Lewis Milestone facts for kids

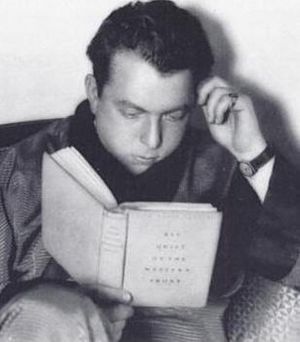

Lewis Milestone (born Leib Milstein; September 30, 1895 – September 25, 1980) was a famous American film director. He is best known for directing Two Arabian Knights (1927) and All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Both films earned him Academy Awards for Best Director. He also directed other important movies like The Front Page (1931), Of Mice and Men (1939), and Ocean's 11 (1960).

Contents

- Lewis Milestone's Early Life and Career Beginnings

- Becoming a Director: The Silent Film Era (1925–1929)

- Milestone's Early Sound Films (1929–1936)

- A Break from Directing (1936–1939)

- World War II Films (1942–1945)

- The Red Scare and Hollywood's Blacklist

- Post-War Films (1946–1951)

- Later Career (1952–1962)

- Television Work and Unfinished Projects (1955–1965)

- Milestone's Final Years

- Lewis Milestone's Film Legacy

- Lewis Milestone's Filmography

- See also

Lewis Milestone's Early Life and Career Beginnings

Milestone was born Lev (or Leib) Milstein in 1895, near the Black Sea port of Odessa, Ukraine, in what was then the Russian Empire. His family was wealthy.

In 1900, his family moved to Kishinev (now Chișinău, Moldova). Lewis went to Jewish schools where he learned several languages. His parents were very open-minded. Even though his family didn't want him to work in theater, Lewis loved it. They sent him to Mittweida, Germany, to study engineering.

However, Lewis spent his time watching plays instead of studying. He failed his classes. Determined to work in theater, he bought a one-way ticket to the United States. He arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey, in November 1913, just after his 18th birthday.

"You are in the land of liberty and labor, so use your own judgement."—His father's short reply from Russia when Lewis asked for money from New York City.

Lewis struggled to find work in New York City. He had many odd jobs, like a janitor and a salesman. In 1915, he found work as a portrait and theater photographer. In 1917, after America joined World War I, he joined the Signal Corps. He worked in the photography unit, helping with training films and editing war footage. Other future Hollywood directors, like Josef von Sternberg, worked with him there.

In 1919, Lewis left the army and became a U.S. citizen. He legally changed his last name from Milstein to Milestone. A friend from the Signal Corps helped him get an entry-level job in Hollywood as an assistant editor.

Learning the Ropes in Hollywood (1919–1924)

When Milestone arrived in Hollywood, he was still struggling financially. He even worked briefly as a card dealer to make money before his studio job started.

Despite some simple tasks, Milestone slowly moved from assistant editor to director. In 1920, he became a general assistant to director Henry King. His first credited work was as an assistant on King's 1920 film, Dice of Destiny.

For the next six years, Milestone took on many different jobs in the film industry. He worked as an editor for director-producer Thomas Ince. He also helped write film scripts and even wrote jokes for comedian Harold Lloyd. In 1923, he became an assistant director at Warner Brothers studios. He ended up doing most of the filmmaking tasks on Little Church Around the Corner (1923). Milestone became known as a "film doctor" because he was good at fixing movies. Warner Brothers even started offering his services to other studios.

Becoming a Director: The Silent Film Era (1925–1929)

By 1925, Milestone was writing many film ideas for Universal and Warner Brothers. These included The Mad Whirl and Bobbed Hair. That same year, Milestone made a deal with Jack Warner. He offered to give Warner a story for free if he could direct it. Warner agreed, and Milestone directed his first film, Seven Sinners (1925).

Seven Sinners (1925): This was one of three films Milestone directed with actress Marie Prevost. Darryl F. Zanuck wrote the script. It was a comedy with some slapstick humor. Seven Sinners was successful enough for Milestone, who was 29, to get more directing jobs.

The Caveman (1926): Milestone quickly directed his second comedy with Prevost, The Caveman. He was praised for his "skillful direction." However, during this film, Milestone broke his contract with the studio. Warner Brothers sued him and won, which forced Milestone to declare bankruptcy. The Caveman was his last film for Warners until 1943. But Milestone wasn't stopped; Paramount Pictures quickly hired him.

Two Arabian Knights (1927): This film is considered Milestone's best work during the silent era. It was inspired by a stage play and a film called What Price Glory?. This was the first film in a four-year contract with Howard Hughes's company. It earned Milestone an Academy Award for best comedy direction in 1927, beating Charlie Chaplin's The Circus. The story is set during World War I and features a funny love triangle.

The Garden of Eden (1927): This film was released through Universal Pictures. The Garden of Eden was a "Cinderella story" with a clever style. It benefited from amazing sets designed by William Cameron Menzies and great camera work. It starred the popular actress Corinne Griffith. These two films, Two Arabian Knights and The Garden of Eden, showed Milestone's skill in directing both rough and sophisticated comedies.

The Racket (1928): Milestone didn't want to be known only for comedies. So, he directed The Racket, a gangster film. This movie showed a police department controlled by mobsters. It was "tense and realistic" and proved Milestone could direct this type of film well. The Racket was nominated for Best Picture at the 1928 Academy Awards.

Milestone's Early Sound Films (1929–1936)

Transitioning to Sound with New York Nights (1929)

Milestone's first attempt at a sound film, New York Nights, was not very successful. It was made for silent film star Norma Talmadge. Milestone tried to mix "show-biz" and gangster stories, but the film wasn't well-received. One film historian said it was "not worth considering as Milestone's first sound work."

His Masterpiece: All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

Milestone's anti-war film All Quiet on the Western Front is seen as his greatest work. It's one of the most powerful movies about soldiers fighting in World War I. The film was based on Erich Maria Remarque's famous 1929 novel. Milestone brought the book's "grim realism and anti-war themes" to the screen. Universal Pictures bought the film rights because the book was so popular worldwide.

"When he was preparing to shoot his wrenching anti-war film All Quiet on the Western Front from the point of view of German schoolboys who become soldiers, Universal co-founder and president Carl Laemmle pleaded with him for a 'happy ending.' Milestone replied, 'I've got your happy ending. We'll let the Germans win the war.'

All Quiet on the Western Front shows the war from the viewpoint of young German soldiers. They start out patriotic but become very disappointed by the horrors of trench warfare. Actor Lew Ayres plays Paul Baumer, a young and sensitive soldier.

Milestone worked with screenwriters to create a script that captured the book's "tough dialogue." The goal was to "expose war for what it is, and not glorify it." Milestone filmed both a silent and a sound version at the same time.

One of the most impressive things about All Quiet on the Western Front was how Milestone used the new sound technology with the advanced visual effects from the silent film era. He recorded sound separately, which allowed him to "shoot the way we've always shot." In one powerful scene, Milestone uses moving camera shots and sound effects to show the terrible impact of artillery and machine guns on soldiers.

The movie was a huge success with critics and audiences. It won a Best Picture Oscar and Milestone won his second Best Director award.

All Quiet on the Western Front made Milestone a major talent in the film industry. Howard Hughes then gave him another important project: adapting the 1928 play The Front Page.

Directing The Front Page (1931)

The Front Page was a very exciting and influential film in 1931. It introduced the idea of the tough, fast-talking reporter in Hollywood movies. Milestone showed the busy world of Chicago newspaper offices. The film kept the "sparkling dialogue [and] hard, fast and ruthless pace" of the original play. The Front Page helped create a whole new "journalism genre" in the 1930s. Many other studios copied it, and it led to remakes like Howard Hawks' His Girl Friday (1940).

Milestone wanted James Cagney or Clark Gable to play the reporter "Hildy" Johnson. But producer Howard Hughes chose Pat O'Brien instead, who had been in the play.

Milestone added an Expressionistic film style to the movie. The opening camera shots of the newspaper's printing plant and a scene where a woman faces many reporters show Milestone's skill.

The Front Page was nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards. Milestone was also named one of "The Ten Best Directors" by a poll of 300 movie critics.

Milestone was worried that film directors were losing control in the studio system. He strongly supported King Vidor's idea to start a filmmakers' group. Many famous directors, like Howard Hawks and Ernst Lubitsch, supported this. By 1938, the Screen Directors Guild was formed, representing many directors.

Paramount Pictures faced money problems in the mid-1930s. This made it hard for them to support directors like Milestone. During this time, Milestone struggled to find good stories, production support, and the right actors. His first film during this period was Rain (1932).

Rain (1932): This film was based on a short story by Somerset Maugham. Milestone was given rising star Joan Crawford for this movie.

Hallelujah, I'm a Bum (1933): Released during the Great Depression, this film tried to bring back singer Al Jolson. It was based on a story by Ben Hecht and had songs by Rodgers and Hart. The movie was about a New York City tramp. However, audiences didn't like its sentimental theme. One historian noted that "Americans in the winter of 1933 were not in the mood to be advised that the life of a hobo was the road to true happiness." Milestone's attempt at a "socially conscious" musical was not well-received.

Milestone tried to make films about the Russian Revolution and an adaptation of H. G. Wells's The Shape of Things to Come, but neither happened. Instead, he made three "insignificant" studio films from 1934 to 1936.

The Captain Hates the Sea (1934): Milestone accepted a good offer to direct this film for Columbia Pictures. It was seen as a spoof of the star-studded 1932 film Grand Hotel. Milestone's film featured many character actors. It was described as "uneven" and "rambling." High costs and heavy drinking by the cast caused problems between Milestone and the studio head. This movie was the last film of actor John Gilbert's career.

Milestone then directed two musicals for Paramount, which he called "insignificant": Paris in Spring (1935) and Anything Goes (1936).

Paris in Spring (1935) and Anything Goes (1936): Paris in Spring was a romantic musical comedy. Milestone tried to make it rival other successful musicals. While the art directors created a believable Paris, Milestone's camera work couldn't overcome the "flatness of the tale." Anything Goes starred Bing Crosby and Ethel Merman and was based on a Cole Porter Broadway musical. It had some classic songs. Milestone did his job well, but he wasn't very excited about directing musicals.

In his personal life, Milestone had more success. In 1935, he married Kendall Lee Glaezner, an actress he met on the set of his 1932 film Rain. They stayed married until her death in 1978. They did not have children. The Milestones were known for hosting great parties in Hollywood.

The General Died at Dawn (1936)

After his two less successful musicals, Milestone returned to form in 1936 with The General Died at Dawn. This film had a similar theme and style to director Josef von Sternberg's The Shanghai Express (1932).

The story was written by playwright Clifford Odets. It was set in the Far East and explored the "tension between democracy and authoritarianism." Actor Gary Cooper played O'Hara, an American mercenary with strong beliefs. His enemy was the complex Chinese warlord General Yang, played by Akim Tamiroff. Actress Madeleine Carroll played Judy Perrie, a young missionary caught between these forces. She eventually joins O'Hara in supporting a peasant revolt.

Milestone showed off his amazing cinematic style and technical skills in this adventure film. He used impressive tracking shots and a 5-way split-screen. He also used a famous "match dissolve" effect, transitioning from a billiard table to a door handle. This was called "one of the most expert match shots on record."

Even though Milestone later downplayed it, The General Died at Dawn is considered one of the "masterpieces" of 1930s Hollywood. He had great help from his cinematographer, art directors, and composer.

A Break from Directing (1936–1939)

After The General Died at Dawn, Milestone faced some professional problems. These included "unsuccessful projects, broken contracts and lawsuits." This put his film career on hold for three years.

He tried to direct a film version of Personal History (which Alfred Hitchcock later directed as Foreign Correspondent in 1940). He also wrote a screenplay for Dead End with Clifford Odets, but William Wyler ended up directing it.

The Night of Nights (1939): To keep working, Milestone accepted an offer to direct Pat O'Brien in this show business film. It was a "second-line" studio production.

In late 1937, Milestone signed a contract to film Road Show. However, the producer fired him for changing the comedic elements of the story. After some legal issues, Milestone was given another project: to adapt John Steinbeck's novella Of Mice and Men (1937).

Directing Of Mice and Men (1939)

Milestone really liked John Steinbeck's novella Of Mice and Men and its 1938 stage play. He was excited to direct the film, which was set during the Dust Bowl. Producer Hal Roach hoped it would be as successful as John Ford's film The Grapes of Wrath (1940), another Steinbeck adaptation. Both films reflected the social issues of the Great Depression. Milestone got Steinbeck's support for the film, and the author "essentially approved the script."

The film starts with an innovative visual opening. It sets the "mood, tone [and] themes" and introduces the main characters, George and Lennie (played by Burgess Meredith and Lon Chaney Jr.), as traveling workers. This happens even before the credits. Of Mice and Men successfully blended the book's story with film techniques. Milestone kept the "anti-omniscient" style of Steinbeck's book, matching the author's literary realism. Milestone focused on visual and sound elements to develop the characters and themes. He worked closely with the art director, cameraman, and composer Aaron Copland for the music.

The film's music earned Copland nominations for Best Musical Score and Best Original Score.

Milestone preferred to cast "relative unknowns," partly due to budget limits. He chose Lon Chaney Jr. to play the childlike Lennie Small and Burgess Meredith as his caretaker, George Milton. Actress Betty Field played Mae, the wife of the boss, Curly.

Of Mice and Men was nominated for Best Picture in 1939. However, it faced strong competition from many other classic Hollywood films that year, including The Wizard of Oz and the winner, Gone with the Wind.

Lucky Partners (1940) and My Life with Caroline (1941): Milestone's reputation remained strong after Of Mice and Men. He was hired by RKO to direct two light comedies starring Ronald Colman. He quickly completed these films, directing Ginger Rogers in Lucky Partners and Anna Lee in My Life With Caroline.

My Life With Caroline was released in August 1941, just four months before the attack on Pearl Harbor and America's entry into World War II.

World War II Films (1942–1945)

Milestone was known for directing All Quiet on the Western Front, an anti-war film. But during World War II, this made him a valuable asset for Hollywood's "patriotic and profitable" war films against fascism.

Film expert Charles Silver noted Milestone's "ability to capture battle's intrinsic spectacle." Milestone himself said, "how can you make a pacifist film without showing the violence of war?" He put aside any doubts and offered his skills to the film industry's propaganda efforts for the U.S. war.

Our Russian Front (1942)

Our Russian Front was a war documentary made from 15,000 feet of newsreel footage. This footage was taken on the Russian front by Soviet journalists during the Nazi invasion of the USSR in 1941. Milestone worked with Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens to show the struggle of Russian villagers against the German invasion. Actor Walter Huston narrated the film, and Dimitri Tiomkin composed the music.

Edge of Darkness (1943)

Milestone returned to Warner Brothers for one film after seventeen years. Edge of Darkness was the first of three successful films he made with screenwriter Robert Rossen. This film showed a change in Milestone's approach to war films.

Edge of Darkness takes place in a remote Norwegian village. The Nazi occupiers are brutal, which inspires the villagers to fight back in a single, violent uprising. Milestone uses a special technique: he first shows the terrible outcome for the villagers, then tells the story in a flashback. This film was a dramatic fantasy, and its "thematic oversimplification" reflected Hollywood's tendency for dramatic propaganda.

Milestone had mixed feelings about the cast and characters. The film starred Errol Flynn and Ann Sheridan as Norwegian freedom fighters. Helmut Dantine played the cruel Nazi commander. One biographer noted that the "frequent rasp of New York accents from Norwegians and Nazis" made the film less believable. Some actors, including Flynn, had personal problems that affected their work.

Milestone's overall direction was realistic, but it lacked his usual impressive camera work. In one powerful scene, Milestone shows the villagers' turning point. The Nazis publicly burn the local schoolteacher's library. Through expert editing and camera movement, Milestone shows how this event makes the outraged residents plan an armed uprising.

Edge of Darkness was effective war propaganda for Warner Brothers. His next project would be set on the Eastern Front for Samuel Goldwyn: The North Star (1943).

The North Star (1943)

The North Star was a war propaganda film. It showed the destruction caused by the German invasion of the USSR on a Ukrainian farming community. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked producer Sam Goldwyn to make a film celebrating America's alliance with Russia. Milestone's "lavish" production had playwright-screenwriter Lillian Hellman, cinematographer James Wong Howe, set designer William Cameron Menzies, composer Aaron Copland, and a good cast.

The script and Milestone's direction showed the peaceful settings and unity of the villagers. Milestone used a tracking shot to follow an old man through the village, introducing the main characters. An extended scene shows the villagers celebrating the harvest with food, song, and dance, like an ethnic operetta. Milestone used an overhead camera to capture the circular dances. Milestone showed his "technical mastery" through both images and sound as villagers heard the German bombers approaching, ending their peaceful life. Parts of this scene looked like real war documentaries.

After this, the film became more focused on Hollywood war propaganda, showing German cruelties. The film was praised by the mainstream press. The Academy of Arts and Sciences nominated The North Star for several awards, including Best Art Direction and Best Cinematography. However, the film did not do well at the box office.

The North Star and two other films came under scrutiny by the anti-communist House Un-American Activities Committee in the post-war years.

The North Star was later re-released in a heavily edited version. Any scenes celebrating life under the Stalinist regime were removed. It was retitled Armored Attack in 1957. The setting was changed to Hungary during its 1956 uprising, and a voice-over condemned communism.

The Purple Heart (1944)

In the Pacific War during WWII, captured American airmen were put on trial by Imperial Japan. They were accused of violating the Geneva Conventions during the 1942 Doolittle Raid over Japan, specifically for bombing civilian targets.

Based on a true event, Milestone's skill in showing the airmen's ordeal and the injustice they faced made for powerful propaganda. The Purple Heart medals, which the captured officers and men eventually received, were earned from wounds inflicted by torture to get military secrets, not from combat. Milestone defended his commitment to making propaganda films during the war.

A Walk in the Sun (1945)

In his second collaboration with screenwriter Robert Rossen, Milestone invested $30,000 of his own money into A Walk in the Sun. This showed his enthusiasm for the story.

A Walk in the Sun takes place during the U.S. invasion of Italy in WWII. A group of American soldiers must advance six miles inland to capture a German-held bridge and farmhouse. The soldiers come from different backgrounds and sometimes question the purpose of the war. One critic described the characters as "unwilling civilians, who find themselves at war in a strange land."

Milestone's view of war in A Walk in the Sun is different from his 1930 film All Quiet on the Western Front, which was a strong criticism of war. Despite some limitations, Milestone avoided the typical "heroics" of Hollywood war movies. This allowed for a sense of realism, similar to his 1930 masterpiece. Milestone's signature use of tracking shots is clear in the action scenes.

The Red Scare and Hollywood's Blacklist

When the Cold War began, Hollywood studios and the U.S. Congress looked for communist content in American films. Milestone's pro-Russian film The North Star (1943), made at the request of the U.S. government to support the alliance with the USSR, became a target.

The North Star and other films were later used against their creators during the McCarthy era. Any hint of sympathy for the Soviet Union was seen as a threat to American ideals.

Milestone supported liberal causes, which increased suspicions that he had pro-communist views during the Red Scare. He and other filmmakers were called by the HUAC for questioning.

It's not fully clear how the Hollywood blacklist affected Milestone's career. Unlike many others, he continued to find work. However, the number and quality of his film offers might have been limited. Milestone refused to talk about this part of his life, finding it very painful.

Post-War Films (1946–1951)

The films Milestone directed in the late 1940s represent "the last distinctive period" in his creative work. His first film after his series of wartime propaganda pictures was The Strange Love of Martha Ivers.

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946): A Film Noir Classic

Milestone directed The Strange Love of Martha Ivers with screenwriter Robert Rossen and excellent artistic support. This film was a "striking addition" to the post-war Hollywood genre of film noir. It mixed a dark romanticism with the visual style of German Expressionism.

The script gave the talented cast, including Barbara Stanwyck, Van Heflin, and Kirk Douglas (in his first film), a "tense, harsh" story. It criticized post-war urban America as corrupt. The cinematographer provided the film noir effects, and the music effectively blended with Milestone's visuals.

Milestone left Paramount and joined the new independent Enterprise Studios. His first film for Enterprise was Arch of Triumph, based on the 1945 novel by Erich Maria Remarque.

Arch of Triumph (1948)

Milestone's second film adaptation of an Erich Maria Remarque novel, Arch of Triumph, was highly anticipated. Enterprise Studios invested a lot of money in it.

Remarque's book had very realistic descriptions of the Paris underworld, including a revenge murder and a mercy-killing. These parts were removed from the screenplay to follow the strict Production Code Administration rules. The studio wanted a film that could compete with Gone with the Wind and hired Charles Boyer and Ingrid Bergman for the main roles. However, these famous actors were not the best fit for the characters from the book.

Milestone delivered a long, four-hour version of Arch of Triumph that Enterprise had approved. But just before its release, executives cut the film to a standard two hours. Entire scenes and characters were removed, making Milestone's work unclear. The film did keep some dark elements from the novel through effective use of expressionistic camera angles and lighting. Milestone seemed to lose interest in the project, which contributed to the film's failure.

One critic said, "Wherever the blame is placed, Arch of Triumph is a clear failure, a bad film made from a good book."

Arch of Triumph was a big failure at the box office, causing Enterprise significant losses. Milestone continued with the studio, directing a comedy for Dana Andrews and Lilli Palmer: No Minor Vices (1948).

No Minor Vices (1948): This was a "semi-sophisticated" comedy, similar to Milestone's 1941 film My Life with Caroline. It didn't add much to Milestone's body of work.

Milestone left Enterprise and joined novelist John Steinbeck at Republic Pictures to make a film version of The Red Pony (1937).

The Red Pony (1949)

Novelist John Steinbeck's The Red Pony is a series of stories about a boy and his pony, set in California's rural Salinas Valley in the early 20th century. Milestone and Steinbeck had thought about adapting these coming-of-age stories since 1940. In 1946, they partnered with Republic Pictures, a studio known for low-budget westerns but now ready to invest in a major production.

Steinbeck wrote the screenplay for The Red Pony himself. His book had four short stories, connected by characters, setting, and theme. Republic wanted a film for young audiences. To make a clear story, Steinbeck focused on two of the stories, "The Gift" and "The Leader of the People." He left out some of the harsher parts of the book. Steinbeck also willingly gave the film a more upbeat ending. One critic said this "completely distorts...the thematic thrust of Steinbeck's story sequence."

Casting for The Red Pony was difficult for Milestone in developing Steinbeck's characters. The aging ranch hand Billy Buck was played by the young and strong Robert Mitchum. His character effectively replaced the father as a male mentor to the nine-year-old Tom Tiflin (Peter Miles). The boy's mother was played by Myrna Loy, known for her sophisticated roles, here playing a rancher's wife. One critic pointed out the difficulty in portraying the boy Tom: "Perhaps no child star could capture the complexity of this role."

Even though Milestone's film didn't fully capture the book, some of the visual and sound elements were impressive. The opening scene was effective, similar to the prologue he used in his 1939 film Of Mice and Men. It introduced the natural world that would shape the characters' lives.

This was Milestone's first technicolor film. His "graceful visual touch" was enhanced by the cameraman's beautiful shots of the rural landscape. Composer Aaron Copland's highly praised film score might even be better than Milestone's visuals in telling Steinbeck's story.

The Red Pony was a successful "prestige" film for Enterprise studios. It received good reviews and did well at the box office. Milestone then moved to 20th Century Fox, where he made three films: Halls of Montezuma (1951), Kangaroo (1952), and Les Misérables (1952).

Halls of Montezuma (1951): Released in January 1951, Halls of Montezuma reflected the Cold War influence on Hollywood films during the Korean War. The story was about U.S. Marines attacking a Japanese-held island in World War II. The film focused on the suffering of one patrol trying to find a Japanese rocket bunker. Milestone's themes showed both a celebration of Marine heroism and an examination of the psychological damage to soldiers in modern warfare. Milestone said he made the movie strictly for financial reasons.

Halls of Montezuma had some similarities to Milestone's 1930 anti-war classic All Quiet on the Western Front. Like the earlier film, the cast was made up of relatively unknown actors. Their "complex and believable" characters showed the differences between experienced veterans and new recruits. The battle scenes were also similar to the 1930 movie, with Marines landing and advancing under enemy fire. The film is often seen as the beginning of a decline in his talent or his exploitation by the studios.

Later Career (1952–1962)

Milestone's final years as a filmmaker happened during the decline of the Hollywood movie studios. His last eight films reflect these changes. By 1962, shortly before his last Hollywood film Mutiny on the Bounty was released, a film magazine noted that his reputation had "somewhat tarnished."

Milestone's films in his last ten years were described as "several desperate efforts to keep working." He moved quickly between very different types of pictures.

After Halls of Montezuma (1951), 20th Century Fox sent him to Australia to use funds that had to be reinvested there. Because of this, Milestone filmed Kangaroo (1952).

Kangaroo (1952): This film was called an "antipodal Western." Milestone's main struggle was with the "ridiculous script," which was full of Western clichés moved from the American plains to the Australian outback. Milestone tried to make up for the poor story by focusing on the "landscape, flora and fauna" of the Australian outback instead of dialogue. The Technicolor cinematography achieved a documentary-like quality, using Milestone's signature panning and tracking shots.

Les Misérables (1952): For his last of three films at 20th Century Fox, Milestone directed a 104-minute version of Victor Hugo's long novel Les Misérables (1862). Fox producers gave the project their top actors, including Michael Rennie and Debra Paget, and lavish production support. The script "telescopes all the novel's famous set-pieces into this cliché-ridden" short adaptation. Milestone later said, "Oh, for Chrissake, it was just a job; I'll do it and get it over with." One critic observed that "he did little with [Hugo's] literary classic...seems to indicate the waning of Milestone's creative energies."

Working in Europe (1953–1954)

Milestone traveled to England and Italy in the 1950s looking for work. He directed a biography of a famous singer, a World War II action drama, and an international romance.

Melba (1953): Filmed in England, Melba was a movie about the famous opera singer Dame Nellie Melba. The film tried to capitalize on the popularity of recent film biographies of other famous musicians. While the star gave a decent performance, Milestone was burdened by a "worthless script" and failed to make a compelling film about Dame Melba's life. One historian reported that the film "turned out to be a disastrous flop." Milestone stayed in England in 1953 to film a war-adventure movie, They Who Dare, starring British actor Dirk Bogarde.

They Who Dare (1953): In his second-to-last war film, Milestone told the true story of British and Greek commandos. They were assigned to destroy a German airfield on the island of Rhodes during World War II. Milestone delivered an action-packed ending, but the film didn't excite critics or audiences. One biographer noted that Milestone's back-to-back box office failures "was not a good omen for an established director."

The Widow (La Vedova) (1954): Filmed in Italy, this was a "soap opera-ish love triangle" starring Patricia Roc.

Pork Chop Hill (1959)

Pork Chop Hill is considered the third film in an "informal war trilogy" with Milestone's All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and A Walk in the Sun (1945).

The film was based on a true account of a Korean War battle. Milestone had a realistic story to work with for his final film about men at war.

The plot involves a U.S. infantry company's attack to capture and defend a small "hill" against a much larger Chinese battalion. This battle was important during high-level truce negotiations, as it showed each side's determination. To take and hold the position, American troops suffered heavy losses. The military eventually sent reinforcements, but with little appreciation for the soldiers' sacrifices. One critic summarized it as "The story of a battle for a strategic point of little military value, but of great moral value."

Milestone and the film's star, Gregory Peck, disagreed on the film's message. Peck wanted a more political message, comparing the battle to famous American battles like Bunker Hill. The studio's final editing of the film changed Milestone's original message about the pointlessness of war.

Milestone distanced himself from the final cut, saying "Pork Chop Hill became a film I am not proud of...[merely] one more war movie."

Besides the rising star Peck, Milestone mainly cast unknown actors for the soldiers, including Woody Strode, Harry Guardino, and Robert Blake.

Ocean's 11 (1960)

Milestone accepted an offer from Warner Brothers to direct Ocean's 11, a comedy-heist movie. The story was about a group of former military friends who plan a complex robbery of Las Vegas's biggest casinos. The movie starred the famous Rat Pack, led by Frank Sinatra. Milestone's past success with both comedies and war films might have influenced Warner's decision to hire him.

The film had a "preposterous" screenplay. Milestone delivered a film that seemed unsure whether it was making fun of American greed or celebrating it. Many people think the film was not worthy of Milestone's talents, even though it was a box office success.

Mutiny on the Bounty (1962)

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's remake of the 1935 film Mutiny on the Bounty was a huge, expensive production. The studio risked over $20 million on the "ill-starred" 1962 Mutiny on the Bounty, but only got back less than half of its investment.

The 65-year-old Milestone took over directing in February 1961. The previous director had left because of a bad script, terrible weather in Tahiti, and disagreements with the lead actor, Marlon Brando. Milestone was tasked with bringing order to the production and controlling the "unpredictable" Brando. Milestone found that only a few scenes had been shot.

The making of the 1962 Mutiny on the Bounty was full of arguments between Milestone and Brando. Brando tried to take creative control over his character, Fletcher Christian. He worked with screenwriters and independently of Milestone. This led Milestone to step back from some scenes, giving control to Brando. One film critic called it "the Brando-Milestone" Mutiny on the Bounty, noting that "the central figure in every sense is Marlon Brando, not Lewis Milestone."

Mutiny on the Bounty is not considered typical of Milestone's work. It was the last completed film for which Milestone received credit.

Television Work and Unfinished Projects (1955–1965)

After finishing The Widow (La Vedova) (1955), Milestone returned to the United States. With the Hollywood studio system changing, Milestone started working in television to stay busy. Five years passed before he completed another feature film. In 1956–1957, Milestone worked with actor-producer Kirk Douglas on a movie about a powerful businessman, but the project was stopped.

Milestone directed episodes for television dramas in 1957, including Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Schlitz Playhouse. In 1958, Milestone directed actor Richard Boone in the television western Have Gun – Will Travel. Milestone began filming PT 109 (1963), a movie about John F. Kennedy's experiences as a torpedo boat commander in the Pacific War. After several weeks, Jack L. Warner removed Milestone from the project and replaced him.

Milestone didn't enjoy television productions, but he returned to them after Mutiny on the Bounty (1962). He directed episodes for Arrest and Trial and The Richard Boone Show in 1963. Milestone's final film effort was for a multinational project in 1965, The Dirty Game. He shot one episode before being replaced due to his declining health.

Several of Milestone's films—Seven Sinners, The Front Page, The Racket, and Two Arabian Knights—were preserved by the Academy Film Archive in 2016 and 2017.

Milestone's Final Years

Milestone's health declined in the 1960s. He suffered a stroke in 1978, shortly after his wife of 43 years, Kendall Lee, passed away.

After more illnesses, Milestone died on September 25, 1980, at the UCLA Medical Center. He was just five days shy of his 85th birthday.

Lewis Milestone's last wish was for Universal Studios to restore All Quiet on the Western Front to its original length. This wish was granted almost two decades later. This restored version is what people widely see today. Milestone is buried in the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles.

Lewis Milestone's Film Legacy

Lewis Milestone's career spanned thirty-seven years (1925–1962), and he directed 38 feature films. He was a major contributor to film art and entertainment during the Hollywood Golden Age. Like many directors of his time, Milestone worked in both the silent and sound film eras. His style was complex and efficient, mixing the visual elements of Expressionism with the Realism that came with natural sound.

When talking pictures began, the 29-year-old Milestone used his talents to adapt Erich Maria Remarque's powerful anti-war novel All Quiet on the Western Front. This film is considered his greatest work. It is widely seen as the peak of his career; Milestone's later films never reached the same artistic or critical success. One biographer noted: "The problem of making a classic film early in a career is that it sets a standard of comparison for all future work that is in some instances unfair." Milestone's films sometimes showed his technical skill, but they often lacked the strong connection to a story that made his early classic so powerful.

Milestone's later work in Hollywood included both excellent and average films. They were varied but often lacked a clear artistic purpose. His technical talents were perhaps the most consistent feature. Film critic Andrew Sarris said that "Milestone's fluid camera style has always been dissociated from any personal viewpoint. He is almost the classic example of the uncommitted director."

Film critic Richard Koszarski considered Milestone "one of the Thirties more independent spirits." However, like many early directors, his relationship with the powerful studio system was not always productive.

Lewis Milestone's Academy Awards

| Year | Award | Film | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1927–28 | Academy Award for Best Director (Comedy) | Two Arabian Knights | Won |

| 1929–30 | Academy Award for Best Director | All Quiet on the Western Front | Won |

| 1930–31 | Academy Award for Best Director | The Front Page | Nominated |

| 1939 | Academy Award for Best Picture | Of Mice and Men | Nominated |

Lewis Milestone's Filmography

- 1918 – The Toothbrush (director)

- 1918 – Posture (director)

- 1918 – Positive (director)

- 1919 – Fit to Win (director)

- 1922 – Up and at 'Em (screenwriter)

- 1923 – Where the North Begins (editor)

- 1924 – The Yankee Consul (screenwriter)

- 1924 – Listen Lester (screenwriter)

- 1925 – The Mad Whirl (screenwriter)

- 1925 – Dangerous Innocence (screenwriter)

- 1925 – The Teaser (screenwriter)

- 1925 – Bobbed Hair (screenwriter)

- 1925 – Seven Sinners (director and screenwriter)

- 1926 – The Caveman (director)

- 1926 – The New Klondike (director)

- 1926 – Fine Manners (director, uncredited)

- 1927 – The Kid Brother (director, uncredited)

- 1927 – Two Arabian Knights (director)

- 1928 – The Garden of Eden (director)

- 1928 – Tempest (director and screenwriter, uncredited)

- 1928 – The Racket (director)

- 1929 – New York Nights (director)

- 1929 – Betrayal (director)

- 1930 – All Quiet on the Western Front (director)

- 1931 – The Front Page (director)

- 1932 – Rain (director)

- 1933 – Hallelujah, I'm a Bum (director)

- 1934 – The Captain Hates the Sea (director)

- 1935 – Paris in Spring (director)

- 1936 – Anything Goes (director)

- 1936 – The General Died at Dawn (director)

- 1939 – Of Mice and Men (director)

- 1939 – The Night of Nights (director)

- 1940 – Lucky Partners (director and screenwriter)

- 1941 – My Life with Caroline (director)

- 1943 – Edge of Darkness (director)

- 1943 – The North Star (director)

- 1944 – Guest in the House (director, uncredited)

- 1944 – The Purple Heart (director)

- 1945 – A Walk in the Sun (director)

- 1946 – The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (director)

- 1948 – Arch of Triumph (director and screenwriter)

- 1948 – No Minor Vices (director)

- 1949 – The Red Pony (director)

- 1951 – Halls of Montezuma (director)

- 1952 – Les Misérables (director)

- 1952 – Kangaroo (director)

- 1953 – Melba (director)

- 1954 – They Who Dare (director)

- 1955 – La Vedova X (director and screenwriter)

- 1957 – Alfred Hitchcock Presents (TV series) (director)

- 1957 – Schlitz Playhouse (TV series) (director)

- 1957 – Suspicion (TV series) (director)

- 1958 – Have Gun – Will Travel (TV series) (director)

- 1959 – Pork Chop Hill (director)

- 1960 – Ocean's 11 (director)

- 1962 – Mutiny on the Bounty (director)

- 1963 – The Richard Boone Show (TV series) (director)

- 1963 – Arrest and Trial (TV series) (director)

|

See also

In Spanish: Lewis Milestone para niños

In Spanish: Lewis Milestone para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |