Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

G. W. F. Hegel

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Jakob Schlesinger, 1831

|

|

| Born |

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

27 August 1770 Stuttgart, Duchy of Württemberg

|

| Died | 14 November 1831 (aged 61) |

| Education |

|

|

Notable work

|

|

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions |

|

|

Main interests

|

|

| Signature | |

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (born August 27, 1770 – died November 14, 1831) was an important German philosopher. He is known as one of the main thinkers in German idealism and a key person in modern Western philosophy. His ideas have had a huge impact on many areas of philosophy. These include how we understand reality (metaphysics), how we know things (epistemology), and ideas about government, history, art, and religion.

Hegel was born in Stuttgart during a time of big changes in Europe. He lived through the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, which greatly influenced his thinking. His most famous books are The Phenomenology of Spirit and The Science of Logic. He also gave many lectures at the University of Berlin.

Hegel tried to fix problems in modern philosophy, especially the idea of a separate mind and body. He often looked back to ancient philosophy, like the ideas of Aristotle. Hegel believed that reason and freedom are things we achieve over time, not something we are just born with. He thought that ideas should be judged by their own rules, and that we can only trust truths that have been tested by experience.

Hegel believed that being able to make our own choices (self-determination) is what makes us human. He said that logic, nature, and spirit are all connected. His ideas continue to influence many different types of philosophy today.

Hegel's Life Story

Early Years and Education

Growing Up in Stuttgart (1770–1800)

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was born on August 27, 1770, in Stuttgart, Germany. His family called him Wilhelm. His father, Georg Ludwig, worked for the local government. His mother, Maria Magdalena Louisa, was the daughter of a lawyer. She passed away when Hegel was thirteen from a serious illness. Hegel and his father also got sick but survived.

Hegel had a sister, Christiane Luise, and a brother, Georg Ludwig. His brother later died as an officer during Napoleon's war in Russia in 1812. Hegel started school at age three. By age five, he was learning Latin, taught by his mother. In 1776, he went to a high school called Eberhard-Ludwigs-Gymnasium. He loved to read and copied many parts of books into his diary. He read poets and thinkers from the Age of Enlightenment, like Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. His education focused on Enlightenment ideas and classical ancient studies.

College Days in Tübingen

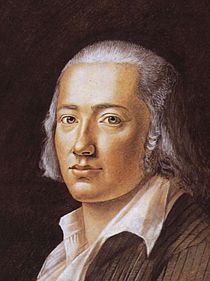

At eighteen, Hegel went to the Tübinger Stift, a Protestant seminary (a school for religious studies) connected to the University of Tübingen. He shared a room with two future famous thinkers: the poet Friedrich Hölderlin and the philosopher Friedrich Schelling. They became close friends and influenced each other's ideas. They didn't like the strict rules of the seminary. Hegel likely went there because it was funded by the state, even though he didn't want to become a minister.

All three friends admired ancient Greek culture. Hegel also read Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Lessing. They were excited about the French Revolution. Even though the violence of the 1793 Reign of Terror worried Hegel, he still supported the ideas of the revolution. He even toasted the storming of the Bastille every July 14th. While Schelling and Hölderlin discussed Kant's philosophy, Hegel was more interested in making philosophical ideas easy for everyone to understand. He didn't start deeply studying Kant's ideas until 1800.

Working as a Tutor (1793–1800)

After finishing seminary, Hegel worked as a private tutor (called Hofmeister) for a rich family in Berne from 1793 to 1796. During this time, he wrote texts like Life of Jesus. His relationship with his employers became difficult. So, with help from Hölderlin, he found a similar job with a wine merchant's family in Frankfurt in 1797.

In Frankfurt, Hölderlin had a big impact on Hegel. In Berne, Hegel had criticized traditional Christianity. But in Frankfurt, he explored the idea of love as the true meaning of religion. An important, unsigned paper called "The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism" was written around this time. It might have been written by Hegel, Schelling, or Hölderlin. Hegel also wrote essays like "Fragments on Religion and Love" and "The Spirit of Christianity and Its Fate."

Career and Major Works

Jena, Bamberg, and Nürnberg (1801–1816)

In 1801, Hegel moved to Jena because his friend Schelling was a professor there. Hegel became an unsalaried lecturer at the University of Jena. He wrote a paper called De Orbitis Planetarum. He also completed his essay The Difference Between Fichte's and Schelling's System of Philosophy. He taught classes on logic and metaphysics.

In 1802, Schelling and Hegel started a journal called Kritische Journal der Philosophie. They both wrote for it until Schelling left in 1803. In 1805, the university made Hegel an unsalaried extraordinary professor. He had to write a letter to the famous poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe to protest another philosopher getting promoted before him.

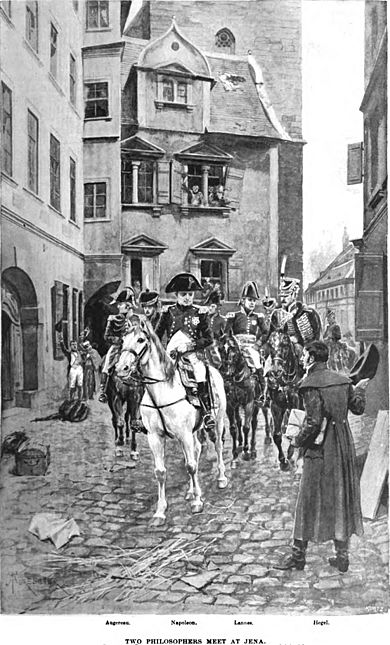

In 1807, Hegel had a son, Georg Ludwig Friedrich Fischer. His finances were tight, and he was working hard to finish his book, The Phenomenology of Spirit. He was putting the final touches on it when Napoleon's troops fought the Prussian army in the Battle of Jena–Auerstedt on October 14, 1806. Napoleon himself entered Jena the day before the battle.

Hegel wrote to his friend Friedrich Immanuel Niethammer about seeing Napoleon. He felt that Napoleon represented a "world-soul" or a great historical force. Even though the university was mostly saved, few students returned after the battle, making Hegel's money problems worse. He tried to get another professorship but couldn't find a permanent job.

In 1807, Hegel moved to Bamberg because he needed money to support his son Ludwig. He became the editor of a local newspaper, Bamberger Zeitung, which supported the French. He wrote articles praising Napoleon. Hegel enjoyed the social life in Bamberg but disliked what he saw as "old Bavaria."

In 1808, Hegel was investigated for publishing French troop movements. He asked Niethammer, who was now a high official, for help getting a teaching job. With Niethammer's help, Hegel became the headmaster of a high school (gymnasium) in Nuremberg in November 1808. He stayed there until 1816. In Nuremberg, he taught a class called "Introduction to Knowledge of the Universal Coherence of the Sciences."

In 1811, Hegel married Marie Helena Susanna von Tucher. They had two sons, Karl Friedrich Wilhelm and Immanuel Thomas Christian. During this time, Hegel published his second major work, the Science of Logic (in three parts, 1812, 1813, and 1816).

Heidelberg and Berlin (1816–1831)

Hegel received job offers from several universities and chose Heidelberg in 1816. His son Ludwig Fischer, who had been in an orphanage after his mother passed away, joined the Hegel family in 1817. In 1817, Hegel published The Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Outline, which summarized his philosophy for his students. He also started lecturing on the philosophy of art.

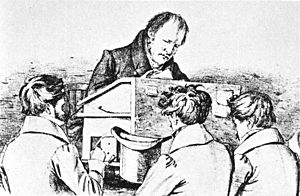

In 1818, Hegel accepted a job offer to become the philosophy professor at the University of Berlin. This position had been empty since the death of Johann Gottlieb Fichte in 1814. In Berlin, Hegel published his Philosophy of Right (1821). He spent most of his time giving lectures. His lectures on art, religion, history, and the history of philosophy were published after his death using notes from his students. Even though he wasn't a great speaker, his fame grew, and students came from all over to hear him.

Hegel and his students faced some harassment and surveillance from government officials who were against reform. He traveled to Weimar (where he met Goethe), Brussels, Leipzig, Vienna, Prague, and Paris. In his last ten years, Hegel didn't publish new books but revised his Encyclopedia (second edition in 1827, third in 1830). He also criticized a book that said laws weren't necessary.

Hegel became the university's Rector (head) in October 1829, serving until September 1830. He was upset by the riots for reform in Berlin that year. In 1831, King Frederick William III gave him an award for his service to the Prussian state.

In August 1831, a cholera epidemic reached Berlin. Hegel left the city but returned in October, thinking the illness had mostly gone away. On November 14, 1831, Hegel passed away. Doctors said he died from cholera, but it might have been another stomach illness. He was buried on November 16 in the Dorotheenstadt cemetery, next to Fichte.

Hegel's son, Ludwig Fischer, had died shortly before in Batavia while serving in the Dutch army, but Hegel never received the news. His sister Christiane died the next year. Hegel's other two sons, Karl (who became a historian) and Immanuel (who studied theology), lived long lives and protected their father's writings and letters.

Who Influenced Hegel?

When Hegel started seminary in 1788, he was a typical product of the German Enlightenment. He loved reading Rousseau and Lessing. He knew about Kant's ideas, but he was perhaps more interested in ancient Greek writers. In his early life, the Greeks, especially Plato, were most important to him.

Even though he later valued Aristotle more than Plato, Hegel always loved ancient philosophy. Its influence can be seen throughout his work. Hegel was also influenced by early German romanticism. He was concerned with how different cultures (Jewish, Greek, medieval, and modern) were united. He and his generation used the phrase "unity of life" to describe the highest good. This meant being united "with oneself, with others, and with nature." The biggest threat to this unity was division or separation.

Hegel was especially interested in love as a way to achieve "unity-in-difference." He saw this in Plato's ancient ideas and in the Christian idea of agape (selfless love). This interest, along with his religious training, continued to shape his thinking.

Hegel's philosophical system, especially its three-part structure, was also influenced by the hermetic tradition, particularly the work of Jakob Böhme. He also read widely and was influenced by Adam Smith and other thinkers on political economy.

Kant's "Critical Philosophy" showed the divisions that Hegel wanted to overcome. This led Hegel to engage with the ideas of Fichte and Schelling, as well as Spinoza. However, the influence of Johann Gottfried von Herder led Hegel to question the idea that Kant's ideas were universal. Instead, Hegel thought that reason was shaped by culture, language, and history.

Hegel's Philosophical System

Hegel's philosophy is divided into three main parts:

- The science of logic

- The philosophy of nature

- The philosophy of spirit (which includes the philosophy of nature)

This structure is similar to ancient Greek ideas and the Christian idea of the Trinity. Hegel started developing this system around 1805, but he didn't publish it completely until his 1817 Encyclopedia.

Hegel believed that the universal (general ideas) always comes first in explaining things, even if specific things come first in reality. The logic part of his system provides these universal ideas. The "logical idea" is timeless and doesn't exist separately from how it shows up in nature and spirit. Asking "when" it divides into nature and spirit is like asking "when" 12 divides into 5 and 7 – it's a misunderstanding. The logic aims to show how nature and spirit are both connected and different, overcoming the idea of a separate subject and object.

Hegel's Encyclopedia suggests that focusing on only one part of his system gives an incomplete picture. As he famously said, "The true is the whole."

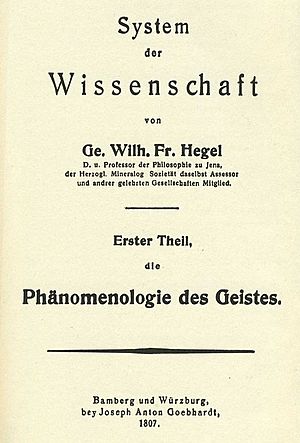

The Phenomenology of Spirit

The Phenomenology of Spirit was published in 1807. In this book, Hegel, at age 36, first showed his unique way of looking at philosophical problems after Kant. However, many people at the time didn't understand it well, and it received mostly negative reviews. Even today, the Phenomenology is known for being very complex, with difficult ideas and unusual words.

The fourth chapter of the Phenomenology includes Hegel's famous idea of the lord-bondsman dialectic. This part has been very influential. It talks about how two people try to get recognition from each other. What they learn, but don't realize yet, is that true recognition must be mutual. This means that if you don't see someone as truly human, your recognition of them doesn't count. Hegel also suggests that our self-awareness comes from how others see us, and our view of ourselves is shaped by others' views.

Hegel described The Phenomenology as both an "introduction" to his philosophy and the "first part" of his system. However, its role has been debated, and Hegel's own opinion on it changed over his life.

The book starts with simple "certainties of consciousness," like knowing "I am conscious of this object, here and now." Hegel then tries to show how these simple certainties lead to complex philosophical logic. This process is not like a story where a character learns. Instead, "we," the readers, learn from Hegel's logical explanation of how consciousness experiences things.

The journey through the book is long and difficult. Hegel called it a "path of despair" because consciousness keeps finding itself wrong. It's like testing an idea of knowledge in real experience. If the idea isn't good enough, consciousness "suffers this violence at its own hands." Hegel said you can't learn to swim without getting in the water. By testing its idea of knowledge, the Phenomenology tries to show how metaphysics (the study of reality) is built.

The Phenomenology tries to show that our thoughts always shape what we experience. It also shows that our social and mental world depends on people recognizing each other. When recognition fails, we need to look at the past to understand what we need to do now. For Hegel, this means rethinking religion as a way for modern society to reflect on what is most important to it. He believed this historical and social view helps us understand our "modern" way of thinking.

Another way to see this is that the Phenomenology continues Kant's work of exploring what reason can do. But Hegel does it historically, not just based on pure thought. He believed that reason itself has a history, and what we consider reasonable changes over time.

Walter Kaufmann praised the Phenomenology, saying that a philosopher should not just look at ideas, but also understand the human reality behind them. It's important to ask what kind of person would hold certain beliefs. Every viewpoint should be studied as a real way of existing, not just an academic idea.

The Phenomenology of Spirit teaches that looking for an outside way to find truth is pointless. The limits of knowledge are inside our own spirit. Even though our ideas can always be changed, this isn't just an imaginary exercise. Claims to knowledge must always prove themselves in real historical experience.

Even though Hegel seemed to have left the Phenomenology behind in his later years, he was planning to revise and republish it before he died. This suggests he still thought it was an important project. However, scholars still debate the exact role of the Phenomenology in his overall system.

Science of Logic

Hegel's idea of "logic" is very different from the usual meaning. For him, logic is "the science of things understood through the thoughts that used to be seen as expressing the true nature of those things." It's a deeper kind of logic than just formal rules.

There are two versions of Hegel's Logic. The first, The Science of Logic (published in parts from 1812 to 1816), is sometimes called the "Greater Logic." The second is a shorter version in his Encyclopedia, known as the "Lesser Logic." The Encyclopedia version was for students and was not meant to replace the longer book.

Hegel saw logic as a science that doesn't assume anything. It explores the most basic ways of thinking, or "categories," and forms the basis of philosophy. When you question something, you already use logic. So, logic is the only field that must always think about how it works. The Science of Logic is Hegel's attempt to do this. He said that "logic is the same as metaphysics" (the study of reality).

Hegel's metaphysics is not about guessing things beyond our experience. He agreed with Kant that any future study of reality must be open to criticism. Scholars say Hegel's way of developing and criticizing ideas from within is unique in history.

The Logic tries to show that the ideas of logic cannot be judged by anything outside of thought itself. It argues that "thought... is not a mirror of nature." But this doesn't mean these ideas are random. Hegel's categories are built into life itself and define what it means to be an "object in general."

The Logic has three main parts: "Being," "Essence," and "the Concept." The first two, "Being" and "Essence," make up the Objective Logic, which deals with overcoming old ideas about reality. The third part, "the Concept," brings these ideas together into a complete understanding of reality.

Simply put, "Being" describes ideas as they appear. "Essence" tries to explain them by looking at other forces. "The Concept" explains and unites both by looking at their inner purpose. The ideas in "Being" flow into each other. The ideas in "Essence" reflect each other. Finally, in "the Concept," thought becomes fully self-aware, and its ideas naturally grow from one to the next.

Hegel's "concept" (Begriff) is not a psychological idea. When he talks about "the Concept," he means the understandable structure of reality. When he uses "concepts" in the plural, it's closer to the everyday meaning.

Hegel's study of thought looks at how pure ideas (logical categories) differ from each other and how they depend on each other. For example, in the beginning of the Logic, Hegel says that the idea of "being, pure being—without anything else" is the same as the idea of nothing. This movement between being and nothing creates the idea of becoming.

The final idea in the Logic is "the idea." For Hegel, this term is not psychological. Following Kant, Hegel's use of "idea" goes back to Plato's concept of a perfect and universal "form." Hegel's "Idea" tries to combine the study of reality, knowledge, and values into one set of ideas.

The Logic understands that there are things in nature and spirit that cannot be known beforehand. It realizes itself only in nature and spirit, where it is "verified." This is why the Science of Logic ends with "the idea freely letting itself go" into "objectivity and external life," leading to the next part of his system, the Realphilosophie.

Philosophy of Reality (Realphilosophie)

The second part of Hegel's system, the Philosophy of Nature and of Spirit, is an ongoing historical project. He said it is "its own time understood in thoughts."

This might sound like philosophy can't change things, but it also means that philosophy is always ready to understand what is happening. Hegel believed that reality is always developing and never truly finished.

Hegel explained the connection between the logical and real parts of his system: "If philosophy does not stand above its time in content, it does so in form, because, as the thought and knowledge of that which is the substantial spirit of its time, it makes that spirit its object." This means that the philosophy of reality is "scientific" because it finds a logical, consistent form in natural and historical events.

The Philosophy of Nature

The philosophy of nature organizes the facts of natural sciences in a systematic way. It doesn't tell nature what it should be like. Some people have questioned Hegel's understanding of science, but recent studies have shown he was well-informed for his time.

One way the philosophy of nature can help science is by fighting against explanations that are too simple. For example, it would argue against trying to explain life only in chemical terms, because life is more complex.

Hegel and other "nature philosophers" wanted to bring back the idea of purpose in nature. But they said their idea of purpose was "limited to the ends observable within nature itself." This means it doesn't break Kant's rules. They argued that only by assuming there is an "organism" can we explain how the subjective (our minds) and objective (the world) interact.

A modern scholar, Dieter Wandschneider, says that today's philosophy of science has forgotten about the question of whether nature itself has laws. He suggests that philosophers of science should look back to Hegel for guidance.

Some recent scholars also believe that Hegel's ideas about nature can help us understand and deal with modern environmental problems. They point to his ideas about how nature and spirit are connected.

The Philosophy of Spirit

The German word Geist means many things. In Hegel's philosophy, Geist usually refers to the human mind and what it creates, as opposed to nature or pure logical ideas. (Some older translations use "mind" instead of "spirit.")

Hegel's idea of spirit is like Aristotle's idea of energeia (being-at-work). Spirit is not something separate from nature. It is the "highest organization and development" of nature's powers.

Hegel believed that the "essence of spirit is freedom." The Encyclopedia Philosophy of Spirit shows how this freedom develops until spirit fulfills the ancient Greek saying, "Know thyself."

Hegel's idea of freedom is not just about making random choices. It means that something, especially a person, is free if it is independent and decides for itself, not controlled by something else. It's about what Isaiah Berlin later called positive liberty.

Subjective Spirit

The Philosophy of Subjective Spirit looks at the individual human mind and what it needs for social interaction. It explores the basic nature of the human individual and the mental and practical things needed for people to interact.

This section contains some comments that we now see as racist, though they were common in Hegel's time. Hegel believed that climate, not race, was the main factor. He thought that the weather conditions where people lived limited or allowed their freedom. He was not a ""scientific" racist" because he believed that any group could improve their situation by moving to different climates. However, the racist implications of these remarks are still debated today.

Hegel divides his philosophy of subjective spirit into three parts: anthropology, phenomenology, and psychology. Anthropology deals with the "soul," which is spirit still connected to nature. Phenomenology looks at how consciousness relates to objects and how people become rational together. Psychology discusses things like attention, memory, imagination, and judgment.

Hegel used Aristotle's ideas to understand the mind-body problem. He believed that the mind doesn't act on the body like a cause and effect. Instead, the mind acts on itself as an embodied living being. It develops itself, becoming more and more self-determined. The final part, Free Spirit, develops the idea of "free will," which is key to Hegel's philosophy of right.

Objective Spirit

Hegel's philosophy of objective spirit is his social philosophy. It explains how human spirit shows itself in social and historical activities. In other words, it's about how freedom becomes part of our institutions. Scholars agree that freedom is the most important idea in Hegel's political theory. This is because it is the basis of law, the essence of spirit, and the goal of history.

This part of Hegel's philosophy is found in his 1817 Encyclopedia and more fully in his 1821 Elements of the Philosophy of Right. He also lectured on it, especially the philosophy of world history.

Hegel's Elements of the Philosophy of Right has been debated since it was published. It is not a simple defense of the absolute rule of the Prussian state. Instead, it defends "Prussia as it was meant to become under [proposed] reforms."

The German word Recht in Hegel's title doesn't have a direct English translation. It can mean a right, justice, or the law. Hegel's theory tries to bring back the idea of natural law while considering criticisms of the historical school. He argued against social contract theory and emphasized the deeper foundations of his philosophy of right.

Kenneth R. Westphal explains the structure of the Philosophy of Right:

- "Abstract Right" deals with property, its transfer, and wrongs against property.

- "Morality" deals with the rights of individuals, responsibility for actions, and theories of right based on pure reason.

- "Ethical Life" analyzes the principles and institutions of rational social life, including the family, civil society, and the state (government).

Hegel described the constitutional monarchy of his time as having three cooperating parts: democracy (rule of many in lawmaking), aristocracy (rule of few who apply laws), and monarchy (rule of one who leads all). This is like what Aristotle called a "mixed" government, designed to include the best parts of each form. The separation of powers prevents any one power from dominating others. Hegel wanted the monarch to be bound by the constitution, with limited power.

Hegel's relationship with modern liberalism is complex. He saw liberalism as important for the modern world but also thought it could harm its own values. He believed that individual goals should be measured by a larger, shared good. While he is seen as a supporter of positive liberty (freedom to achieve one's potential), he also strongly defended negative liberty (freedom from interference).

Hegel's ideal ruler was weaker than typical monarchs of his time. His democratic element was also weaker than in today's democracies. He believed in public participation but limited voting rights and followed the English two-house system, where only the lower house was elected. Nobles in the upper house, like the monarch, inherited their positions.

The final part of the Philosophy of Objective Spirit is "World History." Hegel argued that history shows a steady increase in people's ability to make their own choices ("freedom") and understand themselves ("self-knowing"). In his words: "World history is progress in the consciousness of freedom – a progress that we must comprehend conceptually."

In his Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, Hegel divided human history into three periods. In the "Oriental" world, one person (like a pharaoh) was free. In the Greco-Roman world, some people (citizens with money) were free. In the "Germanic" world (Christian Europe), all people are free.

Hegel discussed slavery in the ancient world. He said slavery happened in a "transitional phase" between a natural human existence and a truly ethical one. However, he clearly stated that slavery is wrong and goes against the idea of a rational state and the essential freedom of every person.

Some thinkers, like Alexandre Kojève and Francis Fukuyama, have interpreted Hegel to mean that history is finished once a universal idea of freedom is achieved. However, others argue that freedom can still expand in its scope (who is included) and content (what freedom means). Since Hegel's time, we have expanded freedom to include women, formerly enslaved people, and others. The International Bill of Human Rights also expands the idea of freedom beyond what Hegel wrote. Scholars also note that while Hegel's historical narratives often go from East to West, this prejudice is not central to his philosophy. They point out that freedom can move back to the East, as seen in countries like India and South Africa.

Absolute Spirit

Hegel's use of the word "absolute" can be confusing. It comes from the Latin absolutus, meaning "not dependent on anything else; self-contained, perfect, complete." For Hegel, "absolute knowing" means that the thing being known and the person knowing it are the same. The only thing that is truly absolute is something that is completely self-made. According to Hegel, this happens when spirit understands itself. The last part of his Philosophy of Spirit shows three ways of this absolute knowing: art, religion, and philosophy.

Hegel explained that these three ways of knowing are different based on how we understand them: through intuition (art), representation (religion), and comprehending thinking (philosophy). Art shows absolute truth through what we see and feel. Religion shows it through stories and symbols. Philosophy shows it through clear concepts.

These areas are ordered by how clear their concepts are, but this doesn't mean one is better than the others. Even though Hegel's discussion of absolute spirit in the Encyclopedia is short, he explained it in detail in his lectures on the philosophy of fine art, the philosophy of religion, and the history of philosophy.

Philosophy of Art

In his early works, Hegel discussed art only as it related to the "Art-Religion" of the ancient Greeks. But in 1818, he started lecturing on the philosophy of art as its own separate topic.

Hegel's lectures were titled Lectures on Aesthetics, but he made it clear his topic was "art, or, rather, fine art," not the broader idea of beauty. Some critics have wrongly said that Hegel believed art was "dead." Hegel never said this. Instead, he said that "art no longer serves our highest aims," meaning it doesn't fulfill the same role it once did in society.

Hegel's detailed study of different art forms led Ernst Gombrich to call him "the father of art history." Until recently, philosophers often ignored Hegel's lectures on art, but literary critics and art historians paid more attention.

The main goal of his philosophy of art was to explain and defend the "autonomy of art," meaning art has its own special value and unique qualities.

Hegel believed that "artistic beauty reveals absolute truth through perception." He thought that the best art gives us deep knowledge by showing us what is truly real through our senses. However, he also believed that art's sensory forms can never fully express what is completely beyond our senses. This is why art is only one of three ways of understanding absolute spirit, along with religion and philosophy.

Christianity and Hegel

Hegel was a Lutheran his whole life, and his understanding of Christianity changed over time. He always deeply appreciated the Christian idea that every person has worth and freedom.

Early Writings on Religion

Hegel's first writings on Christianity are from 1783 to 1800. He was still developing his ideas then. He was unhappy with the strict rules and traditions of Christianity and preferred the spontaneous religion of the Greeks. In The Spirit of Christianity, he tried to combine the universal moral ideas of Kant with the teachings of Jesus. He saw love as the core moral principle of the Gospel, combining Greek ideas with Kant's moral reason. Even though he didn't stick to this exact idea, uniting Greek and Christian thought remained important to him.

Christianity in The Phenomenology of Spirit

Religion is a big theme in the 1807 Phenomenology of Spirit. It appears in discussions of the "unhappiness" of the Augustinian consciousness and the struggle between the Church and the Enlightenment thinkers.

Hegel's main discussion of Christianity is in the section called "The Revelatory Religion." He used philosophical explanations of Christian ideas like the Incarnation (God becoming human) and Resurrection (Jesus rising from the dead). He claimed to show the deeper truth of Christianity, making clear what was only vaguely understood before.

The core of Hegel's interpretation of Christianity is in his view of the Trinity (God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit). He believed that God the Father had to become human (the Son), and the Son's death revealed God's true nature as Spirit. Hegel thought his own philosophical idea of spirit made the Christian idea of the Trinity clear. This, he argued, showed the philosophical truth of religion.

According to Hegel's philosophical view, Christianity doesn't require belief in ideas that can't be justified by reason. What remains is the religious community, which helps individuals and celebrates the absolute freedom of spirit.

Christianity in the Berlin Lectures

Hegel's Encyclopedia has a short section on Revealed Religion. But in his Berlin Lectures, he gave a more detailed presentation of Christianity. He called it the "consummate," "absolute," or "revelatory" religion. Transcripts of his lectures show him constantly adjusting his ideas. However, his interpretation of Christianity was still similar to what he presented in the Phenomenology, but now he could explain it more clearly.

History: Political and Philosophical

"History," according to Frederick Beiser, "is central to Hegel's idea of philosophy." Philosophy is only possible if it is historical, meaning the philosopher understands the origins, context, and development of ideas. Beiser called this a "revolution in the history of philosophy."

Hegel was more interested in the philosophy of history than in just proving history is a science. He believed that history itself has a telos (a goal or purpose), which is the growth of freedom. The more a culture understands this essential freedom of spirit, the more advanced Hegel believed it to be.

Because freedom is the essence of spirit, its growing self-awareness is a development in truth and in political life. Thinking assumes a belief in truth. The history of philosophy, as Hegel told it, is a series of developing ideas about truth.

The importance of history in Hegel's philosophy cannot be denied. German has two words for "history": Historie (narrative of facts) and Geschichte (the underlying logic of events). Hegel used the latter, focusing on a universal or philosophical history. He believed humans are historical because we internalize events, making them part of who we are. This is why the history of philosophy is part of philosophy itself. Later philosophers can understand things more deeply because of the work of those who came before them. For example, the idea of personhood now clearly includes everyone, making it contradictory to exclude anyone.

In his Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, Hegel simplified human history into three periods:

- In the "Oriental" world, one person was free (like a pharaoh).

- In the Greco-Roman world, some people (wealthy citizens) were free.

- In the "Germanic" world (Christian Europe), all people are free.

Hegel discussed slavery in the ancient world. He said it was a necessary stage between a natural human existence and a truly ethical one. However, Hegel was clear that slavery is morally wrong and goes against a rational state and the essential freedom of every individual.

Some scholars, like Alexandre Kojève and Francis Fukuyama, have interpreted Hegel to mean that history ends once a universal idea of freedom is achieved. However, others argue that freedom can still expand in its scope (who is included) and content (what freedom means). Since Hegel's time, we have expanded freedom to include women, formerly enslaved people, and others. The International Bill of Human Rights also expands the concept of freedom beyond what Hegel himself wrote.

Dialectics, Speculation, and Idealism

Dialectics and Speculation

Hegel is often associated with a "dialectical method." However, he actually called his philosophy "speculative" (spekulativ) and used "dialectical" only rarely. This is because "dialectical" often refers to the negative side of reason, where ideas show their own limits.

Hegel described correct thinking as having three parts:

- (a) abstract and intellectual (understanding things separately)

- (b) dialectical or negatively rational (seeing how ideas contradict themselves)

- (c) speculative or positively rational (finding a higher unity that includes the contradictions)

For example, "self-consciousness" is a speculative idea. It means the mind is both the subject (the one knowing) and the object (what is being known) at the same time.

Hegel's "method" is more like an "anti-method." He believed that you must understand the "self-organization" of the topic itself, its "inner necessity" and "inherent movement." He rejected outside methods that could be "applied" to any subject.

Sublation

The "dialectical" nature of Hegel's thinking often makes his views hard to explain. Instead of directly answering a question, he often rephrased it. He would show that the opposing ideas in a debate are actually false, and that parts of both ideas can be combined. This process, where true parts of opposing ideas are kept and raised to a higher level, is what Hegel called "sublation."

To "sublate" (aufheben) has three main meanings:

- 'to raise, to hold up'

- 'to cancel, abolish, destroy'

- 'to keep, save, preserve'

Hegel generally used the term with all three meanings, especially the last two. This is how apparent contradictions are overcome. His word for what is sublated is "moment" (das Moment). This means an important feature of a whole system or a key phase in a developing process. When Hegel called something "contradictory," he meant it couldn't stand on its own. It could only be understood as part of a larger whole.

Hegel believed that to think of something limited as a "moment" of the whole, rather than as a separate thing, is to see it as "idealized." Idealism, then, is the idea that limited things depend on a larger, self-sustaining whole for their existence.

Idealism

The terms "moment," "sublate," and "idealize" are key to understanding Hegel's idealism. They describe stages of thought where an object is first vaguely present, then understood in its context, and finally stands completely on its own. This is different from Kant's idealism or Berkeley's idea that reality is only in the mind. Hegel's idealism is compatible with realism (the belief that reality exists independently of our minds) and naturalism (the belief that everything can be explained by natural causes). He rejected the idea that all knowledge comes from experience alone. Hegel's main point, which he claimed to prove, is that being itself is rational.

While it's not wrong to call Hegel's philosophy "absolute idealism," this term was more connected with Schelling at the time. Hegel himself used it only a few times to describe his own work.

Hegel believed that "every philosophy is essentially idealism." This is because he thought that thinking is present at all levels of knowledge. To deny this would lead to total skepticism. So, Hegel's idealism is a form of "conceptual realism," meaning he believed that concepts are part of the structure of reality itself.

Impact and Criticisms

Hegel's ideas have had a huge impact on philosophy. In England in the late 1800s and early 1900s, a group called British idealism developed a version of absolute idealism based on Hegel's writings. Important members included J. M. E. McTaggart and R. G. Collingwood.

Other philosophers, like Marx, Dewey, and Derrida, used some of Hegel's ideas in their own philosophies. Others developed their ideas in opposition to Hegel, such as Kierkegaard and Russell. In theology, Hegel influenced thinkers like Karl Barth. Many other important figures have engaged with Hegel's philosophy.

"Right" vs. "Left" Hegelianism

Some historians divide Hegel's followers into two groups: "Right Hegelians" and "Left Hegelians." The Right Hegelians were said to be Hegel's direct students in Berlin. They supported traditional Protestant religion and the conservative politics of the time. The Left Hegelians, also known as the Young Hegelians, interpreted Hegel in a more revolutionary way. They supported atheism in religion and liberal democracy in politics. However, recent studies have questioned this simple division.

The Right Hegelians were quickly forgotten. The Left Hegelians, however, included some of the most important thinkers of the period. They focused on practical change and remained very influential, especially through the Marxist tradition.

Marxism

Among the first to criticize Hegel's system were the 19th-century German group known as the Young Hegelians. This group included Feuerbach, Marx, and Engels. Their main criticism is summed up in Marx's "Theses on Feuerbach": "The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it."

Even though some think Hegel's influence on Marx was only in his early writings, evidence shows that Hegel's ideas also shaped the structure of Marx's later work, Capital.

In the 20th century, this interpretation was further developed by critical theorists of the Frankfurt School. This happened because Hegel was seen as a possible philosophical ancestor of Marxism. Also, there was a renewed interest in Hegel's historical perspective and his dialectical method. György Lukács' book History and Class Consciousness (1923) helped bring Hegel back into Marxist studies.

Claims of Authoritarianism

Karl Popper claimed in his book The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945) that Hegel's philosophy was a hidden way to justify the absolute rule of King Frederick William III. Popper also said that Hegel's idea of history's goal was to reach a state similar to Prussia in the 1830s. Popper further suggested that Hegel's philosophy inspired the communist and fascist governments of the 20th century. However, scholars like Kaufmann and Shlomo Avineri have criticized Popper's ideas about Hegel.

Benedetto Croce said that Giovanni Gentile, a noted Italian Fascist, was "the most rigorous neo-Hegelian" but also had the "dishonor of having been the official philosopher of Fascism in Italy."

Isaiah Berlin listed Hegel as one of six thinkers who helped create modern authoritarianism and undermined liberal democracy.

Thesis–Antithesis–Synthesis

The terms "thesis–antithesis–synthesis" were mainly developed by Fichte and spread by Heinrich Moritz Chalybäus in descriptions of Hegel's philosophy. However, these descriptions have largely been shown to be incorrect.

Some scholars say this account is "only a partial understanding that needs correction." It is true that, for Hegel, "truth emerges from error" in history, and partial truths are corrected. But this description is only possible after the process has happened. The "thesis" and "antithesis" are not completely separate. If there is a "dialectical method," it's not an external one that can be "applied" to a subject.

Similarly, Stephen Houlgate argues that Hegel's "method" is strictly internal. It comes from deeply understanding the subject itself. If this leads to dialectics, it's because there's a contradiction within the object, not because of an outside method.

American Pragmatism

Hegel's influence on American Pragmatism can be seen in three periods: the late 1800s, the mid-1900s, and today. In the early days, it appeared in The Journal of Speculative Philosophy. Later, major figures like John Dewey, Charles Pierce, and William James were influenced by Hegel.

Dewey himself said that Hegel's ideas appealed to him because they "supplied a demand for unification that was doubtless an intense emotional craving." Dewey accepted much of Hegel's ideas about history and society but rejected his (likely incorrect) understanding of Hegel's "absolute knowing."

Two philosophers, John McDowell and Robert Brandom (sometimes called the "Pittsburgh Hegelians"), represent the third period of Hegel's influence on pragmatism. They openly admit Hegel's influence but don't claim to explain his views exactly as he understood them. They are also influenced by Wilfrid Sellars. McDowell is interested in challenging the idea of "the given" (the separation between concepts and intuition). Brandom focuses on developing Hegel's social view of reason and rules. These are some of the "non-metaphysical" interpretations of Hegel's thought.

Publications and Other Writings

Brackets indicate title supplied by editor; published articles are in quotes; book titles are italicized.

Bern, 1793–96

- 1793–94: [Fragments on Folk Religion and Christianity]

- 1795–96: [The Positivity of the Christian Religion]

- 1796–97: [The Oldest System-Program of German Idealism] (authorship disputed)

Frankfurt am Main, 1797–1800

- 1797–98: [Drafts on Religion and Love]

- 1798: Confidential Letters on the prior constitutional relations of the Wadtlandes (Pays de Vaud) to the City of Bern. A complete Disclosure of the previous Oligarchy of the Bern Estates. Translated from the French of a deceased Swiss [Jean Jacques Cart], with Commentary. Frankfurt am Main, Jäger. (Hegel's translation is published anonymously)

- 1798–1800: [The Spirit of Christianity and its Fate]

- 1800–02: The Constitution of Germany (draft)

Jena, 1801–07

- 1801: De orbitis planetarum; 'The Difference between Fichte's and Schelling's System of Philosophy'

- 1802: 'On the Essence of Philosophical Critique in general and its relation to the present state of Philosophy in particular' (Introduction to the Critical Journal of Philosophy, edited by Schelling and Hegel)

- 1802: 'How Commonsense takes Philosophy, Illustrated by the Works of Mr. Krug'

- 1802 'The Relation of Scepticism to Philosophy. Presentation of its various Modifications and Comparison of the latest with the ancient'

- 1802: 'Faith and Knowledge, or the Reflective Philosophy of Subjectivity in the Completeness of its forms as Kantian, Jacobian and Fichtean Philosophy'

- 1802–03: [System of Ethical Life]

- 1803: 'On the Scientific Approaches to Natural Law, its Role within Practical Philosophy and its Relation to the Positive Sciences of Law'

- 1803–04: [First Philosophy of Spirit (Part III of the System of Speculative Philosophy 1803/4)]

- 1807: The Phenomenology of Spirit

Bamberg, 1807–08

- 1807: 'Preface: On Scientific Cognition' (Preface to his Philosophical System, published with the Phenomenology)

Nürnberg, 1808–16

- 1808–16: [Philosophical Propaedeutic]

Heidelberg, 1816–18

- 1812–13: Science of Logic, Part 1 (Books 1, 2)

- 1816: Science of Logic, Part 2 (Book 3)

- 1817: 'Review of Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi's Works, Volume Three'

- 1817: 'Assessment of the Proceedings of Estates Assembly of the Duchy of Württemberg in 1815 and 1816'

- 1817: Encyclopaedia of Philosophical Sciences, 1st edition

Berlin, 1818–31

- 1820: The Philosophy of Right, or Natural Law and Political Science in Outline

- 1827: Encyclopaedia of Philosophical Sciences, 2nd rev. edn.

- 1831: Science of Logic, 2nd edn, with extensive revisions to Book 1 (published in 1832)

- 1831: Encyclopaedia of Philosophical Sciences, 3rd rev. edn

Berlin Lecture Series

- Logic 1818–31: annually

- Philosophy of Nature: 1819–20, 1821–22, 1823–24, 1825–26, 1828, 1830

- Philosophy of Subjective Spirit: 1820, 1822, 1825, 1827–28, 1829–30

- Philosophy of Right: 1818–19, 1819–20, 1821–22, 1822–23, 1824–25, 1831

- Philosophy of World History: 1822–23, 1824–25, 1826–27, 1828–29, 1830–31

- Philosophy of Art: 1820–21, 1823, 1826, 1828–29

- Philosophy of Religion: 1821, 1824, 1827, 1831

- History of Philosophy: 1819, 1820–21, 1823–24, 1825–26, 1827–28, 1829–30, 1831

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel para niños

In Spanish: Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel para niños