History of Charleston, South Carolina facts for kids

The history of Charleston, South Carolina, is a long and interesting story that goes back hundreds of years to its first settlement in 1670. Charleston was one of the most important cities in the Southern United States from the time it was a colony until the Civil War in the 1860s. The city became rich by exporting crops like rice and, later, cotton. It was home to many wealthy merchants and landowners. Charleston was a major center for slavery in America.

After the Civil War, Charleston lost some of its power, but it remained important for South Carolina's economy. In the late 1800s, politicians from other parts of the state sometimes criticized Charleston's old-fashioned, wealthy ways. By the 1900s, Charleston started to become known as a cultural hub. In the 1920s, a period called the Charleston Renaissance brought many artists, writers, and people interested in history together to improve the city. Efforts to protect historic buildings began in the 1940s.

During and after World War II, Charleston became a very important naval base. The navy, shipyards, medical industries, and tourism helped the city's economy grow throughout the 20th century. Today, tourism and other service industries are the main drivers of Charleston's economy.

Contents

Early History of Charleston: 1670–1775

How Charleston Began and Grew

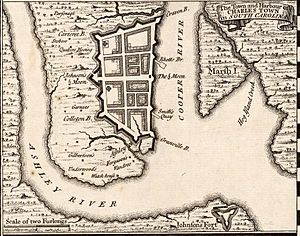

After becoming king again, King Charles II gave the Carolina territory to eight loyal friends, called the Lords Proprietors, in 1663. Seven years later, in 1670, the first settlement was made by English colonists from Bermuda. They called it "Charles Town." It was first located on the west bank of the Ashley River.

The leader of the Lords Proprietors, Anthony Ashley Cooper, wanted Charles Town to become a "great port town." By 1681, the settlement had grown with new people from England, Barbados, and Virginia. It then moved to its current location on a peninsula. As the capital of the Carolina colony, Charles Town was a key spot for expanding the colony. It was also the southernmost English settlement in North America during the late 1600s.

The settlement often faced attacks from both land and sea. Countries like Spain and France tried to take control of the region and attacked the town. Native Americans and pirates also raided it. For example, in 1706, an attack during Queen Anne's War failed. To protect themselves, the colonists built a fortification wall around the small town. Two buildings from this walled city still stand today: the Powder Magazine, which stored gunpowder, and the Pink House, which was likely an old tavern.

A plan from 1680, called the Grand Modell, laid out the new settlement as a "regular town." Land at the corner of Meeting and Broad Streets was set aside for a public square. Over time, this area became known as the Four Corners of the Law. This name referred to the important government and religious buildings located there.

In May 1718, Charles Town was attacked by the famous pirate Blackbeard for almost a week. His pirates stole from merchant ships and captured the passengers and crew of one ship. They demanded a chest of medicine from Governor Robert Johnson. After getting the medicine, they released their hostages and sailed away.

St. Philip's Episcopal Church, Charleston's oldest church, was built on the southeast corner of the square in 1752. The colony's capitol building was built across the square the next year. Its grand design showed how important Charleston was in the British colonies. The provincial court met on the first floor, while the assembly and governor's council met on the second floor.

By 1750, Charleston was a busy trade center. It was the main hub for trade in the southern colonies and the richest and largest city south of Philadelphia. By 1770, it was the fourth largest port in the colonies, after Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Its population was 11,000, with more than half being enslaved people. Crops like cotton, rice, and indigo were grown successfully by Gullah people. These enslaved people were brought from West Africa, especially from rice-growing regions. They were forced to work in the surrounding coastal areas. The colonists in South Carolina and Georgia used farming methods that relied heavily on the skills of their African slaves. Cotton, rice, indigo, and naval supplies were exported, making the shipping industry very profitable. Charleston became the cultural and economic heart of the South. Over time, the enslaved people developed their own unique Gullah language and culture, keeping many traditions from West Africa.

On May 4, 1761, a large tornado briefly emptied the Ashley River and sank five warships offshore.

Different People and Religions

While most early settlers came from England, colonial Charleston was also home to many different ethnic and religious groups. In colonial times, Boston, Massachusetts, and Charleston were like sister cities. Wealthy people would spend summers in Boston and winters in Charleston. There was a lot of trade with Bermuda and the Caribbean, and some people moved to Charleston from these islands. People from French, Scots-Irish, Scottish, Irish, and Germans also moved to the growing city. They belonged to many different Protestant churches, as well as Roman Catholicism and Judaism.

Many Sephardic Jews moved to Charleston. By the early 1800s, Charleston had the largest and wealthiest Jewish community in North America. The Coming Street Cemetery, started in 1762, shows how long Jewish people have been part of the community. The first Anglican church, St. Philip's Episcopal Church, was built in 1682. It was later destroyed by fire and rebuilt in its current spot.

Enslaved people made up a large part of the population and were active in the city's religious life. Free black Charlestonians and enslaved people helped start the Old Bethel United Methodist Church in 1797. The Emanuel A.M.E. Church began from a religious group formed by African Americans, both free and enslaved, in 1791. It is the oldest A.M.E. church in the South and the second oldest in the country. The first American museum opened to the public in Charleston on January 12, 1773.

From the mid-1700s, many people moved to the upcountry areas of the Carolinas. Some came through Charleston from other countries, but many also moved south from Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Eventually, the upcountry population became larger than the coastal population. Charlestonians often saw the upcountry people as less refined, and they had different interests. This led to many disagreements between the upcountry and the wealthy Charleston elite for several generations.

Charleston's Culture

As Charleston grew, so did its cultural and social opportunities, especially for wealthy merchants and plantation owners. The first theater building in America, the Dock Street Theatre, was built in Charleston in 1736. It was later replaced by the 19th-century Planter's Hotel, where rich plantation owners stayed during Charleston's horse-racing season. Today, it is again the Dock Street Theatre, known as one of the oldest active theaters built for stage performances in the United States.

Different ethnic groups formed helpful societies: the South Carolina Society (French Huguenots, 1737), the German Friendly Society (1766), and the Hibernian Society (Irish immigrants, 1801). The Charleston Library Society was started in 1748 by wealthy Charlestonians who wanted to keep up with new ideas in science and philosophy. This group also helped create the College of Charleston in 1770. It is the oldest college in South Carolina and the oldest city-run college in the United States.

The Role of Slavery

In the early 1600s, it was hard to get enslaved Africans north of the Caribbean. To meet labor needs, European colonists had practiced enslaving Native Americans for some time. The people of Carolina changed the Native American slave trade in the late 1600s and early 1700s by selling enslaved Native Americans, mostly to the West Indies. Historian Alan Gallay estimates that between 1670 and 1715, between 24,000 and 51,000 Native Americans were captured and sold from South Carolina. This was more than the number of African slaves brought to the future United States during the same period.

A major start of African slavery in the North American colonies happened with the founding of Charleston (originally Charles Town) and South Carolina in 1670. The colony was mainly settled by planters from the island colony of Barbados, who brought many African slaves with them from that island.

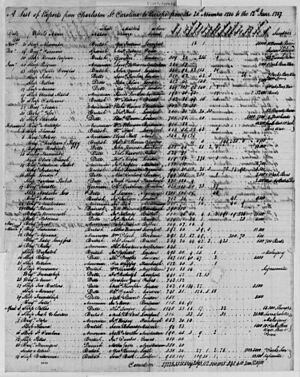

By the mid-1700s, Charlestown was a major center for the Atlantic slave trade for England's southern colonies. Even with a ten-year pause, its customs office handled about 40% of the African slaves brought to North America between 1700 and 1775. This continued to be about half until the official end of the African slave trade in 1808, though many enslaved people were still illegally brought in after that date.

American Revolution: 1775–1783

As problems grew between the colonists and England, Charleston became a key place in the American Revolution. To protest the Tea Act of 1773, which meant "taxation without representation," Charlestonians took tea and stored it in the Exchange and Custom House. In 1774, representatives from across the colony met at the Exchange to choose delegates for the Continental Congress. This group was responsible for writing the Declaration of Independence. South Carolina declared its independence from the British king on the steps of the Exchange. Soon, the church steeples of Charleston, especially St. Michael's, became targets for British warships. The rebel forces painted the steeples black to hide them at night.

The British attacked Charleston three times. The British believed many colonists would support the King, but white southerners had largely lost faith in Britain. This was partly because of British legal cases that threatened to free enslaved people and military actions that did the same. However, these actions did win the support of thousands of Black Loyalists.

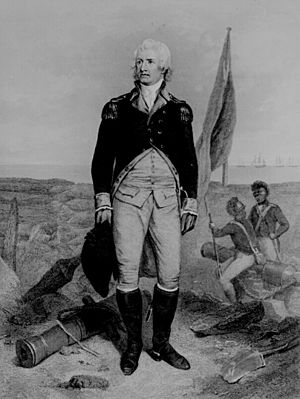

On June 28, 1776, General Henry Clinton, with 2000 men and a navy fleet, tried to capture Charleston. He hoped that Loyalists in South Carolina would rise up and help. But the plan failed because the navy was defeated by the Continental Army at Fort Moultrie. This was under the command of William Moultrie. When the British ships fired cannonballs, the shots could not break through the fort's thick walls, which were made of palmetto logs. Also, no local Loyalists attacked the town from behind as the British had hoped. The Loyalists were not well organized enough to help.

The Battle of Sullivan's Island saw 9 British ships and 2000 soldiers fail to capture a partially built fort from a few hundred American militia members. This happened on June 28, 1776. The fort's defenses, made of spongy palmetto wood and sand, completely stopped the British naval attack. This was the Royal Navy's first defeat in 100 years. The Liberty Flag used by Moultrie's men later became the basis for the South Carolina flag. The victory's anniversary is still celebrated as Carolina Day.

After capturing Savannah in late 1778, British forces moved towards Augusta. In April 1779, British General Prévost sent 2500 men towards South Carolina. This forced Moultrie's militia to retreat towards Charlestown. Prévost's men faced little resistance until they were 10 miles from the city. But an intercepted message told Prévost that American General Lincoln was returning. Prévost began to retreat. The main battle of this event was his rearguard's successful defense at Stono Creek on June 20. The expedition mainly caused anger among both allies and enemies because of its uncontrolled raiding.

Clinton returned in 1780 with 14,000 soldiers. American General Benjamin Lincoln was trapped and surrendered all 5400 of his men after a long fight. The Siege of Charleston was the biggest American defeat of the war. The British made capturing Charlestown their main goal. Gen. Lincoln knew about the attack and began to fortify the city. However, an outbreak of smallpox meant that local slaveholders did not send men to help. After getting more troops, Gen. Clinton began his siege on April 1, 1780, with about 14,000 troops and 90 ships. Bombardment started on March 11. Lincoln held out until May 12, when his surrender became the greatest American defeat of the war. Gen. Clinton left Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis in Charleston with about 3000 troops to secure British control and then move north.

Several Americans escaped and joined militias led by figures like Francis Marion, known as the 'Swampfox,' and Andrew Pickens. These militias used surprise attacks and targeted British supporters. Clinton returned to New York, leaving Cornwallis with 8000 men to gather Loyalists, build forts, and demand loyalty to the King. Many of these forts were later taken by the Patriot militias. British rule was weakened by its changing policies and disagreements. As a result, South Carolinians lost faith in Charleston's restored British government long before the British defeat at Yorktown and their departure in late 1782.

Charleston After the Revolution: 1783–1861

After the British and Loyalist leaders left, the city officially changed its name to Charleston in 1783.

Trade and Growth

By 1788, South Carolinians met at the Capitol building for the Constitutional Ratification Convention. While there was support for the new Federal Government, there was disagreement over where the new state capital should be. A suspicious fire broke out in the Capitol building during the Convention. After this, the delegates moved to the Exchange and decided that Columbia would be the new state capital. By 1792, the Capitol had been rebuilt and became the Charleston County Courthouse. Once it was finished, the city had all the public buildings needed to change from a colonial capital to the center of the antebellum South. The grand and numerous buildings built in the next century showed the hope and pride many Charlestonians felt for their community.

Charleston became more successful in the plantation-based economy after the Revolution. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 completely changed how cotton was produced, and it quickly became South Carolina's main export. Cotton plantations relied heavily on enslaved labor. Enslaved people were also the main workforce within the city, working as house servants, skilled workers, market sellers, or laborers. Many black Charlestonians spoke Gullah, a language that mixed African, French, German, Jamaican, English, Bahamian, and Dutch words. In 1807, the Charleston Market was founded. It soon became a central place for the African-American community, with many enslaved and free people of color working at stalls.

By 1820, Charleston's population grew to 23,000, with a majority of black residents. In 1822, a huge slave revolt planned by Denmark Vesey, a free black man, was discovered. This caused great fear among white Charlestonians. As a result, the activities of free black people and enslaved people were severely limited. Hundreds of black people, both free and enslaved, and some white supporters involved in the planned uprising were held in the Old Jail. This event also led to the building of a new State Arsenal in Charleston. Recently, some historians have questioned how accurate the stories about Vesey's planned revolt are.

As Charleston's government, society, and businesses grew, financial institutions were created to support the city's goals. The Bank of South Carolina, the second oldest building built as a bank in the nation, was established in 1798. Branches of the First and Second Bank of the United States were also in Charleston in 1800 and 1817. While the First Bank became City Hall by 1818, the Second Bank was very important because it was the only bank in the city that could handle international transactions, which were vital for the export trade. By 1840, the Market Hall and Sheds, where fresh food was brought daily, became the city's main business center. The slave trade also depended on the port of Charleston, where ships could unload and enslaved people were sold at markets. However, enslaved people were never traded at the Market Hall areas.

Political Changes

In the first half of the 1800s, South Carolinians became more convinced that states' rights were more important than the Federal government's power. Buildings like the Marine Hospital caused arguments about how much the Federal government should be involved in South Carolina's government, society, and business. During this time, over 90 percent of Federal money came from taxes on imported goods, collected by custom houses like the one in Charleston. In 1832, South Carolina passed a law called nullification. This allowed a state to cancel a Federal law, and it was aimed at the latest tax acts. Soon, Federal soldiers were sent to Charleston's forts and began to collect taxes by force. A compromise was reached where the taxes would be slowly lowered, but the basic argument over states' rights continued to grow in the following decades. Charleston remained one of the busiest port cities in the country. The building of a new, larger Custom House began in 1849, but its construction was stopped by the Civil War.

Before the 1860 election, the National Democratic Convention met in Charleston. Hibernian Hall was the main place for delegates who supported Stephen A. Douglas. They hoped he could bridge the gap between northern and southern delegates on the issue of allowing slavery in new territories. The convention broke apart when delegates could not get enough votes for any candidate. This division led to a split in the Democratic Party and the election of Abraham Lincoln, the Republican candidate.

Civil War: 1861–1865

On December 24, 1860, the South Carolina General Assembly voted to leave the Union. On January 9, 1861, cadets from Citadel fired the first shots of the American Civil War. They shot at the Union ship Star of the West, which was entering Charleston's harbor with supplies for Fort Sumter. The fort was already under siege. On April 12, 1861, shore batteries led by General Pierre G. T. Beauregard opened fire on the Union-held Fort Sumter in the harbor. After 34 hours of bombing, Major Robert Anderson surrendered the fort. Officers and cadets from The Citadel were assigned to different Confederate batteries during the attack on Fort Sumter. The Citadel continued to operate as a school during the Civil War. Its cadets, along with those from the Arsenal Academy in Columbia, formed the Battalion of State Cadets. Cadets from both schools helped the Confederate army by training new soldiers, making ammunition, protecting weapons, and guarding Union prisoners.

On December 11, 1861, a huge fire burned 164 acres of Charleston. This included the Cathedral of St John and St Finbar, South Carolina Institute Hall, the Circular Congregational Church, and many of the city's best homes. This fire caused much of the destruction seen in Charleston at the end of the war.

In December 1864, Citadel and Arsenal cadets were ordered to join Confederate forces at Tullifinny Creek, South Carolina. There, they fought intense battles with advancing units of General W. T. Sherman's army and suffered eight casualties.

Overall, The Citadel Corps of Cadets earned eight battle streamers and one service streamer for its help to South Carolina during the war. The city, under siege, controlled Fort Sumter and became a center for ships trying to sneak past the Union blockade. It was also the site of the first successful submarine attack on February 17, 1864. The H.L. Hunley made a daring night attack on the USS Housatonic. In 1865, Union troops moved into the city and took control of many places, such as the United States Arsenal, which the Confederate army had taken at the start of the war. The War Department also took over the grounds and buildings of The Citadel Military Academy. It was used as a federal military base for over 17 years until it was returned to the state and reopened as a military college in 1882.

On April 14, 1865, thousands of people traveled to Charleston to watch Union Major General Anderson raise the same flag at Fort Sumter that he had lowered on April 13, 1861.

After the Civil War: 1865–1945

Rebuilding Charleston

After the Confederacy lost the war, Federal forces stayed in Charleston during the city's rebuilding period. The war had destroyed the city's wealth. Formerly enslaved people faced poverty and unfair treatment. Slowly, new businesses helped the city and its people regain energy and grow. As the city's trade improved, Charlestonians also worked to restore their community's important places.

In 1867, Charleston's first free high school for black students, the Avery Institute, was started. General William T. Sherman supported turning the United States Arsenal into the Porter Military Academy. This was a school for former soldiers and boys who had lost their families or homes because of the war. Porter Military Academy later joined with Gaud School and is now a K-12 prep school, Porter-Gaud School. The William Enston Homes, a planned community for the city's elderly and sick, was built in 1889. J. Taylor Pearson, a formerly enslaved man, designed the Homes and lived there peacefully for years as the maintenance manager after the rebuilding period. A grand public building, the United States Post Office and Courthouse, was finished in 1896. This showed new life in the heart of the city.

The 1886 Earthquake

On August 31, 1886, Charleston was almost destroyed by an earthquake. The earthquake was very strong, estimated at a magnitude of 7.0. It caused major damage up to 60 miles away and structural damage hundreds of miles from Charleston. It was felt as far away as Boston, Chicago, New Orleans, Cuba, and Bermuda. It damaged 2,000 buildings in Charleston and caused $6 million worth of damage. At that time, all the buildings in the city were only valued at about $24 million.

Early 1900s to 1945

In the early 1900s, strong political groups appeared in the city. These groups showed the tensions between different economic classes, races, and ethnic groups. Almost all of them were against U.S. Senator Benjamin Tillman, who often criticized the city on behalf of poor farmers from the upstate. Well-organized groups within the Democratic Party in Charleston gave voters clear choices and played a big role in state politics.

The Charleston riot of 1919, which involved white people attacking black people, was the worst violence in Charleston since the Civil War.

From 1920 to 1940, the city became a national leader in protecting historic buildings. The city council created the nation's first historic district zoning laws in 1931. This was mainly because modern gas stations were being built in old residential areas. People in Charleston wanted to protect their city's unique look. They felt that preserving historic places helped them deal with the negative parts of modern industrial society and allowed them to be proud of their city, even if it wasn't as rich as some northern cities.

During World War II, the focus on historic preservation was paused. Charleston became one of the country's most important naval bases. It was filled with sailors, service members, construction workers, and new families. The Charleston Naval Shipyard reached its highest employment of 26,000 people in July 1943. High wages boosted the economy, but limits on new housing led to severe overcrowding. For the first time, women and African Americans were hired in large numbers to work in the Navy Yard and related industries, including well-paying skilled jobs.

Modern Charleston: 1945–Present

Hurricane Hugo

Hurricane Hugo hit Charleston in 1989. Although the worst damage was in nearby McClellanville, the storm damaged three-quarters of the homes in Charleston's historic district. The hurricane caused over $2.8 billion in damage.

The Joe Riley Era

Since he was elected mayor in 1975, Joe Riley was a strong supporter of bringing back Charleston's economic and cultural importance. The last thirty years of the 1900s saw major new investments in the city. There were many city improvements and a strong commitment to protecting historic places. These efforts continued even after Hurricane Hugo. Joe Riley did not run for reelection in 2016.

The downtown medical district is growing quickly with new biotechnology and medical research industries. All the major hospitals are also expanding a lot. More expansions are planned or happening at other major hospitals in the city and surrounding area, such as Bon Secours-St Francis Xavier Hospital, Trident Medical Center, and East Cooper Regional Medical Center.

African-American History in Charleston

Slavery To Civil Rights: A Walking Tour of African-American Charleston (2018) includes these important sites:

- 1919 Race Riot: Five African-Americans were killed in downtown Charleston.

- Avery School: A very important school for African-Americans.

- Dr. Lucy Hughes Brown (1863–1911): The first African-American woman doctor in South Carolina and the first woman doctor in Charleston.

- Brown Fellowship Society: A group that helped its members.

- Cigar workers strike: The first time the song "We Shall Overcome" was used.

- Denmark Vesey Slave Revolt, 1822: A planned uprising by enslaved people.

- Edwin Harleston (1882–1931): A painter and co-founder of Charleston's NAACP chapter.

- Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church: Founded in 1816.

- Freedman's Savings Bank and Trust Company: A bank for formerly enslaved people.

- Jehu Jones Hotel: Jones was a Lutheran minister who had been born enslaved.

- PFC Ralph H. Johnson (1949–1968): Awarded the Medal of Honor after his death.

- Ernest Everett Just (1883–1941): A famous cell biologist.

- Gadsden's Wharf: The place where about 30,000 enslaved Africans were brought to the U.S.

- Kress Lunch Counter Sit-in, 1960: A protest against segregation.

- Louis Gregory (1874–1951): A civil rights pioneer and teacher of the Bahá'í faith.

- Grimké Sisters: Childhood home of Sarah Moore Grimké (1792–1873) and Angelina Emily Grimké (1805–1879), who worked to end slavery.

- Jenkin's Band: A group that trained many generations of black musicians.

- Philip Simmons (1912–2009): A skilled artist in ironwork.

- Porgy & Bess: A "folk opera" by Gershwin, set in Charleston.

- Robert Smalls (1839–1915): Escaped slavery by stealing a Confederate ship; later became a Congressman.

- Ryan's Slave Mart: A place where enslaved people were sold (see Old Slave Mart).

- Septima Clark (1898–1987): Martin Luther King Jr. called her the mother of the Civil Rights Movement.

See also

- American urban history

- Charleston in the American Civil War

- Charleston, South Carolina – main article

- History of the Jews in Charleston, South Carolina

- List of newspapers in South Carolina: Charleston

- Timeline of Charleston, South Carolina

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |