Sven Hedin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sven Hedin

|

|

|---|---|

Sven Hedin around 1910

|

|

| Born | Sven Anders Hedin 19 February 1865 Stockholm, Sweden |

| Died | 26 November 1952 (aged 87) Stockholm, Sweden |

| Language | Swedish |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Notable awards | Vega Medal (1898) Livingstone Medal (1902) Victoria Medal (1903) |

Sven Anders Hedin (born February 19, 1865 – died November 26, 1952) was a famous Swedish geographer, mapmaker, explorer, photographer, and writer. He also drew pictures for his own books.

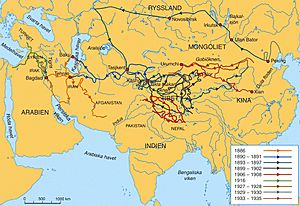

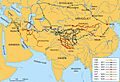

During four big trips to Central Asia, he helped people in the West learn about the Transhimalaya mountains. He also found where the Brahmaputra, Indus, and Sutlej rivers begin. He mapped Lop Nur lake and found old cities, burial sites, and parts of the Great Wall of China in the deserts of the Tarim Basin.

In his book Från pol till pol (From Pole to Pole), Hedin wrote about his journeys across Asia and Europe in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He visited many places like Turkey, the Caucasus region, Tehran, Iraq, lands of the Kyrgyz people, the Russian Far East, India, China, and Japan. After he passed away, his Central Asia Atlas was published, which was the final part of his life's work.

Contents

Becoming an Explorer

When Sven Hedin was 15, he saw the famous Arctic explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld return home after sailing the Northern Sea Route for the first time. This amazing event made young Sven want to become an explorer too.

He studied with a German geographer named Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen, who was an expert on China. This made Hedin love Germany and made him even more determined to explore Central Asia. He wanted to map the last unknown parts of Asia.

After getting his doctorate degree and learning several languages, he made two trips through Persia. He then decided to become an explorer, even though his teacher suggested he study more about how to do geographic research. Hedin was eager to explore the wild parts of Asia and fill in the blank spaces on maps.

Exploring Unknown Lands

Between 1894 and 1908, Sven Hedin went on three brave expeditions. He traveled through the mountains and deserts of Central Asia. He mapped and studied parts of Chinese Turkestan (now Xinjiang) and Tibet that no Europeans had explored before. When he returned to Stockholm in 1909, he was welcomed like a hero, just like Nordenskiöld had been.

In 1902, he became the last Swede to be given a noble title. He was seen as one of Sweden's most important people. He was a member of two science academies, which meant he helped choose Nobel Prize winners for both science and literature. Hedin never married or had children.

Mapping Central Asia

Hedin's notes from his expeditions helped create very accurate maps of Central Asia. He was one of the first European explorers to hire local scientists and assistants for his trips. Even though he was mainly an explorer, he was also the first to uncover the ruins of ancient Buddhist cities in Chinese Central Asia. He was very determined, surviving many dangerous situations from both people and nature during his long career.

His detailed scientific notes and popular travel books were filled with his own photos, watercolor paintings, and drawings. He also wrote adventure stories for young readers and gave lectures around the world, which made him famous.

Meeting Important People

Because he was an expert on Turkestan and Tibet, Hedin could meet with kings, queens, and politicians in Europe and Asia. He also met with leaders of geographic societies and scholarly groups. They all wanted his special knowledge about Central Asia. They gave him gold medals, fancy awards, honorary degrees, and helped him with money and supplies for his expeditions.

Hedin was an important person in the "Great Game," which was a struggle between Britain and Russia for power in Central Asia. Explorers like Hedin helped fill in the "white spaces" on maps, giving valuable information to these powerful countries.

Hedin was honored by many important people, including:

- King Oscar II of Sweden (1890)

- Shah Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar (1890)

- Czar Nicholas II of Russia (1896, 1909)

- Kaiser Franz Joseph I of Austria (from 1898)

- Viceroy of India Lord Curzon (1902)

- Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany (1903, 1914, 1917, 1926, 1936)

- The 9th Panchen Lama Thubten Choekyi Nyima (1907, 1926, 1933)

- Emperor Mutsuhito of Japan (1908)

- Pope Pius X (1910)

- U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (1910)

- Chiang Kai-shek (1929, 1935)

- Adolf Hitler (1935, 1939, 1940)

Later Life and Discoveries

Hedin was very concerned about the safety of Scandinavia. He supported building a battleship called Sverige. During World War I, he publicly supported Germany. Because of this, his scientific reputation was harmed among Germany's enemies, and he lost support for his future expeditions.

After a difficult lecture tour in 1923, he went to Beijing. He wanted to explore Chinese Turkestan (Xinjiang), but the area was too unstable. Instead, he traveled through Mongolia by car and across Siberia by train.

Between 1927 and 1935, with money from Sweden and Germany, Hedin led an international and scientific expedition called the Sino-Swedish Expedition. Thirty-seven scientists from six countries took part. They studied Mongolia and Chinese Turkestan. Even with protests from China, Hedin managed to make it a Chinese expedition too, getting Chinese scientists to join.

Despite his health problems, a civil war in Chinese Turkestan, and being held captive for a long time, Hedin faced many challenges. He was 70 years old and had to raise money during the Great Depression. He also had to organize supplies in a war zone and get permission to enter areas controlled by local leaders. However, the expedition was a great scientific success. The old artifacts found were studied in Sweden for three years, then returned to China as agreed.

From 1937, the scientific information from the expedition was published in over 50 books by Hedin and other scientists. This made it available for researchers worldwide. When he ran out of money for printing, he even pawned his large and valuable library to publish more books.

In 1935, Hedin shared his special knowledge about Central Asia with the Swedish, Chinese, and German governments through lectures and meetings.

World War II and Its Aftermath

Hedin was not a Nazi, but he hoped that Nazi Germany would protect Scandinavia from the Soviet Union. This brought him close to Nazi leaders, who used his fame as a writer. This damaged his reputation and made him feel isolated from society and science. However, in his letters and talks with leading Nazis, he successfully helped save ten people who were sentenced to death. He also helped Jews who had been sent to Nazi concentration camps to be released or survive.

After World War II, U.S. troops took documents related to Hedin's planned Central Asia Atlas. Later, the U.S. Army Map Service asked for Hedin's help and paid for his life's work, the Central Asia Atlas, to be printed and published. This atlas showed how much Hedin had achieved between 1893 and 1935.

Even though Hedin's research was not talked about much in Germany and Sweden for decades because of his connection to Nazi Germany, his scientific work was translated into Chinese. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences used it in their research. Following Hedin's suggestions to the Chinese government in 1935, the routes he mapped were used to build roads and train tracks. Dams and canals were also built to water new farms in Xinjiang. The iron, manganese, oil, coal, and gold found during the Sino-Swedish Expedition were also mined.

The expedition also discovered many Asian plants and animals that were new to science, as well as fossils of dinosaurs and other extinct animals. Many of these were named after Hedin, using the scientific name hedini. One important discovery remained unknown to Chinese researchers until the year 2000: in the Lop Nur desert, Hedin found ruins of signal towers in 1933 and 1934. These showed that the Great Wall of China once reached as far west as Xinjiang.

From 1931 until his death in 1952, Hedin lived in a modern high-rise building in Stockholm. He lived with his siblings on the top three floors. From his balcony, he had a wide view over Riddarfjärden Bay and Lake Mälaren.

On October 29, 1952, Hedin's will gave the rights to his books and personal belongings to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The Sven Hedin Foundation was created soon after to hold all these rights.

Hedin died in Stockholm in 1952. Representatives from the Swedish royal family, the government, the Swedish Academy, and diplomats attended his memorial service. He is buried in the cemetery of Adolf Fredrik church in Stockholm.

Biography

Childhood Dreams

Sven Hedin was born in Stockholm. His father, Ludwig Hedin, was the Chief Architect of Stockholm. When Sven was 15 years old, he saw the Swedish Arctic explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld return home after sailing the Northern Sea Route.

Hedin wrote about this moment in his book My Life as an Explorer:

On April 24, 1880, the ship Vega sailed into Stockholms ström. The whole city was lit up. Buildings around the harbor glowed with many lamps and torches. Gas flames showed the constellation of Vega on the castle. In this sea of light, the famous ship entered the harbor. I was standing on the Södermalm heights with my parents and siblings, where we had a great view. I felt very excited. I will remember this day forever, as it decided my future. Loud cheers came from the docks, streets, windows, and rooftops. "That's how I want to return home someday," I thought.

First Trip to Iran

In May 1885, Hedin finished high school. He then became a private tutor for a student named Erhard Sandgren, traveling with him to Baku. Sandgren's father worked there in the oil fields. After this, Hedin took a short course in mapmaking for army officers and some drawing lessons. This was all his formal training in these areas.

On August 15, 1885, he went to Baku with Erhard Sandgren. He taught him for seven months and also started learning many languages himself, including Latin, French, German, Persian, Russian, English, and Tatar. Later, he learned more Persian dialects, Turkish, Kyrgyz, Mongolian, Tibetan, and some Chinese.

On April 6, 1886, Hedin left Baku for Iran (then called Persia). He traveled by boat over the Caspian Sea, rode through the Alborz Mountains to Tehran, Esfahan, Shiraz, and the port city of Bushehr. From there, he took a ship up the Tigris River to Baghdad (then part of the Ottoman Empire). He returned to Tehran, then traveled through the Caucasus and across the Black Sea to Constantinople. Hedin arrived back in Sweden on September 18, 1886.

In 1887, Hedin published a book about these travels called Through Persia, Mesopotamia and the Caucasus.

His Studies and Second Trip

From 1886 to 1888, Hedin studied geology, mineralogy, zoology, and Latin in Stockholm and Uppsala. In December 1888, he earned a degree in Philosophy. From October 1889 to March 1890, he studied in Berlin.

On May 12, 1890, he went back to Iran as an interpreter and vice-consul for a Swedish group. They were there to give the Shah of Iran a special award. Hedin spoke with the Shah and later went with him to the Elburz Mountains. On July 11, 1890, he and three others climbed Mount Damavand, where he gathered information for his university paper. In September, he traveled on the Silk Road through cities like Mashhad, Ashgabat, Bukhara, Samarkand, Tashkent, and Kashgar to the edge of the Taklamakan Desert. On his way home, he visited the grave of the Russian explorer Nikolay Przhevalsky in Karakol. He was back in Stockholm on March 29, 1891. He wrote two books about this journey.

Becoming a Full-Time Explorer

On April 27, 1892, Hedin went to Berlin to continue his studies. In July, he went to the University of Halle-Wittenberg in Halle. In the same month, he received his Doctor of Philosophy degree for a paper about his observations on Mount Damavand.

Hedin decided to become a full-time explorer. He loved the idea of traveling to the last mysterious parts of Asia and mapping areas that were completely unknown in Europe. As an explorer, Hedin became important to Asian and European powers. They invited him to give many lectures, hoping to get information about inner Asia, which they saw as important to their influence.

First Major Expedition (1893-1897)

Between 1893 and 1897, Hedin explored the Pamir Mountains, traveled through the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang, crossed the Taklamakan Desert, and studied northern Tibet. He covered about 26,000 kilometers on this trip and mapped 10,498 kilometers on 552 maps. About 3,600 kilometers of his journey were through areas that had never been mapped before.

He started this expedition on October 16, 1893, from Stockholm, traveling through Saint Petersburg and Tashkent to the Pamir Mountains. He tried several times to climb the 7,546-meter-high Muztagh Ata mountain but was not successful. He stayed in Kashgar until April 1895.

On April 10, he left with three local guides to cross the Taklamakan Desert. They ran out of water, and seven camels died of thirst. Two of his guides also died. Some sources say Hedin did not fill his water containers completely at the start. When he realized his mistake, it was too late to go back. Driven by his goal, Hedin went ahead alone on horseback with one servant. When that servant also collapsed from thirst, Hedin left him behind but managed to reach a water source. He then returned with water and saved his servant.

In January 1896, Hedin visited the 1,500-year-old abandoned cities of Dandan Oilik and Kara Dung in the Taklamakan Desert. In early March, he discovered Lake Bosten, one of Central Asia's largest inland lakes. He mapped Lake Kara-Koshun and returned to Khotan on May 27. On June 29, he started from there with his group across northern Tibet and China to Beijing, arriving on March 2, 1897. He returned to Stockholm through Mongolia and Russia.

Second Major Expedition (1899-1902)

Another expedition to Central Asia took place from 1899 to 1902. Hedin traveled through the Tarim Basin, Tibet, and Kashmir to Calcutta. He explored the Yarkand, Tarim, and Kaidu rivers. He found the dry riverbed of the Kum-darja and the dried-out lake bed of Lop Nur.

Near Lop Nur, he discovered the ruins of an ancient walled city called Loulan. This city, about 340 by 310 meters, was once a royal city and later a Chinese army town. He found a brick building for the military commander, a stupa (a Buddhist monument), and 19 houses made of poplar wood. He also found a wooden wheel from a horse-drawn cart and hundreds of documents written on wood, paper, and silk. These documents told the history of Loulan, which was abandoned around 330 CE because the lake it depended on for water dried up.

During his travels in 1900 and 1901, he tried to reach the city of Lhasa, which was forbidden to Europeans, but he failed. He continued to Leh in India. From Leh, Hedin traveled to Lahore, Delhi, Agra, Lucknow, Benares, and then to Calcutta. There, he met George Nathaniel Curzon, who was England's Viceroy to India.

This expedition resulted in 1,149 pages of maps, showing newly discovered lands. Hedin was the first to describe special wind-eroded landforms called yardangs in the Lop Desert.

Third Major Expedition (1905-1908)

Between 1905 and 1908, Hedin explored the deserts of central Iran, the western highlands of Tibet, and the Transhimalaya mountains, which were sometimes called the Hedin Range. He visited the 9th Panchen Lama in the city of Tashilhunpo in Shigatse. Hedin was the first European to reach the Kailash region, including the sacred Lake Manasarovar and Mount Kailash, which Buddhists and Hindus believe is the center of the earth.

The most important goal of this expedition was to find the sources of the Indus and Brahmaputra Rivers, both of which Hedin found. From India, he returned to Stockholm through Japan and Russia.

He brought back many rock samples from this expedition, which are now studied in Munich, Germany. These rocks, like limestone and granite, show how diverse the geology of the regions Hedin visited was.

Travels in Mongolia (1923)

In 1923, Hedin traveled to Beijing through the USA, where he visited the Grand Canyon, and Japan. Because of political problems in China, he had to cancel an expedition to Xinjiang. Instead, in November and December, he traveled by car with Frans August Larson from Peking through Mongolia to Ulaanbaatar and then to Ulan-Ude, Russia. From there, he took the Trans-Siberian Railway to Moscow.

Fourth Major Expedition (1927-1935)

Between 1927 and 1935, Hedin led an international Sino-Swedish Expedition. This expedition studied the weather, maps, and ancient history of Mongolia, the Gobi Desert, and Xinjiang.

Hedin described it as a "traveling university." The scientists worked mostly on their own, while he managed things, talked with local leaders, made decisions, organized supplies, raised money, and recorded the routes. He gave archaeologists, astronomers, botanists, geographers, geologists, meteorologists, and zoologists from Sweden, Germany, and China a chance to join and do research in their fields.

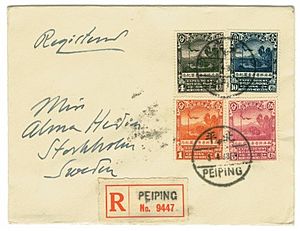

Hedin met Chiang Kai-shek in Nanjing, who then became a supporter of the expedition. The Sino-Swedish Expedition was even honored with a Chinese postage stamp series. The stamps showed camels at a camp with the expedition flag and Chinese text. Hedin used these stamps to help pay for the expedition.

The first part of the expedition (1927-1932) went from Beijing to Mongolia, across the Gobi Desert, through Xinjiang, and into the northern and eastern parts of the Tarim Basin. The expedition had many scientific successes. For example, they found important deposits of iron, manganese, oil, coal, and gold, which were very important for China's economy.

From late 1933 to 1934, Hedin led a Chinese expedition for the government under Chiang Kai-shek. This trip was to study how to water land and to draw plans for building two roads suitable for cars along the Silk Road from Beijing to Xinjiang. Following his plans, large irrigation systems were built, new towns were set up, and roads were constructed.

One part of Central Asian geography that Hedin studied for decades was the "wandering lake" Lop Nur. In May 1934, he started a river expedition to this lake. For two months, he traveled the Kaidu River and the Kum-Darja to Lop Nur, which had been filled with water since 1921.

His group of trucks was taken over by a Chinese Muslim general named Ma Zhongying. Hedin was held by Ma Zhongying and met other generals. Ma Zhongying's assistant told Hedin that the general controlled the whole region and Hedin could pass safely. However, some of Ma Zhongying's troops attacked Hedin's vehicles.

For the return trip, Hedin chose the southern Silk Road route to Xi'an, arriving on February 7, 1935. He continued to Beijing to meet President Lin Sen and to Nanjing to meet Chiang Kai-shek. He celebrated his 70th birthday on February 19, 1935, with 250 members of the government. On this day, he received a high honor, the Order of Brilliant Jade.

At the end of the expedition, Hedin was in a difficult financial situation. He had large debts, which he paid back with money from his books and lectures. In the months after his return, he gave 111 lectures in Germany and 19 in other countries. He traveled a huge distance for these talks. He met Adolf Hitler in Berlin before a lecture on April 14, 1935.

Political Views

Hedin was a monarchist, meaning he supported kings and queens. From 1905, he spoke out against Sweden becoming more democratic. He warned about dangers from Russia and wanted Sweden to form an alliance with Germany. He believed Sweden needed a stronger national defense and military.

He greatly admired Kaiser Wilhelm II and even visited him after he was no longer emperor. Hedin felt that Soviet Russia was a big threat to the West. This might be why he supported Germany during both World Wars.

He saw World War I as a fight for the German people, especially against Russia. He wrote books supporting Germany. Because of this, he lost friends in France and England and was removed from the British Royal Geographical Society. Germany's defeat in World War I deeply affected him.

Hedin and Nazi Germany

Hedin's traditional and pro-German views led him to sympathize with the Third Reich. This caused much controversy later in his life. Adolf Hitler admired Hedin early on, and Hedin was impressed by Hitler's strong sense of nationalism. He saw Hitler's rise to power as a way for Germany to become strong again and challenge Soviet Communism.

However, Hedin was not a blind supporter of the Nazis. His own beliefs were based on traditional, Christian, and conservative values. He disagreed with some parts of Nazi rule and sometimes tried to convince the German government to stop its anti-religious and anti-Jewish actions.

Hedin met Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders many times and wrote letters to them regularly. These letters were usually about scheduling, birthday wishes, Hedin's books, and requests for pardons for people sentenced to death. He also asked for mercy, release, or permission to leave the country for people held in prisons or concentration camps.

On October 29, 1942, Hitler read Hedin's book, America in the Battle of the Continents. In the book, Hedin argued that President Roosevelt was responsible for the war starting in 1939 and that Hitler had tried hard to prevent it. Hitler was greatly influenced by this book.

The Nazis tried to get close to Hedin by giving him awards. They asked him to give a speech at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. They made him an honorary member of the German-Swedish Union in Berlin. In 1938, they gave him the City of Berlin's Badge of Honor. For his 75th birthday in 1940, they gave him the Order of the German Eagle, an award also given to Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh.

On January 15, 1943, he received a gold medal from the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. The next day, he received an honorary doctorate from Munich University. On the same day, the Nazis created the Sven Hedin Institute for Inner Asian Research. This institute was supposed to promote Hedin's scientific work but was misused by Heinrich Himmler.

Hedin supported the Nazis in his writings. After Nazi Germany fell, he did not regret working with the Nazis because he felt this cooperation allowed him to save many victims from execution or death in concentration camps.

Criticism of the Nazis

In 1937, Hedin refused to publish his book Deutschland und der Weltfrieden (Germany and World Peace) in Germany. This was because the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda wanted him to remove parts that criticized the Nazis. In a letter, Hedin explained his criticism:

When we first talked about my book, I said I only wanted to write fairly, scientifically, and honestly. You agreed that was fine. Now, I wrote in a friendly way that removing respected Jewish professors who have done great things for humanity hurts Germany. This has caused many people abroad to speak against Germany. I took this position only for Germany's good.

My worry that German youth's education, which I otherwise praise, is lacking in religious matters comes from my love for the German nation. As a Christian, I feel it's my duty to say this openly, believing that Luther's religious nation will understand me.

I have never gone against my conscience and will not do so now. Therefore, no parts will be removed.

Hedin later published this book in Sweden.

Helping Jewish People

After Hedin refused to remove his criticism of the Nazis from his book, the Nazis took away the passports of Hedin's Jewish friend Alfred Philippson and his family in 1938. They did this to keep them in Germany as a way to pressure Hedin. Because of this, Hedin wrote more favorably about Nazi Germany in his next book, Fünfzig Jahre Deutschland, and allowed the Ministry of Propaganda to censor it. He published this book in Germany.

On June 8, 1942, the Nazis increased the pressure by sending Alfred Philippson and his family to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. By doing this, they forced Hedin to write his book Amerika im Kampf der Kontinente with the help of the Ministry of Propaganda. In return, the Nazis gave Alfred Philippson's family special privileges that helped them survive.

Hedin regularly sent food packages to Alfred Philippson in Theresienstadt. On May 29, 1946, Alfred Philippson wrote to Hedin, thanking him for saving his family:

My dear Hedin! Now that letters can be sent abroad, I can write to you… We often think with deep thanks of our rescuer, who alone made it possible for us to survive the terrible three years in Theresienstadt concentration camp, which is a true miracle at my age. You will have heard that we few survivors were finally freed just days before we were to be gassed. We, my wife, daughter, and I, were then brought home to Bonn…

Hedin replied on July 19, 1946:

…It was wonderful to find out that our efforts were not in vain. In these difficult years, we tried to save over a hundred other unfortunate people who had been sent to Poland, but mostly without success. We were able to help a few Norwegians. My home in Stockholm became like an information and help office, and I was greatly supported by Dr. Paul Grassmann from the German embassy in Stockholm. He also did everything possible to help this humanitarian work. But almost no case was as lucky as yours, dear friend! And how wonderful that you are back in Bonn…

The names of the other people Hedin tried to save are not yet known.

Helping Norwegians

Hedin also helped the Norwegian author Arnulf Øverland and the Oslo professor Didrik Arup Seip, who were held in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. He managed to get Didrik Arup Seip released, but his efforts to free Arnulf Øverland were not successful. However, Arnulf Øverland did survive the concentration camp.

Hedin also helped save ten Norwegians who were sentenced to death for alleged spying in 1941. Hedin successfully asked Adolf Hitler to change their sentences. Their death penalties were changed to ten years of forced labor. Other Norwegians who had been sentenced to forced labor also received shorter sentences because of Hedin's requests.

Hedin also helped Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, a German general, who was sentenced to death by a British court after the war. Hedin argued that von Falkenhorst had also tried to help the ten Norwegians. Von Falkenhorst's death sentence was changed to 20 years in prison, and he was released early in 1953.

Awards and Legacy

Because of his great achievements, King Oskar II made Hedin a nobleman in 1902. He was the last Swede to receive such a title. Hedin's coat of arms is displayed in the Riddarhuset, the assembly house of Swedish nobility in Stockholm.

In 1905, Hedin became a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and in 1909, of the Royal Swedish Academy of War Sciences. From 1913 to 1952, he was an elected member of the Swedish Academy. In this role, he helped choose Nobel Prize winners.

He was an honorary member of many Swedish and foreign scientific groups and institutions. They honored him with about 40 gold medals. Twenty-seven of these medals can be seen in Stockholm at the Royal Coin Cabinet.

He received honorary doctorates from many universities, including Oxford (1909), Cambridge (1909), Heidelberg (1928), Uppsala (1935), and Munich (1943).

Many countries gave him medals. In Sweden, he received the Order of the Polar Star and the Order of Vasa. In the United Kingdom, King Edward VII made him a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire. As a foreigner, he could not use the title "Sir," but he could put "KCIE" after his name. Hedin also received the Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle.

Many things have been named in his honor: a glacier (the Sven Hedin Glacier), a lunar crater (Hedin), a type of flowering plant (Gentiana hedini), beetles (Longitarsus hedini and Coleoptera hedini), a butterfly (Fumea hedini Caradja), a spider (Dictyna hedini), a fossil mammal (Tsaidamotherium hedini), and a fossil reptile (Lystrosaurus hedini). Streets and squares in various cities are also named after him.

A permanent exhibition of items found by Hedin on his expeditions is located in the Stockholm Ethnographic Museum.

In the Adolf Fredrik church, there is a memorial plaque for Sven Hedin by Liss Eriksson, installed in 1959. It shows a globe with Asia in front, topped with a camel. It has a Swedish message: "Asia's unknown expanses were his world—Sweden remained his home."

The Sven Hedin Firn in North Greenland was also named after him.

Images for kids

-

Stockholm on April 24, 1880.

See also

In Spanish: Sven Hedin para niños

In Spanish: Sven Hedin para niños