History of Estonia facts for kids

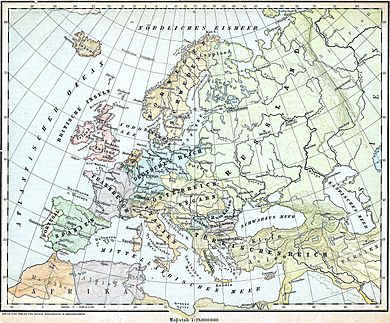

The history of Estonia is a part of history of Europe. People first settled in the area of Estonia around 8500 BC, after the last ice age.

Contents

- Ancient Estonia: Early History

- Estonian Crusade: The Middle Ages Begin

- Danish Estonia: A New Power

- Terra Mariana: A Church State

- Estonia Divided: The Livonian War

- Estonia Under Russian Rule (1710–1917)

- Road to Independence (1917–1920)

- Between Wars (1920–1939)

- World War II (1939–1944)

- Soviet Estonia (1944–1991)

- Restoring Independence

- Estonian Government Today (1992–Present)

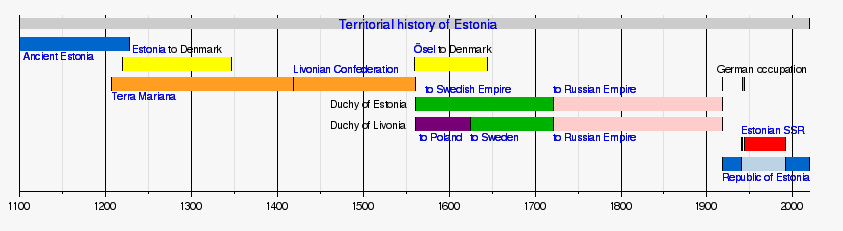

- Time line

- See also

Ancient Estonia: Early History

First People: Mesolithic Period

Humans have lived in Estonia since about 10,000 BC, after the last big ice age ended. The first signs of people are linked to the Kunda culture. The old Mesolithic settlement of Pulli is by the Pärnu River. It dates back to the early 9th millennium BC. The Kunda culture is named after the Lammasmäe site in northern Estonia, from before 8500 BC. Tools like those from Kunda have been found in Latvia, Lithuania, and Finland. People mostly used flint and quartz for cutting tools.

New Ways of Life: Neolithic Period

The Neolithic Period started with the Narva culture's ceramics around 5000 BC. The oldest finds are from about 4900 BC. Early pottery was made from thick clay mixed with pebbles or shells. Narva-style pottery is found all along Estonia's coast and on its islands. The stone and bone tools from this time are similar to those of the Kunda culture.

Around 4000 BC, the Comb Ceramic culture arrived in Estonia. For a long time, people thought this meant the ancestors of Estonians and Finns arrived. But now, experts think more settlements appeared because the climate got warmer. Some even believe an early Uralic language was spoken in Estonia since the last ice age.

The Comb Ceramic people buried their dead with figures of animals and people made from bone and amber. Items from this culture are found from Finland to Prussia.

The Late Neolithic Period began around 2200 BC. This time saw the Corded Ware culture with its special pottery and polished stone axes. We know they started farming because of burnt wheat grains found on a pot. They also tried to tame wild boar.

People were buried on their sides with knees bent. Objects placed in graves were made from bones of farm animals.

Bronze Age: New Materials and Settlements

The Bronze Age in Estonia started around 1800 BC. This was when the borders between the Finnic peoples and the Balts began to form. The first fortified settlements were built, like Asva and Ridala on Saaremaa island, and Iru in northern Estonia. Shipbuilding helped bronze spread. Burial customs changed, with stone cist graves and cremation becoming common.

Around 700 BC, a large meteorite hit Saaremaa island, creating the Kaali craters.

Around 325 BC, the Greek explorer Pytheas might have visited Estonia. Some think the island of Thule he wrote about was Saaremaa.

Iron Age: Tools and Tribes

The Pre-Roman Iron Age in Estonia lasted from about 500 BC to 50 AD. The first iron items were brought in from other places. But from the 1st century, people started making iron from local marsh and lake ore. Settlements were often in naturally protected places. Fortresses were built but used only sometimes.

Square fields surrounded by fences, called Celtic fields, appeared in Estonia during this time. Many stones with man-made indents, likely for magic to help crops grow, also date from this period. A new type of grave, square burial mounds, began to appear. Burial traditions show that society was starting to have different social classes.

The Roman Iron Age in Estonia was from about 50 to 450 AD. This time was influenced by the Roman Empire. We see this in a few Roman coins, jewelry, and other items found. Many iron items in southern Estonia show strong ties with southern areas. Islands in western and northern Estonia traded mainly by sea. By the end of this period, three distinct tribal areas had formed: northern, southern, and western Estonia (including the islands). Each group developed its own identity.

Early Middle Ages: New Names and Leaders

The name "Estonia" first appeared as "Aestii" in the 1st century AD by Tacitus. However, this might have meant Baltic tribes. In Scandinavian sagas (9th century), the term began to mean Estonians.

Ptolemy mentioned the Osilians among people living on the Baltic shore in the 2nd century CE.

The Roman historian Cassiodorus (5th century) said the "Aestii" were Estonians. Their religion was known for "wind-magic." Cassiodorus mentioned Estonia in his book from the 6th century.

The Chudes, mentioned by a monk Nestor in early Kyivan Rus chronicles, were the Estonians.

In the first centuries AD, Estonia started to have political areas. Two larger areas appeared: the parish (kihelkond) and the county (maakond). A parish had several villages and usually a fortress. A parish elder led its defense. A county was made of several parishes, also led by an elder. By the 13th century, major counties included Saaremaa, Läänemaa, Harjumaa, Rävala, Virumaa, Järvamaa, Sakala, and Ugandi.

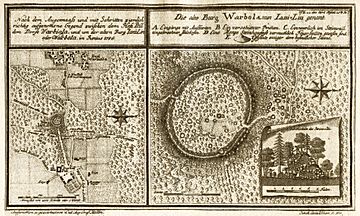

Varbola Stronghold was a large fortress and trade center in Harju County.

In the 11th century, Scandinavians often fought Vikings from the eastern Baltic Sea. With Christianity rising, countries like Scandinavia and Germany started the Baltic crusades. This led to military conquests of the Livs, Letts, Estonians, Prussians, and Finns. They were defeated, baptized, and sometimes killed by Germans, Danes, and Swedes.

Estonian Crusade: The Middle Ages Begin

Estonia was one of the last places in medieval Europe to become Christian. In 1193, Pope Celestine III called for a crusade against pagans in Northern Europe. Crusaders from northern Germany built a base in Riga (modern Latvia). With help from newly Christianized local tribes, crusaders began raids into Estonia in 1208. Estonian tribes fought back fiercely. In 1217, the German crusading order, the Sword Brethren, won a big battle where the Estonian leader Lembitu was killed.

Danish Estonia: A New Power

Northern Estonia was taken over by Danish crusaders led by King Waldemar II. They arrived in 1219 at the site of Lindanisse (now Tallinn). The Danish army defeated the Estonians at the Battle of Lindanise.

Estonians in Harria started a rebellion in 1343, called the St. George's Night Uprising. The Livonian Order then took over the province. In 1346, Denmark sold its lands in Estonia (Harria and Vironia) to the Livonian Order for 10,000 marks.

Swedish Coastal Settlements

The first mention of Estonian Swedes is from 1294. They are one of Estonia's oldest known minority groups. They were also called "Coastal Swedes" or "island people" (aibofolke). Their homeland was called Aiboland.

Swedish settlements were on Ruhnu Island, Hiiumaa Island, the west coast, and smaller islands. They also lived on the northwest coast of the Harju District and Naissaar Island near Tallinn. Towns with many Swedes included Haapsalu and Tallinn.

Terra Mariana: A Church State

In 1227, the Sword Brethren conquered the last Estonian stronghold on Saaremaa island. After this, all remaining pagan Estonians were supposedly Christianized. A church state called Terra Mariana was created. The conquerors controlled the land using many castles.

The land was then divided among the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order, the Bishopric of Dorpat, and the Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek. Northern Estonia was part of Denmark until 1346. Tallinn joined the Hanseatic League in the late 13th century. In 1343, people in northern Estonia and Saaremaa rebelled against their German rulers. This uprising was put down, and four Estonian "kings" were killed.

Despite local rebellions and invasions, the local German-speaking upper class continued to rule Estonia. By the end of the Middle Ages, these Baltic Germans were the ruling class. They were traders in cities and landowners in the countryside.

The Reformation: A New Religion

The Protestant Reformation began in Europe in 1517 with Martin Luther. It reached Estonia in the 1520s. The Reformation in Estonia was supported by local and Swedish leaders. Lutheranism helped more people learn to read. However, peasants were traditional and preferred Catholic ways at first.

After 1600, Swedish Lutheranism became dominant. New churches were built to help people understand and join in services. Pews were added for common people to listen to sermons. Altars often showed the Last Supper, but statues of saints were removed. The Baltic German elite promoted Lutheranism. Church services were now in the local language, not Latin, and the first book was printed in Estonian.

Estonia Divided: The Livonian War

During the Livonian War in 1561, northern Estonia came under Swedish control. Southern Estonia was briefly controlled by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 1580s. By 1625, all of mainland Estonia was under Swedish rule. Estonia was divided into two areas: Estonia in the north and Livonia in southern Estonia and northern Latvia. This division lasted until the early 20th century.

Many countries were involved in the Livonian War, including Sweden, Poland, Denmark, and Russia. The war was long and costly for everyone. Eventually, Sweden gained more control over the region.

In 1631, Gustavus II Adolphus of Sweden made nobles give peasants more freedom. In 1632, he started a printing press and a university in Tartu.

Estonia Under Russian Rule (1710–1917)

Sweden lost to Russia in the Great Northern War. This led to Estonia and Livonia surrendering in 1710. Russian rule was confirmed by the Treaty of Nystad in 1721. However, the legal system, Lutheran church, local governments, and education mostly stayed German until the late 19th century.

The Russian era was a "golden age" for the German elites. They owned most of the land and businesses. They controlled the serfs and dominated the cities. They got along well with Russian authorities. The Germans were Lutherans, like most Estonians, and controlled the Lutheran churches.

By 1819, serfdom was ended in the Baltic provinces. This was the first time in the Russian empire. Peasants could now own land or move to cities. This helped create a local national identity and culture. Estonia was part of a national awakening happening across Europe.

Tartu was a diverse city with Russians, Germans, and Estonians. Different religions and scholars were active at the university. Students did not seem interested in the Russification programs of the 1890s.

Enlightenment and Estonian Identity (1750–1840)

Educated Germans in Estonia brought Enlightenment ideas like rational thinking, freedom, and equality. The French Revolution inspired them to create literature for peasants. When serfdom ended in southern Estonia (1816) and northern Estonia (1819), people debated the future of former enslaved people.

While many Baltic Germans thought Estonians would blend in with them, others admired Estonia's ancient culture. This period led to Estonian literature moving from religious topics to newspapers for everyone.

National Awakening: A New Spirit

A cultural movement began to use Estonian in schools. All-Estonian song festivals started in 1869. A national literature in Estonian developed. Kalevipoeg, Estonia's national epic, was published in 1861.

In 1889, the Russian government started a policy of Russification. Many German legal institutions were changed or had to use Russian. For example, the University of Tartu was affected.

When the Russian Revolution of 1905 reached Estonia, Estonians asked for freedom of the press and assembly. They also wanted universal voting rights and national self-rule. Estonians gained little, but the time between 1905 and 1917 allowed them to push for their own state.

Road to Independence (1917–1920)

Estonia became a unified political area after the Russian February Revolution of 1917. As the Russian Empire fell during World War I, Russia's Provisional Government gave self-rule to a unified Estonia in April. Elections for a temporary parliament, Maapäev, were held. On November 5, 1917, Estonian Bolshevik leader Jaan Anvelt took power by force, making the Maapäev go underground.

In February 1918, after peace talks failed, Germany occupied mainland Estonia. Bolshevik forces went back to Russia. Between the Russian army leaving and German troops arriving, the Estonian National Council issued the Estonian Declaration of Independence in Pärnu on February 23, 1918.

War of Independence: Fighting for Freedom

After the German troops left in November 1918, an Estonian Provisional Government took over. But a few days later, the Red Army invaded, starting the Estonian War of Independence (1918–1920). The Estonian army pushed the Red Army out of Estonia by February 1919. On April 5–7, 1919, the Estonian Constituent Assembly was elected.

Victory and a New Republic

On February 2, 1920, the Treaty of Tartu was signed. Russia gave up all claims to Estonia forever. The first Constitution of Estonia was adopted on June 15, 1920. The Republic of Estonia was recognized by other countries and joined the League of Nations in 1921.

Between Wars (1920–1939)

Estonia's first period of independence lasted 22 years. It made many changes in its economy, society, and politics. The most important was the land reform in 1919. Large estates owned by the Baltic nobility were given to peasants and war volunteers. Estonia's main markets became Scandinavia, the UK, and Western Europe.

The first constitution (1920) set up a parliamentary government. The parliament (Riigikogu) had 100 members elected for three years. Between 1920 and 1934, Estonia had 21 governments.

In the 1930s, an anti-communist and anti-parliamentary group called the Vaps Movement grew. In October 1933, a vote on changing the constitution, started by the Vaps Movement, was approved. The movement wanted a president instead of a parliament. However, Konstantin Päts, the Head of State, stopped them with a coup on March 12, 1934. He then ruled as an authoritarian leader. Political parties were banned, and parliament did not meet. The Vaps Movement was banned in 1935.

This time was one of great cultural growth. Estonian language schools were set up, and arts flourished. In 1925, a law gave cultural freedom to minority groups with at least 3,000 people, including Jews. Historians note that the lack of violence after "700 years of German rule" suggests it was not harsh.

Estonia tried to stay neutral. But this did not matter after the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on August 23, 1939. In this agreement, the two powers divided countries between them. Estonia fell into the Soviet "sphere of influence". On September 24, 1939, the Soviet Union threatened Estonia with war unless it allowed military bases. Estonia agreed to avoid conflict.

World War II (1939–1944)

After the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Soviet warships appeared off Estonian ports on September 24, 1939. Soviet bombers flew threateningly over Tallinn. Moscow demanded that Estonia allow the USSR to set up military bases and station 25,000 troops. Estonia's government accepted on September 28, 1939.

Becoming Part of the Soviet Union (1940)

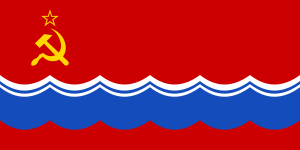

The Republic of Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union in June 1940.

On June 12, 1940, the Soviet Baltic Fleet was ordered to block Estonia completely. On June 14, 1940, Soviet bombers shot down a Finnish passenger plane flying from Tallinn to Helsinki. It carried diplomatic mail from US offices.

On June 16, 1940, the Soviet Union invaded Estonia. Molotov accused the Baltic states of plotting against the Soviet Union. He gave Estonia an ultimatum to form a Soviet-approved government.

The Estonian government decided not to resist, to avoid bloodshed. Estonia accepted the ultimatum. The Red Army entered Estonia on June 17. About 90,000 more troops entered the next day. The military occupation became official with a communist coup, supported by Soviet troops. Elections followed where only pro-Communist candidates were allowed. The new parliament declared Estonia a Socialist Republic on July 21, 1940. It asked to join the Soviet Union. Estonia was formally taken into the Soviet Union on August 6 and renamed the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The Soviet authorities immediately started a time of terror. In the first year (1940–1941), over 8,000 people were arrested, including many politicians and military officers. About 2,200 were executed in Estonia. Most others were sent to Gulag prison camps in Russia, where few survived. On June 14, 1941, about 10,000 Estonian civilians were sent to Siberia. Nearly half of them died. Of 32,100 Estonian men forced into the Soviet army in 1941, almost 40% died in "labour battalions" from hunger, cold, and overwork.

Estonian graveyards and monuments were destroyed. The Tallinn Military Cemetery had most gravestones from 1918-1944 destroyed. Other old cemeteries were also destroyed.

Many countries, including the United States, did not recognize the Soviet takeover of Estonia. They continued to recognize Estonian diplomats who worked for the former government.

German Occupation (1941–1944)

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the German army reached Estonia in July. Most Estonians welcomed the Germans, hoping for independence. But it soon became clear that Estonia would not be free. Estonia became part of the German-occupied "Ostland".

The first excitement about being free from Soviet rule quickly faded. The Germans had little success getting volunteers. A draft was started in 1942. This led to about 3,400 men fleeing to Finland to fight in the Finnish Army instead of joining the Germans. The Finnish Infantry Regiment 200 was formed from Estonian volunteers in Finland.

By January 1944, the Soviet Army had pushed the front almost back to the Estonian border. Narva was evacuated. Jüri Uluots, the last legal prime minister of Estonia before Soviet rule, asked all able-bodied men to join the military. 38,000 volunteers signed up. Several thousand Estonians from the Finnish army returned to defend Estonia against the Soviet advance. They hoped this war would gain Western support for Estonia's independence.

The SS Estonian legion, formed in 1942, became a full division in 1944. Estonian units fought to defend the Narva line in 1944.

As the Germans retreated on September 18, 1944, Jüri Uluots took over as president. He appointed a new government and sought recognition from the Allies. On September 22, 1944, the Soviet Red Army re-occupied Tallinn. The new Estonian government fled to Stockholm, Sweden. It worked as an exile government until 1992.

The Holocaust in Estonia

Jewish people began settling in Estonia in the 19th century. When the Republic of Estonia was created in 1918, it was a new era for Jews. About 200 Jews fought for Estonia's independence. Estonia showed tolerance to all its peoples. In 1925, a law gave cultural freedom to minority groups. The Jewish community quickly gained cultural freedom.

In 1940, when the Soviets occupied Estonia, there were about 2,000 Estonian Jews. Many were sent to Siberia with other Estonians. When the Nazis invaded, they intended to kill many Jews in the Baltic countries. Jews from other parts of Europe were sent to Estonia to be killed. Of the 4,300 Jews in Estonia before the war, between 1,500 and 2,000 were caught by the Nazis. An estimated 10,000 Jews were killed in Estonia after being sent there from Eastern Europe.

Markers were placed for the 60th anniversary of mass killings at camps like Lagedi, Vaivara, and Klooga in September 1944.

Other Minorities During and After WWII

The Baltic Germans had already moved to Germany before the war, following Hitler's orders.

Almost all remaining Estonian Swedes fled in August 1944, often in small boats to the Swedish island of Gotland.

The Russian population grew a lot after the war.

Soviet Estonia (1944–1991)

Stalinism: Hard Times

Estonia suffered huge losses in World War II. Ports were destroyed, and much industry and railways were damaged. Estonia's population dropped by one-fifth, about 200,000 people. About 80,000 people fled to the West. More than 30,000 soldiers died. In 1944, Russian air raids destroyed Narva and a third of Tallinn. By late 1944, Soviet forces began a new wave of arrests and executions of people seen as disloyal.

An anti-Soviet guerrilla group called the Metsavennad (Forest Brothers) formed in the countryside. It was strongest from 1946–48. It's thought that 30,000–35,000 people were part of this group at different times. The last Forest Brother was caught in 1978.

In March 1949, 20,722 people (2.5% of the population) were sent to Siberia. By the early 1950s, the Soviet rulers had stopped the resistance movement.

After the war, the Communist Party of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (ECP) became the most important group. The number of ethnic Estonians in the ECP dropped from 90% in 1941 to 48% in 1952.

Khrushchev Era: Some Changes

After Stalin died, more ethnic Estonians joined the Communist Party. By the mid-1960s, about 50% of members were Estonians. Before perestroika, the ECP had about 100,000 members. Less than half were ethnic Estonians.

One good change after Stalin was allowing citizens to contact foreign countries in the late 1950s. In the 1960s, Estonians could watch Finnish television. This "window to the West" gave Estonians more news and access to Western culture than other groups in the Soviet Union.

Brezhnev Era: Russification Concerns

In the late 1970s, Estonians worried about their language and identity being lost due to Russification. By 1981, Russian was taught in first grade in Estonian schools and in pre-schools.

1980 Moscow Olympic Games

Tallinn hosted the sailing events at the 1980 Summer Olympics. This caused debate because many governments did not recognize Estonia as part of the USSR. For the Olympics, new sports buildings were built in Tallinn. Other improvements included Tallinn Airport, Hotell Olümpia, Tallinn TV Tower, and Linnahall.

Gorbachev Era: Winds of Change

By the start of the Gorbachev era, Estonians were very worried about their culture surviving. The Communist Party stayed strong at first but weakened in the late 1980s. Other political groups and parties started to form. The first and most important was the Estonian Popular Front, created in April 1988. It had its own goals and many supporters. The Greens and the Estonian National Independence Party soon followed.

Restoring Independence

The Estonian Sovereignty Declaration was issued on November 16, 1988. By 1989, many new parties were forming. The republic's Supreme Soviet became a real law-making body. It passed a declaration of sovereignty (1988), a law on economic independence (1989), and a language law making Estonian the official language (1989).

Despite these changes, different groups of Estonians had different political ideas. The Popular Front wanted to declare Estonia a new "third republic." But this idea lost support over time.

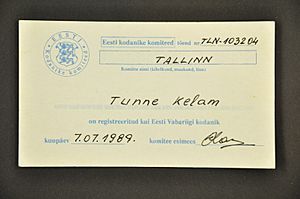

A group called the Estonian Citizens' Committees Movement started in 1989. Their goal was to register all pre-war citizens of Estonia and their families. They wanted to hold a Congress of Estonia. They argued that the Soviet system was illegal. They said that hundreds of thousands of Estonians were still citizens of the Estonian Republic, which still existed legally. Many local citizens' committees were elected. By early 1990, over 900,000 people had registered as citizens.

In spring 1990, two free elections were held. On February 24, 1990, the 464-member Congress of Estonia was elected by registered citizens. The Congress met in Tallinn in March 1990. It passed 14 declarations. A 70-member committee (Eesti Komitee) was elected.

In March 1991, a vote was held on independence. This was a bit controversial. Allowing Russian immigrants to vote was debated. But all major parties supported the vote to send a strong message to the world. All residents of Estonia could vote. The result strongly supported independence. 82% of voters participated, and 64% supported independence.

Most Russian-speaking immigrants did not support full independence. But by early 1990, only a small number of ethnic Estonians were against it.

In the March 18, 1990, elections for the 105-member Supreme Soviet, all residents could vote. This included Soviet-era immigrants and about 50,000 Soviet troops. The Popular Front, led by Edgar Savisaar, won a majority.

On May 8, 1990, the Supreme Council of Estonia changed its name to the Republic of Estonia. During the attempted August coup in the USSR, Estonia kept its telecommunications working. This gave the West a clear view of events. It also helped Estonia get quick Western support and recognition for its "confirmation" of independence on August 20, 1991. August 20 is now a national holiday in Estonia. Russia recognized Estonia's independence on August 25, 1991. The State Council of the Soviet Union recognized it on September 6.

The debates about whether Estonia would be a new republic or a continuation of the first were not finished. A compromise was reached. The declaration would "confirm" Estonia as an independent state. It would also state its willingness to reestablish diplomatic relations.

After more than three years of talks, Russian armed forces left Estonia on August 31, 1994. Since regaining independence, Estonia has had many governments and prime ministers.

Since the last Russian troops left in 1994, Estonia has built economic and political ties with Western Europe. Estonia began talks to join the European Union in 1998 and joined in 2004. It also became a member of NATO.

Estonian Government Today (1992–Present)

On June 28, 1992, Estonian voters approved a new constitution. It set up a parliamentary government with a president as head of state and a prime minister as head of government. The Riigikogu, a single-chamber parliament, is the highest state authority. It creates and approves laws. The prime minister is fully responsible for their cabinet.

Meri Presidency and Laar Premiership (1992–2001)

Parliamentary and presidential elections were held on September 20, 1992. About 68% of voters participated. Lennart Meri, a famous writer and former Foreign Minister, won and became president. He chose 32-year-old historian Mart Laar as prime minister.

In 1992 and 1995, the Riigikogu renewed Estonia's 1938 citizenship law. Mart Laar's government started quick reforms. They privatized many state-owned businesses and reduced the government's role in the economy. After an initial drop, the Estonian economy began to grow in 1995. These changes had a social cost. In 1993, pensioners protested in Tallinn because their pensions were very low.

The opposition won the 1995 election but largely continued the previous government's policies.

In 1996, Estonia signed a border agreement with Latvia and worked on one with Russia. President Meri was re-elected in 1996. In the 1999 parliamentary elections, the Estonian Centre Party won the most seats. Mart Laar became prime minister again, leading a coalition. This coalition lasted until Laar resigned in December 2001.

Rüütel Presidency and Siim Kallas Government (2001–2002)

In fall 2001, Arnold Rüütel became President. In January 2002, Prime Minister Laar stepped down. On January 28, 2002, a new government was formed. It was a coalition of the centre-right Estonian Reform Party and the Centre Party. Siim Kallas from the Reform Party became Prime Minister.

In 2003, Estonia joined NATO.

Juhan Parts Government (2003)

After the 2003 elections, the Centre Party and Res Publica each won 28 seats. The right-of-center parties won more seats overall. President Rüütel asked Juhan Parts, leader of Res Publica, to form a government. A coalition government of Res Publica, the Reform Party, and the People's Union of Estonia was formed on April 10.

On September 14, 2003, Estonians voted in a referendum on joining the European Union. 64% of voters participated, and 66.83% voted yes. Estonia joined the EU on May 1, 2004.

In February 2004, the People's Party Moderates changed their name to the Social Democratic Party of Estonia.

Andrus Ansip Government (2004)

On March 24, Prime Minister Juhan Parts resigned after a vote of no confidence against his Justice Minister. On April 4, 2005, President Rüütel nominated Reform Party leader Andrus Ansip as Prime Minister. Ansip formed a government with his Reform Party, the People's Union, and the Centre Party. The parliament approved him on April 12, 2005.

On May 18, 2005, Estonia signed a border treaty with Russia. Estonia ratified it, but Russia later said it would not follow it. This was because Estonia added a statement about the Soviet occupation. The issue is still unresolved.

In April 2006, the Fatherland Union and Res Publica decided to form a single party, the Union of Pro Patria and Res Publica.

In September 2006, Toomas Hendrik Ilves was elected as the new president.

2007 Elections and EU Membership

The 2007 elections showed the Reform Party gaining seats. The Centre Party stayed the same, while the Union of Pro Patria and Res Publica lost seats. The Social Democrats gained seats, and the Greens entered parliament. The Centre Party, led by Edgar Savisaar, was increasingly excluded from cooperation. This was due to its ties with Putin's United Russia party and other issues.

On September 14, 2003, Estonians voted to join the European Union. With 64% of voters, 66.83% voted yes. Estonia joined the EU on May 1, 2004.

In its first European Parliament elections in 2004, Estonia elected three members for the Social Democratic Party. Voter turnout was low at 26.8%. In the 2009 European Parliament election, turnout was higher at 43.9%. The Centre Party won two seats. The Reform Party, Union of Pro Patria and Res Publica, Social Democratic Party, and an independent candidate each won one seat.

On January 1, 2011, Estonia adopted the euro. This was seen as a good sign during a global financial crisis. The government cut public service salaries. Estonian teachers were the only ones to protest, so their cuts were limited.

Estonian euro coins began circulating on January 1, 2011. Estonia was the first former Soviet republic to join the eurozone. On May 12, 2010, the European Commission announced Estonia met all criteria. On July 13, 2010, Estonia received final approval to adopt the euro.

As a member of the eurozone, NATO, and the European Union, Estonia is very connected to Western European organizations.

Estonia–Russia Relations (Late 2000s)

Estonia–Russia relations remain tense. According to Estonia's Internal Security Service, Russian influence operations in Estonia involve financial, political, economic, and spying activities. These aim to influence Estonia's decisions in ways that favor Russia. Russia's information campaigns have caused divisions in Estonian society. For example, some Russian speakers rioted over moving the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn monument. Estonia saw the 2007 cyberattacks on Estonia as an attempt to influence its government. Russia denied direct involvement, but hostile talk in the media encouraged attacks. After the cyberattacks, the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE) was set up in Tallinn.

From 2011 to Present

In August 2011, President Toomas Hendrik Ilves was re-elected for a second five-year term. The center-right Reform Party was the largest party in the 2011 and 2015 elections. Estonian Prime Minister Andrus Ansip resigned in March 2014 after nine years. He wanted his successor to lead the Reform Party into the 2015 elections. In April 2014, Taavi Rõivas of the Reform Party became the new prime minister.

In October 2016, Estonia's parliament elected Kersti Kaljulaid as the new president. The president's role is mostly ceremonial. In November 2016, Jüri Ratas, chairman of the Centre Party, became the new prime minister. This happened after Prime Minister Taavi Rõivas lost a vote of confidence.

In March 2019, the center-right opposition Reform Party won the Estonian parliamentary election. The ruling Centre Party came second. The far-right Conservative People's Party of Estonia (EKRE) came third. After the election, Prime Minister Ratas formed a new coalition government with EKRE and the right-wing Isamaa party.

In January 2021, Prime Minister Jüri Ratas resigned due to a corruption scandal in his Centre Party. The leader of the Reform Party, Kaja Kallas, formed a new coalition government with the Reform and Center parties. She became the first female prime minister of Estonia. Her father, Siim Kallas, founded the Reform Party and was prime minister from 2002–2003.

Female Leadership in 2021

After the new government formed in 2021, Estonia was unique. Both its president, Kersti Kaljulaid, and prime minister, Kaja Kallas, were women. The cabinet also had several women in important roles, like foreign minister and finance minister. However, Mr. Alar Karis became Estonia's sixth President on October 11, 2021.

Since 2022

In July 2022, Prime Minister Kaja Kallas formed a new three-party coalition. It included her liberal Reform Party, the Social Democrats, and the conservative Isamaa party. Her previous government had lost its majority.

In March 2023, the Reform Party, led by Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, won the parliamentary election. They got 31.4% of the vote. The far-right Conservative People's Party came second, and the Centre Party was third. In April 2023, Kallas formed her third government. It included the Reform Party, the liberal Estonia 200, and the Social Democratic (SDE) parties.

Time line

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Estonia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Estonia para niños

- Bishopric of Dorpat

- Dissolution of the Soviet Union

- German occupation of Estonia during World War II

- Hanseatic League

- History of Denmark

- History of Europe

- History of Finland

- History of Germany

- History of Latvia

- History of Lithuania

- History of Russia

- History of Sweden

- History of the European Union

- List of rulers of Estonia

- Livonian Crusade

- Livonian Order

- Politics of Estonia

- President of Estonia

- President-Regent

- Prime Minister of Estonia

- Soviet Union

- Timeline of Tallinn

- Ungannians

- Vironians

- Women in Estonia

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |