History of the United States Merchant Marine facts for kids

The maritime history of the United States is all about America's connection to the oceans, seas, and big rivers. It looks at how the U.S. has used ships for trade, how these ships were paid for, and who worked on them. Having American-owned ships isn't always necessary for lots of foreign trade. Sometimes, it's cheaper to let other countries carry goods. But, especially during wars, it's really helpful for a country to have its own strong merchant fleet.

The Story of American Ships

Early Days of Shipping

The story of American ships began in 1607, when the first successful English colony was set up in Jamestown, Virginia. For many years, the colony struggled until more settlers arrived in the late 1600s. They started growing tobacco to sell to England.

From the very beginning, building ships was a very important job for the colonists. Before the American Revolutionary War, more people in New England worked in shipbuilding and sailing than in farming. Even with rules from England about building ships, Massachusetts was said to have one ship for every hundred people! Many important figures, like one out of every four signers of the Declaration of Independence, were shipowners or captains.

Ships in the 1700s

Before 1776, when they were still British colonists, American merchant ships were protected by the Royal Navy. Big ports in the Northeast became busy centers for shipping. They exported tobacco, rice, and other goods from the Southern colonies. From other colonies, they sent out horses, wheat, fish, and lumber. By the 1760s, New England was famous for its shipbuilding. They imported all kinds of manufactured items.

Ships During the Revolutionary War

The first war where the United States Merchant Marine played a role was the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). In 1775, the American government gave special permission to private, armed merchant ships called privateers. These ships were like warships, and their job was to attack enemy merchant ships. They disrupted British supplies along the coast and across the Atlantic. This was how the Merchant Marine started its role in wartime, even before the United States Coast Guard (1790) or the United States Navy (1797) existed. During the Revolution, American ships also got help from France because of a treaty in 1778.

After the Revolution (1783–1790)

After the Revolution ended in 1783, America was responsible for its own ships and citizens. Without a strong navy to protect ships in the Mediterranean Sea from Barbary pirates, the new U.S. government decided to pay money to the pirates.

In 1784, Boston sailors traveled to the Pacific Northwest and started the U.S. fur trade.

In 1785, the ruler of Algiers captured two American ships and demanded money for their crews. Thomas Jefferson, who was ambassador to France, argued that paying would only encourage more attacks. But the young American government was too busy with problems at home to show strength overseas. The U.S. paid the ransom and continued to pay up to $1 million a year for safe passage or to get hostages back. By 1800, these payments were 20 percent of the U.S. government's yearly income!

Jefferson kept arguing against the payments, and George Washington and others started to agree. When the American navy was rebuilt in 1794, it became easier for America to say "no." A mostly successful, undeclared war with French privateers in the late 1790s showed that the U.S. Navy could now protect the nation's interests at sea. These problems led to the First Barbary War in 1801.

After the war, Britain made new rules that hurt American trade. They only allowed British-built ships in their colonies and charged high fees for American ships in other British ports. Other countries also made trade difficult for the U.S.

The U.S. government, under the Articles of Confederation, was too weak to fight back. States tried to make their own rules, but these were not uniform, causing chaos. British ships simply went to ports with no fees.

This trade situation hurt American shipping. In 1789, after the United States Constitution was adopted, people asked Congress for help. Congress passed the Tariff of 1789, which made it cheaper for American ships to carry goods than foreign ships. Coastal trade was only for American ships.

In 1789, American ships used for foreign trade totaled 123,893 tons. In the next eight years, this number grew by 384 percent!

The 1790s

In 1790, new laws were made about sailors and leaving ships without permission. In 1796, laws about "Seaman's Protection Certificates" were passed. After the Revolutionary War, the new United States needed money badly, and much of it came from taxes on imported goods. Because of widespread illegal trade, there was a strong need to enforce these tax laws. So, on August 4, 1790, Congress created the Revenue-Marine, which later became the Revenue Cutter Service. Its job was to enforce tax laws and other maritime rules.

In 1799, the Dutch East India Company, once the world's largest company, went bankrupt. This was partly due to the rise of competitive free trade.

The 1800s: A Century of Change

During the wars with France (1793-1815), the British Royal Navy often stopped and searched merchant ships, including American ones. They were looking for British sailors who had left their service. The Royal Navy didn't recognize American citizenship for those born British, so they forced over 6,000 sailors, who claimed to be American, into their service. This was a big reason for the War of 1812.

Commercial whaling was a huge industry in the U.S. during the 1700s and 1800s. It led to a big drop in whale populations. New Bedford, Massachusetts and Nantucket were the main whaling centers. In 1857, New Bedford had 329 whaling ships.

In 1807, Robert Fulton built the North River Steamboat. It started a regular passenger service between New York City and Albany, New York, which was a big success. This showed that steam-powered boats could be very profitable.

Because of growing problems with Great Britain, the U.S. passed the Embargo Act of 1807. Britain and France were at war, and the U.S. was neutral, trading with both. Both sides tried to stop American trade with the other. President Jefferson wanted to use economic pressure instead of war to protect American rights. These acts were meant to punish Britain for taking American sailors from ships. The later Embargo Acts tried to stop Americans from breaking the embargo. These acts were eventually canceled.

The African slave trade became illegal on January 1, 1808.

By 1807, the amount of goods carried by U.S. ships in foreign trade had grown to 848,307 tons.

The War of 1812

The United States declared war on Britain on June 18, 1812. Reasons included anger about the taking of American sailors, British limits on neutral trade, and British support for Native American tribes. After war was declared, Britain offered to remove the trade limits, but it was too late. American leaders saw it as a "second war for independence." Part of the American plan was to use hundreds of privateers to attack British merchant ships, which hurt British trade, especially in the West Indies.

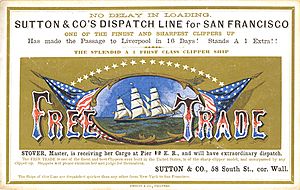

Clipper Ships: Built for Speed

In the U.S., a "clipper" was a type of fast sailing ship, like the Baltimore clipper. These ships were developed before the American Revolution and were used in the War of 1812 for their incredible speed. Clippers were known for being built for speed rather than carrying lots of cargo. While regular merchant ships sailed at under 5 knots (9 km/h), clippers aimed for 9 knots (17 km/h) or more. Sometimes, they could even reach 20 knots (37 km/h)!

Clippers were used for seasonal trades, like tea, where getting the cargo early meant more money, or for passenger routes. These small, fast ships were perfect for valuable goods like spices, tea, people, and mail. The value of their cargo could be huge. The Challenger once returned from Shanghai with "the most valuable cargo of tea and silk ever." There was fierce public competition among clippers, and their travel times were reported in newspapers. These ships didn't last long, usually less than 20 years, before being taken apart. Because they were so fast and easy to steer, clippers often carried cannons and were used by pirates, privateers, and for illegal trade.

After the War of 1812 (1815–1830)

In the 1700s, ships carrying cargo, passengers, and mail between Europe and America would only sail when they were full. But in the early 1800s, as trade with America grew, having a regular schedule became important. Starting in 1818, ships of the Black Ball Line began regular trips between Britain and America. These "packet ships" (named for carrying mail "packets") were famous for sticking to their schedules. This often meant harsh treatment for sailors.

During the 1820s, American whalers started going to the Pacific, leading to more contact with the Hawaiian Islands.

The Erie Canal was built between 1817 and 1825. This encouraged trade within the country and made the port of New York even more important.

In 1826, American ships carried 92.5 percent of foreign trade, a higher percentage than ever before or since. American shipbuilders were known for making fast, strong, and durable ships. Between 1815 and 1840, 540,000 tons of American ships were sold to other countries. Even with higher wages, American ships cost less to run because they needed smaller crews. In 1842, out of 882 whaling ships worldwide, 652 were American.

The 1830s

In 1832, Louis McLane, the Secretary of the Treasury, ordered revenue cutters to make winter trips to help sailors in trouble. Congress made this an official rule in 1837. This was the start of the lifesaving work that the U.S. Coast Guard would become famous for. The SS Great Western was the first steamship built specifically for regular trips across the Atlantic, starting in 1838.

The fast times of these steamships (crossing the Atlantic to New York in 13.5 days) proved that steamers could make the trip faster than the quickest sailing ships. The British government realized that steam power was the future. In 1839, they heavily supported the Cunard Line, which started in 1840 with four wooden steamships. This government support helped Britain's shipping companies get a head start with new types of ships and keep their lead on the ocean.

The 1840s

The first regular steamship service from the west to the east coast of the U.S. began on February 28, 1849, when the SS California (1848) arrived in San Francisco Bay. The California had left New York Harbor on October 6, 1848, sailed around Cape Horn at the tip of South America, and arrived in San Francisco after a journey of 4 months and 21 days. The SS Great Eastern was built between 1854 and 1857 to connect Great Britain with India without needing to stop for coal. It had a difficult history and was never used for its original purpose.

The years before the Civil War saw very fast shipbuilding. The amount of ships used for foreign trade grew from 538,136 tons in 1831 to 2,496,894 tons in 1862. This was the highest amount of shipbuilding until World War I. From 1848 to 1858, an average of 400,000 tons of ships were built each year. This boom was caused by two things: the development of the clipper ship after 1845 and a greater need for shipping.

Clippers were designed for speed, with sharp designs and lots of sails. They were the peak of sailing ship design, especially for long trips to California and the Far East. With good wind, a clipper could outrun a steamship. It was common for clippers to sail over 300 miles a day. The Flying Cloud (clipper) once sailed 374 miles in a single day on a 90-day trip to San Francisco.

The increased demand for shipping came from several factors. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 was a major reason. Wars between Great Britain and China (1840-42 and 1856-60) also shifted some of the China trade to American ships. Problems in Europe in 1848 helped Americans, and the Crimean War, which used many European ships for troops, created new opportunities for American ships. Plus, the natural growth in population, wealth, and production meant more shipping was needed.

The amount of mail between the U.S. and Europe grew a lot, and sailing ships couldn't always deliver it quickly. So, the government started helping ocean shipping by paying for overseas mail service. On March 3, 1845, Congress allowed the Postmaster General to ask for bids on contracts to carry mail abroad. This led to regular subsidized service between New York and cities like Bremen, Havre, Liverpool, and Panama.

This also led to the creation of the U.S. Mail Steamship Company and the Pacific Mail Steamship Company.

The 1850s

As important as the switch from sailing ships to steamships was the slow change from wooden ships to iron and later steel ships. With lots of coal and iron near the sea, skilled workers, and cheap labor, Great Britain quickly took the lead. By 1853, one-fourth of the ships built in Great Britain were steamships, and more than one-fourth were made of iron. In the same year, 22 percent of American ships were steamships, but hardly any iron ships were built in the U.S. American shipbuilders, too confident in their amazing clipper ships, didn't see that the future of sea travel was with nations that could build the cheapest and best iron steamships.

There was a problem with this busy shipbuilding period. The demand from Europe because of the Crimean War was unusually high. Between 1854 and 1859, European nations bought 50,000 tons of ships, compared to 10,000 tons in normal years. Unfortunately, this increase in building sailing ships happened when their time was ending. Between 1850 and 1860, the share of ocean freight carried by steamers grew from 14 to 28 percent. When the unusual demand for sailing ships dropped, as it did in 1858, shipyards built for wooden ships and workers trained for them became idle. Foreign shipyards, already building iron steamships, were in a much better position. The financial crisis of 1857 caused a crash. In 1858, shipbuilding dropped from an average of 400,000 tons a year to 244,000, and in 1859 to 156,000. At the same time, the amount of imports and exports carried by American ships was steadily falling, from 92.5 percent in 1826 to only 65.2 percent in 1861.

Another reason for the decline of American shipbuilding was a big economic change in the U.S. Money was finding new and more profitable places to be invested. Manufacturing, which grew fast after the War of 1812, took some of it. A lot of money also went into building canals and railways. Between 1820 and 1838, states borrowed over $110,000,000 for roads, canals, and railroads. From 1830 to 1860, over 30,000 miles of railroad were built, mostly with private money. Adventurous people turned from the sea to the undeveloped West, and money shifted from shipbuilding to developing natural resources.

In 1852, the lighthouse board started publishing the first Light List and Notice to Mariners, which are guides for sailors. In 1854, Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry opened trade relations with Japan by signing the Convention of Kanagawa. The discovery of petroleum in Titusville, Pennsylvania, on August 27, 1859, marked the beginning of the end for commercial whaling in the U.S. Kerosene, made from crude oil, replaced whale oil in lamps. Later, electricity replaced oil lamps, and by the 1920s, there was no demand for whale oil.

The use of clippers began to decline after the economic downturn of 1857 and continued with the slow introduction of the steamship. Even though clippers could be much faster than early steamships, clippers depended on the wind, while steamers could reliably keep to a schedule. "Steam clippers" were developed around this time, with extra steam engines for when there was no wind.

In 1859, the "Memphis and St. Louis Packet Line," which later became the Anchor Line, was formed. It mainly served these two cities and places in between. The Anchor Line was a steamboat company that operated ships on the Mississippi River between St. Louis, Missouri and New Orleans, Louisiana, from 1859 to 1898.

The 1860s

The final blow to clipper ships came with the Suez Canal, which opened in 1869. It provided a huge shortcut for steamships between Europe and Asia, but it was hard for sailing ships to use.

The Civil War and Shipping

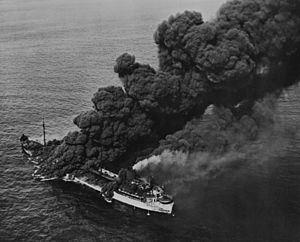

Merchant shipping was a big target during the U.S. Civil War. For example, the CSS Alabama, a Confederate warship, spent months capturing and burning ships in the North Atlantic. Other Confederate ships also attacked merchant vessels.

The reasons for the decline of the merchant marine were already happening before the Civil War. The war just made it worse, and the merchant marine didn't recover until it was artificially boosted during World War I. In 1861, American ships in foreign trade totaled 2,496,894 tons, but by 1865, it dropped to 1,518,350 tons. The percentage of imports and exports carried by American ships fell from 66.2 to 27.7 in the same years. This decrease of about 900,000 tons was mainly due to two things: losses from Confederate ships like the Alabama, and the sale of 751,595 tons of ships abroad between 1862 and 1865. This happened because people lost confidence, profits dropped due to captures and high insurance, and cotton shipments abroad stopped.

A second round of ocean-mail contracts was approved by Congress on May 28, 1864. The U.S. and Brazil made a 10-year contract for monthly trips between the U.S. and South America.

From 1866 to 1870, the first attempt to form a union for merchant seamen on the West Coast, the "Seamen's Friendly Union and Protective Society," quickly failed.

The Civil War severely damaged the merchant marine. Losses from Confederate ships and many sales abroad reduced the number of ships. Not switching to iron steamships fast enough gave British builders an advantage. But most importantly, more profitable investments in transportation and natural resources after the war drew money away from the sea. A lack of government interest also contributed to the decline of American shipping.

The five years after the Civil War showed a small recovery, but the decline continued. American shipping in foreign trade and fishing, which was 2,642,628 tons in 1870, dropped to 826,694 tons in 1900. In 1860, American ships carried 66.5 percent of imports and exports, but this dropped to 35.6 percent in 1870, 13 percent in 1880, 9.4 percent in 1890, and 7.1 percent in 1900.

The 1870s

By 1870, new inventions like the screw propeller and the triple expansion engine made shipping across oceans profitable. This started an era of cheap and safe travel and trade worldwide. Starting in 1873, ship officers had to pass required license exams. In 1874, the New York Nautical School was founded to train young men for careers at sea. It was the first school of its kind in the U.S. and later became the State University of New York Maritime College. Also in 1874, the union that would become the Marine Engineers' Beneficial Association was formed. By 1876, Plimsoll marks (lines on a ship's hull showing how much it can be loaded) were required on all U.S. vessels.

The 1880s

In 1880, the passenger steamship Columbia was the first ship to use Thomas Edison's incandescent light bulb and a dynamo (a type of electrical generator). The Sailors' Union of the Pacific (SUP) was founded on March 6, 1885, in San Francisco. It's a labor union for sailors, fishermen, and boatmen on U.S. ships. Andrew Furuseth, a key figure, was elected union secretary in 1891. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) was founded in 1886 by Samuel Gompers as a national group of skilled workers' unions. Several maritime unions joined the AFL. In 1887, the Merchant Marine and Fisheries Committee was formed in Congress.

The 1890s

In 1891, the Massachusetts Maritime Academy opened. On July 29, 1891, Andrew Furuseth combined two unions to form the new Sailors' Union of the Pacific. He was secretary of the SUP until 1935. In 1892, the International Seamen's Union (ISU) was formed in Chicago as a group of independent unions. In 1893, the ISU joined the American Federation of Labor. In 1895, the Maguire Act of 1895 was passed, meaning sailors could no longer be jailed for leaving coastal vessels. In 1897, the White Act of 1898 was passed, which stopped jailing U.S. citizens for leaving ships in American waters and ended physical punishment.

The Ocean Mail Act of 1891 provided payments to different types of steamships for carrying mail. This started a trade-route system that is still largely the same today. The Act stayed in effect until 1923, and total payments were $29,630,000.

The Early 1900s

In 1905, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or "the Wobblies") was founded, mainly representing unskilled workers. They were important in American labor for about 15 years. In 1908, Andrew Furuseth became president of the International Seamen's Union and served until 1938.

The 1910s

During this time, Andrew Furuseth successfully pushed for new laws that became the Seamen's Act. During World War I, there was a shipping boom, and the ISU's membership grew to over 115,000. But when the boom ended, membership shrank to 50,000.

. In 1915, the Seamen's Act of 1915 became law. This act greatly changed the life of American sailors. Among other things, it:

- Stopped jailing sailors who left their ship.

- Reduced punishments for not obeying orders.

- Set working hours for sailors at sea and in port.

- Required a minimum quality for ship's food.

- Regulated how sailors' wages were paid.

- Required specific safety levels, especially enough lifeboats.

- Required a certain percentage of sailors on a ship to be qualified Able Seamen.

- Required at least 75 percent of sailors on a ship to understand the language spoken by the officers.

Laws like the Seaman's Act put U.S.-flagged ships at a disadvantage compared to countries without such rules. Ship owners could avoid these protections by moving their ships to the Panamanian "flag of convenience" (registering their ships in Panama). The Belen Quezada, the first foreign ship registered in Panama, was used to carry forbidden alcohol between Canada and the U.S. during Prohibition. Besides avoiding the Seamen's Act, Panamanian-flagged ships in this early period paid sailors much lower wages, similar to Japanese pay scales.

President Woodrow Wilson signed the act to create the United States Coast Guard on January 28, 1915. This act combined the Revenue Cutter Service with the Lifesaving Service. The Coast Guard later took over the United States Lighthouse Service in 1939 and the Navigation and Steamboat Inspection Service in 1942.

World War I and Shipping

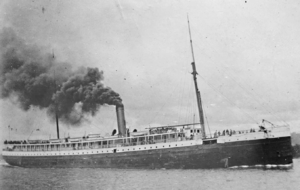

Shipbuilding became a huge industry during World War I, focusing on merchant ships and tankers. Merchant ships were often sunk until the convoy system was used. Convoys were groups of merchant ships traveling together with British and Canadian naval escorts. Convoys were slow but very good at stopping U-boat attacks. Troops were sent on fast passenger liners that could easily outrun submarines.

In World War I, Britain, as an island nation, relied heavily on foreign trade and imported goods. Germany found that their submarines, or U-boats, were very effective against merchant ships. They could easily patrol the Atlantic even when Allied ships controlled the surface.

By 1915, Germany was trying to blockade Britain by sinking cargo ships, including many passenger vessels. Submarines, which relied on stealth and couldn't withstand a direct attack, found it hard to give warning before attacking or to rescue survivors. This meant many civilians died. This was a major reason why neutral countries, like the United States, turned against Germany. It also led to the U.S. eventually entering the war. Historian Dr. Rodney Carlisle says that the sinking of nine U.S. merchant ships finally made President Wilson ask Congress to declare war.

Over time, using defended convoys of merchant ships allowed the Allies to keep shipping across the Atlantic, despite heavy losses. The Royal Navy had used convoys in the Napoleonic Wars, and they had protected troopships in this war. But the idea of using them for merchant shipping was debated. Some worried that putting merchant ships into convoys would just give German U-boats more targets. It was also a huge logistical challenge.

With the ability to replace lost ships, the decision to use convoys became easier. After successful tests in early 1917, the first formal convoys were organized in late May. By autumn, the convoy system was well-organized, and losses for ships in convoy dropped sharply. Ships in convoy had 2% losses, compared to 10% for ships traveling alone. The convoy loss rate dropped to 1% in October. However, convoys were not mandatory, and monthly loss rates didn't fall below 1916 levels until August 1918.

The need to manage the merchant marine during wartime was clear in World War I. Submarine attacks and merchant raiders severely hurt the Allied merchant fleet. When Germany started sinking ships without warning again in 1917, U-boats sank ships faster than new ones could be built.

Between the Wars (1919–1941)

One of the ISU's successes was the strike of 1919, which led to the highest wages ever for deep-sea sailors in peacetime. However, the ISU also had failures. After failed contract talks, the ISU called an all-ports strike on May 1, 1921. The strike lasted only two months and failed, leading to 25 percent wage cuts. The ISU, like other AFL unions, was criticized for being too conservative. In 1929, the California Maritime Academy was established.

In 1933, John L. Lewis founded the Committee for Industrial Organizations within the AFL. This group split from the AFL in 1938 and became the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). In 1934, Harry Lundeberg joined the Sailor's Union of the Pacific. The ISU was weakened when the Sailors' Union of the Pacific left in 1934. The ISU claimed the SUP was being influenced by "radicals" and demanded they stop working with the Maritime Federation. The SUP refused, and the ISU removed their charter. The ISU was involved in the 1934 West Coast waterfront strike, which lasted 83 days and led to all West Coast ports becoming unionized.

West Coast sailors left their ships to support the International Longshoremen's Association workers, leaving over 50 ships idle in San Francisco harbor. ISU officials reluctantly supported this strike. In clashes with police between July 3 and July 5, 1934, three protesters were killed and many were injured. During talks to end the strike, sailors received better conditions, including a three-watch system (meaning more rest), pay raises, and better living conditions. In April 1935, an umbrella union called the Maritime Federation was formed in Seattle to represent ISU members, officers, and longshoremen. Harry Lundeberg was its first president.

The U.S. merchant marine was in decline in the mid-1930s. Few ships were being built, existing ships were old, unions were fighting, ship owners disagreed with unions, and crews' morale was low. Congress acted to fix these problems in 1936. The Merchant Marine Act of 1936 created the United States Maritime Commission to develop and maintain a strong American merchant marine, promote U.S. trade, and help with national defense.

The commission realized that trained merchant marine workers were vital. They asked the United States Coast Guard to help create a training program for merchant marine personnel. This new program, called the United States Maritime Service, started in 1938. It used both civilian and Coast Guard instructors to improve the training of merchant mariners.

Joseph P. Kennedy was named head of the Maritime Commission in 1937. On October 15, 1938, the Seafarers International Union of North America was formed.

New Unions Form

In 1936, a sailor named Joseph Curran gained attention. From March 1 to March 4, Curran led a strike on the SS California in San Pedro, California. Sailors along the East Coast went on strike to protest how the California's crew was treated. Curran became a leader of the 10-week strike, forming a group called the Seamen's Defense Committee. In October 1936, Curran called another strike, partly to improve working conditions and partly to challenge the ISU. This four-month strike stopped 50,000 sailors and 300 ships along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

Believing it was time to leave the conservative ISU, Curran started recruiting members for a new union. So many people joined that hundreds of ships were delayed as sailors signed union cards.

In May 1937, Curran and other leaders formed the National Maritime Union. At its first meeting in July, about 30,000 sailors switched from the ISU to the NMU, and Curran was elected president. Within a year, the NMU had over 50,000 members, and most American shipping companies had contracts with them.

In August 1937, William Green, president of the American Federation of Labor, took control of the ISU to rebuild it. Harry Lundeberg, who also led the Sailor's Union of the Pacific, was given the Seafarer's International Union charter by Green on October 15, 1938. The new union represented 7,000 members on the East and Gulf coasts. Today, the SIU holds the charters for both the NMU and SUP.

The 1940s

World War II and Merchant Mariners

When the U.S. entered World War II, the merchant marine and Coast Guard had to grow immediately. The Maritime Commission created the War Shipping Administration in February 1942. This new agency took on important war functions, including maritime training. However, a few weeks later, the Maritime Service was moved back to the Coast Guard. This allowed the War Shipping Administration to focus on organizing American merchant shipping, building new ships, and delivering cargo where it was most needed.

The U.S. planned to deal with the crisis by building many mass-produced cargo ships and transports. When World War II began, the Maritime Commission started a fast shipbuilding program. Experienced shipyards built complex vessels like warships. New shipyards, which opened very quickly, generally built simpler ships like the "Liberty ships." By 1945, shipyards had completed over 2,700 "Liberty" ships and hundreds of "Victory ships," tankers, and transports.

All these new ships needed trained officers and crews. The Coast Guard provided much of the advanced training for merchant marine personnel. Merchant sailors trained at two large stations: Fort Trumbull in New London, Connecticut, on the East Coast, and Government Island in Alameda, California, on the West Coast. In 1940, Hoffman Island in New York Harbor became the third training station. During the war, more stations were added in Boston, Port Hueneme, California, and St. Petersburg, Florida.

Training ships included the steamships American Seaman, American Mariner, and American Sailor. The American Seaman, a 7,000-ton ship, carried 250 trainees plus its regular crew. It had machine shops, lifeboats, and modern navigation equipment for training. The Coast Guard also crewed the sailing ships Tusitala and Joseph Conrad. These training ships were important commands.

Experienced merchant marine personnel trained for three months, while new personnel trained for six months. Pay was based on their highest certified position. New students received cadet wages. American citizens at least 19 years old with one year of service on American merchant ships were eligible. Coast Guard training of merchant mariners was crucial to winning the war. Thousands of sailors who crewed the new American merchant fleet were trained by the Coast Guard.

The Coast Guard only managed the Maritime Service for ten months after the U.S. entered the war. Merchant marine training and most other activities were transferred to the new War Shipping Administration on September 1, 1942. This allowed the Coast Guard to focus more on its war role and put merchant marine management under one agency. However, as the Coast Guard's training role ended, it took on the job of licensing seamen and inspecting merchant vessels.

The Atlantic Ocean was a major battle zone during World War II (Battle of the Atlantic). When Germany declared war on the U.S., the East Coast of the United States became an easy target for German U-boats. After a very successful attack by five long-range U-boats, the offensive grew with short-range U-boats that could refuel from supply U-boats. From February to May 1942, 348 ships were sunk, with only 2 U-boats lost in April and May. U.S. naval commanders were slow to use the convoy system that had protected trans-Atlantic shipping. Without coastal blackouts, ships were easy targets against the bright lights of American towns.

Several ships were torpedoed within sight of East Coast cities like New York City and Boston. Some civilians even sat on beaches and watched battles between U.S. and German ships.

Once convoys and air cover were introduced, the number of sinkings dropped. The U-boats then moved to attack shipping in the Gulf of Mexico, causing 121 losses in June. For example, the tanker Virginia was torpedoed at the mouth of the Mississippi River by the German submarine U-507 on May 12, 1942, killing 26 crewmen. Again, when defenses were put in place, ship sinkings decreased, and U-boat sinkings increased.

The overall effect of this campaign was severe: a quarter of all wartime sinkings—3.1 million tons. There were several reasons for this. Admiral Ernest King, the naval commander, was against British recommendations to use convoys. U.S. Coast Guard and Navy patrols were predictable, allowing U-boats to avoid them. There was poor cooperation between military branches, and the U.S. Navy didn't have enough suitable escort ships.

In 2017, Sadie O. Horton, who worked on a U.S. Merchant Marine barge during World War II, was officially recognized as a veteran after her death. She was the first recorded female Merchant Marine veteran of World War II.

Challenges During Wartime

During World War II, merchant sailors worked and took orders from naval officers. Some wore uniforms and were trained to use guns, but they were officially considered volunteers, not military members. Some newspaper columnists unfairly called merchant seamen "draft dodgers," "criminals," and "Communists."

This came to a head when a columnist claimed that merchant seamen refused to work on Sundays due to union rules, forcing sick USMC servicemen to unload their own supplies off Guadalcanal. He also said these seamen received "fabulous pay" while Navy men got "modest pay." The National Maritime Union and seven other unions sued the newspaper publisher for spreading what they said was an untrue story. They pointed out that government benefits like family allotments, low-cost insurance, and health care balanced the pay of civilian seamen. They also showed a report from Admiral William Halsey, Jr., who praised the "co-operation, efficiency and courage" of merchant seamen and stated that "In no instance have merchant marine seamen refused to discharge cargo from their vessels." They won their lawsuit, but the negative image lasted for decades.

The Seafarers International Union of North America says that what was ignored was that seamen were only paid by the ship owner when their ships were active. A seaman whose ship was torpedoed was off the payroll the moment he was injured or landed in a lifeboat. Surviving seamen had to find their own way back to the U.S. from places like Murmansk, Russia, to get another ship. Until then, they weren't paid. Also, they would be drafted into the military if they didn't find another ship within 30 days. Their wartime losses were among the highest of any group on the front lines. They died at a rate of 1 in 24. In total, 733 American cargo ships were lost, and 8,651 of the 215,000 who served died.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was a big supporter of merchant sailors. In 1936, he urged Congress to pass the Merchant Marine Act of 1936. This act set up a 10-year program to build ships for peacetime trade that could be used by the Navy during war. It also created a training program for seamen that linked them to the military in wartime. This law helped the country fight the Axis powers a few years later, but not before heavy losses on the East Coast from German submarines by the end of 1941. That year, Germans sank 1,232 Allied and neutral ships worldwide, including those crewed by the Merchant Marine. The next year was even worse, with 1,323 Allied ships lost, while Germany lost only 87 submarines. More than 1,000 merchant seamen died within sight of the East Coast, and it was common for people on the shore to find their bodies washed up on the sand.

Roosevelt said during the war, "Mariners have written one of its most brilliant chapters. They have delivered the goods when and where needed... in the biggest, the most difficult and dangerous job ever undertaken."

But after Roosevelt's death in 1945, the Merchant Marine lost its strongest supporter. The United States Department of War, the same government branch that recruited them, opposed the Seaman's Bill of Rights in 1947. This stopped the law in Congress, effectively ending any chance for seamen to get the thanks of the nation. For 43 years, the U.S. government denied them benefits until Congress gave them veterans' status in 1988. This was too late for 125,000 mariners, about half of those who had served.

Today, there are memorials to honor these heroes, like The American Merchant Marine Veterans Memorial in San Pedro, California, and the American Merchant Mariners' Memorial in Lower Manhattan. The old Navy – Merchant Marine Memorial in Washington, D.C. honors those who died during World War I.

Since World War I and World War II, many Merchant Marine officers have also served in the United States Naval Reserve. Graduates of the United States Merchant Marine Academy are usually commissioned into the USNR. A special badge, the Naval Reserve Merchant Marine Badge, has existed since the early 1940s to recognize Merchant Marine personnel who serve in the Navy. World War II USMM members were eligible for several medals, including the Merchant Marine Distinguished Service Medal and the Merchant Marine World War II Victory Medal.

In the late 1940s, the Liberian open registry was created by Edward Stettinius Jr., who was Franklin D. Roosevelt's Secretary of State during World War II. This allowed ships to register in Liberia, which became popular as Panama's registry became less attractive.

On March 11, 1949, Greek shipping owner Stavros Niarchos registered the first ship under the Liberian flag, the World Peace. When Stettinius died in 1950, ownership of the registry went to the International Bank of Washington. Within 18 years, Liberia became the world's largest ship registry, surpassing the United Kingdom.

The 1950s

The United States Maritime Commission was ended on May 24, 1950. Its jobs were split between the U.S. Federal Maritime Board, which regulated shipping and gave out money for building and operating ships, and the Maritime Administration, which managed these programs and maintained the national defense reserve merchant fleet. The American Maritime Officers (AMO) union was formed on May 12, 1949, by Paul Hall as part of the Seafarers International Union of North America. Its first members were all civilian seafaring veterans of World War II.

The Korean War and Shipping

On March 13, 1951, the United States Secretary of Commerce created the National Shipping Authority (NSA). Its job was to provide ships from the United States Maritime Administration's (MARAD) National Defense Reserve Fleet (NDRF). These ships would meet the needs of the military and other government agencies when private U.S. merchant ships weren't enough. During wars, the NSA also took over privately owned merchant ships for military use. Immediately after it was created, the NSA reactivated ships to help America's European allies transport coal and other materials to rebuild their defenses.

During the Korean War, there were few major shipping problems, other than needing to get forces ready again after World War II. About 700 ships from the NDRF were activated for service to the Far East. Also, a worldwide shortage of shipping space between 1951 and 1953 required over 600 ships to be reactivated to carry coal to Northern Europe and grain to India. The commercial merchant marine was the main support for shipping across the Pacific. From just six ships at the start of the war, this number grew to 255. According to the Military Sealift Command (MSTS), commercial vessels carried 85 percent of the dry cargo needed during the Korean War. Over $475 million, or 75 percent of the MSTS budget in 1952, was paid directly to commercial shipping companies.

In addition to ships directly assigned to MSTS, 130 laid-up Victory ships in the NDRF were brought out by the Maritime Administration and rented to private shipping firms for use by MSTS.

MSTS ships not only delivered supplies but also acted as naval support. When the United States Army's X Corps landed at Inchon in September 1950, 13 USNS cargo ships, 26 rented American ships, and 34 Japanese-crewed merchant ships, all controlled by MSTS, took part in the invasion. Shipping needs were met quickly during the Korean War. American troops initially lacked important equipment, but military and commercial vessels quickly delivered the tools needed to fight back. According to the MSTS, 7 tons of supplies were needed for every Marine or soldier going to Korea, and an additional ton for each month they stayed. Cargo ships unloaded supplies day and night, making Busan a very busy port. The success of the U.S. Merchant Marine during this crisis showed how important maritime readiness was. Besides delivering equipment to American forces, more than 90 percent of all American and other United Nations' troops, supplies, and equipment were delivered to Korea through the MSTS with the help of commercial cargo vessels. A bridge of ships, much like in World War II, crossed the Pacific Ocean during the three years of fighting.

Merchant ships played an important role in evacuating United Nations troops from Hungnam, after the Battle of Chosin Reservoir. The Merchant Marine and Navy evacuated over 100,000 U.N. troops and another 91,000 Korean refugees. They also moved 350,000 tons of cargo and 17,500 vehicles in less than two weeks. One famous rescue was by the U.S. merchant ship SS Meredith Victory. Just hours before advancing communists drove U.N. forces from North Korea in December 1950, the ship, built for 12 passengers, carried over 14,000 Korean civilians from Hungnam to Busan in the south. First mate D. S. Savastio, with only first aid training, delivered five babies during the three-day trip. Ten years later, the Maritime Administration honored the crew with a Gallant Ship Award.

Privately owned American merchant ships helped deploy thousands of U.S. troops and their equipment. Admiral C. Turner Joy, commander of U.S. Naval Forces in the Far East, praised the Merchant Marine. He said, "The Merchant Mariners in your command performed silently, but their accomplishments speak loudly. Such teammates are comforting to work with."

Government-owned merchant vessels from the National Defense Reserve Fleet (NDRF) have supported emergency shipping needs in seven wars and crises. During the Korean War, 540 vessels were activated. From 1955 to 1964, another 600 ships were used to store grain for the United States Department of Agriculture. Another shipping shortage after the Suez Canal closing in 1956 caused 223 cargo ships and 29 tankers to be activated from the NDRF.

Later 1950s

In 1953, the Brotherhood of Marine Engineers (BME) gained independence within the SIUNA. They adopted their first constitution and elected officers. The constitution was designed for fair elections and transparency. Wilbur Dickey was elected the first president on December 15, 1953. In September 1954, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) recognized the new union, giving it control over "licensed engine room personnel on self-propelled vessels."

The BME Welfare Plan grew quickly. In August 1954, it had over $100,000 in assets. The plan offered benefits like full surgery coverage for members and their families. In February 1955, the union started working on the "first pension plan ever for U.S. merchant marine officers."

In 1955, Joseph Curran became a vice-president of the AFL-CIO. The AFL and CIO merged in 1955 under John L. Lewis. In 1957, Wilbur Dickey resigned, and Raymond McKay became president on January 17, 1957. Later that year, McKay and the president of the Marine Engineers' Beneficial Association (MEBA) signed an agreement for BME to merge with several MEBA local unions. The new group was called MEBA's Great Lakes District Local 101. On January 28, 1957, Harry Lundeberg died. Shortly after, Paul Hall became president of the Seafarers International Union of North America. That year, Raymond McKay became president of American Maritime Officers, which left SIU and joined MEBA. Also that year, Michael Sacco joined the Seafarers International Union of North America.

The Late 1900s

The 1960s

In 1960, after a change in MEBA, American Maritime Officers became "District 2 MEBA." In 1961, the Federal Maritime Commission took over the regulatory jobs of the Federal Maritime Board. During the Berlin crisis of 1961, 18 National Defense Reserve Fleet vessels were activated and stayed in service until 1970. The Vietnam War required 172 NDRF vessels to be activated.

The Vietnam War and Shipping

During the Vietnam War, ships crewed by civilian seamen carried 95 percent of the supplies used by the U.S. Armed Forces. Many of these ships sailed into combat zones under fire. The Mayagüez incident involved the capture of sailors from the American merchant ship SS Mayaguez. The crisis began on May 12, 1975, when Khmer Rouge naval forces captured the SS Mayaguez in international waters claimed by Cambodia. They removed its crew for questioning. Surveillance showed the ship was moved to Koh Tang, an island about 50 km off Cambodia's coast. Sadly, the ship's crew had been released unharmed, unknown to the U.S. Marines or the U.S. command, before the Marines attacked. This incident was the last official battle of the United States' involvement in the Vietnam War.

The 1970s

In 1970, the Merchant Marine Act approved a program to build subsidized ships. On March 5, 1973, Joseph Curran resigned as president of NMU, and Shannon J. Wall took over. In 1976, the first woman was admitted to the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy. Since 1977, the Ready Reserve Fleet has handled most of the work previously done by the National Defense Reserve Fleet. The RRF played a major role in Operation Desert Shield/Operation Desert Storm from August 1990 to June 1992. During this time, 79 vessels were activated, carrying 25% of the military equipment and 45% of the ammunition needed.

The 1980s

In 1981, the Maritime Administration came under the control of the United States Department of Transportation. In 1988, Frank Drozak died, and Michael Sacco replaced him as president of the Seafarers International Union of North America.

The 1990s

In 1992, "District 2" went back to its original name, "American Maritime Officers," while still being an independent union within MEBA. In 1993, Raymond T. McKay died, and his son Michael McKay became president of American Maritime Officers. AMO finally left MEBA in 1994 and lost its AFL-CIO connection. This was restored about 10 years later, on March 12, 2004, when Michael Sacco gave AMO a charter from the Seafarers International Union of North America.

Two RRF tankers, two RO/RO (roll-on/roll-off) ships, and a troop transport ship were needed in Somalia for Operation Restore Hope in 1993 and 1994. During the Haitian crisis in 1994, 15 ships were activated for Operation Uphold Democracy. In 1995 and 1996, four RO/RO ships delivered military cargo for U.S. and U.K. support to NATO peacekeeping missions. Four RRF ships were activated to provide help for Central America after Hurricane Mitch in 1998. Three RRF ships currently support the Afloat Prepositioning Force with two specialized tankers and one dry cargo vessel.

The 2000s and Beyond

On October 22, 2001, the Merchant Marine Act of 2001 was passed, planning for the construction of 300 ships over ten years. In 2003, 40 RRF ships were used to support Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. This RRF help was significant, moving equipment and supplies into combat areas. By early May 2005, RRF support included 85 ship activations, moving almost 25% of the equipment needed to support the U.S. Armed Forces in Iraq. The Military Sealift Command (MSC) is also involved in the current Iraq War, having delivered 61 million square feet of cargo and 1.1 billion gallons of fuel by the end of the first year alone. Merchant mariners are being recognized for their contributions in Iraq. For example, in late 2003, Vice Adm. David Brewer III, commander of Military Sealift Command, awarded the officers and crewmembers of MV Capt. Steven L. Bennett the Merchant Marine Expeditionary Medal.

On January 8, 2007, Tom Bethel was appointed by the AMO national executive committee to finish the term of former president Michael McKay. The RRF was called upon to provide help to Gulf Coast areas after Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita in August and September 2005. The Federal Emergency Management Agency asked for eight vessels to support relief efforts. These ships provided housing and food for refinery workers, oil spill response teams, and longshoremen. One vessel even provided electrical power.

In 2020, Congress passed the Merchant Mariners of World War II Congressional Gold Medal Act to recognize the merchant mariners for their bravery and contributions during the war. During World War II, nearly 250,000 civilian merchant mariners served with the U.S. military, delivering supplies and personnel to countries involved in the war. Between 1939 and 1945, 9,521 merchant mariners lost their lives—a higher percentage than in any military branch, according to the National WWII Museum.

"President Franklin D. Roosevelt called their mission the most difficult and dangerous transportation job ever undertaken," House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said at the ceremony, which was held at the U.S. Capitol.

The Congressional Gold Medal will be displayed at the American Merchant Marine Museum in Kings Point, New York. Also, each of the surviving merchant mariners—now estimated to be about 12,000 from World War II—will receive a bronze copy of the award.

Two of the World War II mariners, Charles Mills, 101, and Dave Yoho, 94, attended the ceremony at the U.S. Capitol.

Images for kids

-

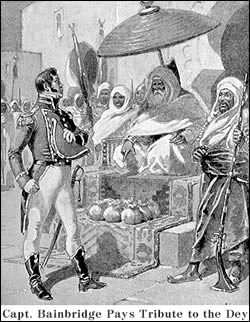

Captain William Bainbridge paying tribute to the Dey

-

The SS Great Eastern

-

Andrew Furuseth (left) with Senator La Follette (center), and writer Lincoln Steffens, c. 1915

-

Able Seamen were in high demand during World War II.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |