History of Libya facts for kids

Libya has a long and interesting history, shaped by many different groups of people, including the native Berbers (also called Amazigh). The Amazigh people have lived in Libya for its entire history. For most of its past, Libya has been controlled by different foreign powers from Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The history of Libya can be divided into six main parts: Ancient Libya, the Roman era, the Islamic era, Ottoman rule, Italian rule, and the Modern era.

Contents

- Ancient Libya: From Green Lands to Desert

- Phoenician and Greek Settlements

- Persian and Egyptian Rule

- Roman Libya: A Time of Growth and Change

- Islamic Libya: New Rulers and Changes

- Ottoman Rule: Pirates and Pashas

- Italian Rule: A New Colonial Era

- The Kingdom of Libya: Independence Achieved

- Gaddafi's Rule: The Jamahiriya Era

- 2011 Uprising and the First Civil War

- Transition and the Second Civil War

- See also

Ancient Libya: From Green Lands to Desert

Thousands of years ago, the Sahara Desert, which now covers most of Libya, was a green land. It had lakes, forests, many kinds of animals, and a mild climate like the Mediterranean region. Old tools and other finds show that people lived on the coast as early as 8000 BCE. These people likely came because of the good climate, which helped their culture grow. They raised cattle and grew crops.

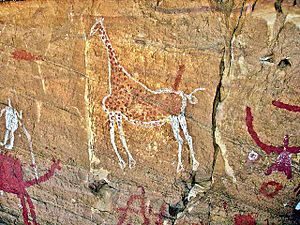

Ancient Egyptian writings from the Old Kingdom are the oldest records we have of the Berber people. These writings mention Berber tribes raiding the Nile Delta. Rock paintings found in places like Wadi Mathendous and the Jebel Acacus are the best sources of information about Libya's early history. They show a time when the Libyan Sahara had rivers, grassy areas, and lots of wildlife like giraffes, elephants, and crocodiles.

Later, a big change in climate made the "green Sahara" quickly turn into the Sahara Desert. This change caused people to spread out across Africa, from the Atlantic coast to the Siwa Oasis in Egypt.

The ancestors of the Berber people likely moved into the area by the Late Bronze Age. One of the earliest known tribes was the Garamantes, who lived in Germa, southern Libya. The Garamantes were a Saharan people of Berber origin. They used a clever underground watering system. They were probably in the Fezzan region around 1000 BCE and were a strong local power in the Sahara between 500 BCE and 500 CE. When the Phoenicians arrived from the East, the Lebu, Garamantes, Berbers, and other tribes were already well-established in the Sahara.

Phoenician and Greek Settlements

The Phoenicians were among the first to set up trading posts on Libya's coast. Merchants from Tyre (in modern-day Lebanon) traded with different Berber tribes. They made agreements to get raw materials. By the 5th century BCE, Carthage, the largest Phoenician colony, had taken control of much of North Africa. A unique culture, called Punic, grew there. Punic settlements on the Libyan coast included Oea (later Tripoli), Libdah (later Leptis Magna), and Sabratha. These cities were in an area later called Tripolis, or "Three Cities." Libya's capital, Tripoli, gets its name from this.

In 630 BCE, the Ancient Greeks settled in Eastern Libya and founded the city of Cyrene. Within 200 years, four more important Greek cities were built in the area known as Cyrenaica. These were Barce (later Marj), Euhesperides (later Berenice, now Benghazi), Taucheira (later Arsinoe, now Taucheria), Balagrae (later Bayda), and Apollonia (later Susa), which was Cyrene's port. Together with Cyrene, they were called the Pentapolis (Five Cities). Cyrene became a major center for learning and art in the Greek world. It was known for its medical school, academies, and buildings. The Greeks of the Pentapolis fought against attacks from the Ancient Egyptians in the East and the Carthaginians in the West.

Persian and Egyptian Rule

In 525 BCE, the Persian army of Cambyses II took over Cyrenaica. For the next two centuries, this area remained under Persian or Egyptian control. When Alexander entered Cyrenaica in 331 BCE, the Greeks welcomed him. Eastern Libya then came under Greek control again, as part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Later, the Pentapolis formed a group of cities usually ruled by a king from the Ptolemaic royal family.

Roman Libya: A Time of Growth and Change

After Carthage fell, the Romans did not immediately take over Tripolitania (the area around Tripoli). They left it under the control of Berber kings from Numidia. Later, the coastal cities asked for and received Roman protection. Ptolemy Apion, the last Greek ruler, gave Cyrenaica to Rome. Rome officially took control of the region in 74 BCE and joined it with Crete as a Roman province called Creta et Cyrenaica. During the Roman civil wars, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica supported Pompey and Marc Antony against Caesar and Octavian. The Romans finished conquering the region under Augustus, taking northern Fezzan with Cornelius Balbus Minor.

Tripolitania became very rich and reached its best time in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. The city of Leptis Magna, home to the Severan dynasty, was at its peak. Meanwhile, Cyrenaica's first Christian groups were formed by the time of Emperor Claudius. But it was badly damaged during the Kitos War and lost many Greeks and Jews. Even though Trajan repopulated it with military groups, it began to decline.

For over 400 years, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were part of a large Roman state. People shared a common language, legal system, and Roman identity. Roman ruins like those in Leptis Magna and Sabratha still stand in Libya today. They show how lively the region was. Busy cities and even smaller towns had all the features of Roman city life: forums, markets, public entertainment, and baths. Traders and craftspeople from many parts of the Roman world settled in North Africa. However, the cities of Tripolitania kept their Punic character, and Cyrenaica kept its Greek character. Tripolitania was a big exporter of olive oil. It was also a center for trading ivory and wild animals brought to the coast by the Garamantes. Cyrenaica remained an important source of wines and horses. Most of the people in the countryside were Berber farmers. In the west, they became very "Romanized" in language and customs. Until the 10th century, a form of Latin called African Romance was still used in some areas of Tripolitania, mainly near the Tunisian border.

When the Roman Empire declined, the old cities fell into ruin. This process was sped up by the destructive sweep of the Vandals through North Africa in the 5th century. The region's wealth decreased under Vandal rule. The old Roman political and social order, broken by the Vandals, could not be brought back. In distant areas ignored by the Vandals, people sought protection from tribal leaders. They got used to being independent and resisted joining the imperial system again.

When the Empire returned (now as the East Romans) as part of Justinian's efforts to retake lands in the 6th century, attempts were made to strengthen the old cities. But this was only a last effort before they fell into disuse. Cyrenaica, which had remained a Byzantine outpost during the Vandal period, also became like an armed camp. Unpopular Byzantine governors charged heavy taxes to pay for military costs, while towns and public services, including the water system, were left to fall apart. Byzantine rule in Africa did keep the Roman idea of imperial unity alive for another 150 years. It also stopped the Berber nomads from taking over the coastal region. By the early 7th century, Byzantine control was weak, Berber rebellions were more common, and there was little to stop Muslim invaders.

Islamic Libya: New Rulers and Changes

The Byzantine control over Libya was weak and limited to a few poorly defended coastal forts. So, when Arab horsemen first entered Cyrenaica in September 643 CE, they met little resistance. Under the command of 'Amr ibn al-'As, the armies of Islam conquered Cyrenaica and renamed the Pentapolis to Barqa. They also took Tripoli, but after destroying its Roman walls and getting a payment, they left. In 647, an army of 40,000 Arabs, led by Abdullah ibn Saad, permanently took Tripoli from the Byzantines. From Barqa, the Fezzan (Libya's southern region) was conquered by Uqba ibn Nafi in 663, and Berber resistance was overcome.

Over the next centuries, Libya was ruled by several Islamic dynasties. They had different levels of independence from the Ummayad, Abbasid, and Fatimid caliphates of the time. Arab rule was easily set up in the farming areas along the coast and in the towns, which grew rich again under Arab support. Townspeople liked the safety that allowed them to trade peacefully. The Punic farmers felt a connection with the Semitic Arabs, who they looked to for protection of their lands. In Cyrenaica, Christians who followed the Coptic Church welcomed the Muslim Arabs as liberators from Byzantine rule. The Berber tribes in the inner lands accepted Islam, but they resisted Arab political control.

For several decades, Libya was under the control of the Umayyad Caliph of Damascus. Then, the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads in 750, and Libya came under the rule of Baghdad. When Caliph Harun al-Rashid appointed Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab as his governor of Ifriqiya in 800, Libya gained a lot of local independence under the Aghlabid dynasty. The Aghlabids were careful rulers of Libya. They brought order to the region and fixed Roman irrigation systems, which made the area rich from farming.

By the end of the 9th century, the Shiite Fatimids controlled Western Libya from their capital in Mahdia. Later, they ruled the whole region from their new capital of Cairo in 972 and appointed Bologhine ibn Ziri as governor. During Fatimid rule, Tripoli grew rich from trading slaves and gold from Sudan. It also sold wool, leather, and salt to Italy, in exchange for wood and iron goods. Ibn Ziri's Berber Zirid dynasty eventually broke away from the Shiite Fatimids and recognized the Sunni Abbasids of Baghdad as the true Caliphs. In response, the Fatimids caused thousands of people from two troublesome Arab Bedouin tribes, the Banu Sulaym and Banu Hilal, to move to North Africa. This act greatly changed the Libyan countryside and made the region more Arab in culture and language. Ibn Khaldun noted that the lands ruined by the Banu Hilal invaders became completely dry desert.

Zirid rule in Tripolitania did not last long. Already in 1001, the Berbers of the Banu Khazrun broke away. Tripolitania remained under their control until 1146, when the Normans of Sicily took over the region. It was not until 1159 that the Moroccan Almohad leader Abd al-Mu'min took Tripoli back from European rule. For the next 50 years, Tripolitania saw many battles between the Almohad rulers and rebels from the Banu Ghaniya. Later, a general of the Almohads, Muhammad ibn Abu Hafs, ruled Libya from 1207 to 1221. After him, a Tunisian Hafsid dynasty was set up, independent from the Almohads. The Hafsids ruled Tripolitania for almost 300 years and traded a lot with European city-states. Hafsid rulers also supported art, literature, architecture, and learning. Ahmad Zarruq was one of the most famous Islamic scholars to settle in Libya during this time. By the 16th century, the Hafsids became more involved in the power struggle between Spain and the Ottoman Empire. After Habsburg Spain successfully invaded Tripoli in 1510 and handed it over to the Knights of St. John, the Ottoman admiral Sinan Pasha finally took control of Libya in 1551.

Ottoman Rule: Pirates and Pashas

After the Habsburgs of Spain invaded in the early 16th century, Charles V gave the defense of Tripoli to the Knights of St. John in Malta. Drawn by the piracy that spread along the Maghreb coast, adventurers like Barbarossa and his followers strengthened Ottoman control in the central Maghreb. The Ottoman Turks conquered Tripoli in 1551 under the command of Sinan Pasha. The next year, his successor Turgut Reis was named the Bey of Tripoli and later Pasha of Tripoli in 1556. As Pasha, he decorated and built up Tripoli, making it one of the most impressive cities on the North African coast. By 1565, the administrative power in Tripoli was given to a pasha appointed directly by the sultan in Constantinople. In the 1580s, the rulers of Fezzan swore loyalty to the sultan. Although Ottoman authority was not strong in Cyrenaica, a bey was placed in Benghazi late in the next century to act as the government's agent from Tripoli.

Over time, real power went to the pasha's group of janissaries, a self-governing military group. Eventually, the pasha's role became mostly ceremonial. Mutinies and coups were common. In 1611, the deys staged a coup against the pasha, and Dey Sulayman Safar was made head of government. For the next hundred years, a series of deys effectively ruled Tripolitania. Some ruled for only a few weeks. At different times, the dey was also the pasha-regent. The government led by the dey was independent in its internal affairs. Although it depended on the sultan for new janissary recruits, its government was allowed to follow its own foreign policy. The two most important Deys were Mehmed Saqizli (ruled 1631–49) and Osman Saqizli (ruled 1649–72), both also Pashas, who effectively ruled the region. Osman Saqizli also conquered Cyrenaica.

Tripoli was the only large city in Ottoman Libya (then called Tripolitania Eyalet) at the end of the 17th century. It had about 30,000 people. Most residents were Moors, as city-dwelling Arabs were known then. Several hundred Turks and renegades formed a ruling class. A large part of these were kouloughlis (meaning "sons of servants"—children of Turkish soldiers and Arab women). They cared about local interests and were respected by locals. Jews and Moriscos worked as merchants and craftspeople. A small number of European traders also visited the city. European slaves and many enslaved black people brought from Sudan were also part of daily life in Tripoli. In 1551, Turgut Reis enslaved almost all the people of the Maltese island of Gozo, about 6,300 people, sending them to Libya. The most common slavery involved black Africans brought through trans-Saharan trade routes. Even though the slave trade was officially ended in Tripoli in 1853, it continued in practice until the 1890s.

Without clear guidance from the Ottoman government, Tripoli fell into a period of military chaos. Coups happened often, and few deys stayed in power for more than a year. One such coup was led by a Turkish officer named Ahmed Karamanli. The Karamanlis ruled from 1711 until 1835, mainly in Tripolitania, but also had influence in Cyrenaica and Fezzan by the mid-18th century. Ahmed was a Janissary and a popular cavalry officer. He killed the Ottoman Dey of Tripolitania and took the throne in 1711. After convincing Sultan Ahmed III to recognize him as governor, Ahmed became pasha and made his position hereditary. Although Tripolitania continued to pay a small tribute to the Ottoman padishah, it acted as an independent kingdom. Ahmed greatly expanded his city's economy, especially by using corsairs (pirates) on important Mediterranean shipping routes. Nations that wanted to protect their ships from the corsairs had to pay tribute to the pasha. Ahmed's successors were not as skilled as he was. However, the region's delicate balance of power allowed the Karamanli to survive several family crises without being invaded. The Libyan Civil War of 1791–1795 happened during these years. In 1793, a Turkish officer named Ali Pasha removed Hamet Karamanli and briefly brought Tripolitania back under Ottoman rule. However, Hamet's brother Yusuf (ruled 1795–1832) brought back Tripolitania's independence.

In the early 19th century, war broke out between the United States and Tripolitania. A series of battles followed, known as the First Barbary War and the Second Barbary War. By 1819, various treaties from the Napoleonic Wars forced the Barbary states to almost completely stop piracy. Tripolitania's economy began to fall apart. As Yusuf weakened, groups formed around his three sons. Although Yusuf gave up his power in 1832 to his son Ali II, a civil war soon started. Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II sent troops, supposedly to restore order. Instead, he removed and exiled Ali II, ending both the Karamanli dynasty and an independent Tripolitania. However, order was not easily restored. The revolt of the Libyans under Abd-El-Gelil and Gûma ben Khalifa lasted until Gûma's death in 1858.

The second period of direct Ottoman rule brought administrative changes and seemed to create more order in the governance of Libya's three provinces. It was not long before the Scramble for Africa and European colonial interests turned their attention to Libya's less important Turkish provinces. The country was reunited through an invasion (Italo-Turkish War, 1911–1912) and occupation starting in 1911, when Italy turned the three regions into colonies.

Italian Rule: A New Colonial Era

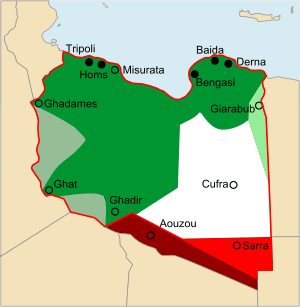

From 1912 to 1927, Libya was known as Italian North Africa. From 1927 to 1934, the territory was divided into two colonies, Italian Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitania, each run by Italian governors. About 150,000 Italians settled in Libya, making up roughly 20% of the total population.

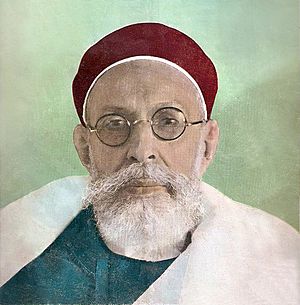

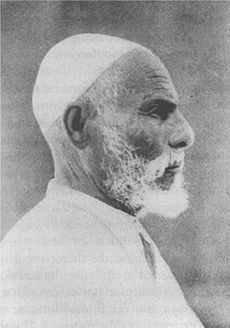

In 1934, Italy officially named the colony "Libya" (a name the Greeks used for all of North Africa except Egypt). This colony was made up of the three provinces of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania, and Fezzan. Idris al-Mahdi as-Senussi (later King Idris I), the Emir of Cyrenaica, led Libyan resistance against Italian occupation between the two world wars. Historian Ilan Pappe estimates that between 1928 and 1932, the Italian military "killed half the Bedouin population (either directly or through disease and starvation in camps)." Italian historian Emilio Gentile says about 50,000 people were victims of this harsh rule.

In 1934, the political area called "Libya" was created by Governor Balbo, with Tripoli as its capital. The Italians focused on improving infrastructure and public works. They greatly expanded Libya's railway and road networks from 1934 to 1940, building hundreds of kilometers of new roads and railways. They also encouraged new industries and many new farming villages.

During WW2, from June 1940, Libya was a central place for destructive fighting between the Axis and the British Empire. The Allies conquered all of Libya from Italy by February 1943.

From 1943 to 1951, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were under British military administration. The French controlled Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo. However, he did not permanently live in Cyrenaica until some foreign control was removed in 1947. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy gave up all claims to Libya.

The Kingdom of Libya: Independence Achieved

On November 21, 1949, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution stating that Libya should become independent before January 1, 1952. Idris represented Libya in the UN talks that followed. On December 24, 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya. It became a constitutional monarchy with King Idris as its only monarch.

In 1951, Libya's first Constitution was put into effect. The Libyan National Assembly wrote the Constitution and approved it in a meeting in Benghazi on October 7, 1951. Mohamed Abulas’ad El-Alem, the President of the National Assembly, and the two Vice-Presidents, Omar Faiek Shennib and Abu Baker Ahmed Abu Baker, signed and gave the Constitution to King Idris. It was then published officially.

This Constitution was very important because it was the first law to formally protect the rights of Libyan citizens after the country became a nation. After strong UN discussions where Idris argued that a single Libyan state would benefit Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica, the Libyan government wanted a constitution with many rights common in European and North American countries. Although it did not create a non-religious state (Article 5 says Islam is the State religion), the Libyan Constitution formally set out rights like equality before the law, equal civil and political rights, equal opportunities, and equal responsibility for public duties, "without distinction of religion, belief, race, language, wealth, kinship or political or social opinions" (Article 11).

During this period, Britain was involved in large engineering projects in Libya and was also the country's biggest supplier of weapons. The United States also kept a large Wheelus Air Base in Libya.

Gaddafi's Rule: The Jamahiriya Era

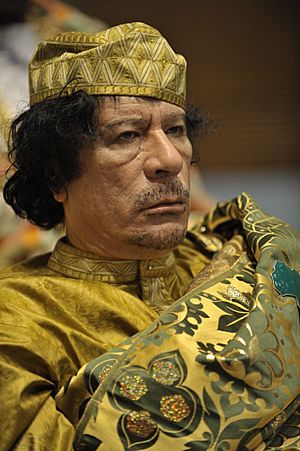

On September 1, 1969, a small group of military officers, led by 27-year-old army officer Muammar Gaddafi, carried out a coup d'état against King Idris. This started the Libyan Revolution. Gaddafi was called the "Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution" in government statements and the official Libyan press.

In 1973, Gaddafi gave a "Five-Point Address." He announced that all existing laws would be stopped and Sharia (Islamic law) would be put in place. He said the country would be cleaned of the "politically sick." A "people's militia" would "protect the revolution." There would be an administrative revolution and a cultural revolution. Gaddafi set up an extensive surveillance system. About 10 to 20 percent of Libyans worked in surveillance for the Revolutionary committees, which watched activities in government, factories, and schools. Gaddafi publicly executed people who disagreed with him, and these executions were often shown on state television. Gaddafi used his network of diplomats and recruits to kill many critical refugees around the world. Amnesty International listed at least 25 such killings between 1980 and 1987.

In 1977, Libya officially became the "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya." Gaddafi officially gave power to the General People's Committees and claimed to be only a symbolic leader. However, critics at home and abroad said these changes gave him almost unlimited power. People who disagreed with the new system were not tolerated, and Gaddafi himself approved punishments, including the death penalty. The new "jamahiriya" government structure he created was officially called a form of direct democracy, but the government refused to publish election results. Later that same year, Libya and Egypt fought a four-day border war, known as the Libyan-Egyptian War. Both nations agreed to a ceasefire with help from the Algerian president Houari Boumediène. In February 1977, Libya began to send military supplies to Goukouni Oueddei and the People's Armed Forces in Chad. The Chadian–Libyan conflict truly began when Libya's support for rebel forces in northern Chad grew into an invasion. Much of the country's oil income, which greatly increased in the 1970s, was spent on buying weapons and supporting many rebel groups around the world. An airstrike in 1986 failed to kill Gaddafi. Libya was accused in the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, and the 1989 bombing of UTA Flight 772 over Chad and Niger. Libya was finally put under United Nations sanctions in 1992. Gaddafi also funded various other groups, from anti-nuclear movements to Australian trade unions.

From 1977 onwards, the average income per person in Libya rose to over US$11,000, the fifth-highest in Africa. The Human Development Index became the highest in Africa and even higher than that of Saudi Arabia. This was achieved without taking any foreign loans, keeping Libya debt-free. Also, the country's literacy rate went from 10% to 90%. Life expectancy rose from 57 to 77 years. Job opportunities were created for migrant workers. Welfare systems were introduced that provided free education, free healthcare, and financial help for housing. The Great Manmade River was also built to provide free access to fresh water across large parts of the country. In addition, financial support was given for university scholarships and employment programs.

Gaddafi doubled the minimum wage, set official price controls, and made rents go down by 30% to 40%. Gaddafi also wanted to fight the strict social rules that had been placed on women by the previous government. He created the Revolutionary Women's Formation to encourage changes. In 1970, a law was introduced that said men and women were equal and insisted on equal pay. In 1971, Gaddafi supported the creation of a Libyan General Women's Federation. In 1972, a law was passed that made it illegal for any female under sixteen to marry and made sure a woman's agreement was needed for a marriage.

Gaddafi took the honorary title of "King of Kings of Africa" in 2008 as part of his plan for a United States of Africa. By the early 2010s, Libya was trying to take a leading role in the African Union. It was also seen as having closer ties with Italy, one of its former colonial rulers, than any other country in the European Union. The eastern parts of the country were "ruined" because of Gaddafi's economic ideas, according to The Economist.

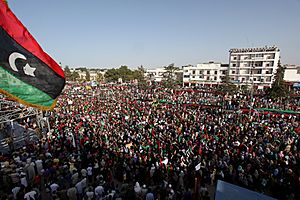

2011 Uprising and the First Civil War

After popular movements overthrew the rulers of Tunisia and Egypt, Libya's neighbors, a full-scale revolt began in Libya on February 17, 2011. By February 20, the unrest had spread to Tripoli. In the early hours of February 21, 2011, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, Muammar Gaddafi's oldest son, spoke on Libyan television. He feared that the country would break apart into "15 Islamic fundamentalist emirates" if the uprising spread. He admitted that "mistakes had been made" in stopping recent protests. He announced plans for a meeting to write a new constitution. But he warned that the country's economic wealth and recent prosperity were at risk. He also warned of "rivers of blood" if the protests continued.

On February 27, 2011, the National Transitional Council was formed. It was led by Mustafa Abdul Jalil, Gaddafi's former justice minister. Its goal was to manage the areas of Libya under rebel control. This was the first serious effort to organize the widespread opposition to Gaddafi's government. While the council was based in Benghazi, it claimed Tripoli as its capital. Hafiz Ghoga, a human rights lawyer, later became the council's spokesman. On March 10, 2011, France became the first country to officially recognize the council as the rightful representative of the Libyan people.

By early March 2011, some parts of Libya were no longer under Gaddafi's control. They were controlled by a group of opposition forces, including soldiers who decided to support the rebels. Eastern Libya, centered on the port city of Benghazi, was said to be firmly in the hands of the opposition. Tripoli and its surrounding areas remained disputed. Forces loyal to Gaddafi were able to fight back against rebel advances in Western Libya. They launched a counterattack along the coast toward Benghazi, the main center of the uprising. The town of Zawiya, 48 kilometers (30 miles) from Tripoli, was attacked by Air Force planes and Army tanks. It was then taken by Jamahiriya troops, who used "a level of brutality not yet seen in the conflict."

In several public appearances, Gaddafi threatened to crush the protest movement. Al Jazeera and other news agencies reported that his government was arming pro-Gaddafi militias to kill protesters and people who left the regime in Tripoli. United Nations groups, including United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and the United Nations Human Rights Council, said the crackdown violated international law. The Human Rights Council even expelled Libya, an action urged by Libya's own delegation to the UN. The United States placed economic sanctions against Libya, followed shortly by Australia, Canada, and the United Nations Security Council. The Security Council also voted to send Gaddafi and other government officials to the International Criminal Court for investigation.

On March 17, 2011, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1973 with a 10–0 vote and five countries not voting. The resolution allowed for a no-fly zone and the use of "all means necessary" to protect civilians in Libya.

Shortly afterward, Libyan Foreign Minister Moussa Koussa stated that "Libya has decided an immediate ceasefire and an immediate halt to all military operations."

On March 19, the first Allied action to secure the no-fly zone began. French military jets entered Libyan airspace on a reconnaissance mission, signaling attacks on enemy targets. Allied military action to enforce the ceasefire started the same day when a French aircraft fired and destroyed a vehicle on the ground. French jets also destroyed five tanks belonging to the Gaddafi regime. The United States and United Kingdom launched attacks on over 20 "integrated air defense systems" using more than 110 Tomahawk cruise missiles during operations Odyssey Dawn and Ellamy.

On June 27, 2011, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Gaddafi. They claimed Gaddafi had personally planned and carried out "widespread and systematic attacks against civilians, demonstrators, and dissidents."

By August 22, 2011, rebel fighters had entered Tripoli and occupied Green Square. They renamed it to its original name, Martyrs' Square, to honor those killed during the Italian occupation. Meanwhile, Gaddafi insisted he was still in Libya and would not give up power to the rebels.

On September 16, 2011, the U.N. General Assembly approved a request from the National Transitional Council. They agreed to accept envoys from the country's temporary ruling body as Tripoli's only representatives at the UN. This effectively recognized the National Transitional Council as the legitimate holder of Libya's UN seat.

The National Transitional Council had internal disagreements during its time as Libya's temporary governing authority. It delayed forming a caretaker, or "interim," government several times before the death of Muammar Gaddafi in his hometown of Sirte on October 20, 2011. Mustafa Abdul Jalil led the National Transitional Council and was generally seen as the main leader. Mahmoud Jibril served as the NTC's acting head of government from March 5, 2011, until the end of the war. He announced he would resign after Libya was declared "liberated" from Gaddafi's rule.

The "liberation" of Libya was celebrated on October 23, 2011. Jibril announced that discussions were underway to form an interim government within one month. This would be followed by elections for a constitutional assembly within eight months, and parliamentary and presidential elections within a year after that. He stepped down as expected the same day and was replaced by Ali Tarhouni. At least 30,000 Libyans died in the civil war.

Transition and the Second Civil War

After the First Civil War, the National Transitional Council (NTC) was in charge of managing Libya's transition. Libya's "liberation" was celebrated on October 23, 2011. Then, Jibril announced plans for an interim government within a month, followed by elections for a constitutional assembly within eight months, and parliamentary and presidential elections within a year. He stepped down that day and was replaced by Ali Tarhouni.

On November 24, Tarhouni was replaced by Abdurrahim El-Keib. El-Keib formed a provisional government, filling it with independent or NTC politicians, including women.

After Gaddafi's fall, Libya faced internal struggles. Protests started against the new NTC government. Gaddafi's loyalists rebelled and fought with the new Libyan army.

Because the Constitutional Declaration allowed a multi-party system, political parties like the Democratic Party, Party of Reform and Development, and National Gathering for Freedom, Justice and Development appeared. The Islamist movement also began. To stop it, the NTC government denied power to parties based on religion, tribe, or ethnic groups.

On July 7, 2012, Libyans voted in their first parliamentary elections since Gaddafi's rule ended. More than 100 political parties registered for this election, which formed a temporary 200-member national assembly. This assembly would replace the unelected National Transitional Council, name a prime minister, and form a committee to write a constitution. The vote was delayed several times to fix problems and allow more time for people to register to vote and for candidates to be checked.

On August 8, 2012, the National Transitional Council officially handed power to the fully elected General National Congress. This body was tasked with forming a temporary government and writing a new Libyan Constitution, which would then be approved in a general referendum.

On August 25, 2012, in what seemed to be the "most obvious religious attack" since the civil war ended, unknown attackers used bulldozers to destroy a Sufi mosque with graves in broad daylight in the center of the Libyan capital Tripoli. This was the second such destruction of a Sufi site in two days.

On October 7, 2012, Libya's Prime Minister-elect Mustafa A.G. Abushagur stepped down after failing a second time to get parliamentary approval for a new government. On October 14, 2012, the General National Congress elected former GNC member and human rights lawyer Ali Zeidan as prime minister-designate.

Libyan Constitutional Assembly elections took place in Libya on February 20, 2014. Ali Zidan was removed by the parliament committee and fled from Libya on March 14, 2014. This happened after a rogue oil tanker, the Morning Glory, left the rebel port of Sidra, Libya with Libyan oil that had been taken by the rebels. Ali Zeidan had promised to stop the ship, but failed.

On March 30, 2014, the General National Congress voted to replace itself with a new House of Representatives.

Abdullah al-Thani served as the prime minister temporarily since March 11, 2014. He resigned on April 13, 2014, after he and his family were victims of a "traitorous attack." However, he continued to be prime minister because there was no replacement. Ahmed Maiteeq was elected Prime Minister of Libya in May 2014. But his election happened under disputed conditions. The Libyan Supreme Court ruled on June 9 that Maiteeq's appointment was illegal, and Maiteeq resigned the same day.

As of May 18, 2014, the parliament building was reported to have been stormed by troops loyal to General Khalifa Haftar, reportedly including the Zintan Brigade. The Libyan government described this as an attempted coup.

House of Representatives elections were held in Libya on June 25, 2014.

On July 14, the United States Support Mission in Libya evacuated its staff after 13 people were killed in clashes in Tripoli and Benghazi. The fighting, between government forces and rival militia groups, also forced Tripoli International Airport to close. A militia, including members of the Libya Revolutionaries Operations Room (LROR), tried to take control of the airport from the Zintan militia, which had controlled it since Gaddafi was overthrown. Both militias were believed to be on the official payroll. In addition, Misrata Airport was closed because it depended on Tripoli International Airport for its operations. Government spokesman, Ahmed Lamine, stated that about 90% of the planes at Tripoli International Airport were destroyed or made unusable in the attack. He also said the government might ask for international forces to help restore security.

In December 2015, the Libyan Political Agreement was signed after talks in Skhirat. This was the result of long negotiations between rival political groups in Tripoli, Tobruk, and other places. They agreed to unite as the Government of National Accord (GNA). On March 30, 2016, Fayez Sarraj, the head of the GNA, arrived in Tripoli and began working from there, despite opposition from the GNC.

On April 4, 2019, Khalifa Haftar, the commander of the Libyan National Army, called on his military forces to advance on Tripoli. Tripoli is the capital of the internationally recognized government of Libya. This started the 2019–20 Western Libya campaign. United Nations Secretary General António Guterres and the United Nations Security Council criticized this action.

On October 23, 2020, the 5+5 Joint Libyan Military Commission, representing the Libyan National Army and the GNA, reached a "permanent ceasefire agreement in all areas of Libya." The agreement, effective immediately, required all foreign fighters to leave Libya within three months. A joint police force would patrol disputed areas. The first commercial flight between Tripoli and Benghazi took place that same day. On March 10, 2021, a temporary unity government was formed. It was planned to stay in place until the next Libyan presidential election scheduled for December 10. However, the election has been delayed several times since, meaning the unity government remains in power indefinitely. This has caused tensions that threaten to restart the war.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Libia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Libia para niños

- Arab Spring

- History of North Africa

- History of the Jews in Libya

- List of heads of state of Libya

- Military history of Libya

- Politics of Libya

- Tripoli history and timeline

- Benghazi history and timeline