History of Quebec facts for kids

Quebec was first called Canada between 1534 and 1763. It was the most important colony of New France. It was also the center of New France, overseeing other areas like Acadia and Louisiana. Key parts of Quebec's early history include the fur trade, exploring North America, wars against the English, and making alliances or fighting with Native American groups.

After the Seven Years' War, Quebec became a British colony. It was known by different names: the Province of Quebec (1763–1791), then Lower Canada (1791–1841), and then Canada East (1841–1867). During this time, French-speaking people often had less power because English speakers controlled many businesses. The Catholic church was very important. People resisted losing their French culture and felt separated from non-English speaking groups.

Quebec joined with Ontario, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick in 1867. This started the country of Canada. Important events from this time include the World Wars, a period called the Grande Noirceur, and the Quiet Revolution. The Quiet Revolution helped French Canadians gain more power and made Quebec less controlled by the church. It also led to the start of the modern Quebec sovereignty movement.

These three main periods of Quebec's history are shown on its coat of arms. It has three fleur-de-lis (for the French period), a lion (for the British period), and three maple leaves (for the Canadian period).

Contents

- Quebec's Changing Names

- Early People of Quebec

- European Explorers Arrive

- New France (1608–1763)

- Province of Quebec (1763–1791)

- Lower Canada (1791–1840)

- Province of Canada (1840-1867)

- Confederation and Early Quebec (1867–1914)

- Early 20th Century Quebec (1915-1959)

- Late 20th Century Quebec (1960-1999)

- 21st Century Quebec (2000-Present)

Quebec's Changing Names

Here are the different names Quebec has had over time. Names in bold are for provinces or larger areas.

- Canada, the main part of New France (1608–1761): A French colony.

- Province of Quebec (1763–1791): A British colony.

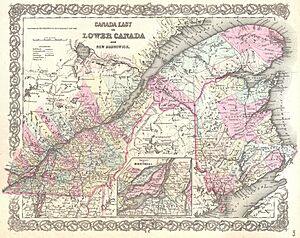

- Lower Canada, part of the Canadas (1791–1841): A British colony.

- The Canada East part of the Province of Canada (1841–1867): A British colony.

- Quebec (1867–present): A province of Canada.

Early People of Quebec

The first people to live in Quebec were the Paleo-Indians. Scientists believe they came from Asia to America between 20,000 and 14,000 years ago. They arrived in Quebec after the large ice sheets melted, about 11,000 to 10,000 years ago. Many different groups of people developed from them over time. Most of their stories are now lost because they did not have a written language. Before Europeans arrived, these groups shared their history and knowledge through oral tradition, by telling stories.

Paleo-Indian Era (11,000–8000 BC)

Old tools and other items found by archaeologists show that people lived in Quebec around 10,000 BC.

Archaic Era (8000–1500 BC)

After the Paleo-Indian period came the Archaic era. During this time, Quebec's land changed a lot as the ice fully melted. More land became livable. The environment, including climate, plants, lakes, and rivers, became more stable. People moved around less often. Moving was mostly a seasonal activity for hunting, fishing, or gathering food.

The people of the Archaic period were nomadic, meaning they moved from place to place. But they were more settled than before. They knew a lot about the resources in their areas. They learned to adapt to their surroundings and their population grew. Their food and tools became more varied. They used more local materials and developed new skills, like polishing stone. They also made specialized tools, such as knives, fish hooks, and nets.

Woodland Era (3000 BC–1500 AD)

Farming started to appear around 800 BC. By the 14th century, people in the Saint Lawrence River valley, called Iroquoians, were skilled farmers. They grew corn, squash, sunflowers, and beans.

By the 1500s, Inuit communities lived in Nunavik. There were also 11 First Nations groups:

Each of these groups had their own languages, ways of life, economies, and religious beliefs. Some experts also believe the St. Lawrence Iroquoians were a separate group.

European Explorers Arrive

In the 14th century, the Byzantine Empire fell. This made it harder for Christian countries in the West to trade with the Far East for things like spices and gold. Sea routes were now controlled by Arab and Italian merchants who were less cooperative. So, in the 15th and 16th centuries, Spanish and Portuguese explorers, then English and French, began looking for new sea routes.

In 1508, just 16 years after Christopher Columbus's first trip, Thomas Auber brought some Native Americans back to France. He was likely on a fishing trip near Newfoundland. This shows that French sailors were exploring the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the early 1500s, along with Basque and Spanish sailors.

Around 1522–1523, an Italian sailor named Giovanni da Verrazzano convinced King Francis I of France to send him on a trip. The goal was to find a western route to China. So, in 1524, King Francis I sent Verrazzano to search for the Northwest Passage. This trip was not successful, but it gave the name "New France" to Northeastern North America.

On June 24, 1534, French explorer Jacques Cartier placed a cross on the Gaspé Peninsula. He claimed the land for King François I of France.

On his second trip on May 26, 1535, Cartier sailed up the river. He reached the St. Lawrence Iroquoian villages of Stadacona (near today's Quebec City) and Hochelaga (near today's Montreal). That year, Cartier named the village and nearby lands Canada. He heard two young natives use the word kanata, which meant "village" in their Iroquois language. European mapmakers quickly started using this name. Cartier also thought he found lots of diamonds and gold, but it was only quartz and pyrite. He then followed what he called the Great River (the St Lawrence River) west to the Lachine Rapids. The water was too dangerous for him to continue towards China. Cartier and his sailors had to return to Stadacona and stay there for the winter. In the end, Cartier went back to France. He took about 10 Native Americans with him, including the chief, Donnacona. In 1540, Donnacona told the King of France the legend of the Kingdom of Saguenay. This made the king order a third trip, led by Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval, to find this kingdom. But it was not successful.

In 1541, Jean-François Roberval became the leader of New France. He was in charge of building a new colony in America. Cartier built the first French settlement in America, called Charlesbourg Royal.

France was disappointed after Cartier's three trips. They did not want to spend more money on such uncertain adventures. For a while, French leaders lost interest in the new world. Only at the very end of the 16th century did their interest in these northern lands return.

Even when France did not send official explorers, Breton and Basque fishermen came to the new lands. They came to get cod fish and whale oil. Since they had to stay for a longer time, they started trading metal objects for furs from the Indigenous people. This trade became profitable. This made France interested in the territory again.

The fur trade made it worthwhile to live in the country permanently. Good relationships with the Indigenous people who provided furs were important. Some fishermen only stayed for the season. Companies were formed that tried to get the King to support colonizing the land. They asked France to give one company a monopoly, meaning only they could trade. In return, this company would also take on the job of colonizing the French American land. This way, it would not cost the king much money to build the colony. However, other merchants wanted trade to remain open to everyone. This disagreement was a big issue around 1600.

By the end of the 17th century, a count showed that about 10,000 French settlers were farming along the lower St. Lawrence Valley. By 1700, fewer than 20,000 people of French origin lived in New France. This area stretched from Newfoundland to the Mississippi River. Most Quebec settlers were farmers.

Around 1580, France became interested in America again because the fur trade became important in Europe. France returned to America looking for beavers. New France had many beavers. It became a trading post where the main activity was the fur trade in the Pays-d'en-Haut (the "Upper Country"). In 1600, Pierre de Chauvin de Tonnetuit started the first permanent trading post in Tadoussac. This was for trips into the Domaine du Roy (the King's Domain).

In 1603, Samuel de Champlain traveled to the Saint Lawrence River. At Pointe Saint-Mathieu, he made a defense agreement with the Innu, Wolastoqiyik, and Micmacs. This agreement was very important for France to keep its colony in America, even though the British had many more settlers in the South. This also started French military support for the Algonquian and Huron peoples. They needed help defending against Iroquois attacks. These Iroquois attacks became known as the Beaver Wars. They lasted from the early 1600s to the early 1700s.

New France (1608–1763)

Modern Quebec was part of New France. This was the general name for France's North American lands until 1763. At its largest, before the Treaty of Utrecht, New France included several colonies. Each had its own government: Canada, Acadia, Hudson Bay, and Louisiana.

The exact borders of these colonies were not clear. They were open on the western side, as old maps show.

Early Years (1608–1663)

Quebec City was founded in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain. Other towns were founded before, like Tadoussac in 1604, which still exists. But Quebec was the first meant to be a permanent settlement, not just a trading post. Over time, it became a main part of Canada and all of New France.

The first version of the town was a large walled building called the Habitation. A similar Habitation was built in Port Royal in Acadia in 1605. This was for protection against perceived threats from Indigenous people. It was hard to get supplies to Quebec City from France. Also, people did not know the area well, so life was difficult. Many people died from hunger and diseases during the first winter. However, farming soon grew. A steady stream of immigrants, mostly men looking for adventure, increased the population.

The settlement was built as a permanent fur trading post. First Nations people traded their furs for French goods. These included metal objects, guns, alcohol, and clothing. In 1616, the Habitation du Québec became the first permanent French settlement. This was with the arrival of its first two settlers: Louis Hébert and Marie Rollet.

The French quickly set up trading posts across their land. They traded for fur with Indigenous hunters. Coureur des bois, who were independent traders, explored much of the area themselves. They kept trade and communication flowing through a large network along the rivers. They built fur trading forts on the Great Lakes, Hudson Bay, Ohio River, and Mississippi River. This network was later used by English and Scottish traders after France lost Quebec. Many coureur des bois became voyageurs for the British.

In 1612, the Compagnie de Rouen was given the royal order to manage New France and the fur trade. In 1621, the Compagnie de Montmorency replaced them. Then, in 1627, the Compagnie des Cent-Associés took over. This company brought French laws and the seigneurial system to New France. They also said that only Roman Catholics could settle in New France. The Catholic Church was given large and valuable pieces of land. This was about 30% of all the land given by the French King in New France.

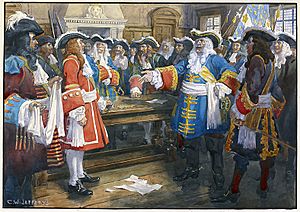

Because of war with England, the first two groups of ships and settlers for the colony were stopped. British privateers, led by the Kirke brothers, stopped them near Gaspé. Quebec was cut off. In 1629, Quebec surrendered without a fight to the English privateers led by David Kirke. Champlain and other colonists were taken to England. There, they learned that peace had been agreed upon before Quebec's surrender. The Kirkes were supposed to return what they took. However, they refused. It was not until the 1632 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye that Quebec and all other captured French lands in North America were returned to New France. Champlain became governor again but died three years later.

In 1633, Cardinal Richelieu gave a charter to the Company of One Hundred Associates. This company controlled the fur trade and land rights. In return, they were supposed to support and expand settlement in New France. This included Acadia, Quebec, Newfoundland, and Louisiana. The charter said they had to bring 4000 settlers to New France over 15 years. But the company mostly ignored this and focused on the fur trade. Only 300 settlers arrived before 1640. The company went almost bankrupt. It lost its fur trade monopoly in 1641 and was finally closed in 1662.

In 1634, Sieur de Laviolette founded Trois-Rivières. In 1642, Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve founded Ville-Marie (now Montreal). He chose an island for Montreal so it would be naturally protected from Iroquois attacks. Many heroes of New France came from this time, like Dollard des Ormeaux and Madeleine de Verchères.

Royal Province (1663–1760)

In 1663, the Company of New France gave Canada to King Louis XIV. He officially made New France a royal province of France. New France became a true colony managed by the Sovereign Council of New France from Quebec City. It used a system of triangular trade. A governor-general, helped by the intendant of New France and the bishop of Québec, would rule the colony of Canada. This included Montreal, Québec, Trois-Rivières, and the Pays-d'en-Haut. It also included its other areas: Acadia, Louisiana, and Plaisance.

The French settlers were mostly farmers. They were known as "Canadiens" or "Habitants". Not many new people immigrated, but the colony still grew because the Habitants had many children. In 1665, the Carignan-Salières regiment built forts to protect against Iroquois attacks. The Regiment brought 1,200 new men from France. To fix the problem of too many single men and not enough women, King Louis XIV paid for about 800 young French women, called les filles du roi, to come to the colony. In 1666, intendant Jean Talon took the first count of the colony. He counted 3,215 Habitants. Talon also made rules to grow different kinds of crops and encourage births. By 1672, the population had grown to 6,700 Canadiens.

In 1686, the Chevalier de Troyes and the Troupes de la Marine took three northern forts. The English had built these forts near Hudson Bay. Similarly, in the south, Cavelier de La Salle claimed lands for France. These lands were discovered by Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet in 1673 along the Mississippi River. As a result, New France grew to stretch from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico. It also included the Great Lakes.

In the early 1700s, Governor Callières made the Great Peace of Montreal. This agreement confirmed the alliance between the Algonquian peoples and New France. It also ended the Beaver Wars. In 1701, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville founded the area of Louisiana. Its main office was in Biloxi, Mississippi, then Mobile, Alabama, and later New Orleans. At this time, the town had 2,000 settlers. In 1738, Pierre Gaultier de Varennes expanded New France to Lake Winnipeg. In 1742, his sons, François and Louis-Joseph, crossed the Great Plains and found the Rocky Mountains.

From 1688 onwards, France and Britain fought fiercely to control North America. They wanted to control the fur trade. This led to New France and its Indigenous allies fighting against the Iroquois and the English. These were a series of four wars called the French and Indian Wars by Americans, and the Intercolonial wars in Quebec. The first three wars were King William's War (1688–1697), Queen Anne's War (1702–1713), and King George's War (1744–1748). Many important battles and land changes happened. In 1690, the Battle of Quebec was the first time Quebec's defenses were tested. In 1713, after the Peace of Utrecht, France gave Acadia and Plaisance Bay to Great Britain. But France kept Île Saint-Jean and Île-Royale (Cape Breton Island), where the Fortress of Louisbourg was later built. These losses were important because Plaisance Bay was the main way to communicate between New France and France. Acadia had 5,000 Acadians. In the siege of Louisbourg in 1745, the British won. But they gave the city back to France after war agreements.

Catholic Nuns

Outside the home, women in Canada had few areas they controlled. An important exception was Roman Catholic nuns. New groups for women started in the 17th century and became a lasting part of Quebec society.

The Ursuline Sisters arrived in Quebec City in 1639 and in Montreal in 1641. They also spread to smaller towns. They faced hard conditions, unsure money, and unhelpful leaders. They worked in education and nursing. They received donations and became important landowners in Quebec. Marie de l'Incarnation (1599–1672) was the mother superior in Quebec from 1639–1672.

During the 1759 Quebec Campaign of the Seven Years' War, a nun named Marie-Joseph Legardeur de Repentigny managed the Hôpital Général in Quebec City. She oversaw the care of hundreds of wounded soldiers from both French and British armies. She wrote a report saying, "The surrender of Quebec only increased our work." The British generals promised them protection and made them responsible for their sick and wounded. British officers at the hospital reported that the care was clean and high quality. Most civilians left the city. The Hôpital Général became a place for poor refugees. The nuns set up a mobile aid station. They reached out to refugees, giving out food and treating the sick and injured.

British Conquest of New France (1754–1763)

In the mid-18th century, British North America had grown large, with over 1 million people. It was almost an independent country. Meanwhile, New France was still seen mostly as a cheap source of natural resources for France. It had only 60,000 people. New France was larger in land area than the Thirteen Colonies, but its population was less than one-tenth the size. There was fighting along the borders. The French supported Indian raids into the American colonies.

The first battles of the French and Indian War happened in 1754. Soon, this war grew into the worldwide Seven Years' War. New France at that time included parts of what is now Upstate New York. Several battles were fought there. The French military had early successes in these border battles. They gained control over several important places in 1756 and 1757.

The British sent many soldiers. The Royal Navy controlled the Atlantic Ocean, stopping France from sending much help. In 1758, the British captured Louisbourg. This gave them control over the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. They also took control of key forts in battles at Frontenac and Duquesne. Even with a big defeat of the British in the Battle of Carillon, the French military was in a bad position.

In 1759, the British aimed directly at the heart of New France. General James Wolfe led a fleet of 49 ships with 8,640 British troops to Quebec fortress. They landed on Île d'Orléans and on the south side of the river. The French forces, led by Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, held the walled city and the north side. Wolfe besieged the city for over two months, exchanging cannon fire. But neither side could break the siege. Since neither side could get more supplies during winter, Wolfe decided to force a battle. On September 5, 1759, the British troops crossed near Cap-Rouge, west of the city. They climbed the steep Cape Diamond without being seen. Montcalm, for reasons still debated, did not use the city walls for protection. He fought on open ground in what became known as the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. The battle was short and bloody. Both leaders died, but the British easily won.

Now that the British had the main city and capital, they slowly took control of the land. The French had a small victory in the Battle of Sainte-Foy outside Quebec in 1760. But an attempt to besiege the city ended in defeat the next month. British ships arrived and forced the French to retreat. An attempt to resupply the French military failed in the naval Battle of Restigouche. Pierre de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnial, New France's last Royal governor, surrendered Montreal on September 8, 1760. The Seven Years' War was still happening in Europe. So, the British put the region under a military government between 1760 and 1763.

Britain's success in the war forced France to give all of Canada to the British in the Treaty of Paris. The Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763, by King George III of Great Britain set the rules for governing the new land. It also defined the area's borders.

This break from France changed the French Canadians. It led to the birth of a new group of people. Their culture would be based on their history in North America. A British official, Lord Durham, later described the relationship between the "Two Solitudes" of Canada. He said, "I found two nations at war within one state." He meant a fight between different groups, not just ideas. New British immigrants saw the American lands as a place to settle and make money. But the Canadiens saw Quebec as their heritage. They saw it as a country already settled, not just a place to colonize.

Province of Quebec (1763–1791)

British rule under Governor James Murray was fair. French Canadians kept their traditional rights and customs. The British Royal Proclamation of 1763 combined three Quebec areas into the Province of Quebec. The British were the first to use the name "Quebec" for a larger area beyond Quebec City. The British allowed the Catholic Church to continue. They protected Quebec's traditional social and economic ways. Much of French law was kept within a system of British courts. All of this was under the British governor. The goal was to keep the French-speaking settlers happy, even though British merchants were annoyed.

Quebec Act (1774)

Trouble was growing in the colonies to the south. This would later lead to the American Revolution. The British worried that the Canadiens might support this rebellion too. At the time, Canadiens made up most of the population of the Province of Quebec. To ensure the Canadiens' loyalty to the British crown, Governor James Murray and later Governor Guy Carleton said that changes were needed. This led to the Quebec Act of 1774. This Act of the British Parliament set rules for governing the Province of Quebec. It brought back French civil law for private matters. But it kept English common law for public administration, including criminal cases. It changed the oath of loyalty so it no longer mentioned the Protestant faith. It also guaranteed the free practice of the Catholic faith. The goal of this Act was to secure the loyalty of French Canadians.

American Revolutionary War

When the American Revolutionary War started in early 1775, Quebec became a target for American forces. They wanted to free the French people there from British rule. In September 1775, the Continental Army began an invasion from two directions. One army captured Montreal. Another traveled through the wild lands of what is now Maine towards Quebec City. The two armies joined forces. But they were defeated in the Battle of Quebec. The American General Richard Montgomery was killed. The Americans were pushed back into New York. This happened when a large army of British troops and German soldiers arrived in June 1776.

Before and during the American occupation, there was a big propaganda war. Both Americans and British tried to get the people's support. The Americans managed to raise two regiments in Quebec. These were led by James Livingston and Moses Hazen. One of these regiments fought throughout the war. Hazen's 2nd Canadian Regiment fought in the Philadelphia campaign and at the Siege of Yorktown. It included many Quebecers.

After General John Burgoyne's failed 1777 campaign to control the Hudson River, Quebec was used as a base. From there, raids were made into the northern United States until the war ended. In the western part of the war, U.S. forces had better success in areas north of the Ohio River. These areas had been added to Quebec in 1774. During the Illinois campaign, Virginia militia leader George Rogers Clark captured Kaskaskia without any losses. From there, his men marched into and captured Vincennes. But it was soon lost to British Lieutenant Colonel Henry Hamilton. It was later taken back by Clark in the Siege of Fort Vincennes in February 1779. About half of Clark's soldiers in that area were French Canadian volunteers who supported the American cause.

When the war ended in 1783, Quebec became smaller. Parts of its southwest were given to the new United States. This was part of the Treaty of Paris. About 75,000 Loyalists, who were loyal to England, left the new United States. Many settled in southern Quebec. These settlers eventually wanted to be separate from the French-speaking Quebec population. This happened in 1791.

Lower Canada (1791–1840)

The Constitutional Act of 1791 divided Quebec into Upper Canada (now part of Ontario) and Lower Canada (now southern Quebec). New English-speaking Loyalist refugees did not want to use Quebec's land system or French civil law. So, the British decided to separate the English-speaking settlements from the French-speaking areas. Upper Canada's first capital was Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake). In 1796, it moved to York (now Toronto).

The new constitution, made mainly for the Loyalists, created a unique situation in Lower Canada. The Legislative Assembly, which was elected, often disagreed with the Legislative and Executive branches, which were appointed by the governor. In the early 1800s, the Parti canadien became a nationalist and reformist party. A long political struggle began between the elected representatives of Lower Canada and the colonial government. Most of the elected representatives were French-speaking professionals like lawyers and doctors.

By 1809, the government of Newfoundland no longer wanted to oversee the coasts of Labrador. To fix this, the British government gave the coasts of Labrador to the colony of Newfoundland. The inland border between Lower Canada and Newfoundland was not clearly defined.

In 1813, Charles-Michel de Salaberry became a hero. He led Canadian troops to victory at the Battle of Chateauguay during the War of 1812. In this battle, 300 Canadian soldiers and 22 Native Americans successfully pushed back 7,000 Americans. This loss made the Americans give up their plan to conquer Canada by taking the Saint Lawrence.

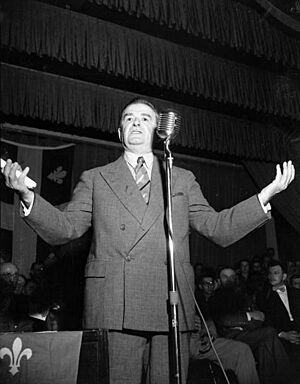

The Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada, which represented the people, argued more and more with the British Crown and its appointed officials. In 1834, things reached a breaking point. The Parti canadien presented its 92 resolutions. These were political demands that showed a real loss of trust in the British monarchy. London refused to consider these. Instead, they sent their own 10 resolutions. Unhappiness grew during public meetings in 1837. These were sometimes led by speakers like Louis-Joseph Papineau. Despite opposition from church leaders, the Rebellion of the Patriotes began in 1837.

Key goals for the rebels were to have a responsible government. For many, they wanted to end the unfair control of the English minority over the French majority. Louis-Joseph Papineau was a key leader for the rebels. The 1837 rebellion led to martial law, meaning the military took control. Canada's Constitution was also suspended. To put power back with the Crown, Lord Durham was named governor of all British North America.

In 1837, Louis-Joseph Papineau and Robert Nelson led people in Lower Canada to form an armed group called the Patriotes. They wanted to end the British governors' control. They made a Declaration of Independence in 1838. It promised human rights and equality for all citizens. Their actions led to rebellions in both Lower and Upper Canada. The Patriotes won their first battle, the Battle of Saint-Denis, because government forces were not ready. However, the Patriotes were not well organized or equipped. They lost their second battle, the Battle of Saint-Charles, and their final battle, the Battle of Saint-Eustache. After the government defeated the Patriotes, the Catholic clergy regained their influence. They encouraged the people to unite and develop the nation in education, health, and society.

Martial Law and Special Council (1838–1840)

The second rebellion in 1838 had bigger consequences. In 1838, Lord Durham came to Canada as High Commissioner. Although fights with government troops were not very bloody during the 1838 rebellion, the Crown punished the rebels strongly. 850 were arrested. 12 were hanged, and 58 were sent to Australian penal colonies.

In 1839, Lord Durham was asked by the Crown to write a report on British North America. This was because of the rebellions. The Special Council that governed the colony from 1838 to 1841 made many changes. These aimed to improve economic and government matters, like land ownership and new schools. These changes became the basis for "responsible government" in the colony.

Many American colonists who stayed loyal to England left the 13 Atlantic colonies before American independence. They came to Canada, with many settling in southern Quebec. In the 19th century, Quebec saw several waves of immigration. People mainly came from England, Scotland, and Ireland. Around 1900, most immigrants to Quebec were from Ireland. But many also came from Germany and other parts of western Europe.

Province of Canada (1840-1867)

Lord Durham suggested that Upper Canada and Lower Canada be joined. This was to make the French-speaking people of Lower Canada a minority in the new area. This would weaken their influence. Durham stated his goals clearly. His suggestion was followed. The new government seat was in Montreal. Former Upper Canada was called "Canada West" and former Lower Canada was called "Canada East". The Act of Union 1840 created the Province of Canada. Rebellions continued sometimes. In 1849, the burning of the Parliament Buildings in Montreal led to the government moving to Toronto. Historian François-Xavier Garneau, like other French speakers in Canada East during the 1840s, worried deeply about this union. He worried about the place of French speakers within it.

This union caused political problems until 1867. The differences between the two cultural groups in the Province of Canada made it impossible to govern without forming coalition governments. Also, even though their populations were different, both Canada East and Canada West had the same number of seats in the Legislative Assembly. This caused representation problems. At first, Canada East had fewer representatives than it should have because it had more people. Over time, many people from the British Isles moved to Canada West, increasing its population. Since both regions still had equal representation, Canada West now had fewer representatives than it should have. The issue of representation was often debated, called "Representation by Population." When Canada West was under-represented, this became a rallying cry for reformers there.

In 1844, the capital of the Province of Canada moved from Kingston to Montreal.

During this time, Loyalists and immigrants from the British Isles stopped calling themselves English or British. Instead, they started calling themselves "Canadian", referring to Canada, where they lived. The "Old Canadians" reacted to this. They started to identify with their own ethnic group, calling themselves "French Canadian". So, the terms French Canadian and English Canadian were born. French Canadian writers began to think about how their own culture could survive. François-Xavier Garneau wrote an important national story. He wrote to Lord Elgin: "I started this work to show the truth, which is often twisted. I wanted to fight back against the attacks and insults my people face every day from those who want to control and use them." His and other writings helped French Canadians keep their shared identity. This protected them from losing their culture, much like the story Evangeline did for Acadians.

Political unrest reached a peak in 1849. English Canadian rioters set fire to the Parliament Building in Montreal. This happened after a law was passed to pay French Canadians whose property was destroyed during the rebellions of 1837–1838. This law was very important because it established the idea of responsible government. In 1854, the seigneurial system was ended. The Grand Trunk Railway was built. The Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty was put in place. In 1866, the Civil Code of Lower Canada was adopted. Then, the long period of political deadlock in the Province of Canada ended. The Macdonald-Cartier group began to reform the political system.

Confederation and Early Quebec (1867–1914)

In the years just before Canadian Confederation in 1867, French-speaking Quebecers, then called Canadiens, were the majority in Canada East. Between 1851 and 1861, about 75% of the population was French-speaking. About 20% were English-speaking people of British or Irish background. From 1871 to 1931, the number of French-speaking people stayed about the same. It reached a high of 80.2% of Quebec's population in 1881. The number of British-descended citizens slowly went down. It dropped from a high of 20.4% in 1871 to 15% by 1931. Other minority groups made up the rest of the province's population.

After several years of talks, in 1867, the British Parliament passed the British North America Acts. This joined the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia to form the Dominion of Canada. Canada East became the Province of Quebec. Canada could govern itself locally. But the British still controlled its foreign affairs.

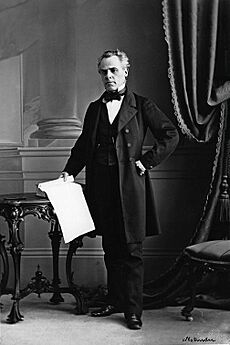

George-Étienne Cartier had fought as a Patriote in the Battle of Saint-Denis in 1837. Later, he became one of the Fathers of Confederation. He presented the 72 resolutions of the Quebec Conference of 1864. These were approved for creating a federated state, Quebec. Its land would be limited to the historic heart of the French Canadian nation. This was where French Canadians would most likely remain the majority. In the future, Quebec as a political area would protect against losing French culture. It would also help French Canadians assert their identity. This was important as the Canadian state would become more dominated by English-American culture. Despite this, the goals of the new federal government would make it hard for Quebec to assert itself. The power given to the provinces would be limited. Quebec, being weaker economically, would have to compete politically with Ottawa, the capital of the strong federal state. On July 15, 1867, Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau became Quebec's first Premier.

Grande Hémorragie

In the 1820s and 1830s, the population grew quickly. This made it hard for young people in Lower Canada to get land. Bad harvests and political problems in 1838–1839 put more stress on farming in the southern part of the colony. French Canadian farmers slowly adapted to competition and new economic realities. Some people at the time thought their farming methods were old-fashioned. Around this time, the textile industry in New England grew fast. Living conditions were harsh, and work was hard to find even in Montreal. So, many people felt that moving away was their only choice. As the first group moved in the 1850s, news spread. By the late 1870s, larger crowds started to move. Mill owners hired these French immigrants because they were cheaper than American and Irish workers.

When the first group of people left Quebec, the local government did not pay much attention. The numbers were small. However, when more people started leaving and the province's economy was in a depression, leaders tried to stop the emigration. A small group of thinkers believed French-Canadian culture could be kept alive in the U.S. But many more leaders warned against leaving. They argued that people would lose their culture and morals south of the border. Instead, they suggested settling new areas within Quebec and developing the St. Lawrence River valley. Nevertheless, over 200,000 people left between 1879 and 1901.

Growth of Montreal

Montreal grew a lot around the time of Confederation. French Canadians from rural areas moved to the city to find work. Immigrants came to Montreal, which was Canada's largest city then. Many people from other parts of Canada also moved there. Major businesses and banks were set up in Montreal. These included the main offices of several national banks and companies. Important businessmen included brewer and politician John Molson Jr., jeweler Henry Birks, and insurer James Bell Forsyth. Montreal's population grew quickly. It went from about 9,000 in 1800 to 23,000 in 1825, and 58,000 in 1852. By 1911, the population was over 528,000. The City of Montreal added many nearby communities. Its area grew five times between 1876 and 1918. Since Montreal was Canada's financial center then, it was the first Canadian city to use new inventions. These included electricity, streetcars, and radio.

-

The funeral of Thomas D'Arcy McGee in 1868. It drew 80,000 people from a city population of 110,000.

Influence of the Catholic Church

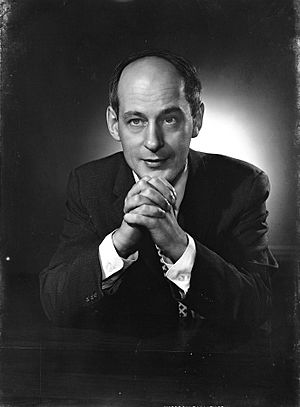

Many parts of life for French-speaking Quebecers were controlled by the Catholic Church after 1867. The Church ran many of the province's institutions. These included most French-language schools, hospitals, and charities. The leader of the Catholic Church in Quebec was the Bishop of Montreal. From 1840 to 1876, this was Ignace Bourget, who was against liberal ideas. Bourget eventually gained more influence than the reformist Institut Canadien. At one point, Bourget even refused a Church burial for Joseph Guibord, a member of the Institut, in 1874. A court decision forced Bourget to allow Guibord to be buried in a Catholic cemetery. But Bourget removed the sacred blessing from that burial spot. Guibord was buried under army protection. The conservative approach of the Catholic Church was a major force in Quebec society. This lasted until the reforms of the Quiet Revolution in the 1960s. In 1876, Pierre-Alexis Tremblay lost a federal election because the Church pressured voters. But he got his loss canceled with a new federal law. He quickly lost the next election. In 1877, the Pope sent representatives to make the Quebec Church interfere less in elections.

Catholic women started many independent religious orders. These were partly funded by money given by the parents of young nuns. The orders focused on charity work. This included hospitals, orphanages, homes for single mothers, and schools. In the first half of the 20th century, about 2-3% of young women in Quebec became nuns. There were 6,600 in 1901 and 26,000 in 1941. In Quebec in 1917, 32 different teaching orders ran 586 boarding schools for girls. At that time, there was no public education for girls in Quebec beyond elementary school. The first hospital was founded in 1701. In 1936, the nuns of Quebec ran 150 institutions. They had 30,000 beds to care for the sick, homeless, and orphans. Between 1870 and 1950, thousands of young girls were sent to Quebec City. They went to the reform school (1870–1921) and the industrial school (1884–1950) of the Hospice St-Charles. Both were run by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd.

Lionel Groulx wanted to build a strong French-Canadian identity. This was to protect the Church's power and discourage people from supporting popular rule and non-religious views. Groulx promoted French-Canadian nationalism. He argued that keeping Quebec Catholic was the only way to free the nation from English power. He believed the Quebec provincial government's powers could and should be used within Canada. This would strengthen provincial independence and Church power. He said it would help the French-Canadian nation economically, socially, culturally, and linguistically. Groulx successfully promoted Quebec nationalism and very conservative Catholic social ideas. The Church kept its control in Quebec's political and social life. In the 1920s–1950s, this type of traditional Catholic nationalism was known as clerico-nationalism.

-

Ignace Bourget, Bishop of Montreal, in 1862.

Politics

The execution of Métis rebel leader Louis Riel in Saskatchewan in 1885 caused protests in Quebec. French Canadians felt they were being unfairly treated because of their religion and language. Honoré Mercier became the strong leader of the protest movement. The federal Cabinet members of the Quebec Conservative Party had reluctantly supported Prime Minister Macdonald's decision to execute Riel. Support for Conservatives decreased.

Mercier saw a chance to form a group of his Liberals and unhappy Conservatives. He brought back the "Parti National" name for the 1886 Quebec provincial election. He won most of the seats. However, the group was mostly Liberals and only a few Conservatives. So, the "Liberal" name was soon used again. The Conservatives, with fewer members in the Legislative Assembly, held onto power for a few more months. Mercier became Premier of Quebec in 1887. He believed that provincial independence was how Quebec nationalism was expressed. He worked with Ontario premier Oliver Mowat to reduce the federal government's central power.

With his strong nationalist views, Mercier was a leader for future nationalist premiers. They would challenge the federal government and try to get more power for Quebec. He encouraged connections with French speakers in other parts of North America outside Quebec. This included Western Canada and New England. Those French speakers had not yet lost their culture to English-Canadian or American culture. Mercier promoted reforms, economic growth, Catholicism, and the French language. He was re-elected to the legislature and his party won the 1890 election with more support. He was defeated in 1892.

In 1896, Wilfrid Laurier became the first French Canadian to be Prime Minister of Canada. Laurier was educated in both French and English. He stayed in office as Prime Minister until October 1911. Laurier had several important political successes in Quebec. Among them, he won Quebec votes for the Liberal Party, even though the powerful Catholic clergy did not want him to.

In 1899, Henri Bourassa spoke strongly against the British government's request for Canada to send soldiers to fight for Britain in the Second Boer War. Laurier's compromise was to send a volunteer force. But this started the issue of conscription protests during future world wars. Bourassa also opposed building warships to help protect the empire, but he was unsuccessful. He led the opposition to mandatory conscription during World War I. He argued that Canada's interests were not at risk. He opposed Catholic bishops who supported military help for Britain and its allies.

Boundary Extensions

As more provinces joined Canada, there was a strong need to set clear provincial borders. In 1898, the Canadian Parliament passed the Quebec Boundary Extension Act, 1898. This gave Quebec a part of Rupert's Land, which Canada had bought in 1870. This Act made Quebec's borders extend northward. In 1912, the Canadian Parliament passed the Quebec Boundaries Extension Act, 1912. This gave Quebec another part of Rupert's Land: the District of Ungava. This extended Quebec's borders northward all the way to the Hudson Strait.

People moving also shaped life in late 19th century Quebec. In the late 1800s, too many people in the Saint Lawrence Valley led many Quebecers to move. They went to the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region, the Laurentides, and New England. This created a link with New England that still exists today. In 1909, the government passed a law. It required wood and pulp to be processed in Quebec. This helped slow the Grande Hémorragie. It allowed Quebec to export finished products to the US instead of its workers. Clerico-nationalists started to lose favor in the federal elections of 1911.

In 1927, the British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council drew a clear border between northeast Quebec and south Labrador. However, the Quebec government did not accept this ruling. This led to a border dispute. The Quebec-Labrador border dispute is still ongoing today. Some say Quebec's borders are the most unclear in the Americas.

Early 20th Century Quebec (1915-1959)

First World War

When World War I started, Canada was automatically involved as a British Dominion. Many English Canadians volunteered to fight. Unlike English Canadians, French Canadians felt no connection to anyone in Europe. Also, Canada was not threatened by the enemy, who was far away and not interested in conquering Canada. So, French Canadians saw no reason to fight. Still, a few French Canadians did join the 22nd Battalion. By late 1916, the terrible number of deaths caused problems with getting enough soldiers. After great difficulty in the federal government, the Military Service Act became law on August 29, 1917. Almost every French-speaking Member of Parliament was against conscription, while almost all English-speaking MPs supported it. French Canadians protested in what is now called the Conscription Crisis of 1917. The protests grew so much that they led to the Quebec riot of 1918.

Great Depression

The worldwide Great Depression began in 1929. It hit Quebec hard. Exports, prices, profits, and wages dropped sharply. Unemployment rose to 30%, and even higher in logging and mining areas. Politically, there was a shift to the right. Quebec's leaders saw that failures of capitalism and democracy around the world had led to the spread of socialism, totalitarianism, and civil war. The Spanish Civil War especially worried religious Catholics. They demanded that Canada keep out representatives of Spain's anti-Catholic government. There was a wave of religious and Quebec nationalism. This showed a conservative reaction from a traditional society that feared social change would threaten its survival.

With so many men unemployed or earning less, it was a big challenge for housewives to manage with little money and resources. They often used strategies their mothers had used when growing up in poor families. They used cheap foods like soups, beans, and noodles. They bought the cheapest cuts of meat, sometimes even horse meat. They reused Sunday roast for sandwiches and soups. They sewed and patched clothes, traded with neighbors for outgrown items, and kept their houses colder. New furniture and appliances were put off until better times. These strategies show that women's work at home—cooking, cleaning, budgeting, shopping, childcare—was essential to the family's economic survival. Most women also worked outside the home, or took in boarders, did laundry for trade or cash, and sewed for neighbors in exchange for something they could offer. Extended families helped each other with extra food, spare rooms, repairs, and cash loans. The number of births nationwide fell from 250,000 in 1930 to about 228,000 and did not recover until 1940.

The poet Emile Coderre (1893–1970), writing as "Jean Narrache," gave a voice to the poor people of Montreal. They struggled to survive during the Great Depression. Writing in street language, Narrache took on the role of a poor man. He thought about the ironies of small social assistance, the role of social class, the false claims of rich business people, and the fake charity of the wealthy.

There was political unhappiness. More and more voters complained that both Prime Minister Bennett and the Conservative party, and provincial Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau and the Liberal party, were uncaring and unable to do their jobs. Many unhappy people turned to nationalist leaders. These included Henri Bourassa, editor of Le Devoir, and the very traditional Catholic writer Lionel Groulx, editor of L'action canadienne-française. Building on this unhappiness, Maurice Duplessis led the new Union nationale party to victory in 1936. He won with 58% of the vote and became premier.

Second World War

Good times returned with the Second World War. Demand for Quebec's workers, raw materials, and manufactured goods soared. 140,000 young men, both French and English speaking, quickly joined the military. However, English was the main language in all services, and needed for promotions.

Duplessis expected to win the election by using anti-war feelings when he called an election in the fall of 1939. He miscalculated. The Liberals won by a landslide, with 70 seats to only 14 for the Union nationale.

Canadian leaders managed to avoid the deep conscription crisis that had caused bad feelings between English and French speakers during the First World War. During the Conscription Crisis of 1944, Quebecers protested conscription. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King tried to avoid full conscription in Canada, but it became a reality in the final months of World War II. However, the end of the war also meant the end of the crisis. MacKenzie King successfully presented himself as "a moderate." At the same time, he "limited the ethnic bitterness" that had marked the 1917 conscription crisis.

Grande Noirceur

Duplessis returned as premier in the 1944 election. He held power without serious opposition for the next fifteen years, until his death. He won elections in 1948, 1952, and 1956. He became known simply as le Chef ("the boss"). He supported rural areas, provincial rights, and was against Communism. He opposed trade unions, modernizers, and intellectuals. He worked well with the powerful English businessmen who controlled most of the economy. Duplessis and his Union Nationale party were very controversial. They dominated the province. Duplessis' years in power have been called the La Grande Noirceur ("Great Darkness") by his opponents. The Duplessis years had close ties between the church and the government. Quebec society remained culturally isolated during this time. This was different from the modern changes happening in the rest of North America. Traditional Catholic morals and church teachings shaped many parts of daily life, emphasizing old ways. For example, most schools and hospitals were controlled by the Church. Divorce was not fully legal in Quebec until 1968.

People who wanted reform spoke out during the Duplessis years. But such challenging ideas were often disapproved of and pushed aside. In 1948, a group of artists called Les Automatistes published Le Refus global, meaning "total refusal." This pamphlet tried to start a new vision for Quebec. It has been called "an anti-religious and anti-establishment manifesto and one of the most influential social and artistic documents in modern Quebec history." It would have a lasting effect, influencing supporters of Quebec's Quiet Revolution in the 1960s.

Other signs of frustration with the way things were appeared with the difficult Asbestos Strike of 1949. It led to a greater understanding of workers' rights and social-democratic issues in Quebec.

In the fall of 1950, Rivière-du-Loup had a nuclear accident. A U.S. Air Force plane was returning a nuclear bomb to the USA. The bomb was released because of engine problems. It was then destroyed in a non-nuclear explosion before it hit the ground. The explosion spread nearly 100 pounds (45 kg) of uranium.

The Union Nationale often had the active support of the Roman Catholic Church during political campaigns. They used the slogan Le ciel est bleu; l'enfer est rouge ("Heaven is blue; hell is red"). Red is the color of the Liberal party, and blue was the color of the Union Nationale.

Late 20th Century Quebec (1960-1999)

Quiet Revolution (1960–1980)

During the 1960s, the Quiet Revolution brought many social and political changes. These included less church control, a welfare state, and a specific Quebec identity. The baby boom generation embraced these changes. They made social attitudes in the province more liberal.

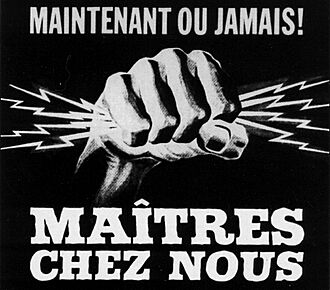

In 1960, the Liberal Party of Quebec won power. They campaigned with the slogan "It's time for things to change." This new government, led by Jean Lesage, had a strong team. They made many reforms in social policy, education, health, and economic development. They also created important organizations like the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec and the Ministry of Education.

The Quiet Revolution was especially known for the Liberal Party's 1962 slogan, "Masters in our own house." To the large English-American companies that controlled Quebec's economy and natural resources, this slogan announced that French-Canadian people wanted freedom.

Arguments began between the lower clergy (church officials) and the laity (regular church members). As a result, government services started to be provided without the church's help. Many parts of society became less religious. During the Second Vatican Council, the Pope supported the reform of Quebec's institutions. In 1963, Pope John XXIII issued an encyclical called Pacem in Terris, which established human rights. In 1964, Lumen Gentium confirmed that regular church members had a special role in managing worldly matters.

In 1965, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism wrote a first report. It highlighted Quebec's unique character. It promoted open federalism, a political approach that guaranteed Quebec a minimum level of consideration. To help Quebec during its Quiet Revolution, Canada, through Lester B. Pearson, adopted a policy of open federalism. In 1966, the Union Nationale was re-elected and continued with major reforms.

The changes of the 1960s also brought conflict for some in Quebec. The rise of extreme nationalist violence marked a dark time. In 1963, the first bombs of the Front de libération du Québec exploded in Montreal. A major recognition of Quebec's cultural importance came in 1964. The Province of Quebec signed its first international agreement in Paris. This was allowed by the Government of Canada. The same year, during a visit by the Queen, police had to keep order during a protest by Quebec separatist groups.

As a result of conflicts between the lower clergy and regular church members, government services began to be provided without the church's help. Many parts of society became less religious. During the Second Vatican Council, the Pope supported the reform of Quebec's institutions. In 1965, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism wrote a first report. It highlighted Quebec's unique character. It promoted open federalism, a political approach that guaranteed Quebec a minimum level of consideration. To help Quebec during its Quiet Revolution, Lester B. Pearson adopted a policy of open federalism. In 1966, the Union Nationale was re-elected and continued with major reforms.

In 1967, French President Charles de Gaulle visited Quebec. He was the first French head of state to do so. He came for Expo 67. There, he spoke to over 100,000 people. He ended his speech with "Long live free Quebec!" This statement had a big effect on Quebec. It boosted the growing modern Quebec sovereignty movement. It also caused a political crisis between France and Canada. After this, various citizen groups formed. They sometimes challenged public authority, for example, in the October Crisis of 1970. Meetings in November 1967 marked a turning point. Relations between French speakers in America, especially in Canada, broke down. This greatly affected Quebec society's development.

In 1968, class conflicts and changes in attitudes grew stronger. That year, Option Quebec started a debate about the province's political future. It set federalist and sovereignist ideas against each other. In 1969, the federal Official Languages Act was passed. It aimed to create a language environment that would help Quebec develop. In 1973, the Liberal government of Robert Bourassa started the James Bay Project. This project on the La Grande River expanded Hydro-Québec's power. It created one of the largest hydro-electric projects in the world. In 1974, it passed the Official Language Act. This made French the official language of Quebec. In 1975, it established the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms and the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement.

Expo 67

The 1960s were mostly a time of hope in Quebec. Expo 67 marked Montreal's peak as Canada's largest and most important city. It led to the building of what is now Parc Jean Drapeau and the Montreal Metro. In 1962, Montreal's mayor, Jean Drapeau, started building the Metro (subway). The first part of the subway was finished in 1966. These huge projects happened at the same time as Canada's 100th birthday celebrations in 1967. A wave of patriotism swept through most of Canada.

Religion and Culture

Amidst the powerful urban changes, cultural change also took root. Quebec was greatly affected by the baby boom. Between 1960 and 1970, over 1.2 million Quebecers turned 14. As more young Quebecers rejected Catholic teachings, they made life choices that were a complete change from tradition. The number of young couples living together rose, as marriage slowly became less of a requirement. Births outside of marriage began to rise, from 3.7 percent in 1961 to 10 percent in 1976, then 22 percent by 1984. As of 2015, 62.9% of births were outside of marriage.

Student protests happened at local universities. These were similar to youth protests across the United States and Western Europe in the 1960s and early 1970s. Reforms included more opportunities for higher education for both English- and French-speaking Quebecers. In 1968, the Université du Québec à Montréal opened. Protests by English-speaking students led to the creation of Concordia University in Montreal that same year. The Quiet Revolution combined less church control with the Church reforms of Vatican II. There was a big change in the role of nuns. Many left the convent, and very few young women joined. The provincial government took over the nuns' traditional role of providing many of Quebec's educational and social services. Former nuns often continued the same jobs in regular clothes. For the first time, men started entering the teaching profession.

With the Quiet Revolution, Quebecers showed their identity, especially in arts, culture, and language. During this revolution, the Quebec government formed the Ministry of Culture. It focused mainly on protecting the French language and culture. Quebec's transformation was also marked by a law on health insurance. This guaranteed universal health care through a tax-funded public system. In 1964, Quebec recognized equality between men and women. It allowed all women to have jobs that were once only for men.

Politics and Independence

The growth of Quebec's government and its perceived interference caused problems with the federal government. This was especially true because the federal government wanted to centralize power.

English-speaking Canada worried about the changes in Quebec society and the protests of the Quebecers. In 1963, Canada's Prime Minister, Lester B. Pearson, asked, "What does Quebec want?" He started a royal commission to study bilingualism and biculturalism. Its goal was to answer this question and suggest ways to meet the demands of the Quebecers. French-speaking communities outside Quebec also pushed for more language and cultural support. In 1965, the Laurendeau-Dunton royal commission report suggested making French an official language. This would apply in the parliaments of Canada, the provincial assemblies of Ontario and New Brunswick, in federal courts, and in all federal government administration.

Putting these suggested changes into practice only made the gap between English Canada and French-speaking Quebecers wider. English Canadians thought the changes were unacceptable concessions. French speakers thought they were not enough.

Friction with English Canada made the idea of independence from Canada more popular.

In 1967, René Lévesque left the Quebec Liberal Party. He founded the Mouvement Souveraineté-Association. The Ralliement national (RN) and the Rassemblement pour l'indépendance nationale (RIN) were founded in 1960. They quickly became political parties. In 1967, René Lévesque, who had been a leading figure in the Quebec Liberal Party, left the Liberals to found the Mouvement Souveraineté-Association (MSA).

In 1968, the sovereignists reorganized into one political party, the Parti Québécois. It was led by René Lévesque. Pro-independence parties gained 8% of the popular vote in Quebec in 1966, 23% in 1970, and 30% in 1973.

During an official visit to Quebec, French President Charles de Gaulle spoke from the balcony of Montreal city hall. He was a guest of the Canadian government. He said, "Long live free Quebec!" This was not diplomatic. The Canadian federal government was very offended. De Gaulle suddenly canceled his visit to Ottawa and went home.

Violence broke out in 1970 with the October Crisis. Members of the Front de libération du Québec kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross and Quebec Minister of Labour Pierre Laporte. Pierre Laporte was later found murdered. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau used the War Measures Act. This law allowed anyone suspected of being involved with the terrorists to be held temporarily without charge.

Economic Challenges

During this time, several things caused the buying power of Quebecers to stop growing or even shrink:

- Gas price shocks in 1973–1974 and 1979 caused prices to rise and interest rates to be high.

- Taxes increased to pay for government programs started between 1960–1975.

- Governments, struggling with spending and growing debt, stopped providing some services. Citizens now had to pay for these themselves.

- The global economy put pressure on salaries to stay low.

1980 Referendum

In 1976, the separatist Parti Québécois, led by René Lévesque, was elected. They formed the province's first separatist government. The Parti Québécois promised during its campaign that it would not declare independence without getting approval through a referendum. The Parti Québécois' goal was to govern the province well, not to bring about independence right away. The first years of the Parti Québécois government were very productive. The government passed progressive laws that were well accepted by most people. These included French language protection laws, a law on funding political parties, laws for helping road accident victims, for protecting farm land, and many other social-democracy-type laws. Even opponents of the Parti Québécois sometimes admitted that the Party governed the province well.

On May 20, 1980, the first referendum was held on sovereignty-association. But it was rejected by a majority of 60 percent ("No" 59.56%, "Yes" 40.44%). Polls showed that most English speakers and immigrants voted against it. French speakers were almost equally divided.

Constitution Act of 1982

Along with the Canada Act 1982, a law passed by the British Parliament, this Act cut almost all remaining constitutional and legal ties between the United Kingdom and Canada. All provinces except Quebec signed the Act.

On the night of November 4, 1981, Federal Justice Minister Jean Chrétien met with all provincial premiers except René Lévesque. They signed the document that would become the new Canadian constitution. The next morning, they presented the finished document to Lévesque. Lévesque refused to sign it and returned to Quebec. In 1982, Trudeau had the new constitution approved by the British Parliament. Quebec's signature was still missing, and this situation continues today. Quebec is the only province that has not formally agreed to the Canadian constitution being brought home in 1982.

Meech Lake Accord and Charlottetown Accord

Between 1982 and 1992, the Quebec government's attitude changed. It focused on reforming the federation. Later attempts to change the constitution by the Mulroney and Bourassa governments failed. This included both the Meech Lake Accord of 1987 and the Charlottetown Accord of 1992. These failures led to the creation of the Bloc Québécois.

1995 Referendum

On October 30, 1995, a second referendum for Quebec sovereignty was rejected by a small difference. The "No" side got 50.58%, and the "Yes" side got 49.42%. Key leaders for the Quebec separatist side were Lucien Bouchard and Quebec Premier Jacques Parizeau. Bouchard had left Prime Minister Brian Mulroney's Progressive Conservative government. He formed Canada's first federal separatist party, the Bloc Québécois, in 1991. He became the leader of the Opposition after the 1993 federal election. He campaigned strongly for the "Yes" side against Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, who strongly supported the federalist "No" side. Parizeau, a long-time separatist, had played an important role in the 1980 referendum. He promised a referendum for sovereignty in his campaign before the 1994 provincial election. This earned him a majority government in the province. After the referendum, he was criticized. He blamed the loss on "money and the ethnic vote" in his speech after the results. Parizeau resigned as Premier and as leader of the Parti Québécois the day after his controversial speech. He claimed he had always planned to do so if the separatists lost. Bouchard left federal politics to replace him in January 1996.

Federalists said the sovereignist side asked a vague and too complicated question on the ballot. Its English text was:

Do you agree that Québec should become sovereign after having made a formal offer to Canada for a new economic and political partnership within the scope of the bill respecting the future of Québec and of the agreement signed on June 12, 1995?

In 1998, the Supreme Court of Canada made a decision about Quebec's right to separate. After this, the Parliaments of Canada and Quebec set out the legal rules for how their governments would act in another referendum.

21st Century Quebec (2000-Present)

On October 30, 2003, the National Assembly voted unanimously. They affirmed "that the people of Québec form a nation."

After winning the provincial election in 1998, Bouchard retired from politics in 2001. Bernard Landry was then appointed leader of the Parti Québécois and premier of Quebec. In 2003, Landry lost the election to the Quebec Liberal Party and Jean Charest. Landry stepped down as PQ leader in 2005. In a crowded race for the party leadership, André Boisclair was elected to succeed him.

On November 27, 2006, the House of Commons of Canada passed a motion. It recognized that the "Québécois form a nation within a united Canada." The federal government introduced this motion.

In January 2007, the town of Hérouxville gained attention. It approved a code of conduct for immigrants. This happened during a debate on "reasonable accommodation" for other cultures in Quebec. This debate would lead to the Parti Québécois' Quebec Charter of Values.

Quebec elected Pauline Marois as its first female premier on September 4, 2012. Marois was the leader of the Parti Québécois.

During the 2011 Canadian federal elections, Quebec voters rejected the sovereignist Bloc Québécois. Instead, they voted for the federalist and previously small New Democratic Party (NDP). Since the NDP's logo is orange, this event was called the "orange wave."

Marois called a provincial election for April 2014. Her party was defeated by the Quebec Liberal Party (PLQ). The PLQ won by a large margin, securing a majority government. In the 2018 Quebec general election, the Coalition Avenir Québec defeated the Liberals, forming a majority government. François Legault is the current Premier.

In May 2017, floods spread across southern Quebec. Montreal declared a state of emergency.

In 2018, the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), led by François Legault, won the provincial general elections. This was the first time since the 1966 election that a party other than the Quebec Liberals or the Parti Québécois formed the government in Quebec.

In June 2019, Quebec passed Bill 21. This law stops public servants from wearing religious symbols while on duty.

In the 2019 Canadian federal election, The Bloc Québécois increased its number of seats from 10 in 2015 to 32 seats in 2019. It overtook the NDP to become the third largest party in Canada. It also regained official party status.

Between 2020 and 2021, Quebec took steps to protect itself against the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2022, the provincial legislature passed An Act respecting French, the official and common language of Québec. This law made it more often required to speak French in many public and private places. It strengthened French as the language of laws, justice, government, professional groups, employers, trade, business, and education.

The Coalition Avenir Québec Government increased its majority in the 2022 Quebec general election.

|