History of the iron and steel industry in the United States facts for kids

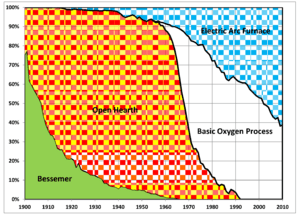

The iron and steel industry in the United States has changed a lot over time. It has followed similar paths to other countries in how it uses new technology. In the 1800s, the US stopped using charcoal to melt iron ore and started using coal. It also began using the Bessemer process and built very large steel factories.

Later, in the 1900s, the US industry started using the open hearth furnace and then the basic oxygen steelmaking process. The American iron and steel industry was at its biggest in the 1940s and 1950s. Since then, it has changed to smaller factories called "mini-mills" and special mills. These newer mills often use old iron and steel scrap instead of new iron ore.

Contents

Early American Iron Making

Before the 1800s, making iron needed a lot of charcoal. Britain, which used to have huge forests, couldn't grow enough trees to make all the charcoal it needed for iron. By 1700, Britain had to buy a lot of iron from Sweden.

Britain then looked to its American colonies, which had endless forests, to get iron. In 1718, British investors opened an iron furnace near Perryville, Maryland. It started sending iron back to Britain. This success led to more companies building many iron furnaces around Chesapeake Bay. These furnaces used bog iron ore, which was easy to find.

By 1751, Virginia and Maryland were sending 2,950 tons of raw iron (called pig iron) to Britain each year. At that time, Britain made about 20,000 tons of iron a year.

While some furnaces were built to send iron to Britain, many others were made in the 1700s to supply the American colonies themselves. These iron furnaces were usually built near rivers for water power. They also needed forests for charcoal, iron ore, and limestone (used to help melt the iron). Plus, the furnace had to be close to a big town or a way to transport goods by water.

British businesses had different ideas about colonial iron. Manufacturers liked the lower prices of iron from the colonies. But the British iron and steel industry didn't like the competition. The British Parliament made a deal in the Iron Act of 1750. This law removed the tax on pig iron from the colonies. However, it stopped the colonies from making steel or iron plates. The colonial governments mostly ignored this law.

By 1776, there were about 80 iron furnaces across the American colonies. They were making almost as much iron as Britain. One guess is that they made 30,000 tons of iron each year. If that's true, the new United States was the third-largest iron producer in the world, after Sweden and Russia.

Important Iron Furnaces Before the 1800s

| Name | Location | Started | Ended |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boonton Iron Works | Boonton, New Jersey | around 1770 | 1911 |

| Catoctin Furnace | Catoctin Furnace, Maryland | 1774 | 1903 |

| Falling Creek Ironworks | Chesterfield County, Virginia | 1622 | 1622 |

| Furnace Mountain | Loudoun County, Virginia | around 1790 | around 1870 |

| Hunter's Ironworks | Falmouth, Virginia | around 1750 | 1782 |

| Huntingdon Furnace | Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania | 1796 | around 1880 |

| Neabsco Iron Works | Woodbridge, Virginia | around 1737 | |

| New Roxbury Ironworks Site | Woodstock, Connecticut | 1757 | |

| Patuxent Iron Works | Anne Arundel County, Maryland | 1705 | 1856 |

| Principio Furnace | Cecil County, Maryland | 1719 | 1925 |

| Stirling Iron Works | Monroe, New York | 1761 | 1842 |

| Taunton Iron Works | Raynham, Massachusetts | 1656 | 1876 |

| Washington Iron Furnace | Rocky Mount, Virginia | around 1770 |

Iron Making in the Early 1800s

In the early 1800s, wood for charcoal was easy to find in the eastern states. So, iron smelters (factories that melt iron) were built close to where iron ore was found. The "bog iron" ores used earlier were spread out but were also small and ran out quickly.

In the late 1700s, iron furnaces moved away from the bog iron of the swamps near the coast. They went to bigger iron ore deposits further inland. Being inland also meant the furnaces were closer to limestone, which was used to help melt the iron. Being near larger ore deposits made it possible to build bigger, more lasting iron smelters.

Before 1850, most US iron smelting happened near iron deposits in eastern Pennsylvania, New York, and northern New Jersey. New Jersey's main iron ore area, near Dover, had iron smelters starting in 1710. The Cornwall Iron Furnace in Pennsylvania was built right next to an iron deposit. The Adirondack iron ore area in New York also had iron smelters.

The US started using less charcoal for iron smelting in 1827. That's when a furnace in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania began using anthracite coal. Blast furnaces kept using only charcoal until about 1840. Then, coke (made from coal) started to replace charcoal as the fuel. Coke is stronger than charcoal, which meant bigger furnaces could be built.

At that time, making iron and steel used more coal than iron ore. So, steel mills moved closer to coal mines to save money on transport. One problem with coke was that it had impurities like sulfur, which made the steel less good. Even though coke quickly became the main fuel, charcoal was still used to make ten percent of US iron and steel in 1884.

The Lackawanna Valley in Pennsylvania had a lot of anthracite coal and iron deposits. In 1840, brothers George W. Scranton and Seldon T. Scranton moved to the valley. They settled in a small town called Slocum's Hollow (now Scranton) to build an iron factory. Making steel using old methods was slow and very expensive.

The Scrantons used a new "hot blast method" that was developed in Scotland in 1828. This method helped get rid of impurities from the coke. The Lackawanna Ironworks became the first American company to make railroad tracks. They quickly got contracts with railroad companies across New York and Pennsylvania, building the first parts of what would become the huge US passenger railway system. The city of Scranton grew very fast and became the third-largest city in Pennsylvania. The Scrantons also tried using anthracite coal to make steel instead of charcoal or bituminous coal.

Changing from charcoal to coal for steelmaking completely changed the industry. It meant that steel factories were built near coal mines. In the 1800s, making one ton of steel needed more coal than iron ore. So, it was cheaper to build factories closer to coal mines. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was perfect for steelmaking. It was surrounded by large coal deposits and was where three rivers met, making transport easy.

Important Iron Furnaces in the Early 1800s

| Name | Location | Started | Ended |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bradys Bend Iron Company Furnaces | Armstrong County, Pennsylvania | 1840 | 1873 |

| Catherine Furnace | Newport, Page County, Virginia | 1836 | 1885 |

| Curtin Village | Centre County, Pennsylvania | 1810 | 1921 |

| Elizabeth Furnace | Fort Valley, Virginia | 1836 | 1888 |

| Georges Creek Coal and Iron Company | Lonaconing, Maryland | 1837 | 1855 |

| Isabella Furnace | Chester County, Pennsylvania | 1835 | 1894 |

| Joppa Iron Works | Baltimore County, Maryland | around 1817 | around 1865 |

| Longdale Furnace Historic District | Clifton Forge, Virginia | 1827 | |

| Mount Savage Iron Works | Mount Savage, Maryland | 1837 | around 1870 |

| Nassawango Iron Furnace Site | Snow Hill, Maryland | 1830 | 1849 |

| Richmond Furnace Historical and Archeological District | Richmond, Massachusetts | 1829 | 1923 |

| Roaring Run Furnace | Eagle Rock, Virginia | 1832 | |

| Scranton Iron Furnaces | Scranton, Pennsylvania | 1848 | 1902 |

| Tredegar Iron Works | Richmond, Virginia | 1837 | around 1950 |

Fast Growth of Steel, 1856-1940

In 1856, an Englishman named Henry Bessemer invented the Bessemer process. This new method allowed steel to be made in huge amounts from melted pig iron. It cut the cost of making steel by more than half! The first American steel mill to use this process was built in 1865 in Troy, New York.

In 1875, the biggest steel mill yet, the Edgar Thomson Steel Works, was built near Pittsburgh. It used the Bessemer process and was funded by the famous businessman Andrew Carnegie.

The huge iron ore deposits around Lake Superior were far from coal mines. So, the ore was shipped to ports on the southern Great Lakes. These ports were closer to the coal mines in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Large, complete steel mills were built in cities like Chicago, Detroit, Gary, Indiana, Cleveland, and Buffalo, New York. These mills were built to process the ore from Lake Superior.

Cleveland's first blast furnace was built in 1859. By 1860, the steel mill had 374 workers. By 1880, Cleveland was a major steel producer, with ten steel mills and 3,000 steelworkers.

The city of Gary, Indiana was started in 1906 by the United States Steel Corporation. It was built to support the large Gary Works steel plant.

The Lackawanna Steel Company built a big steel factory near Buffalo. It started making steel from Lake Superior ore in 1903. The company had made steel in Scranton, Pennsylvania since 1840. But they moved to be closer to iron ore and to try to avoid problems with workers.

Birmingham, Alabama became a major steel producer in the late 1800s. It used coal and iron ore that were mined right there. The iron ore came from a rock layer called the Red Mountain Formation.

Important Steel Furnaces from the Late 1800s (No Longer Operating)

| Name | Owners | Location | Started | Ended |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antrim Iron Company | Mancelona, Michigan | 1886 | 1945 | |

| Bellefonte Furnace | Bellefonte, Pennsylvania | 1888 | 1910 | |

| Bethlehem Works | Bethlehem Steel | Bethlehem, Pennsylvania | 1857 | 1995 |

| Brierfield Furnace | Brierfield, Alabama | 1861 | 1894 | |

| Callie Furnace | Glen Wilton, Virginia | around 1873 | 1884 | |

| Cornwall Furnace | Cedar Bluff, Alabama | around 1862 | 1874 | |

| Endor Iron Furnace | Cumnock, North Carolina | 1861 | 1971 | |

| Fayette Historic State Park | Fayette, Michigan | 1867 | 1891 | |

| Homestead Steel Works | Carnegie Steel, US Steel | Homestead, Pennsylvania | 1881 | 1986 |

| Janney Furnace Park | Ohatchee, Alabama | 1863 | 1864 | |

| Nittany Furnace | Centre County, Pennsylvania | 1888 | 1911 | |

| Oregon Iron Company | Lake Oswego, Oregon | 1867 | 1893 | |

| Sloss Furnace | Birmingham, Alabama | 1882 | 1971 | |

| South Works | US Steel | Chicago, Illinois | 1857 | 1992 |

| Sparrows Point, Maryland | Bethlehem Steel | Baltimore County, Maryland | 1889 | 2012 |

Steel During and After World War II

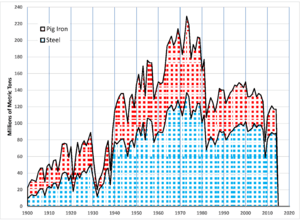

The United States iron and steel industry became super important during and right after World War II. This was because it was the only major steel maker that wasn't damaged by the war. In 1945, the US made 67% of the world's pig iron and 72% of its steel. To compare, in 2014, the US made only 2.4% of the world's pig iron and 5.3% of its steel.

Even though the US iron and steel production kept growing through the 1950s and 1960s, the rest of the world's steel industry grew much faster. So, the US share of world production got smaller. In the 1960s, the US started buying a lot of steel from other countries, especially Japan.

Changes in the Late 1900s

US production of iron and steel reached its highest point in 1973. The industry made a total of 229 million metric tons of iron and steel. But US iron and steel production dropped a lot during the economic downturn of the late 1970s and early 1980s. From 203 million tons in 1979, US production almost halved to 107 million tons in 1982.

Some steel companies went out of business, and many steel plants closed for good. By 1989, US iron and steel production went back up to 142 million tons, but this was still much lower than in the 1960s and 1970s.

People disagree about why this sudden decline happened. Some reasons suggested include:

- Other countries selling steel in the US for very low prices.

- High costs for workers.

- Poor management.

- Unfair tax rules.

- Costs for environmental protection.

One study found that the huge drop in jobs wasn't just because foreign steel was replacing US steel. In fact, the amount of US steel sold in 2005 was similar to the early 1960s. But the number of jobs in the US steel industry had dropped by about 75% in that same time. Instead, most of the job losses were due to new technology and better ways of making steel. This included a shift from big, old-style steel plants to smaller "mini mills".

Cleveland had nine big steel mills in the 1970s. US Steel closed one mill in 1979 and then shut down its six other Cleveland mills in 1984. Cleveland's last two steel companies, Republic Steel and Jones & Laughlin, joined together to form LTV Steel in 1984. LTV Steel went out of business in 2000. The factory, which is on both sides of the Cuyahoga River, is Cleveland's only remaining large steel mill. It is now owned by Cleveland Cliffs.

In the Pittsburgh area, factory closures led to a very high unemployment rate. It reached 17.1% in January 1983, and in some places like Beaver County, it was as high as 27.1%. Between 1970 and 1990, the Pittsburgh region lost 30% of its people.

Modern Steel Industry Changes

The number of very large steel mills has continued to go down. In 2014, only 11 such mills were still working in the US. Most of the steel made now comes from the growing number of mini-mills, also called specialty mills. In 2014, there were 113 of these. In 1981, mini-mills made about 15% of US steel. Since 2002, steel made using an electric arc furnace (the process mini-mills use) has made up more than half of all steel produced in the US. Many companies that run large mills also have mini-mills.

Between 2000 and 2014, several companies went out of business or were bought by others. This changed the trend of the industry becoming more spread out. In 2000, the top three steelmakers (Nucor, US Steel, and Bethlehem Steel) made 28% of the steel. The top ten made 58%. By 2014, the top three (Nucor, ArcelorMittal, and US Steel) made 56% of the steel, and the top ten made 87%.

Important Steel Furnaces from the 1900s (No Longer Operating)

| Name | Owners | Location | Started | Ended |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duluth Works | US Steel | Duluth, Minnesota | 1915 | 1987 |

| Fontana blast furnace | Kaiser Steel | Fontana, California | 1942 | around 1982 |

| Geneva Steel mill | US Steel | Vineyard, Utah | 1944 | 2001 |

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |