Johnson Creek (Willamette River tributary) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Johnson Creek |

|

|---|---|

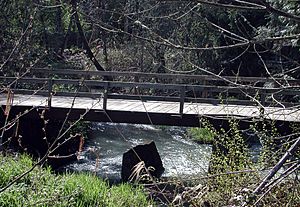

Johnson Creek near Regner Road in Gresham

|

|

Johnson Creek watershed

|

|

|

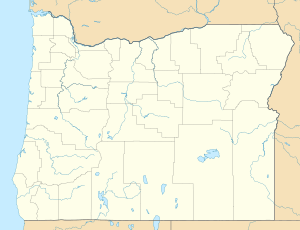

Location of the mouth of Johnson Creek in Oregon

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Clackamas and Multnomah |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Cascade Range foothills near Cottrell, Clackamas County, Oregon 745 ft (227 m) Elevation derived from Google Earth search using GNIS source coordinates 45°26′51″N 122°17′18″W / 45.4476206°N 122.2884222°W |

| River mouth | Willamette River Milwaukie, Clackamas County, Oregon 26 ft (7.9 m) 45°26′39″N 122°38′36″W / 45.4442860°N 122.6434273°W |

| Length | 25 mi (40 km) |

| Discharge (location 2) |

|

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 54 sq mi (140 km2) |

Johnson Creek is a 25-mile (40 km) long stream in Oregon. It flows into the Willamette River near Portland. The creek is part of the larger Columbia River system. Its watershed covers about 54 square miles (140 km2). Around 180,000 people live in this area.

Johnson Creek flows west from the Cascade Range foothills. It passes through the cities of Gresham, Portland, and Milwaukie. Even though the creek has some water pollution, it flows freely. It provides a home for salmon and other migrating fish.

Before European settlers arrived, Native Americans like the Chinook people lived here. They used the land for fishing and hunting. In the 1800s, settlers cleared much of the land for farming. The creek is named after William Johnson, who built a sawmill along it in 1846. Later, a train line was built next to the creek. This helped more homes and businesses grow.

As more people moved into the floodplain, seasonal floods became more damaging. In the 1930s, the U.S. government tried to control floods. They lined about 15 miles (24 km) of the creek with rock. But the creek still flooded 37 times between 1941 and 2006. Since the 1990s, local groups have worked to reduce flooding. They also try to improve the creek's health.

The Johnson Creek watershed includes smaller streams. These include Badger Creek, Sunshine Creek, and Crystal Springs Creek. Parks along the creek offer natural areas and gardens. There is also a 21-mile (34 km) rail trail for biking and walking.

Contents

Creek's Journey

Johnson Creek starts in the foothills of the Cascade Range. This is near a small place called Cottrell in Clackamas County, Oregon. It flows west for about 25 miles (40 km). The creek ends when it joins the Willamette River. The Willamette River then flows into the Columbia River.

The creek flows through Gresham, Portland, and Milwaukie. It crosses the border between Clackamas County and Multnomah County eight times.

For most of its journey, Johnson Creek flows across the numbered streets of southeast Portland. As the creek goes downhill, the street numbers get lower. The creek starts in the hills east of Southeast 362nd Avenue. It flows quickly west for about 5 miles (8 km). It crosses the county border five times in this area. It also goes under U.S. Route 26. Soon after, smaller streams like Badger Creek and Sunshine Creek join it.

Johnson Creek then turns sharply and flows northwest for about 3 miles (5 km). It enters Gresham and passes a measuring station at Regner Road. This station is about 16.2 miles (26.1 km) from where the creek ends. Soon, the creek enters Main City Park in Gresham. Here, it turns again and flows slowly west. The land becomes flatter, and the creek moves slower for the next part of its journey.

West of Main City Park, the creek passes the Gresham Pioneer Cemetery. It then enters Portland about 13 miles (21 km) from its mouth. Kelley Creek, another stream, joins Johnson Creek here. Johnson Creek then passes another measuring station at Sycamore. This station is 10.2 miles (16.4 km) from the mouth. The creek also flows under Cedar Crossing Bridge.

The creek winds slowly through the Lents neighborhood of Portland. Veterans Creek joins it from Happy Valley. Johnson Creek then goes under Interstate 205. It starts flowing faster again near Southeast 82nd Avenue, about 8 miles (13 km) from its mouth. It briefly dips into Clackamas County and then back into Multnomah County. It then flows near the border of Portland and Milwaukie for about 2 miles (3 km).

After passing under Oregon Route 99E in Portland's Sellwood neighborhood, the creek turns south. This is about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from its end. At Southeast 21st Avenue, Crystal Springs Creek joins it. This stream is 2.7 miles (4.3 km) long. It starts at Reed College, flows through the Crystal Springs Rhododendron Garden, and then joins Johnson Creek.

From this point, Johnson Creek flows south for about 1 mile (1.6 km). It crosses the county border one last time. After re-entering Clackamas County, it passes a measuring station in Milwaukie. This is 0.7 miles (1.1 km) from its mouth. Finally, Johnson Creek flows into the Willamette River. The Willamette River then flows about 100 miles (160 km) to the Pacific Ocean.

Creek's Land Area

Land Features

The flat areas around Johnson Creek were formed by huge Missoula Floods long ago. These floods deposited thick layers of sediment (dirt and rocks). Underneath these layers are hard basalt rocks. These rocks are mostly seen in the higher areas. They have been shaped by faults to create the Johnson Creek watershed.

The watershed is a rectangle shape, about 54 square miles (140 km2). The land changes a lot in height. It goes from about 1,100 feet (340 m) above sea level near the creek's start to 26 feet (7.9 m) where it meets the Willamette River.

The slopes in the watershed are usually between 1 and 25 percent. Mount Scott and Powell Butte are about 1,000 feet (300 m high). They have steeper slopes, from 10 to 30 percent. Gresham Butte and Hogan Butte in Gresham have the steepest slopes, some around 50 percent.

The eastern part of the watershed is more open and rural. The western part is more urban, with many homes, businesses, and factories. About 180,000 people lived in the watershed in 2012.

Soil and Water

The risk of erosion (soil washing away) changes across the watershed. In the flat, developed northwest, erosion is not a big problem. In the southeast, the soil has a medium risk of erosion. Around Powell Butte, the soil can erode very easily.

The soils also differ in how much water they can absorb. Clay soils, which don't absorb much water, are common in the eastern part and south of the creek. Areas to the north tend to have porous soils that absorb water better.

The watershed has two main areas for how water soaks into the ground. The northern area (about 40 percent of the watershed) has soils that let most rain soak in. The southern area has soils where most rain runs quickly into the creek. Rain that soaks into the ground in the north helps keep the creek flowing during dry times.

About 40 percent of the small streams that used to flow on the surface were put into pipes or moved during city growth. Most of the streams that still flow freely start south of Johnson Creek and run north. A main exception is Crystal Springs Creek, which starts from groundwater (water underground) and flows south.

Who Manages the Creek?

Six different local governments manage parts of the Johnson Creek watershed. In 2000, 38 percent of the watershed was in Portland. Other parts were in Clackamas County (24 percent), Gresham (23 percent), Multnomah County (11 percent), Milwaukie (4 percent), and Happy Valley (0.1 percent). No single city is entirely within the watershed.

A group called the Johnson Creek Watershed Council (JCWC) was formed in 1995. This nonprofit group works to protect the creek and its land. They remove invasive species (plants that don't belong). They also plant native plants along the creek. They help fish move more easily by removing barriers. Many volunteers help with these projects. In 2011, over a thousand volunteers gave 5,500 hours of their time.

Creek's Health Report

Since 2015, Portland's Bureau of Environmental Services (BES) gives "report cards" for watersheds. They grade the creek's health in four areas:

- Hydrology: How much pavement is in the area and how freely the streams flow.

- Water Quality: Measures of oxygen, bacteria, temperature, and chemicals in the water.

- Habitat: The condition of the creek banks, floodplains, and trees.

- Fish and Wildlife: The health of birds, fish, and small water insects.

In 2015, Johnson Creek got these grades: Hydrology, B+; Water Quality, C+; Habitat, C; and Fish and Wildlife, D+.

Creek's Past

Before settlers arrived, the Johnson Creek area was covered with forests and wetlands. Native Americans lived here. They fished, hunted, and gathered food. People may have lived in the northern Oregon Cascade Range as early as 10,000 years ago.

The Clackamas people, a group of Chinookan speakers, lived in this area. Their land included the lower Willamette River and parts of the Cascade foothills. When Lewis and Clark visited in 1806, about 1,800 Clackamas people lived in 11 villages. But diseases like smallpox and malaria greatly reduced their population. By 1851, only 88 Clackamas people remained. In 1855, the tribe signed a treaty and gave up their lands, including Johnson Creek.

By the mid-1800s, European American settlers began to clear land. They built sawmills, cut down trees, filled wetlands, and farmed the rich soil. The creek is named after William Johnson. He settled in the Lents neighborhood of Portland in 1846 and ran a sawmill. In 1886, plans were made for train tracks along the creek. The Springwater Division Line was built in 1903. This train line carried people and goods. New communities like Sellwood and Lents grew along the line. By the 1920s, houses started to replace farms along the creek.

Flooding Challenges

When people developed the land around Johnson Creek, they removed natural plants. This caused rainwater to run off faster, leading to more damaging floods. In the 1930s, the U.S. government tried to control these floods. They cleared and lined about 15 miles (24 km) of the creek with rock. This created an artificial channel. Even with this, the creek still overflowed. The biggest flood in 1964 damaged 1,200 buildings.

Johnson Creek often floods between November and February. This is because Portland gets a lot of rain during these months. The lower parts of the creek get about 36 inches (910 mm) of rain each year. The higher parts of the watershed get much more, over 70 inches (1,800 mm).

Floods mainly affect four areas in Portland. These include Tideman Johnson Natural Area and the Lents neighborhood. The U.S. National Weather Service says Johnson Creek is flooding when its water level reaches 11 feet (3.4 m). This means about 1,200 cubic feet (34 m3) of water flows per second. Between 1941 and 2006, the creek flooded 37 times. Twenty of these floods were very large. At least seven caused major property damage. In December 2007, the creek rose 1.5 feet (0.46 m) above flood stage.

The biggest flood measured at Sycamore (10.2 miles or 16.4 km from the mouth) happened in 2015. The creek reached 15.33 feet (4.67 m) on December 7. The second highest was in November 1996, at 15.30 feet (4.66 m). The Christmas flood of 1964 reached 14.68 feet (4.47 m).

In the 1970s and 1980s, there were plans to control Johnson Creek floods. But local residents disagreed with these plans. In 1990, the City of Portland formed the Johnson Creek Corridor Committee. This group included different agencies and citizens. In 2001, they created the Johnson Creek Restoration Plan. This plan aims to reduce flooding, improve water quality, and help fish and wildlife.

Projects include controlling stormwater runoff and reducing erosion. They also replace hard surfaces with natural ones. They protect the riparian zones (areas along the creek). By 2007, at least 75 restoration projects had been done. Many involved volunteers. In 2012, the city finished the East Lents Floodplain Project. This project restored 70 acres (28 ha) of natural floodplain.

Water Pollution

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) rated Johnson Creek's water quality as "very poor" between 1986 and 1995. They found high levels of nitrates and phosphates. Also, coliform bacteria, solids, and other substances hurt the water quality. These problems happened all year.

The DEQ uses an index where 10 is the worst and 100 is ideal. Johnson Creek's lowest average score was 26. This was the second worst in the lower Willamette basin. Most of the pollution in Johnson Creek comes from surface runoff during storms. It washes off urban and rural land.

High water temperatures are also a problem for water animals. Salmon need cool water, usually below 17.8 °C (64.0 °F). But Johnson Creek's summer temperatures are often higher than this. The highest temperature salmon can survive for a short time is 24 °C (75 °F). In 1992, Johnson Creek reached this temperature.

Studies have found harmful chemicals in Johnson Creek. These include DDT, dieldrin, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and chlordane. The creek also has high levels of copper, chromium, and nickel. These metal levels usually increase further downstream.

Creek Life: Plants and Animals

Water Animals and Fish

A 1999 study found that Johnson Creek had poor conditions for macroinvertebrates. These are small water insects and creatures. They are an important food source for fish. The study compared Johnson Creek to healthier rural streams. It found that the small bottom-dwelling creatures in Johnson Creek were not as healthy.

Most fish species in Johnson Creek can handle warm water and disturbed conditions. These include shiners, sculpin, suckers, and speckled dace.

Before cities grew, many salmon lived in the creek. Today, smaller numbers of Chinook and coho salmon, steelhead, and coastal cutthroat trout still live there. Steelhead and salmon in Johnson Creek are listed as "threatened" species. This means their populations are at risk.

Wildlife Around the Creek

In the past, large animals like bobcats, black bears, foxes, cougars, and elk lived here. Today, common animals include crows, robins, starlings, song sparrows, raccoons, opossums, and nutria.

Less developed areas have black-tailed deer and coyotes. Other wildlife in the watershed includes beavers, river otters, freshwater mussels, and bald eagles.

Some animals in the Johnson Creek watershed are listed as "sensitive" species in Oregon. This means they are native animals that might become threatened or endangered. These include different types of salamanders, red-legged frogs, painted turtles, and great horned owls. A plant called tall bugbane found on Powell Butte is also a sensitive species.

Plants Along the Creek

The Johnson Creek area is part of the Willamette Valley ecoregion. Before the mid-1800s, it had forests of Oregon ash, red alder, and western redcedar. There were also black cottonwood trees along the creek. Douglas fir and Oregon white oak grew in the higher areas.

About 57 percent of the watershed is covered with plants. As of 2000, about 70 percent of the watershed was within the city's growth area. Most of the land (57 percent) has single-family homes. Parks and open spaces make up 13 percent.

Creek restoration projects have reduced Himalayan blackberry. This is an invasive species that took over much of the land near the creek. New plantings include native shrubs and trees. These are plants like red-osier dogwood, elderberry, and willow. City parks next to Johnson Creek have marsh areas, forested wetlands, and open meadows.

Parks and Trails

By 1960, the train line along Johnson Creek was used less often. Passenger service stopped. In 1990, the City of Portland bought much of the old train path. They worked with Metro to create the Springwater Corridor Trail. This is a 21-mile (34 km) bike and walking trail. It follows the creek and goes from the Willamette River to Boring. It is part of the 40-Mile Loop, a larger trail system around Portland.

Parks along the creek include:

- Johnson Creek Park: About 4.5 acres (1.8 ha) of natural areas and paths.

- Crystal Springs Rhododendron Garden: A beautiful garden along Crystal Springs Creek.

- Tideman Johnson Natural Area: About 7.2 acres (2.9 ha) of natural areas.

- Leach Botanical Garden: A public garden focused on plants of the Pacific Northwest. It is about 16 acres (6.5 ha).

- Beggars Tick Wildlife Refuge: A 20-acre (8.1 ha) wetland for wildlife.

- Powell Butte Nature Park: About 608 acres (246 ha) on an old volcano. It has natural areas and trails for hiking, biking, and horses.

- Gresham's Main City Park: About 18 acres (7.3 ha) with sports fields, picnic areas, and trails.

In 2007, Metro bought two pieces of land near Johnson Creek on Clatsop Butte. These lands total 102 acres (41 ha). They were bought to protect them. The cost was $10.9 million, using money from a public vote.

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |