History of the Dominican Republic facts for kids

The history of the Dominican Republic started in 1492. That's when a navigator named Christopher Columbus, who was working for Spain, found a big island in the Caribbean Sea. This island was home to the Taíno people, who called the eastern part of it Quisqueya, meaning "mother of all lands." Columbus claimed the island for Spain and named it La Isla Española, which later became Hispaniola.

After 25 years of Spanish rule, the Taíno population on the Spanish side of the island dropped a lot due to violence and disease. The few who survived mixed with Spaniards, Africans, and others, forming the people we know today as Dominicans. The area that became the Dominican Republic was a Spanish colony called the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo until 1821. It was also a French colony for a short time (1795-1809).

From 1822 to 1844, the island was united with Haiti. In 1844, the Dominican Republic declared its independence. The country, often called Santo Domingo until the early 1900s, stayed independent except for a brief Spanish rule (1861-1865) and a time when the United States occupied it (1916-1924).

During the 1800s, Dominicans often fought wars against the French, Haitians, Spanish, or even among themselves. This led to a society where powerful leaders called caudillos often ruled like kings. Between 1844 and 1914, the Dominican Republic had 53 presidents, but only 3 finished their terms! Many leaders took power by force.

Around 1930, Rafael Trujillo became a dictator and ruled the country until he was killed in 1961. Juan Bosch was elected president in 1962 but was removed by the military in 1963. In 1965, a civil war started to bring Bosch back. The United States then stepped in. In 1966, Joaquín Balaguer, another caudillo, won the presidential election. Balaguer held power for most of the next 30 years. After some problems with elections, he had to shorten his term in 1996. Since then, the Dominican Republic has had regular elections where different candidates have won the presidency.

Contents

- Ancient History: Before Europeans Arrived

- Spanish Colony: 1492–1795

- French Occupation: 1801–1809

- Spanish Rule and Haitian Takeover: 1809–1844

- Independence: The First Republic (1844–1861)

- Spanish Colony: 1861–1865

- Restoration: The Second Republic (1865–1916)

- United States Occupation: 1916–1924

- The Rise and Fall of Trujillo: The Third Republic (1924–1965)

- Dominican Civil War and Second United States Occupation: 1965–1966

- The Fourth Republic: 1966–Present

- Balaguer's Second Presidency: 1966–1978

- Guzmán / Blanco Interregnum: 1978–1986

- Balaguer's Third Presidency: 1986–1996

- Fernández: First Administration: 1996–2000

- Mejía's Administration: 2000–2004

- Fernández: Second Administration: 2004–2012

- Danilo Medina's Administration: 2012–2020

- Luis Abinader: 2020–Present

- See also

- Images for kids

Ancient History: Before Europeans Arrived

The Caribbean islands were first settled about 6,000 years ago by people who hunted and gathered food. These people came from Central or northern South America. The ancestors of the Taíno people, who spoke Arawakan languages, arrived in Hispaniola around 600 AD. They were farmers, fishers, hunters, and made pottery.

It's hard to know exactly how many people lived on Hispaniola in 1492 when Columbus arrived. Estimates range from tens of thousands to millions. At that time, the island was divided into five Taíno chiefdoms. These were Marién, Maguá, Maguana, Jaragua, and Higüey. Each was ruled by a chief called a cacique. The Taíno name for the whole island was either Ayiti (land of high mountains) or Quisqueya (mother of all lands).

Spanish Colony: 1492–1795

Arrival of the Spanish

Christopher Columbus reached Hispaniola on his first trip in December 1492. The chief, Guacanagarí, welcomed Columbus and his men kindly. However, the Europeans' way of life, with strict social classes, clashed with the Taíno's more equal system. The Europeans started treating the Taíno people with violence. Columbus tried to stop this, and he and his men left on good terms.

After his ship, the Santa María, sank, Columbus built a small fort called La Navidad. While Columbus was away, the men at the fort fought among themselves and terrorized the Taíno. Chief Caonabo of the Maguana Chiefdom attacked the Europeans and destroyed La Navidad.

In 1493, Columbus returned and founded the first Spanish colony in the New World, called La Isabela. It almost failed due to hunger and sickness. In 1496, Santo Domingo was built and became the new capital. It is the oldest European city in the Americas that has been continuously lived in.

About 400,000 Taínos on the island were soon forced to work in gold mines. By 1508, their numbers had dropped to about 60,000 because of hard labor, hunger, disease, and killings. By 1535, only a few dozen were left. Many people describe the treatment of the Taíno under Spanish rule as a genocide.

One rebel, Enriquillo, fought back successfully. He led a group into the mountains and attacked the Spanish for fourteen years. The Spanish finally offered him a peace treaty in 1534, giving him and his followers their own town.

The 1500s: Sugar and Slavery

In 1501, the Spanish rulers allowed colonists to bring African slaves to the Caribbean. The first large group arrived in Hispaniola in 1510. Sugar cane was brought to Hispaniola, and the first sugar mill in the New World was built there in 1516. The demand for workers to grow sugar cane led to a huge increase in importing slaves.

The first major slave revolt in the Americas happened in Santo Domingo on December 25, 1521. Enslaved Muslims from the Wolof people led an uprising on a sugar plantation. Many of these rebels escaped to the mountains and formed independent communities called maroons.

While sugar cane made Spain a lot of money, many newly imported slaves ran away to the mountains. By the 1530s, these cimarrón groups were so large that Spaniards could only travel safely in big armed groups.

Starting in the 1520s, French pirates attacked ships in the Caribbean. In 1541, Spain allowed Santo Domingo to build a fortified wall. In 1564, the island's main inland cities, Santiago de los Caballeros and Concepción de la Vega, were destroyed by an earthquake. English privateers also joined the French in raiding Spanish ships.

After Spain conquered the American mainland, Hispaniola became less important. Most Spanish colonists left for the silver mines of Mexico and Peru. Agriculture decreased, and new slave imports stopped. White colonists, free blacks, and slaves lived in poverty, leading to more mixing of different groups. Except for Santo Domingo, other Dominican ports relied on illegal trade.

In 1586, the English privateer Francis Drake captured Santo Domingo and demanded money for its return. In 1592, Christopher Newport of England attacked and robbed the town of Azua.

The 1600s: French and English Influence

In 1605, Spain was angry that settlements on the northern and western coasts were trading illegally with the Dutch and English. So, Spain forced the people living there to move closer to Santo Domingo. This action, called the Devastaciones de Osorio, was a disaster. More than half of the moved colonists died, and many slaves escaped. Five settlements were destroyed by Spanish troops.

French and English buccaneers took advantage of Spain's retreat. They settled on the island of Tortuga in 1629, off the northwest coast of Hispaniola. France took direct control in 1640 and expanded into Hispaniola itself. Spain gave the western part of the island to France in 1697 under the Treaty of Ryswick.

In 1655, Oliver Cromwell of England sent a fleet to capture Santo Domingo. The English were defeated but captured the nearby Spanish colony of Jamaica. Santo Domingo also suffered from smallpox, a cacao disease, and hurricanes.

The 1700s: Revival and Revolution

In 1700, Spain's new rulers, the House of Bourbon, made economic changes that slowly helped trade in Santo Domingo. They eased strict rules on trade between Spain and its colonies. By the mid-1700s, the population grew with people from the Canary Islands. They settled the northern part of the colony and grew tobacco. Slave imports also started again. The population of Santo Domingo grew from about 6,000 in 1737 to around 125,000 in 1790.

When the War of Jenkins' Ear started in 1739, Spanish privateers from Santo Domingo began to patrol the Caribbean. They attacked enemy ships, bringing captured goods back to Santo Domingo. This helped the colony's economy and led to more people moving there from Europe.

As trade rules became more relaxed, the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) became the main market for Santo Domingo's exports like beef, hides, and tobacco. When the Haitian Revolution began in 1791, many rich Spanish families fled the island. Spain tried to take advantage of the unrest to gain control of the western part of the island. But after the slaves and French made peace, Spain lost, and in 1795, France gained control of the entire island under the Treaty of Basel.

French Occupation: 1801–1809

In 1801, Toussaint Louverture arrived in Santo Domingo and declared an end to slavery for the French Republic. Soon after, Napoleon sent an army that took control of the whole island for a few months. However, mixed-race and black people rose up again in October 1802 and finally defeated the French in November 1803. On January 1, 1804, they declared Saint-Domingue an independent republic called Haiti.

Even after their defeat, a small French army stayed in Santo Domingo. Slavery was brought back, and many Spanish colonists who had left returned. In 1805, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the ruler of Haiti, invaded Santo Domingo but had to retreat. As they retreated, the Haitians looted towns like Santiago and Moca, killing many residents.

The French held onto the eastern part of the island until Dominican General Juan Sánchez Ramírez dealt them a big blow at the Battle of Palo Hincado on November 7, 1808. With help from the British Navy, Ramírez surrounded Santo Domingo. The French finally gave up on July 9, 1809. This started a twelve-year period of Spanish rule, known as "the Foolish Spain."

Spanish Rule and Haitian Takeover: 1809–1844

The new Spanish colony had about 104,000 people. Around 30,000 were slaves, mostly working on cattle ranches. The rest were a mix of Spanish, Taíno, and black people. There were few Europeans from Spain.

During this time, the Spanish crown had little power in Santo Domingo. Some rich cattle ranchers became leaders. On December 1, 1821, José Núñez de Cáceres, the former Spanish governor, declared the independence of "Spanish Haiti."

The white and mixed-race slave owners in the eastern part of the island were worried about attacks from Spain and Haiti. They also wanted to keep their slaves. So, they tried to join Gran Colombia. While they waited for a response, Jean-Pierre Boyer, the ruler of Haiti, invaded Santo Domingo on February 9, 1822, with a large army. Núñez de Cáceres had no way to fight back and surrendered the capital.

The twenty-two years of Haitian rule that followed are remembered by Dominicans as a harsh military period. It led to land being taken away, failed attempts to force people to grow crops for export, and restrictions on the Spanish language and customs. This time made Dominicans feel even more different from Haitians in terms of language, race, religion, and customs. However, it also ended slavery in the eastern part of the island for good.

Haiti's constitution did not allow white people to own land, so major landowning families lost their properties. Most moved to Cuba, Puerto Rico, or Gran Colombia. The Haitians also took church property and closed Santo Domingo's university. To get France to recognize Haiti's independence, Haiti had to pay a huge amount of money to former French colonists. Haiti then put heavy taxes on the eastern part of the island. Since Haiti couldn't properly supply its army, the soldiers often took food and supplies by force.

Attempts to give out land conflicted with the traditional system of shared land. Newly freed slaves didn't like being forced to grow cash crops. In rural areas, the Haitian government was often too weak to enforce its laws. The effects of the occupation were felt most strongly in Santo Domingo city, and that's where the independence movement began.

Independence: The First Republic (1844–1861)

Quick facts for kids War of Independence |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,000 militia | 40,000+ regulars | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Battle deaths (1844) < 20 |

Battle deaths (1844) 3,000+ |

||||||

| The Dominicans reportedly did not hesitate to attack with the odds against them of sometimes five to one. | |||||||

On July 16, 1838, Juan Pablo Duarte and others formed a secret group called La Trinitaria. Their goal was to gain independence from Haiti. Soon, Ramón Matías Mella and Francisco del Rosario Sánchez joined them. In 1843, they helped a Haitian movement overthrow Boyer. Because they showed they wanted Dominican independence, the new Haitian president, Charles Rivière-Hérard, exiled or imprisoned the main Trinitarios.

At the same time, Buenaventura Báez was talking with the French about making the Dominican Republic a French protectorate. To stop Báez, the Trinitarios declared independence from Haiti on February 27, 1844. They expelled all Haitians and took their property. The Trinitarios were supported by Pedro Santana, a rich cattle rancher who had his own army.

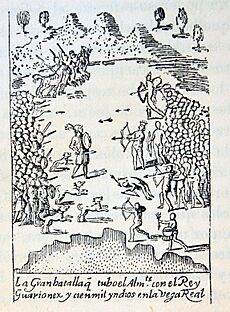

In March 1844, Haiti sent 30,000 troops to take back the Dominican Republic. But the Dominicans fought hard, causing many Haitian casualties and forcing them to retreat within a month. The Dominicans also fought off Haitian invasions in 1845, 1849, and 1855.

Early Leaders and Challenges

In July 1844, Pedro Santana took power from President Francisco del Rosario Sánchez in a military takeover. Santana started a military dictatorship.

The Dominican Republic's first constitution was approved on November 6, 1844. It set up a presidential government. However, Article 210, forced by Santana, gave him dictatorial powers during the war of independence. He used these powers to win the war and also to punish or exile his political rivals, including Duarte. Santana even had María Trinidad Sánchez executed.

For the first ten years of independence, Haiti and the Dominican Republic were often at war. Santana used the constant threat of Haitian invasion to keep his dictatorial powers. Many Dominican leaders, especially landowners and merchants, wanted protection from a foreign power. They offered the deepwater harbor of Samaná bay to countries like Britain, France, the United States, and Spain in exchange for protection.

In 1848, Santana had to resign and was replaced by Manuel Jimenes. After leading Dominican forces against a new Haitian invasion in 1849, Santana marched on Santo Domingo and removed Jimenes. He then had Congress elect Buenaventura Báez as president. Báez attacked Haitian villages, looting and burning them.

In 1853, Santana was elected president again, forcing Báez into exile. After stopping the last Haitian invasion, Santana tried to lease part of the Samaná Peninsula to a U.S. company. People opposed this, forcing him to step down, which allowed Báez to return to power. Báez printed a lot of money, which caused inflation and ruined tobacco farmers. The farmers revolted, bringing Santana back from exile to lead them. After a year of civil war, Santana took Santo Domingo and became president.

Spanish Colony: 1861–1865

| War of Restoration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

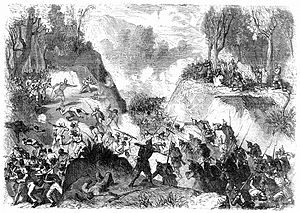

Battle of Monte Cristi |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,000–17,000 guerrillas |

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

Pedro Santana took over a government that was broke and about to collapse. After failing to get the U.S. or France to annex the island, Santana started talks with Queen Isabella II of Spain to make the island a Spanish territory again. The American Civil War meant the United States couldn't stop this. In March 1861, Santana officially returned the Dominican Republic to Spain. Many people did not like this, and there were several failed uprisings. On July 4, 1861, former President Francisco del Rosario Sánchez was captured and executed by Santana after leading a failed invasion.

The War of Restoration

On August 16, 1863, a national war of restoration began. Rebels defeated Spanish troops. On September 4, Spanish reinforcements marched towards Santiago but were defeated by rebels. The rebels then burned the town and surrounded the forts again. On September 14, the Spanish left Santiago, and the rebels formed a temporary government there. Santana, who had been given a special title by Queen Isabella II, was first named governor of the new Spanish province. But it became clear that Spain wanted to take away his power, so he resigned in 1862. Santana died in 1864.

The Spanish army could not defeat the guerrillas and suffered many losses from yellow fever. Spanish leaders encouraged Queen Isabella II to give up the island. The rebels were not united and couldn't agree on demands. The first president of the temporary government, Pepillo Salcedo, was removed by General Gaspar Polanco in September 1864. Polanco was then removed by General Antonio Pimentel three months later. In February 1865, the rebels held a meeting and created a new constitution. But the new government had little control over the different local caudillos. When the American Civil War ended, in March 1865, Queen Isabella canceled the annexation, and independence was restored. The last Spanish troops left by July.

Restoration: The Second Republic (1865–1916)

By the time the Spanish left, most main towns were in ruins. The island was divided among many local caudillos. José María Cabral controlled the southwest, while Cesáreo Guillermo led former Santana supporters in the southeast. Gregorio Luperón controlled the north coast.

From the Spanish leaving until 1879, there were 21 changes in government and at least 50 military uprisings. Two main political parties emerged. The Partido Rojo (Red Party) represented southern landowners and wanted to be annexed by a foreign power. The Partido Azul (Blue Party), led by Luperón, represented northern tobacco farmers and merchants. They were nationalist and liberal.

During these wars, the small national army was much smaller than the militias organized by local caudillos. These militias were made up of poor farmers who often became bandits when not fighting.

After the nationalist victory, Cabral took power but was soon forced to resign. This allowed Báez to become president again in October. Báez was overthrown by the Blue Party, but their allies turned on each other, and Cabral became president again in 1867.

In 1869, U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant sent U.S. Marines to the island for the first time to stop Dominican pirates. Báez then tried to get the United States to annex the Dominican Republic. This treaty was supported by U.S. Secretary of State William Seward. However, in 1871, the United States Senate rejected the treaty.

In 1874, there were more changes in power. In February 1876, Ulises Espaillat became president but was replaced by Báez ten months later. A new rebellion allowed Ignacio Maria González Santín to seize power, but he was removed by Cesáreo Guillermo in September 1878, who was then removed by Luperón in December 1879.

Luperón ruled from his hometown of Puerto Plata. The economy was booming due to more tobacco exports. He created a new constitution with a two-year presidential term and started building the nation's first railroad.

The Ten Years' War in Cuba brought Cuban sugar planters to the Dominican Republic. They built the nation's first mechanized sugar mills. Later, Italians, Germans, Puerto Ricans, and Americans joined them, forming the core of the Dominican sugar industry.

The Dominican Republic became a major sugar exporter. Sugar soon became the main export, surpassing tobacco. To transport sugar, over 300 miles of private rail lines were built by 1897. A drop in sugar prices in 1884 led to a labor shortage, which was filled by migrant workers from other Caribbean islands.

Ulises Heureaux and U.S. Influence

The dictatorship of General Ulises Heureaux, known as Lilís, brought stability to the island for almost two decades. Lilís was of Haitian and Virgin Islands descent. He served as President multiple times (1882–1883, 1887, and 1889–1899), often ruling through other presidents when not in office himself. He had a large network of spies to crush opposition. His government built important projects like electrifying Santo Domingo and starting telephone service. He also completed a railroad linking Santiago and Puerto Plata.

Lilís's rule depended on borrowing heavily from European and American banks. This money was used to enrich himself, pay off debt, strengthen his system of bribes, pay the army, and build infrastructure. However, sugar prices dropped sharply in the late 1800s. When a Dutch company went bankrupt in 1893, Lilís had to mortgage the nation's customs fees (the main source of government money) to a New York financial firm.

As the national debt grew, Lilís relied on secret loans. In 1897, with his government almost bankrupt, Lilís printed a lot of uninsured money, which ruined most Dominican merchants. This led to a plot that ended in his death. In 1899, when Lilís was assassinated, the national debt was over $35 million, which was 15 times the yearly budget.

The six years after Lilís's death saw four revolutions and five different presidents. The politicians who had plotted against Heureaux, Juan Isidro Jimenes and General Horacio Vásquez, quickly fell out.

In 1903, troops loyal to Vásquez overthrew Jimenes. But Vásquez was then removed by General Alejandro Woss y Gil. During a revolt, American warships bombarded parts of Santo Domingo.

With the country close to not being able to pay its debts, France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands sent warships to Santo Domingo to demand payment. To prevent military intervention, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt introduced the Roosevelt Corollary. This stated that the United States would make sure Latin American nations paid their financial debts.

In January 1905, the United States took control of the Dominican Republic's customs. A U.S.-appointed official kept 55% of the money to pay foreign creditors and sent 45% to the Dominican government. After two years, the country's foreign debt was greatly reduced. In 1907, the U.S. became the Dominican Republic's only foreign creditor. In 1905, the U.S. Dollar replaced the Dominican Peso.

In 1906, Morales resigned, and Ramón Cáceres became president. His government brought stability and economic growth, helped by new American investment in sugar.

However, his assassination in 1911 plunged the country into chaos again. A series of uprisings followed. In 1913, Vásquez returned from exile to lead a new rebellion. In June 1914, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson demanded that the two sides stop fighting and agree on a new president. After a temporary presidency, Jimenes was elected in October. He soon faced new demands from the U.S., including having American officers command a new military force. The Dominican Congress rejected these demands.

The United States occupied Haiti in July 1915. Jimenes's Minister of War, Desiderio Arias, staged a coup in April 1916. This gave the United States a reason to occupy the Dominican Republic.

United States Occupation: 1916–1924

| U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

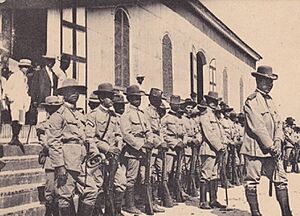

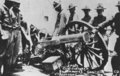

4th Marine Regiment with a captured rebel "spray gun" at Santiago. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,000 militia (1916) | 1,800 marines (1916) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 950 killed or wounded | 194 marines killed or wounded 247 sailors dead or injured |

||||||

U.S. Marines landed in Santo Domingo on May 5, 1916. Jimenes resigned, refusing to be president with "foreign bullets." On June 1, Marines occupied Monte Cristi and Puerto Plata. On June 26, Marines marched towards Arias's stronghold of Santiago. Dominicans tore up railroad tracks and burned bridges to slow them down. After some fighting, Arias surrendered on July 5.

Life Under Occupation

The Dominican Congress elected Dr. Francisco Henríquez y Carvajal as president. But in November, after he refused U.S. demands, President Wilson announced a U.S. military government. Rear Admiral Harry Shepard Knapp became the Military Governor.

The American military government made many changes. They reorganized the tax system, improved education, created a national police force to unite the country, and built a national road system.

The military government did not get support from Dominican political leaders. They put strict censorship laws in place and imprisoned critics. In 1920, U.S. authorities passed a Land Registration Act. This broke up shared lands and took land from thousands of peasants who didn't have formal titles. In the southeast, dispossessed peasants formed armed groups called gavilleros. They fought a guerrilla war for six years. The guerrillas knew the land well and had local support. The Marines had better weapons. However, rivalries among the gavilleros sometimes led them to fight each other or even help the occupation forces.

U.S. Marines and Dominican bandits clashed. To fight resistance, the United States created a local national guard called the Guardia Nacional Dominicana. The Marines and the Guardia pursued insurgents. The unrest in the eastern provinces lasted until 1922, when the guerrillas finally agreed to surrender in exchange for forgiveness. About 1,000 people, including 144 U.S. Marines, were killed during the conflict.

During World War I, sugar prices rose very high. Dominican sugar exports increased, bringing in a lot of money. However, European sugar production recovered quickly after the war, causing prices to drop sharply by the end of 1921. This crisis caused many local sugar planters to go bankrupt. Large U.S. companies then took over the sugar industry. As prices declined, sugar estates increasingly relied on Haitian workers.

U.S. Withdrawal

In the 1920 U.S. presidential election, Warren Harding criticized the occupation and promised to withdraw U.S. troops. The collapse of sugar prices made the military government unpopular. A new nationalist group, the Dominican National Union, demanded unconditional withdrawal. In May 1922, a Dominican lawyer, Francisco Peynado, negotiated a plan for U.S. withdrawal. On October 1, Juan Bautista Vicini was named temporary president, and the withdrawal began. U.S. forces left on September 18, 1924. The most important legacy of the occupation was the creation of a National Police Force. This force later became the main way Rafael Trujillo rose to power.

The Rise and Fall of Trujillo: The Third Republic (1924–1965)

Horacio Vásquez: 1924–1930

The U.S. occupation ended in 1924 with a democratically elected government under President Horacio Vásquez. His administration brought good social and economic times to the country. It also respected political and civil rights. Rising export prices and government borrowing helped fund public works projects and modernize Santo Domingo.

Vásquez extended his term from four to six years in 1927. This change was approved by Congress but was legally questionable. He also removed the rule against presidents being re-elected and planned to run again in 1930. However, his actions made people doubt if the election would be fair. Also, the Great Depression caused sugar prices to drop, leading to economic problems.

In February, a revolution started in Santiago led by Rafael Estrella Ureña. When the commander of the Guardia Nacional Dominicana, Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina, ordered his troops to stay in their barracks, the sick Vásquez was forced into exile. Estrella became temporary president. In May, Trujillo was elected with 95% of the vote. He used the army to bother and scare voters and opponents. After he became president in August, the Dominican Congress declared the start of the 'Era of Trujillo'.

The Era of Trujillo: 1931–1961

Trujillo gained complete political control. He promoted economic development, but mostly he and his supporters benefited. He also severely repressed human rights. Trujillo treated his political party, El Partido Dominicano, as a rubber stamp for his decisions. His real power came from the Guardia Nacional, which was bigger and better armed than any previous military force. By 1940, military spending was 21% of the national budget. He also created a complex system of spy agencies. By the late 1950s, there were at least seven types of intelligence agencies, spying on each other and the public. All citizens had to carry ID cards and good-conduct passes from the secret police.

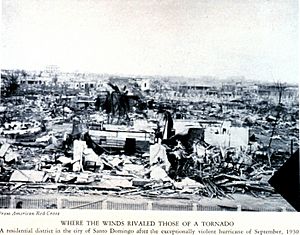

Trujillo loved to be praised. When a hurricane hit Santo Domingo in 1930, killing over 3,000 people, he rebuilt the city and renamed it Ciudad Trujillo ("Trujillo City"). He also renamed the country's highest mountain, Pico Duarte, to Pico Trujillo. Over 1,800 statues of Trujillo were built, and all public works had to have a plaque saying "Era of Trujillo, Benefactor of the Fatherland."

As sugar plantations used more Haitian seasonal workers, more Haitians settled permanently in the Dominican Republic. In 1920, there were 28,258 Haitians in the country; by 1935, there were 52,657.

In September 1937, Trujillo welcomed a Nazi group. The next month, Trujillo ordered the killing of an estimated 17,000 to 35,000 Haitians living near the border. This event became known as the Parsley Massacre. It's said that Dominican soldiers identified Haitians by their inability to say the Spanish word perejil.

The massacre was part of Trujillo's 'Dominicanisation of the frontier' policy. Place names along the border were changed to Spanish, and the practice of Voodoo was outlawed.

During the Holocaust in World War II, the Dominican Republic took in many Jewish refugees who had been turned away by other countries. These Jews settled in Sosua. This was part of a policy to increase the number of light-skinned people in the Dominican population by encouraging European immigration. In 1940, the U.S. gave up control over the nation's customs.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Trujillo joined the United States in declaring war on the Axis powers. Nazi submarines sank two Dominican merchant ships, killing 26 Dominican sailors. After the war, Trujillo wanted military aid from the U.S. but was denied. So, Trujillo built his own arms factory, making the Dominican Republic self-sufficient in small arms. In the 1950s, Trujillo's air force had 156 aircraft. His navy had two destroyers and eight frigates. During the Cold War, he stayed close to the United States, calling himself the world's "Number One Anticommunist."

Trujillo and his family gained almost complete control over the national economy. By the time he died, he had a fortune of about $800 million. He and his family owned 50–60% of the usable land. Trujillo's businesses accounted for 80% of the commercial activity in the capital.

World War II led to more demand for Dominican exports. The 1940s and early 1950s saw economic growth and expansion of national infrastructure. The capital city became a center of shipping and industry. However, mismanagement and corruption caused major economic problems by the late 1950s.

On June 14, 1959, Dominican exiles from Cuba tried to invade the Dominican Republic to overthrow Trujillo. Trujillo's forces quickly defeated them. The leaders of the invasion were thrown out of a plane in mid-air.

In August 1960, the Organization of American States (OAS) put diplomatic sanctions on the Dominican Republic. This was because Trujillo was involved in trying to kill Venezuelan president Rómulo Betancourt. The United States broke diplomatic relations on August 26, 1960, and stopped exporting trucks, oil, and other products in January 1961. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower also cut sugar purchases from the Dominican Republic. This cost the country a lot of money. Trujillo threatened to align with Communist countries in response. The U.S. government then turned to the Central Intelligence Agency to plan to kill Trujillo.

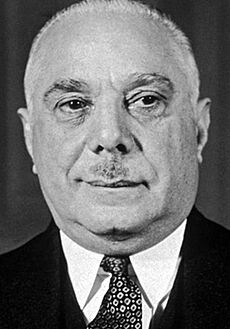

A group of Dominican opponents killed Trujillo in a car chase on May 30, 1961. The group was led by General Juan Tomás Díaz Quezada. Sanctions remained after Trujillo's death. His son Ramfis took charge and had the plotters executed. In November 1961, a military plot forced the Trujillo family into exile. The president, Joaquín Balaguer, then gained real power.

Post-Trujillo Instability: 1961–1965

The United States insisted that Balaguer share power with a seven-member Council of State, which included moderate opposition members. OAS sanctions were lifted on January 4, 1962. After an attempted coup, Balaguer resigned and went into exile on January 16. The new Council of State, led by President Rafael Filiberto Bonnelly, governed until elections could be held.

These elections, in December 1962, were won by Juan Bosch, a scholar and poet. He had founded the opposition Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD) while in exile. His policies, like land redistribution and trying to put the military under civilian control, angered military officers, the Catholic Church, and the upper class. They feared "another Cuba."

In September 1963, Bosch was overthrown by a right-wing military coup led by Colonel Elías Wessin. He was replaced by a three-man military government. Bosch went into exile in Puerto Rico.

Dominican Civil War and Second United States Occupation: 1965–1966

| Dominican Civil War Operation Power Pack |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Wounded American soldier in Santo Domingo, 1965. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

| Units involved | ||||||||

| Army | ||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

|

6,000 (mostly armed civilians) | 20,463 (plus 10,059 sailors offshore) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

|

|

216 killed or wounded in action | ||||||

On April 16, 1965, growing unhappiness led to another military rebellion on April 24, 1965. This rebellion demanded that Bosch be brought back. The rebels, called Constitutionalists, were officers and civilians loyal to Bosch, led by Colonel Francisco Caamaño. They took over the national palace. Immediately, conservative military forces, led by Wessin and called Loyalists, fought back with tanks and air bombings against Santo Domingo.

On April 28, the anti-Bosch army asked for U.S. military help. U.S. forces landed, supposedly to protect U.S. citizens and evacuate foreigners. U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, fearing "a second Cuba," ordered U.S. forces to restore order. In what was called Operation Power Pack, 27,677 U.S. troops were sent to the Dominican Republic.

The Constitutionalist rebels quickly had a congress elect Caamaño as president. U.S. officials supported General Antonio Imbert. On May 7, Imbert became president of the Government of National Reconstruction.

The American forces tried to block Radio Santo Domingo, which the rebels were using to broadcast messages. Imbert's forces captured Radio Santo Domingo and the northern part of the capital, destroying many buildings and killing many civilians. A cease-fire was agreed upon by May 21. By this time, 20 Americans had been killed and 102 wounded.

By mid-May, the Americans had created a "safety corridor" in Santo Domingo. This essentially sealed off the Constitutionalist area. Roadblocks were set up, and patrols ran constantly. About 6,500 people from many nations were safely evacuated. U.S. forces also brought in supplies for Dominicans.

By mid-May, the OAS voted to reduce U.S. forces and replace them with an Inter-American Peace Force (IAPF). This force was officially created on May 23. Brazil, Honduras, Paraguay, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and El Salvador sent troops. Brazilian General Hugo Panasco Alvim took command of the OAS ground forces. On May 26, U.S. forces began to withdraw.

Fighting continued until August 31, 1965, when a truce was declared. Most American troops left soon after, as policing and peacekeeping were handed over to Brazilian troops. However, some U.S. military presence remained until September 1966. A total of 48 American soldiers and marines died. Between 2,850 and 4,275 Dominicans, mostly civilians, were killed during the civil war.

The Fourth Republic: 1966–Present

Balaguer's Second Presidency: 1966–1978

In June 1966, Joaquín Balaguer, leader of the Reformist Party, was elected president. He was re-elected in May 1970 and May 1974. Both times, major opposition parties withdrew from the campaign because of violence from pro-government groups. On November 28, 1966, a new constitution was created. It stated that the president was elected for a four-year term. The voting age was 18, but married people under 18 could also vote.

Balaguer was seen by some as a caudillo who led a harsh government. However, he also made major reforms. During his time as president, the country saw big changes like legalizing political activities, surprising army promotions and demotions, improving health and education, and making small land reforms.

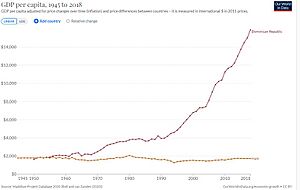

Balaguer led the Dominican Republic through a big economic change. He opened the country to foreign investment but also protected state-owned industries. This led to high economic growth rates, sometimes called the "Dominican miracle." Foreign investment and aid flowed into the country. Sugar, the main export, had good prices, and tourism grew a lot. Balaguer also gave land to peasants as part of his land reform policies.

However, this economic success did not mean wealth was shared equally. While some new millionaires became rich, some poor people became even poorer. The poor were often targeted by state security, and their demands were labeled "communist." In the May 1978 election, Balaguer was defeated by Antonio Guzmán Fernández of the PRD. Balaguer then ordered troops to destroy ballot boxes and declared himself the winner. U.S. President Jimmy Carter refused to recognize Balaguer's claim. Faced with losing foreign aid, Balaguer stepped down.

Guzmán / Blanco Interregnum: 1978–1986

Guzmán's inauguration on August 16 marked the country's first peaceful transfer of power from one freely elected president to another.

Hurricane David hit the Dominican Republic in August 1979, causing over $1 billion in damage.

By the late 1970s, economic growth slowed as sugar prices dropped and oil prices rose. Rising inflation and unemployment made people unhappy with the government. This led to many Dominicans moving to New York.

Guzmán died on July 5, 1982, a month before he was to leave office. Elections were held again in 1982. Salvador Jorge Blanco of the Dominican Revolutionary Party won.

Balaguer's Third Presidency: 1986–1996

Balaguer returned to power in 1986, winning the presidency again. He stayed in office for the next ten years. The 1990 elections had violence and suspected fraud. The 1994 election also saw widespread violence aimed at scaring opposition members. Balaguer won in 1994, but most observers felt the election was stolen. Under pressure from the United States, Balaguer agreed to hold new elections in 1996 and would not run himself.

Fernández: First Administration: 1996–2000

In 1996, Leonel Fernández Reyna, who grew up in the U.S., won more than 51% of the vote. He was from Bosch's Dominican Liberation Party (PLD) and formed an alliance with Balaguer. His first goal was to sell off some state-owned businesses. Fernández was praised for improving ties with other Caribbean countries. However, he was criticized for not fighting corruption or helping the 60% of the population living in poverty.

Mejía's Administration: 2000–2004

In May 2000, Hipólito Mejía of the PRD was elected president. People were unhappy about power outages in the recently privatized electric industry. His presidency saw major inflation and instability of the peso in 2003. This was due to the bankruptcy of three major banks because of bad policies. During his remaining time, he worked to save most savers of the closed banks, avoiding a bigger crisis. The peso's value dropped significantly against the U.S. dollar. In the May 2004 presidential elections, he was defeated by former president Leonel Fernández.

Fernández: Second Administration: 2004–2012

Fernández put in place measures to control the peso and help the country recover from its economic crisis. In the first half of 2006, the economy grew by 11.7%.

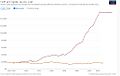

Over the last three decades, money sent home by Dominicans living abroad, mostly in the United States, has become very important to the economy. From 1990 to 2000, the Dominican population in the U.S. doubled. More than half of all Dominican Americans live in New York City. The New York metropolitan area now has more Dominicans than any city except Santo Domingo. Dominican communities have also grown in New Jersey, Miami, Boston, and other cities. Many Dominicans also live in Puerto Rico. Dominicans living abroad sent an estimated $3 billion in remittances to relatives at home in 2006. In 1997, a new law allowed Dominicans living abroad to keep their citizenship and vote in presidential elections. President Fernández, who grew up in New York, benefited greatly from this law.

The Dominican Republic was part of the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq. But in 2004, the nation pulled its troops out of Iraq.

Danilo Medina's Administration: 2012–2020

Danilo Medina began his term with some controversial tax reforms. These were to deal with the government's difficult financial situation. In 2012, he had won the presidency as the candidate of the ruling Dominican Liberation Party (PLD).

In 2016, President Medina won re-election. He defeated the main opposition candidate, businessman Luis Abinader, by a large margin.

Luis Abinader: 2020–Present

In 2020, Luis Abinader, the presidential candidate for the opposition Modern Revolutionary Party (PRM), won the election. He became the new president, ending the 16-year rule of the PLD since 2004.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la República Dominicana para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la República Dominicana para niños

- History of Haiti

- History of Latin America

- History of North America

- History of the Americas

- History of the Caribbean

- List of presidents of the Dominican Republic

- Politics of the Dominican Republic

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Timeline of Santo Domingo (city)

Images for kids

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |