History of Indianapolis facts for kids

The history of Indianapolis is a fascinating story that spans over 200 years! This important city was founded in 1820. Before that, the land belonged to the Lenape (Delaware Nation), a Native American tribe. In 1821, a small settlement near the White River became the main town for Marion County and was chosen as the future capital of Indiana. It officially became the state capital on January 1, 1825.

Early European American settlers arrived around 1819 or 1820, drawn by the chance to buy federal lands. Indianapolis grew quickly because of its central location in Indiana and the wider Midwest. Its flat, fertile land made it a great place for farming. The White River helped power early mills, and when railroads arrived in 1847, Indianapolis became a major center for factories and transportation. Important roads like the National Road also connected it to other big cities.

Alexander Ralston and Elias Pym Fordham designed the original city plan in 1821. Their plan started from Governor's Circle, now known as Monument Circle, right in the middle of town. Even today, you can still see this original "Mile Square" layout in downtown Indianapolis, even though the city has grown much larger. When the White River turned out to be too shallow for big boats and a planned canal wasn't finished, railroads became super important. They helped Indianapolis become a hub for business, industry, and manufacturing. The city is still the state capital and a key center for banking and insurance, which started way back in its early days. People in Indianapolis also began creating many groups for religion, culture, and charity to help others and remember the state's history.

Contents

- How Indianapolis Began (Before 1820)

- Planning the City's Layout

- Early Years (1820–1860)

- Indianapolis During the Civil War (1861–1865)

- Growth and Change (1866–1900)

- The Industrial Era (Early 1900s)

- Economic Growth and Natural Resources

- The Role of African Americans in Indianapolis History

- Unigov: Merging City and County Governments

- Images for kids

How Indianapolis Began (Before 1820)

Indianapolis was chosen to be Indiana's new state capital in 1820. But before that, the area was home to the Lenape (Delaware Nation) tribe, who lived along the White River. This area was mostly flat and covered in thick woods, providing lots of food and wild animals. Some parts were a bit swampy. The White River and Fall Creek offered water and good fishing. The Native Americans didn't build permanent towns right here, but they did set up temporary camps, especially near the rivers.

Back in 1787, the Northwest Ordinance created the Northwest Territory, which included what is now Indiana and Indianapolis. As Indiana moved closer to becoming a state, its territory got smaller. In 1816, the year Indiana became a state, the U.S. Congress gave four pieces of federal land to create a permanent state capital. Two years later, in 1818, the Treaty of St. Mary's meant the Delaware tribe gave up their land in central Indiana and agreed to leave by 1821. This land included the spot chosen for the new state capital.

New federal lands for sale in central Indiana attracted many settlers, mostly from northwestern Europe. While many were Protestants, some early Irish and German immigrants were Catholics. Not many African Americans lived in central Indiana before 1840. The first permanent European American settlers in the Indianapolis area were likely the McCormick or Pogue families. Historians often say John Wesley McCormick and his family were the first, building a cabin along the White River in February 1820.

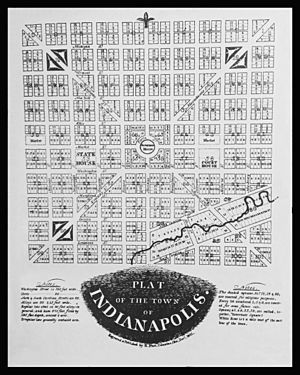

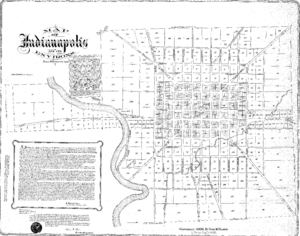

Planning the City's Layout

On January 11, 1820, Indiana's government chose a committee to pick a spot for the new state capital. They picked Alexander Ralston and Elias Pym Fordham to survey and design the town plan for Indianapolis in 1821. Ralston had helped design Washington, D.C., so he knew a lot about city planning.

Ralston's original plan for Indianapolis was a square mile, often called the "Mile Square." It was bordered by North, East, South, and West Streets (though they weren't named yet). In the very center was Governor's Circle, a large round area. This circle later became known as Monument Circle, after the huge Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument was finished there in 1901. This impressive monument is 284 feet (86.5 meters) tall!

Ralston's plan included wide roads and public squares spreading out from the center. It also had four diagonal streets, which are now called avenues. Public squares were meant for government and community use. Ralston even adjusted his grid pattern in one area to fit the flow of Pogue's Run, a local creek.

Today, Ralston's basic street plan is still clear in downtown Indianapolis, even though the city has grown much bigger. Streets in the original plan were named after states that were part of the U.S. at the time, plus Michigan, which was a territory. For example, Washington Street, a wide east-west road, is part of the historic National Road that crossed Indiana. Meridian and Market Streets cross the Circle. Not many street improvements were made in the early days; sidewalks didn't appear until 1839 or 1840.

Once the city plan was ready, land was divided into lots and sold starting October 8, 1821. Money from these sales helped build a statehouse, a courthouse, and offices for the governor and state treasurer.

Early Years (1820–1860)

Indianapolis quickly became important for politics as Indiana's capital. But it also grew into a major railroad hub and a center for community and cultural activities.

How the City Was Governed

Indianapolis became the seat of county government on December 31, 1821, when Marion County, Indiana, was created. The city and county shared a government until 1832, when Indianapolis became an official town run by five elected leaders. It became an incorporated city on March 30, 1847. Samuel Henderson was the city's first mayor, leading a seven-member city council.

On January 1, 1825, the state government moved to Indianapolis from Corydon, Indiana. The Indiana General Assembly held its first meeting in the new capital on January 10, 1825. Indianapolis also hosted many important political events. For example, in 1840, the country's first Whig convention met here. Famous people like former U.S. president Martin Van Buren and politician Henry Clay visited in 1842. Abraham Lincoln first visited the city in 1859.

Keeping People Safe and Healthy

Early on, the city worked to provide military protection, law enforcement, fire safety, and public health. Some efforts had federal help, while others were local, often by volunteers.

In 1822, a federal militia was formed for central Indiana. Indianapolis got its first rifle and artillery companies in 1826. The city council created Indianapolis's first police department in 1854. The Indianapolis Fire Company, started in 1826, was the town's first volunteer fire department. A regular, paid fire department was established in 1859.

Because Indianapolis is near the White River and Fall Creek, low-lying areas often flooded. Heavy rains caused floods in 1821, 1824, 1828, and 1847. Poor drainage and sanitation in the early days led to illnesses like malaria, influenza, cholera, and smallpox. To fight these, doctors formed a medical society in 1823, and the town appointed its first health board in 1831. The Indiana Hospital for the Insane opened in 1847. City Hospital's first building was finished in 1859, and it served as a military hospital during the Civil War.

Getting Around: Transportation

Indianapolis was founded on the White River, but people soon realized the river was too shallow for large boats like steamboats. After 1831, no steamboat successfully reached the capital city. A planned canal system, the Indiana Central Canal, was started in 1836 but never fully finished because the state ran out of money in 1839. Only about 7 to 9 miles (11 to 14 km) of the canal were opened for traffic, connecting Indianapolis to Broad Ripple.

Road construction was more successful. The National Road, a major east-west road, reached Indianapolis in 1837. Stagecoach service connected Indianapolis to cities like Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio. The Michigan Road also passed through Indianapolis.

The first steam railroad in Indiana, the Madison and Indianapolis line, arrived in Indianapolis on October 1, 1847. By 1850, eight rail lines reached the city, ending its isolation and bringing new growth. In the 1850s, Indianapolis became a major transportation hub, boosting trade and development. The city's first Union railroad depot, which served many different railroads, opened in 1853.

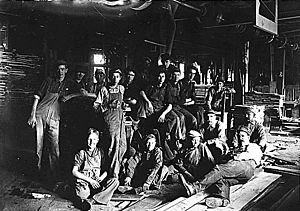

Businesses and Factories

In the early years, manufactured goods came by wagons or boats. But most local farm products weren't sent outside Indianapolis until railroads arrived in the 1850s. Most early businesses were on Washington Street. The first market house was built in 1833, which later became the Indianapolis City Market. Farming was very important, and the first Indiana State Fair was held in Indianapolis in 1852.

Before railroads, there weren't many mills or factories. One of the earliest gristmills (for grinding grain) was built in 1821. The Indianapolis Steam Mill Company, the town's first official business, opened a mill in 1831. Other early businesses included sawmills, flourmills, and a wool factory. The first foundry (for metal casting) opened in 1833, and the first brewery in 1834. With better rail transport in the 1850s, more factories were built, including meat-packing plants. Iron manufacturing also grew. The city's first gasworks was completed in 1851, providing natural gas for lighting.

Banking and insurance companies also started early, though some didn't last long. The State Bank of Indiana opened an office in Indianapolis in 1834.

Religious Groups and Churches

Baptists, Presbyterians, and Methodists formed Indianapolis's first church groups in the 1820s. Other groups like Episcopalians, Disciples of Christ, Lutherans, Catholics, Quakers, and Jewish congregations were also established before the Civil War. Many early church buildings are gone, but some congregations still exist, though they might have new names or locations.

Indianapolis's early African American and German communities also started their own churches. The oldest African Methodist Episcopal Church congregation formed in 1836. Second Baptist Church (1846) was the first Baptist church for African Americans. Germans in Indianapolis started several German-speaking churches, like Zion Church (1841) and Saint Marienkirche (1856), the city's first German-language Catholic parish.

Schools and Community Groups

Private schools started in the 1820s, but free public schools didn't appear until the 1840s. Voters approved taxes for public schools in 1847, but they closed in 1857 after a court ruling and didn't reopen until 1861.

However, private and state-funded schools continued. The state took over a private school for the deaf in 1844, renaming it the Indiana State Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb. The Indiana Institute for the Education of the Blind opened in 1847. North Western Christian University, which later became Butler University, opened in 1855.

People in Indianapolis also created many groups to help the community and preserve history. The Indiana State Library (1825) and the Indiana Historical Society (1830) were formed to save state and local history. The city also got public lecture halls and libraries. By the 1850s, there were new meeting places like the Grand Lodge of the Free Masons and the first Bates House hotel. Entertainment included music, plays, and art shows. German immigrants also started clubs and cultural societies, like the Indianapolis Maennerchor (1854), the city's oldest German-language music club.

Early News and Diaries

Newspapers started in Indianapolis in the 1820s to report local, state, and national news. Early papers included the Indianapolis Gazette (1822) and the Daily Sentinel (1841), which was the city's first daily newspaper. Some papers focused on specific topics, like the Indiana Freeman (1844), an antislavery newspaper. German-speaking residents also had their own newspapers.

We know a lot about early Indianapolis from the diary of Calvin Fletcher, an important early resident. His diary, from 1817 to 1835, recorded daily events and his thoughts on law, business, and farming. It also detailed early railroads, banks, schools, and charities. Fletcher's diary is a key source for understanding life in Indianapolis during its first 45 years.

Indianapolis During the Civil War (1861–1865)

During the American Civil War, Indianapolis strongly supported the Union (the North). After the Battle of Fort Sumter, people in Indianapolis declared their loyalty. Governor Oliver P. Morton quickly made Indianapolis a gathering place for Union army troops. On April 16, 1861, orders were given to form Indiana's first regiments and gather volunteer soldiers in Indianapolis. Within a week, over 12,000 recruits from Indiana signed up to fight for the Union.

Indianapolis became a very important railroad hub and transportation center during the war. Twenty-four military camps were set up near the city. Camp Morton was a major prisoner-of-war camp for captured Confederate soldiers starting in 1862. A state-owned arsenal was built in 1861, and a permanent federal arsenal in 1862. Homes for Union soldiers and their families were also established. Several local places, including City Hospital, cared for wounded soldiers. Crown Hill National Cemetery, a national military cemetery, was created in Indianapolis in 1866.

More than 60% of Indiana's army regiments were organized and trained in Indianapolis. About 4,000 men from Indianapolis and Marion County, Indiana, served in 39 regiments. Many different groups formed units, including German-American and Irish-American regiments. The 28th Regiment United States Colored Troops, the only black regiment formed in Indiana during the war, trained in Indianapolis.

City residents supported Union soldiers by providing food, clothing, and supplies, even with rising prices and shortages. Local aid groups and the Indiana Sanitary Commission raised money and gathered supplies for troops. People in Indianapolis also helped prisoners at Camp Morton and cared for sick and wounded soldiers.

During the war, Indianapolis's population grew from 18,611 in 1860 to 45,000 by the end of 1864. New businesses and industries brought more jobs. For example, Gilbert Van Camp started his canning business in 1861, and Kingan Brothers, a meatpacking company, opened in 1863. The city's first mule-drawn streetcar line began operating in 1864. Even with growth, street crime was common, leading the city to increase its police force.

The Civil War era also saw strong political disagreements between Indiana's Democrats and Republicans. People were suspicious of those who didn't fully support the Union. In May 1863, Union soldiers tried to break up a Democratic convention in Indianapolis, leading to an event jokingly called the Battle of Pogue's Run. Soldiers searched trains leaving the convention, and many delegates threw their weapons into Pogue's Run creek. Fear also spread during Morgan's Raid in July 1863, when Confederate forces came into southern Indiana, but they turned away from Indianapolis.

Other important events happened in Indianapolis during the war. On February 11, 1861, president-elect Abraham Lincoln visited Indianapolis on his way to his inauguration. During the war, Richard Jordan Gatling invented and tested his Gatling gun in Indianapolis. Lincoln's funeral train also stopped in Indianapolis on April 30, 1865, where over 100,000 people came to see the assassinated president's coffin at the Indiana Statehouse.

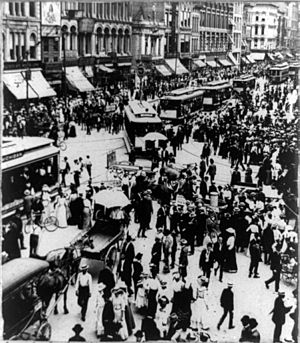

Growth and Change (1866–1900)

In the second half of the 1800s, Indianapolis grew incredibly fast. Its population jumped from 8,091 in 1850 to 169,164 in 1900! The city expanded in every direction, changing from a farming community to a busy industrial center. Many of Indianapolis's most famous buildings were constructed during this time, and some are still standing today. These include the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument (finished 1902), the Indiana Statehouse (1888), Union Station (1888), and the Das Deutsche Haus (1898).

The building of Indianapolis's belt railroad and stockyards in the late 1870s, the Indiana gas boom in the late 1880s, and more railroad traffic helped turn Indianapolis into a major industrial center in the Midwest. Many big railroads passed through the city. Between 1880 and 1900, the number of factories grew a lot, and the value of goods made in the city increased significantly. Major industries like food processing became very important. Kingan and Company, a large meatpacking plant, and Gilbert Van Camp's canning company (famous for pork and beans) were big employers. Indianapolis also became a center for banking and insurance. However, many workers faced tough conditions, low pay, and long hours, which led to the rise of labor unions.

More jobs in factories encouraged people to move to the city, including African Americans after the Civil War. Most new arrivals came from Indiana's rural areas. Immigrants from other countries included English, Irish, Germans, and later, people from eastern and southern Europe like Hungarians, Italians, and Greeks.

The late 1800s also brought improvements to Indianapolis's schools and public library. To train workers for factories, the Indianapolis Public Schools started manual training programs. In 1875, North Western Christian University moved and later changed its name to Butler University. Several private schools were also established. The Indianapolis Public Library opened in 1873 and moved to a new building in 1893. The city's first library branch opened in 1896.

Many new churches were built downtown. Some are still active today, like Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (1869) and Saint John the Evangelist Catholic Church (1867–71). The main office for the Catholic Church in the area moved to Indianapolis in 1878.

As the population grew, city leaders improved social services. City Hospital began accepting patients again in 1866 after being a military hospital. Methodist Hospital of Indianapolis was established in 1889. Other groups were formed to help the poor, the elderly, and children.

New neighborhoods like Woodruff Place and Irvington were created as the city expanded. Streetcars connected downtown to these new areas. However, Indianapolis still had poor areas. To keep order, the city gave police powers to private security guards for local businesses and the train station.

People in Indianapolis also enjoyed more entertainment. Theaters and performances were very popular, including plays, concerts, and circuses. Amusement parks, concert halls, and sports events were also popular. The "bicycle craze" arrived in the mid-1890s. Famous African American cyclist Marshall "Major" Taylor competed and won at the city's Newby Oval cycling track in 1898.

The city also began developing its Indianapolis Park and Boulevard System, a network of wide, tree-lined streets connected to city parks. Several early parks like Military Park, Fairview Park, Garfield Park, and Riverside Park were started during this time. The site of Camp Morton, a Civil War prison camp, became a fairgrounds again. The city government also took care of Governor's Circle (now Monument Circle) and created University Park (1876).

Many social clubs formed, encouraging community involvement and personal growth. Ethnic groups also built their own clubs, like Das Deutsche Haus (1898), which became a center for German culture.

Newspapers were also very important. The Indianapolis News started publishing the city's first evening newspaper in 1869. The Indianapolis Leader, believed to be the city's first African American newspaper, was founded in 1879.

The 1880s and 1890s were considered a "golden age" for Indianapolis. Benjamin Harrison, an Indianapolis resident, was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1881 and became president of the United States in 1888. This era also saw the beginning of Indiana's "golden age of literature," with popular authors like James Whitcomb Riley having ties to Indianapolis.

By 1900, Indianapolis had grown from a small farming town into a major industrial city in the Midwest. However, it still faced challenges like low wages for many workers, pollution from factories, and discrimination.

The Industrial Era (Early 1900s)

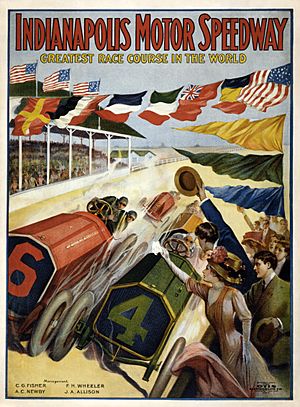

Just like in many American cities, the invention of the automobile led to a huge growth of suburbs around Indianapolis. For a few years, Indianapolis was a major center for car production, with companies like Duesenberg, Marmon, National, and Stutz. The famous automobile races at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway each year are a lasting reminder of this booming industry from the early 1900s.

With roads spreading out like spokes on a wheel, Indianapolis became a key hub for regional transportation, connecting to cities like Chicago, Louisville, and St. Louis. This is why Indiana's motto is "The Crossroads of America." Today, four major interstate highways cross in Indianapolis: I-65, I-69, I-70, and I-74. The city is a big trucking center, and its wide network of highways helps keep traffic flowing smoothly for a city its size.

A strike by streetcar workers began in Indianapolis in October 1913. The strike happened just before city elections, making it hard for many people to vote. The union wanted a law to protect their rights better. Governor Samuel Ralston eventually called out the entire Indiana National Guard and put the city under martial law (military control). On November 6, the governor spoke to the crowd of strikers, offering to remove the troops if they went back to work and negotiated peacefully. This ended the strike that day. The strike led to Indiana's first labor protection laws, including a minimum wage and better working conditions.

Economic Growth and Natural Resources

Indianapolis saw a period of great success at the start of the 20th century, with big steps forward in its economy, society, and culture. A lot of this was thanks to the discovery of a huge natural gas deposit in east-central Indiana in 1886, called the Trenton Gas Field. A few years later, oil was also found. The state government even offered free natural gas to factories that built there. This led to a sharp increase in industries like glass and automobile manufacturing. However, the natural gas ran out by 1912, and the oil production also dropped quickly. This brought an end to this "golden era." The 1920 census was the first to show that Indiana had more people living in cities than in rural areas.

The Role of African Americans in Indianapolis History

African Americans have played a very important part in Indianapolis's history. The city was a key stop on the Underground Railroad, a network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. Before the Great Migration in the early 1900s, Indianapolis had a higher black population (nearly 10%) than any other major city in the Northern States. Today, Indianapolis is considered one of the least segregated cities in the northern U.S., meaning many white and black residents live in the same neighborhoods.

The African-American community originally thrived in the lively Indiana Avenue neighborhood. This area became a center of black culture for the entire Midwest. It had a black Christian church by 1836 and most businesses were black-owned by 1865. A strong black middle class lived here, along with famous jazz musicians like Freddie Hubbard and Wes Montgomery.

Indianapolis also printed the nation's first illustrated black newspaper in 1888, called the Indianapolis Freeman. It was read across the country and was seen as a leading black journal in America.

In 1910, Madam C. J. Walker moved her cosmetics company to Indianapolis. Walker became America's first self-made woman millionaire and the richest African American of her time. Her successful career as a businesswoman and philanthropist is remembered at the Madame Walker Theatre Center on Indiana Avenue, which still offers entertainment today.

While Indianapolis had some segregated elementary schools in the early 1900s, high schools were not segregated until 1927. That's when Crispus Attucks High School was created, despite objections from the African-American community. However, even after school segregation was outlawed in Indiana in 1948, many African Americans were proud of Attucks. Its teachers often had advanced degrees. In 1955, Crispus Attucks, led by the legendary Oscar Robertson, became the first all-black high school in America to win an integrated state basketball championship. They won again in 1956, becoming the first team in Indiana to have a perfect undefeated season.

Today, Indianapolis is home to the Indiana Black Expo. The Indiana Black Expo Summer Celebration is the largest ethnic and cultural event in the United States. This ten-day event, held at the Indiana Convention Center and other places, brings African Americans to Indianapolis from all over the state and country. Started in 1970, the Black Expo offers networking, education, career, and cultural opportunities. In 2006, over 350,000 people attended.

Robert F. Kennedy's Speech

Years later, Indianapolis saw a historic moment in the Civil Rights Movement. On April 4, 1968, the day Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Robert F. Kennedy gave an unplanned speech about racial peace to a mostly African-American crowd in a poor Indianapolis neighborhood. Indianapolis was the only major American city that did not experience riots after the assassination.

Unigov: Merging City and County Governments

In 1970, Indianapolis merged most of its government services with those of Marion County. This was called "Unigov." This change mostly united Indianapolis with its nearby suburbs. Four communities within Marion County (Beech Grove, Lawrence, Southport, and Speedway) are partly outside of the Unigov system. Also, 11 other communities (called "included towns") are legally part of the Consolidated City of Indianapolis under Unigov.

These "included towns" follow the laws of the Consolidated City of Indianapolis. However, some still have their own property taxes and provide police or other services through contracts. Also, some local services like schools, fire, and police departments remained separate under Unigov. But the mayor of Indianapolis is also the mayor of all of Marion County, and the City-County Council makes laws for the entire county.

In 2005, a bill called Indianapolis Works was proposed to further combine city and county governments. A less complete version of the bill passed. It allowed the City-County Council to vote to combine the Indianapolis Police Department and the Marion County Sheriff's Department. It also allowed the Indianapolis Fire Department to merge with individual township fire departments if they agreed. The Washington Township Fire Department was the first to merge with the Indianapolis Fire Department on January 1, 2007.

Police consolidation was first rejected but then passed in December 2005. As of January 1, 2007, Indianapolis has a combined metropolitan police force. However, the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department is not the only police agency in Marion County. The four "excluded cities" (Beech Grove, Lawrence, Southport, and Speedway) still have their own police forces, as do many school districts and "included towns."

Images for kids

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |