Charles Lindbergh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Lindbergh

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait c. 1927

|

|

| Born |

Charles Augustus Lindbergh

February 4, 1902 Detroit, Michigan, U.S.

|

| Died | August 26, 1974 (aged 72) Kipahulu, Hawaii, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Palapala Ho'omau Church, Kipahulu |

| Other names |

|

| Education | University of Wisconsin–Madison (no degree) |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | First solo transatlantic flight (1927), pioneer of international commercial aviation and air mail |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 13, including Charles Jr., Jon, Anne, and Reeve |

| Parents |

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1924–1941, 1954–1974 |

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was a famous American pilot, military officer, and writer. He became world-renowned on May 20–21, 1927. On these dates, he completed the first nonstop solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. He flew from New York to Paris, covering about 5,800 kilometers (3,600 miles). This incredible journey took him over 33 hours, flying all by himself.

His special airplane, named the Spirit of St. Louis, was built for this challenge. It aimed to win the $25,000 Orteig Prize for the first flight between these two major cities. While others had flown across the Atlantic before, Lindbergh's flight was the first time someone did it alone. It was also the longest flight at that time, setting a new world record for distance. This amazing achievement made Lindbergh a global hero. It also marked the start of a new age for air travel around the world.

Charles Lindbergh grew up mainly in Little Falls, Minnesota, and Washington, D.C.. His father, Charles August Lindbergh, was a U.S. congressman. In 1924, Charles joined the United States Army Air Service as a cadet. The following year, he became a pilot for U.S. Air Mail in the St. Louis area. It was there that he started planning his historic Atlantic crossing.

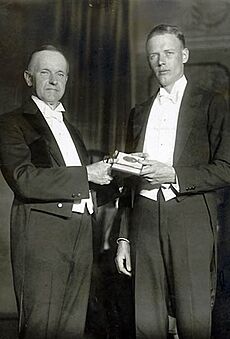

After his successful 1927 flight, President Calvin Coolidge honored him with the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Medal of Honor. These are among the highest U.S. military awards. He was also promoted to colonel in the U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve. France also recognized his bravery with their top award, the Legion of Honor. Lindbergh's flight sparked huge interest in flying lessons, commercial flights, and air mail services. This led to a worldwide "Lindbergh Boom" in aviation. He dedicated much of his time to promoting these new industries.

Time magazine chose Lindbergh as its very first "Man of the Year" in 1927. President Herbert Hoover later appointed him to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics in 1929. In 1930, he received the Congressional Gold Medal. Lindbergh also worked with French surgeon Alexis Carrel in 1931. Together, they helped invent an early perfusion pump. This device was important for making future heart surgeries and organ transplantation possible.

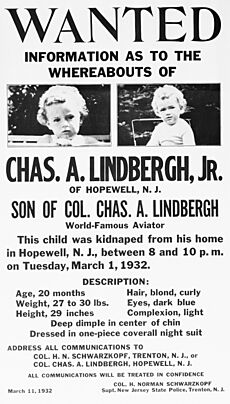

In 1932, a very sad event occurred when Lindbergh's young son, Charles Jr., was taken from their home. This event was widely reported and led to new laws in the U.S. to make kidnapping a serious federal crime. The intense public attention surrounding this case caused the Lindbergh family to move to Europe in 1935, returning in 1939.

Before the United States joined World War II, Lindbergh held strong beliefs about America staying out of the conflict. His views and some of his statements caused controversy. Many people wondered if he supported Nazi Germany. Lindbergh stated he did not support the Nazis and spoke against them at times. However, he did meet with German officials in the 1930s. He also supported the America First Committee, which wanted the U.S. to remain neutral. Due to disagreements with President Franklin Roosevelt about his views, Lindbergh resigned from the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1941. He believed America should not get involved in the war in Europe.

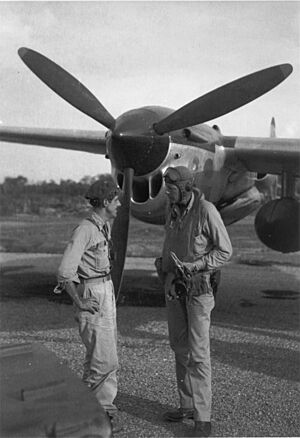

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany declared war on the U.S., Lindbergh strongly supported America's war efforts. However, President Roosevelt did not allow him to return to active military duty. Instead, Lindbergh served as a civilian consultant in the Pacific Theater. He flew 50 combat missions and was even credited with shooting down an enemy plane.

In 1954, President Dwight Eisenhower reinstated Lindbergh's military rank. He also promoted him to brigadier general in the U.S. Air Force Reserve. Later in life, Lindbergh became a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and an explorer. He also became a dedicated environmentalist. He helped create national parks in the U.S. and worked to protect endangered species and native communities. He focused these efforts in places like the Philippines and East Africa. Lindbergh passed away in 1974 in Maui at age 72, after battling lymphoma.

Contents

Early Life and Aviation Dreams

Growing Up and Discovering Flight

Charles Lindbergh was born in Detroit, Michigan, on February 4, 1902. He spent his childhood years in Little Falls, Minnesota, and Washington, D.C.. His father, Charles August Lindbergh, was a U.S. congressman. His mother, Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh, was a chemistry teacher. Charles was their only child together, though he had three older half-sisters. His parents separated when he was seven.

Lindbergh's father served in the U.S. Congress from 1907 to 1917. He was one of the few who did not want the U.S. to enter World War I. Charles graduated from Little Falls High School in 1918. He attended many different schools across the country during his youth. In 1920, he started studying mechanical engineering at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. However, he left college during his second year.

From a young age, Lindbergh loved how motorized machines worked. He was fascinated by cars and motorbikes. Even before college, he became very interested in flying. He had never even touched an airplane up close. In February 1922, he left college and joined a flying school in Lincoln, Nebraska. On April 9, he took his first flight as a passenger.

A few days later, Lindbergh began his formal flying lessons. He couldn't afford to fly solo yet. To gain experience and earn money, he spent months barnstorming. He traveled across several states as a wing walker and parachutist. He also worked briefly as an airplane mechanic.

Lindbergh made his first solo flight in May 1923 in Americus, Georgia. He bought a surplus World War I Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny" biplane for $500. After a short lesson, he flew the Jenny by himself. He then spent much of 1923 barnstorming as "Daredevil Lindbergh." He flew his own plane as the pilot. He even made his first night flight near Lake Village, Arkansas.

In March 1924, Lindbergh began military flight training with the United States Army Air Service. This training lasted a year. He had a serious accident in March 1925 when his plane collided with another mid-air. He had to bail out using a parachute. Only 18 out of 104 cadets finished the training. Lindbergh graduated first in his class in March 1925. He earned his Army pilot's wings and became a second lieutenant.

Lindbergh believed this year was vital for his growth as a pilot and a focused person. The Army didn't need more active pilots at the time. So, he returned to civilian aviation as a barnstormer and flight instructor. He also flew part-time with the Missouri National Guard. He was promoted to first lieutenant in December 1925 and to captain in July 1926.

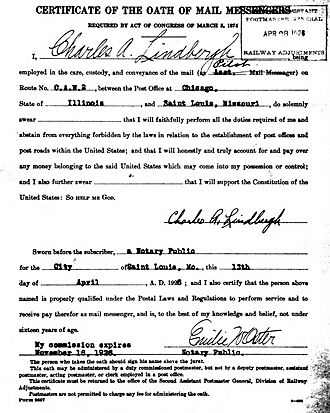

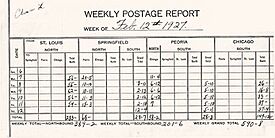

Flying the Mail

In October 1925, Lindbergh was hired by the Robertson Aircraft Corporation (RAC). He became the chief pilot for a new Contract Air Mail route. This route, CAM-2, connected St. Louis and Chicago. It also had stops in Springfield and Peoria, Illinois. Lindbergh and three other pilots flew mail using modified de Havilland DH-4 planes.

He started service on the new route on April 15, 1926. Twice, bad weather or engine problems forced him to parachute out of his plane at night. Both times, he landed safely without serious injury. In early 1927, Lindbergh went to San Diego, California. There, he oversaw the design and building of the Spirit of St. Louis.

The Historic New York to Paris Flight

The Orteig Prize Challenge

In 1919, British pilots John Alcock and Arthur Brown won a prize for the first nonstop transatlantic flight. They flew from Newfoundland to Ireland. Around the same time, a New York hotel owner, Raymond Orteig, offered a $25,000 prize. This award was for the first successful nonstop flight between New York City and Paris.

Several experienced pilots tried to win the Orteig Prize. However, none were successful. In September 1926, French pilot René Fonck's plane crashed during takeoff in New York. Two crew members died. This event inspired Lindbergh to attempt the flight himself. He believed it would be less risky than his mail pilot job. He began gathering support and resources from St. Louis businessmen.

The Spirit of St. Louis Airplane

Finding money for the flight was hard because Lindbergh wasn't famous yet. Two St. Louis businessmen helped him get a $15,000 bank loan. Lindbergh added $2,000 of his own savings. Another $1,000 came from the RAC. His total of $18,000 was much less than what his rivals had.

Lindbergh's team tried to buy a plane from several manufacturers. But they all wanted to choose the pilot. Finally, the Ryan Airline Company in San Diego agreed to build a custom plane. It cost $10,580. The deal was finalized on February 25, 1927. The plane was named the Spirit of St. Louis. It was a single-seat, single-engine monoplane. Lindbergh and Ryan's chief engineer, Donald A. Hall, designed it together.

The Spirit flew for the first time just two months later. After several test flights, Lindbergh took off from San Diego on May 10. He flew first to St. Louis, then to Roosevelt Field in New York.

The Epic Flight Across the Atlantic

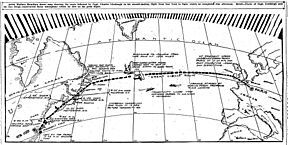

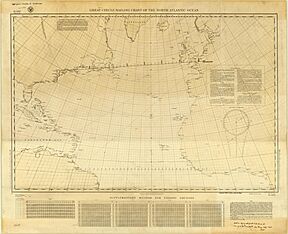

In the early morning of Friday, May 20, 1927, Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island. His goal was Le Bourget Aerodrome, near Paris. This was about 5,800 kilometers (3,610 miles) away. Lindbergh had barely slept the night before. It was raining that morning, but the rain stopped as his plane was moved to the runway. A crowd of thousands gathered to see him off.

The Spirit was loaded with 450 gallons of fuel. This was a thousand pounds heavier than any test flight. The fully loaded plane weighed 5,200 pounds (2,359 kg). The muddy runway made takeoff difficult. Men pushed the wing struts to help the plane gain speed. The Spirit slowly picked up speed. It cleared the telephone lines at the end of the field by about 20 feet (6 meters).

An hour after takeoff, Lindbergh was flying over Rhode Island. He passed Boston and Cape Cod. He started to feel tired, even though it was still early. To stay awake, he flew very low, just 10 feet (3 meters) above the water. He later climbed to 200 feet (61 meters). By then, he was 400 miles (644 km) from New York.

He saw Nova Scotia and flew over the Gulf of Maine. He was only slightly off course. By late afternoon, he was over Cape Breton Island. He struggled to stay awake. At 7:15 PM, he passed St. John's. The New York Times reported his sighting, noting he was heading for Ireland.

As night fell, stars appeared. Fog covered the sea, so Lindbergh climbed higher. He flew from 800 feet (244 meters) to 7,500 feet (2,286 meters) to stay above the clouds. He encountered a large thunderhead cloud. Ice began to form on the plane, so he turned back to clear sky. He felt the ice particles with his bare hand. Later, he flew into warmer air, and the ice melted. He was 500 miles (805 km) from Newfoundland.

Eighteen hours into the flight, he was halfway to Paris. He felt dread instead of celebration. Dawn came early due to time zones. He started to hallucinate and fell asleep repeatedly for short moments. Eventually, the weather cleared. After 24 hours in the air, he felt less tired.

Around 27 hours after leaving New York, Lindbergh saw porpoises and fishing boats. This was a sign he had reached Europe. He circled a boat, seeing a face watching from a porthole. Dingle Bay in southwest Ireland was his first European landfall. He was only 3 miles (5 km) off course. He increased his speed to reach the French coast in daylight. He flew over the English coast and then Cherbourg, France.

During the 33 and a half hours of flight, Lindbergh battled ice and flew through fog. He navigated using only dead reckoning. He didn't use radio navigation because it was heavy and unreliable. Luckily, the winds over the Atlantic balanced out, helping him stay on course.

Upon reaching Paris, Lindbergh circled the Eiffel Tower. He then flew to Le Bourget Aerodrome. He landed at 10:22 PM on Saturday, May 21. The airfield was not on his map. He mistook the bright lights for an industrial complex. These lights were actually from tens of thousands of spectators' cars. They caused the biggest traffic jam in Paris history.

An estimated 150,000 people stormed the field. They pulled Lindbergh from his cockpit and carried him above their heads. Souvenir hunters caused minor damage to the Spirit. French military and police helped move the pilot and plane to a hangar. The New York Times reported that spectators stripped the plane of anything they could take. Soldiers with bayonets guarded the plane as it was moved.

Lindbergh met the U.S. Ambassador to France, Myron T. Herrick. He gave him letters he carried across the Atlantic. Lindbergh left the airfield around midnight. He was driven through Paris, stopping at the French Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. He finally slept at the ambassador's residence, after about 60 hours awake.

Global Recognition and Tours

Lindbergh received huge praise after his flight. People acted as if he had done something truly miraculous. The New York Times ran a huge headline: "Lindbergh Does It!" His mother's house was surrounded by nearly a thousand people. He became an international celebrity. Invitations poured in from European countries. He received marriage proposals, gifts, and thousands of letters. Over 200 songs were written about him.

The morning after landing, Lindbergh appeared on the balcony of the U.S. embassy. He spoke briefly and modestly to the crowd. The French Foreign Office flew the American flag, a rare honor for someone not a head of state. At the Élysée Palace, French President Gaston Doumergue awarded him the Légion d'honneur.

Lindbergh flew the Spirit to Belgium and Britain before returning to the U.S. In Brussels, he was greeted by a million people. Belgian Prime Minister Henri Jaspar welcomed him. King Albert I made Lindbergh a Knight of the Order of Leopold.

In Britain, 100,000 people mobbed him at Croydon Air Field. Police struggled to control the crowd. Lindbergh told them, "All I can say is that this is worse than what happened at Le Bourget Field." He asked them to "Save my plane!" The Spirit was moved to a hangar under military guard.

On May 31, Lindbergh met British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin. He then visited Buckingham Palace. King George V awarded him the British Air Force Cross. On June 11, 1927, he returned to the United States aboard the USS Memphis. President Calvin Coolidge awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross.

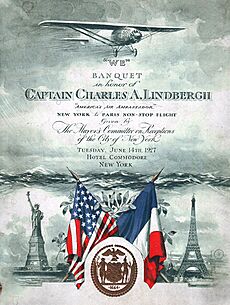

On June 13, Lindbergh flew to New York City. He was honored with a huge ticker-tape parade up the Canyon of Heroes. Mayor Jimmy Walker received him at City Hall. He was given the New York Medal for Valor in Central Park. About 4,000,000 people saw him that day.

On July 18, 1927, Lindbergh was promoted to colonel in the U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve. On December 14, 1927, a special Act of Congress awarded him the Medal of Honor. This was usually given for combat heroism. President Coolidge presented it to him on March 21, 1928.

Lindbergh was the first Time magazine Man of the Year in 1927. He was 25, the youngest until 2019. Elinor Smith Sullivan, a famous aviator, said Lindbergh's flight changed aviation forever. "After Lindbergh, suddenly everyone wanted to fly," she said.

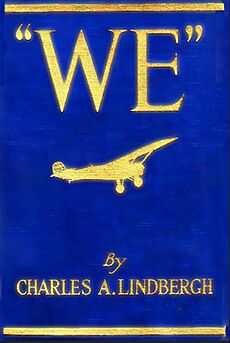

Autobiography and Promoting Aviation

Two months after his Paris flight, Lindbergh published his autobiography, "WE". It was the first of 15 books he wrote or helped write. The book sold over 650,000 copies in its first year. It earned Lindbergh more than $250,000.

This success was boosted by his three-month tour of the United States. He flew the Spirit 22,350 miles (36,000 km). Between July and October 1927, he visited 82 cities in all 48 states. He rode in parades and gave 147 speeches to 30 million people.

Lindbergh then toured 16 Latin American countries. This "Good Will Tour" covered 9,390 miles (15,112 km). He met his future wife, Anne Morrow, in Mexico. A year after its first flight, Lindbergh flew the Spirit to Washington, D.C. It has been on display at the Smithsonian Institution ever since.

His flight sparked a "Lindbergh Boom" in aviation. Air mail volume increased by 50 percent. Applications for pilot licenses tripled, and the number of planes quadrupled. President Herbert Hoover appointed Lindbergh to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.

In 1931, Lindbergh and his wife flew from Long Island to Siberia, Japan, and China. They used a Lockheed Model 8 Sirius plane named Tingmissartoq. This trip helped explore air routes for future commercial service. In China, they helped with disaster relief during a major flood.

Promoting Air Mail Service

Lindbergh used his fame to promote air mail. In February 1928, he carried special souvenir mail. He flew it between Santo Domingo, Port-au-Prince, and Havana. These were the last stops on his "Good Will Tour."

He also flew special flights over his old CAM-2 route in February 1928. Tens of thousands of souvenir covers were sent to him. At each stop, he switched planes. This ensured each cover was flown by him. The covers were then returned to their senders. This promoted the air mail service.

From 1929 to 1931, Lindbergh carried smaller numbers of souvenir covers. These were on first flights over new routes in Latin America and the Caribbean. He had helped plan these routes as a consultant for Pan American World Airways.

On March 10, 1929, Lindbergh flew an inaugural flight from Brownsville, Texas, to Mexico City. He carried U.S. mail in a Ford Trimotor airplane. This flight marked the start of extended airmail service between the U.S. and Mexico.

Personal Life and Challenges

His American Family

Lindbergh believed in stable, long-term relationships. He valued intellect, good health, and strong genes. He felt his experience with farm animals taught him about heredity.

He met Anne Morrow in Mexico City in December 1927. Anne was the daughter of Dwight Morrow. Morrow was a partner at J.P. Morgan & Co. and the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico. They married on May 27, 1929, in Englewood, New Jersey.

They had six children: Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. (1930–1932), Jon Morrow Lindbergh (1932–2021), Land Morrow Lindbergh (b. 1937), Anne Lindbergh (1940–1993), Scott Lindbergh (b. 1942), and Reeve Lindbergh (b. 1945). Lindbergh taught Anne to fly. She often joined him on his explorations and charting of air routes.

On the evening of March 1, 1932, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., who was 20 months old, was kidnapped. This happened at the Lindberghs' home in East Amwell, New Jersey. A man claiming to be the kidnapper collected a $50,000 ransom on April 2. The serial numbers of the bills were recorded. On May 12, the Charles's remains were found.

This case was called the "Crime of the Century" by the media. In response, Congress passed the ""Lindbergh Law"." This law made kidnapping a federal crime if the victim is taken across state lines. It also applied if the kidnapper used mail or interstate commerce for ransom demands.

Richard Hauptmann, a 34-year-old German immigrant, was arrested in New York in September 1934. He was caught after paying for gasoline with one of the ransom bills. Police found $13,760 of the ransom money and other evidence in his home. Hauptmann was tried for kidnapping and murder in January 1935. He was convicted and sentenced to death. He was executed in April 1936.

Living in Europe (1936–1939)

Lindbergh was a very private person. The intense public attention after the kidnapping and trial was overwhelming. He worried about the safety of his second son, Jon. In December 1935, the family secretly sailed from Manhattan to Liverpool. They traveled under false names with diplomatic passports.

News of their move to Europe became public a day later. They arrived in Liverpool on December 31 and then went to South Wales. The family eventually rented "Long Barn" in Kent, England. In 1938, they moved to Île Illiec, a small island off the French coast.

The Lindberghs lived and traveled extensively around Europe. They used their personal Miles M.12 Mohawk airplane. They returned to the U.S. in April 1939. General H. H. ("Hap") Arnold asked Lindbergh to help evaluate the Air Corps' readiness for war. Lindbergh's duties included testing new aircraft and finding sites for air bases. He toured facilities in a Curtiss P-36 fighter. This was his first active military service since 1925.

Scientific Contributions

Lindbergh wrote to the Longines watch company. He described a watch design to help pilots with navigation. The "Lindbergh Hour Angle watch" was first made in 1931. It is still produced today.

In 1929, Lindbergh became interested in rocket pioneer Robert H. Goddard's work. Lindbergh helped Goddard get funding from Daniel Guggenheim in 1930. This allowed Goddard to expand his research. Lindbergh remained a strong supporter of Goddard's work throughout his life.

In 1930, Lindbergh's sister-in-law developed a serious heart condition. This made Lindbergh wonder if hearts could be repaired with surgery. Starting in 1931, he studied organ perfusion outside the body. He worked with Nobel Prize-winning French surgeon Alexis Carrel.

Lindbergh invented a glass perfusion pump, called the "Model T" pump. This invention helped make future heart surgeries possible. In 1938, Lindbergh and Carrel described an artificial heart in their book, The Culture of Organs. It took decades for a working artificial heart to be built. Others later developed Lindbergh's pump. This eventually led to the creation of the first heart-lung machine.

Pre-War Views and World War II Service

Controversial Pre-War Activities

In July 1936, Lindbergh visited Berlin before the 1936 Summer Olympics. He made several visits to Germany between 1936 and 1938. These trips were at the request of the U.S. military. His goal was to evaluate German aviation. He was impressed by German technology and their air force.

During these visits, German officials, including Hermann Göring, hosted Lindbergh. In 1938, Göring presented Lindbergh with the Commander Cross of the Order of the German Eagle. Lindbergh's acceptance of this medal became controversial. This was especially true after the Kristallnacht, an anti-Jewish event by the Nazi Party. Lindbergh chose not to return the medal. He believed it was given in peace and returning it would be an unnecessary insult.

Lindbergh's private thoughts on the Kristallnacht were recorded in his diary. He wrote that he didn't understand the riots. He found them contrary to German order and intelligence. He acknowledged a "Jewish problem" but questioned the unreasonable handling of it.

Lindbergh had planned to move to Berlin in 1938–39. He found a house, but Nazi friends advised against it because it was previously owned by Jews. He canceled the trip on the advice of his friend Alexis Carrel.

Isolationism and America First

In 1938, Lindbergh inspected Nazi Germany's Air Force. He was impressed by their strength. He believed the U.S. should not get involved in the upcoming European conflict. He thought France was militarily weak and Britain relied too much on its navy. He suggested they strengthen their air power. This would force Hitler to focus on "Asiatic Communism".

After Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia and Poland, Lindbergh opposed sending aid to threatened countries. He argued that helping one side would lead America into war. He believed America should not profit from war and destruction.

In August 1939, Lindbergh was considered by Albert Einstein to deliver a letter to President Roosevelt. The letter warned about the potential of nuclear fission. However, Lindbergh did not respond. Two days later, Lindbergh gave a radio address. He called for isolationism and suggested that certain groups were pushing the country toward war.

In October 1939, Lindbergh criticized Canada for joining the European war. He believed the Americas should be free from European powers. In November 1939, he wrote an article for Reader's Digest. He argued for peace among Western nations. He also suggested a German focus on the Soviet Union.

In late 1940, Lindbergh became a spokesman for the America First Committee. This group wanted the U.S. to stay out of World War II. He spoke to large crowds, arguing America should not attack Germany. He believed destroying Hitler would leave Europe open to Soviet influence.

In April 1941, he spoke to 30,000 members of the America First Committee. He claimed the British government wanted America to send troops to Europe. He believed this would lead to a shared "fiasco" of war.

Lindbergh proposed that the U.S. negotiate a neutrality pact with Germany. President Franklin Roosevelt publicly called Lindbergh's views "defeatist." Lindbergh resigned his colonel's commission in the U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve. He felt he had "no honorable alternative" after Roosevelt questioned his loyalty.

On September 11, 1941, Lindbergh gave a speech in Des Moines. He accused three groups of pushing the U.S. toward war: the British, the Jewish people, and the Roosevelt Administration. He suggested that Jewish Americans had too much control over government and media. This speech caused a strong public backlash. Newspapers, politicians, and clergy criticized his remarks.

Views on Race and Society

Lindbergh's speeches and writings showed his views on race and society. These views were similar to some ideas of the German Nazis. He was suspected of being a Nazi sympathizer. However, in a September 1941 speech, Lindbergh stated, "no person with a sense of the dignity of mankind can condone the persecution of the Jewish race in Germany."

President Roosevelt strongly disliked Lindbergh's opposition to his policies. He believed Lindbergh was pro-Nazi. After the war, Lindbergh visited a Nazi concentration camp. He wrote in his diary about the extreme degradation he witnessed. He questioned how national progress could justify such a place.

In a 1939 speech, Lindbergh said, "Our bond with Europe is a bond of race and not of political ideology." He believed the "European race" must be preserved. He thought that if the white race was threatened, they should fight together. He did not want them fighting against each other.

Lindbergh developed a friendship with automobile pioneer Henry Ford. Lindbergh considered Russia a "semi-Asiatic" country compared to Germany. He believed Communism would destroy Western "racial strength." He preferred an alliance with Nazi Germany over Soviet Russia. He admired the "German genius for science," "English genius for government," and "French genius for living." He thought these could blend in America to form a "greatest genius of all."

Holocaust researcher Max Wallace agreed with Roosevelt that Lindbergh was "pro-Nazi." However, he found no evidence of disloyalty or treason. Wallace saw Lindbergh as well-meaning but misguided. His leadership of the isolationist movement negatively impacted Jewish people.

Lindbergh's biographer, A. Scott Berg, suggested Lindbergh was stubborn in his beliefs. He was also inexperienced in politics. This made it easy for rivals to portray him as a Nazi supporter. Lindbergh's views were common in the U.S. during the period between the world wars. His support for the America First Committee reflected many Americans' feelings.

Lindbergh believed the main conflict would be between the Soviet Union and Germany. He did not see it as a battle between fascism and democracy. He always championed military strength for defense. He thought a strong military would make America an impenetrable fortress. This would defend the Western Hemisphere from foreign attacks.

The attack on Pearl Harbor shocked Lindbergh. However, he had predicted that America's policy in the Philippines could lead to war. He warned that the islands should either be fortified or abandoned.

World War II Combat Missions

In January 1942, Lindbergh sought to rejoin the Army Air Forces. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson opposed this due to Lindbergh's public comments. Blocked from active military service, Lindbergh offered his services as a consultant to aviation companies. In 1942, he worked with Ford. He helped solve problems on the Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber production line at Willow Run.

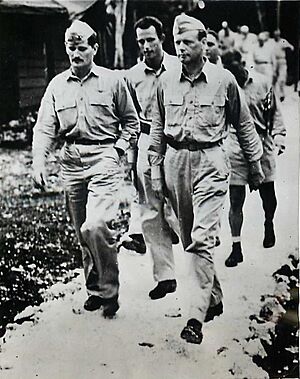

In 1943, he joined United Aircraft as an engineering consultant. He focused on their Chance-Vought Division. In 1944, United Aircraft sent him to the Pacific Theater. His role was to study aircraft performance in combat. He bought a naval officer's uniform without insignia. He also bought a New Testament, his chosen book for the trip.

Lindbergh showed United States Marine Corps Aviation pilots how to take off safely. They could carry a bomb load double the Vought F4U Corsair's rated capacity. On May 21, 1944, Lindbergh flew his first combat mission. It was a strafing run near the Japanese garrison of Rabaul. He also flew with other Marine squadrons.

In his six months in the Pacific, Lindbergh flew 50 combat missions as a civilian. His ideas for using Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters impressed General Douglas MacArthur. Lindbergh taught P-38 pilots engine-leaning techniques. This greatly improved fuel consumption. It allowed the planes to fly longer missions. Pilots who served with Lindbergh praised his courage and patriotism.

On July 28, 1944, Lindbergh shot down a Japanese observation plane. This happened during a P-38 bomber escort mission. His combat participation was revealed in a newspaper story in October 1944.

Later Life and Environmentalism

After World War II, Lindbergh lived in Darien, Connecticut. He worked as a consultant for the U.S. Air Force and Pan American World Airways. He remained concerned about Soviet power. He noted that freedom was suppressed in many parts of the world. He believed America had not achieved its war objectives.

Lindbergh felt that "a whole civilization is in disintegration." He thought America needed to support Europe against communism. He believed the U.S. had a responsibility to help Europe after the war. He also firmly supported the Nuremberg trials for war crimes.

In June 1945, Lindbergh toured Germany. He visited the Dora concentration camp. He inspected the tunnels and saw V-1 and V-2 missile parts. He tried to understand how such technology was used for evil. He wrote that it seemed impossible for civilized men to degenerate to such a level. He also noted the mistreatment of Japanese people by Americans during the war.

Lindbergh returned from Europe alarmed about the world's state. He realized the public no longer cared for his opinions. He concluded that lasting peace must be based on "Christian principles, on justice, on compassion." He believed in a "sense of the dignity of man."

Lindbergh became more spiritual in his later years. He grew concerned about technology's impact on the world. In 1948, he published Of Flight and Life. This book warned against the dangers of scientific materialism. He wrote about his conversion from worshipping science to worshipping God's eternal truths.

In 1949, he received the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy. In his speech, he said, "we must measure scientific accomplishments by their effect on man himself." On April 7, 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower commissioned Lindbergh as a brigadier general in the U.S. Air Force Reserve. He also won the Pulitzer Prize in 1954 for his book, The Spirit of St. Louis.

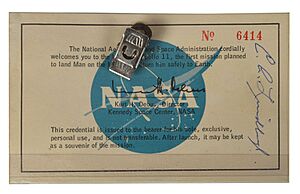

In December 1968, he visited the astronauts of Apollo 8. In July 1969, he and his wife watched the launch of Apollo 11. They were personal guests of Neil Armstrong. Lindbergh shared his thoughts on the lunar landing during live television coverage. He later wrote the foreword to astronaut Michael Collins's autobiography.

Protecting Nature and Indigenous Cultures

In his later life, Lindbergh became deeply involved in conservation movements. He worried about technology's negative effects on nature and native peoples. He focused on regions like Hawaii, Africa, and the Philippines. He campaigned to protect endangered species such as the humpback whale and Philippine eagle. He also helped establish protections for the Tasaday and Agta people. He worked with African tribes like the Maasai.

With Laurance S. Rockefeller, Lindbergh helped establish the Haleakalā National Park in Hawaii. He also worked to protect Arctic wolves in Alaska. He helped create Voyageurs National Park in northern Minnesota.

In a 1964 Reader's Digest essay, Lindbergh wrote about a realization in Kenya. He compared building an airplane to the "evolutionary achievement of a bird." He concluded, "if I had to choose, I would rather have birds than airplanes." He questioned his old definition of "progress." He believed nature showed more true progress than human creations. His essays introduced millions to the conservation cause. He urged people to live lives less complicated by technology.

On May 14, 1971, Lindbergh received the Philippine Order of the Golden Heart. He was honored as an aviation pioneer who now protected nature from technology. He actively worked to protect species like the tamaraw and Philippine eagle. He lent his name to a law against killing the eagle.

1972 Philippines Expedition

In 1972, Lindbergh went on an expedition to Mindanao, Philippines. He investigated reports of a lost tribe, the Tasaday. He worked with Philippine politician Manuel Elizalde Jr. to preserve Tasaday land.

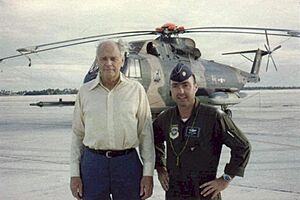

During his expedition, the support helicopter had mechanical trouble. Lindbergh's party sent a radio message for help. The U.S. Air Force's 31st Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron rescued them. Major Bruce Ware and his crew flew over 600 miles (966 km). They extracted all 46 stranded individuals. Lindbergh commented that he had helped develop in-flight refueling, but had never been rescued by a helicopter during the process.

Major Ware received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions. The other crew members received the Air Medal. Ware noted that his medal was awarded quickly due to Lindbergh's international hero status.

Retirement in Hawaii

Lindbergh spent his last years in Kipahulu, Maui. He built a small, rustic cottage there in 1971. He joined efforts with Samuel F. Pryor Jr. to preserve plants and wildlife in Kipahulu Valley. His choice of Maui reflected his love for natural places and simplicity.

Richard Hallion wrote that Lindbergh recognized society's fragile state in the nuclear era. He feared humanity could destroy in minutes what took centuries to create. Lindbergh transformed from a technologist to a philosopher. He advocated for a shift from materialism to a society based on "simplicity, humiliation, contemplation, prayer." Susan M. Gray wrote that Lindbergh found a "middle ground" between technology and human values. He embraced both and rejected neither.

Death and Legacy

In 1972, Lindbergh became sick with lymphoma. He passed away on August 26, 1974, at age 72. After his cancer diagnosis, he designed his grave and coffin. He wanted a traditional Hawaiian style. He spent several months recuperating in Maui after radiation treatments.

He decided to leave the hospital in New York when treatment didn't help. He returned to Kipahulu with his wife, Anne. He died a week later. He was buried at Palapala Ho'omau Church in Kipahulu, Maui. This church was restored by his friend Samuel F. Pryor Jr. and the Lindbergh family.

President Gerald Ford paid tribute to Lindbergh. He said Lindbergh's courage would never be forgotten. He described him as a selfless, sincere man. For a generation, the "Lone Eagle" represented the best of America.

Honors and Tributes

- Lindbergh received the Silver Buffalo Award from the Boy Scouts of America on April 10, 1928.

- On May 8, 1928, a statue was dedicated at Paris–Le Bourget Airport honoring Lindbergh. It also honored Charles Nungesser and François Coli, who disappeared attempting the same flight.

- San Diego International Airport was named Lindbergh Field from 1928 to 2003. A replica of his plane hangs there.

- Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport Terminal 1 is named Lindbergh.

- In 1933, the Lindbergh Range in Greenland was named after him.

- In St. Louis County, Missouri, a school district, high school, and highway are named for Lindbergh. He has a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

- He was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1967.

- The Royal Air Force Museum minted a medal with his image in 1972.

- His childhood home in Little Falls, Minnesota, is a museum and a National Historic Landmark.

- In 2002, the Medical University of South Carolina established the Lindbergh-Carrel Prize. It honors contributors to organ preservation and growth.

Awards and Decorations

Lindbergh received many awards and medals. Most were donated to the Missouri Historical Society. They are displayed at the Jefferson Memorial, part of the Missouri History Museum.

United States Government

Medal of Honor (December 14, 1927)

Medal of Honor (December 14, 1927) Distinguished Flying Cross (June 11, 1927)

Distinguished Flying Cross (June 11, 1927)- Langley Gold Medal from the Smithsonian Institution (1927)

- Congressional Gold Medal (Presented August 15, 1930)

Other U.S. Awards

- Orteig Prize (1927)

- Harmon Trophy (1927)

- Hubbard Medal (1927)

- Honorary Scout (Boy Scouts of America, 1927)

- New York State Medal for Valor (June 13, 1927)

- Silver Buffalo Award (Boy Scouts of America, 1928)

- Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy (1949)

- Daniel Guggenheim Medal (1953)

- Pulitzer Prize (1954)

Non-U.S. Awards

Commander of the Legion of Honor (France, 1927, promoted 1930)

Commander of the Legion of Honor (France, 1927, promoted 1930) Knight of the Order of Leopold (Belgium, May 28, 1927)

Knight of the Order of Leopold (Belgium, May 28, 1927) Air Force Cross (United Kingdom, May 31, 1927)

Air Force Cross (United Kingdom, May 31, 1927) Silver Cross of Boyacá (Colombia, January 28, 1928)

Silver Cross of Boyacá (Colombia, January 28, 1928) Order of the Liberator, Commander (Venezuela, January 29, 1928)

Order of the Liberator, Commander (Venezuela, January 29, 1928) Order of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, Grand Cross (Cuba, February 10, 1928)

Order of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, Grand Cross (Cuba, February 10, 1928) Order of the Rising Sun, Third Class (Japan, September 9, 1931)

Order of the Rising Sun, Third Class (Japan, September 9, 1931) Aeronautical Virtue Order (Romania, January 13, 1933)

Aeronautical Virtue Order (Romania, January 13, 1933) Order of the German Eagle with Star (Nazi Germany, October 19, 1938)

Order of the German Eagle with Star (Nazi Germany, October 19, 1938)- Gold Medal "Plus Ultra" (Spain, June 1, 1927)

- Order of the Golden Heart (Philippines, May 14, 1971)

- Fédération Aéronautique Internationale FAI Gold Medal (1927)

- ICAO Edward Warner Award (1975)

- Royal Swedish Aero Clubs Gold plaque (1927)

Medal of Honor Citation

Rank and organization: Captain, U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve. Place and date: From New York City to Paris, France, May 20–21, 1927. Entered service at: Little Falls, Minn. Born: February 4, 1902, Detroit, Mich. G.O. No.: 5, W.D., 1928; Act of Congress December 14, 1927.

Citation

For displaying heroic courage and skill as a navigator, at the risk of his life, by his nonstop flight in his airplane, the "Spirit of St. Louis", from New York City to Paris, France, 20–21 May 1927, by which Capt. Lindbergh not only achieved the greatest individual triumph of any American citizen but demonstrated that travel across the ocean by aircraft was possible.

Other Recognition

- 1934–1939 Trustee of the Carnegie Institution

- 1965 International Aerospace Hall of Fame Inductee

- 1991 Scandinavian-American Hall of Fame Inductee

- Ranked No. 3 on Flying magazine's 51 Heroes of Aviation

- Member of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows

Writings

Besides "WE" and The Spirit of St. Louis, Lindbergh wrote many other books. These covered topics like science, technology, nationalism, war, and values. His other books include: The Culture of Organs (with Dr. Alexis Carrel) (1938), Of Flight and Life (1948), The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh (1970), Boyhood on the Upper Mississippi (1972), and his unfinished Autobiography of Values (published after his death, 1978).

See Also

In Spanish: Charles Lindbergh para niños

In Spanish: Charles Lindbergh para niños