History of Montreal facts for kids

Montreal is a big city in the province of Quebec, Canada. It was started in 1642. Before Europeans arrived, the area was home to the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, an indigenous people who spoke the Laurentian language. In 1535, Jacques Cartier was the first European to visit the area, exploring the village of Hochelaga on the Island of Montreal. He was looking for a way to Asia. Later, in 1605, Samuel de Champlain tried to set up a fur trading post here, but the Mohawk people, who used the land for hunting, stopped him.

A fort called Ville Marie was built in 1642. It was part of France's plan to create a large French colonial empire. Ville Marie became a key place for the fur trade and for France to expand into New France. But in 1760, the city was given to the British army after the Montreal Campaign. More British people moved to the city, and a local company called the North West Company started a very successful fur trading business.

Montreal officially became a city in 1832. It grew a lot after the Lachine Canal opened, which helped ships travel past difficult rapids. From 1844 to 1849, Montreal was even the capital of the United Province of Canada. By 1860, it was the biggest city in British North America and the main economic and cultural center of Canada. Later, between 1883 and 1918, Montreal grew by adding nearby towns, making it mostly a French-speaking city again. The Great Depression in Canada in the 1930s brought job losses, but things got better by the mid-1930s, and tall buildings (skyscrapers) started to appear.

During World War II, there were protests against forcing people to join the army, leading to the Conscription Crisis of 1944. In the early 1950s, Montreal's population went over one million. A new subway system was built, the harbour was made bigger, and the St. Lawrence Seaway opened. More skyscrapers and museums were also built. Montreal became even more famous around the world when it hosted Expo 67 (a big world's fair) and the 1976 Summer Olympics. A major league baseball team, the Expos, played in Montreal from 1969 to 2004 before moving to Washington, DC. For a long time, English-speaking people controlled business and finance in Montreal. But in the 1970s, as Quebec nationalism grew, many companies moved their main offices to Toronto.

Contents

- Early History of Montreal

- French Colonial Period

- British Rule and the American Revolution

- The City of Montreal Grows

- Montreal in the Early 20th Century (1914–1939)

- Modernizing Montreal and the Quiet Revolution

- Quebec Independence Movement

- Economic Recovery and Growth

- City Mergers and Demergers

- Origin of Montreal's Name

- Images for kids

- See also

Early History of Montreal

The land where Montreal now stands has been home to indigenous peoples for about 8,000 years. The oldest known item found in Montreal is about 4,000 years old. Around 1000 A.D., Iroquoian and other groups around the Great Lakes started growing corn and living in more settled villages. Some settled along the rich St. Lawrence River, where they could fish and hunt. By the 14th century, they had built fortified villages, like the one Jacques Cartier later described.

Historians have studied the people Cartier met and why they disappeared from the valley around 1580. Since the 1950s, studies have shown that these people were the St. Lawrence Iroquoians. They were different from other Iroquoian-speaking groups like the Huron or Iroquois of the Haudenosaunee, but they shared some cultural ways. Their language is called Laurentian.

French Colonial Period

The first European to reach the Montreal area was Jacques Cartier on October 2, 1535. Cartier visited the villages of Hochelaga (on Montreal Island) and Stadacona (near today's Quebec City). He wrote down about 200 words of the people's language.

Seventy years after Cartier, explorer Samuel de Champlain visited Hochelaga, but the village was gone. There were no signs of people living in the valley. Historians have different ideas about why the people left. Some think they moved west or were pushed out by other tribes. Others believe they suffered from diseases brought by Europeans.

Champlain wanted to set up a fur trading post at Place Royal on the Island of Montreal. But the Mohawk people, who mainly lived in what is now New York, successfully defended their hunting grounds. It wasn't until 1639 that the French started a lasting settlement on the Island of Montreal. This was begun by Jérôme le Royer de la Dauversière, a tax collector.

On May 17, 1642, Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, Jeanne Mance, and a few French settlers started a mission called Ville Marie. This was part of a plan by the Roman Catholic Société Notre-Dame de Montréal to create a colony dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In 1644, Jeanne Mance founded the Hôtel-Dieu, which was the first hospital in North America north of Mexico.

Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve was the governor of the colony. In 1648, he gave the first piece of land to Pierre Gadois. In 1650, the Grou family arrived from France and started a land holding. By 1651, Ville-Marie had fewer than 50 people because of repeated attacks by the Mohawk. Maisonneuve went back to France to find 100 more men to save the colony. If he failed, he planned to move everyone to Quebec City. These new settlers arrived on November 16, 1653, and helped Ville Marie survive and grow.

In 1653, Marguerite Bourgeoys arrived to be a teacher. She started Montreal's first school that year and founded the Congrégation de Notre-Dame, which became a teaching group. In 1663, the Sulpician seminary became the new owners of the island. The first water well was dug in 1658 by Jacques Archambault.

Ville Marie became a major center for the fur trade. The town was fortified in 1725. The French and Iroquois Wars threatened Ville-Marie until a peace treaty, known as the Great Peace of Montreal, was signed in Montreal in 1701. After this peace, Montreal and the areas around it could grow without fear of Iroquois attacks.

Even though Quebec was the capital, Montreal was also very important for governing New France. Montreal had a local governor and other officials. For a short time, citizens could elect representatives called syndics to speak for them, but this was stopped because the government worried about political groups forming. Merchants were allowed to form groups called bourses to discuss their concerns.

Montreal's Population Growth

During French rule, the population of Montreal Island included both Indigenous peoples and the French. In 1666, the first count showed 659 French people and about 1000 Indigenous people. This was the only time the Indigenous population was higher than the French on the island. By 1716, the French population had grown to 4,409, while the Indigenous population was 1,177.

French people slowly moved to Montreal. The first settlement in 1642 had 150 people, but many left because of Iroquois attacks. However, migration increased later. Between 1653 and 1659, 200 more people arrived. In total, about 1200 to 1500 migrants settled on Montreal Island between 1642 and 1714. Most of them stayed.

These migrants came from different parts of France. About 65 percent were from rural areas, 25 percent from large cities, and 10 percent from smaller towns. Many were indentured servants, who worked for a period to pay for their travel. Soldiers were another big group of migrants. Many soldiers who came early became important residents of Ville-Marie.

Women also came to the colony, mostly single and looking for husbands. These women usually stayed permanently. For example, 31 girls who arrived in 1653 and 1659 got married within a year. Between 1646 and 1717, 178 French girls were married on Montreal Island. The number of merchants was small because Quebec City was the main place for them.

Montreal's population changed a lot in the 17th century. In 1666, 56 percent of the people were new to Montreal. By 1681, 66 percent of Montrealers were born there. The number of men compared to women also became more balanced over time. By 1715-1730, about 45 percent of the population lived in urban areas.

Montreal's Economy

In the 17th century, Montreal was a key point for moving goods and a stopover for trips into the interior. Because of rapids upriver, large ships could not go past Montreal. Goods had to be carried over land from there. This made Montreal a major distribution center, not just a trading post. Furs and other goods were stored there for trade.

Montreal depended on France for many finished products like iron and salt. Before the late 17th century, finished fabric was Montreal's main import. Local production of wool was limited. Guns, bullets, and powder were also important imports. Blacksmiths were needed to repair guns and make bullets, reducing the need for imports. Other items like kettles, knives, and scissors were imported until local production started around 1660. By 1720, all iron tools could be bought from local blacksmiths.

Soon after Montreal was founded, the Company of One Hundred Associates gave the city's trading rights to local merchants. These merchants formed the "Communaute des Habitants." Both Indigenous peoples and French traders called coureur des bois supplied furs. This company did well until the Iroquois Wars, which caused it to struggle. In 1664, the French West India Company took over the "Communaute des Habitants."

Even with the Iroquois Wars, there was still a lot of trade with Indigenous peoples. For example, while Montreal Island didn't have a large Indigenous population, about 80,000 Indigenous people lived within 800 kilometers of Montreal. These groups would sometimes come to Montreal to trade. Every August, Montreal held an annual fur fair where hundreds of Indigenous people would come to get better prices for furs. They would stay outside town until late September.

Some Indigenous people also lived permanently on the island and in Montreal. Missions were founded for Indigenous peoples in Montreal, like the La Montagne Mission in 1671. The number of Indigenous people in these missions grew in the 18th century. While Indigenous people were important for trade, they were not fully integrated into the city of Montreal itself. Some Indigenous people were also enslaved in Montreal during this period.

Before 1663, there is little information on how Montreal got its food. The town was too small to be a major market for food. Even though farmers came to Montreal to sell goods like eggs and vegetables, it was not a main center for grain. Despite having extra wheat, flour and lard were still imported to feed French soldiers. This unused wheat surplus was a problem for the settlers and the French government.

In the 18th century, Montreal was a hub for illegal fur trade. This meant selling furs to places other than France. Furs were sometimes taken down the Richelieu River to English and Dutch traders. Some estimates suggest that half to two-thirds of all furs from Montreal were traded illegally in the early 1700s.

Montreal's Design and Buildings

The towns built in New France, like Montreal, tried to look like towns in France. At first, with plenty of wood and little stone, Montreal's buildings were mostly made of wood in the French style. Craftsmen used classic French building methods. Indigenous peoples found these methods strange, as they built mostly with natural materials like branches and bark. Montreal's buildings remained wooden until 1664, when King Louis XIV made the colony an official province.

This change brought "king's engineers" to New France and Montreal. They helped plan the city's layout and started building with stone. The Sulpicians, who owned Montreal from 1663, played a big role in the city's early design. They helped plan Montreal's checkerboard street layout in 1671. For example, Father Superior Dollier de Casson and surveyor Bénigne Basset planned Rue Notre Dame to be Montreal's main street in 1672. These designers were not professional architects, so they worked closely with the religious leaders. Casson also designed the Old Sulpician Seminary in 1684, which is the oldest building still standing in Montreal and has North America's oldest gardens.

Because there were few architects, many buildings had simpler designs than those in France. As stonemasons became more skilled and stone was more available, stone buildings became more common. However, fires were still common in Montreal. When more stone was used, cracking became an issue due to cold and heat. This led to a basic building plan that worked for the climate. Roofs in Montreal were steep and covered with cedar shingles or cheaper Canadian-style sheet metal, not slate like in France. The Château Ramezay, built in 1705 for Governor Claude de Ramezay, used these styles.

After fire rules were put in place in 1721, Canadian-specific architecture began to develop. Wood was removed from buildings as much as possible, making them almost entirely stone. This also removed many fancy wooden decorations common in France. So, only churches had much decoration, and many colonial buildings looked plain. Wealthy people showed their importance by building larger buildings, which increased the demand for stone and helped Montreal grow.

Montreal's Military History

In 1645, a fort was built on Montreal Island, marking the start of its military history. This fort was important for stopping Iroquois attacks and became a base for soldiers. After Maisonneuve's return in 1653, Montreal became a key starting point for expeditions into the frontier. However, Montreal was not fully strengthened until New France became a province and "king's engineers" arrived with more soldiers. Many early expeditions to explore Ontario and the Ohio River Valley started in Montreal, but often faced strong Indigenous resistance.

In the early 1700s, many military expeditions left Montreal to deal with hostile Indigenous groups and strengthen ties with Indigenous allies. One of the most important events was the Great Peace of 1701. This conference took place in August between the French and representatives from 39 different Indigenous nations. About 2000-3000 people attended, including around 1300 Indigenous delegates. The French and Indigenous leaders gave speeches and performed peace gestures like burying hatchets and exchanging wampum belts. Indigenous leaders signed the treaty with their totem symbols.

The Great Peace ended the Iroquois Wars and brought peace to a large area. The French hoped to create a military border with their Indigenous allies against the advancing British colonies. So, many forts were built along the borders, from the Ohio Valley to New Orleans. Many of these forts, like Detroit, relied on Montreal for supplies and soldiers, increasing Montreal's military role.

Because Montreal was so important to New France, city walls were built to protect it. These double walls were 6.4 meters tall and over three kilometers long, completed in 1737 after 20 years of building. Only parts of the base of the wall remain today. These walls made Montreal the most militarily strong town in New France. When the Seven Years' War began, Montreal became the military headquarters for operations in North America. This meant more soldiers in Montreal, which put a strain on the city's supplies.

In 1757, there were so many soldiers and Indigenous allies in Montreal that Governor Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil realized they needed to act, or the army and town would run out of food. This led to a major campaign. General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm led a large force out of Montreal, leaving a smaller group behind. Montcalm had success in his military efforts, keeping spirits high in Montreal. After his victory at Carillon, Montcalm returned to Montreal. However, he had fewer troops than the British. Learning of a British invasion coming over the Saint Lawrence, Montcalm took his forces to Quebec City. He died there, and Quebec City was lost. This shocked Montreal, which briefly became the capital, but with three British armies heading its way, the town could not last. In September 1760, the French forces finally gave up to the British, ending French rule in Montreal.

British Rule and the American Revolution

Ville-Marie remained a French settlement until 1760, when it was surrendered to the British army under Jeffery Amherst. After Great Britain won the Seven Years' War, the Treaty of Paris in 1763 officially gave Canada and all its lands to Britain.

As a British colony, people from Britain could now move to Montreal. The city began to grow with British immigrants. During the 1775 invasion of Canada, American Revolutionists led by General Richard Montgomery briefly captured Montreal. But they left when they realized they couldn't hold Canada. Many English-speaking Loyalists who supported Britain moved to Canada from the American colonies during and after the American Revolution. In 1782, Montreal's population was estimated at 6,000.

More and more English-speaking merchants and residents arrived in Montreal in the 19th century. Soon, English became the main language for business in the city. The best time for fur trading began with the local North West Company, which was the main competitor to the British Hudson's Bay Company. By 1821, Montreal had 18,767 residents.

The city's population was mostly French-speaking until the 1830s. From the 1830s to about 1865, most people were English-speaking, many having recently moved from the British Isles. A large fire destroyed a quarter of the town on May 18, 1765.

Scottish Contributions

Scottish immigrants built Montreal's first bridge across the Saint Lawrence River. They also started many of the city's big industries, including Henry Morgan's department store (Morgan's), the Bank of Montreal, Redpath Sugar, and both of Canada's national railroads. The city grew quickly as railways were built to New England, Toronto, and the west. Factories were set up along the Lachine Canal. Many buildings from this time are still in the area known as Old Montreal. Scots were also known for their charity work. They founded and funded many Montreal institutions, such as McGill University and the Royal Victoria Hospital.

The City of Montreal Grows

Montreal became an official city in 1832. Its growth was boosted by the opening of the Lachine Canal. This canal allowed ships to bypass the difficult Lachine Rapids south of the island. As the capital of the United Province of Canada from 1844 to 1849, Montreal attracted more English-speaking immigrants, including Irish, Scottish, and English people. Montreal's population grew from 40,000 in 1841 to 57,000 ten years later.

Riots led by a group called the Tories resulted in the burning of the Provincial Parliament. Instead of rebuilding, the government chose Toronto as the new capital. In Montreal, the English-speaking community continued to build McGill, one of Canada's first universities. Wealthy people built large mansions at the foot of Mount Royal as the suburbs expanded.

American Civil War Connection

Montreal was a major port with direct links to Britain and France, making it important during the American Civil War. Confederate troops got weapons and supplies from the British here. Union soldiers and agents spied on them and arranged for weapons from France. John Wilkes Booth, who later assassinated President Lincoln, spent time in Montreal. After the war, Confederate President Jefferson Davis stayed in a manor house in Montreal.

Industrial Growth

The Lachine Canal and new businesses connected Montreal's port with markets across the continent. This led to rapid industrialization in the mid-19th century. The economic boom attracted French-Canadian workers from the countryside to factories in nearby towns like Saint-Henri and Maisonneuve. Irish immigrants settled in working-class areas like Pointe-Saint-Charles. This made the English and French language groups almost equal in size. The growing city also attracted immigrants from Italy and Eastern Europe.

In 1852, Montreal had 58,000 people. By 1860, it was the largest city in British North America and the main economic and cultural center of Canada. From 1861 until the Great Depression of 1930, Montreal had what some historians call its Golden Age. Saint Jacques Street became the most important economic center in Canada. The Canadian Pacific Railway set up its main office there in 1880, and the Canadian National Railway in 1919. When it was built in 1928, the new head office of the Royal Bank of Canada was the tallest building in the British Empire.

By adding neighboring towns between 1883 and 1918, Montreal became a mostly French-speaking city again. The tradition of having alternating French-speaking and English-speaking mayors began, lasting until 1914. Montreal and Toronto shared control of the Canadian stock market from the 1850s to the 1970s, creating a rivalry between them.

Montreal in the Early 20th Century (1914–1939)

Many Montrealers volunteered for the army at the start of World War I. However, most French Montrealers were against mandatory conscription (forcing people to join the army), and enlistment numbers dropped.

Montreal's population was 618,000 in 1921 and grew to 903,000 by 1941. The 1920s brought many changes and new technologies. Cars started to change the city. The world's first commercial radio station began broadcasting in 1920. Montreal also became the eastern hub for Trans-Canada Airway in 1939.

Film production also grew in the city. The National Film Board of Canada was created in Montreal in 1939, making many documentary films during World War II. Other cultural developments included the founding of Université de Montréal in 1919 and the Montreal Symphony Orchestra in 1934. The Montreal Forum, built in 1924, became the home of the famous Montreal Canadiens hockey team.

Dr. Wilder Penfield founded the Montreal Neurological Institute in 1934 to study and treat brain diseases. During World War II, research for nuclear weapons was done at the Montreal Laboratory.

The Great Depression's Impact

During the Great Depression in Canada in the 1930s, many people in Montreal were unemployed. Canada started to recover in the mid-1930s, and real estate developers began building skyscrapers, changing Montreal's skyline. The Sun Life Building, built in 1931, was for a time the tallest building in the British Commonwealth. During World War II, its vaults were used to hide the gold bullion of the Bank of England and the British Crown Jewels.

With so many men out of work, women had to be very careful with money to manage the family budget. About a quarter of the workforce were women, but most women were homemakers. They used cheap foods like soups, beans, and noodles. They bought the cheapest cuts of meat and reused leftovers. They sewed and patched clothes, traded with neighbors, and kept their homes colder. New furniture and appliances were put off until better times. These strategies show that women's work at home was very important for the family's finances. Many women also worked outside the home or did odd jobs for money or trade. Families helped each other with food, rooms, and loans.

World War II in Montreal

Canada declared war on Germany in September 1939, which led to an economic boom that ended the Depression. Mayor Camillien Houde protested against conscription. He told Montrealers to ignore the federal government's registration of all men and women, believing it would lead to conscription. The federal government in Ottawa saw Houde's actions as treason and put him in a prison camp from 1940 to 1944. That year, the government did bring in conscription to expand the armed forces (see Conscription Crisis of 1944).

Modernizing Montreal and the Quiet Revolution

By the early 1960s, a new political movement called the Quiet Revolution was growing in Quebec. The new Liberal government led by Jean Lesage made changes that helped French-speaking Quebecers gain more power in politics and the economy. Montreal became the center of French culture in North America. More French-speaking people started owning businesses.

From 1962 to 1964, four of Montreal's ten tallest buildings were completed: Tour de la Bourse, Place Ville-Marie, the CIBC Building and CIL House. Montreal gained more international fame because of Expo 67, a World's Fair held in 1967. Innovative buildings like Habitat were built for it. During the 1960s, Mayor Jean Drapeau improved the city's infrastructure, building the Montreal Metro (subway) system. The provincial government also built much of today's highway system.

In 1969, a police strike led to 16 hours of unrest known as the Murray Hill riot. Police went on strike because of difficult working conditions and a desire for higher pay. The National Assembly of Quebec passed an emergency law forcing the police back to work.

The 1976 Summer Olympics were held in Montreal, making it the first Olympics in Canada. The Games helped introduce Quebec and Canada to the world. The whole province prepared for the games, leading to a new interest in sports. However, the city went $1 billion into debt because of the Games.

Quebec Independence Movement

In the late 1960s, the movement for Quebec's independence was strong due to disagreements between the Ottawa (federal) and Quebec governments. Radical groups formed, like the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ). In October 1970, FLQ members kidnapped and murdered Pierre Laporte, a minister, and also kidnapped James Cross, a British diplomat (who was later released). The Prime Minister of Canada, Pierre Trudeau, sent the military to Montreal and used the War Measures Act, giving police special powers. These events became known as the October Crisis of 1970.

The question of Quebec's independence was put to a vote. The Parti Québécois held two referendums on the issue, in 1980 and 1995. During these decades, about 300,000 English-speaking Quebecers left Quebec. The uncertain political situation caused many Montrealers, mostly English-speaking, to move their businesses and families to other provinces.

With the Bill 101 passed in 1977, French became the only official language for all levels of government in Quebec. It also became the main language for business, culture, and public signs. In the rest of Canada, the government adopted a policy of using both French and English. The success of the separatist Parti Québécois caused uncertainty about Quebec's economic future, leading many company headquarters to move to Toronto and Calgary.

In recent years, the idea of Quebec independence has seen a rise in popularity. The Bloc Québécois, a leading Quebec separatist party, gained more votes in the 2019 election.

Economic Recovery and Growth

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Montreal's economic growth was slower than other major Canadian cities. However, by the late 1990s, Montreal's economy improved. New companies and organizations started to fill the city's business and financial roles.

As the city celebrated its 350th anniversary in 1992, construction began on two new skyscrapers: 1000 de La Gauchetière and 1250 René-Lévesque. Montreal's improving economy allowed for more upgrades to the city's infrastructure. The subway system was expanded, new skyscrapers were built, and new highways were developed, including the start of a ring road around the island.

Montreal attracted several international organizations to its Quartier International (International Quarter). These included the International Air Transport Association (IATA) and the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). With new developments like the Centre de Commerce Mondial (World Trade Centre), Montreal is regaining its international position as a world-class city.

City Mergers and Demergers

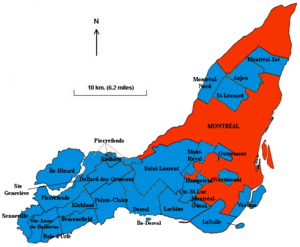

The idea of having one city government for the entire Island of Montreal was first suggested in the 1960s. Many suburbs were against this idea. However, some areas like Rivière-des-Prairies and Ville Saint Michel were added to Montreal between 1963 and 1968. Pointe-aux-Trembles was added in 1982.

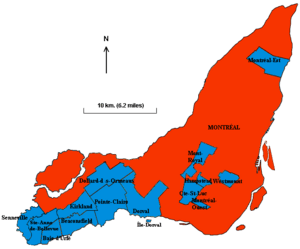

In 2001, the provincial government announced a plan to merge major cities with their suburbs. On January 1, 2002, the entire Island of Montreal, with 1.8 million people, was merged into a new "megacity." About 27 suburbs and the former city of Montreal were combined into several boroughs, named after their old cities or districts.

During the 2003 provincial elections, the winning Liberal Party promised to hold votes on the mergers. On June 20, 2004, many of the former cities voted to separate from Montreal and become independent again. These included Baie-d'Urfé, Beaconsfield, Côte Saint-Luc, Dollard-des-Ormeaux, Dorval, L'Île-Dorval, Hampstead, Kirkland, Montréal-Est, Montreal West, Mount Royal, Pointe-Claire, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Senneville, and Westmount. These separations became official on January 1, 2006.

Some areas like Anjou, LaSalle, and Saint-Laurent had majority votes to separate, but not enough people voted for the decision to be valid. So, these former municipalities remained part of Montreal. No vote was held in areas like Lachine, Montréal-Nord, or Verdun.

The Island of Montreal now has 16 municipalities: the city of Montreal itself and 15 independent cities. The city of Montreal, with its current borders (divided into 19 boroughs), covers about 366 square kilometers and has a population of 1,583,590 people (based on 2001 numbers). This is a big increase in both land area and population compared to the old city of Montreal.

The 15 independent cities that separated have fewer government powers than they did before the merger. A joint board that covers the entire Island of Montreal, where the city of Montreal has more power, keeps many responsibilities.

Even after the votes in 2004, there is still debate about the cost of separating. Some studies suggest that the independent cities will face high financial costs, possibly needing to raise taxes. However, those who supported the separations disagree with these studies. They point to reports from other merged cities that show that large "mega-municipalities" can be more expensive than expected.

Origin of Montreal's Name

In the early 18th century, the name of the island started to be used for the town. Two maps from 1744 called the island "Isle de Montréal" and the town "Ville-Marie." But a 1726 map referred to the town as "la ville de Montréal." The name Ville-Marie soon stopped being used for the city. Today, it refers to a borough of Montreal that includes downtown.

In the modern Mohawk language, Montreal is called Tiohtià:ke. In Algonquin, it is called Moniang.

Images for kids

-

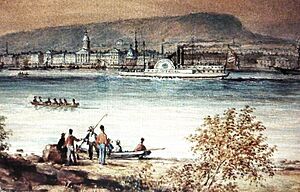

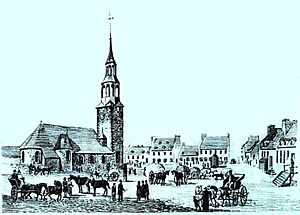

Depiction of the Bonsecours Market and Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours Chapel in Montreal, 1853.

-

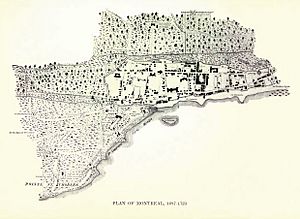

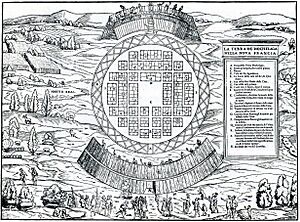

Map of Hochelaga in 1535. Hochelaga was the first indigenous settlement in Montreal to make contact with Europeans.

-

Jacques Cartier at Hochelaga. Cartier was the first European to arrive in the area, arriving in 1535.

-

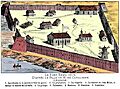

Depiction of the first church in Fort Ville-Marie in the 1640s. The settlement was established in 1642 under the authority of Société Notre-Dame de Montréal.

-

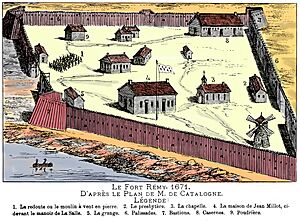

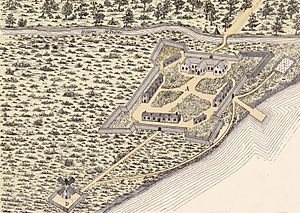

Fort Remy in 1671. An outpost erected west of Ville-Marie, the town saw its fortification as the war with the Iroquois threatened its survival.

-

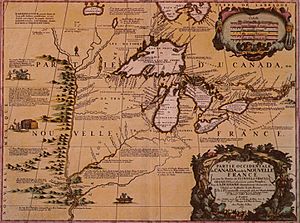

Map of the Great Lakes area west of Montreal. Because of rapids west of Montreal, portages were required to travel further inland, making Montreal a key distribution point for trade.

-

Depiction of the fur trade in 1662. The fur trade with the natives and the coureur des bois was a vital part of the settlement's early economy.

-

Saint-Sulpice Seminary in 1839. Completed in 1687, the seminary is the oldest standing building in Montreal.

-

Depiction of Fort Ville-Marie in 1645. Fort Ville-Marie was the first European fortified settlement established the area.

-

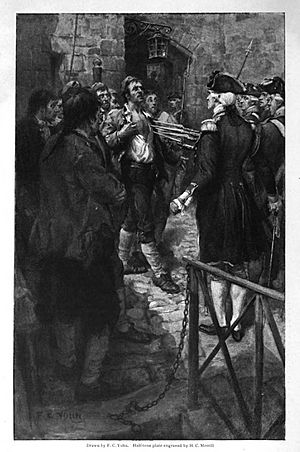

Ethan Allen marched through the streets of Montreal after his attempt to take the city in 1775. A few months later, the city would be briefly occupied by American rebels.

-

View of Lachine Canal in 1852. Bypassing the rapids west of the city, the canal linked Montreal with other continental markets, spurring its industrialization.

-

An anti-conscription rally in Montreal, 1917. French-Canadian opposition towards conscription in the latter years of World War I led to the Conscription Crisis of 1917.

-

A Montreal soup kitchen in 1931. Like the rest of Canada, unemployment in Montreal was high during the Great Depression.

-

Lighting of the Olympic Torch inside Montreal's Olympic Stadium. The city hosted the 1976 Summer Olympics.

-

The municipalities of the Island of Montreal prior to the 2002 merger of all municipalities on the island.

See also

- History of Quebec

- List of historic places in Montreal

- List of National Historic Sites of Canada in Montreal

- Timeline of Montreal history

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |