History of the Soviet Union (1964–1982) facts for kids

| 1964–1982 | |

Leonid Brezhnev speaking at 18th Komsomol Congress opening (25 April 1978)

|

|

| Preceded by | History of the Soviet Union (1953–1964) |

|---|---|

| Including | Cold War |

| Followed by | History of the Soviet Union (1982–1991) |

| Leader(s) | Leonid Brezhnev |

The Brezhnev Era describes the time from 1964 to 1982 when Leonid Brezhnev led the Soviet Union (USSR). This period started with strong economic growth and good times. But over time, problems grew in society, politics, and the economy. Because of this, people often call it the "Era of Stagnation" (meaning things stopped growing or improving much).

In the 1970s, the Soviet Union and the United States tried to improve their relationship. This was called "détente", which means easing tensions. The hope was that the Soviet Union would make economic and democratic changes. However, big changes didn't happen until Mikhail Gorbachev became leader in 1985.

Nikita Khrushchev was removed from his top leadership roles on October 14, 1964. This happened because his reforms didn't work well, and he didn't respect the Party's rules. Brezhnev took over as the main leader, and Alexei Kosygin became the head of the government. Other important leaders like Anastas Mikoyan (later Nikolai Podgorny), Andrei Kirilenko, and Mikhail Suslov joined them. Together, they formed a "collective leadership." This was different from Khrushchev's style, where one person made most decisions.

The new leaders first aimed to make the Soviet Union stable and calm its people. They succeeded in this. They also tried to make the economy grow faster, as it had slowed down under Khrushchev. In 1965, Kosygin started some reforms to give local businesses more control. These reforms helped the economy at first. But some powerful Party members stopped them. They worried the reforms would make the Party less important. No other big economic changes happened during Brezhnev's time. By the time Brezhnev died in 1982, the Soviet economy had almost stopped growing.

The focus on stability led to a "gerontocracy" (rule by older people). Political corruption also became common. Brezhnev didn't start any big campaigns to fight corruption. However, a large military buildup in the 1960s helped the Soviet Union become a superpower. The Brezhnev Era ended with his death on November 10, 1982.

Contents

Politics in the Brezhnev Era

Collective Leadership and Power Shifts

After a long struggle, Khrushchev was removed from power in October 1964. He was criticized for his failed reforms and for making decisions alone. The Party leaders were tired of his style. They believed in a "collective leadership" where decisions were made together. Leonid Brezhnev became the main Party leader, and Alexei Kosygin became the head of the government. Other key figures like Mikhail Suslov, Andrei Kirilenko, and Anastas Mikoyan (later Nikolai Podgorny) also gained power. They worked together as a team.

At first, people called the leadership "Brezhnev–Kosygin." They seemed to have equal power. But after Kosygin's economic reforms in 1965, his influence decreased. Brezhnev's power grew stronger. Later, Podgorny became the second most powerful person in the Soviet Union.

Brezhnev wanted to remove Podgorny from the leadership by 1970. This would make Brezhnev the head of state and increase his power. But Brezhnev couldn't get enough votes from other leaders. Removing Podgorny would weaken the idea of collective leadership itself. Podgorny actually gained more power in the early 1970s. This was partly because some Soviet officials didn't like Brezhnev's friendly approach to Yugoslavia and his talks with Western countries.

However, Brezhnev became much stronger in the mid-1970s. By 1977, he had enough support to remove Podgorny from his position. Podgorny's removal also reduced Kosygin's role in daily government work. After this, rumors spread that Kosygin would retire due to poor health. Nikolai Tikhonov, a close ally of Brezhnev, took over as head of government in 1980.

Podgorny's removal didn't end the idea of collective leadership. Mikhail Suslov continued to write about it. Towards the end of Brezhnev's rule, he was seen as too old to handle all his duties. So, a new position was created: "First Deputy Chairman" of the Supreme Soviet, similar to a vice president. Vasili Kuznetsov, at 76, was appointed to this role. As Brezhnev's health worsened, the collective leadership became even more important in daily decisions. So, when Brezhnev died, the power balance didn't change much. Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko continued to rule in a similar way.

Assassination Attempt on Brezhnev

On January 22, 1969, a former Soviet soldier named Viktor Ilyin tried to assassinate Brezhnev. He fired shots at a car carrying Brezhnev through Moscow. Brezhnev was not hurt. But the shots killed a driver and injured some famous cosmonauts who were also in the motorcade. Ilyin was caught and questioned by Yuri Andropov, who was then the head of the KGB. Ilyin was sent to a mental hospital instead of being given the death penalty.

Defense Policy and Military Power

In 1965, the Soviet Union started a large military buildup. They increased both their nuclear and regular weapons. Soviet leaders believed a strong military would help them negotiate with other countries. It would also make the Eastern Bloc safer. By the early 1970s, the Soviet Union had as many nuclear weapons as the United States. This helped them become a superpower.

Some of Brezhnev's advisors said he was worried about the rising military spending in the 1960s. Brezhnev even argued with top military leaders, like Marshal Andrei Grechko, the Minister of Defense. In the early 1970s, Brezhnev tried to convince the military to spend less. He asked why the Soviet Union should "exhaust" its economy if it couldn't match the West militarily. This question was never answered. When Grechko died in 1976, Dmitriy Ustinov became Defense Minister. Ustinov, a friend of Brezhnev, stopped any attempts to cut military spending. In his later years, Brezhnev's declining health meant he lacked the energy to reduce defense spending.

At the 23rd Party Congress in 1966, Brezhnev said the Soviet military was strong enough to defend the country. By the early 1970s, the Soviet Union had achieved nuclear equality with the United States. In 1977, Brezhnev stated that the Soviet Union did not want to be superior in nuclear weapons or military power. In his last meeting with military leaders in October 1982, Brezhnev emphasized not overspending on the military. This policy continued under his successors, Andropov, Konstantin Chernenko, and Mikhail Gorbachev.

Stability and Control

Brezhnev's time in office became known for its stability. But early on, he replaced many regional leaders and Politburo members. This was a common way for Soviet leaders to strengthen their power. Some Politburo members who lost their positions during this time included Gennady Voronov and Dmitry Polyansky. They were seen as part of the "Kosygin group." In their place came new members like Andrei Grechko (Defense Minister), Andrei Gromyko (Foreign Minister), and Yuri Andropov (KGB Chairman). These changes stopped in the late 1970s.

Brezhnev presented himself as a moderate leader. He was not as radical as Kosygin or as conservative as Alexander Shelepin. Brezhnev allowed Kosygin's economic reforms to begin. He also took control of Soviet agriculture. Brezhnev believed that improving the existing system was better than completely reorganizing it.

By the late 1960s, Brezhnev spoke about "renewing" Party officials. But he didn't want to risk upsetting lower-level officials. The Politburo saw stability as a way to avoid the harsh purges of Joseph Stalin's time and Khrushchev's constant changes. They believed stability would show the world how good communism was. While some reforms were considered, the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia weakened the reform movement. This led to a period of strong stability in the government. It also meant less cultural freedom, and many underground publications (samizdats) were shut down.

Rule by the Elderly: Gerontocracy

After the Politburo changes ended in the mid-to-late 1970s, the Soviet leadership became a gerontocracy. This means that the rulers were much older than most of the adult population.

The "Brezhnev generation" were people who rose to power after Joseph Stalin's Great Purge in the late 1930s. Stalin had many older officials executed or exiled. This opened up jobs for a younger generation. These people, like Mikhail Suslov, Alexei Kosygin, and Brezhnev, would lead the country until Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985. Most of them came from peasant or working-class backgrounds.

The average age of Politburo members was 58 in 1961, but it rose to 71 in 1981. The average age in the Central Committee also increased. Young politicians like Fyodor Kulakov and Grigory Romanov were seen as possible future leaders. But none of them got close to the top. By the time Brezhnev died, the Soviet leadership was described as "lacking physical and intellectual vigor."

The New 1977 Constitution

During his time, Brezhnev was also in charge of the commission that created a new constitution. This commission had 97 members, including Konstantin Chernenko. Brezhnev wanted to weaken Premier Alexei Kosygin's influence. The new constitution was a middle ground, not strongly against Stalin or for him. It followed many of the same ideas as earlier constitutions.

The main difference was that it officially recognized the changes the Soviet Union had gone through since the 1936 Soviet Constitution. For example, it called the Soviet Union an "advanced industrial society". This document showed both the achievements and the limits of moving away from Stalin's rule. It improved the rights of individuals but also strengthened the Party's control.

Brezhnev's Later Years

In his later years, Brezhnev developed a "cult of personality". This means he was praised excessively, and he gave himself many top military awards. The media called him a "dynamic leader and intellectual giant." He even won a Lenin Prize for Literature for his three autobiographical novels, known as Brezhnev's trilogy. These awards were meant to make him seem more powerful. When Alexei Kosygin died in December 1980, state newspapers delayed reporting his death until after Brezhnev's birthday celebration. In reality, Brezhnev's health and mental abilities had been declining since the 1970s.

Brezhnev approved the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, just as he had approved the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. In both cases, he wasn't the strongest supporter of military action. Many top Soviet leaders kept Brezhnev as General Secretary so their own careers wouldn't be affected by a new leader. Others, like Dmitriy Ustinov (Defense Minister), Andrei Gromyko (Foreign Minister), and Mikhail Suslov (Party Secretary), feared that removing Brezhnev would cause a leadership crisis. So, they helped keep things as they were.

Brezhnev stayed in office because of pressure from his Politburo colleagues. But in practice, a collective leadership led by Suslov, Ustinov, Gromyko, and Yuri Andropov governed the country. Konstantin Chernenko also gained influence due to his close ties with Brezhnev. As Brezhnev's health worsened, Andropov started a major anti-corruption campaign. On November 10, 1982, Brezhnev died. He received a large state funeral and was buried five days later.

Economy in the Brezhnev Era

The 1965 Economic Reform

The 1965 Soviet economic reform, often called the "Kosygin reform," aimed to change how the Soviet economy was managed. It happened between 1965 and 1971. Announced in September 1965, it had three main parts:

- Bringing some control back to central government ministries.

- Giving businesses more freedom and incentives for good performance.

- A major change to how prices were set.

These changes were meant to fix problems in the Soviet economy. But the reform didn't try to completely change the system; it tried to improve it slowly. The results were mixed. Experts still debate why it didn't fully succeed. One reason was that giving businesses more freedom while also centralizing control created problems. Also, instead of letting the market set prices, government officials were in charge of it. This meant the market-like system didn't really work. Despite this, the period of the Eighth Five-Year Plan (1968–1970) is seen as one of the most successful for the Soviet economy, especially for consumer goods.

The idea of making the economy more market-based was seen as too radical after the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia. Later, Nikolai Ryzhkov, a future head of government, said that the 1965 reform had "sad experiences" and that things got worse after it was stopped.

The Era of Stagnation

| Period | GNP (according to the CIA) |

NMP (according to Grigorii Khanin) |

NMP (according to the USSR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960–1965 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 6.5 |

| 1965–1970 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 7.7 |

| 1970–1975 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 5.7 |

| 1975–1980 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 4.2 |

| 1980–1985 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 3.5 |

The "Era of Stagnation" is a term used by Mikhail Gorbachev. Many economists see it as a difficult time for the Soviet economy. It was caused by too much central control and a slow government bureaucracy. As the economy grew, the number of decisions for planners in Moscow became too much to handle. This led to lower worker productivity. The slow government rules made it hard for businesses to communicate freely and respond quickly to problems.

During the late Brezhnev Era, political corruption also increased. Officials often faked numbers to show they met government goals. This made the planning crisis even worse. With growing economic problems, skilled workers were often paid more than planned. Unskilled workers often arrived late and didn't work hard. The government couldn't stop this because there was no unemployment. Factories and offices had workers who didn't put much effort into their jobs. This led to a "work-shy workforce" in the Soviet Union.

Failed Reforms of 1973 and 1979

Kosygin started the 1973 Soviet economic reform to give more power to regional planners. But this reform was never fully put into action. Leaders complained it hadn't even started by the time of the 1979 reform. The 1979 Soviet economic reform aimed to improve the struggling Soviet economy. It wanted to give even more power to central government ministries. This reform also failed to be fully implemented. When Kosygin died in 1980, his successor, Nikolai Tikhonov, mostly abandoned it. Tikhonov said the reform would be carried out during the next five-year plan (1981–1985). But it never happened. This reform is seen as the last major attempt to fix the Soviet economy before Mikhail Gorbachev's big changes.

Kosygin's Resignation

After Nikolai Podgorny was removed, rumors spread that Kosygin would retire due to poor health. While Kosygin was sick, Brezhnev appointed Nikolai Tikhonov, a conservative, as First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Tikhonov then reduced Kosygin's role. For example, Tikhonov, not Kosygin, presented the Soviet economic plan in June 1980. After Kosygin resigned in 1980, Tikhonov, at 75, became the new head of government. Towards the end of his life, Kosygin worried that the next five-year plan (1981–1985) would completely fail. He believed the current leaders were unwilling to reform the struggling Soviet economy.

Foreign Relations in the Brezhnev Era

Relations with Western Countries

Alexei Kosygin, the Soviet Premier, tried to challenge Brezhnev's right to represent the country abroad. Kosygin believed this role should belong to the Premier, like in non-communist countries. This happened for a short time. But later, Brezhnev gained more power, and Kosygin was rarely seen outside the Second World (communist countries). Kosygin did lead the Soviet delegation at the Glassboro Summit Conference in 1967 with U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson. They discussed the Vietnam War, the Six-Day War, and the arms race. After the summit, Kosygin went to Cuba and met Fidel Castro, who was angry at the Soviet Union.

Détente, meaning the easing of strained relations, was a key part of Soviet foreign policy from 1969 to 1974. It meant "ideological co-existence" but not an end to competition between capitalist and communist societies. This policy helped improve relations between the Soviet Union and the United States. Several agreements on arms control and trade were signed during this time.

One success was when Willy Brandt became the leader of West Germany in 1969. Tensions between West Germany and the Soviet Union began to ease. Brandt's "Ostpolitik" (Eastern policy) and Brezhnev's détente led to the signing of the Moscow and Warsaw Treaties. West Germany recognized the borders set after World War II, including East Germany as an independent state. Relations continued to improve, reducing the bad feelings many Soviets had towards Germany.

However, not all efforts were successful. The 1975 Helsinki Accords, a Soviet-led initiative, didn't fully work out as planned. The U.S. government wasn't very interested in the process. Western European negotiators played a key role in creating the treaty. The Soviet Union wanted official acceptance of the post-war European borders. They largely succeeded, with borders being "inviolable" (couldn't be changed by military force). Brezhnev and other Soviet leaders were committed to this treaty, even if it meant making some concessions on human rights and transparency.

Another challenge for Soviet communism in Western countries was the rise of "eurocommunism". Eurocommunists supported Soviet ideals but also individual rights. This new way of thinking made Western countries more skeptical of Soviet communism. For example, the Italian Communist Party said they would defend Italy against any Soviet attack.

Relations between the Soviet Union and Western countries worsened when U.S. President Jimmy Carter condemned the 1979 Soviet intervention in Afghanistan. Carter called it the "most serious danger to peace since 1945." The United States stopped all grain exports to the Soviet Union. They also convinced U.S. athletes not to attend the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. The Soviet Union responded by boycotting the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. The détente policy collapsed. When Ronald Reagan became U.S. president in 1981, he promised to increase U.S. defense spending and take a tougher stance against the Soviet Union. This worried Moscow, and Soviet media accused Reagan of "warmongering."

A embarrassing event for the Soviet Union happened in October 1981. One of its submarines ran aground near a Swedish naval base. Sweden took a strong stance, holding the submarine for two weeks. Sweden also said that radiation was detected from the submarine, suggesting it carried nuclear missiles. Moscow denied this and accused Sweden of spying.

Relations with China

After Khrushchev was removed and the Sino-Soviet split (a major disagreement between the Soviet Union and China) happened, Alexei Kosygin was the most hopeful Soviet leader about improving relations with China. Yuri Andropov was skeptical, and Brezhnev didn't say much. Kosygin found it hard to understand why the two countries were fighting. China saw the new Soviet leaders as having the same "revisionist" ideas as Khrushchev. At first, the new Soviet leadership blamed Khrushchev for the split, not China. Both Brezhnev and Kosygin wanted to improve relations. When Kosygin met Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in 1964, Kosygin found him in a "excellent mood." However, early hopes for better relations fell apart when Zhou accused Kosygin of acting like Khrushchev.

When Kosygin suggested to Brezhnev that it was time to make up with China, Brezhnev replied, "If you think this is necessary, then you go by yourself." Kosygin visited Beijing on his way to Vietnam in February 1965 and met Zhou. They solved smaller issues, agreeing to increase trade and celebrate the 15th anniversary of their alliance. Kosygin was told that full reconciliation might take years. In his report, Kosygin noted Zhou's moderate stance and believed he was open to serious talks. Kosygin returned to Beijing and met Mao Zedong on February 11. Mao criticized Kosygin and the Soviet leadership for their "revisionist" behavior. This was Mao's last meeting with a Soviet leader.

The Cultural Revolution in China caused relations to completely break down. Moscow and other communist states saw it as "simple-minded insanity." Chinese Red Guards called the Soviet Union "revisionists" and "the new Hitler." They accused the Soviets of preparing for war against China. Moscow responded by accusing China of false socialism and plotting with the U.S. This tension led to small fights along the border. Brezhnev condemned China's "frenzied anti-Sovietism" and asked Zhou Enlai to normalize relations. In 1972, U.S. President Richard Nixon visited Beijing to restore relations with China. This seemed to confirm Soviet fears of a U.S.-China alliance. Relations between Moscow and Beijing remained very hostile throughout the 1970s. Even after Mao Zedong's death, there was no sign of improvement.

Relations with the Eastern Bloc

The Soviet Union's policy towards the Eastern Bloc (communist countries in Eastern Europe) didn't change much after Khrushchev. These countries were seen as a necessary buffer zone between NATO and the Soviet Union. The Brezhnev government was cautious about reforms, especially after the Prague Spring in 1968. János Kádár, the leader of Hungary, started reforms similar to Kosygin's 1965 economic reform. These reforms were protected by Kosygin. Polish leader Władysław Gomułka was replaced by Edward Gierek in 1970. Gierek tried to improve Poland's economy by borrowing money from Western countries. The Soviet leadership approved these economic experiments. They wanted to reduce their large subsidy program to the Eastern Bloc, which involved cheap oil and gas exports.

However, not all reforms were supported. Alexander Dubček's political and economic changes in Czechoslovakia led to a Soviet-led invasion in August 1968. Not everyone in the Soviet leadership was eager for military action. Brezhnev was cautious, and Kosygin reminded leaders of the consequences of the Soviet crackdown on the 1956 Hungarian revolution. After the invasion, the Brezhnev Doctrine was introduced. It stated that the Soviet Union had the right to intervene in any socialist country that was moving away from communism. This doctrine was condemned by Romania, Albania, and Yugoslavia. As a result, the worldwide communist movement became more diverse, and the Soviet Union lost its role as the sole "leader." Brezhnev explained this doctrine in a speech in November 1968:

When forces that are hostile to socialism try to turn the development of some socialist country towards capitalism, it becomes not only a problem of the country concerned, but a common problem and concern of all socialist countries.

—Brezhnev, Speech to the Fifth Congress of the Polish United Workers' Party in November 1968

On August 25, 1980, the Soviet Politburo created a commission to look into the political crisis in Poland. The commission included important figures like Dmitriy Ustinov (Defense Minister), Andrei Gromyko (Foreign Minister), Yuri Andropov (KGB Chairman), and Konstantin Chernenko. After only three days, the commission suggested a possible Soviet military intervention. Troops and tanks were moved to the Soviet–Polish border. However, the Soviet leadership decided not to intervene in Poland. Stanisław Kania, the Polish leader, suggested introducing martial law in Poland. Erich Honecker, the East German leader, supported the Soviet decision and called for a meeting of Eastern Bloc leaders. When they met, Brezhnev decided it was better to leave Poland's internal matters alone for now. He told the Polish delegation that the USSR would only intervene if asked.

As historian Archie Brown notes, "Poland was a special case." The Soviet Union had intervened in Democratic Republic of Afghanistan the year before. The tough policies of the Reagan administration and the strong opposition movement in Poland were major reasons why the Politburo pushed for martial law instead of an intervention. When Wojciech Jaruzelski became Prime Minister of Poland in February 1980, both the Soviet leadership and many Poles supported him. But Jaruzelski struggled to balance the demands of the USSR and the Polish people. Martial law was declared on December 13, 1981.

In Brezhnev's final years, and after his death, the Soviet leadership faced internal problems. They had to allow Eastern Bloc governments to adopt more nationalistic communist policies. This was to prevent unrest like in Poland from spreading to other communist countries. Yuri Andropov, Brezhnev's successor, said that maintaining good relations with the Eastern Bloc was the most important part of Soviet foreign policy.

Relations with the Third World

You see, even in the jungles they want to live in Lenin's way!

The Soviet Union called all self-proclaimed African socialist states and South Yemen in the Middle East "States of Socialist Orientation." Many African leaders were influenced by Marxism and Leninism. Some Soviet experts disagreed with this policy. They argued that these countries hadn't built a strong enough capitalist base to be called socialist. According to historian Archie Brown, these experts were right. No true socialist states were ever established in Africa, though Mozambique came close.

When the Ba'ath Party in Iraq took control of the Iraq Petroleum Company, the Iraqi government sent Saddam Hussein to negotiate a trade agreement with the Soviet Union. Hussein got a trade agreement and a friendship treaty. When Kosygin visited Iraq in 1972, he and Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, the President of Iraq, signed the Iraqi–Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Co-operation. This alliance also forced the Iraqi government to temporarily stop persecuting the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP). The ICP even got two ministerial positions. Relations worsened in 1976 when Iraq started a campaign against the ICP. Despite Brezhnev's pleas, several Iraqi communists were executed.

After the Angolan War of Independence in 1975, the Soviet Union's role in Third World politics grew a lot. Some regions were important for Soviet security. Others were important for spreading Soviet socialism. According to one Soviet writer, the struggle for national liberation was a key part of Soviet ideology. So, it became a key part of Soviet diplomacy in the Third World.

Soviet influence in Latin America increased after Cuba became a communist state in 1961. Moscow welcomed the Cuban revolution because it was a communist government established by local forces, not the Red Army. Cuba also became the Soviet Union's "front man" for promoting socialism in the Third World. By the late 1970s, Soviet influence in Latin America was seen as a crisis by some U.S. politicians. The Soviet Union established diplomatic and economic ties with several countries in the 1970s. Mexico and some Caribbean countries also formed stronger ties with Comecon, an Eastern Bloc trading organization. Soviet thinkers saw this growing Soviet presence as part of the "anti-imperialist struggle for democracy and social justice."

The Soviet Union also played a key role in the fight against the Portuguese Empire and the struggle for black majority rule in Southern Africa. Control of Somalia was important to both the Soviet Union and the United States because of its location near the Red Sea. After the Soviets broke relations with Siad Barre's government in Somalia, they supported the Derg government in Ethiopia in their war against Somalia. Because the Soviets changed sides, Barre expelled all Soviet advisors, ended his friendship treaty with the Soviet Union, and allied with the West. The United States took the Soviet Union's place in the 1980s after Somalia lost the Ogaden War.

In Southeast Asia, Nikita Khrushchev had initially supported North Vietnam. But as the war grew, he urged North Vietnam to give up its goal of freeing South Vietnam. He refused to help North Vietnam and told them to negotiate. Brezhnev, after taking power, started helping the communist resistance in Vietnam again. In February 1965, Kosygin traveled to Hanoi with Soviet military and economic experts. During this visit, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson allowed U.S. bombing raids on North Vietnam. After the war, Soviet aid became very important for Vietnam's economy. For example, in the early 1980s, the Soviet Union supplied 20–30% of the rice eaten by Vietnamese people. Since Vietnam didn't have its own weapons industry during the Cold War, the Soviet Union helped them with weapons and supplies during the Sino-Vietnamese War.

The Soviet Union supported Vietnam in its 1978 invasion of Cambodia. This invasion was seen by Western countries and China as being directly ordered by the Soviet Union. The USSR also became the biggest supporter of the new government in Cambodia, the People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK). In a 1979 meeting, Jimmy Carter complained to Brezhnev about Vietnamese troops in Cambodia. Brezhnev replied that the people of the PRK were happy about the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge government.

The War in Afghanistan

The government of Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, formed after the Saur Revolution in 1978, followed some socialist policies. But the Soviet Union "never considered" Afghanistan to be truly socialist. The revolution surprised the Soviet leadership and created many problems for them. The People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan, the Afghan communist party, had two opposing groups: the khalqs and the parchams. The Soviet leadership supported the Parcham group. But after the coup, the Khalq group took power. Nur Muhammad Taraki became President and Prime Minister, and Hafizullah Amin became Deputy Prime Minister. The new Khalq government ordered the execution of many Parcham members. To make things worse, Taraki and Amin's relationship turned bad as opposition to their government grew.

On March 20, 1979, Taraki traveled to the Soviet Union. He met with Premier Kosygin, Dmitriy Ustinov (Defense Minister), Andrei Gromyko (Foreign Minister), and Boris Ponomarev to discuss a possible Soviet intervention in Afghanistan. Kosygin opposed the idea. He believed the Afghan leaders had to prove they had the people's support by fighting opposition on their own. But he did agree to increase aid to Afghanistan. When Taraki asked about a military intervention by the Eastern Bloc, Kosygin again told him that Afghan leaders had to survive on their own. However, in a private meeting without Kosygin, the Politburo unanimously supported a Soviet intervention.

In late 1979, Taraki failed to assassinate Amin. In revenge, Amin successfully arranged Taraki's assassination on October 9. Later, in December, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. A KGB unit killed Amin on December 27. Babrak Karmal, the leader of the Parcham group, was chosen by the Soviet leadership to replace Amin. Unfortunately for the Soviets, Karmal didn't turn out to be the leader they expected. He arrested and killed many Khalq members. But with Soviet troops in the country, he had to give in to Soviet pressure and release all Khalq prisoners. Many of these former prisoners were even forced to join the new government. When Brezhnev died, the Soviet Union was still deeply involved in Afghanistan.

Dissident Movement in the Soviet Union

Soviet dissidents and human rights groups were often suppressed by the KGB. Political repression increased during the Brezhnev era. Joseph Stalin even saw a partial return to favor. The two main figures in the Soviet dissident movement were Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov. Despite their fame and support in the West, they didn't get much support from the general population. Sakharov was forced into internal exile in 1979, and Solzhenitsyn was forced out of the country in 1974.

Many dissidents chose to join the Communist Party instead of actively protesting the Soviet system. These dissidents, called "gradualists" by Archie Brown, wanted to change the system slowly from within. The departments of the Central Committee, which were seen as conservative, actually produced many of Mikhail Gorbachev's "new thinkers." These officials had been influenced by Western culture through travel and reading. Many reformers also worked in the country's research institutes.

The Brezhnev-era Soviet government was known for using psychiatry to silence dissent. Many intellectuals, religious figures, and even ordinary people protesting their low living standards were declared mentally ill. They were then sent to mental hospitals.

The success of dissident movements was mixed. Jews who wanted to emigrate from the Soviet Union in the 1970s formed the most successful and organized group. Their success was due to support from abroad, especially from the Jewish community in the United States. Also, this group wasn't trying to change Soviet society; they just wanted to leave for Israel. The Soviet government allowed some Jews to emigrate to improve relations with Western countries. The number of emigrants dropped when Soviet–American tensions increased in the late 1970s. But it rose again in 1979, reaching 50,000. In the early 1980s, however, the Soviet leadership stopped emigration almost completely.

In 1978, a different kind of dissident movement appeared. A group of unemployed miners led by Vladimir Klebanov tried to form a labor union. They demanded collective bargaining. The main groups of Soviet dissidents, mostly intellectuals, stayed away from this effort. Klebanov was soon sent to a mental institution. Another attempt a month later to form a union for white-collar workers was also quickly broken up by authorities. Its founder, Vladimir Svirsky, was arrested.

Every time when we speak about Solzhenitsyn as the enemy of the Soviet regime, this just happens to coincide with some important [international] events and we postpone the decision.

Overall, the dissident movement had bursts of activity. For example, during the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, several people demonstrated in Red Square in Moscow. With safety in numbers, dissidents interested in democratic reform could show themselves. But the demonstration and the short-lived group were eventually suppressed. The movement gained new life when the Soviet Union signed the Helsinki Accords. Several Helsinki Watch Groups were formed across the country. But they were often repressed and shut down. Because the Soviet government was so strong, many dissidents found it hard to reach a "wide audience." By the early 1980s, the Soviet dissident movement was in disarray. The country's most famous dissidents had been exiled, imprisoned, or sent to labor camps (Gulags).

The anti-religious policies of Khrushchev were softened by Brezhnev and Kosygin. Most Orthodox churches had clergy who were loyal to the state, often linked to the KGB. State propaganda focused more on promoting "scientific atheism" rather than actively persecuting believers. However, minority faiths continued to be harassed. The continued strength of Islam in the Central Asian republics was particularly troubling to authorities. This was made worse by their closeness to Iran, which came under the control of a strict Islamic government in 1979. This new Iranian government was hostile to both the United States and the Soviet Union.

Soviet Society in the Brezhnev Era

Ideology and Beliefs

Many people believe that Soviet society reached its mature stage under Brezhnev's rule. Historians Edwin Bacon and Mark Sandle noted that a "social revolution" happened in the Soviet Union during his 18 years in power. Soviet society became more modern and urban. People became better educated and more professional. Unlike earlier times with "terrors, disasters, and conflicts," the Brezhnev era was a period of continuous development. Higher education grew four times between the 1950s and 1980s. This was called the "scientific-technological revolution." Also, women made up half of the country's educated specialists.

After Khrushchev's controversial claim in 1961 that pure communism could be reached "within 20 years", the new Soviet leadership promoted the idea of "developed socialism". Brezhnev announced the start of the era of developed socialism in 1971. Developed socialism was described as socialism that had reached "developed conditions." It was the result of "perfecting" the socialist society created by the Bolsheviks. In short, developed socialism was just another step towards communism. This idea became the main belief of the Brezhnev government. It helped explain the Soviet Union's situation. However, the theory also said that the Soviet Union was free of crises, which turned out to be wrong. So, Yuri Andropov, Brezhnev's successor, started to move away from Brezhnev's ideas. He introduced more realistic beliefs, though he kept "developed socialism" as part of the state's main ideology.

Culture and Daily Life

During the Brezhnev era, pressure from the public forced Soviet leaders to change some cultural policies. But the basic rules of the Communist system stayed the same. Rock music and jeans, which were once criticized as Western, became more accepted. The Soviet Union even started making its own jeans in the 1970s. However, Soviet youth still wanted Western products more. The Soviet black market thrived, and "fake Western jeans" became very popular. Western rock groups like The Beatles remained very popular, even though Soviet officials were wary of them. Soviet rock music developed and became a way to express disagreement with the Soviet system. Vladimir Vysotsky, Alexander Galich, and Bulat Okudzhava became famous rock musicians. Their songs often criticized the country's Stalinist past and its undemocratic system.

Standard of Living

From 1964 to 1973, the Soviet GDP per person (in U.S. dollars) increased. Over the 18 years Brezhnev ruled, the average income per person grew by half. In the first half of his rule, income per person grew by 3.5% each year. This was slightly less than in Khrushchev's last years. But over time, people were better off than under Khrushchev. Consumption per person rose by about 70% under Brezhnev. Most of this growth happened before 1973. The increase in consumer goods in the early Brezhnev era was largely due to the 1965 Kosygin reform.

When the Soviet economy slowed down in the 1970s, the government focused on improving the standard of living and housing quality. The standard of living in Russia fell behind that of Georgia and Estonia. This made many Russians feel that government policies were hurting them. To gain support, the Soviet leadership under Brezhnev expanded social benefits. This did lead to a small increase in public support for the government.

In terms of advanced technology, the Soviet Union was far behind the United States, Western Europe, and Japan. Old electronics were still used in the USSR long after they were outdated elsewhere. Many factories in the 1980s still used machines from the 1930s. A Soviet general admitted in 1982 that "in America, even small children play with computers. We do not even have them in all the offices of the Defense Ministry." Soviet manufacturing was not only old but also very inefficient. It often needed 2 to 3 times more workers than factories in the U.S.

The Brezhnev era brought material improvements for Soviet citizens. But the Politburo didn't get credit for it. Average citizens took for granted things like cheap consumer goods, food, housing, clothing, healthcare, and transport. People associated Brezhnev's rule more with its problems than its progress. So, Brezhnev didn't earn much affection or respect. Most Soviet citizens couldn't change the system, so they tried to make the best of it.

While investments in consumer goods were lower than planned, the increase in production did improve the Soviet people's standard of living. For example, only 32% of households had refrigerators in the early 1970s. By the late 1980s, 86% had them. Ownership of color televisions increased from 51% in the early 1970s to 74% in the 1980s. However, most civilian services got worse. The physical environment for ordinary citizens declined quickly. Diseases increased because of the failing healthcare system. Living space remained small by Western standards, with the average Soviet citizen living in 13.4 square meters. At the same time, thousands of Moscow residents were homeless. Authorities often checked public places to find people skipping work. Nutrition stopped improving in the late 1970s, and rationing of basic foods returned to some places. Environmental damage and pollution became a growing problem because the government focused on development at any cost. Some areas, like the Kazakh SSR, suffered badly from nuclear weapons testing. While Soviet citizens in 1962 had a higher average life expectancy than people in the United States, it fell by almost five years by 1982.

These effects were not felt equally by everyone. For example, by the end of the Brezhnev era, blue-collar workers had higher wages than professional workers. A secondary-school teacher earned 150 rubles a month, while a bus driver earned 230. Overall, real wages increased from 96.5 rubles a month in 1965 to 190.1 rubles a month in 1985. A small group benefited even more. The state provided daily recreation and annual holidays for hard-working citizens. Soviet trade unions rewarded good workers with beach vacations in Crimea and Georgia. Workers who met their production goals were honored. War veterans could go to the front of shop queues. Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences received special badges and chauffeur-driven cars. These rewards helped some people find good jobs, but they didn't stop society from declining. Urbanization led to unemployment in the agricultural sector, as many workers left villages for towns.

Overall, women had made significant social progress since the 1917 revolution. By the Brezhnev era, many women were the main earners in their families. Some professions, like medicine, had many female workers. However, most of the best jobs, including in academics, government, and the military, were still mostly held by men.

The agricultural sector continued to perform poorly. By Brezhnev's last year, food shortages were becoming very frequent. It was particularly embarrassing that even bread was rationed, a product the government always prided itself on having available. One reason was that consumer demand was too high because food prices were kept artificially low, while incomes had tripled over 20 years. Despite the failure of collective farming, the Soviet government didn't want to import food from the West. This was for national pride and fear of relying on capitalist countries for basic needs.

Social "rigidification" became common. In Stalin's time, ordinary workers could expect to be promoted to white-collar jobs if they studied and obeyed. This was not the case in Brezhnev's Soviet Union. People holding good jobs held onto them as long as possible. Simply being incompetent wasn't a reason to be fired. In this way, Soviet society under Brezhnev became "static."

Historical Assessments of the Brezhnev Era

Despite Brezhnev's failures in domestic reforms, his foreign policy and defense efforts turned the Soviet Union into a superpower. His popularity among citizens decreased in his last years. Support for communism and Marxism-Leninism weakened. But most Soviet citizens still didn't trust liberal democracy or multi-party systems.

The political corruption that grew during Brezhnev's time became a major problem for the Soviet Union's economy by the 1980s. In response, Andropov started a nationwide anti-corruption campaign. Andropov believed the Soviet economy could recover if the government improved discipline among workers. Brezhnev was seen as vain and self-centered. But he was also praised for bringing an era of stability and calm to the Soviet Union.

After Andropov's death, political struggles led to harsh criticism of Brezhnev and his family. Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, gained support by criticizing Brezhnev's rule. He called it the "Era of Stagnation." Despite these attacks, a 2006 poll showed that 61% of people viewed the Brezhnev era as good for Russia.

Images for kids

-

Leonid Brezhnev speaking at 18th Komsomol Congress opening (25 April 1978)

-

Alexei Kosygin, a member of the collective leadership, with Lyndon B. Johnson, President of the United States, at the 1967 Glassboro Summit Conference.

-

Dmitriy Ustinov, Minister of Defense from 1976 to 1984, managed Soviet national security policy alongside Andrei Gromyko and Yuri Andropov during the final years of Brezhnev's rule.

-

Mikhail Gorbachev, as seen in 1985. He was one of the few younger members elected to top positions during the Brezhnev Era.

-

Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin (front) next to U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson (back) at the Glassboro Summit Conference.

-

Andrei Gromyko, the Soviet Foreign Minister from 1957 to 1985, as seen in 1978 during a visit to the United States.

-

Carter and Brezhnev sign the SALT II treaty on June 18, 1979, in Vienna.

-

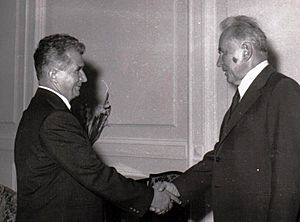

Władysław Gomułka (left), the leader of Poland, in East Germany with Brezhnev.

-

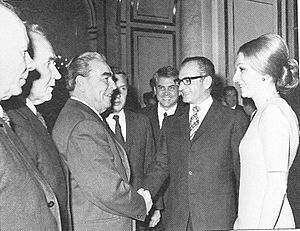

Alexei Kosygin (right) shaking hands with Romanian communist leader Nicolae Ceauşescu on August 22, 1974. Ceauşescu opposed the 1968 Brezhnev Doctrine.

-

Kosygin (left) and Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr (right) signing the Iraqi–Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Co-operation in 1972.

-

Iranian Emperor Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Empress Farah Pahlavi meeting with Brezhnev in Moscow, 1970.

-

May Day parade in Moscow. Participants carry the portrait of Mikhail Suslov – chief ideologist of the Soviet Union.

-

The official reason for removing Nikolai Podgorny, the head of state from 1965 to 1977, was his stance against détente and increasing the supply of consumer goods.

-

Private Nikolai Zaitsev being unanimously inducted into the Komsomol during a border guards' military drill in the Soviet Far East (photo taken in 1969).

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la Unión Soviética (1964–1982) para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la Unión Soviética (1964–1982) para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |