Maria Callas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Maria Callas

|

|

|---|---|

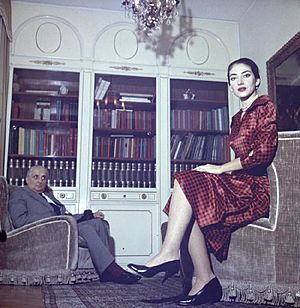

Callas in 1958

|

|

| Born |

Maria Anna Sophia Cecilia Kalogeropoulou

December 2, 1923 New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | September 16, 1977 (aged 53) Paris, France

|

| Education | Athens Conservatoire |

| Occupation | Soprano |

| Spouse(s) |

Giovanni Battista Meneghini

(m. 1949; div. 1959) |

| Partner(s) | Aristotle Onassis (1959–1968) |

| Awards | Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award |

Maria Callas (born Maria Anna Cecilia Sophie Kalogeropoulou; December 2, 1923 – September 16, 1977) was an American-born Greek soprano singer. She became one of the most famous and important opera singers of the 20th century. Many people praised her bel canto (beautiful singing) technique, her wide-ranging voice, and her powerful acting. Her performances included classical operas, bel canto operas by Donizetti, Bellini, and Rossini, and works by Verdi and Puccini. Early in her career, she also sang in operas by Wagner. Because of her amazing musical and acting skills, she was called La Divina, meaning "the Divine one."

Maria was born in Manhattan, New York City, to parents who had moved from Greece. She began her musical training in Greece at age 13 and later started her career in Italy. She faced challenges like poverty during wartime in the 1940s and severe near-sightedness that made it hard to see on stage. Later in her career, she lost a lot of weight, which some believe affected her voice.

The news often reported on Callas's strong personality, her supposed competition with another singer named Renata Tebaldi, and her relationship with Greek shipping businessman Aristotle Onassis. Even though her personal life was often in the spotlight, her artistic achievements were huge. Leonard Bernstein called her "the Bible of opera." Her influence is still strong today; in 2006, Opera News magazine said she was "still the definition of the diva as artist—and still one of classical music's best-selling vocalists."

Contents

- Early Life and Family Background

- Maria Callas's Musical Education

- Starting Her Opera Career in Greece

- Her Main Opera Career Begins

- Maria Callas's Weight Loss

- Her Unique Voice

- Maria Callas as an Artist

- Callas and Tebaldi: A Friendly Rivalry?

- Changes in Maria Callas's Voice

- Later Years and Passing Away

- Operas Maria Callas Performed

- Notable Recordings of Maria Callas

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Family Background

Maria Callas's Childhood in New York

Maria Callas was born on December 2, 1923, at Flower Fifth Avenue Hospital in Manhattan, New York City. Her birth name was Sophie Cecilia Kalos, but she was christened Maria Anna Cecilia Sofia Kalogeropoulos. Her parents were George Kalogeropoulos and Elmina Evangelia "Litsa" Demes, both from Greece. Maria's father, George, shortened their family name to "Kalos" and then to "Callas" to make it easier to use.

George and Litsa Callas had different personalities. George was relaxed and not very interested in the arts. Litsa was lively and wanted to be successful in society and the arts, but her parents had stopped her from pursuing this dream. Litsa's father had warned her not to marry George, but she didn't listen. Their marriage became more difficult over time. They had two other children: a daughter named Yakinthi (Jackie) born in 1917, and a son named Vassilis born in 1920. Vassilis sadly died from meningitis in 1922.

In 1923, Litsa became pregnant again, and George decided to move the family to the United States. They first lived in Astoria, Queens. Litsa was hoping for a son, and she was very disappointed when Maria was born, so much so that she didn't look at her new baby for four days. Maria was christened three years later in 1926. When Maria was about four years old, George Callas opened his own pharmacy, and the family settled in Washington Heights, Manhattan.

Around age three, Maria started showing musical talent. Her mother, Litsa, noticed Maria's voice and began to encourage her to sing. Maria later remembered, "I was made to sing when I was only five, and I hated it." George was not happy with the pressure put on young Maria to sing. The family's marriage continued to struggle, and in 1937, Litsa decided to return to Athens, Greece, with her two daughters.

Maria's Relationship with Her Mother

Maria's relationship with her mother, Litsa, became even more difficult during their years in Greece. When Maria became famous, their relationship was often talked about in public. A 1956 Time magazine story focused on it, and Litsa later wrote a book called My Daughter Maria Callas in 1960.

In 1957, Maria told a radio host, "There must be a law against forcing children to perform at an early age. Children should have a wonderful childhood. They should not be given too much responsibility."

Maria tried to improve things with her mother by taking Litsa with her on a trip to Mexico in 1950. However, this only brought back their old disagreements, and they never met again after that trip. After receiving many angry letters from Litsa, Maria stopped communicating with her mother completely.

Maria Callas's Musical Education

Maria Callas received her musical training in Athens, Greece. At first, her mother tried to enroll her in the famous Athens Conservatoire, but Maria's voice was not yet trained enough, and she was not accepted.

In the summer of 1937, Maria's mother took her to Maria Trivella at the younger Greek National Conservatoire. Trivella agreed to teach Maria for a small fee. Soon, Trivella realized that Maria was not an contralto (a lower female voice), as she had been told, but a dramatic soprano (a higher, powerful female voice). They then worked on making her voice higher and lighter. Trivella remembered Maria as a very dedicated student who would practice for hours.

On April 11, 1938, Maria made her first public appearance, singing a duet from Tosca. Maria later said that Trivella taught her how to breathe correctly and how to use her voice. However, Maria also gave credit to her next teacher, the Spanish coloratura soprano Elvira de Hidalgo, for helping her develop her lower "chest voice."

Maria studied with Trivella for two years. Then, her mother arranged another audition at the Athens Conservatoire with de Hidalgo. Maria sang a difficult song from Weber's Oberon. De Hidalgo remembered hearing "stormy, amazing sounds, not yet controlled but full of drama and feeling." She immediately agreed to teach Maria. On April 2, 1939, Maria sang the part of Santuzza in a student show of Mascagni's Cavalleria rusticana at the Greek National Opera. In the fall of that year, she officially joined Elvira de Hidalgo's class at the Athens Conservatoire.

De Hidalgo later called Maria "a phenomenon." Maria herself said she would go to the conservatoire at 10 in the morning and stay for 10 hours, "devouring music." She explained that even from the least talented student, she could learn something new.

Starting Her Opera Career in Greece

After performing as a student, Maria Callas began singing smaller roles at the Greek National Opera. Her teacher, Elvira de Hidalgo, helped her get these roles, which allowed Maria to earn a small salary. This money helped her and her family during the difficult war years.

Maria made her professional debut in February 1941, in a small role in Boccaccio. Other singers noticed her amazing talent even during rehearsals. Some established sopranos were jealous and tried to stop her from performing. Despite these challenges, Maria continued to sing.

In August 1942, she made her debut in a main role as Tosca. She then sang the role of Marta in Tiefland, which received excellent reviews. After these performances, even her critics started calling her "The God-Given." A fellow singer, Anna Remoundou, who used to be a rival, wondered if Maria's talent was truly "divine." Maria then sang Santuzza again and performed in O Protomastoras at the ancient Odeon of Herodes Atticus theatre.

In August and September 1944, Maria performed as Leonore in a Greek version of Beethoven's Fidelio. A German critic who saw the show called it Maria's "greatest triumph."

After Greece was freed from occupation, de Hidalgo advised Maria to go to Italy to build her career. Maria gave several concerts in Greece. Then, against her teacher's advice, she returned to America to see her father and continue her career there. When she left Greece on September 14, 1945, just before her 22nd birthday, Maria had performed in 56 shows in seven operas and about 20 concerts. Maria believed her time in Greece was the foundation of her musical and acting training, saying, "When I got to the big career, there were no surprises for me."

Her Main Opera Career Begins

After returning to the United States in September 1945, Maria Callas went to many auditions. In December, she auditioned for Edward Johnson, the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera. He was impressed, saying she had an "Exceptional voice—ought to be heard very soon on stage."

Maria said the Metropolitan Opera offered her roles in Madama Butterfly and Fidelio, to be sung in English in Philadelphia. She turned them down because she felt she was too heavy for Butterfly and didn't like the idea of opera in English. Edward Johnson later confirmed that a contract was offered, but Maria didn't like the terms, which he admitted were for a beginner.

Italy, Marriage, and a Key Mentor

In 1946, Maria was supposed to open the opera house in Chicago as Turandot, but the company closed before it could begin. A singer named Nicola Rossi-Lemeni knew that conductor Tullio Serafin was looking for a dramatic soprano for La Gioconda at the Arena di Verona. He recommended Maria, saying she was "amazing—so strong physically and spiritually; so certain of her future."

This role was Maria's first performance in Italy. In Verona, Maria met Giovanni Battista Meneghini, an older, wealthy businessman. They married in 1949, and he managed her career until 1959, when their marriage ended. Meneghini's support gave Maria the time she needed to become famous in Italy. Throughout her main career, she was known as Maria Meneghini Callas.

After La Gioconda, Maria didn't have other offers. When Serafin called her, looking for someone to sing Isolde, she told him she already knew the music, even though she had only looked at the first act. She then read the second act perfectly for Serafin. Impressed, he immediately cast her in the role. Serafin became Maria's mentor and supporter.

Maria later said that working with Serafin was the "really lucky" chance of her career. He taught her the "depth of music" and that every part of a song must have a reason and feeling behind it.

A Turning Point: I puritani and Bel Canto

A major turning point in Maria's career happened in Venice in 1949. She was scheduled to sing Brünnhilde in Die Walküre at the Teatro la Fenice. However, another singer, Margherita Carosio, who was supposed to sing Elvira in I puritani at the same theater, became ill. Since they couldn't find a replacement, Serafin told Maria she would sing Elvira in six days. Maria protested that she didn't know the role and still had three more Brünnhilde performances. Serafin simply told her, "I guarantee that you can." It was incredible for one singer to perform roles as different as Wagner's Brünnhilde and Bellini's Elvira in the same season.

Before the performance, one critic joked about a dramatic soprano singing I puritani. But after Maria's performance, a critic wrote, "Even the most skeptical had to acknowledge the miracle that Maria Callas accomplished... the flexibility of her clear, beautifully balanced voice, and her splendid high notes." Director Franco Zeffirelli said what she did in Venice was "really incredible."

This first step into the bel canto style of opera changed Maria's career. It led her to sing in operas like Lucia di Lammermoor, La traviata, La sonnambula, and Medea. Her performances helped bring back interest in these older operas by composers like Cherubini, Bellini, Donizetti, and Rossini.

Maria often learned and performed difficult roles with very little notice. She also showed her vocal skill in concerts, singing both powerful dramatic songs and light, fast coloratura pieces. For example, in a 1952 concert, she sang a dramatic scene from Macbeth, followed by the "Mad Scene" from Lucia di Lammermoor, and then finished with the "Bell Song" from Lakmé, hitting a very high E note.

Important Opera Debuts Around the World

By 1951, Maria Callas had sung in all the major opera houses in Italy, but she had not yet officially performed at Italy's most famous opera house, Teatro alla Scala in Milan. According to composer Gian Carlo Menotti, Maria had filled in for Renata Tebaldi in the role of Aida in 1950. However, La Scala's general manager, Antonio Ghiringhelli, did not like Maria at first.

Menotti recalled that Ghiringhelli had promised him any singer he wanted for a new opera, but when Menotti suggested Maria, Ghiringhelli said he would only have her as a guest. As Maria's fame grew, especially after her success in I vespri siciliani in Florence, Ghiringhelli had to change his mind. Maria made her official debut at La Scala in Verdi's I vespri siciliani on opening night in December 1951. La Scala then became her artistic home throughout the 1950s. Many new productions were created especially for Maria by famous directors like Herbert von Karajan and Luchino Visconti. Visconti later said he started directing opera only because of Maria.

The night she married Meneghini in Verona, Maria sailed to Argentina to sing at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires. She made her South American debut there on May 20, 1949, singing in Aida, Turandot, and Norma. These were her only performances on that famous stage. Her debut in the United States was five years later in Chicago in 1954, where she helped establish the Lyric Opera of Chicago with her performance of Norma.

Her debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, opening its seventy-second season on October 29, 1956, was also with Norma. This was preceded by a magazine story that focused on common ideas about Maria, including her strong personality and her difficult relationship with her mother. On November 21, 1957, Maria gave a concert to open the Dallas Civic Opera, helping to establish that company. In 1958, she gave a powerful performance as Violetta in La traviata and also sang in Medea in her only American performances of that role.

In 1958, a disagreement with Rudolf Bing, the Met's general manager, led to Maria's contract being canceled. She later performed in Il pirata with the American Opera Society in January 1959, a performance that became legendary. Bing and Maria later resolved their differences, and she returned to the Met in 1965 to sing Tosca for her final performances there.

In 1952, she made her London debut at the Royal Opera House in Norma. Maria and the London audience had what she called "a love affair." She returned to the Royal Opera House many times. It was there, on July 5, 1965, that Maria ended her stage career in the role of Tosca, in a production designed for her by Franco Zeffirelli.

Maria Callas's Weight Loss

In the early part of her career, Maria Callas was a heavy woman. She described herself as tall, about 5 feet 8.5 inches, and weighing around 200 pounds. During a break while recording an opera, her conductor, Serafin, commented that she was eating too much. Maria realized she needed to change her appearance to better fit the dramatic roles she was singing.

Between 1953 and early 1954, she lost almost 80 pounds. She transformed into what one person called "possibly the most beautiful lady on the stage." Sir Rudolf Bing, who remembered Maria as "monstrously fat" in 1951, said that after her weight loss, she was an "astonishing, slender, striking woman" who looked as if she had always been that way. Many rumors spread about how she lost weight, but Maria stated she did it by eating a healthy low-calorie diet of mostly salads and chicken. She kept her slim figure for the rest of her life.

Some people believe that losing so much weight made it harder for her to support her voice, which might have led to vocal strain later on. Others thought the weight loss made her voice softer and more feminine, and also gave her more confidence as a person and performer.

Her Unique Voice

Maria Callas's voice was, and still is, a topic of discussion. It amazed and inspired many, while others found it challenging. Walter Legge, a record producer, said that Maria had the most important quality for a great singer: a voice that you could recognize instantly.

Some critics described her voice as "ugly" or "dry" when just considering the sound itself. However, they also said that this voice could take on so many different and special colors and sounds that it became unforgettable. One conductor, Serafin, used to call her Una grande vociaccia, which means "a great ugly voice" – showing both its power and its unusual quality.

How Her Voice Was Classified

It's been hard to place Maria Callas's voice into a modern singing category. This is because, at her peak, she sang both the heaviest dramatic soprano roles and the highest, lightest, and most agile coloratura soprano roles. Serafin said, "This woman can sing anything written for the female voice."

Some experts believe Maria's voice was naturally a high soprano. Others argue that she was a "soprano sfogato" or "unlimited soprano," like singers from the 19th century. They suggest she was a natural mezzo-soprano (a middle female voice) whose range was extended through training. This meant her voice might not have been perfectly smooth and even throughout, but she used these qualities for dramatic effect. Maria herself seemed to agree, describing her early voice as "dark, almost black" and saying, "They say I was not a true soprano, I was rather toward a mezzo."

The Power and Range of Her Voice

Maria Callas's voice was described as "penetrating." Its overall volume was average, but its sharp, clear quality meant it could be heard clearly anywhere in an opera house. One critic called her vocal power "scarcely believable." Before she lost weight, her voice was "colossal," pouring out like a flood. After her weight loss, some described it as a "huge soprano leggiero," meaning a large voice that was also light and agile.

Maria's vocal range was almost three octaves. She could sing from a low F-sharp to a very high E-natural. There has been some debate about whether she ever sang a high F-natural in performances, but no clear recording exists.

Different Parts of Her Voice

Maria's voice was known for having three distinct parts:

- Low (Chest) Voice: This part was very dark and powerful. She used it for dramatic effect, often singing lower notes in this register than most sopranos.

- Middle Voice: This part had a unique and personal sound, described as "part oboe, part clarinet." It was sometimes called "veiled" or "bottled," as if she were singing into a jug.

- Upper Voice: This part was full and bright, with an impressive ability to reach very high notes. Unlike typical light coloratura singers, she would sing these high notes with more power. She could perform very fast and difficult musical passages with ease. She was also able to make a note softer while holding it, even on very high notes, which was a rare and amazing skill.

When Maria sang softly, her voice became very sweet, as if it came from "on high." This combination of power, range, and agility amazed her fellow singers. One chorus member recalled her sounding like a deep contralto at the beginning of an opera, but then hitting a high E-flat by the end. Another singer said that Maria's ability to sing coloratura (fast, decorative notes) with such a big voice was "something really special."

However, Maria's vocal parts were not always smoothly connected. She was very skilled at hiding these "gear changes" in her voice. Some believed these uneven spots were natural to her voice, while others thought they were due to technical issues. But many agreed that her technique for moving between registers was perfect, and that any "faults" were in the voice itself, not in her singing. As one singer said, "Nothing disturbed me, nothing! I bought everything that she offered me. Why? Because all of her voices, her registers, she used how they should be used—just to tell us something!"

Maria Callas as an Artist

A Musician First and Foremost

Even though many people saw Maria Callas mainly as an actress, she considered herself first and foremost a musician. She believed her voice was the "first instrument of the orchestra." Another singer, Grace Bumbry, said that when Maria sang, she followed every musical direction perfectly, yet her performance was still beautiful and moving. Conductor Victor de Sabata said that if people understood how deeply musical Maria was, they would be amazed.

Maria had a natural understanding of musical structure and a remarkable sense of timing. She could perform all kinds of musical decorations like trills and scales. Her technique allowed her to use a wide range of vocal colors and dynamics (louds and softs) exactly as she wanted. She wasn't limited by her abilities; she used them to express herself.

Maria also had a special gift for language in music. In spoken parts of operas, she always knew which word to emphasize. Her perfect smooth singing allowed her to suggest the punctuation of the text through music. She could perform the most difficult, decorative music easily, but she also used every musical ornament to express feeling, not just for show. Singer Martina Arroyo said, "What interested me most was how she gave the runs and the cadenzas words. That always floored me. I always felt I heard her saying something—it was never just singing notes. That alone is an art."

Maria Callas as an Actress

Maria Callas was also an incredible actress. One critic said that watching her last performances of Tosca felt like watching the real story the opera was based on. However, Maria was not a realistic actress. Her physical acting supported her main goal: to develop the characters' feelings through her singing. Her suffering, joy, sadness, and excitement were all expressed through her voice, carrying the words on the notes. Another soprano, Augusta Oltrabella, said that Maria was an actress in how she expressed the music, not the other way around.

Singer Ewa Podleś agreed, saying, "It's enough to hear her... Because she could say everything only with her voice!" Opera director Sandro Sequi said Maria was "extremely stylized and classic, yet at the same time, human." He felt that realism was not her style, and that's why she was the greatest opera singer, because opera itself is not realistic. Her strong facial features worked well for the grand style of early 19th-century opera.

Regarding her physical acting, conductor Nicola Rescigno said, "Maria had a way of even transforming her body for the needs of a role." For example, in La traviata, her body language showed sickness and softness. In Medea, her movements were sharp and angular, like a tiger. Sandro Sequi remembered that she was never in a hurry; her movements were slow, balanced, and precise. She could stand still for 10 minutes without moving, making everyone focus on her. Sir Rudolf Bing recalled that in one opera, Maria's quiet listening had more dramatic impact than another singer's actual singing.

The Complete Artist

Maria Callas's most special quality was her ability to bring her characters to life. She had a unique gift for translating the smallest details of a character's life into the sound of her voice.

One writer, Ethan Mordden, noted that even though her voice had flaws, Maria aimed to capture all of humanity in her singing. He felt that her vocal flaws actually added to the emotion of her performances. Conductor Carlo Maria Giulini believed that Maria perfectly combined words, music, and action in her art. He recalled that during her performances of La traviata, "reality was onstage." Everything else seemed fake compared to the truth and life happening on stage. Sir Rudolf Bing shared similar feelings, saying that Maria Callas was "the most exciting artist I ever heard."

Callas and Tebaldi: A Friendly Rivalry?

In the early 1950s, people often talked about a rivalry between Maria Callas and another Italian soprano, Renata Tebaldi. Their different singing styles—Maria's often unique voice versus Tebaldi's beautiful, classical sound—brought up an old debate in opera: is beauty of sound more important, or is how expressively the sound is used?

In 1951, both singers were booked for a concert in Brazil. They had agreed not to perform extra songs (encores), but Tebaldi sang two. Maria was reportedly very upset by this. This incident started the rivalry, which became very intense in the mid-1950s. Fans of each singer would sometimes make negative comments about the other.

Tebaldi was quoted as saying, "I have one thing that Callas doesn't have: a heart." Maria was quoted in Time magazine saying that comparing her with Tebaldi was like "comparing Champagne with Cognac...No...with Coca Cola." However, people who were there said Maria only said "champagne with cognac," and someone else added the "Coca-Cola" part.

However, many experts believe these two singers should not have been compared. Tebaldi was trained in a different style of Italian singing than Maria. Maria was a dramatic soprano, while Tebaldi considered herself a lyric soprano. They generally sang different types of operas. Maria focused on powerful dramatic roles and later on bel canto operas, while Tebaldi focused on later Verdi operas and a style called verismo. They did share a few roles, like Tosca and La Gioconda.

Despite the supposed rivalry, both singers made positive comments about each other. Maria once said, "I admire Tebaldi's tone; it's beautiful—also some beautiful phrasing. Sometimes, I actually wish I had her voice." A Met official once recommended a recording of La Gioconda to Tebaldi, avoiding Maria's version due to the rivalry. But Tebaldi later found Maria's recording and asked him, "Why didn't you tell me Maria's was the best?"

Maria Callas visited Tebaldi after a performance in 1968, and the two were reunited.

Changes in Maria Callas's Voice

Some singers believe that the very demanding roles Maria Callas sang early in her career might have harmed her voice. Her close friend and fellow singer, Giulietta Simionato, felt that these early heavy roles led to a weakness in her diaphragm (the muscle used for breathing while singing), which then made it harder to control her high notes.

Other singers suggested that Maria's frequent use of her lower "chest voice" might have caused her high notes to become unsteady. Maria's husband, Meneghini, wrote that Maria experienced menopause unusually early, which could also affect a singer's voice.

Music expert Michael Scott suggested that Maria's rapid weight loss directly caused her to lose strength and breath support. Photos and videos of Maria before her weight loss show her standing very upright with relaxed shoulders. Later videos show her chest sinking, which some see as a sign of losing breath support.

However, recordings from 1940s to 1953, when she sang the heaviest roles, do not show a decline in her voice. Critics at the time praised her voice for being clear and strong. But in recordings from 1954 (right after her weight loss) and later, her voice sometimes lost its warmth and became thinner. It was around this time that unsteady high notes started to appear. Walter Legge, who produced many of her recordings, said that Maria "ran into a patch of vocal difficulties as early as 1954."

Despite this, some people felt her voice benefited from the weight loss. Critics in Chicago and London in 1954 and 1957 said her voice was more beautiful in color and more precise. Many of her most praised performances are from 1954–1958.

A recording of Maria rehearsing shortly before her death showed her voice was in much better condition than some of her later concert recordings. Maria herself believed her vocal problems were due to a loss of confidence, which she linked to a loss of breath support.

The exact reason for Maria Callas's vocal changes is still debated. It could have been health issues, early menopause, overusing her voice, loss of breath support, or loss of confidence. Whatever the cause, her main singing career was largely over by age 40.

New Research on Vocal Decline

A 2010 study by Italian vocal researchers Franco Fussi and Nico Paolillo suggested that Maria Callas was very ill when she died, and her illness was connected to her voice changing. They believe she had dermatomyositis, a rare disease that affects muscles and ligaments, including those in the voice box (larynx). They think she showed signs of this disease as early as the 1960s. The treatment for this disease can also affect heart function.

Using modern audio technology, they analyzed Maria's recordings from the 1950s to the 1970s. They found that she was losing the top part of her vocal range. Videos showed her posture seemed strained and weak. They also felt that her big weight loss in 1954 further reduced her physical support for her voice.

The researchers also looked at old footage of a famous incident in 1958 when Maria stopped a performance of Norma in Rome. This led to her being criticized as a difficult superstar. By analyzing the footage, the researchers saw that her voice was tired and she lacked control. They concluded that she really did have bronchitis and tracheitis (throat inflammation) as she claimed, and the dermatomyositis was already causing her muscles to weaken.

Later Years and Passing Away

In 1957, while still married to Giovanni Battista Meneghini, Maria Callas met Greek shipping businessman Aristotle Onassis at a party. Their close relationship received a lot of attention in the news. In November 1959, Maria left her husband. According to one of her biographers, Maria and Onassis had a son who sadly died hours after he was born on March 30, 1960.

In 1966, Maria gave up her U.S. citizenship in Paris to help end her marriage to Meneghini. Her relationship with Onassis ended two years later in 1968, when he became involved with Jacqueline Kennedy. However, Onassis's private secretary wrote in her memoir that Aristotle often met with Maria in Paris even while he was with Jackie.

Maria Callas spent her last years mostly living quietly in Paris. She passed away from a heart attack at age 53 on September 16, 1977.

A funeral service was held for her in Paris. She was later cremated, and her ashes were placed in a special wall at the Père Lachaise Cemetery. After being stolen and then found, her ashes were scattered over the Aegean Sea off the coast of Greece in the spring of 1979, as she had wished.

Maria Callas's Estate

According to some biographers, a Greek pianist named Vasso Devetzi became very close to Maria in her last years and acted almost as her agent. Maria's sister, Iakintha (Jackie) Callas, wrote in her 1990 book Sisters that Devetzi tricked Maria out of control of half of her money. Devetzi had promised to create the Maria Callas Foundation to give scholarships to young singers. After a lot of money reportedly disappeared, Devetzi eventually did establish the foundation.

Operas Maria Callas Performed

Maria Callas performed in many operas. Here are some of the roles she sang:

| Date (debut) | Composer | Opera | Role(s) | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942-04-22 | Eugen d'Albert | Tiefland (in Greek) | Marta | Olympia Theatre, Athens |

| 1944-08-14 | Ludwig van Beethoven | Fidelio (in Greek) | Leonore | Odeon of Herodes Atticus, Athens |

| 1948-11-30 | Vincenzo Bellini | Norma | Norma | Teatro Comunale Florence |

| 1958-05-19 | Vincenzo Bellini | Il pirata | Imogene | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1949-01-19 | Vincenzo Bellini | I puritani | Elvira | La Fenice, Venice |

| 1955-03-05 | Vincenzo Bellini | La sonnambula | Amina | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1964-07-05 | Georges Bizet | Carmen | Carmen | Salle Wagram, Paris |

| 1954-07-15 | Arrigo Boito | Mefistofele | Margherita | Verona Arena |

| 1953-05-07 | Luigi Cherubini | Medea | Medea | Teatro Comunale Florence |

| 1957-04-14 | Gaetano Donizetti | Anna Bolena | Anna Bolena | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1952-06-10 | Gaetano Donizetti | Lucia di Lammermoor | Lucia di Lammermoor | Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City |

| 1960-12-07 | Gaetano Donizetti | Poliuto | Paolina | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1955-01-08 | Umberto Giordano | Andrea Chénier | Maddalena di Coigny | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1956-05-21 | Umberto Giordano | Fedora | Fedora | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1954-04-04 | Christoph Willibald Gluck | Alceste | Alceste | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1957-06-01 | Christoph Willibald Gluck | Iphigénie en Tauride | Iphigénie | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1951-06-09 | Joseph Haydn | Orfeo ed Euridice | Euridice | Teatro della Pergola, Florence |

| 1943-02-19 | Manolis Kalomiris | O Protomastoras | Singer in the intermezzo | Odeon of Herodes Atticus, Athens |

| 1944-07-30 | Manolis Kalomiris | O Protomastoras | Smarágda | Odeon of Herodes Atticus, Athens |

| 1954-06-12 | Ruggero Leoncavallo | Pagliacci | Nedda | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1939-04-02 | Pietro Mascagni | Cavalleria rusticana | Santuzza | Olympia Theatre, Athens |

| 1945-09-05 | Carl Millöcker | Der Bettelstudent (in Greek) | Laura | Alexandras Avenue Theater, Athens |

| 1952-04-02 | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | Die Entführung aus dem Serail (in Italian) | Konstanze | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1947-08-02 | Amilcare Ponchielli | La Gioconda | La Gioconda | Verona Arena |

| 1955-11-11 | Giacomo Puccini | Madama Butterfly | Cio-cio-san | Civic Opera House, Chicago |

| 1957-07-18 | Giacomo Puccini | Manon Lescaut | Manon Lescaut | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1940-06-16 | Giacomo Puccini | Suor Angelica | Suor Angelica | Athens Conservatoire |

| 1948-01-29 | Giacomo Puccini | Turandot | Turandot | La Fenice, Venice |

| 1956-08-20 | Giacomo Puccini | La bohème | Mimi | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1942-08-27 | Giacomo Puccini | Tosca | Tosca | Olympia Theatre, Athens |

| 1952-04-26 | Gioachino Rossini | Armida | Armida | Teatro Comunale Florence |

| 1956-02-16 | Gioachino Rossini | Il barbiere di Siviglia | Rosina | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1950-10-19 | Gioachino Rossini | Il turco in Italia | Donna Fiorilla | Teatro Eliseo, Rome |

| 1954-12-07 | Gaspare Spontini | La vestale | Giulia | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1937-01-28 | Arthur Sullivan | H.M.S. Pinafore | Ralph Rackstraw | New York P.S. 164 |

| 1936 | Arthur Sullivan | The Mikado | Unknown | New York P.S. 164 |

| 1941-02-15 | Franz von Suppé | Boccaccio (in Greek) | Beatrice | Olympia Theatre, Athens |

| 1948-09-18 | Giuseppe Verdi | Aida | Aida | Teatro Regio (Turin) |

| 1954-04-12 | Giuseppe Verdi | Don Carlo | Elisabetta di Valois | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1948-04-17 | Giuseppe Verdi | La forza del destino | Leonora di Vargas | Politeama Rossetti, Trieste |

| 1952-12-07 | Giuseppe Verdi | Macbeth | Lady Macbeth | Teatro alla Scala, Milan |

| 1949-12-20 | Giuseppe Verdi | Nabucco | Abigaile | Teatro San Carlo, Naples |

| 1952-06-17 | Giuseppe Verdi | Rigoletto | Gilda | Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City |

| 1951-01-14 | Giuseppe Verdi | La traviata | Violetta Valéry | Teatro Comunale Florence |

| 1950-06-20 | Giuseppe Verdi | Il trovatore | Leonora | Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City |

| 1951-05-26 | Giuseppe Verdi | I vespri siciliani | La duchessa Elena | Teatro Comunale Florence |

| 1949-02-26 | Richard Wagner | Parsifal (in Italian) | Kundry | Teatro dell'Opera, Rome |

| 1947-12-30 | Richard Wagner | Tristan und Isolde (in Italian) | Isolde | La Fenice, Venice |

| 1949-01-08 | Richard Wagner | Die Walküre (in Italian) | Brünnhilde | La Fenice, Venice |

Notable Recordings of Maria Callas

Maria Callas made many important recordings throughout her career. Most of these are in mono (single channel sound) unless noted. Live performances are often available from different record labels. In 2014, Warner Classics released a special "Maria Callas Remastered Edition" of all her studio recordings, improved with modern sound technology.

Here are some of her most famous recordings:

- Verdi, Nabucco, live performance, Napoli, December 20, 1949

- Verdi, Il trovatore, live performance, Mexico City, June 20, 1950. In this recording, Callas sings a very high D flat note.

- Wagner, Parsifal, live performance, RAI Rome, November 20/21, 1950 (in Italian)

- Verdi, Il trovatore, live performance, Teatro San Carlo, Naples, January 27, 1951

- Verdi, Les vêpres siciliennes, live performance, Teatro Comunale Florence, May 26, 1951 (in Italian)

- Verdi, Aida, live performance, Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, July 3, 1951

- Rossini, Armida, live performance, Teatro Comunale Florence, April 26, 1952

- Ponchielli, La Gioconda, studio recording for Cetra Records, September 1952

- Bellini, Norma, live performance, Covent Garden, London, November 18, 1952

- Verdi, Macbeth, live performance, La Scala, Milan, December 7, 1952

- Donizetti, Lucia di Lammermoor, studio recording for EMI, January–February 1953

- Verdi, Il trovatore, live performance, La Scala February 23, 1953

- Bellini, I puritani, studio recording for EMI, March–April 1953

- Cherubini, Médée, live performance, Teatro Comunale, Florence, May 7, 1953 (in Italian)

- Mascagni, Cavalleria rusticana, studio recording for EMI, August 1953

- Puccini, Tosca (1953 EMI recording), studio recording for EMI, August 1953.

- Verdi, La traviata, studio recording for Cetra Records, September 1953

- Cherubini, Médée, live performance, La Scala, Milan, December 10, 1953 (in Italian)

- Bellini, Norma, studio recording for EMI, April–May 1954

- Gluck, Alceste, La Scala, Milan, April 4, 1954 (in Italian)

- Leoncavallo, Pagliacci, studio recording for EMI, June 1954

- Verdi, La forza del destino, studio recording for EMI, August 1954

- Rossini, Il turco in Italia, studio recording for EMI, August–September 1954

- Puccini Arias (songs from Manon Lescaut, La bohème, Madama Butterfly, Suor Angelica, Gianni Schicchi, Turandot), studio recording for EMI, September 1954

- Lyric & Coloratura Arias (songs from Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia, Verdi's I vespri siciliani, Meyerbeer's Dinorah, Boito's Mefistofele, Delibes's Lakmé, Catalani's La Wally, Giordano's Andrea Chénier, Cilea's Adriana Lecouvreur), studio recording for EMI, September 1954

- Spontini, La vestale, live performance, La Scala, Milan, December 7, 1954 (in Italian)

- Verdi, La traviata, live performance, La Scala, Milan, May 28, 1955

- Callas at La Scala (songs from Cherubini's Médée, Spontini's La vestale, Bellini's La sonnambula), studio recording for EMI, June 1955

- Puccini, Madama Butterfly, studio recording for EMI, August 1955

- Verdi, Aida, studio recording for EMI, August 1955

- Verdi, Rigoletto, studio recording for EMI, September 1955

- Donizetti, Lucia di Lammermoor, live performance, Berlin, September 29, 1955

- Bellini, Norma, live performance, La Scala, Milan, December 7, 1955

- Verdi, Il trovatore, studio recording for EMI, August 1956

- Puccini, La bohème, studio recording for EMI, August–September 1956. This was her only recording of the complete opera.

- Verdi, Un ballo in maschera, studio recording for EMI, September 1956

- Rossini, Il barbiere di Siviglia, studio recording for EMI in stereo, February 1957

- Bellini, La sonnambula, studio recording for EMI, March 1957

- Donizetti, Anna Bolena, live performance, La Scala, Milan, April 14, 1957

- Gluck, Iphigénie en Tauride, La Scala Milan, June 1, 1957 (in Italian)

- Bellini, La sonnambula, live performance, Cologne, July 4, 1957

- Puccini, Turandot, studio recording for EMI, July 1957

- Puccini, Manon Lescaut, studio recording for EMI, July 1957.

- Cherubini, Médée, studio recording for Ricordi in stereo, September 1957 (in Italian)

- Verdi, Un ballo in maschera, live performance, La Scala, Milan, December 7, 1957

- Verdi, La traviata, live performance, Lisbon, March 27, 1958

- Verdi, La traviata, live performance, London, June 20, 1958; many critics consider this her best recording of this opera.

- Verdi Heroines (songs from Nabucco, Ernani, Macbeth, Don Carlo), studio recording for EMI in stereo, September 1958

- Mad Scenes (songs from Anna Bolena, Bellini's Il pirata and Ambroise Thomas's Hamlet), studio recording for EMI in stereo, September 1958

- Cherubini, Médée live performance at the Dallas Civic Opera November 6, 1958; considered her most notable performance of this opera. (in Italian)

- Donizetti, Lucia di Lammermoor, studio recording for EMI in stereo, March 1959

- Ponchielli, La Gioconda, studio recording for EMI in stereo, September 1959

- Bellini, Norma, studio recording for EMI in stereo, September 1960

- Callas à Paris (songs from Gluck's Orphée et Eurydice, Alceste, Thomas's Mignon, Gounod's Roméo et Juliette, Bizet's Carmen, Saint-Saëns's Samson and Delilah, Massenet's Le Cid, Charpentier's Louise), studio recording for EMI in stereo, March–April 1961

- Callas à Paris II (songs from Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride, Berlioz's La damnation de Faust, Gounod's Faust, Bizet's Les pêcheurs de perles, Massenet's Manon, Werther), studio recording for EMI in stereo, May 1963

- Mozart, Beethoven, and Weber (songs from Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, Weber's Oberon), studio recording for EMI in stereo, December 1963 – January 1964

- Rossini and Donizetti Arias (songs from Rossini's La Cenerentola, Semiramide, Guglielmo Tell, Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore, Lucrezia Borgia, La figlia del reggimento), studio recording for EMI in stereo, December 1963 – April 1964

- Verdi Arias (songs from Aroldo, Don Carlo, Otello), studio recording for EMI in stereo, December 1963 – April 1964

- Puccini, Tosca, live performance, London, January 24, 1964

- Bizet, Carmen, studio recording for EMI in stereo, July 1964. This was her only recording of the complete opera.

- Puccini, Tosca, studio recording for EMI in stereo, December 1964.

- Verdi Arias II (songs from I Lombardi, Attila, Il corsaro, Il trovatore, I vespri siciliani, Un ballo in maschera, Aida), studio recording for EMI in stereo, January 1964 – March 1969

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Maria Callas para niños

In Spanish: Maria Callas para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |