before Christmas, the Empress left the castle without being seen. She crossed the icy river on foot and escaped to Wallingford. The castle guards surrendered soon after. But Stephen had missed a chance to capture his main opponent.

Stalemate (1143–1146)

The war in England reached a standstill in the mid-1140s. Meanwhile, Geoffrey of Anjou took firm control of Normandy. 1143 started badly for Stephen. Robert of Gloucester besieged him at Wilton Castle, a meeting point for royal forces. Stephen tried to break out and escape. This led to the Battle of Wilton. Again, the Angevin cavalry was too strong. For a moment, it looked like Stephen might be captured again. But this time, William Martel, Stephen's steward, fought hard at the back. This allowed Stephen to escape. Stephen valued William's loyalty. He agreed to trade Sherborne Castle for William's safe release. This was one of the few times Stephen gave up a castle to free one of his men.

In late 1143, Stephen faced a new threat in the east. Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex, rebelled against him in East Anglia. The King had disliked the Earl for years. He started the conflict by calling Geoffrey to court. There, the King arrested him. He threatened to kill Geoffrey unless the Earl gave up his castles. These included the Tower of London, Saffron Walden, and Pleshey. These were important forts near London. Geoffrey gave in. But once free, he went north-east into the Fens to the Isle of Ely. From there, he began a military campaign against Cambridge. He planned to go south towards London. With all his other problems, and Hugh Bigod, 1st Earl of Norfolk, openly rebelling in Norfolk, Stephen lacked the resources to chase Geoffrey in the Fens. He built a line of castles between Ely and London, including Burwell Castle.

For a time, the situation got worse. Ranulf of Chester rebelled again in summer 1144. He split Stephen's Honour of Lancaster between himself and Prince Henry. In the west, Robert of Gloucester and his followers kept raiding royal lands. Wallingford Castle remained a strong Angevin base, too close to London. Meanwhile, Geoffrey of Anjou finished securing southern Normandy. In January 1144, he entered Rouen, the capital of the duchy. Louis VII recognized him as Duke of Normandy soon after. By this point, Stephen relied more on his close royal household, like William of Ypres. He lacked support from major barons who could provide many soldiers. After 1141, Stephen used his network of earls less.

After 1143, the war continued, but slightly better for Stephen. Miles of Gloucester, a skilled Angevin commander, died while hunting. This eased some pressure in the west. Geoffrey de Mandeville's rebellion lasted until September 1144. He died during an attack on Burwell. The war in the west improved in 1145. The King recaptured Faringdon Castle in Oxfordshire. In the north, Stephen made a new deal with Ranulf of Chester. But then in 1146, he used the same trick he played on Geoffrey de Mandeville. He invited Ranulf to court. Then he arrested him. He threatened to kill him unless he gave up castles like Lincoln and Coventry. Like Geoffrey, Ranulf rebelled as soon as he was freed. But it was a stalemate. Stephen had few soldiers in the north for a new campaign. Ranulf lacked castles to attack Stephen. By this point, Stephen's practice of arresting barons at court made him distrusted.

Final Phases of the War (1147–1152)

England had suffered greatly from the war by 1147. Later historians called this period "the Anarchy". The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle said there was "nothing but disturbance and wickedness and robbery." In many areas, like Wiltshire, Berkshire, the Thames Valley, and East Anglia, fighting caused serious damage. Many "adulterine" or unauthorized castles were built by local lords. One writer complained that 1,115 such castles were built, though this was likely too high. The royal coinage system broke down. Stephen, the Empress, and local lords all made their own coins. Royal forest law collapsed in many parts. But some areas were barely touched. Stephen's lands in the south-east and the Angevin areas around Gloucester and Bristol were mostly fine. David I ruled his northern English lands well. Stephen's income from his lands fell sharply, especially after 1141. Royal control over minting new coins remained limited outside the south-east and East Anglia. Stephen was often in the south-east, so Westminster, not Winchester, became the center of royal government.

The nature of the conflict in England slowly changed. Historian Frank Barlow suggests that by the late 1140s, "the civil war was over," except for occasional fights. In 1147, Robert of Gloucester died peacefully. The next year, Empress Matilda left south-west England for Normandy. Both events helped slow down the war. The Second Crusade was announced. Many Angevin supporters, including Waleran of Beaumont, joined it. They left the region for several years. Many barons made their own peace deals. They wanted to secure their lands and war gains. Geoffrey and Matilda's son, the future King Henry II of England, led a small mercenary invasion of England in 1147. But the expedition failed. Henry lacked money to pay his men. Surprisingly, Stephen himself paid their costs. This allowed Henry to return home safely. Stephen's reasons are unclear. Perhaps it was his general politeness to family. Or maybe he was starting to think about ending the war peacefully. He might have seen this as a way to build a relationship with Henry.

The young Henry FitzEmpress returned to England in 1149. This time, he planned to form a northern alliance with Ranulf of Chester. The Angevin plan involved Ranulf giving up his claim to Carlisle, held by the Scots. In return, he would get rights to all of the Honour of Lancaster. Ranulf would swear loyalty to both David and Henry FitzEmpress, with Henry being superior. After this peace deal, Henry and Ranulf agreed to attack York. They probably had help from the Scots. Stephen quickly marched north to York. The planned attack fell apart. Henry returned to Normandy, where his father declared him duke.

Though still young, Henry was gaining a reputation as an energetic and capable leader. His status and power grew more when he unexpectedly married Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine in 1152. She was the recently divorced wife of Louis VII. This marriage made Henry the future ruler of a huge amount of land across France.

In the last years of the war, Stephen focused on his family and who would be king next. He wanted to confirm his oldest son, Eustace, as his successor. But writers said Eustace was known for collecting heavy taxes and taking money from people on his lands. Stephen's second son, William, married the very rich heiress Isabel de Warenne, Countess of Surrey. In 1148, Stephen built the Cluniac Faversham Abbey as a burial place for his family. Both Stephen's wife, Matilda, and his brother Theobald died in 1152.

Argument with the Church (1145–1152)

Stephen's relationship with the church got much worse near the end of his rule. The church reform movement, which wanted more independence from royal power, kept growing. New groups like the Cistercians gained more respect among monks. Stephen's argument with the church started in 1140. Archbishop Thurstan of York died. An argument broke out. A group of reformers in York, supported by Bernard of Clairvaux, wanted William of Rievaulx as the new archbishop. Stephen and his brother Henry preferred relatives of the Blois family. The fight between Henry and Bernard became personal. Henry used his power as legate to appoint his nephew William of York in 1141. But when Pope Innocent II died in 1143, Bernard got the appointment rejected by Rome. Bernard then convinced Pope Eugene III to overturn Henry's decision in 1147. He removed William and appointed Henry Murdac as archbishop.

Stephen was very angry. He saw this as the Pope interfering with his royal power. At first, he refused to let Murdac into England. When Theobald, the Archbishop of Canterbury, went to talk to the Pope against Stephen's wishes, the King refused to let him back into England either. He took Theobald's lands. Stephen also cut ties with the Cistercian order. He turned instead to the Cluniacs, which Henry was a member of.

Still, the pressure on Stephen to confirm Eustace as his heir grew. The King gave Eustace the County of Boulogne in 1147. But it was still unclear if Eustace would inherit England. Stephen wanted Eustace crowned while he was still alive, as was the custom in France. But this was not normal in England. Pope Celestine II, during his short time as pope, had forbidden any change to this practice. The only person who could crown Eustace was Archbishop Theobald. He refused to do so without the current pope's agreement. This led to a deadlock. In late 1148, Stephen and Theobald made a temporary deal. Theobald could return to England. Theobald was made a papal legate in 1151, which added to his power. Stephen then tried again to have Eustace crowned at Easter 1152. He gathered his nobles to swear loyalty to Eustace. Then he insisted that Theobald and his bishops crown him king. When Theobald refused again, Stephen and Eustace imprisoned him and the bishops. They refused to release them unless they agreed to crown Eustace. Theobald escaped again into temporary exile in Flanders. Stephen's knights chased him to the coast. This was a low point in Stephen's relationship with the church.

Treaties and Peace (1153–1154)

Henry FitzEmpress returned to England in early 1153 with a small army. He was supported in northern and eastern England by Ranulf of Chester and Hugh Bigod. Henry's forces attacked Stephen's castle at Malmesbury. The King responded by marching west with an army to help it. He tried but failed to force Henry's smaller army to fight a decisive battle along the river Avon. Because of the worsening winter weather, Stephen agreed to a temporary truce. He returned to London. Henry traveled north through the Midlands. There, the powerful Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, announced his support for the Angevin side. Despite only small military successes, Henry and his allies now controlled the south-west, the Midlands, and much of northern England.

Over the summer, Stephen increased the long siege of Wallingford Castle. This was a final attempt to take this major Angevin stronghold. Wallingford seemed about to fall. Henry marched south to relieve the siege. He arrived with a small army and then besieged Stephen's forces. Hearing this, Stephen gathered a large force and marched from Oxford. The two sides faced each other across the River Thames at Wallingford in July. By this point, barons on both sides wanted to avoid an open battle. So, instead of a battle, church members arranged a truce. This annoyed both Stephen and Henry.

After Wallingford, Stephen and Henry talked privately about ending the war. Stephen's son Eustace was furious about the peaceful outcome. He left his father and went home to Cambridge. He wanted to gather more money for a new campaign. But he fell ill and died the next month. Eustace's death removed a clear claimant to the throne. This was politically helpful for those seeking peace. It is possible Stephen had already thought about passing over Eustace. Historian Edmund King notes that Eustace's claim was not mentioned in the Wallingford talks. This might have added to Eustace's anger.

Fighting continued after Wallingford, but half-heartedly. Stephen lost the towns of Oxford and Stamford to Henry. This happened while the King was fighting Hugh Bigod in eastern England. But Nottingham Castle survived an Angevin attempt to capture it. Meanwhile, Stephen's brother Henry of Blois and Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury worked together. They tried to make a lasting peace between the two sides. They pressured Stephen to accept a deal. The armies of Stephen and Henry FitzEmpress met again at Winchester. The two leaders would confirm the peace terms in November. Stephen announced the Treaty of Winchester in Winchester Cathedral. He recognized Henry FitzEmpress as his adopted son and successor. In return, Henry would show homage to him. Stephen promised to listen to Henry's advice but kept all his royal powers. Stephen's remaining son, William, would show loyalty to Henry. He would give up his claim to the throne. In exchange, his lands would be safe. Key royal castles would be held for Henry by guarantors. Stephen would have access to Henry's castles. And the many foreign soldiers would be sent home. Stephen and Henry sealed the treaty with a kiss of peace in the cathedral.

Death

Stephen's choice to recognize Henry as his heir was not necessarily the final end to the civil war. Stephen might have lived many more years. Henry's position in Europe was not completely safe. Stephen's son William was not ready to challenge Henry in 1153. But the situation could have changed later. There were rumors in 1154 that William planned to kill Henry. Historian Graham White calls the Treaty of Winchester a "precarious peace." Most modern historians agree the situation in late 1153 was still uncertain.

Many problems still needed to be solved. Royal power had to be brought back to the provinces. The complex issue of who controlled disputed lands after the war needed fixing. Stephen became very active in early 1154. He traveled widely around the kingdom. He started issuing royal orders for south-west England again. He traveled to York and held a major court. He wanted to show northern barons that royal power was returning. After a busy summer in 1154, Stephen went to Dover. He was meeting Thierry, Count of Flanders. Some historians believe the King was already ill. He might have been preparing to settle his family affairs. Stephen became ill with a stomach disease. He died on October 25 at the local priory. He was buried at Faversham Abbey with his wife Matilda and son Eustace.

Legacy

After Stephen's Reign

After Stephen's death, Henry II became King of England. Henry strongly brought back royal authority after the civil war. He tore down castles and increased royal income. But some of these changes had already started under Stephen. The destruction of castles under Henry was not as dramatic as once thought. And while he restored royal income, England's economy stayed much the same under both kings. Stephen's son William was confirmed as the Earl of Surrey by Henry. He did well under the new king, though there were occasional tensions. Stephen's daughter Marie I, Countess of Boulogne, also lived after her father. Stephen had placed her in a convent. But after his death, she left and married. Stephen's middle son, Baldwin, and second daughter, Matilda, had died before 1147. They were buried at Holy Trinity Priory, Aldgate. Stephen likely had three illegitimate sons: Gervase, Abbot of Westminster, Ralph, and Americ. Their mother was his mistress, Damette. Gervase became abbot in 1138. But after his father's death, Henry removed him in 1157, and he died soon after.

How We Know About Stephen

Much of what we know about Stephen's reign comes from writers who lived in or near the mid-12th century. These writings give us a good picture of the time. All the main writers had their own biases. Several key stories were written in south-west England. These include the Gesta Stephani, or "Acts of Stephen," and William of Malmesbury's Historia Novella, or "New History." In Normandy, Orderic Vitalis wrote his Ecclesiastical History, covering Stephen's rule until 1141. Robert of Torigni wrote a later history of the rest of the period. Henry of Huntingdon, who lived in eastern England, wrote the Historia Anglorum. This gives a regional view of the reign. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was past its best by Stephen's time. But it is remembered for its strong description of conditions during "the Anarchy." Most of these writings show some bias for or against Stephen, Robert of Gloucester, or other key figures. Those writing for the church after Stephen's later reign, like John of Salisbury, saw the King as a tyrant. This was because of his arguments with the Archbishop of Canterbury. But churchmen in Durham saw Stephen as a savior. This was because he helped defeat the Scots at the Battle of the Standard. Later writings during Henry II's reign were generally more negative. Walter Map, for example, called Stephen "a fine knight, but in other respects almost a fool." Many official documents called "charters" were issued during Stephen's reign. These often give details of events or daily life. Modern historians use them a lot.

Historians in the "Whiggish" tradition, which started in the Victorian era, saw English history as a steady path of political and economic progress. William Stubbs focused on the government aspects of Stephen's reign in his 1874 book. This started a lasting interest in Stephen. Stubbs's ideas, focusing on the disorder, led his student John Round to use the term "the Anarchy." This label is still used today, though sometimes debated. The scholar Frederic William Maitland also suggested that Stephen's reign might have been a turning point in English law.

Stephen is still a popular topic for history study. David Crouch says that after King John, Stephen is "arguably the most written-about medieval king of England." Modern historians have different opinions of Stephen as a king. R. H. C. Davis's book shows a weak king. He was a good military leader, active and pleasant. But "beneath the surface... mistrustful and sly," with poor strategic judgment. This ultimately hurt his reign. Stephen's lack of good policy decisions and poor handling of international affairs led to losing Normandy. This also meant he could not win the civil war. This is also highlighted by another writer, David Crouch. Historian Edmund King paints a slightly more positive picture than Davis. He concludes that Stephen was stoic, religious, and friendly. But he was rarely his own man. He usually relied on stronger people like his wife, Matilda, and brother Henry. Historian Keith Stringer gives a more positive view of Stephen. He argues that Stephen's failure was due to outside pressures on the Norman state. It was not because of his personal flaws.

Stephen in Stories

Stephen and his reign sometimes appear in historical fiction. Stephen and his supporters are in Ellis Peters' detective series The Cadfael Chronicles. These stories are set between 1137 and 1145. Peters shows Stephen's reign as a local story, focused on Shrewsbury. Peters portrays Stephen as a tolerant and fair ruler. This is despite him executing Shrewsbury's defenders in 1138. In contrast, he is shown negatively in Ken Follett's novel The Pillars of the Earth and its TV mini-series.

Issue

Stephen of Blois married Matilda of Boulogne in 1125. They had five children:

- Baldwin (died in or before 1135)

- Matilda (died before 1141), married in childhood to Waleran de Beaumont, Count of Meulan

- Eustace IV, Count of Boulogne (c. 1130 – 1153), ruled Boulogne 1146–1153

- William I, Count of Boulogne (c. 1135 – 1159), ruled Boulogne 1153–1159

- Marie I, Countess of Boulogne (c. 1136 – 1182), ruled Boulogne 1159–1182

King Stephen's illegitimate children by his mistress Damette included:

- Gervase, Abbot of Westminster

- Ralph

- Amalric

|

See also

In Spanish: Esteban de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Esteban de Inglaterra para niños