Fencepost limestone facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Fencepost limestoneStratigraphic range: Turonian ~93.9–93.9Ma |

|

|---|---|

Limestone endpost with leaner, an icon of Kansas

|

|

| Type | Geological marker bed |

| Unit of | Greenhorn Formation |

| Underlies | Carlile Formation |

| Overlies | Uppermost beds of the Greenhorn Formation |

| Thickness | 9–14 inches (0.23–0.36 m) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Chalky limestone (coccolithic) |

| Other | Microsparry calcite matrix Inoceramus shells and fragments Yellow, orange, or brown stainings and nodules of Limonite |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Extent | Outcrops from the Nebraska border near Mahaska, Kansas, about 200 miles southwest to a few miles from Dodge City, Kansas. Recorded in well logs throughout the High Plains. |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Use as stone fenceposts |

| Named by | F. W. Cragin |

| Year defined | 1896 |

The Fencepost limestone, also called Post Rock limestone or Stone Post, is a special layer of rock found in the Great Plains. It is famous for its historical use as fencing and building material in north-central Kansas. This stone helped create a unique look for the region.

This stone comes from the very top layer of the Greenhorn Limestone formation. It is a very important marker bed for geologists. It was also a popular building material in the late 1800s and early 1900s in Kansas. The stone was perfect for building in areas without many trees. It gives many old stone buildings in the region a cool rust-orange color.

But its most famous use is for the many miles of stone fence posts along country roads. This is why the area is known as Stone Post Country. You can even find the Post Rock Scenic Byway and Lincoln Center, Kansas is called "The Post Rock Capital of Kansas." Even today, this rustic stone is used in Kansas landscaping.

Discovering the Fencepost Limestone

The Fencepost limestone is a fairly thin but strong layer of rock. It forms the middle part of the bluffs in the Smoky Hills area of north-central Kansas. You can find it from the Nebraska border near Mahaska, Kansas, stretching about 200 miles southwest to near Dodge City, Kansas. It's visible in many farm and city buildings there.

This limestone is special because of how much it shaped the look of Kansas. Miles of stone fence posts line fields and pastures. When the first European settlers arrived, the dry climate and the grazing of buffalo, along with Plains Indians' burning practices, meant there wasn't much wood for building or fences. Luckily, a good, easy-to-dig stone was available. It's said that no other place in the world used a single rock type so much for fencing.

The Fencepost limestone is the very top layer of the Greenhorn Limestone. It marks the clear boundary between the Pfeifer Shale (below it) and the Fairport Chalk (above it).

F. W. Cragin first wrote about the "Fencepost limestone" in 1896. He first tried to name it "Downs limestone." It was also called "Benton limestone" because it was a key marker for the older "Benton Group" rock classification.

In 1897, W. N. Logan reported that there were 50,000 stone posts in Mitchell and Lincoln counties alone. The name "Fencepost limestone bed" became very well known. Most of the stone was used for fences and buildings between 1884 and 1920.

On July 1, 2018, Kansas made the Greenhorn Limestone formation, especially its "post rock" bed, the official state rock of Kansas.

How People Used the Stone

Fencing Fields

When Europeans settled in north-central Kansas, they found vast grasslands. With few trees available, they quarried a thin, shallow bed of Cretaceous limestone for buildings, bridges, and fenceposts. No area of the world has used a single rock formation so extensively for fencing. Today that rock layer is called Fencepost limestone and north-central Kansas is known as the Land of the Post Rock.

In early Kansas, farmers had to protect their crops from roaming cattle. In other parts of the country, farmers used wood from cleared fields to build split-rail fences. But Kansas had very few trees. This was because of millions of buffalo grazing and the way Plains Indians managed the land. The only wood available was along river banks.

In eastern Kansas, farmers could use large, hard stones from hills to build stone walls. But in central Kansas, most of the rock was soft shale or chalk. However, one special stone layer was perfect for fence posts. Making the posts took work, and they were heavy (about 250 to 450 pounds). But with the new invention of barbed wire, only one post was needed every 30 feet or so.

It was fairly easy to make strong stone posts from Fencepost limestone. The rock layer wasn't buried deep, so it didn't take much effort to uncover. Freshly dug slabs were soft and easy to shape. The stone only became hard after being removed from the ground and drying in the air. The natural rock layer doesn't have many cracks, so long rows of posts or large slabs could be split off without breaking. No heavy machines were needed, and local blacksmiths could easily make the right tools.

Some of the oldest stone post fences have stood for over 100 years. But by the 1920s, it became more expensive to make and install stone posts than to use factory-made steel or treated wood posts. When old stone fences are taken down, the posts are often reused. They are popular for landscaping or as strong corner posts in new fences.

Today, another type of stone called Permian top-ledge Cottonwood Limestone is sometimes shaped to look like Kansas Stone Posts. You can see examples at the Kansas Veterans' Cemetery in Wakeeny. These "fake" post rocks look different because they are all white, have tiny fossils called fusulinids, and don't have the iron stains or Cretaceous mollusk fossils found in real Fencepost limestone.

- Post Rock fences of Kansas

-

Stone posts with "sheep fencing", Munjor

-

Recreated stone post fence at the Santa Fe Trail Center

-

Post rock fencing near Liebenthal.

How the Stone Was Dug Out

Kansas's stone fenceposts were made from bluffs cut by rivers through the Blue Hills. In these hills, the limestone layer could be reached by removing a shallow layer of dirt. Digging out the stone left a long trench, about 10 to 20 feet wide, where water could collect after rain.

Traditionally, posts were made by drilling rows of holes directly into the soft, freshly exposed limestone. Workers would then put "feathers and wedges" into the holes and hammer the wedges to split off the posts. The posts were usually left with their rough, natural look, so the drill holes often remained visible. Later, building blocks were dug out the same way, so drill holes are often seen in old buildings unless the stone was smoothed.

Today, traditional hole splitting can still be used in Fencepost limestone quarries, especially if a rustic look is wanted. However, the stone is also cut in place with saws, depending on the desired finish.

- Quarrying Stone Posts from the Fencepost Limestone

Building with Stone

Fencepost limestone was a popular building material in the region. It looks yellowish to buff with orange or brown streaks. Over many decades, when exposed to the weather, it can turn almost white. People started using this limestone for buildings even before they realized it could be used for fenceposts.

Early settler homes on the treeless prairie were often dugouts or sod houses. Buying lumber was expensive, especially if it had to be shipped from far away. The Greenhorn Formation has many limestone layers, but most are too thin, soft, or fragile for permanent buildings. The Fencepost layer, however, is thick enough and easy to shape into strong, beautiful building blocks. It resists erosion better than the shale above it, so it forms wide bluffs or plateaus. This means it's easy to find and dig out. It was also fireproof, which was important when people used kerosene lamps and coal stoves.

Normally, Fencepost limestone was laid flat in buildings. So, you usually only see fossils in thin cross-sections on the walls. When laid this way, the stone shows its unique red-orange or brown lines. Many buildings still show the drill holes from when the stone was split. The Ellis County courthouse is a large building made of sawed Fencepost limestone. It's rare to see this stone laid vertically, but when it is, it can show off the fossils inside. For example, the First United Methodist Church of Hays, built in 1949, has Fencepost limestone cut into slabs and set vertically. You can see well-preserved cross-sections of its special fossil, Collignoniceras woollgari, in a few spots.

The use of Post Rock in buildings decreased in the 1920s as concrete became more common. However, it saw a comeback in the 1930s for public buildings built as WPA projects. Some newer buildings also used Fencepost limestone, often with sawn and vertically laid stone, like the Guaranty State Bank in Beloit (1958) and the Gross Field House and Coliseum at FHSU (1960s and 1975).

- Fencepost Limestone Constructions of Kansas

-

St. Anthony Church

Schoenchen -

Fort Fletcher Stone Arch Bridge, 1938

Ellis County -

Hart House, Beloit

-

Fossil Station Museum,

Russell -

Jewell County courthouse

Mankato

Using Stone in Landscaping

People love the look of stone post fencing, and the unique colors and rough texture of the stone. So, posts and limestone blocks are now used in modern landscaping, even far from where they are dug. Often, old posts from torn-down fences are reused. Blocks of Fencepost limestone are also taken from old buildings. New stone is also dug out just for landscaping and decorative items.

- Fencepost Limestone in Landscaping

-

Sign: Woodrow Wilson Elementary School, Manhattan

-

Stone bench from a thicker section of the bed, Ellis County

-

Convenience store landscaping, Lawrence

-

Retaining wall, Riley County

Stone Sculptures

We’ve got the highest quality quarried limestone anywhere right here.

Fencepost limestone is only about a foot thick and has a fine grain. It has been used in some public sculptures. Because it can be made into large slabs, it's good for bas-relief (sculptures that stick out slightly from a flat surface). This technique lets artists use the different tones in the stone.

John Linenberger, a sculptor from Victoria, used this technique in a carving on the convent next to St. Fidelis Church. He carved through the brown layer to show the lighter stone inside. Hays sculptor Peter "Fritz" Felten, Jr., used the same method for plaques on his Monarch of the Plains sculpture at the Fort Hays State Historic Site.

More recent sculptures by Pete Felten, like Train Hwy (1995) and Pteranodon (2000), show how the different tones of the Post Rock can be used. This stone can have darker brown outer layers and a lighter inner core. In Pteranodon, displayed near Interstate 70, the dinosaur's head is carved from brown Fencepost limestone. Its crest and bill are made from the lighter inner core.

You can also see this two-tone effect in stone slab sculptures at the Fossil Station Convenience Store in Russell. The weathered Post Rock here is very white, but has a black top layer and a red inner core. One carving shows a buffalo, with shallow cuts into the blackened layer to suggest its dark hide. Another carving shows a Hereford cow, which has a red body and white face. The stone is carved to show the red color against the white face and horns.

California sculptor Fred Whitman has carved several sculptures from old Stone Posts. Near Lucas, Fred carved faces of four local residents into four Stone Posts that stand in fences along the Post Rock Scenic Byway.

- Sculptures in two-tone Fencepost Limestone

-

A Post Rock Hereford (1992) [Christie]

Russell, Kansas

- Kansas Stone Post Iconography

-

Harvest Time at Kansas Museum of History

Finding Oil and Gas

The Fencepost limestone is also useful in exploring for oil and gas. Even though it's too thin to hold much oil or gas itself, it's located near other layers that do. The Fencepost shows a unique "double-peak" pattern in electric well logs. This pattern helps geologists find oil and gas layers in several states north and west of Kansas. Because of this, the Fencepost bed is used as a fixed reference point for mapping underground rock layers in the High Plains.

What the Stone is Made Of

The Fencepost bed is a chalky limestone rich in shells and tiny fossils called coccoliths. It's similar to other thin limestones in the Greenhorn and Carlile formations. However, this bed is made stronger by a crystalline matrix of calcite. This makes it more resistant to weathering and erosion.

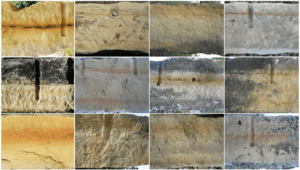

When it's first dug out, the Fencepost is olive-gray. When exposed to air, it turns light gray. If it's exposed for a long time, it becomes buff and yellow-orange, with one or more orange, rust, or brown streaks. This color comes from limonite (rust), which is an iron oxide. This is a small effect from volcanic activity during the Sevier orogeny. The limonite creates different shades and patterns, as seen in the collage on the right. This color can be barely visible or show up as one, two, or more shaded zones.

The exposed stone often develops a natural crack or "parting seam." This seam, also seen in the collage, was used to split the limestone into thinner slabs for paving. Limonite often gathers along this seam, sometimes forming small lumps or concretions. The top and bottom surfaces of the post can turn black after being exposed to weather above ground for a long time.

How to Identify the Fencepost Limestone

The Fencepost limestone bed is very important, almost like a separate rock formation. It's usually easy to find and identify. The Fencepost outcrop always forms a bench, bluff, or plateau. You can see great examples in the bluffs along Wilson Lake. There's a specific, reliable sequence of shale, limestone, and bentonite marker beds below the Fencepost.

Geologists found it convenient to use the Fencepost as the top boundary of one rock formation (Greenhorn) and the bottom boundary of another (Carlile). The rock layers that formed the steep bluff below the Fencepost were named the Greenhorn Formation. The layers that formed the low rolling hills above the Fencepost were named the Carlile Formation.

The Fencepost limestone is just one thin, chalky limestone bed among many similar ones. It's not the only one with an orange streak, and it's not even the thickest limestone bed in these formations. However, it is thicker than most other local limestones and is especially resistant to weathering. This is why it forms the tops of the central ridges and plateaus of the Smoky Hills.

Special Features for Identification

You can identify the Fencepost limestone in nature and in buildings by its unique look and contents. You can also look for other geological features nearby that confirm its identity.

The "Fencepost" limestone creates a clear ledge in the Blue Hills part of the Smoky Hills. Both above and below the Fencepost are areas with unusual, flattened, round or oval limestone concretions. About 6 feet (2 meters) below the Fencepost is a small but important marker bed called the "Sugar Sand." This is a 1 to 2 inch thick bentonite seam filled with "sand" made of calcite crystals. This "Sugar Sand" clearly identifies the Fencepost limestone above it.

- Fencepost bed markers in the Pfeifer Shale

Other Nearby Stone Layers

In the field, other nearby limestone layers might look similar to the Fencepost limestone. Some of these have even been used for fencing or building. However, these are also important marker beds, and their features can help you find and identify the Fencepost by comparing them.

- The Shellrock bed of the Jetmore Limestone (about 17 to 20 feet below the Fencepost) looks a lot like the Fencepost. It's the most used stone after the Fencepost for both fences and buildings. You can tell it apart because it's usually a bit thicker than the Fencepost and has many, many more Inoceramus labiatus shells. It also tends to form a ledge or terrace below the one made by the Fencepost. In posts and buildings, Shellrock is light gray to white and doesn't have limonite stains. Shellrock also has many natural cracks and tends to spall (break into flakes), so the slopes below it are covered with broken I. labiatus fossils.

- The "limestone above the Fencepost" (about 4 feet above the Fencepost) looks like a thinner version of the Fencepost in color and hardness. It's tough enough to be called a limestone. When it weathers, it doesn't turn as orange as the chalks higher up. Instead of I. labiatus, its main fossils are thin, calcite-filled belemnites. In nature, this limestone touches a 2-inch thick bentonite marker bed (F-1). In construction, this limestone was used for bricks, paving, or coping (the top layer of a wall). To dig out an area of Fencepost limestone, you usually have to dig out an equal area of this F-2 limestone first. The Jewell County Jail is an example where Fencepost limestone layers are mixed with layers of this F-2 limestone.

- The third Fairport marker bed (about 17 feet above the Fencepost) is a limestone that can also be very noticeable. It often forms the highest edge of the bluff, higher and set back from the actual Fencepost outcrop. In nature and in buildings, it's thinner and not quite as strong. It doesn't have mollusk shells and has a more uniform yellow-orange color instead of streaks.

- There's a connection between the Fort Hays Limestone and the thin Fencepost bed. The Fort Hays Limestone is a very obvious geological boundary in Kansas. The bluffs of Fencepost limestone are always found 5–40 miles south or east of the Fort Hays limestone bluffs. Fort Hays Limestone has been used in buildings and somewhat for fenceposts. However, when it touches soil, it absorbs a lot of moisture and can break apart in winter freezes. The Fencepost, on the other hand, is very durable when placed in the ground and was used for foundations. For example, some churches in Ellis and Hays have outer walls made of Fort Hays Limestone, but their foundations are built from Fencepost limestone.

Ancient Sea Life (Fossils)

The Fencepost limestone bed is one of the best places to see marine fossils from the Cenomanian and Turonian ages. You can find them especially in vertically laid stone walls, fenceposts, landscaping pieces, and paving stones. The fossils found in the Fencepost limestone are the same invertebrate fossils found in the Pfeifer Shale below it, and they also continue into the lower Fairport Chalk above it.

These specific index fossils help identify the Fencepost bed and tell it apart from other limestone beds. The easiest fossil to spot is Inoceramus (Mytiloides) labiatus, a type of clam. Other common Fencepost fossils include Inoceramus cuvieri, Collignoniceras woollgari (a type of ammonite), Baculites yokoyamai (a straight-shelled ammonite), and Pseudoperna bentonensis (a type of oyster).

- Fossils in the Fencepost Limestone

-

Calcite petrified wood inside a stone fence post

Visiting Post Rock Country

There are many places to see Stone Post Country, including rock outcrops, fences, and buildings, which you can explore by car.

Along Interstate 70

Interstate 70 goes right through the middle of Post Rock Country. You'll start seeing stone posts about 20 miles west of Salina, as the highway enters the scenic Dakota Escarpment. Stone fenceposts and buildings made of Fencepost limestone are common from there westward for about 70 miles, past Hays. You can take side trips into many Post Rock communities. Between mile 223 and mile 195, among the wind turbines, the Interstate is at the same level as the Fencepost outcrop. Between Exit 221 (Lucas) and Exit 219 (Ellsworth), Avenue B is a frontage road with exposed Fencepost limestone. You can see the thin bentonite marker bed below the Stone Post layer here. You might also find fragments of Inoceramus labiatus, Inoceramus cuvieri, Collignoniceras woollgari, and Baculites yokoyamai. Please do not collect from this public location.

Post Rock Scenic Byway

The Post Rock Scenic Byway connects the Post Rock towns of Wilson and Lucas. From Wilson, the highway climbs to the Fencepost outcrops, then drops into the colorful Dakota Hills south of the lake. Crossing the dam, you can see the Fencepost bluffs of the Blue Hills along the Saline Valley.

Lucas is now known for its folk art community and is home to Samuel P. Dinsmoor's Cabin Home and Garden of Eden statuary garden. Instead of traditional stone blocks, Dinsmoor imagined building homes with "logs" cut from the Fencepost bed, shaped to fit together like logs in a log cabin.

U.S. Highway 183

U.S. Highway 183 connects with Interstate 70 at Hays. Several public buildings, churches, and university buildings in Hays are built with Fencepost limestone.

North of Hays, Highway 183 enters the Fort Hays Limestone region, so you won't see Fencepost limestone there. However, south of Hays, the highway passes through the small Post Rock communities of Schoenchen, Liebenthal, and La Crosse. Near Schoenchen, stone posts were cut from long quarries along the bluff north of the river. On the plain between the Smoky Hill River and Liebenthal, the Fencepost bed is shallow and can be seen in ditches along the highway.

Old Quarry Site

U.S. 183 cuts through an abandoned Fencepost quarry as it nears the Smoky Hill River bridge near Schoenchen. Just uphill from the quarry, limestone and shale from the Fairport Shale are exposed in the road cut. Looking west from the highway, the quarry is south of the red utility warning signs. The Fencepost is not well exposed here, as most of it has been dug out. A strong marker bed of the Fairport Chalk (F-3) is visible a short distance up the hill. You can view the quarry from the fence line along the road cut. A limestone shelf sticks out from the old quarry face, but this is not the Fencepost. This visible limestone is the "limestone above the Fencepost" (Fairport Chalk marker F-2). This limestone is about half as thick as the Fencepost and can split along a limonite seam. It's almost as durable as the Fencepost and similar in color, so it was used for paving.

Post Rock Museum

The Post Rock Museum is located at the south end of La Crosse. Examples of Post Rock fill the park that this museum shares with the Rush County Historical Museum (in the relocated Timken train station), the Nekoma Bank Museum, and the Kansas Barbed Wire Museum. The Post Rock Museum has a recreated stone post quarry, old quarrying tools, and a fossil collection.

Active Stone Post Quarries

Vonada Farms and Stone Company is located 6.5 miles north of Sylvan Grove, Kansas. You can arrange tours through the Kansas Sampler Foundation pages.

Bluestem Quarry and Stoneworks operates near Lucas, Kansas.

Other Communities to Visit

Other towns with many Fencepost limestone buildings:

- Beloit

- Burr Oak

- Hunter

- Jamestown

- Jetmore

- Lincoln

- Paradise

- Pfeifer

- Randall

- Sylvan Grove

- Victoria

- Walker

Towns where Fencepost limestone meets Dakota sandstone:

Images for kids

-

Grants Villa

Ellis County -

Jewell County jail

Mankato -

Fox Theater Pavilion, Hays

-

E. W. Norris Service Station – Castle Lodge

(Glen Elder) -

Arthur Larkin House

Ellsworth -

Lincoln County courthouse

(Lincoln) -

Paradise Water Tower, 1938

(Paradise) -

Danske Evangelist Lutheran Kirke

Denmark -

Midland Hotel, Wilson

-

St. John the Baptist Catholic Church

(Beloit)

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |