History of Indigenous Australians facts for kids

The history of Indigenous Australians began at least 65,000 years ago. That's when people first came to the land we now call Australia. This story is about the Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples. These are two big groups, but they have many smaller groups with different languages and cultures.

Scientists are still discussing exactly how the first people arrived in Australia. Some think they came from Africa a very long time ago. They probably traveled through Southeast Asia to get to Australia. Aboriginal Australians don't seem to be closely related to Asian or Melanesian people. However, Torres Strait Islander people do have some family links to Melanesian groups. There's also evidence of people from New Guinea and the islands trading and marrying with Australians in the far north.

Before Europeans arrived in 1788, between 300,000 and 1.25 million Indigenous people lived in Australia. Over 65,000 years, an estimated 1.6 billion people lived here. The most populated areas were the same coastal regions that are busy today, especially around the Murray River. In the early 1900s, many thought the Aboriginal population would disappear. Their numbers dropped from around 1788 to just 50,000 by 1930. This huge drop was due to diseases like smallpox and also conflicts and killings by settlers.

After European settlement, many coastal Indigenous groups were forced off their lands or their ways of life changed. Traditional Aboriginal life continued strongest in places like the Great Sandy Desert, where fewer Europeans settled. Even though the Aboriginal Tasmanians almost vanished, other Aboriginal Australian peoples kept their communities strong across Australia.

Contents

How Did People First Come to Australia?

Scientists believe the first people came to Australia when it was connected to New Guinea. This huge landmass was called the Sahul continent. Even then, they would have needed to cross some sea areas. It's also possible they traveled by hopping between islands, reaching North Western Australia through Timor.

A study from 2021 mapped the likely paths people took. It suggests it took 5,000 to 6,000 years to reach Tasmania. This was about 60,000 years ago, starting from the Kimberley region in Western Australia. The total human population could have been as high as 6.4 million people across the whole Sahul continent.

The study suggests two main routes. One, the "southern route," went into the Kimberley, Pilbara, and Arnhem Land. From there, it moved to the Great Sandy Desert and then towards the center of Australia. It also led to the southwest parts, like Margaret River. The "northern route" crossed the area of the current Torres Strait. It then split, with one path going to Arnhem Land and another down the East Coast. These ancient paths are similar to modern highways in Australia.

The oldest known place showing humans in Australia is Madjedbebe. Evidence suggests people lived there possibly 65,000 years ago, and definitely by 50,000 years ago. At Madjedbebe and Nauwalabila I, scientists found pieces of ochre used by artists 60,000 years ago. Near Penrith, stone tools dating back 45,000 to 50,000 years have been found. In 1999, tools found on Rottnest Island were dated to 70,000 years ago. A 2018 study found evidence of human life at Karnatukul in the Little Sandy Desert in WA around 50,000 years ago. This was much earlier than thought. There is also evidence of changes in how fire was used in Australia between 70,000 and 100,000 years ago. All this suggests people arrived before 60,000 years ago.

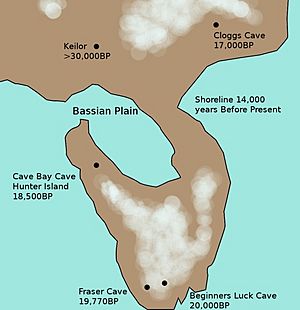

Humans reached Tasmania about 40,000 years ago. They walked across a land bridge from the mainland during the last ice age. When the seas rose about 12,000 years ago, the land bridge disappeared. The people in Tasmania were then cut off from the mainland until Europeans arrived.

Short Aboriginal tribes lived in the rainforests of North Queensland. The Tjapukai people from the Cairns area are a well-known group.

Mungo Man, found near Lake Mungo in New South Wales, is the oldest human remains found in Australia. He is believed to be at least 40,000 years old. Stone tools found there are estimated to be about 50,000 years old. Since Lake Mungo is in southeastern Australia, many scientists believe humans must have arrived in northwestern Australia thousands of years earlier.

Big Changes Around 4,000 Years Ago

The dingo arrived in Australia about 4,000 years ago. It's thought that Asian seafarers brought them. The dingo is believed to have caused the extinction of the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger) on mainland Australia. Around the same time, there were changes in language. The Pama-Nyungan language family spread across most of the mainland. Stone tool technology also changed, with people using smaller tools.

A 2013 study suggested that Aboriginal Australians, people from New Guinea, and the Mamanwa people from the Philippines are closely related. They separated from a common origin about 36,000 years ago. The study also showed that Aboriginal genomes have up to 11% Indian DNA. This suggests that people from India and Northern Australia had contact around 4,230 years ago. Changes in tools and food processing around this time also hint at possible migration from India.

However, a 2016 study disagreed about the Indian gene flow. It found no strong evidence of recent gene flow from India into Australia. The study did confirm that gene flow across the Torres Strait is likely. This means people from New Guinea and Australia probably had contact.

Life Before European Settlement

Australia's Changing Landscape

When people first arrived in northwest Australia, it had open tropical forests and woodlands. After about 10,000 years of stable weather, temperatures started to cool, and an ice age began. Around 25,000 to 15,000 years ago, during the coldest part of the ice age, sea levels dropped about 140 meters. Australia was connected to New Guinea. The Kimberley region was separated from Southeast Asia by a strait only about 90 km wide. Rainfall was much lower, and plants needed twice as much water to grow.

The Kimberley and the exposed Sahul Shelf were covered by huge grasslands. Most of Australia was extreme desert and sand dunes. Only about 15% of Australia had trees. Some tropical rainforests survived in isolated parts of Queensland.

Tasmania was mostly cold grasslands. It's believed that the Aboriginal population might have shrunk during this time. People survived in scattered "refugia" (safe places) where modern plants and populations could live. Corridors between these safe places helped people stay in contact. After the ice age, heavy rains returned. Then, around 5,500 years ago, a huge drought lasted 1,500 years. Around 4,000 years ago, reliable rains returned, giving Australia its current climate.

After the Ice Age, Aboriginal people along the coast, from Arnhem Land, the Kimberley, and southwest Western Australia, tell stories of their lands being covered by the rising sea. This event separated the Tasmanian Aboriginal people. It also likely caused the disappearance of Aboriginal cultures on the Bass Strait Islands and Kangaroo Island. In the interior, the end of the Ice Age may have led to people moving back into the desert areas. This might have helped spread the Pama–Nyungan language family. There was also a long history of contact between people from Papua New Guinea, Torres Strait Islanders, and Aboriginal people in Cape York Peninsula.

Indigenous Australians lived through huge climate changes and adapted well. There is still debate about how much they changed the environment. One big discussion is about their role in the extinction of large marsupials called megafauna. Some say climate change killed them. Others say humans hunted them easily because they were big and slow. A third idea is that humans changed the environment, especially by using fire, which indirectly led to their extinction.

Oral history shows that Indigenous Australian culture has continued for at least 10,000 years. This is seen in stories that match real events, like changes in sea levels, stories about megafauna, and comets.

How People Used the Land

The arrival of the dingo, possibly as early as 3500 BCE, shows that contact with Southeast Asian peoples continued. The dingo's closest genetic relatives are wild dogs from Thailand. This contact wasn't just one-way, as kangaroo ticks found on these dogs show. Dingoes started in Asia.

Most scientists now believe that the arrival of Aboriginal people and their use of fire-stick farming led to the extinction of some animals. However, fossil research from 2017 shows that Aboriginal people and megafauna lived together for at least 17,000 years. Aboriginal Australians used fire for many reasons: to help edible plants grow, to reduce big bushfires, to make travel easier, to get rid of pests, for ceremonies, and for war. There is still debate about how much this burning changed the plants across the land.

What Did People Eat?

Aboriginal Australians ate foods found naturally in their area. They knew exactly when, where, and how to find everything edible. Experts who studied their diet found it was very healthy and balanced. But finding food took effort. In some areas, men and women spent half to two-thirds of each day hunting or gathering. Women used digging sticks and bags or wooden coolamons to collect food. Men hunted larger animals like kangaroos and emus with spears, clubs, or boomerangs. They were excellent trackers and stalkers, moving quietly and staying downwind.

Fish were caught by hand, by stunning them with poisonous plants, or using spears, nets, and traps. Hooks made from bone or shell were used along the coasts. Large sea animals like dugongs and turtles were caught with harpoons. Both Torres Strait Islanders and mainland Aboriginal peoples were mostly hunter-gatherers. However, Torres Strait Islanders also grew bananas. Aboriginal Australians along the coast and rivers were skilled fishermen. Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people used dingoes to help with hunting and for warmth.

In present-day Victoria, two groups farmed eels using complex pond systems. One was on the Murray River, and the other near Hamilton. They traded with other groups from far away. A main hunting tool was the spear, often launched with a woomera. Boomerangs were also used. The non-returning boomerang was powerful enough to injure or kill a kangaroo.

On mainland Australia, no animal other than the dingo was domesticated. However, Torres Strait Islanders used domestic pigs and cassowaries. The typical Aboriginal diet included many foods, like kangaroos, emus, wombats, goannas, snakes, birds, and insects like honey ants and witchetty grubs. Many plant foods like taro, coconuts, nuts, fruits, and berries were also eaten.

Culture and Community Life

Permanent villages were common for most Torres Strait Island communities. In some areas, mainland Aboriginal Australians also lived in semi-permanent villages. This was usually in less dry areas where fishing provided enough food for a settled life. Places like Budj Bim grew into quite large settlements. Most Indigenous communities were semi-nomadic. They moved in a regular cycle over a defined territory, following seasonal food sources. They returned to the same places each year. Archaeologists have found that some places were visited annually for thousands of years. In drier areas, Aboriginal Australians were nomadic, traveling widely for scarce food.

There is evidence that Indigenous culture changed over time. Rock paintings in northern Australia show different styles from different historical periods. There are also important rock paintings in the Sydney area dating back about 5,000 years.

Many Indigenous communities had very complex family structures and strict rules about marriage. In traditional societies, men had to marry women from specific family groups. This system is still alive in many Central Australian communities. To help people find partners, many groups would gather annually. These gatherings, called corroborees, were for trading goods, sharing news, and arranging marriages with ceremonies. This helped strengthen family ties and prevented inbreeding in small, moving groups.

European Arrival and Its Impact (1770–1850s)

The first contact between British explorers and Indigenous Australians happened in 1770. Lieutenant James Cook met the Guugu Yimithirr people near what is now Cooktown. Cook wrote that he claimed the east coast of Australia for Britain, naming it New South Wales. However, his orders were to claim land "with the Consent of the Natives." The British government did not see Aboriginal Australians as owners of the land because they didn't farm it.

British colonisation of Australia began at Port Jackson in 1788. Governor Arthur Phillip and the First Fleet arrived. The Governor was told to be friendly with the Indigenous people and punish anyone who harmed them.

The Eora people, who first saw the British, were surprised and then became aggressive. For the next two years, the Eora generally avoided the British. They were upset that the British entered their lands and took resources without asking. Some contact did happen, with gifts exchanged. After a year, Phillip decided to capture Indigenous people to teach them English. This led to the kidnapping of Arabanoo and Bennelong. Bennelong later traveled to England. A Kuringgai man named Bungaree also sailed with Europeans. After a huntsman was killed, possibly by Pemulwuy, Phillip ordered 10 men to be captured and killed. None were found.

The first major disaster for Aboriginal people came in April 1789. A disease, probably smallpox, hit the Aboriginal peoples around Port Jackson. Before this, the First Fleet's population was equal to the Eora. After the disease, the settlers equaled all Indigenous people on the Cumberland Plain. By 1820, the settler population of 30,000 was as much as the entire Indigenous population of New South Wales.

A generation after colonisation, the Eora, Dharug, and Kuringgai populations were greatly reduced. They mostly lived on the edges of European society. The biggest cause of death was disease, followed by killings by settlers and conflicts between Indigenous groups. This population loss was made worse by a very low birth rate. An estimated 80% of the population was lost. This made it hard to keep traditional family systems and ceremonies going. Survivors often lived in poor health in tents and shacks around towns.

Aboriginal Tasmanians first met Europeans when the Baudin expedition arrived in 1802. The French explorers were friendlier than the British. Earlier, in 1800, European whalers had kidnapped Aboriginal women on the Bass Strait islands. The local Indigenous people also sold women to sailors. Later, the descendants of these women would be the last survivors of Tasmanian Indigenous people.

Attempts at Assimilation

The idea of "assimilation" meant trying to make Indigenous people live like Europeans. Governor Lachlan Macquarie started this in 1814. He created the Native Institution in Blacktown. Its goal was to "civilize" Aboriginal people and make them more like Europeans. Children were sent to a boarding school there. One girl, Maria, even won a prize in a school exam in 1819, beating European children. However, the institution closed soon after. Macquarie also tried to settle 16 Kuringgai families with land and houses, but they soon sold the farms and left.

Christian missions were also started. These missions tried to learn Indigenous languages. For example, the Gospel of Luke was translated into Awabakal in 1831. Missions also offered food and safety. But when supplies ran out, Indigenous people often left to find work on farms. Some missionaries took children without permission to teach them in dormitories.

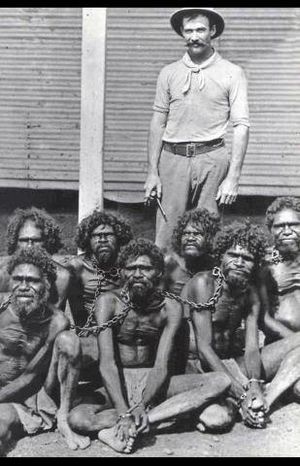

The government started giving out blankets in the 1830s but stopped in 1844 to save money. It also created Indigenous police units, called the Australian native police. These forces killed hundreds of Indigenous people.

In 1833, a British committee demanded better treatment for Indigenous people. They called them "original owners." This led the British government to create the office of the Protector of Aborigines in 1838. This effort ended by 1857. However, it did lead to the Waste Land Act of 1848, which gave Indigenous people some rights and reserves on the land.

Some Europeans also assimilated into Indigenous cultures. William Buckley, an escaped convict, lived with the Wautharong people near Melbourne for 32 years. James Morrill, an English sailor, lived with an Aboriginal clan in northeastern Australia for 17 years. He learned their language and customs. Indigenous peoples also widely adopted the European dog.

Conflicts and Wars

On the mainland, long conflicts followed European settlement. An estimated 40,000 Indigenous Australians and 2,000 to 2,500 settlers died in these wars. However, recent studies suggest Indigenous deaths in Queensland may have been much higher. Battles and massacres happened across Australia, but they were especially bloody in Queensland. It's estimated that up to 3,000 white people were killed by Aboriginal Australians. Some Indigenous people also allied with the colonists against other Indigenous groups. Colonisation made fighting between Indigenous groups worse. This was because they were forced from their lands, and diseases were sometimes blamed on enemy magic. Indigenous gun ownership was banned in New South Wales in 1840, but the British government overturned this.

In 1790, an Aboriginal leader named Pemulwuy in Sydney fought back against the Europeans. He led a guerrilla-style war against the settlers. These wars, known as the Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars, lasted 26 years, from 1790 to 1816. After Pemulwuy's death in 1802, his son Tedbury continued the fight until 1810. This conflict led to rules banning Aboriginal groups of more than six people and forbidding them from carrying weapons near settlements. Beyond the Cumberland Plain, violence first broke out at Bathurst against the Wiradjuri people. Martial law was declared in 1822.

In Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), conflict began in 1824. Indigenous warriors killed 24 Europeans by 1826. In 1828, martial law was declared, and settler groups took revenge. On the Indigenous side, Musquito led the Oyster Bay tribe against the settlers. Tarenorerer was another leader. The Black War was fought as a guerrilla war by both sides. It killed 600 to 900 Aboriginal people and over 200 European colonists. This almost wiped out the island's Indigenous population. The near destruction of the Aboriginal Tasmanians has led to debate among historians about whether the Black War was an act of genocide.

In Swan River Colony (near Perth), conflict occurred. The government offered settlers weapons. A group was sent against the Pindjarup people in 1834.

Diseases and Their Impact

Deadly infectious diseases like smallpox, influenza, and tuberculosis were major causes of Aboriginal deaths. Smallpox alone killed more than 50% of the Aboriginal population. Other diseases included dysentery, scarlet fever, typhus, measles, whooping cough, and influenza. Health also declined due to more use of flour and sugar instead of diverse traditional diets, leading to poor nutrition.

In April 1789, a big smallpox outbreak killed many Indigenous Australians. It spread between the Hawkesbury River, Broken Bay, and Port Hacking. Based on journals from the First Fleet, it seems the Aboriginal people of the Sydney region had never seen the disease before and had no protection against it. They couldn't understand or fight the sickness. They often fled, leaving the sick with some food and water. As groups fled, the disease spread further along the coast and inland. This had a terrible effect on Aboriginal society. Many skilled hunters and gatherers died, and those who survived the first outbreak began to starve.

Some people have suggested that Makassan fishermen accidentally brought smallpox to Australia's north. However, diseases like smallpox need many people living close together to spread. Also, sick people couldn't walk far. So, it's unlikely it spread across desert trade routes. A more likely source was "variolas matter" (smallpox virus) that Surgeon John White brought with the First Fleet. It's unknown how it might have spread. Some have even thought the vials were accidentally or intentionally released as a "biological weapon." In 2014, Christopher Warren concluded that British marines most likely spread smallpox, possibly without telling Governor Phillip.

Changes to Economy and Environment

In 1822, the British government lowered taxes on Australian wool. This led to more sheep farming and more immigrants. Sheep thrived in the dry western plains. Settlers caused big environmental changes. Their cattle ate local grasses and trampled waterholes. Important traditional foods like murnong disappeared, and new weeds spread. Meat sources like kangaroo were replaced by cattle. In response, Indigenous people sometimes took settler resources, like sheep, and even raised their own flocks.

New European goods also changed traditional ways of life. For example, steel axes replaced traditional stone ones. This meant older men, who usually controlled access to stone axes, lost some authority. Settlers and missionaries gave new axes to younger people in exchange for work. This also weakened old trading networks.

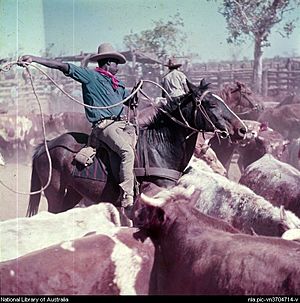

After losing their lands, Indigenous people often moved to pastoral stations, missions, and towns. They were often forced by a lack of food. Tobacco, tea, and sugar also attracted Indigenous people to settlers. After some handouts, settlers demanded work in return for food. Indigenous people worked cutting timber, herding sheep, and as stockmen. They also worked as fishermen, water carriers, domestic servants, and whalers. However, the European work ethic was not part of their culture. Working more than needed for immediate benefits was not seen as important. Their pay was also unequal to settlers, often just rations or less than half the wage. Women had been the main food providers in Indigenous families. Their roles lessened as men became the main recipients of wages and rations. Women could mostly find European-style domestic work.

Northern Expansion (1850s–1940s)

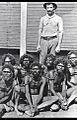

By 1850, southern Australia was settled by new immigrants. European explorers began to explore the Top End and Cape York Peninsula. By 1862, they had crossed the continent and entered the Kimberley and Pilbara regions. They claimed new lands, mapped them, and opened them for farmers. North Queensland was settled in the 1860s, Central Australia and the Northern Territory in the 1870s, and the Kimberley in the 1880s. This again led to violent clashes with Indigenous peoples. However, because these new areas were dry and remote, settlement was slower. The European population remained small and often fearful. Few police protected the Indigenous population. In North Queensland, it's estimated that 15% of the first farmers were killed in Indigenous attacks. But 10 times more Indigenous people died. In the Gulf Country, over 400 violent Indigenous deaths were recorded between 1872 and 1903.

In the older settled southern parts of Australia, about 20,000 Indigenous people remained by the 1920s. About half were of mixed ancestry. One-fifth lived on reserves. Most others lived in camps around country towns. A small number owned farms or lived in cities. Across Australia, there were about 60,000 Indigenous people in 1930.

The Defence Act of 1903 only allowed people of "European origin or descent" to join the military. However, in 1914, about 800 Aboriginal people volunteered to fight in World War I. As the war continued, these rules were relaxed. Many joined by saying they were Māori or Indian. During World War II, after the threat of Japanese invasion, Indigenous enlistment was accepted. Up to 3,000 people of mixed descent served in the military. The Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion and other units were also formed. Another 3,000 civilians worked in labor groups.

Work, Low Pay, and Resistance

Indigenous workers in the north found jobs more easily than in the south. This was because there was no cheap convict labor. However, they were not paid wages and were often treated badly. Many believed white people couldn't work in Northern Australia. Pearl hunting employed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers, though many were forced into it. By the 1880s, diving suits were introduced, reducing Indigenous workers to deckhands. Indigenous people gathered at settlements like Broome (for pearl luggers) or Darwin. In Darwin, Indigenous workers were locked up at night. Most Indigenous workers in North Queensland, the Northern Territory, and the Kimberley worked in the cattle industry.

Wage payment varied by state. In Queensland, wages were paid from 1901. They were set at one-third of white wages in 1911, two-thirds in 1918, and equal in 1930. However, some wages were put into trust accounts, from which they could be stolen. In the Northern Territory, there was no rule to pay a wage. Overall, until World War II, about half of Indigenous stockmen received wages, and these were much lower than white wages.

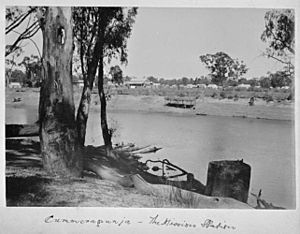

On February 4, 1939, Jack Patten led a strike at Cummeragunja Station in New South Wales. The people of Cummeragunja protested their harsh treatment. A successful farming business was taken from their control, and residents had to live on very small amounts of food. About 200 people left their homes in the Cummeragunja walk-off. Most crossed the border into Victoria and never returned.

During World War II, the Australian Army came to the north. They brought new people and ideas. They employed Indigenous workers in defense projects. These workers were paid wages and mixed with regular troops. This led to an investigation and recommendation to pay wages in the Northern Territory, though it was never enforced. After meetings led by the white communist Don McLeod in 1942, Indigenous groups in Pilbara decided to strike. They did so after the war ended in the 1946 Pilbara strike. In 1949, they finally won a wage double their original demand. They were also encouraged to start their own co-operative based on mining. This event, along with the war, helped reduce the abuse of Indigenous workers.

Racism and Early Civil Rights Efforts

As scientific racism developed, the popular view of Indigenous Australians saw them as inferior. Indigenous Australians were considered the world's most primitive humans by some scientists. This led to trade in human remains and relics. This was especially true for Indigenous Tasmanians. However, in the 1930s, the focus shifted to cultural differences rather than inferiority.

By 1900, most white Australians held racist views of Indigenous peoples. The Constitution of Australia of that year did not count them in the census. Racist treatment was also written into special laws that governed Indigenous peoples separately. Racism also showed up in daily discrimination, called the "colour bar." This affected life in most settled parts of Australia. For example, from the 1890s to 1949, the New South Wales government removed Indigenous children from state schools if non-Indigenous parents objected. They were sent to reserve schools with worse education. The same policy was in Western Australia. Indigenous people were often excluded from organizations, businesses, and sports facilities. Finding employment and housing was difficult for them.

Women's groups became advocates for Indigenous issues in the 1920s. The first Indigenous political organization was the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association, started in 1924. It had 11 branches and over 500 Indigenous members in a year. Other Indigenous organizations included the Australian Aborigines' League in 1934 and the Aborigines Progressive Association in 1937. The latter marked Invasion Day on the 150th anniversary of the First Fleet's landing.

Reserves and Protection Boards

The only known treaty between Indigenous and European Australians was Batman's Treaty. His son, Simon Wonga, and other Kulin nation leaders asked for land in 1859. They were given 1820 hectares by the Victorian government. In 1860, the same government created Aboriginal reserves in places like Coranderrk and Lake Tyers. Corranderrk was very successful, becoming almost self-sufficient. However, the people living there were not given individual land titles or paid wages. In South Australia, Raukkan and Poonindie were also set up for Indigenous peoples. In New South Wales, communities included Maloga and Cummeragunja.

However, the reserve system also gave authorities power over Indigenous people. The Aboriginal Protection Board controlled their work, wages, movement, and child removal in Victoria from 1869. With the Half-Caste Act of 1886, the Victorian government started removing those with partial European ancestry from the reserves. The goal was to "merge the half-caste population into the general community." This also happened in New South Wales. This had bad effects on the communities, leading to their decline. The Queensland Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of * Act of 1897 became a model for other states. It gave authorities power over anyone considered "Aboriginal." This included placing them or their children in reserves, denying voting rights, and banning interracial marriages without permission.

The reserves were mostly reduced, closed, and sold off by the 1920s. Meanwhile, the Protection Boards became more powerful. In 1915, new laws in New South Wales gave them the power to remove children of mixed ancestry without parental or court approval. Later research shows authorities aimed to reunite white families but not Indigenous ones. Overall, Indigenous communities in southeastern Australia came under more government control. They depended on weekly food rations instead of farm work. The 1897 Queensland Act gave reserve superintendents the right to search people, confiscate property, and read mail. They could also expel people to other reserves. Inhabitants had to work 32 hours a week without pay, were verbally abused, and their traditions were forbidden.

Political Activism and Equality (1940s–Present)

World War II brought improvements and new opportunities for Indigenous lives. This was through jobs in the military and war industries. After the war, full employment continued. In 1948, 96% of New South Wales' Indigenous population was employed. Government benefits like Child Endowment and Pensions were expanded to Indigenous people outside reserves during the war. Full inclusion came by 1966. In the 1940s, individuals could apply for freedom from Aboriginal Acts, but conditions were tough. The Nationality and Citizenship Act of 1948 gave citizenship to any Indigenous person born in Australia. In 1949, Indigenous Australians who served in the armed forces or could vote in state elections were given the right to vote in federal elections.

The postwar era also saw more children removed under assimilation policies. Between 1910 and 1970, 10% to 33% of Aboriginal children were taken from their families. The number may have been over 70,000 over 70 years. By 1961, the Aboriginal population had risen to 106,000. This went along with more people moving to cities. By the 1960s, 12,000 lived in Sydney, 5,000 in Brisbane, and 2,000 in Melbourne.

In 1962, the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders began fighting for equal wages. They successfully pressured the Australian Council of Trade Unions to join. As a result, in 1965, the Australian Industrial Relations Commission declared there should be no discrimination in Australian industrial law. However, after this, farmers began using machines and hiring white Australians. By 1971, Indigenous labor had dropped by 30% in some places. Unemployment rose greatly. Indigenous people were pushed off farms and gathered in northern towns.

Indigenous people generally had very poor economic opportunities. In the mid-1960s, 81% of workers were unskilled, 18% semi-skilled, and only 1% skilled in New South Wales. Health differences were huge. Infant mortality rates and child health were much worse, especially in the Northern Territory. Malnutrition, poverty, and poor sanitation affected children's health and school success. In New South Wales, only 4% had finished secondary school or apprentice training.

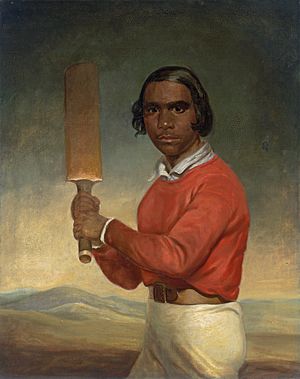

Important Indigenous individuals during this time included activist Douglas Nicholls, artist Albert Namatjira, opera singer Harold Blair, and actor Robert Tudawali. Many Indigenous people were also successful in sports. By 1980, there were 30 national and 5 commonwealth boxing champions. Lionel Rose became world bantamweight champion in 1968. In tennis, Evonne Goolagong Cawley won 11 Grand Slams in the 1970s. Notable players in rugby and Australian rules football included Polly Farmer and Arthur Beetson.

In 1984, a group of Pintupi people living a traditional hunter-gatherer life were found in the Gibson Desert in Western Australia. They were brought to a settlement. They are believed to have been the last uncontacted tribe in Australia.

Activism for Rights

In the 1950s, new political activism for Indigenous rights began. These were "advancement leagues," which were groups of both white and Indigenous people. They included the Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship in Sydney and the Victorian Aborigines Advancement League. A national group, the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, was formed in 1958. Conflicts over power within these groups led to their decline by the 1970s.

After the Sharpeville massacre, racial issues became a bigger part of student politics. An educational assistance program called ABSCHOL was started. In 1965, Charles Perkins organized the Freedom Ride with University of Sydney students. This was inspired by the American Freedom Riders. The reaction from local people was often violent.

Equality Before the Law

In 1961, at the Native Welfare Conference, federal and state ministers agreed on a policy of "assimilation." This included removing unfair laws, improving welfare, education, and training. It also aimed to educate non-Indigenous Australians about Aboriginal culture and history.

All Indigenous Australians were given the right to vote in federal elections by the Menzies government in 1962. The first federal election where all Aboriginal Australians could vote was in November 1963. The right to vote in state elections was granted in Western Australia in 1962. Queensland was the last state to do so in 1965.

The 1967 referendum passed with a 90% majority. This allowed Indigenous Australians to be included in the Commonwealth parliament's power to make special laws for specific races. It also allowed them to be included in counts for electoral representation. This was the largest "yes" vote in Australia's referendum history.

The Office of Aboriginal Affairs was created in 1967 after the referendum. In 1972, it became a separate government department.

Land Rights Movement

The modern land rights movement began with the 1963 Yolngu Bark Petition. Yolngu people from Yirrkala asked the federal government to return their land and rights. The 1966 Wave Hill Walk-Off, or Gurundji Strike, started as a protest about working conditions. It grew into a land rights issue. The people claimed rights to the land, which was a cattle station owned by a British company. The strike lasted eight years.

The Aboriginal Lands Trust Act 1966 (SA) created the South Australian Aboriginal Lands Trust (ALT). This was the first major recognition of Aboriginal land rights by any Australian government. It allowed Aboriginal land held by the SA Government to be given to the ALT. The Trust was run by a Board made up only of Aboriginal people.

In 1971, Justice Richard Blackburn ruled against the Yolngu in the "Gove land rights case." He used the idea of terra nullius (land belonging to no one). This meant he didn't recognize their native title rights. However, Justice Blackburn did acknowledge their traditional use of the land. He also said they had a "subtle and highly elaborate" system of laws. This was the first important legal case for Aboriginal land rights in Australia.

After this case, the Aboriginal Land Rights Commission was set up in the Northern Territory in 1973. This commission recommended recognizing Aboriginal Land Rights. The Whitlam government introduced a bill to Parliament, but it lapsed. The next government, led by Malcolm Fraser, reintroduced a bill. It was signed into law on December 16, 1976.

The Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976 set up how Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory could claim rights to land based on traditional occupation. This law was important because it allowed claims if people could show their traditional connection to the land. Four Land Councils were created under this law. After this, some states introduced their own land rights laws. However, there were often limits on the lands returned or available for claim.

Self-Determination and Recognition

The Australian Aboriginal Flag was designed in 1971 by Harold Thomas, an Aboriginal artist. In 1972, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was set up on the steps of Old Parliament House in Canberra. It demanded sovereignty for Aboriginal Australian peoples. The Tent Embassy asked for land rights and mineral rights to Aboriginal lands. It also asked for legal and political control of the Northern Territory and payment for stolen land.

The National Aboriginal Consultative Committee (NACC) was the first elected body representing Indigenous Australians nationally. It was set up in 1972. It had 36 representatives elected by Aboriginal people. In 1983, about 78% of eligible people voted in these elections. The NACC was later replaced by the National Aboriginal Conference (NAC).

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) was founded in 1989.

The Outstation movement began in the 1970s. It continued through the 1980s. Very small, remote settlements of Aboriginal people were created. People moved from towns and settlements where the government had placed them. This was "a move towards reclaiming autonomy and self-sufficiency." Outstations were created by Aboriginal people who wanted more control over their lives.

Later Debates About History

In 1992, the Australian High Court made a big decision in the Mabo Case. It said the old legal idea of terra nullius (land belonging to no one) was wrong. It recognized the land interests of First Nations people before British settlement. Prime Minister Paul Keating praised the decision. He said it "establishes a fundamental truth, and lays the basis for justice." Native title doctrine was later made into law by the Keating Government in the Native Title Act 1993. This recognition allowed for more legal cases for Indigenous land rights in Australia.

In 1998, a National Sorry Day was started. This was because of the 1997 Bringing Them Home report about the Stolen Generations. This day acknowledged the wrong done to Indigenous families when children were forcibly removed. Many politicians took part. In 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a formal apology for the Stolen Generations.

In 1999, a referendum was held. It asked to change the Australian Constitution to include a preamble. This preamble would recognize Indigenous Australians' occupation of Australia before British Settlement. This referendum was defeated.

In 2004, the Australian Government closed The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC). This had been Australia's main Indigenous organization. The government said there was corruption and misuse of public funds. Indigenous specific programs were then moved to departments that served the general population. Funding was also stopped for remote homelands.

See also

- Australian Aboriginal identity

- Aboriginal reserve

- Aboriginal land rights in Australia

- Aboriginal South Australians

- Aboriginal Tasmanians

- Aboriginal Victorians

- Australian archaeology

- Australian genocide debate

- Bringing them home report (1997)

- Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? (2014 book)

- Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate (2021 book)

- Genocide of indigenous peoples#Colonization of Australia and Tasmania

- History of Indigenous Australian self-determination

- History wars

- List of Aboriginal missions in New South Wales

- List of Indigenous Australian firsts

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- Native title in Australia

- Stolen Generations

- Tasmania#Removal of Aborigines

Images for kids

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |