History of Zambia facts for kids

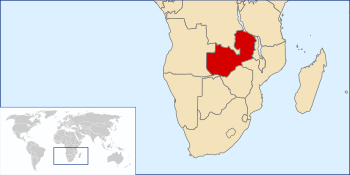

The history of Zambia covers many important stages, from when it was a colony to becoming an independent country on 24 October 1964.

The area we now call Zambia was known as Northern Rhodesia and became a British sphere of influence in 1888. It was officially declared a British protectorate in 1924. After many discussions about joining forces, Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland were combined to form the British Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

In 1960, the British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, announced that the time for colonial rule in Africa was ending. Finally, in December 1963, the federation broke apart. The Republic of Zambia was then formed from Northern Rhodesia on 23 October 1964.

Contents

Zambia's Ancient History

Early Humans in Zambia

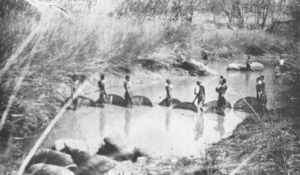

Scientists have found tools and other signs of human life in the Zambezi Valley and at Kalambo Falls. These discoveries show that different groups of people lived here over a very long time. Some ancient camping tools near Kalambo Falls are more than 36,000 years old!

Even older, the fossil skull of Broken Hill Man was found here. This skull is between 125,000 and 300,000 years old. It proves that early humans lived in this area a very long time ago.

The First People: Khoisan and Batwa

The land that is now Zambia was home to the Khoisan and Batwa people. They lived here until about 300 AD. Around that time, Bantu-speaking people started moving into these areas.

The Khoisan people are thought to have come from East Africa. They spread south about 150,000 years ago. The Twa people were divided into two main groups. The Kafwe Twa lived near the Kafue Flats, and the Lukanga Twa lived around the Lukanga Swamp.

Many old rock paintings in Zambia, like the Mwela Rock Paintings, Mumbwa Caves, and Nachikufu Cave, were made by these early hunter-gatherer groups. The Khoisan and Twa people often worked with the farming Bantu groups. Eventually, they either moved away or joined the Bantu groups.

The Bantu People Arrive

The Bantu people, also called Abantu (meaning "people"), are a very large and diverse group. They make up most of the population in many parts of East, Southern, and Central Africa. Zambia is located where Central, Southern, and the African Great Lakes regions meet. Because of this, Zambia's history is closely linked to the history of these three regions.

Many historical events in these areas happened at the same time. So, Zambia's history, like many African nations, can't always be told in perfect order. What we know about the early history of the people in modern Zambia comes from spoken stories, archaeological finds, and written records, mostly from non-Africans.

Where Did the Bantu Come From?

The Bantu people originally lived in West/Central Africa, in the area that is now Cameroon and Nigeria. About 4,000 to 3,000 years ago, they began a huge movement across much of the continent. This event is called the Bantu Expansion. It was one of the largest human migrations in history.

The Bantu are believed to be the first people to bring iron working technology to large parts of Africa. The Bantu Expansion mainly followed two paths. One went west through the Congo Basin, and the other went east through the African Great Lakes.

First Bantu Communities in Zambia

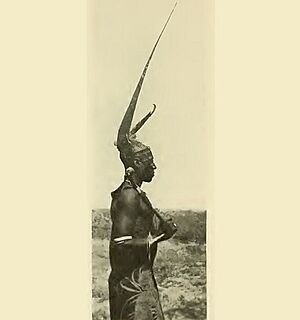

The first Bantu people to arrive in Zambia came through the eastern route, passing by the African Great Lakes. They arrived around 1000 AD. Among them were the Tonga people (also called Ba-Tonga, "Ba-" means "men") and the Ba-Ila. These groups settled in Southern Zambia, near Zimbabwe. According to Ba-Tonga oral stories, they came from the east, near a "big sea."

Later, the Ba-Tumbuka joined them. They settled in Eastern Zambia and Malawi.

These early Bantu people lived in large villages. They didn't have one main chief but worked together as a community. They helped each other prepare their fields for crops. Villages often moved because the soil would become tired from using the slash-and-burn farming method. They also kept many cattle, which were a very important part of their lives.

The first Bantu communities in Zambia were very self-sufficient. Many people who met them were impressed by how independent they were. Early European missionaries who settled in Southern Zambia also noticed this independence. One missionary wrote:

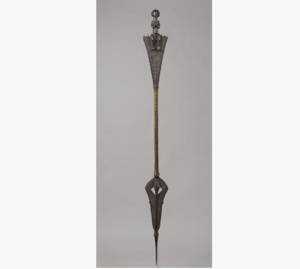

"If weapons for war, hunting, and domestic purposes are needed, the [Tonga] man goes to the hills and digs until he finds the iron ore. He smelts it and with the iron thus obtained makes axes, hoes, and other useful implements. He burns wood and makes charcoal for his forge. His bellows are made from the skins of animals and the pipes are clay tile, and the anvil and hammers are also pieces of the iron he has obtained. He moulds, welds, shapes, and performs all the work of the ordinary blacksmith."

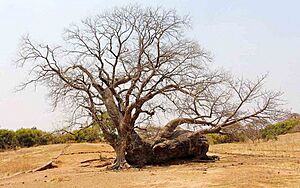

These early Bantu settlers also took part in trade at a place called Ingombe Ilede. This name means "sleeping cow" in Chi-Tonga, because a fallen baobab tree there looked like a cow. At this trading site in Southern Zambia, they met many Kalanga/Shona traders from Great Zimbabwe and Swahili traders from the East African Swahili Coast. Ingombe Ilede was a very important trading post for the rulers of Great Zimbabwe.

Goods traded at Ingombe Ilede included fabrics, beads, gold, and bangles. Some of these items came from what is now the southern Democratic Republic of Congo and Kilwa Kisiwani. Others came from as far away as India, China, and the Arab World. Portuguese traders joined the African traders in the 16th century.

The decline of Great Zimbabwe, due to more trade competition from other Kalanga/Shona kingdoms like Khami and Mutapa, led to the end of Ingombe Ilede.

Second Bantu Communities in Zambia

The second large group of Bantu people to settle in Zambia are believed to have come through the western route of the Bantu migration, through the Congo Basin. These Bantu people lived for a long time in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They are the ancestors of most modern Zambians.

There is some information that the Bemba people have an old connection to the Kingdom of Kongo through a BaKongo ruler. However, this information is not fully proven.

Luba-Lunda Kingdoms

The Bemba people, along with other related groups like the Lamba, Bisa, Senga, Kaonde, Swaka, Nkoya and Soli, were important parts of the Kingdom of Luba in the Upemba area of the Democratic Republic of Congo. They have strong ties to the BaLuba people. The area where the Luba Kingdom was located has been home to early farmers and iron-workers since the 300s AD. Over time, these communities learned to use nets, harpoons, make dugout canoes, clear canals through swamps, and build dams as high as 2.5 meters.

Because of these skills, they developed a diverse economy. They traded fish, copper, iron items, and salt for goods from other parts of Africa, like the Swahili Coast, and later, from the Portuguese. From these communities, the Kingdom of Luba grew in the 14th century.

The Luba Kingdom was a large kingdom with a centralized government and smaller independent chiefdoms. It had large trading networks that connected the forests in the Congo Basin and the mineral-rich plateaus of what is now Copperbelt Province. These networks stretched from the Atlantic Coast to the Indian Ocean Coast. Art was also highly valued in the kingdom, and skilled artists were respected.

The Kingdom of Luba also had well-developed literature.

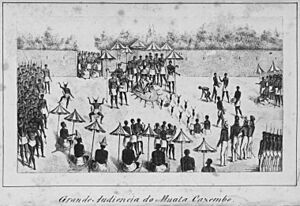

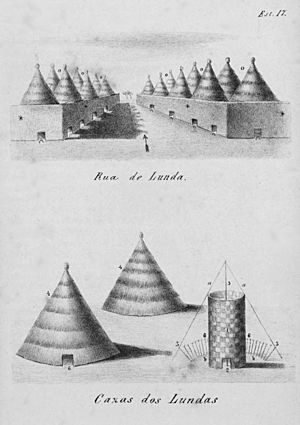

In the same region of Southern Congo, the Lunda people became connected to the Kingdom of Luba and adopted parts of Luba culture and government. This led to the creation of the Kingdom of Lunda to the south. According to Lunda origin stories, a Luba hunter named Chibinda Ilunga married a local Lunda princess around 1600. He brought the Luba way of governing to the Lunda.

The Lunda, like the Luba, also traded with both the Atlantic and Indian Ocean coasts. Under ruler Mwaant Yaav Naweej, trade routes to the Atlantic coast were set up. They also had direct contact with European traders who wanted slaves and forest products. The Lunda controlled the regional copper trade, and settlements around Lake Mweru managed trade from the East African coast.

The Luba-Lunda kingdoms eventually weakened. This was due to the slave trade from both the west (Atlantic) and east (Indian Ocean), and wars with groups that broke away from the kingdoms. The Chokwe, a group related to the Luvale, were initially affected by the demand for slaves. But once they broke away from the Lunda State, they became powerful and were involved in the slave trade. The Chokwe were later defeated by other ethnic groups and the Portuguese.

This period of instability led to the collapse of the Luba-Lunda kingdoms. Many people moved into different parts of Zambia from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Most Zambians today can trace their family history back to the Luba-Lunda and surrounding Central African states.

The Maravi Confederacy In the 1200s, before the Luba-Lunda kingdoms were founded, a group of Bantu people started moving from the Congo Basin to Lake Mweru. They eventually settled around Lake Malawi. These migrants are thought to have been some of the people living in the Upemba Depression area in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. By the 1400s, these groups, known as the Maravi, with the Chewa people being the most prominent, began to include other Bantu groups like the Tumbuka.

In 1480, the Maravi Empire was founded by the Kalonga, who was the main chief of the Maravi. He was from the Phiri clan, one of the main clans along with Banda, Mwale, and Nkhoma. The Maravi Empire stretched from the Indian Ocean through what is now Mozambique to Zambia and large parts of Malawi. The way the Maravi were organized politically was similar to the Kingdom of Luba, and it's believed to have come from there. The main export of the Maravi was ivory, which was traded to Swahili merchants.

In the 1590s, the Portuguese tried to control the Maravi's export trade. The Maravi of Lundu reacted strongly, sending their WaZimba armed forces. The WaZimba attacked and took over the Portuguese trading towns of Tete, Sena, and other towns.

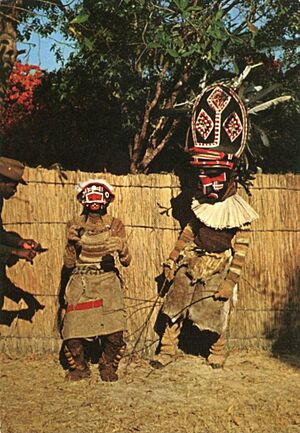

The Maravi are also believed to have brought the traditions that would become the Nyau secret society from the Upemba Depression. The Nyau form the spiritual beliefs or traditional religion of the Maravi people. The Nyau society involves special dance performances and masks used for the dances. This belief system spread throughout the region.

The Maravi Empire began to decline due to disagreements over who should rule, attacks by the Ngoni, and slave raids from the Yao.

Mutapa Empire & Mfecane

As Great Zimbabwe was weakening, one of its princes, Nyatsimba Mutota, left and formed a new empire called Mutapa. He and later rulers were given the title Mwene Mutapa, which means "Ravager of the Lands."

The Mutapa Empire ruled land between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers. This area is now part of Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique. It existed from the 14th to the 17th century. At its strongest, Mutapa had conquered the Dande area of the Tonga and Tavara people. The Mutapa Empire mainly traded across the Indian Ocean with and through the WaSwahili. They mostly exported gold and ivory in exchange for silk and ceramics from Asia.

Like the Maravi at the time, Mutapa had problems with the arriving Portuguese traders. This difficult relationship became worse when the Portuguese tried to interfere in the kingdom's internal matters. They set up markets and tried to convert people to Christianity. This angered the Muslim WaSwahili living in the capital. This chaos gave the Portuguese an excuse to attack the kingdom and try to control its gold mines and ivory routes. This attack failed when the Portuguese became sick along the Zambezi river.

In the 1600s, internal disagreements and civil war led to the decline of Mutapa. The weakened kingdom was eventually conquered by the Portuguese and later taken over by rival Shona states.

Some historians believe that the presence of early Europeans involved in the slave trade and their attempts to control resources in different parts of Bantu-speaking Africa led to the people in the region becoming more militarized. You can see this with the Maravi's WaZimba warriors. After defeating the Portuguese, they remained quite warlike.

The Portuguese presence was also a big reason for the creation of the Rozvi Empire, a state that broke away from Mutapa. The ruler of the Rozvi, Changamire Dombo, became one of the most powerful leaders in South-Central Africa's history. Under his leadership, the Rozvi defeated the Portuguese and forced them out of their trading posts along the Zambezi river.

Perhaps the most famous example of this increased militarization was the rise of the Zulu under Shaka. Pressure from the English colonialists in the Cape and the Zulu becoming more militarized led to the Mfecane (meaning "the crushing"). The Zulu expanded by taking in the women and children of the tribes they defeated. If the men of these Nguni tribes escaped, they used Zulu military tactics to attack other groups.

This caused huge movements of people, wars, and raids across Southern, Central, and Eastern Africa as Nguni or Ngoni tribes moved through the region. This period is known as the Mfecane. The arriving Nguni under Zwagendaba crossed the Zambezi river, moving north. The Ngoni delivered the final blow to the already weakened Maravi Empire. Many Nguni eventually settled in what is now Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, and Tanzania, blending in with neighboring tribes.

In the western part of Zambia, another Southern African group called the Kololo, who were of Sotho-Tswana heritage, managed to conquer the local people. These locals were migrants from the fallen Kingdom of Luba and Kingdom of Lunda states, called the Luyana or Aluyi. The Luyana had established the Barotse Kingdom on the floodplains of the Zambezi when they arrived from Katanga. Under the Kololo, the Kololo language was forced upon the Luyana. Eventually, the Luyana revolted and overthrew the Kololo. By this time, the Luyana language was mostly forgotten, and a new mixed language, SiLozi, emerged. The Luyana began to call themselves Lozi.

By the end of the 18th century, some of the Mbunda moved to Barotseland, Mongu. The Aluyi and their leader, the Litunga Mulambwa, especially valued the Mbunda for their fighting skills.

By the late 19th century, most of the different peoples of Zambia had settled in the areas where they live today.

Colonial Period in Zambia

In 1888, Cecil Rhodes was working to expand British business and political interests in Central Africa. He obtained agreements from local chiefs to mine for minerals. In the same year, Northern and Southern Rhodesia, which are now Zambia and Zimbabwe, were declared British areas of influence. At first, the territory was managed by Rhodes' British South Africa Company (BSAC). The company didn't show much interest in the area, mainly using it as a source of workers.

The most important part of the colony's economy was copper. Its discovery was partly thanks to an American scout, Frederick Russell Burnham. In 1895, he led a large expedition that confirmed major copper deposits existed in Central Africa. Along the Kafue River in Northern Rhodesia, Burnham noticed many similarities to copper deposits he had seen in the United States. He also met local people wearing copper bracelets.

In 1923, the British government decided not to renew the company's special permission to rule. As a result, Southern Rhodesia was officially taken over and given self-government in 1923. After talks, the administration of Northern Rhodesia was given to the British Colonial Office in 1924 as a protectorate. Livingstone was the capital at first. The capital was moved to the more central Lusaka in 1935. A Legislative Council was created. Five members were elected by the small European minority (only 4,000 people), but no African people were elected.

In 1928, huge copper deposits were found in the region that became known as the Copperbelt. This changed Northern Rhodesia from a potential farming land for white settlers to a major copper exporter. By 1938, the country produced 13% of the world's copper. Two companies developed this industry: the Anglo American Corporation (AAC) and the South African Rhodesian Selection Trust (RST). They controlled the copper sector until Zambia became independent.

Poor safety conditions and higher taxes led to a strike by African mineworkers in 1935, known as the Copperbelt strike. The authorities stopped the strike, and six miners were killed.

During the Second World War, white miners went on strike in 1940. They knew how important their products were for the war and demanded higher salaries. This strike was followed by another one by African mine workers.

Even before the war, there were talks about joining the two Rhodesias. However, the British authorities stopped this process, and the war brought it to a complete halt. Finally, in 1953, both Rhodesias joined with Nyasaland (now Malawi) to form the Central African Federation. Northern Rhodesia was at the center of many problems and crises that affected the federation in its final years. The main issues were strong African demands for more involvement in government and European fears of losing political control.

An election held in two stages in October and December 1962 resulted in an African majority in the legislative council. This led to a difficult partnership between the two African nationalist parties. The council passed resolutions asking for Northern Rhodesia to leave the federation. They also demanded full self-government under a new constitution and a new national assembly based on a wider, more democratic voting system. On 31 December 1963, the federation was dissolved. Northern Rhodesia became the Republic of Zambia on 24 October 1964.

Zambia's Independence

When Zambia became independent, it faced big challenges despite its rich mineral wealth. Inside the country, there were few trained and educated Zambians who could run the government. The economy relied heavily on foreign experts. Most of Zambia's neighboring countries were still colonies or ruled by white minority governments.

The United National Independence Party (UNIP) won the elections before independence. They gained 55 out of 75 seats. The Zambian African National Congress won 10 seats, and the National Progressive Party won all 10 seats reserved for white people. Kenneth Kaunda was elected Prime Minister. Later that same year, he became president as the country adopted a presidential system.

Kaunda adopted an ideology called African socialism, which was similar to what Julius Nyerere followed in Tanzania. Economic policies focused on central planning and nationalisation, where the government took control of private companies. A system of one party rule was also put in place.

Moving Towards One-Party Rule

Quick facts for kids

Republic of Zambia

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Anthem: Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika (1964–1973)

Stand and Sing of Zambia, Proud and Free (1973–1991) |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Lusaka | ||||||||

| Official languages | English | ||||||||

| Religion | Christianity | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Zambian | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary one-party socialist republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1964 - 1991

|

Kenneth Kaunda | ||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||

|

• 1964–1967

|

Reuben Kamanga | ||||||||

|

• 1967–1970

|

Simon Kapwepwe | ||||||||

|

• 1970–1973

|

Mainza Chona | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

|

• 1973–1975

|

Mainza Chona | ||||||||

|

• 1975–1977

|

Elijah Mudenda | ||||||||

|

• 1977–1978

|

Mainza Chona | ||||||||

|

• 1978–1981

|

Daniel Lisulo | ||||||||

|

• 1981–1985

|

Nalumino Mundia | ||||||||

|

• 1985–1989

|

Kebby Musokotwane | ||||||||

|

• 1989–1991

|

Malimba Masheke | ||||||||

| Establishment | |||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

| 24 October 1964 | |||||||||

|

• End of One-Party Rule

|

1991 | ||||||||

| Currency | Zambian kwacha | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | ZM | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

In 1968, Kaunda was re-elected as president. Over the next few years, Zambia became a one-party system. By 1972, all political parties except UNIP were banned. This was made official in a new constitution adopted in 1973. The constitution created a system called "one-party participatory democracy." In reality, this meant UNIP was the only political party in the country.

The system had a strong president and a single-chamber National Assembly. National policies were decided by UNIP's Central Committee. The cabinet then carried out these policies. In elections for the legislature, only candidates from UNIP were allowed to run. Even though there was no competition between parties, there was strong competition for seats within UNIP. For presidential elections, the only candidate allowed was the one chosen as UNIP's president. This way, Kaunda was re-elected without opposition in 1973, 1978, 1983, and 1988.

However, not everyone agreed with the one-party rule, even within UNIP. Sylvester Mwamba Chisembele, who was a Cabinet Minister, and other UNIP leaders formed a "Committee of 14." Their goal was to create a democratically elected council to rule the country with the President as Head of State. This would have limited President Kaunda's absolute power. President Kaunda met with the committee and said he would consider their ideas. However, he later banned the committee, and several leaders, including Sylvester Chisembele, were removed from their positions.

Later, Chisembele rejoined the Cabinet. Other political leaders, like Simon M. Kapwepwe and Harry Mwaanga Nkumbula, tried to challenge President Kaunda for the presidency within UNIP. But they were prevented from doing so by President Kaunda's actions, allowing him to run unopposed. They challenged the 1978 election results in court, but their efforts were unsuccessful.

Economy and the Copper Crisis

After independence, Zambia adopted economic policies that leaned towards the left. The economy was partly managed by central planning through five-year plans. Private companies were taken over by the government and became large state-owned businesses. The government wanted Zambia to be self-sufficient, which they tried to achieve by producing goods themselves instead of importing them. At first, this plan worked, and the economy grew steadily. However, in the mid-1970s, the economy began to decline sharply. Between 1975 and 1990, Zambia's economy shrunk by about 30%.

To deal with this crisis, Zambia borrowed large amounts of money from the International Monetary Fund and the Worldbank. They hoped that copper prices would rise again soon, instead of making big changes to their economic system.

Zambia's Foreign Policy

Internationally, Zambia supported groups that were against colonial rule or white-dominated governments. For example, Zambia actively supported movements like the National Unions for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) during Angola's independence war and later civil war. They also supported the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) in Southern Rhodesia and the African National Congress (ANC) in their fight against apartheid in South Africa. Additionally, they supported the South-West Africa People's Organization (SWAPO) in their struggle for independence for Namibia.

Zambia also hosted some of these movements. For instance, the ANC's main office for exiles was in Lusaka, and ZAPU had a military base in Zambia. This led to security problems for Zambia, as South Africa and Southern Rhodesia attacked targets inside Zambia several times.

Rhodesian military operations extended into Zambia after rebels shot down two unarmed civilian airplanes with Soviet-supplied missiles. In response to one of these incidents in September 1978, the Rhodesian Air Force attacked a rebel base near Lusaka in October 1978. They warned Zambian forces by radio not to interfere.

Conflicts with Rhodesia led to Zambia closing its borders with that country. This caused serious problems with international transportation and power supply. However, the Kariba hydroelectric power station on the Zambezi River provided enough electricity for the country's needs. The TAZARA railway, built with help from China, connected Zambia to the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam. This reduced Zambia's reliance on the railway line south to South Africa and west through Angola, which was experiencing war.

Civil unrest in neighboring Mozambique and Angola created many refugees, and many of them fled to Zambia.

Internationally, Zambia was an active member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), a group of countries that did not formally align with or against any major power bloc during the Cold War. Zambia hosted a NAM summit in Lusaka in 1970. Kenneth Kaunda served as the movement's chairman from 1970 to 1973. Among the NAM countries, Zambia was especially close to Yugoslavia. Outside the NAM, Zambia also had close relations with the People's Republic of China.

In the Second Congo War, Zambia supported Zimbabwe and Congo but did not actively participate in the fighting.

Multi-Party Democracy in Zambia

The End of One-Party Rule

One-party rule and the struggling economy led to widespread disappointment among the people. Several strikes occurred in the country in 1981. The government responded by arresting several union leaders, including Frederick Chiluba. In 1986 and 1987, protests erupted again in Lusaka and the Copperbelt. These were followed by riots over rising food prices in 1990, where at least 30 people were killed. The same year, the state-owned radio falsely claimed that Kaunda had been removed from office by the army. This was not true, and the 1990 Zambian coup d'état attempt failed.

These widespread protests made Kaunda realize that changes were needed. He promised a referendum on multiparty democracy and lifted the ban on political parties. This quickly led to the formation of eleven new parties. Among these, the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), led by former union leader Frederick Chiluba, was the most important. After pressure from the new parties, the referendum was canceled in favor of direct multi-party elections.

Frederick Chiluba and the MMD

After a new constitution was written, elections were held in 1991. They were generally considered fair. Chiluba won 76% of the presidential vote, and the MMD won 125 out of 150 seats in the National Assembly. UNIP took the remaining 25 seats.

Economically, Chiluba, despite being a former union leader, had more right-leaning policies than Kaunda. With support from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, to whom Zambia owed a lot of money, he opened up the economy. He reduced government involvement, sold state-owned businesses back to private owners (like the important copper mining industry), and removed government support for various goods, especially corn meal.

When one-party rule ended in 1991, many people hoped for a more democratic future for Zambia. However, these hopes were dimmed by how the MMD treated the opposition. Questionable changes to the constitution and the detention of political opponents caused major criticism. Some donor countries, like the United Kingdom and Denmark, stopped providing aid.

Challenges and Political Events

In 1993, the government newspaper, The Times of Zambia, reported a story about a secret UNIP plan to take control of the government in an unconstitutional way. This was called the "Zero Option Plan." The plan included industrial unrest, promoting violence, and organizing large protests. UNIP did not deny the plan existed but said it was not official party policy. The government responded by declaring a state of emergency and detaining 26 people. Seven of these, including Kenneth Kaunda's son Wezi Kaunda, were charged with offenses against the security of the state. The rest were released.

Before the 1996 elections, UNIP formed an alliance with six other opposition parties. Kenneth Kaunda had retired from politics earlier. But after internal problems in the party due to the "Zero Option Plan" scandal, he returned, replacing his own successor. Chiluba's government then changed the constitution. This new rule banned people whose parents were not both Zambian citizens from becoming president. This was directly aimed at Kaunda, whose parents were both from Malawi. In protest, UNIP and its allies boycotted the elections. Chiluba and the MMD then easily won.

In 1997, things became more intense. On 28 October, a coup attempt took place. A group of army commanders took control of the national radio station, announcing that Chiluba was no longer president. Regular forces ended the coup after Chiluba again declared a state of emergency. One person was killed during the operation. After the failed coup, the police arrested at least 84 people accused of involvement. Among them were Kenneth Kaunda and Dean Mungomba, leader of an opposition party. These arrests were criticized as illegal both inside and outside Zambia. Kaunda was released in June the following year. However, 44 of the soldiers who took part in the coup were sentenced to death in 2003.

2001 Elections and Beyond

Before the elections in 2001, Chiluba tried to change the constitution to allow him to run for a third term. He was forced to withdraw this idea after protests from within his own party and from the Zambian public. His chosen successor was Levy Patrick Mwanawasa.

After 2008

From 2011 to 2014, Zambia's president was Michael Sata. He passed away on 28 October 2014, becoming the second Zambian leader to die in office after Levy Mwanawasa in 2008. Rupiah Banda was president of Zambia after Mwanawasa's death from 2008 to 2011. He lost the election to Michael Sata in 2011.

After Sata's death, Vice President Guy Scott, who was of Scottish descent, became acting President of Zambia. On 24 January 2015, it was announced that Edgar Chagwa Lungu had won the election to become the 6th President in a very close race. In August 2016 Zambian general election, President Edgar Lungu won re-election by a small margin in the first round. The opposition claimed there was fraud, but the ruling Patriotic Front (PF) rejected these claims.

In the August 2021 presidential election, opposition leader Hakainde Hichilema defeated the sitting President Edgar Lungu by a large margin. On 24 August 2021, Hakainde Hichilema was sworn in as the new President of Zambia.

See also

- Prime Minister of Zambia

- History of Africa

- History of Southern Africa

- Kazembe

- Kenneth Kaunda

- List of presidents of Zambia

- Monuments and Historic Sites of Zambia

- Politics of Zambia

- Lusaka history and timeline

In Spanish: Historia de Zambia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Zambia para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |