History of Alsace facts for kids

The history of Alsace has been shaped by the Rhine River, its smaller rivers, good weather, rich soil, and easy access through the Vosges Mountains. People first lived here during the Stone Age. Later, groups speaking Celtic and Germanic languages settled in the area. The Roman army led by Julius Caesar then conquered it.

After the Roman Empire fell, the area got its name and became known as an early medieval region. Since then, different European powers have controlled Alsace. These include the Kingdom of Alamannia, the Frankish Empire, Lotharingia, the Holy Roman Empire, France, and the German Empire. Alsace has been part of France since the end of World War II.

Contents

- Early Humans in Alsace

- First Farmers in Alsace

- Bronze Age in Alsace

- Iron Age in Alsace

- Roman Alsace

- Alemannic and Frankish Alsace

- Alsace in the Holy Roman Empire

- Alsace Becomes Part of France

- From French Revolution to Franco-Prussian War

- Struggle Between France and Germany

- After World War II

- Timeline

- Images for kids

Early Humans in Alsace

The oldest signs of human-like creatures in Alsace are from about 700,000 years ago. Neanderthals lived in the region by 250,000 years ago. Important Neanderthal sites are found near Mutzig and in the Bruche valley.

Around 35,000 years ago, early modern humans arrived. Their remains have been found at Achenheim and Entzheim.

The Mannlefelsen cave near Oberlarg shows many signs of people living there. This was from about 13,000 years ago (late Stone Age) to 5,500 years ago (end of the Middle Stone Age). Tools like stone scrapers and arrowheads were found. Animal bones like red deer and wild boar show what they hunted.

First Farmers in Alsace

By 5300 BCE, Neolithic farming groups settled in Alsace. They liked the light, fertile soil between the Ill River and the Vosges Mountains. In Alsace, people grew einkorn and emmer wheat, barley, and vetch. They also raised cows, pigs, and sheep. This was typical for farming in Europe at that time. They used polished stone tools to clear forests and farm. They also made pottery and leather goods.

Archaeologists divide the Neolithic period in Alsace into four main parts. The first is the Linear Pottery Culture (LBK) from 5300 BCE to 4900 BCE. This was followed by the middle Neolithic, recent Neolithic, and a final, less known period.

LBK culture is known for pottery with special linear designs and large timber longhouses. LBK ideas spread to Alsace from the Danube and Hungarian plains. Later, around 4200 BCE, a new culture called Michelsberg culture appeared in northern Alsace. People from the Parisian basin moved east into Alsace. Skeletons found near Gougenheim suggest these new people mixed with earlier hunter-gatherers. At Bergheim, a mass grave shows these western invaders were violently killed. But eventually, the Michelsberg people settled in much of Alsace.

Bronze Age in Alsace

The Bronze Age in Alsace (2200 BCE - 800 BCE) brought new things. People started using bronze widely. They also built special burial mounds called tumuli and forts on hilltops.

At the very start of the Bronze Age, around 2200 BCE, the Bell Beaker culture was present. This culture came from western Europe. In Alsace, their sites have been found near Achenheim and Kunheim. They left behind bell-shaped pottery and buried their dead underground without mounds.

After 2200 BCE, burial mounds became more common. These are linked to the Tumulus culture of the Middle Bronze Age in central Europe. Some experts believe these cultures, like the Corded Ware culture and Yamnaya Culture, brought Indo-European languages to Europe. These languages later led to Celtic languages spoken in Gaul. In Alsace, you can find important tumulus graves from this time in the forest of Haguenau.

After a short cool period, the number of settlements grew a lot. This time belongs to the Urnfield culture. They cremated their dead and buried the ashes in pots in fields. Archaeologists think that during this time, smaller settlements were controlled by larger ones. Big Bronze Age settlements have been found near Reichstett and Colmar.

Iron Age in Alsace

The Iron Age in Alsace (800 BCE - 52 BCE) began with iron tools and ended when Rome took over Gaul. In Alsace, like much of central Europe, there were two main phases: the Hallstatt culture (800 BCE - 480 BCE) and La Tène (480 BCE - 52 BCE).

The Hallstatt period saw a big difference in wealth and power among people. Trade with Mediterranean regions grew, leading to a rich group of leaders, or "Hallstatt aristocracy." They showed off their wealth with decorated weapons and fine goods.

In Alsace, the hill fort Britzgyberg, near Illfurth, was a very important center for these rich people. Greek pottery and other luxury items were found there. There are also several rich Hallstatt tombs in Alsace. These tombs contain jewelry, decorated swords, and horse gear. Some very rich tombs even have a full funeral cart, like at Hatten and Ensisheim. A young woman buried near Nordhouse had a lot of fancy gold jewelry.

Away from these rich centers, there were small farming communities. They lived in different environments, even wetlands, showing that farming had spread widely.

Later, in the second and first centuries BCE, large fortified settlements appeared. These are called oppida. They were bigger than Hallstatt hill forts and had strong defensive walls. The largest oppidum in Alsace was the Oppidum du Fossé des Pandours, northwest of modern Strasbourg.

Roman Alsace

Around 100 BCE, Germanic tribes started settling along the Rhine and Danube rivers. These areas had long been home to Celtic-speaking Gauls. By the first century BCE, the Triboci, a Germanic tribe, occupied much of Alsace.

Rome conquered Alsace early in the Gallic Wars. In 58 BCE, the Aedui, a Gallic tribe, asked Rome for help against the Suebi. The Suebi were a Germanic tribe led by Ariovistus. They had taken control of parts of Gaul. Julius Caesar tried to negotiate, but Ariovistus refused. A battle happened near Cernay in southern Alsace. Caesar defeated the Suebi, and Ariovistus fled. This brought a long period of peace for the Gauls along the Rhine.

From the first to the early fifth century CE, Alsace was part of the Roman province of Germania Superior. This province was officially set up in 85 CE. The Rhine River, which forms Alsace's eastern border, was also the Roman frontier, or limes. This was true from 53 BCE to about 70 CE, and again from 250 CE until the fall of the Empire. Throughout the Roman period, Argentoratum (Strasbourg) was a major Roman military camp. Roman forts were also near Biesheim on the Rhine.

Alsace was managed from three main cities. These were Brocomagus (Brumath in Alsace), Divodorum (Metz in Lorraine), and Augusta Raurica (near Basel in Switzerland). Argentoratum later took over Brocumagus's role. Cities grew and the population increased during Roman times. This growth likely peaked in the second century. Many city buildings were made of wood, unlike the stone buildings in the rest of Gaul. This was because there wasn't much accessible stone in the Rhine valley. In the fourth and fifth centuries, some cities were fortified with walls. These included Brocumagus, Tres Tabernae Cesaris (Saverne), and Argentovaria (Horbourg). City life quickly declined in Alsace in the fifth century.

People mainly grew cereals for food. Most historians believe the Romans brought wine growing to the area, though there isn't much direct evidence from that time. Large amounts of wine, oil, and salted meats were imported from other parts of the Roman Empire. Manufacturing centers also developed, including a steel works near the military camps at Argentoratum.

Alemannic and Frankish Alsace

The Alemanni People

The Alamanni first appeared in history in the third century CE. They were a group of Germanic peoples from what is now southwestern Germany. For a long time, they were a big threat to the Roman Empire from across the upper Rhine.

In 355 CE, the Alamanni attacked Argentoratum. In 357 CE, the emperor Julian took Argentoratum back. But by 406 CE, when Germanic tribes famously crossed the Rhine, Rome could no longer control its border there.

The language of the Alamanni is thought to be the basis for modern German dialects spoken in the Upper Rhine area. These include Alsatian, Swabian, and Swiss German. The Alamanni remained pagan until the fifth century.

The Franks, who lived north of the Alamanni, were their main rivals for a long time. In 496 CE, Clovis of the Franks defeated the Alamanni at the Battle of Tolbiac. Alsace then became part of the Frankish Kingdom of Austrasia. It remained part of the Frankish Empire until it broke apart after the death of Louis the Pious.

Alsace Under Frankish Kings

Under Clovis's successors, the people of Alsace became Christian. Many monasteries were built during this time. These were founded by important local families and Frankish rulers. Monasteries became important centers of power and wealth for landowners. They also provided educated clergy, who were vital for running things in the post-Roman world. Frankish kings valued them for this.

Alsace After the Frankish Empire Broke Up

After Louis the Pious died in 840, the Frankish Empire was divided many times by Charlemagne's descendants. Because of these divisions, Alsace became part of Middle Francia (843), then the Kingdom of Lotharingia (855), and finally East Francia (870).

Alsace in the Holy Roman Empire

Around this time, the areas around Alsace often broke into smaller parts and then rejoined larger ones. This was common in the Holy Roman Empire. Alsace became very rich in the 12th and 13th centuries under the Hohenstaufen emperors. Frederick I made Alsace a special province. It was ruled by non-noble civil servants called ministeriales. The idea was that these men would be more loyal to the emperor. The province had one main court and a central government in Hagenau.

Frederick II later asked the Bishop of Strasbourg to rule Alsace. But his power was challenged by Count Rudolf of Habsburg. Strasbourg grew to be the biggest and most important trading town in the region. In 1262, after a long fight with the bishops, its citizens became a free imperial city. Strasbourg was a stop on trade routes from Paris to Vienna and a port on the Rhine. This made it the political and economic center of the region. Other cities like Colmar and Hagenau also grew. They gained some freedom as part of the "Decapole," a group of ten free towns.

Like much of Europe, Alsace's good times ended in the 14th century. There were harsh winters, bad harvests, and the Black Death. People blamed Jews for these problems, leading to massacres in 1336 and 1339. In 1349, Jews in Alsace were accused of poisoning wells. This led to the killing of thousands of Jews during the Strasbourg pogrom. Jews were then forbidden to live in the town. Another disaster was the Rhine rift earthquake in 1356, which destroyed Basel. Alsace became rich again under Habsburg rule during the Renaissance.

The Holy Roman Empire's central power started to weaken. France, which had become a strong, unified country, began to expand eastward. In 1299, France suggested a marriage alliance where Alsace would be a dowry, but it didn't happen. In 1307, the town of Belfort was first given a charter. For the next century, France was busy with the Hundred Years' War. After the war, France again looked to expand to the Rhine. In 1444, a French army entered Lorraine and Alsace.

In 1469, Upper Alsace was sold to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. But taxes were still paid to Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor. Frederick used this to get full control of Upper Alsace back in 1477. It then became part of the Habsburg family's lands. The town of Mulhouse joined the Swiss Confederation in 1515 and stayed there until 1798.

By the time of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, Strasbourg was a wealthy city. Its people became Protestant in 1523. Martin Bucer was an important Protestant reformer there. But the Catholic Habsburgs tried to stop Protestantism in Upper Alsace. So, Alsace became a mix of Catholic and Protestant areas.

Alsace Becomes Part of France

This situation continued until 1639. Most of Alsace was then conquered by France. This was to prevent it from falling into the hands of the Spanish Habsburgs. In 1646, the Habsburgs sold their Sundgau territory (mostly in Upper Alsace) to France for a large sum of money. When the fighting ended in 1648 with the Treaty of Westphalia, most of Alsace was recognized as part of France. However, some towns remained independent.

The treaty was complex for Alsace. The French king gained control, but the existing rights and customs of the people were mostly kept. France kept its customs border along the Vosges mountains. This meant Alsace's economy was still more connected to neighboring German-speaking lands. The German language was still used in local government, schools, and at the University of Strasbourg. The 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau, which banned French Protestantism, was not applied in Alsace. France did try to promote Catholicism. For example, Strasbourg Cathedral, which had been Lutheran, was returned to the Catholic Church. But compared to the rest of France, Alsace had more religious tolerance.

Wars had reduced the population in the region. This created chances for immigrants from Switzerland, Germany, Austria, and other lands. People continued to move there until the mid-18th century.

France made its control stronger with the 1679 Treaties of Nijmegen. These treaties brought most remaining towns under French rule. France took Strasbourg in 1681 without being provoked. These changes were officially recognized in the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, which ended the War of the Grand Alliance.

From French Revolution to Franco-Prussian War

The year 1789 brought the French Revolution. Alsace was then divided into two departments: Haut-Rhin and Bas-Rhin. People from Alsace played an active part in the Revolution. On July 21, 1789, after hearing about the Storming of the Bastille in Paris, a crowd stormed the Strasbourg city hall. This forced city leaders to flee and ended the old feudal system in Alsace.

In 1792, Rouget de Lisle wrote the Revolutionary song "La Marseillaise" in Strasbourg. It was first called "Marching song for the Army of the Rhine." This song later became the national anthem of France. It was first played in April of that year for the mayor of Strasbourg, Philippe-Frédéric de Dietrich. Some famous generals of the French Revolution also came from Alsace, like Kellermann and Kléber.

At the same time, some Alsatians opposed the Jacobins. They supported bringing back the monarchy. They were sympathetic to the invading armies of Austria and Prussia. Many people from the Sundgau region went on "pilgrimages" to places like Mariastein Abbey in Switzerland for baptisms and weddings. When the French Revolutionary Army won, tens of thousands fled east. When they were later allowed to return, often not until 1799, they found their lands and homes had been taken. This led many families to move to new lands in the Russian Empire in 1803–4 and again in 1808.

After Napoleon I of France was finally defeated in 1815, Alsace was occupied by foreign armies from 1815 to 1818. This included over 280,000 soldiers in Bas-Rhin alone. This greatly harmed trade and the economy. Old land trade routes shifted to new sea routes in the Mediterranean and Atlantic.

The population grew quickly, from 800,000 in 1814 to over a million by 1846. This growth, combined with economic problems, led to hunger, housing shortages, and a lack of jobs for young people. So, many Alsatians left. They went to Paris, Russia, and the Austrian Empire. Austria offered good deals to colonists in Eastern Europe to help control new territories. Many Alsatians also sailed to the United States from 1820 to 1850. They settled in places like Illinois and Indiana. Some Alsatian immigrants became important in American economic growth. Others went to Canada, settling in southwestern Ontario.

Struggle Between France and Germany

The Franco-Prussian War began in July 1870. France was defeated in May 1871 by the Kingdom of Prussia and other German states. This war led to the unification of Germany. Otto von Bismarck added Alsace and northern Lorraine to the new German Empire in 1871. France gave up over 90% of Alsace and a quarter of Lorraine, as stated in the Treaty of Frankfurt.

Unlike other German states, the new Imperial territory of Alsace-Lorraine was directly controlled by the Kaiser in Berlin. Between 100,000 and 130,000 Alsatians (out of about 1.5 million people) chose to remain French citizens. Many of them moved to French Algeria. Alsace-Lorraine only gained some self-rule in 1911, with its own flag and anthem. However, the Saverne Affair in 1913 showed the limits of this new tolerance for Alsatian identity.

During the First World War, many Alsatians served as sailors in the German navy. They took part in naval mutinies that led to the Kaiser's abdication in November 1918. This left Alsace-Lorraine without a ruler. The sailors returned home and tried to create an independent republic. While Jacques Peirotes, the mayor of Strasbourg, declared the end of the German Empire and the start of the French Republic, a self-declared government announced the independence of the "Republic of Alsace-Lorraine."

French troops entered Alsace less than two weeks later. They stopped worker strikes and removed the new revolutionary groups from power. Many Alsatians and local German officials welcomed the return of order.

US President Woodrow Wilson had said that the region should rule itself. But France did not allow a public vote, as granted to some other German territories by the League of Nations. This was because the French saw Alsatians as French people freed from German rule. Germany gave the region to France under the Treaty of Versailles.

Policies quickly came in that banned German and required French. However, election propaganda was allowed to have German translations until 2008. To avoid upsetting Alsatians, the region was not subject to some legal changes that happened in the rest of France. For example, the 1905 French law separating Church and State was not applied in Alsace.

Alsace-Lorraine was occupied by Germany in 1940 during the Second World War. It was never officially made part of Germany, but it was joined into the Greater German Reich. Alsace was merged with Baden, and Lorraine with the Saarland. During the war, 130,000 young men from Alsace and Lorraine were forced into the German army. They were called malgré-nous (against our will). Some even volunteered for the Waffen SS. A few of these were involved in war crimes, like the Oradour-sur-Glane massacre. Most died on the eastern front. The few who could fled to Switzerland or joined the resistance. In July 1944, 1500 malgré-nous were released from Soviet capture and sent to Algiers. There, they joined the Free French Forces.

After World War II

Today, some laws in Alsace are different from the rest of France. This is known as the local law.

In recent years, the Alsatian language is being promoted again. Local, national, and European groups see it as part of the region's identity. Alsatian is taught in schools, but it's not required. German is also taught as a foreign language in local kindergartens and schools. However, the Constitution of France still says that French is the only official language of the Republic.

Timeline

| Year(s) | Event | Ruled by | Official or common language |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5400–4500 BC | Linear Pottery cultures | - | Unknown |

| 2300–750 BC | Bell Beaker cultures | — | Proto-Celtic spoken |

| 750–450 BC | Hallstatt culture (early Celts) | — | Old Celtic spoken |

| 450–58 BC | Celts/Gauls settled in Gaul, including Alsace; trade with Greece evident | Celts/Gauls | Gaulish Celtic widely spoken |

| 58 / 44 BC– AD 260 |

Alsace and Gaul conquered by Caesar, became province of Germania Superior | Roman Empire | Latin; Gallic widely spoken |

| 260–274 | Postumus creates breakaway Gallic Empire | Gallic Empire | Latin, Gallic |

| 274–286 | Rome takes back the Gallic Empire, Alsace | Roman Empire | Latin, Gallic, Germanic (only in Argentoratum) |

| 286–378 | Diocletian divides the Roman Empire | Roman Empire | |

| around 300 | Germanic groups begin moving into the Roman Empire | Roman Empire | |

| 378–395 | Visigoths rebel, leading to German and Hun invasions | Roman Empire | Alamannic Incursions |

| 395–436 | Death of Theodosius I, permanent split of Roman Empire | Western Roman Empire | |

| 436–486 | Germanic invasions of the Western Roman Empire | Roman Tributary of Gaul | Alamannic |

| 486–511 | Lower Alsace conquered by the Franks | Frankish Realm | Old Frankish, Latin; Alamannic |

| 531–614 | Upper Alsace conquered by the Franks | Frankish Realm | |

| 614–795 | All of Alsace becomes part of the Frankish Kingdom | Frankish Realm | |

| 795–814 | Charlemagne begins reign, crowned Holy Roman Emperor | Frankish Empire | Old Frankish; Frankish and Alamannic |

| 814 | Death of Charlemagne | Carolingian Empire | Old Frankish; Frankish and Alamannic varieties of Old High German |

| 847–870 | Treaty of Verdun gives Alsace and Lotharingia to Lothar I | Middle Francia (Carolingian Empire) | Frankish; Frankish and Alamannic varieties of Old High German |

| 870–889 | Treaty of Mersen gives Alsace to East Francia | East Francia (German Kingdom of the Carolingian Empire) | Frankish, Frankish and Alamannic varieties of Old High German |

| 889–962 | Carolingian Empire breaks up, Magyars and Vikings raid Alsace | Kingdom of Germany | Frankish and Alamannic varieties of Old High German |

| 962–1618 | Otto I crowned Holy Roman Emperor | Holy Roman Empire | Old High German, Middle High German, Modern High German; Alamannic and Franconian German dialects |

| 1618–1674 | Louis XIII annexes parts of Alsace during the Thirty Years' War, confirmed at the Peace of Westphalia | Holy Roman Empire | German; Alamannic and Franconian dialects (Alsatian) |

| 1674–1871 | Louis XIV annexes the rest of Alsace during the Franco-Dutch War, making it fully French | Kingdom of France | French (Alsatian and German tolerated) |

| 1871–1918 | Treaty of Frankfurt after the Franco-Prussian War gives Alsace to German Empire | German Empire | German; Alsatian, French |

| 1919–1940 | Treaty of Versailles after World War I gives Alsace to France | France | French; Alsatian, French, German |

| 1940–1944 | Nazi Germany conquers Alsace, creating Gau Baden-Elsaß | Nazi Germany | German; Alsatian, French, German |

| 1945–present | French control | France | French; French and Alsatian German (declining minority language) |

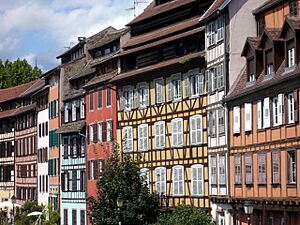

Images for kids

-

Louis XIV receiving the keys of Strasbourg in 1681