Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse

|

|

|---|---|

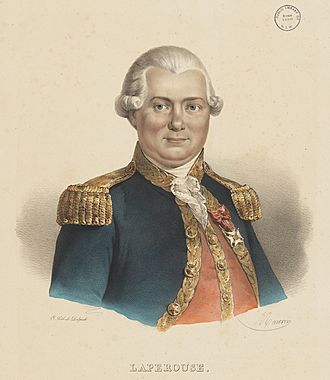

La Pérouse, with the Order of Saint Louis, 1778, by Geneviève Brossard de Beaulieu

|

|

| Born | 23 August 1741 near Albi, France |

| Died | c. 1788 (aged 46–47) Vanikoro, Solomon Islands (unconfirmed) |

| Allegiance | France |

| Service/ |

French Navy |

| Years of service | 1756–1788 |

| Rank | Commodore

|

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Chevalier de Saint-Louis |

Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse (often called simply Lapérouse) was a French naval officer and explorer. He was born on August 23, 1741, and likely died in 1788. He joined the navy at 15 and had a successful career. In 1785, he was chosen to lead a scientific journey around the world. His ships visited many places like Chile, Hawaii, Alaska, California, Japan, Russia, and Australia. Sadly, his ships were wrecked on the reefs of Vanikoro in the Solomon Islands.

Contents

Jean-François de Galaup was born near Albi, France. His family was given a special noble title in 1558.

Lapérouse went to a Jesuit college. He joined the French Navy in 1756 as a young officer-in-training. In 1757, he sailed on the ship Célèbre to deliver supplies to the fort of Louisbourg in New France (now Canada). He went on another supply trip in 1758. This was during the early years of the Seven Years' War, and the fort was under attack. His ship had to take a long route around Newfoundland to avoid British ships.

In 1759, Lapérouse was hurt in the Battle of Quiberon Bay. He was captured and held prisoner for a short time before being sent back to France. In 1762, he helped the French try to take control of Newfoundland. He escaped with his fleet when the British arrived with many ships.

When the American Revolutionary War started in 1778, Lapérouse was given command of the frigate Amazone. In 1779, he captured a British ship called HMS Ariel. Lapérouse was promoted to Captain in 1780. He sailed with a French fleet from Brest to America.

Later, Lapérouse took command of another frigate, Astrée. In 1781, he was asked to command a larger ship, but his crew was sick with scurvy. So, he asked to keep Astrée and was put in charge of a group of frigates.

In 1782, he helped attack St. Kitts and fought in the Battle of the Saintes. In August 1782, he became famous for capturing two English forts, Prince of Wales Fort and York Fort, on the coast of Hudson Bay. He allowed the survivors to sail to England in exchange for French prisoners. The next year, he married Louise-Eléonore Broudou, a young woman he had met eight years earlier.

Scientific Journey Around the World

In 1785, King Louis XVI and his Navy Secretary chose Lapérouse to lead an expedition around the world. Many countries were sending out scientific voyages at this time.

The King wanted Lapérouse to finish the discoveries made by James Cook in the Pacific Ocean. Lapérouse greatly admired Cook. The goals were to correct and complete maps, find new trade routes, and add to France's scientific knowledge. His two ships were L'Astrolabe and La Boussole, both 500 tons. They were supply ships that were changed into frigates for the journey.

The expedition aimed to explore the North and South Pacific, including the coasts of Asia and Australia. They also looked for chances to trade for things like whale oil or furs. They hoped to find places where France could set up bases or work with their Spanish allies. They were supposed to send back reports through European outposts in the Pacific.

Getting Ready for the Journey

In March 1785, Lapérouse suggested that Paul Monneron, the expedition's chief engineer, go to London. Monneron was to learn about how to prevent scurvy, a disease common on long sea voyages. He also bought scientific tools from English companies, including special compasses that had belonged to Captain Cook.

The Crew

Lapérouse was well-liked by his crew. There were ten scientists on board: an astronomer, a geologist, a botanist, a physicist, three naturalists, and three illustrators. Even the two chaplains had scientific training.

A young 16-year-old named Napoléon Bonaparte wanted to join the voyage. He was on the first list of possible crew members but was not chosen. At that time, Bonaparte was interested in serving in the navy because he was good at math and artillery, which were useful skills on warships.

The scientists used special clocks called marine chronometers and other tools to figure out their exact location and create accurate maps. Lapérouse showed how good Cook's methods were for mapping. Even though there was often fog on the northwest coast of America, he still managed to fill in some missing parts of the maps.

Stops in Chile and Hawaii

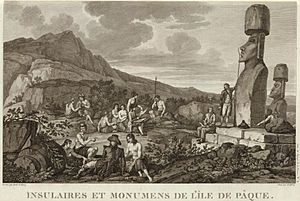

Lapérouse and his 220 men left Brest on August 1, 1785. They sailed around Cape Horn and then visited the Spanish government in Chile. On April 9, 1786, they arrived at Easter Island.

Next, they sailed to the Sandwich Islands, which are now the Hawaiian Islands. Lapérouse was the first European to step foot on the island of Maui.

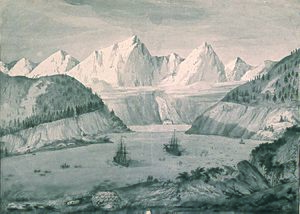

Exploring Alaska

Lapérouse continued to Alaska. He landed near Mount Saint Elias in late June 1786 and explored the area. On July 13, 1786, a small boat and two longboats, carrying 21 men, were lost in the strong currents of a bay. Lapérouse named it Port des Français, but it is now known as Lituya Bay. The men met the Tlingit people there. After this, he sailed south, exploring the northwest coast, including islands in what is now British Columbia.

Visiting California

From August 10 to 30, Lapérouse sailed south to the Spanish province of California. He stopped at the Presidio of San Francisco and made a map of the Bay Area. He arrived in Monterey Bay on September 14, 1786. He looked at the Spanish settlements, farms, and missions.

Lapérouse wrote about how the Franciscan missionaries treated the Indigenous peoples of California. He compared the conditions at a mission to a slave plantation. France and Spain were friendly at this time. Lapérouse was the first non-Spanish visitor to California since Francis Drake in 1579. He was also the first to visit after the Spanish missions and military forts were built.

East Asia, Japan, and Russia

Lapérouse crossed the Pacific Ocean again in 100 days, reaching Macau. There, he sold the furs he had gotten in Alaska and shared the money with his crew. In April 1787, after visiting Manila, he sailed to the northeast Asian coasts. He saw Quelpart Island (now Jeju-do in South Korea), which only a few Europeans had visited before. He also visited the Asian mainland coasts of Korea.

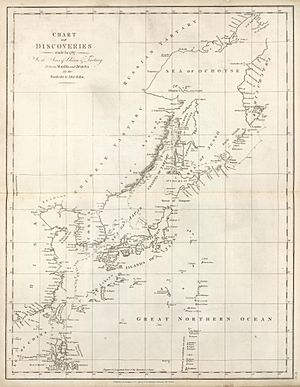

Lapérouse then sailed north to Oku-Yeso Island, which is now Sakhalin Island, Russia. The Ainu people who lived there drew him a map showing their islands and the coasts of mainland Asia. Lapérouse tried to sail through the narrow Strait of Tartary but couldn't. Instead, he turned south and then sailed east through La Pérouse Strait, between Sakhalin and Hokkaidō, where he met more Ainu people.

Lapérouse then sailed north again and reached Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky on the Russian Kamchatka Peninsula on September 7, 1787. They rested there and enjoyed the kindness of the Russians and local people. In letters from Paris, Lapérouse was told to check on the British settlement being built in New South Wales, Australia. A member of the expedition, Barthélemy de Lesseps, left the ships in Petropavlovsk. He carried the expedition's logs, maps, and letters back to France. He made a long journey across Siberia and Russia, reaching France a year later.

South Pacific Journey

Lapérouse's next stop was in the Navigator Islands (Samoa) on December 6, 1787. Just before they left, the Samoans attacked a group of his men. Twelve men were killed, including Lamanon (a geologist) and de Langle, the commander of L'Astrolabe. Twenty men were wounded. The expedition then went to Tonga for supplies and help.

Arrival in Australia

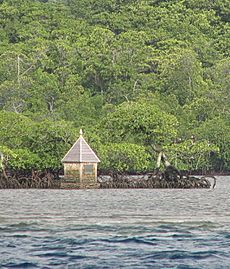

The expedition continued to Australia, arriving at Botany Bay on January 24, 1788. There, Lapérouse met a British fleet, known as the "First Fleet", led by Captain Arthur Phillip. Phillip was there to start a new penal colony (a place where prisoners are sent) called New South Wales. The British had planned to settle at Botany Bay, but Phillip quickly decided it wasn't suitable. He moved the colony to Sydney Cove in Port Jackson on January 26 (now Australia Day).

The French were welcomed kindly and stayed at the British colony for six weeks. This was their last recorded stop. Lapérouse and Phillip did not meet, but French and British officers visited each other many times. They offered each other help and supplies. The senior French officer, Robert Sutton de Clonard, who commanded L'Astrolabe, visited Governor Phillip. He gave Phillip dispatches to send to the French ambassador in London.

During their stay, the French set up an observatory and a garden. They also made observations about the land. Lapérouse used this chance to send journals, maps, and letters back to Europe. He sent them with the British ship Alexander, which was part of the First Fleet. The chaplain from L'Astrolabe, Father Louis Receveur, died at Botany Bay on February 17 from injuries he got in a fight with local people in Samoa. He was buried on shore at Frenchman's Cove.

On March 10, after getting enough wood and fresh water, the French expedition left New South Wales. They planned to sail to New Caledonia, the Santa Cruz Islands, the Solomon Islands, and the western and southern coasts of Australia. Lapérouse had written that he expected to be back in France by June 1789. However, no one from his expedition was ever seen by Europeans again.

It is said that King Louis XVI asked, on the morning of his execution in January 1793, "Any news of La Pérouse?"

The documents sent back by Lapérouse's expedition were published in Paris in 1797. In 1825, a French naval officer, Captain Hyacinthe de Bougainville, built the Lapérouse Monument near Receveur's grave. The area later became part of the suburb of La Perouse.

What Happened to Lapérouse?

The Search for Lapérouse

On September 25, 1791, Rear Admiral Bruni d'Entrecasteaux left Brest to search for Lapérouse. His expedition followed Lapérouse's planned route through the islands northwest of Australia. They also made their own scientific discoveries. His expedition had two ships, Recherche and Espérance.

In May 1793, Entrecasteaux saw Santa Cruz and another island nearby that wasn't on maps. This island was Vanikoro. The French ships didn't go close to Vanikoro. They just marked it on their maps and sailed on to explore more of the Solomon Islands. Two months later, Entrecasteaux died. A botanist on the expedition, Jacques Labillardière, later returned to France and published his story in 1800.

Rumors spread in France that the British were to blame for the disaster near the new British colony. Before the mystery was solved, the French government published the records of Lapérouse's voyage up to Kamchatka. These books are still used for maps and scientific information about the Pacific.

Discovery of the Expedition's Fate

In 1825, a British naval captain, Thomas Manby, reported that he believed he knew where Lapérouse and his crew had died. An English whaling ship found a low island with many reefs between New Caledonia and New Guinea. The people from the island came onto the whaler. One chief had a cross of St. Louis (a French award) hanging from his ear. Other natives had swords with the word 'Paris' on them. Some had medals of King Louis XVI. One chief, about fifty years old, said that when he was young, a large ship was wrecked on a coral reef during a strong storm. Manby had seen similar medals that Lapérouse had given to people in California.

It wasn't until 1826 that an Irish sea captain, Peter Dillon, found enough clues to figure out what happened. In Tikopia (one of the Santa Cruz islands), he bought some swords that he thought belonged to Lapérouse or his officers. He asked around and found out they came from nearby Vanikoro. People there said two big ships had broken up years ago. Dillon managed to get a ship and sailed to Vanikoro. There, he found cannonballs, anchors, and other ship remains in the water among the coral reefs.

Dillon brought some of these items back to Europe. Another explorer, Jules Dumont d'Urville, also brought items back in 1828. Lesseps, the only member of the original expedition still alive, said they all belonged to L'Astrolabe. From what the people of Vanikoro told Dillon, a rough idea of the disaster could be made. Dillon's findings were later confirmed in 1964 when what was believed to be the shipwreck of Boussole was found and examined.

Modern Expeditions

In May 2005, the shipwreck found in 1964 was officially identified as Boussole. A French Navy ship, Jacques Cartier, carried a team of scientists to investigate the "Mystery of Lapérouse." This mission was called "Operation Vanikoro—Tracing the Lapérouse wrecks 2005."

Another similar mission took place in 2008. This expedition showed France's dedication to finding more answers about Lapérouse's fate. It had support from the French President and various government ministries. This eighth expedition to Vanikoro used more technology than before. It involved two ships, 52 crew members, and almost 30 scientists. They arrived at Vanikoro on October 15, 2008, following a part of Lapérouse's last voyage.

The Final Fate

Both of Lapérouse's ships were wrecked on Vanikoro's reefs. Boussole was wrecked first. L'Astrolabe was unloaded and taken apart. A group of men, probably the survivors from Boussole, were killed by the local people. According to the islanders, some surviving sailors built a new two-masted boat from the wreckage of L'Astrolabe. They left in a westward direction about nine months later, but no one knows what happened to them. Also, two men, a "chief" and his servant, stayed behind but left Vanikoro a few years before Dillon arrived.

Some historians believe there was a chance to rescue survivors in 1791. In November 1790, Captain Edward Edwards of HMS Pandora was searching the Pacific for the mutineers from HMS Bounty. In March 1791, Pandora arrived at Tahiti and picked up 14 Bounty crewmen. They were imprisoned in a small "cage" on deck.

When Pandora passed Vanikoro on August 13, 1791, Captain Edwards saw smoke signals rising from the island. However, he was focused on finding the Bounty mutineers. He thought that mutineers wouldn't be signaling their location, so he ignored the smoke and sailed on.

Some people argue that these smoke signals were almost certainly a distress message from Lapérouse's survivors. Evidence suggests they were still alive on Vanikoro at that time, three years after their ships sank. They believe Captain Edwards missed his chance to solve the mystery of the lost Lapérouse expedition.

Legacy and Memorials

Museum Collections

Items related to Lapérouse's life and voyages are kept at The Lapérouse Museum in Albi, France, and the Maritime Museum of New Caledonia. Both museums have objects found from the ships Astrolabe and Boussole. There is also a Lapérouse Museum in La Perouse, Australia, which tells about his time there.

Places Named After Lapérouse

Many places have been named to honor Lapérouse:

- Mount La Perouse (3231 m) and La Perouse Glacier in Alaska.

- Mount La Pérouse (1127 m) on Haida Gwaii, British Columbia.

- La Pérouse Reef off the west coast of Haida Gwaii, British Columbia.

- La Perouse Bank, west of Vancouver Island.

- La Perouse Strait between Hokkaidō (Japan) and Sakhalin (Russia).

- Mount La Perouse (1157 m) and the La Perouse Range in Tasmania, Australia.

- La Perouse Pinnacle (37 m), in the French Frigate Shoals, Hawaii.

- La Perouse (New Zealand) (3078 m), in New Zealand's Southern Alps.

- La Perouse Glacier, Westland, New Zealand.

- La Perouse Bay, where he landed on Maui (Hawaii).

- La Perouse Bay (Easter Island).

- La Perouse, a suburb of Sydney, Australia.

- La Perouse Street, a main street in Griffith, Canberra, Australia. There is a statue of La Perouse there.

- La Pérouse (crater), a crater on the Moon.

- Rue La Pérouse, a street in Paris, France.

Ships Named After Lapérouse

- Several ships in the French navy have been named after him.

- CMA CGM Laperouse, a large container ship.

- Le Lapérouse, a cruise ship.

Lapérouse in Books and Movies

The story of Lapérouse's fate is a chapter in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne. He was also mentioned in an episode of the TV series Northern Exposure.

The novel Landfalls by Naomi J. Williams tells the story of the Lapérouse expedition in detail.

Henry David Thoreau mentions him in his book Walden. He talks about the "untold fate of La Perouse" when discussing the importance of careful planning and navigation.

Jon Appleton wrote an opera about Lapérouse's last voyage, called Le Dernier Voyage de Jean-Gallup de la Perouse.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jean-François de La Pérouse para niños

In Spanish: Jean-François de La Pérouse para niños