History of Christianity in the United States facts for kids

Christianity came to North America when Europeans started settling here in the 1500s and 1600s. The Spanish, French, and British brought Roman Catholicism to their colonies like New Spain, New France, and Maryland. People from Northern Europe brought Protestantism to places like Massachusetts Bay Colony, New Netherland, and Virginia colony.

Many different Protestant groups settled in the US. These included Anglicans, Methodists, Baptists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, Quakers, Mennonites, and the Moravians. They helped spread their faith in the new country. Today, most Christians in the United States are Mainline Protestants, Evangelicals, or Catholics.

Contents

Early Christianity in the Colonies

The Spanish were the first Europeans to build settlements in North America. They founded St. Augustine, Florida in 1565. This means the first Christians in the area that became the United States were Roman Catholics.

However, the Thirteen Colonies that formed the US in 1776 were mostly Protestant. Many Protestant settlers came from England. They sought religious freedom from the Church of England. Most of these settlers were Puritans. By the time of the American Revolution, the English colonies were almost entirely Protestant.

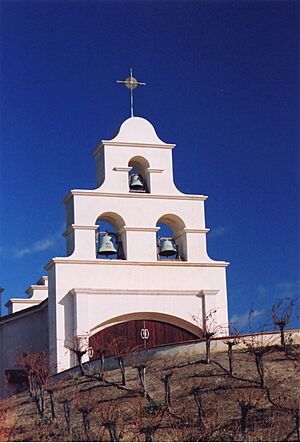

Spanish Catholic Missions

Catholicism arrived in the areas that are now the United States with Spanish conquistadors and settlers. This was just before the Protestant Reformation began in 1517. They settled in present-day Florida (1513) and the Southwest. The first Christian church service in the US was a Catholic Mass in Pensacola, Florida.

The Spanish spread Roman Catholicism through Spanish Florida using their mission system. These missions reached into Georgia and the Carolinas. Later, Spain built missions in what are now Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. Junípero Serra (who died in 1784) started many missions in California. These missions became important centers for the economy, government, and religion.

French Catholic Territories

In the French territories, Catholicism arrived with new colonies and forts. These were built in places like Detroit, St. Louis, Mobile, and New Orleans. In the late 1600s, French explorers claimed a huge area of North America. This region stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada. It was known as French Louisiana.

French Louisiana included land on both sides of the Mississippi River. It also covered lands that drained into the river. Many present-day states were once part of this vast French territory. These include Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

British Protestant Colonies

Many British colonies in North America were settled in the 1600s. People came here because they faced religious persecution in Europe. They refused to change their strong religious beliefs, which came from the Protestant Reformation (around 1517).

Virginia's Church of England

The Church of England was the official church in the Colony of Virginia starting in 1619. English authorities sent Anglican priests to the colony. Being "established" meant that local taxes supported the church. These taxes paid the minister's salary and helped with local government needs like roads and helping the poor.

The parish was an important local unit. It was led by a rector (minister) and managed by a vestry. The vestry was a committee of respected community members. Parishes often had a church farm to help support them financially. People were expected to attend church services.

Ministers often complained that colonists were not very interested during services. They said people would sleep, whisper, or look out windows. There were not enough ministers for everyone. So, ministers encouraged people to be religious at home. They used the Book of Common Prayer for private worship. This allowed devout Anglicans to have a strong religious life even outside church services. This focus on personal faith helped lead to the First Great Awakening.

New England's Puritan Settlers

A group known as the Pilgrims settled Plymouth Colony in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1620. They were looking for safety from conflicts in England.

The Puritans were a much larger group than the Pilgrims. They started the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629 with 400 settlers. Puritans were English Protestants who wanted to change the Church of England. They felt it still had too many practices from Roman Catholicism. Within two years, 2,000 more settlers arrived. From 1630, about 20,000 Puritans moved to America from England. They wanted the freedom to worship as they chose. Most settled in New England.

The Puritans created a very religious and close-knit society. They hoped their new land would be a "redeemer nation".

Religious Tolerance in Other Colonies

Roger Williams believed in religious tolerance. He also thought the church and government should be separate. He was forced to leave the Massachusetts Bay Colony. He then founded Rhode Island Colony. This colony became a safe place for other religious groups who were escaping the Puritans. Because there was no official state religion, religious practices in the colonies became very diverse.

Delaware was first settled by Lutherans from New Sweden. When the Dutch took over, the Swedes and Finns could keep their churches. Later, when the English took over from the Dutch, the Dutch, Swedes, and Finns still had religious freedom. This helped create a culture of more religious tolerance.

The Religious Society of Friends, also known as Quakers, formed in England in 1652. Quakers were treated very badly in England for their different beliefs. This led them to seek safety in New Jersey in the 1670s. In 1681, Quaker leader William Penn received a charter for the Province of Pennsylvania. Many more Quakers came to Pennsylvania and Delaware. They wanted to worship freely. By 1685, about 8,000 Quakers had arrived. Quakers believed in religious freedom for everyone.

The first Germans to settle in Pennsylvania arrived in Philadelphia in 1683. They included Mennonites and some Dutch Quakers.

Maryland's Catholic Beginnings

Catholicism came to the English colonies when the Province of Maryland was founded in 1634. Jesuits (Catholic priests) came with the first settlers from England. Maryland was one of the few English colonies in North America that had many Catholics.

However, after the Royalists lost the English Civil War in 1646, strict laws were made against Catholics. Catholic schools were closed, and Jesuits were forced to leave. During most of the colonial period in Maryland, Jesuits secretly ran Catholic schools.

Maryland was special because it allowed religious toleration when many other English colonies were very Protestant. The Maryland Toleration Act, passed in 1649, was one of the first laws to clearly state tolerance for different Christian religions. It is seen as an early step towards the First Amendment.

The English kings did not hate the Roman Catholic Church. But their subjects often did. Catholics were often bothered and treated badly in England during the 1600s. George Calvert wanted to find a safe place for his Catholic friends. So, he got a charter for Maryland from King Charles I in 1632. In 1634, two ships, the Ark and the Dove, brought about 200 settlers to Maryland.

The number of Roman Catholics in Maryland went up and down. They became a smaller part of the population. After the Glorious Revolution of 1689 in England, laws took away Catholics' rights. They could not vote, hold office, educate their children, or worship publicly. Until the American Revolution, Roman Catholics in Maryland were treated as outsiders. At the time of the Revolution, Catholics were less than 1% of the population in the thirteen colonies.

Anti-Catholic Feelings

Anti-Catholic feelings in America started during the Protestant Reformation. Protestants wanted to fix what they saw as mistakes in the Catholic Church. So, they strongly opposed the Catholic leaders and the Pope. These strong feelings came to the New World with British colonists. Most of these colonists were Protestant. They opposed not only the Catholic Church but also the Church of England. They felt the Church of England was not Protestant enough.

Many British colonists, like the Puritans, were escaping religious persecution by the Church of England. So, early American religious culture had a very strong anti-Catholic bias from these Protestant groups.

One historian wrote that a general anti-Catholic feeling was "strongly encouraged in all thirteen colonies." Colonial laws often had specific rules against Roman Catholics. He also noted that a shared dislike of the Catholic Church could bring together Anglican and Puritan ministers, even though they had other differences.

Russian Orthodox Presence

Russian traders settled in Alaska in the 1700s. In 1740, a Divine Liturgy (an Orthodox church service) was held on a Russian ship off the Alaskan coast. In 1794, the Russian Orthodox Church sent missionaries, including Herman of Alaska, to start a formal mission in Alaska. Their work helped many native Alaskans become Orthodox Christians. A diocese (a church district) was created, and Innocent of Alaska became its first bishop.

18th Century Religious Changes

By 1780, about 10% to 30% of adult colonists belonged to a church. This number did not include enslaved people or Native Americans. North Carolina had the lowest percentage, about 4%. New Hampshire and South Carolina had the highest, about 16%.

The Great Awakening

Evangelicalism is a type of Christianity that focuses on personal conversion. The Great Awakening was a Protestant revival movement in the northeastern colonies. It happened in the 1730s and 1740s.

The first Puritans in New England required church members to share their conversion experience publicly. Later generations were not as successful in getting new members. The movement began with Jonathan Edwards, a preacher in Massachusetts. He wanted to return to the strict beliefs of the Pilgrims. British preacher George Whitefield and other traveling preachers continued the movement. They traveled across the colonies, preaching in an exciting and emotional way.

Followers of Edwards and similar preachers called themselves "New Lights." Those who disagreed with the movement were called "Old Lights." To promote their ideas, both sides started academies and colleges. These included Princeton and Williams College. The Great Awakening is sometimes called the first truly American event.

The groups that supported the Awakening, like Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists, grew the most. They became the largest American Protestant denominations by the early 1800s. By the 1770s, Baptists were growing quickly in both the North and the South. Groups that opposed or were split by the Awakening, like Anglicans, Quakers, and Congregationalists, did not grow as much.

Religion and the American Revolution

The American Revolution caused problems for some religious groups. The Church of England, for example, had ministers who had sworn loyalty to the King. Quakers were traditionally pacifists (they believed in peace and not fighting). Religious practices suffered in some areas because ministers left or churches were destroyed. But in other areas, religion thrived.

The Revolution hurt the Church of England in America more than any other group. The King of England was the head of the church. The Book of Common Prayer included prayers for the monarch. This meant asking God to protect the King from his enemies. In 1776, these "enemies" were American soldiers, who were neighbors and friends of American Anglicans. Being loyal to the church and its head could be seen as treason to the American cause.

Patriotic American Anglicans did not want to get rid of their prayer book. So, they changed it to fit the new political situation. Another result was that the first independent Anglican Church in the country called itself the Protestant Episcopal Church. This name showed it was separate from the Church of England.

Church and State in Massachusetts

After America gained independence, states had to write their own constitutions. In Massachusetts, it took three years (1778-1780) to create a government plan that voters would accept.

One big debate was whether the state should financially support the church. Ministers and most members of the Congregational Church supported this. Their church had been the official church during colonial times and received public money. Baptists, who had grown strong since the Great Awakening, firmly believed that churches should not get money from the state.

The Constitutional Convention decided to support the church. Article Three allowed a general religious tax. Taxpayers could choose which church their money went to. Even though there was doubt if Article Three was approved by enough voters, Massachusetts authorities declared it adopted in 1780. Similar tax laws also started in Connecticut and New Hampshire.

19th Century Religious Growth

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant movement that started around 1790. It gained strength by 1800. The number of members grew quickly among Baptist and Methodist churches. Their preachers led the movement. It was past its peak by the 1840s. This movement was a reaction against doubt and rational Christianity. It was especially popular with young women. Millions of new members joined existing churches. Many new churches were also formed.

Many converts believed the Awakening meant a new millennial age was coming. The Second Great Awakening encouraged many reform movements. These movements aimed to fix society's problems before the expected Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

The First Great Awakening focused on making existing church members more spiritual. The Second Great Awakening focused on people who did not go to church. It tried to give them a deep feeling of personal salvation. This happened during revival meetings.

A new idea from these revivals was the camp meeting. People would gather in a field or forest for a long religious meeting. They would turn the site into a camp. Singing and preaching were the main activities for several days. The revivals were often very emotional. Some people left the church later, but many became permanent church members. Methodists and Baptists made these meetings a key part of their churches.

During the Second Great Awakening, new Protestant groups appeared. These included Adventism, the Restoration Movement, and groups like Jehovah's Witnesses and Mormonism.

Restoration Movement

The Restoration Movement began in America during the Second Great Awakening in the early 1800s. It aimed to reform the church and unite Christians. Barton W. Stone and Alexander Campbell both developed similar ideas. They wanted to restore the Christian church to the way it was in the New Testament. Both groups believed that church rules (creeds) kept Christians divided. They officially joined together in 1832.

They agreed that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God. They also believed that churches should celebrate the Lord's Supper every first day of the week. They also believed that baptism of adult believers by immersion in water was necessary for Salvation.

The Restoration Movement started as two separate efforts. The first was led by Barton W. Stone in Kentucky. His group simply called themselves Christians. The second was led by Thomas Campbell and his son, Alexander Campbell, in Pennsylvania and Virginia. Because they wanted to avoid all church labels, they used names for Jesus' followers found in the Bible. Both groups wanted to return to the ways of the early churches described in the New Testament.

The Restoration Movement has split into several groups. Three modern groups trace their roots to this movement: Churches of Christ, Christian churches and churches of Christ, and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).

Separation of Church and State

In October 1801, members of the Danbury Baptists Associations wrote a letter to the new president, Thomas Jefferson. Baptists were a minority in Connecticut. They were still required to pay taxes to support the Congregationalist majority. The Baptists found this unfair. They knew Jefferson had his own unique beliefs. They wanted him to help make all religious expression a basic human right, not something the government allowed.

In his reply on January 1, 1802, Jefferson explained the First Amendment's original purpose. He used a phrase that is now very famous: the amendment created a "wall of separation between church and state." This phrase was not well-known at the time. But it has since become a very important idea in American law and politics. The US Supreme Court first used this phrase from Jefferson in 1878, 76 years later.

African American Churches

The Christianity of black people was based on evangelicalism. The Second Great Awakening was very important for the growth of Afro-Christianity. During these revivals, Baptists and Methodists converted many African Americans. However, many were unhappy with how they were treated by white believers. They were also disappointed that many white Baptists and Methodists stopped trying to end slavery after the American Revolution.

When their unhappiness grew, strong black leaders did what was becoming an American custom: they formed new churches. In 1787, Richard Allen and his friends in Philadelphia left the Methodist Church. In 1815, they founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. This church, along with independent black Baptist churches, grew strong as the century went on.

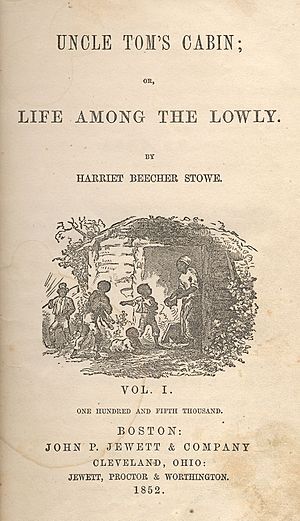

The Abolitionist Movement

The first American movement to end slavery started in 1688. German and Dutch Quakers of Mennonite background in Germantown, Pennsylvania, wrote a strong statement against slavery. They sent it to their Quaker church leaders. Although the Quaker leaders did not act right away, this statement was an early and clear argument against slavery. It helped lead to the banning of slavery among Quakers (1776) and in Pennsylvania (1780).

The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage was the first American group to work against slavery. It was formed in Philadelphia in 1775, mainly by Quakers who strongly opposed slavery for religious reasons.

After the American Revolutionary War, Quaker and Moravian supporters helped convince many slaveholders in the Upper South to free their enslaved people. Theodore Weld, an evangelical minister, and Robert Purvis, a free African American, joined William Lloyd Garrison in 1833. They formed the Anti-Slavery Society. The next year, Weld encouraged students at Lane Theological Seminary to form an anti-slavery group. When the president tried to stop them, the students moved to Oberlin College. Because of the students' anti-slavery stance, Oberlin soon became a very open college and accepted African American students.

After 1840, "abolition" usually referred to ideas like Garrison's. It was a movement led by about 3,000 people. This included free black people and people of color. Many, like Frederick Douglass, Robert Purvis, and James Forten, were important leaders. Abolitionism had strong religious roots. It included Quakers and people who were inspired by the revivals of the Second Great Awakening. This was led by Charles Finney in the North in the 1830s. Belief in abolition led some small church groups, like the Free Methodist Church, to break away from larger denominations.

Evangelical abolitionists founded some colleges. The most famous are Bates College in Maine and Oberlin College in Ohio. Older, well-known colleges like Harvard, Yale, and Princeton generally opposed abolition.

Daniel O'Connell, a Catholic leader from Ireland, supported ending slavery in the British Empire and America. He helped get rights for Catholics in Britain and Ireland. He was a role model for William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison asked him to support American abolitionism. O'Connell, the black abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond, and a priest named Theobold Mayhew organized a petition. It had 60,000 signatures. It asked Irish people in the United States to support abolition. O'Connell also spoke in the United States for abolition.

The Catholic Church in America had long ties to slaveholding areas like Maryland and Louisiana. Even though Pope Gregory XVI strongly condemned slavery in 1839, the American church continued to support slaveholding interests. The Bishop of New York said O'Connell's petition was fake or unwanted foreign interference. The Bishop of Charleston said that while Catholic tradition opposed slave trading, it had nothing against slavery itself. No American bishop supported abolition before the Civil War. During the war, they still allowed slave owners to receive communion.

One historian noted that some churches, like Episcopalians and Lutherans, also accepted slavery. The Anglican Church had been the official church in the South during colonial times. It was connected to wealthy landowners and Southern traditions. While Protestant missionaries of the Great Awakening first opposed slavery in the South, by the early 1800s, Baptist and Methodist preachers in the South had accepted it. This was so they could reach farmers and artisans. By the Civil War, the Baptist and Methodist churches split into regional groups because of slavery.

The abolitionist movement was made stronger by the actions of free African-Americans. Especially important were those in the black church. They argued that old Bible reasons for slavery went against the New Testament. African-American activists and their writings were not often heard outside the black community. However, they influenced some white people who supported them. The first white activist to become famous was William Lloyd Garrison. He was very good at spreading the message. Garrison's efforts to find good speakers led to the discovery of former enslaved person Frederick Douglass. Douglass later became an important activist himself.

Russian Orthodoxy in the US

The main office for the North American Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church moved from Alaska to California in the mid-1800s. It moved again later in the century, this time to New York. This move happened at the same time as many Uniates (Eastern Catholics) joined the Orthodox Church in the eastern United States. This increased the number of Orthodox Christians in America. This happened because of a disagreement between John Ireland, a powerful Roman Catholic Archbishop, and Alexis Toth, an important Ruthenian Catholic priest. Archbishop Ireland refused to accept Father Toth as a priest. This led Father Toth to return to the Orthodox Church of his ancestors. It also led tens of thousands of other Uniate Catholics in North America to join the Orthodox Church, guided by him.

Because of this, Ireland is sometimes jokingly called the "Father of the Orthodox Church in America." These Uniates joined the existing North American diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church. At the same time, many Greeks and other Orthodox Christians were also moving to America. At this time, all Orthodox Christians in North America were united under the authority of the Patriarch of Moscow. This was through the Russian Church's North American diocese. This unity was real because there was no other diocese on the continent then. Under this diocese, led by Bishop (and future Patriarch) Tikhon around 1900, Orthodox Christians of different backgrounds were served. A mission for Syrian-Arabs was also started, led by Saint Raphael of Brooklyn. He was the first Orthodox bishop to be consecrated (made a bishop) in America.

Liberal Christianity

The "secularization of society" means that society became less focused on religion. This is linked to the time of the Enlightenment. In the United States, more people practice religion than in Europe. American culture is also more conservative compared to other Western countries, partly because of its Christian roots.

Liberal Christianity, supported by some religious thinkers, tried to bring new ways of looking at the Bible to churches. This is sometimes called liberal theology. It covers ideas and movements within Christianity in the 1800s and 1900s. New attitudes appeared, and people started to question widely accepted Christian beliefs.

After World War I, Liberalism was the fastest-growing part of the American church. Liberal parts of different church groups were growing. Many seminaries (schools for religious training) taught from a liberal viewpoint. After World War II, the trend started to shift back towards more conservative ideas in America's seminaries and churches.

Christian Fundamentalism

Christian fundamentalism started in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It was a movement to reject the influence of non-religious ideas and critical ways of studying the Bible in modern Christianity. Liberal Protestant groups were denying beliefs that these conservative groups thought were essential. So, fundamentalists wanted to establish the "fundamentals" needed to keep a Christian identity. This is where the term "fundamentalist" comes from.

They especially targeted critical ways of interpreting the Bible. They also tried to stop secular scientific ideas from entering their churches. Fundamentalists grew in different church groups as independent movements. They resisted moving away from traditional Christianity.

Over time, the movement split. The label Fundamentalist was kept by the smaller, stricter groups. Evangelical became the main name for groups that held to the movement's more moderate and original ideas.

Growth of Roman Catholicism

By 1850, Roman Catholics became the largest single religious group in the country. Between 1860 and 1890, the number of Roman Catholics in the United States tripled because of immigration. By the end of that decade, it reached seven million. These Catholic immigrants came from Ireland, Southern Germany, Italy, Poland, and Eastern Europe. This large number of immigrants eventually gave the Roman Catholic Church more political power and a bigger cultural presence. This led to a growing fear of a Catholic "threat." As the 1800s went on, the hostility lessened. Protestant Americans realized that Roman Catholics were not trying to take control of the government. However, fears of too much "Catholic influence" on the government continued into the 1900s.

Catholic Church and Labor Unions

The Catholic Church played a big role in shaping America's labor movement. From the start of major immigration in the 1840s, the Church in the United States was mostly in cities. Its leaders and members were usually from the working classes. In the second half of the 1800s, anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and anti-union feelings came together in Republican politics. So, Catholics were drawn to unions and the Democratic Party.

The Knights of Labor was the earliest labor organization in the United States. In the 1880s, it was the largest labor union in the US. It's thought that at least half of its members were Catholic, including Terence Powderly, its president from 1881.

In Rerum novarum (1891), Pope Leo XIII criticized the concentration of wealth and power. He spoke out against the unfair treatment workers faced. He demanded that workers should have certain rights and safety rules. He supported the right to form voluntary groups, especially praising labor unions. At the same time, he defended private property and spoke against socialism. He also stressed that Catholics needed to form and join unions that were not influenced by non-religious or revolutionary ideas.

Rerum novarum gave new reasons for Catholics to be active in the labor movement. In the U.S., unions were religiously neutral. This meant American Catholics did not need to form separate Catholic unions. American Catholics rarely controlled unions, but they had influence across organized labor. Catholic union members and leaders helped guide American unions away from socialism.

Youth Programs in Churches

In colonial times, children were treated like small adults. But in the 1800s, people started to realize children and youth had special needs. Churches of all sizes began special programs for young people. Protestant theologian Horace Bushnell wrote Christian Nurture (1847). He stressed the importance of understanding and supporting the religious feelings of children and young adults.

Starting in the 1790s, Protestant churches set up Sunday school programs. These were a major way to gain new members. In cities, Protestant church leaders started interdenominational YMCA (and later YWCA) programs in the 1850s. Methodists saw their youth as future activists. They gave them chances to join social justice movements like prohibition. Black Protestant churches, especially after they could form their own separate churches, included their young people directly in the larger religious community. Their youth played a big role in leading the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

White evangelicals in the 1900s started Bible clubs for teenagers. They also tried using music to attract young people. Catholics started a network of parochial schools. By the late 1800s, more than half of their young members probably attended elementary schools run by local churches. Some German Lutherans and Dutch Reformed churches also started parochial schools. In the 1900s, all churches sponsored programs like the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.

20th Century Developments

The Social Gospel Movement

The Social Gospel movement was popular from the 1890s to the 1920s. It called for applying Christian ethics to social problems. This included issues like economic inequality, poverty, racial tensions, slums, poor hygiene, child labor, weak labor unions, bad schools, and the danger of war. Its leaders were mostly connected to the liberal part of the Progressive Movement. Most were theologically liberal. Important leaders included Richard T. Ely, Josiah Strong, Washington Gladden, and Walter Rauschenbusch.

The Social Gospel movement was strongest in the early 1900s. Some scholars say that the terrible events of World War I made many people lose faith in the Social Gospel's ideals. Others argue that World War I actually encouraged the Social Gospellers' efforts to make changes. Ideas from the Social Gospel reappeared in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

Scopes Monkey Trial

The Scopes Monkey Trial was a big public event in 1925. It showed a challenge from modern ideas to Fundamentalist beliefs about the Bible. It was a criminal case about Tennessee's Butler Act. This law made it illegal in public schools "to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals." This usually meant the law forbade teaching about evolution. The case was a key moment in the United States' creation-evolution debate.

After the Butler Act passed, the American Civil Liberties Union paid for a test case. A high school teacher in Dayton, Tennessee named John Scopes intentionally broke the law. The trial was highly publicized. Two famous lawyers of the time faced each other: William Jennings Bryan for the prosecution and Clarence Darrow for Scopes. Scopes was found guilty, but the charges were later dropped due to a small legal error. The result was a setback for the Fundamentalist effort to stop the teaching of evolution for many years.

Evangelicalism's Rise

In the U.S. and around the world, there has been a clear rise in the evangelical part of Protestant churches. Especially those that were more focused on evangelical beliefs. At the same time, there has been a decline in the more liberal mainstream churches.

The 1950s saw a big growth in the Evangelical church in America. The wealth after World War II in the U.S. also affected the church. Many church buildings were built. The Evangelical church's activities grew along with this physical expansion. In the southern U.S., Evangelicals, led by people like Billy Graham, saw a big increase. This changed the old image of loud country preachers from fundamentalism. The stereotypes slowly changed.

Evangelicals are diverse. They include people like Billy Graham, Chuck Colson, J. Vernon McGee, or Jimmy Carter. They also include institutions like Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary or Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Even though there is diversity among Evangelicals worldwide, they share common beliefs. These include a "high view" of the Bible, belief in Jesus's divinity, the Trinity, salvation by grace through faith, and Jesus's bodily resurrection.

Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism began and grew in 20th-century Christianity. The Pentecostal movement had its roots in Pietism and the Holiness movement. It started with meetings in 1906 at an urban mission on Azusa Street in Los Angeles, California.

The Azusa Street Revival was led by William J. Seymour, an African American preacher. It started on April 14, 1906, at the African Methodist Episcopal Church and continued until about 1915. The revival was known for exciting spiritual experiences. These included speaking in tongues, dramatic worship services, and people of different races mixing together. It was the main reason for the rise of Pentecostalism. It spread through those who believed they experienced miraculous acts of God.

Many Pentecostals use the term "Evangelical". Others prefer "Restorationist". Within traditional Pentecostalism, there are three main types: Wesleyan-Holiness, Higher Life, and Oneness.

Pentecostalism later led to the Charismatic movement within already established churches. Some Pentecostals use the two terms interchangeably. Pentecostalism claims more than 250 million followers worldwide. When Charismatics are added, the number nearly doubles to about a quarter of the world's 2 billion Christians.

Modern Roman Catholicism

By the early 1900s, about one-sixth of the United States population was Roman Catholic. Modern Roman Catholic immigrants come to the United States from the Philippines, Poland, and Latin America, especially from Mexico. This multiculturalism and diversity affected Catholicism in the United States. For example, many dioceses (church districts) have Mass in both Spanish and English.

Eastern Orthodoxy in the US

Many people have moved from Greece and the Near East in the last hundred years. This has increased the number of Orthodox Christians in the United States and other places. Almost all Orthodox nationalities are represented in the United States. These include Greek, Arab, Russian, Serbian, Albanian, Ukrainian, Romanian, and Bulgarian.

Many Orthodox church movements in the West are divided by ethnicity. As older members from specific ethnic groups pass away, more churches are opening to new converts. In the past, these converts would have had to learn the language and culture of the Orthodox group to convert properly. Now, many churches hold services in English, Spanish, or Portuguese.

Russian Orthodoxy in the 20th Century

In 1920, Patriarch Tikhon issued a decree. It said that church districts of the Russian Church that were cut off from the main church authority should be managed independently. This was until normal relations could start again. Because of this, the North American diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church (known as the "Metropolia") continued to govern itself. Financial problems after the Russian Revolution caused some confusion. As a result, other national Orthodox communities in North America turned to their home countries for leadership.

A group of bishops who left Russia after the Russian Civil War met in Yugoslavia. They supported the monarchy. This group claimed to speak for the entire "free" Russian church. Patriarch Tikhon officially dissolved this group in 1922. He then appointed Metropolitans Platon and Evlogy as leaders in America and Europe. Both continued to have some contact with the group in Yugoslavia.

Between the World Wars, the Metropolia worked with an independent group. This group later became known as Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR). The two groups eventually went their separate ways. ROCOR moved its headquarters to North America after World War II. It claimed authority over all Russian parishes in North America, but did not fully achieve it. The Metropolia, as a former diocese of the Russian Church, looked to the Russian Church as its highest authority. However, it was temporarily cut off due to the communist government in Russia.

After World War II, the Patriarchate of Moscow tried to regain control over these groups, but was not successful. After talking with Moscow again in the early 1960s, the Metropolia was granted autocephaly (self-governance) in 1970. It became known as the Orthodox Church in America. However, not all Orthodox churches recognize this self-governance. The Ecumenical Patriarch (who leads the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America) and some other groups have not accepted it. Still, the Ecumenical Patriarch, the Patriarch of Moscow, and the other groups are in communion (they recognize each other). Relations between the OCA and ROCOR have also improved. The Patriarchate of Moscow gave up its claims to authority in the United States and Canada.

National Church Associations

The Federal Council of Churches, founded in 1908, was the first major sign of a growing movement for unity among Christians in the United States. It worked to change public and private policies. It especially focused on helping those living in poverty. It created a widely discussed Social Creed. This was like a "bill of rights" for people seeking improvements in American life.

In 1950, the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA (known as National Council of Churches, or NCC) greatly expanded Christian cooperation. It was a merger of the Federal Council of Churches and other church ministries. In 2012, the NCC was a joint effort of 35 Christian denominations in the United States. It had 100,000 local churches and 40,000,000 members. Its member churches include Mainline Protestant, Orthodox, African-American, Evangelical, and historic Peace churches. The NCC played an important role in the Civil Rights Movement. It also helped publish the widely used Revised Standard Version of the Bible. The organization is based in Washington, DC.

Carl McIntire helped organize the American Council of Christian Churches (ACCC) in September 1941. It now has 7 member groups. It was a more active and fundamentalist organization. It was set up to oppose what became the National Council of Churches. The organization is based in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

A national conference for United Action Among Evangelicals was called for April 1942. The National Association of Evangelicals was formed by 147 people who met in St. Louis, Missouri, on April 7–9, 1942. The organization was first called the National Association of Evangelicals for United Action. It was soon shortened to the National Association of Evangelicals (NEA). There are currently 60 denominations with about 45,000 churches in the organization. It is based in Washington, D.C.

Oregon Compulsory Education Act

After World War I, some states worried about the influence of immigrants and "foreign" values. They looked to public schools for help. These states wrote laws to use schools to promote a common American culture.

In 1922, the Masonic Grand Lodge of Oregon supported a bill. It would require all school-aged children to attend public schools. With support from the Ku Klux Klan and Democratic Governor Walter M. Pierce, the Compulsory Education Act passed. Its main goal was to close Catholic schools in Oregon. But it also affected other private and military schools. The law's legality was challenged in court. The Supreme Court eventually struck it down in Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) before it could take effect.

The law made Catholics very angry. They organized locally and nationally to fight for the right to send their children to Catholic schools. In Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925), the United States Supreme Court said Oregon's Compulsory Education Act was unconstitutional. This ruling has been called "the Magna Carta of the parochial school system."

Civil Rights Movement and Churches

African-American churches were central to community life. So, they played a leading role in the Civil Rights Movement. Their history as a meeting point for the Black community and a link between Black and White worlds made them perfect for this purpose.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was one of many famous Black ministers in the movement. He helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (1957) and was its first president. In 1964, King received the Nobel Peace Prize. This was for his efforts to end segregation and racial discrimination. He used non-violent civil disobedience. King was killed in 1968.

Ralph Abernathy, Bernard Lee, Fred Shuttlesworth, C.T. Vivian, and Jesse Jackson are among many other notable minister-activists. They were especially important during the later years of the movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

See also

- Catholic social activism in the United States

- Christianity in the United States

- History of religion in the United States

- History of Roman Catholicism in the United States

- Religion in the United States