History of Slovenia facts for kids

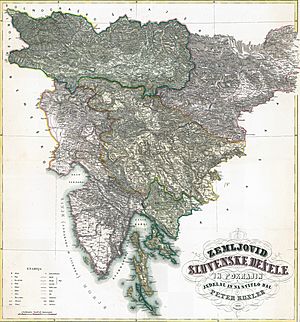

The history of Slovenia tells the story of the land where Slovenia is today, from ancient times to now. Around 2,500 years ago, early tribes lived in this area. Later, it became part of the Roman Empire. During a time of big migrations, many groups moved through the land. Around the late 500s AD, the ancestors of today's Slovenians, called Alpine Slavs, settled here.

For almost 1,000 years, the Holy Roman Empire controlled the land. From the mid-1300s until 1918, most of Slovenia was ruled by the Habsburgs. In 1918, most of Slovenia joined the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. In 1929, a region called the Drava Banovina was created within Yugoslavia, with its capital in Ljubljana. This area mostly matched where Slovenians lived.

After World War II, in 1945, the Socialist Republic of Slovenia was formed as part of federal Yugoslavia. Slovenia became independent from Yugoslavia in June 1991. Today, Slovenia is a member of the European Union and NATO.

Contents

- Early Times to Slavic Arrivals

- Middle Ages

- Early Modern Period

- Enlightenment and National Movement

- National Identity in the Late 1800s

- Emigration

- Joining Yugoslavia and Border Struggles

- Slovenia in Tito's Yugoslavia

- Republic of Slovenia

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Times to Slavic Arrivals

Ancient History

During the last Ice Age, Neanderthals lived in what is now Slovenia. A famous Neanderthal site is the Divje Babe cave, where the Divje Babe flute was found in 1995. Some believe this perforated bone is the oldest musical instrument ever found.

The world's oldest wooden wheel and axle was discovered near the Ljubljana Marsh in 2002.

Later, during the time between the Bronze and Iron Ages, the Urnfield culture thrived here. Many old remains from the Hallstatt period have been found in Slovenia, especially in places like Most na Soči and Vače.

Novo Mesto is a very important archaeological site from the Hallstatt culture. It's called the "City of Situlas" because many ancient situlas (special buckets) were found there.

-

Ljubljana Marshes Wheel, from about 3150 BC

-

Gold decorations from the Urnfield culture, about 1200 BC.

-

Bronze chest plate from the Hallstatt culture, 600 BC

Celts and Romans

In the Iron Age, Illyrian and Celtic tribes lived in Slovenia. Around the 1st century BC, the Romans took over the region. They created provinces like Pannonia and Noricum. Western Slovenia became part of Roman Italy. Important Roman towns here included Emona (Ljubljana), Celeia (Celje), and Poetovio (Ptuj).

During the Migration Period, many groups invaded the region. This was because it was a key route from the Pannonian Plain to Italy. Rome eventually left the area in the late 300s. Many cities were destroyed, and people moved to safer, higher places. In the 400s, the region was part of the Ostrogothic Kingdom.

Slavic Settlement

The Slavic ancestors of today's Slovenes arrived in the Eastern Alps area in the late 500s. They came from two directions: from the North (through today's Austria and Czech Republic) and from the South (through today's Slavonia).

King Samo's Rule

These Slavic tribes, also known as the Alpine Slavs, were under the rule of the Pannonian Avars. In 623 AD, they joined the tribal union led by the Slavic King Samo. After Samo died, the Slavs in Carniola (part of modern Slovenia) again came under Avar rule. However, the Slavs north of the Karavanke mountains formed their own state, called Carantania.

Middle Ages

From Carantania to Carinthia

In 745, Carantania and other Slavic lands in Slovenia were pressured by the Avars. They asked for help from the Bavarians and became part of the Carolingian Empire. The Carantanians and other Slavs in Slovenia also became Christians.

Carantania kept its independence until 818. After a rebellion, the local princes were replaced by German rulers. Under Emperor Arnulf of Carinthia, Carantania briefly became a strong regional power. But it was later destroyed by Hungarian invasions in the late 800s.

In 976, Emperor Otto I created Carinthia as a new duchy within the Holy Roman Empire. However, old Carantania never became a single, unified kingdom.

Between the 1000s and 1300s, new regions called "marks" were formed on the southeastern border of the German Empire. These became the main areas for the development of the historical Slovenian lands: Carniola, Styria, and western Goriška/Gorizia. Powerful families like the Dukes of Spanheim and the Counts of Celje, and finally the House of Habsburg, helped shape these lands.

Slovenes as a Unique Group

People started to think of Slovenes as a distinct group, beyond just their region, in the 1500s.

During the 1300s, most of the Slovene Lands came under Habsburg rule. By the end of the 1400s, most Slovene-speaking areas were part of the Habsburg monarchy. Most Slovenes lived in a region called Inner Austria. They made up most of the population in the Duchy of Carniola and the County of Gorizia and Gradisca, as well as in Lower Styria and southern Carinthia.

Slovenes also lived in the Imperial Free City of Trieste, though they were a minority there.

Early Modern Period

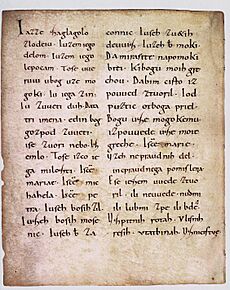

In the 1500s, the Protestant Reformation spread in the Slovene Lands. During this time, the first books in Slovene were written by the Protestant preacher Primož Trubar. This helped create the basis for the standard Slovene language. Many books were printed in Slovene, including a full translation of the Bible.

However, during the Counter-Reformation in the late 1500s and 1600s, most Protestants were forced to leave Slovenia (except for Prekmurje). Still, they left a strong mark on Slovene culture. The old Slovene writing system, called Bohorič's alphabet, was developed by Protestants and used until the mid-1800s.

Between the 1400s and 1600s, the Slovene Lands faced many problems. Many areas, especially in southern Slovenia, were destroyed by wars between the Habsburgs and the Ottoman Empire. Towns like Vipavski Križ were completely ruined by Ottoman attacks. Slovene noblemen played an important role in fighting the Ottomans. Their army defeated the Ottomans in the Battle of Sisak in 1593, ending the immediate threat.

In the 1500s and 1600s, western Slovenia became a battlefield for wars between the Habsburg monarchy and the Venetian Republic. There were also many peasant uprisings, like the Croatian–Slovene Peasant Revolt of 1573 and the Tolmin Peasant Revolt of 1713.

The late 1600s saw a lot of intellectual and artistic activity. Many Italian artists, especially architects and musicians, came to Slovenia. They helped develop the local culture. Scientists like Johann Weikhard von Valvasor also contributed to learning. By the early 1700s, however, the region entered a period of slow growth.

Enlightenment and National Movement

Between the early 1700s and early 1800s, the Slovene lands had a time of peace and some economic recovery. The city of Trieste became a free port in 1718, which helped the economy in western Slovenia. Reforms by Habsburg rulers Maria Theresa of Austria and Joseph II improved life for farmers and helped the growing middle class.

In the late 1700s, people started to standardize the Slovene language. This was promoted by clergymen like Marko Pohlin. At the same time, peasant writers began using and promoting Slovene in the countryside. This movement helped revive Slovene literature. The Age of Enlightenment in the 1700s also strengthened Slovene culture, especially through the Zois Circle. After two centuries of slow progress, Slovene literature grew again, with important works by Anton Tomaž Linhart and Valentin Vodnik. However, German remained the main language for culture, government, and education until the 1800s.

Between 1805 and 1813, the Slovene-settled territory was part of the Illyrian Provinces, a region controlled by Napoleon's First French Empire. Its capital was Ljubljana. Even though French rule was short, it greatly helped Slovenes feel more confident about their national identity and freedoms. The French introduced equality before the law, required military service, and a fair tax system. They also separated government from the Church and modernized the justice system.

In August 1813, Austria declared war on France. Austrian troops invaded the Illyrian Provinces. After this short French period, all Slovene Lands were again part of the Austrian Empire. Slowly, a distinct Slovene national feeling grew, and people wanted to unite all Slovenes politically. In the 1820s and 1840s, interest in Slovene language and folklore grew a lot. Many experts collected folk songs and started to standardize the language.

Some Slovene activists supported the Illyrian movement from neighboring Croatia, which aimed to unite all South Slavic peoples. Ideas of Pan-Slavic unity also became important. However, a group around the expert Matija Čop and the poet France Prešeren argued for Slovene language and culture to remain separate, not merging into a larger Slavic nation.

In 1848, a large political movement for a United Slovenia (Zedinjena Slovenija) began. This was part of the "Spring of Nations" in the Austrian Empire. Slovene activists wanted all Slovene-speaking areas to be united into an independent Slovene kingdom within the Austrian Empire. Although this plan didn't happen, it became the main goal for Slovene political activity for many decades.

National Identity in the Late 1800s

Between 1848 and 1918, many organizations were founded in Slovenia. These included theaters, publishing houses, and political and cultural groups. This period is known as the Slovene National Awakening. Even though they were politically divided, Slovenes managed to build a strong national infrastructure.

When a constitution granting civil and political freedoms was introduced in the Austrian Empire in 1860, the Slovene national movement grew stronger. Slovene nationalists wanted cultural and political independence for the Slovene people. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, large public meetings called tabori were held to support the United Slovenia plan. Thousands of people attended these rallies, showing that many Slovenes wanted national freedom.

By the end of the 1800s, Slovenes had a standardized language and a strong civil society. Many people could read and write, and national associations were active everywhere. The idea of a common country for all South Slavs, called Yugoslavia, also started to emerge.

From the 1880s, a strong "culture war" began in Slovene political life, especially in Carniola. This was between Catholic traditionalists and liberals. At the same time, growing industries led to social tensions. Both Socialist and Christian socialist movements gained support. In 1905, the first Socialist mayor in the Austro-Hungarian Empire was elected in the Slovene mining town of Idrija.

Around 1900, national conflicts in mixed areas (like Carinthia, Trieste, and towns in Lower Styria) became very important. By the 1910s, conflicts between Slovene and Italian speakers, and Slovene and German speakers, became very intense.

In the two decades before World War I, Slovene arts and literature flourished. Important writers included Ivan Cankar and Oton Župančič. Ivan Grohar and Rihard Jakopič were talented visual artists.

After the Ljubljana earthquake of 1895, the city modernized quickly. Architects like Max Fabiani brought their style to Ljubljana. At the same time, the port of Trieste became an important center for Slovene economy and culture. By 1910, about a third of Trieste's population was Slovene, more than in Ljubljana.

Around 1900, hundreds of thousands of Slovenes moved to other countries. Most went to the United States, but also to South America, Germany, and other cities in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It's estimated that one in six Slovenes left their homeland between 1880 and 1910.

Emigration

From the 1880s until World War I, many Slovenes moved to America. The largest group settled in Cleveland, Ohio. The second largest group settled in Chicago. Many Slovene immigrants also went to Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia to work in coal mines and the lumber industry. Some worked in steel mills in Pittsburgh or Youngstown, Ohio, or in iron mines in Minnesota.

During World War I, Slovenia was heavily affected by fighting. Slovene politicians tried to secure a better position for their people within the Habsburg Monarchy. In 1917, Slovene, Croatian, and Serbian politicians in Vienna called for a united South Slavic state. The Habsburg rulers first rejected this. Most Slovenian politicians then started to lean towards full independence.

Joining Yugoslavia and Border Struggles

The Slovene People's Party started a movement for self-determination. They wanted a semi-independent South Slavic state under Habsburg rule. Most Slovene parties supported this idea. A large movement, called the Declaration Movement, followed. By early 1918, over 200,000 signatures were collected in favor of this plan.

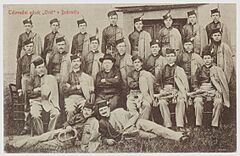

During the war, about 500 Slovenes volunteered for the Serbian army. A smaller group joined the Italian Army. In the last year of the war, many Slovene regiments in the Austro-Hungarian Army rebelled against their leaders. The most famous was the Judenburg Rebellion in May 1918.

After the Austro-Hungarian Empire broke apart at the end of World War I, a National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs took power in Zagreb on October 6, 1918. On October 29, independence was declared in Ljubljana and by the Croatian parliament. This created the new State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. On December 1, 1918, this new state joined with Serbia, becoming the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. In 1929, it was renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Slovenes whose land ended up under Italy, Austria, and Hungary faced policies that tried to make them adopt the culture of those countries.

Border with Austria

After the Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved in late 1918, an armed conflict began between Slovenes and German Austria over the regions of Lower Styria and southern Carinthia. In November 1918, Rudolf Maister took control of Maribor and nearby areas of Lower Styria for the new Yugoslav state. Maribor and Lower Styria were eventually given to Yugoslavia by the Treaty of Saint-Germain.

Around the same time, Slovene volunteers tried to take control of southern Carinthia. Fighting there lasted until June 1919. However, in October 1920, most people in southern Carinthia voted to stay in Austria. Only a small part of the province went to Yugoslavia. On the other hand, the Treaty of Trianon gave Yugoslavia the Slovene-inhabited Prekmurje region, which had been part of Hungary for centuries.

Border with Italy

In exchange for joining the Allied Powers in World War I, the Kingdom of Italy was promised large parts of Austro-Hungarian territory. This was part of the secret Treaty of London (1915). After the war, Italy annexed some of these areas, including about a quarter of the Slovene ethnic territory. This meant about 327,000 Slovenes out of 1.3 million became part of Italy.

Trieste was actually the largest Slovene city at the end of the 1800s, with more Slovene residents than Ljubljana. After Trieste became part of Italy, Italian groups attacked Slovene shops, libraries, and the main Slovene cultural center, Narodni dom. This was followed by forced Italianization. By the mid-1930s, thousands of Slovenes, especially educated people from the Trieste region, moved to Yugoslavia or South America.

The Slovenian areas of Idrija, Ajdovščina, Vipava, Kanal, Postojna, Pivka, and Ilirska Bistrica were also forced to adopt Italian culture. The Slovene minority in Italy had no protection under international law. Clashes between Italian authorities and Fascist groups on one side, and local Slovenes on the other, began as early as 1920. This led to the burning of the Narodni dom in Trieste. After all Slovene minority groups in Italy were shut down, the anti-Fascist group TIGR was formed in 1927 to fight Fascist violence.

In March 1941, Yugoslavia signed a treaty with Germany. Two days later, a coup led by General Dušan Simović took over the government. This made Hitler see Yugoslavia as unreliable. So, on April 6, 1941, Axis forces invaded Yugoslavia. The attack began with the bombing of Belgrade. The Yugoslav army's resistance was weak. German troops reached Zagreb by April 10 and Belgrade by April 12. The Italian army attacked on April 11.

After Yugoslavia surrendered, Hungary took most of Prekmurje. Italy initially had a moderate policy in its occupied territory, allowing bilingualism and cultural groups. They established the Province of Ljubljana. However, after the first rebel actions, Italian authorities changed their policy. They began a program of ethnic cleansing, expelling about 35,000 civilians. Around 3,500 people died in Italian concentration camps in 1942 and 1943 from hunger and disease.

The German occupation was very harsh. They banned all Slovenian newspapers and introduced German in schools. Adults were forced to join Nazi organizations. They took away 600 children who seemed to fit the "Aryan race" criteria and assigned them to the Lebensborn organization. They also introduced Nazi laws and later forced people into military service, which was against international law.

On April 26, 1941, the Anti-Imperialist Front (later renamed the Liberation Front) was formed in Ljubljana. It began an armed struggle against the occupiers. Its founding groups included the Communist Party of Slovenia and parts of Christian Socialists and liberals. April 27 is now celebrated as the day of resistance against the occupier.

In 1943, a liberated area was formed in Kočevje. There, the Liberation Front organized a meeting where they elected the highest body of the Slovenian state. They also decided to join the Primorska Slovenia region and elected a delegation for a major Yugoslav meeting.

At the end of the war, the Slovene Partisan army, along with the Yugoslav Army and the Soviet Red Army, freed all of Slovenia.

Slovenia in Tito's Yugoslavia

After World War II, Yugoslavia was re-established, and Slovenia became part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, declared on November 29, 1943. A socialist state was set up. Because of the Tito–Stalin split, people in Yugoslavia had more economic and personal freedoms than in other Eastern Bloc countries. In 1947, Italy gave most of the Julian March to Yugoslavia, and Slovenia got back the Slovenian Littoral. Many Italians living in towns like Koper moved away due to fear of Communism and past conflicts.

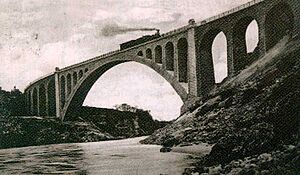

The disagreement over the port of Trieste continued until 1954. Then, the Free Territory of Trieste was divided between Italy and Yugoslavia, giving Slovenia access to the sea. This division was made final in 1975 with the Treaty of Osimo. From the 1950s, the Socialist Republic of Slovenia had a good amount of self-rule.

Stalinist Period

Between 1945 and 1948, many people were arrested in Slovenia and Yugoslavia for their political beliefs. Thousands were imprisoned. Tens of thousands of Slovenes left Slovenia right after the war, fearing Communist persecution. Many settled in Argentina, forming the core of anti-Communist Slovene communities abroad. More than 50,000 more left in the next decade, often for economic reasons. These later immigrants mostly settled in Canada and Australia.

The Tito–Stalin Split

In 1948, the Tito–Stalin split happened. In the years after, political repression got worse, even for Communists accused of supporting Stalin. Hundreds of Slovenes were sent to the Goli Otok concentration camp. Important trials took place, like the Nagode Trial against democratic thinkers (1946) and the Dachau trials (1947–1949), where former Nazi camp prisoners were accused of working with the Nazis. Many Catholic clergy were also persecuted.

1950s: Industrial Growth

In the late 1950s, Slovenia was the first Yugoslav republic to start becoming more open. A decade of industrialisation brought a lot of cultural and literary work, often with tension between the government and writers who disagreed with it. From the late 1950s, groups of people who disagreed with the government started to form, often around independent journals.

1960s: "Self-management"

By the late 1960s, a reformist group took control of the Slovenian Communist Party. They started reforms to modernize Slovene society and economy. A new economic policy, called workers self-management, began to be put in place.

1970s-1980s: "Years of Lead"

In 1973, this reform trend was stopped by the conservative part of the Slovenian Communist Party, supported by the Yugoslav government. This period was known as the "Years of Lead." During this time, censorship and repression of the press and artists increased, and freedom of speech decreased. Many people were jailed for their political views.

1980s: Towards Independence

In the 1980s, Slovenia saw a rise in cultural diversity. Many political, artistic, and intellectual movements emerged. By the mid-1980s, a reformist group led by Milan Kučan took control of the Slovenian Communist Party. They started a gradual reform towards more political openness.

Yugoslavia's economic problems in the 1980s increased disagreements within the Communist government about how to fix the economy. Slovenia, with less than 10% of Yugoslavia's population, produced about a fifth of the country's GDP. Many Slovenes felt they were being economically used to support an expensive federal government.

In 1987 and 1988, clashes between the growing civil society and the Communist government led to the Slovene Spring. In 1987, a group of liberal thinkers published a manifesto calling for democracy and greater independence for Slovenia. Some articles openly discussed Slovenia leaving Yugoslavia and becoming a full democracy. The government condemned the manifesto, but the authors were not directly punished.

Later in 1988, the Yugoslav Army arrested four Slovenian journalists. This led to large protests in Ljubljana and other Slovenian cities. A mass democratic movement pushed the Communists towards democratic reforms. These events in Slovenia happened almost a year before the Revolutions of 1989 in Eastern Europe.

At the same time, the conflict between the Slovenian and Serbian Communist Parties became the main political struggle in Yugoslavia. The poor economy and growing clashes between republics made many Slovenes, both anti-Communists and Communists, think about leaving Yugoslavia. On September 27, 1989, the Slovenian Assembly changed the constitution. It ended the Communist Party's monopoly on power and confirmed Slovenia's right to leave Yugoslavia.

In 1989, Slovene police forces prevented hundreds of supporters of the Serbian nationalist leader Slobodan Milošević from meeting in Ljubljana. This action, called "Action North," was an attempt to overthrow Slovenian leaders. It is seen as the first defense action for Slovenian independence.

On January 23, 1990, the League of Communists of Slovenia walked out of the 14th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia in protest against Serbian nationalist control. This effectively ended the League of Communists of Yugoslavia as a national party.

In September 1989, the Assembly passed many changes to the constitution, introducing parliamentary democracy to Slovenia. On March 7, 1990, the Assembly changed the official name of the state to the Republic of Slovenia, dropping the word 'Socialist'. The new name became official on March 8, 1990.

Republic of Slovenia

Free Elections

On December 30, 1989, Slovenia officially allowed opposition parties to run in the spring 1990 elections, starting multi-party democracy. The Democratic Opposition of Slovenia (DEMOS) was a group of democratic political parties. Its leader was the well-known dissident Jože Pučnik.

On April 8, 1990, the first free multiparty parliamentary elections were held. DEMOS won, getting 54% of the votes. A government led by the Christian Democrat Lojze Peterle was formed. This government began economic and political reforms to create a market economy and a democratic system. At the same time, the government worked towards Slovenia's independence from Yugoslavia.

Milan Kučan was elected president in the second round of the presidential elections on April 22, 1990.

Kučan's Presidency (1990–2002)

The DEMOS Government (1990–1992): Independence

Milan Kučan was strongly against keeping Yugoslavia together by force. When the idea of a loose confederation failed, Kučan supported a peaceful process for Slovenia to leave Yugoslavia. This would allow former Yugoslav nations to work together in a new way.

On December 23, 1990, a referendum on Slovenia's independence was held. More than 88% of Slovenians voted for independence from Yugoslavia. Slovenia became independent on June 25, 1991. The next morning, a short Ten-Day War began. Slovenian forces successfully fought off Yugoslav military interference. That evening, independence was officially declared in Ljubljana. The Ten-Day War lasted until July 7, 1991, when the Brijuni Agreement was made. The European Community helped mediate this agreement, and the Yugoslav National Army began to leave Slovenia. On October 26, 1991, the last Yugoslav soldier left Slovenia.

On December 23, 1991, the Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia passed a new Constitution, which was the first for independent Slovenia.

Kučan represented Slovenia at peace conferences about former Yugoslavia. On May 22, 1992, Kučan represented Slovenia as it became a new member of the United Nations.

The most important achievement of the DEMOS coalition was declaring Slovenia's independence on June 25, 1991. This was followed by the Ten-Day War, where Slovenes resisted Yugoslav military action.

Due to internal disagreements, the DEMOS coalition broke apart in 1992. After Lojze Peterle's government fell, a new government led by Janez Drnovšek was formed. Jože Pučnik became vice-president in Drnovšek's government, ensuring some continuity.

Croatia was the first country to recognize Slovenia as independent on June 26, 1991. In late 1991, some countries formed after the collapse of the Soviet Union also recognized Slovenia. On December 19, 1991, Iceland and Sweden recognized Slovenia. Germany passed a resolution to recognize Slovenia, which happened along with the European Economic Community (EEC) on January 15, 1992. The Holy See and San Marino recognized Slovenia on January 13 and 14, 1992. Canada and Australia were the first overseas countries to recognize Slovenia on January 15 and 16, 1992. The United States was hesitant at first and recognized Slovenia only on April 7, 1992.

The recognition by the EEC was very important. In December 1991, the EEC set criteria for recognizing new countries, including democracy, respect for human rights, the rule of law, and respect for national minority rights. Slovenia's recognition meant it met these criteria.

In December 1992, after independence, Kučan was elected as the first president of Slovenia. He won another five-year term in 1997.

Drnovšek's Time as Prime Minister (1992–2002): New Trade Focus

Drnovšek was the second Prime Minister of independent Slovenia. He was chosen as a compromise candidate and an expert in economic policy. Drnovšek's governments shifted Slovenia's trade away from Yugoslavia and towards the West. Unlike some other former Communist countries, Slovenia's economic changes happened gradually. After a short time out of power in 2000, Drnovšek returned and helped arrange the first meeting between George W. Bush and Vladimir Putin in 2001.

Drnovšek's Presidency (2002–2007); EU and NATO Membership

Drnovšek served as president from 2002 to 2007. During his term, in March 2003, Slovenia held two referendums on joining the EU and NATO. Slovenia joined NATO on March 29, 2004, and the European Union on May 1, 2004. On January 1, 2007, Slovenia joined the Eurozone and adopted the euro as its currency.

Janša's First Term as Prime Minister (2004–2008)

Janez Janša was Prime Minister from November 2004 to November 2008. During this time, after joining the EU, Slovenian banks borrowed too much from foreign banks and then lent too much to the private sector. This led to unsustainable growth.

Türk's Presidency (2007–2012)

Danilo Türk was president from 2007 to 2012.

Pahor's First Term as Prime Minister (2008–2012)

Borut Pahor was Prime Minister from November 2008 until February 2012. His government faced the global economic crisis. He proposed economic reforms, but they were rejected by the opposition and blocked by referendums in 2011. However, voters approved an agreement with Croatia to solve their border dispute. In 2010, Slovenia joined the OECD.

Pahor's Presidency (2012-2022)

Pahor has been president since 2012. In November 2017, Borut Pahor was re-elected for a second term.

Janša's Second Term as Prime Minister (2012–2013)

Janša was Prime Minister from February 2012 until March 2013. He was replaced by the first female Prime Minister in Slovenia's history, Alenka Bratušek. This happened after an anti-corruption report was released.

Miro Cerar was prime minister from September 2014 until March 2018. His government included his own party, the Social Democrats, and a pensioners’ party.

In June 2018, the center-right Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) of former prime minister Janez Janša won the election. In August 2018, Marjan Šarec formed a minority government. In January 2020, Prime Minister Šarec resigned because his government was too weak.

Janša's Third Term as Prime Minister (2020-2022)

In March 2020, Janez Janša became prime minister for the third time in a new coalition government. Janša was known as a right-wing populist.

Golob's Premiership (2022-)

In April 2022, the liberal opposition party, The Freedom Movement, won the parliamentary election. On May 25, 2022, Slovenia’s parliament voted to appoint the leader of Freedom Movement, Robert Golob, as the new Prime Minister of Slovenia.

In November 2022, Nataša Pirc Musar, a liberal candidate and lawyer, won the presidential election. She became Slovenia's first female president.

Pirc Musar's Presidency (2022-)

On December 23, 2022, Nataša Pirc Musar became Slovenia’s fifth president.

Images for kids

-

Ljubljana Marshes Wheel, from about 3150 BC

-

Gold decorations from the Urnfield culture, about 1200 BC.

-

Bronze chest plate from the Hallstatt culture, 600 BC

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Eslovenia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Eslovenia para niños

- Breakup of Yugoslavia

- Divje Babe flute

- Habsburg monarchy

- History of Europe

- History of Austria, History of Italy, History of Hungary, History of Croatia, History of Yugoslavia

- List of presidents of Slovenia

- Prime Minister of Slovenia

- Ten-Day War

- Timeline of Slovenian history

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |