History of Madagascar facts for kids

The history of Madagascar is about how this unique island became what it is today. Madagascar is special because it broke away from a huge ancient landmass called Pangaea a very long time ago. Later, people from the Sunda Islands (near Indonesia) and East Africa settled there.

Because of this early isolation, thousands of unique plants and animals grew and lived on the island. Some of these are now gone, and others are in danger. When the first people arrived, trade in the Indian Ocean was busy with ships from Indonesia.

Over the last two thousand years, many different groups of people came to Madagascar. These included people from Southeast Asia (Austronesians), Africa (Bantu), Arabs, South Asians, Chinese, and Europeans. Today, most people in Madagascar are a mix of Austronesian and Bantu settlers.

Centuries of mixing created the Malagasy people. They mostly speak Malagasy, which is an Austronesian language. It has words from Bantu, Malay, Oceanic, Arabic, French, and English languages. Studies suggest that Madagascar was first settled about 1,200 years ago by a small group, mostly women from maritime Southeast Asia. The Malagasy population grew as these first settlers mixed with later arrivals.

Other groups sometimes mixed with the main population less, or they tried to keep their own separate communities.

By the Middle Ages, more than a dozen different groups had formed on the island. Each was often led by a local chief. Some groups, like the Sakalava, Merina, and Betsimisaraka, became strong kingdoms. They grew rich and powerful by trading with Europeans, Arabs, and other sailors, including pirates.

Between the 1500s and 1700s, pirates were common along Madagascar's coasts. A famous pirate colony called Libertatia was supposedly set up on Île Sainte-Marie. The Sakalava and Merina kingdoms used European trade to become stronger. They traded Malagasy slaves for European firearms and other goods. During this time, Europeans and Arabs traded with coastal communities. Europeans also tried to claim and colonize the island several times, but they failed. In the early 1800s, the British and French started competing for power in Madagascar.

By the early 1800s, King Andrianampoinimerina had brought together the large Kingdom of Imerina in the central highlands. Its capital was Antananarivo. His son, Radama I the Great, expanded the kingdom's power over other parts of the island. He was the first Malagasy ruler recognized by other countries as the ruler of the greater Merina Kingdom. After Queen Ranavalona I (who ruled from 1828 to 1861) tried to stop Christian influence, some Merina kings in the 1800s worked to modernize the country. They made strong ties with Britain, which led to European-style schools, government, and roads. Christianity, brought by the London Missionary Society, became the state religion under Queen Ranavalona II and her powerful prime minister Rainilaiarivony.

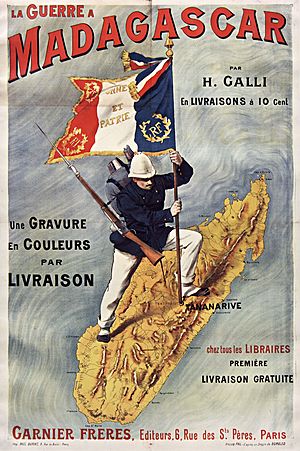

Political arguments between Britain and France in the 1880s led to Britain accepting France's power on the island. This resulted in the Malagasy Protectorate in 1890, but Madagascar's government rejected it. The French fought two Franco-Hova Wars to force Madagascar to accept their rule. They finally captured the capital in September 1895. The conflict continued with the widespread Menalamba rebellion against French rule, which was crushed in 1897. The native monarchy was ended, and the queen and her family were sent away to Reunion and then Algeria, where she died in 1917. After taking control, the French ended slavery in 1896, freeing about 500,000 slaves.

In French Madagascar, Malagasy people had to do forced labor on French-run farms. These farms made a lot of money for the colonial government. Malagasy people had few chances to get an education or skilled jobs in the colonial system. However, some basic services like schools and clinics were built in coastal areas for the first time. The capital city was greatly changed and modernized. The royal palace became a school and later a museum. Even though Malagasy people were first stopped from forming political parties, some secret nationalist groups appeared. The most important one was Vy Vato Sakelika.

Many Malagasy people were forced to fight for France in World Wars I and II. During World War II, Madagascar was controlled by the Vichy government before the British captured and occupied it in the Battle of Madagascar. At the Brazzaville Conference of 1944, Charles de Gaulle made Madagascar an overseas territory. This meant it could have representatives in the French National Assembly. When a bill for Madagascar's independence was not passed, nationalist fighters led an unsuccessful Malagasy uprising (1947–1948). During this time, the French military did terrible things that deeply hurt the people. The country became fully independent from France in 1960, as many colonies gained freedom.

Under President Philibert Tsiranana, Madagascar's First Republic (1960–1972) was a democratic system like France's. During this time, Madagascar still relied on France economically and culturally. This caused anger and led to the rotaka, which were popular movements by farmers and students. These movements brought in the socialist Democratic Republic of Madagascar under Admiral Didier Ratsiraka (1975–1992). This period was known for its economic isolation and political alliances with pro-Soviet countries. As Madagascar's economy quickly failed, living standards dropped a lot. Growing social unrest was met with harsh force by Ratsiraka's government. By 1992, free and fair elections were held, starting the democratic Third Republic (1992–2009). Under the new constitution, the public elected presidents Albert Zafy, Didier Ratsiraka, and Marc Ravalomanana. Ravalomanana was removed from power in the 2009 Malagasy political crisis by a popular movement led by Andry Rajoelina, who was then the mayor of Antananarivo. Many called this a coup. Rajoelina brought in the Malagasy constitutional referendum in 2010 and ruled Madagascar as president of the High Transitional Authority without international recognition. Elections were held on December 20, 2013, to elect a new president and bring the country back to constitutional rule.

In 2018, former president Andry Rajoelina won the presidential election. He had been president from 2009 to 2014. In January 2019, he was declared the new president.

In 2019, a measles outbreak killed 1,200 people. In 2021, Madagascar faced its worst drought in 40 years. This left over a million people in southern Madagascar without enough food, forcing thousands to leave their homes to find food.

Contents

- First People and Early Settlements (500 BCE–700 CE)

- Traders, Explorers, and New Arrivals (700–1500)

- Kingdoms and Changes (1500–1895)

- French Colonial Rule

- Fight for Freedom (1947–1960)

- Independence

- Images for kids

- See also

First People and Early Settlements (500 BCE–700 CE)

When Did People First Arrive?

The clearest signs of people living in Madagascar continuously were found at Andavakoera and date back to 490 CE. There is no proof of people living in the highlands until around 1200 CE. However, there are some scattered clues that people visited much earlier.

In 2009, scientists found bones of a giant elephant bird at Christmas River in south-central Madagascar. These bones had cut marks from human tools and were dated to 8,500 BCE. We don't know who these hunters were. Other archaeological finds, like cut marks on bones in the northwest and stone tools in the northeast, show that people visited Madagascar around 2000 BCE to gather food.

There's also a bone from a small lemur found in the southwest, with cut marks, dated to between 530 and 300 BCE. This suggests early visits, but there are no other tools or settlement signs nearby.

An ancient Egyptian expedition around Africa in 595 BCE did not see Madagascar, as they stayed close to the African coast. This suggests the island was likely empty then.

Finally, a bone from a pygmy hippo with cut marks was dated to between 60 BCE and 130 CE. This bone was found in a coastal swamp, but there are no signs of a settlement there. These findings suggest that people might have visited Madagascar for short times without staying permanently.

The First Malagasy People: From Southeast Asia

We don't have all the facts about how Madagascar was first settled. But a lot of recent research in archaeology, genetics, linguistics, and history confirms that the Malagasy people originally came from the Sunda Islands in Southeast Asia. They likely arrived on Madagascar's west coast in outrigger canoes around the beginning of our era, or even 300 years earlier.

The Borobudur Ship Expedition in 2003–2004 showed that ancient Indonesian ships could have reached Madagascar and even West Africa for trade. One possible route was directly across the Indian Ocean from Java to Madagascar. They might have stopped in the Maldives. The Malagasy language comes from a language group called Southeast Barito languages, and the Ma'anyan language is its closest relative. Malagasy also has many words borrowed from Malay and Javanese. It's known that Ma'anyan people were brought as workers and slaves by Malay and Javanese traders. These traders reached Madagascar between 50 and 500 AD.

These first pioneers are known in Malagasy stories as the Ntaolo, meaning 'first people'. It's likely these ancient people called themselves *va-waka, meaning "the canoe people." Today, the word vahoaka means 'people' in Malagasy.

The fact that the first Malagasy people came from Southeast Asia explains some common features among them. For example, many Malagasy people have an epicanthic fold (a skin fold on the eyelid), no matter their skin color or where they live on the island. This first group of people (vahoaka ntaolo) can be called the "Proto-Malagasy." They brought:

- The Malagasy language, which is spoken across the whole island. It shares many basic words with Austronesian languages from the Barito languages group, which came from South Kalimantan.

- Malagasy cultural traditions that are similar to those in Taiwan, the Pacific Islands, Indonesia, New Zealand, and the Philippines. These include old customs like burying the dead in a canoe in the sea or a lake. They also brought traditional crops like taro, banana, coconut, and sugar cane. Their traditional houses were square. They had music and musical instruments like the conch, drum, xylophone, flute, and valiha (a tube zither). They also had dances, like the "bird dance."

We don't fully understand why these Austronesians came. Madagascar might have been important in the trade of spices (like cinnamon) and wood between Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

Vazimba and Vezo: Early Settlers

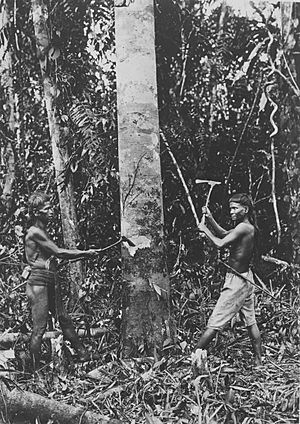

The first known large group of human settlers appeared along the southeastern coast of the island. However, the very first landing might have been on the northern coast. When they arrived, these early settlers used tavy (slash-and-burn agriculture) to clear the thick coastal rainforests for their crops. The first settlers found Madagascar's huge animals, like giant lemurs, elephant birds, giant fossa, and the Malagasy hippopotamus. These animals are now extinct because of hunting and habitat loss.

By 600 CE, some of these early settlers had moved inland. They began clearing the forests of the central highlands (Imerina). Here, they especially planted taro (saonjo) and probably rice (vary). These Vahoaka Ntaolo, who were hunters, gatherers, and farmers, decided to settle "in the forest." They are known in old stories as the Vazimba. This name comes from words meaning 'those of the forest'. For example, Rafandrana, an ancestor of the Merina royal family, was known as a Vazimba. Rafohy and Rangita, the two queens who founded the Merina royalty, were also called Vazimbas.

On the other hand, the fishermen who stayed on the southwestern coast (likely where they first landed) were probably called the Vezo. This name comes from words meaning "those of the coast." Today, Vezo is still the name of a tribe in the Southwest.

After new people arrived (see below), more food was needed as the population grew. Irrigated rice fields appeared in Betsileo country by 1600. A century later, terraced rice fields were built throughout the central highlands. Zebu cattle were brought around 1000 CE by Bantu-speaking people from the African Great Lakes region. These people kept large herds of zebu. The increasing farming and demand for zebu grazing land in the central highlands changed the area from a forest to mostly grassland by the 1600s.

Traders, Explorers, and New Arrivals (700–1500)

From the mid-700s to about 1500, the Vazimba in the interior and the Vezo clans on the coast welcomed new visitors and immigrants. These traders, who sometimes dealt in goods or slaves, came from the Middle East (like Persians, Omani Arabs, and Arab Jews, often with Bantus from Southeast Africa) and from Asia (like Gujaratis, Malays, Javanese, and Bugis). They sometimes joined the coastal Vezo and inland Vazimba clans.

Arabs from Oman (from the 7th Century)

The written history of Madagascar starts in the 600s. This is when Omanis set up trading posts along the northwest coast. They brought Islam, the Arabic writing system (used to write Malagasy in a form called sorabe alphabet), Arab astrology, and other cultural things. During this early time, Madagascar was an important trading port for the East African coast. It connected Africa to the Silk Road and served as a stop for ships coming in. There is also evidence that Bantu or Swahili sailors or traders might have sailed to Madagascar's western shores as early as the 500s and 600s.

Some Malagasy traditions say that the first Bantus and Arabs who settled in Madagascar were refugees. They were escaping the civil wars that happened after the death of Muhammad in 632.

Starting in the 900s or 1000s, Arabic and Zanzibari slave traders sailed down the Swahili coast in their dhow boats. They set up settlements on Madagascar's west coast. A notable group was the Zafiraminia, who are the traditional ancestors of the Antemoro, Antanosy, and other groups on the east coast. The last group of Arab immigrants, the Antalaotra, came from Swahili colonies. They settled in the northwest of the island (the Mahajanga area) and brought Islam to Madagascar for the first time.

Even though there were fewer Arab immigrants compared to the native Austronesians and Bantus, they left a lasting mark. Malagasy names for seasons, months, days, and coins in some areas come from Arabic. Cultural things like shared grain storage and greetings (like salama) also have Arabic roots.

New Austronesians: Malays, Javanese, Bugis, and Orang Laut (from the 8th Century)

According to old stories, new Austronesian groups (Malays, Javanese, Bugis, and Orang Laut) arrived. They were often called the "Hova" (meaning "commoner") and landed in the northwest and on the east coast. Evidence suggests the first Hova waves probably came in the 600s or later. The number of Sanskrit words in Malagasy is small compared to Indonesian languages. This means the Indonesian settlers likely came at an early stage of Hindu influence, around 400 AD.

The Hova probably came from powerful Indonesian sea kingdoms. Their leaders were called diana in the Southeast and andriana or raondriana in the Center and West. These terms mean "lord" or "master." These leaders often formed alliances with Vazimba clans:

- In the Northwest, where the Hova Orang Laut (meaning "sea people") likely set up their base for Indian Ocean trade.

- On the east coast (Betsimisaraka), where Hova leaders were also called Filo (ha) be.

- In the southeast, where the leaders ("Diana") of the Zafiraminia and Zafikazimambo clans allied with the "neo-Vezo" and created later kingdoms.

- In the west, the Maroserana family, which founded the Sakalava Kingdom, came from the Zafiraminia on the east coast.

- In the Center, repeated alliances among Hova leaders (the andriana) and Vazimba chiefs led to the Merina and Betsileo Kingdoms.

When Islam arrived, Persian and Arab traders soon took over from the Indonesians on the African coast. They eventually controlled the Comoro Islands and parts of Madagascar's coast. Meanwhile, with new naval powers like Song China and Chola South India, the Indonesian sea kingdoms quickly declined. However, Portuguese explorers still found Javanese sailors in Madagascar in the 1500s.

Bantu People (from the 9th Century)

There is proof that Bantu peoples, who were farmers and herders from East Africa, might have started moving to the island as early as the 500s and 600s. Other historical records suggest that some Bantus were descendants of Swahili sailors and traders. They used dhow boats to cross the seas to Madagascar's western shores. Some theories also say that during the Middle Ages, Arab, Persian, and new Austronesian slave traders brought Bantu people to Madagascar. These Bantus were transported by Swahili merchants to meet the foreign demand for slaves.

Years of mixing created the Malagasy people. They mainly speak Malagasy, an Austronesian language with Bantu influences. Because of this, there are many words from early Swahili in the original Malagasy language. These words are especially common in words for home and farming. For example, omby or aombe (beef) comes from the Swahili word ng'ombe.

Europeans (from 1500)

Europeans learned about Madagascar from Arab sources. For example, The Travels of Marco Polo said that "the inhabitants are Saracens, or followers of the law of Mohammed," without mentioning other people. However, everything else in the book about the island describes southeastern Africa, not Madagascar.

Europeans first made contact on August 10, 1500. This was when the Portuguese sea captain Diogo Dias saw the island after his ship got separated from a fleet going to India. The Portuguese traded with the islanders and named the island São Lourenço (Saint Lawrence). In 1666, François Caron, the head of the new French East India Company, sailed to Madagascar. The company failed to set up a colony there. Instead, they established ports on the nearby islands of Bourbon (now Réunion) and Isle de France (now Mauritius). In the late 1600s, the French set up trading posts along the east coast. On Île Sainte-Marie, a small island off Madagascar's northeastern coast, Captain Misson and his pirate crew supposedly founded the famous pirate utopia of Libertatia in the late 1600s. From about 1774 to 1824, Madagascar was a favorite place for pirates. Many European sailors were shipwrecked on the island's coasts. One of them was Robert Drury, whose journal is one of the few written descriptions of life in southern Madagascar during the 1700s. Sailors sometimes called Madagascar "Island of the Moon."

European Attempts to Settle

By the 1400s, Europeans had taken control of the spice trade from Muslim traders. They did this by sailing around the Cape of Good Hope to India, avoiding the Middle East. The Portuguese sailor Diogo Dias was the first European to land on Madagascar in 1500. Over the next 200 years, the English and French tried (and failed) to set up settlements on the island.

Diseases, hostile Malagasy people, and the harsh, dry climate of southern Madagascar quickly ended the English settlement near Toliara in 1646. Another English settlement in the north, on Île Sainte-Marie, ended in 1649. The French colony at Tôlanaro (Fort Dauphin) lasted a little longer, for thirty years. On Christmas night in 1672, local Antanosy tribesmen attacked. They might have been angry because fourteen French soldiers had recently divorced their Malagasy wives to marry fourteen French orphan women sent to the colony. The Antanosy killed the fourteen grooms and thirteen of the brides. The Antanosy then surrounded the fort at Tôlanaro for eighteen months. A French East India Company ship rescued the thirty surviving men and one widow in 1674.

In 1665, François Caron, the Director General of the new French East India Company, sailed to Madagascar. The Company failed to create a colony on Madagascar. Instead, it set up ports on the nearby islands of Bourbon and Île-de-France (today's Réunion and Mauritius). In the late 1600s, the French set up trading posts along the east coast.

Pirates and Slave Traders

Between 1680 and 1725, Madagascar became a stronghold for pirates. Many sailors were shipwrecked and stranded on the island. Those who survived either settled with the local people or joined French or English colonies or pirate groups, becoming pirates themselves. One such case was Robert Drury, whose journal gives a rare look into southern Madagascar in the 1700s.

Famous pirates like William Kidd, Henry Every, John Bowen, and Thomas Tew used Antongil Bay and Île Sainte-Marie (a small island off the northeast coast) as their bases. These pirates robbed merchant ships in the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the Persian Gulf. They stole silks, cloth, spices, and jewels from ships going to Europe. Ships going the other way (to India) lost their coins, gold, and silver. The pirates also robbed Indian cargo ships and ships from the French, English, and Dutch East India Companies. Pilgrim fleets sailing between India and the Arabian Peninsula were a favorite target because wealthy Muslim pilgrims often carried jewels. Merchants in India, Africa, and Réunion were willing to buy the stolen goods. The sailors on merchant ships, who were paid little, often didn't fight back, as they had little reason to risk their lives. Pirates often recruited new crew members from the ships they robbed.

Before Europeans arrived, some Malagasy tribes sometimes fought wars to capture and enslave prisoners. They either sold these slaves to Arab traders or kept them as workers. After European slave traders arrived, human slaves became more valuable. Coastal tribes in Madagascar then started fighting each other more often to get prisoners for the profitable slave trade. Instead of spears, they fought with muskets, musket-balls, and gunpowder, which they got from Europeans. These wars were fierce and brutal. The Betsimisaraka in eastern Madagascar had more firearms than anyone else because of their connection to pirates. They overpowered their neighbors and even raided the Comoro Islands. The Sakalava people on the west coast also had access to guns because of their links to the slave trade.

Today, the people of Madagascar are a mix of the first settlers (the vahoaka ntaolo Austronesians, including Vazimba and Vezo) and those who arrived later (new Austronesians called Hova, Persians, Arabs, Africans, and Europeans).

Genetically, the original Austronesian heritage is spread fairly evenly across the island. Researchers have found a "Polynesian marker" everywhere. This marker shows an old link between Austronesian populations before the big migrations to the islands of Polynesia and Melanesia. This suggests a common origin for the Proto-Malagasy vahoaka ntaolo (who went west to Madagascar) and the ancestors of today's Polynesians (who went east to the Pacific Islands) between 500 BCE and 1 CE.

Kingdoms and Changes (1500–1895)

The Rise of Great Kingdoms

The new immigrants who arrived during the Middle Ages were a small group. However, their culture, politics, and technology greatly changed the world of the early Vazimba and Vezo. This led to big changes in the 1500s, starting the Malagasy feudal era.

On the coasts, the mixing of East Asians, Middle Easterners, Bantus, and Portuguese led to the creation of kingdoms. These included the Antakarana, Boina, Menabe, and Vezo on the west coast. In the south, there were the Mahafaly and Antandroy. On the east coast, kingdoms like the Antesaka, Antambahoaka, Antemoro, Antanala, and Betsimisaraka formed.

In the interior, different early Vazimba clans in the central highlands, called the Hova by coastal groups, fought for power. This led to the creation of the Merina, Betsileo, Bezanozano, Sihanaka, Tsimihety, and Bara kingdoms.

The birth of these kingdoms changed the political structure of the old Vahoaka Ntaolo world. But for the most part, the common language, customs, traditions, religion, and economy stayed the same.

Among the Central Kingdoms, the most important were the Betsileo kingdoms (Fandriana, Fisakana, Manandriana, Isandra) in the south, and the Merina kingdoms in the north. These were finally united in the early 1800s by Andrianampoinimerina. His son and successor, Radama I (who ruled from 1810–1828), opened his country to foreign influence. With British support, he extended his power over much of the island. From 1817, the central Merina, Betsileo, Bezanozano, and Sihanaka kingdoms, united by Radama I, became known to the outside world as the Kingdom of Madagascar.

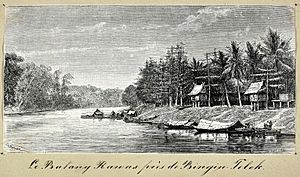

The Sakalava Kingdom

The island's western chiefs started to gain power through trade with their neighbors in the Indian Ocean. First, they traded with Arab, Persian, and Somali traders who connected Madagascar with East Africa, the Middle East, and India. Later, they traded with European slave traders. The wealth from this trade helped create a state system ruled by powerful regional kings called the Maroserana. These kings adopted the cultural traditions of the people in their lands and expanded their kingdoms. They gained a special, almost divine, status, and new noble and artisan classes were created. Madagascar became an important trading port for other Swahili city-states like Sofala, Kilwa, Mombasa, and Zanzibar. By the Middle Ages, large chiefdoms controlled big areas of the island. These included the Betsimisaraka alliance on the eastern coast and the Sakalava chiefdoms of Menabe (around the town of Morondava) and Boina (around the city of Mahajanga). The Sakalava's influence spread across what are now the provinces of Antsiranana, Mahajanga, and Toliara.

According to local stories, the Sakalava kingdom was founded by Maroseraña princes from Fiherenana (now Toliara). They quickly took control of neighboring princes, starting in the south. The true founder of Sakalava power was Andriamisara. His son, Andriandahifotsy (around 1610–1658), then extended their power north, past the Mangoky River. His two sons, Andriamanetiarivo and Andriamandisoarivo, pushed even further north into the Tsongay region (now Mahajanga). Around that time, the empire started to split into a southern kingdom (Menabe) and a northern kingdom (Boina). More splits happened, even as the Boina princes continued to expand into the far north, into Antankarana country.

We know about the Sakalava rulers of this time from the writings of Europeans like Robert Drury, James Cook, Barnvelt (1719), and Valentyn (1726).

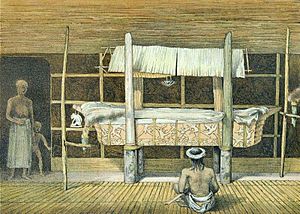

The Merina Monarchy

King Andrianampoinimerina (1785–1810) and his son, Radama I (1810–1828), managed to unite almost all of Madagascar under Merina rule. These kings and their successors came from a line of ancient Merina royalty who had ruled the lands of Imerina in the central Highlands of Madagascar since at least the 1500s. Even before they took over the whole island, the political and cultural actions of Merina royalty left a strong mark on what it means to be Malagasy today.

By taking control of most of the Highlands, Andrianampoinimerina became the first Merina monarch to be seen as a king of Madagascar. The island continued to be ruled by Merina monarchs until the last one, Ranavalona III, was removed from power and sent away to Algeria by French forces. The French conquered and colonized the island in 1895.

King Andrianampoinimerina

Andrianampoinimerina, the grandson of King Andriambelomasina, successfully united the divided Merina kingdom. He did this through diplomacy, smart political marriages, and successful military campaigns against rival princes. Andrianampoinimerina stood out from other kings by writing down laws and overseeing the building of dikes and trenches. These helped increase the amount of farmland around his capital at Antananarivo, which successfully ended the famines that had troubled Imerina for decades. The king famously said: Ny ranomasina no valapariako ("the sea is the boundary of my rice-field"). By the time he died in 1810, he had conquered the Bara and Betsileo highland tribes, setting the stage for his kingdom to expand to the island's coasts.

King Radama I (1810–1828)

Andrianampoinimerina's son, Radama I (Radama the Great), became king during a time of big changes in Europe that affected Madagascar. After Napoléon was defeated in 1814/1815, power in Europe and overseas shifted to Britain. The British wanted to control the trade routes in the Indian Ocean. They had captured the islands of Réunion and Mauritius from the French in 1810. Although they gave Réunion back to France, they kept Mauritius as a naval base to maintain trade links throughout the British Empire. The governor of Mauritius tried to win Madagascar away from French control. He recognized Radama I as King of Madagascar. This diplomatic move was meant to show that the island was sovereign and prevent any European powers from claiming it.

Radama I signed agreements with the United Kingdom to outlaw the slave trade and allow Protestant missionaries into Madagascar. As a result, Protestant missionaries from Britain spread British influence in Madagascar. Outlawing the slave trade also hurt Réunion's economy by taking away slave laborers for France's sugar plantations. In return for stopping the slave trade, Madagascar received "The Equivalent." This was an annual payment of gold, silver, gunpowder, flints, muskets, and 400 surplus British Army uniforms. The governor of Mauritius also sent military advisors who sometimes led Merina soldiers in battles against the Sakalava and Betsimisaraka. In 1824, after defeating the Betsimisaraka, Radama I declared, "Today, the whole island is mine! Madagascar has but one master." The king died in 1828 while leading his army on a mission against the Betsimisaraka.

The 33-year rule of Queen Ranavalona I, who was Radama I's widow, saw the Kingdom of Madagascar grow as it conquered neighboring states. She also worked hard to keep Madagascar's culture and political independence strong against growing foreign influence. The queen rejected the agreements Radama I had signed with Britain. In 1835, after making a royal rule against practicing Christianity in Madagascar, she sent British missionaries away from the island. She also started to persecute Christians who would not give up their religion. Malagasy Christians remembered this time as ny tany maizina, or "the time when the land was dark." During her rule, constant warfare, disease, slavery, difficult forced labor, and harsh measures of justice led to many deaths among soldiers and civilians. Madagascar's population dropped from 5 million in 1833 to 2.5 million in 1839.

Unknown to the queen, her son and heir, the crown-prince (who would become Radama II), secretly attended Roman Catholic services. The young man grew up influenced by French people in Antananarivo. In 1854, he wrote a letter to Napoléon III inviting France to invade and help Madagascar. On June 28, 1855, he signed the Lambert Charter. This document gave Joseph-François Lambert, a French businessman, the special right to develop all minerals, forests, and empty land in Madagascar. In return, the Merina monarchy would get a 10-percent payment. In later years, the French would use the Lambert Charter and the prince's letter to Napoléon III to explain the Franco-Hova Wars and why they took over Madagascar as a colony. In 1857, the queen discovered a plan by her son and French people in the capital to remove her from power. She immediately expelled all foreigners from Madagascar, but spared her son. Ranavalona died in 1861.

King Radama II (1861–1863)

In his short two years as king, Radama II reopened trade with Mauritius and Réunion. He invited Christian missionaries and foreigners to return to Madagascar and brought back most of Radama I's reforms. However, his open policies angered the nobles. So, Rainivoninahitriniony, the prime minister, planned a coup where Radama II was killed.

Queen Rasoherina (1863–1868)

A group of nobles led by Rainilaiarivony approached Rabodo, Radama II's widow, the day after her husband's death. They gave her conditions for becoming queen. These included stopping trials by ordeal and the monarchy protecting freedom of religion. Rabodo was crowned queen on May 13, 1863, taking the name Rasoherina. She ruled until her death on April 1, 1868.

The Malagasy people remember Queen Rasoherina for sending ambassadors to London and Paris and for stopping Sunday markets. On June 30, 1865, she signed an agreement with the United Kingdom. This gave British citizens the right to rent land and property on the island and to have an ambassador living there. With the United States, she signed a trade agreement that also limited the import of weapons and the export of cattle. Finally, with France, the queen signed a peace agreement between her family and the family of the Emperor of France. Rasoherina married her Prime Minister, Rainivoninahitriniony. But public anger against his role in Radama II's murder soon forced him to resign and be sent away to Betsileo country. She then married his brother, Rainilaiarivony, who was head of the army when Radama II was killed. Rainilaiarivony was promoted to Prime Minister after his older brother resigned. Rainilaiarivony would secretly rule Madagascar for the remaining 32 years of the Merina monarchy, marrying each of the last three queens of Madagascar.

In 1869, Queen Ranavalona II, who had been taught by the London Missionary Society, was baptized into the Church of England. She then made the Anglican faith the official state religion of Madagascar. The queen had all the sampy (traditional royal idols) burned in public. Catholic and Protestant missionaries arrived in large numbers to build churches and schools. Queen Ranavalona II's reign was the peak of British influence in Madagascar. British goods and weapons arrived on the island through South Africa.

Her public crowning as queen happened on November 22, 1883, and she took the name Ranavalona III. Her first act was to confirm Rainilaiarivony and his group in their positions. She also promised to deal with the French threat.

End of the Monarchy

France was angry that the Lambert Charter was canceled and wanted to get back property taken from French citizens. So, France invaded Madagascar in 1883. This became known as the first Franco-Hova War (Hova was a name for the Merina nobles). At the end of the war, Madagascar gave Antsiranana (Diégo Suarez) on the northern coast to France. It also paid 560,000 gold francs to the heirs of Joseph-François Lambert. Meanwhile, in Europe, diplomats had made an agreement. Britain, to control the Sultanate of Zanzibar, gave up its rights over the island of Heligoland to Germany. It also gave up all claims of influence in Madagascar to France. This agreement meant the end of Madagascar's political independence. Rainilaiarivony had been successful in playing the European powers against each other, but now France could act without fear of British support for Madagascar.

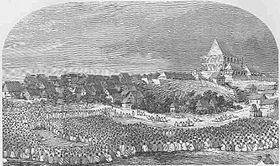

In 1895, a French military group landed in Mahajanga (Majunga). They marched along the Betsiboka River to the capital, Antananarivo. They surprised the city's defenders, who had expected an attack from the much closer east coast. Twenty French soldiers died fighting, and 6,000 died from malaria and other diseases before the second Franco-Hova War ended. In 1896, the French Parliament voted to take over Madagascar. The 103-year-old Merina monarchy ended, and the royal family was sent away to Algeria.

Modernization of the Kingdom (1817–1895)

The Kingdom of Madagascar continued to change throughout the 1800s, becoming a more modern state.

Before Radama I, the Malagasy language was written using a script called sorabe. In 1820, under the guidance of David Jones, a Welsh missionary, Radama I created a new Malagasy Latin alphabet with 21 letters. This replaced the old sorabe alphabet. By 1830, the Bible was the first book written in this new Malagasy Latin alphabet. It is the oldest complete translation of the Bible into a language from sub-Saharan Africa.

The United States and the Kingdom of Madagascar signed a trade agreement in 1867. After this, Queen Rasoherina and Prime Minister Rainilaiarivoy exchanged gifts with President Andrew Johnson. A treaty of peace, friendship, and trade was then signed in 1881.

During the rule of Ranavalona I, early attempts at industrialization happened from 1835. Under the direction of the French man Jean Laborde (who survived a shipwreck), they started making soap, porcelain, metal tools, and firearms (rifles, cannons, etc.).

In 1864, Antananarivo opened its first hospital and a modern medical school. Two years later, the first newspaper appeared. A scientific journal in English (Antananarivo Annual) was published from 1875. In 1894, just before French colonial rule began, the kingdom's schools, mostly run by Protestant missions, had over 200,000 students.

French Colonial Rule

In 1750, the ruler of the Betsimisaraka Kingdom gave the island Nosy Boraha (Île Sainte-Marie) to the Kingdom of France. However, in 1752, the French colonists were killed when the local people rebelled. France left the settlement empty for about fifty years until returning in 1818.

In 1840, Tsiomeko, the ruler of Nosy Be island, accepted French protection. The French took control of the island in 1841, and in 1849, an attempt to expel them failed.

In the Berlin Treaty, the British agreed to France's claims to power over Madagascar. After the first Franco-Hova War, an agreement between France and Madagascar was signed on December 17, 1885, by Queen Ranavalona III. This gave France control over the Diego-Suarez bay and surrounding area, as well as the islands of Nosy-Be and Île Sainte-Marie.

Disagreements about how to carry out this agreement led to the French invasion of 1895. At first, there was little resistance. The power of Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony, who had been in charge since 1864, had become very unpopular with the public.

The British accepted France's control over Madagascar as a Malagasy Protectorate in 1890. In return, Britain's control over Zanzibar was recognized, and it was part of a larger agreement about areas of influence. France's first goal was to keep the protectorate to control the island's economy and foreign relations. But later, the start of the Menalamba rebellion and the arrival of General Gallieni in 1896 led to the colonization of the island. The queen was sent away to Algeria.

In 1904–1905, Madagascar saw a large uprising by various tribes and leaders. Among them, Kotavy, a former French corporal who joined the rebels, played a very important role.

Malagasy troops fought for France in World War II in France, Morocco, and Syria. Before the Final Solution was put into action, Nazi Germany had considered the Madagascar Plan. This plan would have moved European Jews to Madagascar. After France fell to the Germans in 1940, the Vichy government ruled Madagascar until 1942. Then, British and Commonwealth troops occupied the strategic island in the Battle of Madagascar. The United Kingdom handed control of the island to Free French Forces in 1943.

Fight for Freedom (1947–1960)

In 1948, when French power was weak, the French government put down the Madagascar revolt, a nationalist uprising.

The French later set up new institutions in 1956 under the Loi Cadre (Overseas Reform Act). Madagascar then moved peacefully towards independence. The Malagasy Republic, declared on October 14, 1958, became an independent state within the French Community. On March 26, 1960, France agreed to Madagascar becoming fully independent. On June 26, 1960, Madagascar became an independent country, and Philibert Tsiranana became its first president.

Independence

First Republic (1960–1972)

Tsiranana's rule meant things largely continued as before, with French settlers still holding powerful positions. Unlike many of France's former colonies, the Malagasy Republic strongly resisted moves towards communism.

In 1972, protests against these policies grew strong, and Tsiranana had to step down. He gave power to General Gabriel Ramanantsoa of the army and his temporary government. This new government changed previous policies to have closer ties with the Soviet Union.

On February 5, 1975, Colonel Richard Ratsimandrava became the President of Madagascar. After just six days as head of the country, he was killed in an assassination while driving from the presidential palace to his home. Political power then went to Gilles Andriamahazo.

Second Republic (1972–1991)

On June 15, 1975, Lieutenant-Commander Didier Ratsiraka (who had been foreign minister) came to power in a coup. Elected president for a seven-year term, Ratsiraka moved Madagascar further towards socialism. He nationalized much of the economy and cut all ties with France. These policies sped up the decline in Madagascar's economy that had started after independence. French immigrants left the country, leading to a shortage of skilled workers and technology. Ratsiraka's first seven-year term as president continued after his party became the only legal party in the 1977 elections.

In the 1980s, Madagascar moved back towards France. It gave up many of its communist-inspired policies in favor of a market economy, though Ratsiraka still held onto power.

Eventually, opposition from both inside and outside the country forced Ratsiraka to reconsider his position. In 1992, the country adopted a new and democratic constitution.

Third Republic (1991–2002)

The first multi-party elections happened in 1993, with Albert Zafy defeating Ratsiraka. Even though Zafy strongly supported a free-market economy, he ran on a platform that criticized the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. During his presidency, the country struggled to follow IMF and World Bank guidelines.

As president, Zafy was frustrated by the limits the new constitution placed on his powers. His desire for more executive power put him in conflict with the parliament, led by Prime Minister Francisque Ravony. Zafy eventually gained the power he wanted. However, he was later removed from office by the parliament in 1996 for breaking the constitution by refusing to pass specific laws.

The elections that followed saw less than 50% of people vote. Unexpectedly, Didier Ratsiraka was re-elected. He moved the country further towards capitalism. The influence of the IMF and the World Bank led to widespread privatisation of state-owned businesses.

Opposition to Ratsiraka started to grow again. Opposition parties boycotted provincial elections in 2000. The 2001 presidential election caused more controversy. The opposition candidate Marc Ravalomanana claimed victory after the first round in December, but the current president rejected this. In early 2002, supporters of both sides took to the streets, and violent clashes occurred. Ravalomanana claimed that fraud had happened in the polls. After a recount in April, the High Constitutional Court declared Ravalomanana president. Ratsiraka continued to dispute the result, but his opponent gained international recognition. Ratsiraka had to go into exile in France, though forces loyal to him continued activities in Madagascar.

After Ratsiraka

Ravalomanana's I Love Madagascar party won a huge victory in the December 2001 elections. He survived an attempted coup in January 2003. He used his power to work closely with the IMF and the World Bank to fix the economy, end corruption, and help the country reach its potential.

Ratsiraka was put on trial (without him being there) for embezzlement. He was accused of taking $8 million of public money with him into exile. The court sentenced him to ten years of hard labour.

Ravalomanana is praised for improving the country's infrastructure, like roads, and for making improvements in education and health. However, he has been criticized for not making enough progress against poverty. People's ability to buy things is said to have decreased during his time in office. On November 18, 2006, his plane had to change course from Madagascar's capital. This was after reports of a coup happening in Antananarivo and shooting near the airport. However, this alleged coup attempt was not successful.

Ravalomanana ran for a second term in the presidential election held on December 3, 2006. According to official results, he won the election with 54.79% of the vote in the first round. His best results were in Antananarivo Province, where he received 75.39% of voter support. He was sworn in for his second term on January 19, 2007.

Ravalomanana dissolved the National Assembly in July 2007, before its term ended. This followed a constitutional referendum earlier that year. Ravalomanana said that a new election needed to be held so that the National Assembly would reflect the changes made in this referendum.

He became involved in a political problem after he closed the TV station belonging to Antananarivo mayor Andry Rajoelina. In January 2009, protests that turned violent were organized and led by Andry Rajoelina. He was the mayor of the capital city of Antananarivo and a strong opponent of President Ravalomanana.

The situation changed greatly on March 10, 2009. Army leaders forced the recently appointed defense secretary to resign. (The previous one had resigned after killings by the presidential guard on February 7, 2009). They also announced that they gave the opposing sides 72 hours to talk and find a solution to the crisis before they would take further action. This happened after the leaders of the main military camp had announced a day earlier that they would no longer follow orders from the presidency. They said their duty was to protect the people, not to oppress them, as some military groups had done.

On March 16, 2009, the army took control of the presidential palace in the center of Antananarivo. Ravalomanana was not in the palace at the time. He gave his resignation to the army, which then decided to hand over power to his strong political rival, Andry Rajoelina. The second round of the delayed presidential elections was held in December 2013, and the results were announced in January 2014. The winner and next president was Hery Rajaonarimampianina. He was supported by Rajoelina, who led the 2009 coup and was still a very influential political figure.

In 2018, the first round of the presidential election was held on November 7, and the second round was held on December 10. Three former presidents and the most recent president were the main candidates. Former president Andry Rajoelina won the second round of the elections. He had previously been president from 2009 to 2014. Former president Marc Ravalomanana lost the second round and did not accept the results, claiming fraud. Ravalomanana was president from 2002 to 2009. The most recent president, Hery Rajaonarimampianina, received very little support in the first round. In January 2019, the High Constitutional Court declared Rajoelina the winner of the elections and the new president.

In 2019, an epidemic of measles killed 1,200 people.

In 2021, Madagascar's worst drought in 40 years left more than a million people in southern Madagascar without enough food. This forced thousands of people to leave their homes to search for food.

Images for kids

-

The taro (saonjo in Malagasy) was a main food for the early Austronesians.

-

Map of Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands (1502).

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Madagascar para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Madagascar para niños

- Ethnic groups of Madagascar

- History of Africa

- History of Southern Africa

- List of Imerina monarchs

- List of presidents of Madagascar

- Politics of Madagascar

- Antananarivo history and timeline

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |