Ulysses S. Grant and the American Civil War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ulysses S. Grant and the American Civil War

|

|

|---|---|

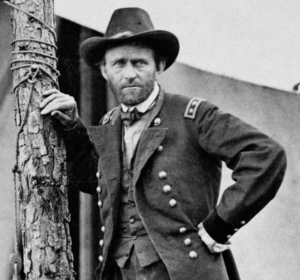

General Grant

|

|

| Commanding General of the United States Army | |

| In office March 9, 1864 – March 4, 1869 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Hiram Ulysses Grant

April 27, 1822 Point Pleasant, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | July 23, 1885 (aged 63) Wilton, New York, U.S. |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1869 |

| Rank | |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

Ulysses S. Grant was a famous general for the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was also elected president twice. Grant started his military journey at West Point in 1839. After graduating, he served bravely as a lieutenant in the Mexican–American War. He learned a lot about battle plans from Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott.

After that war, Grant worked at different army posts. He had to leave the army in 1854. He tried farming but it didn't work out. When the Civil War began in April 1861, Grant was working in his father's leather store. His military skills were greatly needed. A politician named Elihu B. Washburne helped him get promoted.

Grant trained new Union soldiers and became a Colonel in June 1861. Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont saw Grant's strong will to win. He made Grant the commander of the District of Cairo. Grant became famous across the country after capturing Fort Donelson in February 1862. President Abraham Lincoln then promoted him to Major General.

After important battles and victories at Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga, President Lincoln promoted Grant again. In 1864, he became a Lieutenant General. He was put in charge of all Union Armies. Grant then defeated Robert E. Lee after tough battles in the Overland Campaign, Petersburg, and Appomattox.

After the Civil War, Grant received his final promotion to General of the Armed Forces in 1866. He served until 1869. His popularity as a war hero helped him get elected as the 18th President of the United States for two terms. Some historians praise Grant for his "military genius." They see him as a strong leader who focused on movement and supplies. He is seen as a modern and skillful general. He led from a central command post and used common sense. Grant also delivered well-planned attacks on enemy armies.

Contents

- Ulysses S. Grant: A Civil War Hero

- Starting His Military Career

- Early Battles: Belmont, Fort Henry, and Fort Donelson

- The Bloody Battle of Shiloh

- Helping Former Slaves

- The Battle for Vicksburg

- Victory at Chattanooga

- Becoming General-in-Chief

- The Overland Campaign: A Tough Fight

- Public Opinion and Challenges

- Petersburg and Appomattox: The Final Push

- Grant's Legacy and Later Life

- Military Ranks and Dates

- Grant's Western Commands (1861-1863)

- Casualties in Grant's Campaigns

- Images for kids

Ulysses S. Grant: A Civil War Hero

Starting His Military Career

On April 15, 1861, the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter. President Abraham Lincoln asked for 75,000 volunteers to stop the rebellion. People in Galena, Illinois, were excited to help. They knew Grant had a lot of military experience. Grant helped gather volunteers in Galena. He went with them to Springfield, the state capital.

There, new army units were very disorganized. With help from Congressman Elihu B. Washburne, Governor Richard Yates asked Grant to train the volunteers. Grant was very good at training soldiers. He wanted to lead troops in battle. So, Yates made him a colonel in the Illinois militia. On June 17, he took command of the 21st Illinois Infantry. This group was not very disciplined. He went to Mexico, Missouri, to protect the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad from Confederate attacks.

On July 31, 1861, President Lincoln made him a brigadier general. On September 1, Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont chose him to lead the District of Southeast Missouri. Grant set up his main office in Cairo, Illinois. This is where the Ohio River meets the Mississippi. His command was soon renamed the District of Cairo.

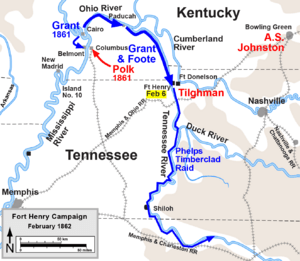

Early Battles: Belmont, Fort Henry, and Fort Donelson

Grant's first Civil War battles happened while he led the District of Cairo. The Confederate Army was in Columbus under General Leonidas Polk. They had broken Kentucky's neutrality. Grant quickly took action and seized Paducah, Kentucky, on September 5, 1861.

His commander, Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont, told him only to make a show of force. He was not to attack Polk directly. Grant followed this order until President Lincoln removed Frémont on November 2, 1861. Grant then went on the attack. He took 3,000 Union troops by boat. On November 7, 1861, he attacked the Confederate Army at Belmont, Missouri. General Gideon J. Pillow led the Confederates there.

Grant's troops first pushed back the Confederates. But his volunteers celebrated too early instead of continuing the fight. Pillow received more troops from Polk. This forced the Union soldiers to retreat quickly. Even though the battle didn't have a clear winner, Grant and his troops gained confidence. More importantly, President Lincoln noticed Grant's willingness to fight.

Grant got permission to attack Confederate Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. He went with Admiral Andrew H. Foote's naval ships. The expedition sailed south on February 3, 1862. They had two divisions of 15,000 men. The river had risen during winter, flooding some of Fort Henry's defenses. On February 6, 1862, Admiral Foote's Union fleet attacked Fort Henry. Grant's troops began landing. The fort surrendered before Grant could even attack. Two Union naval officers went into the fort to accept the surrender. About 3,000 Confederates escaped east before the surrender. But the fall of Fort Henry opened the way for the Union in Tennessee and Alabama.

After Fort Henry, Grant moved his army 12 miles east. He wanted to capture Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Foote's naval fleet arrived on February 14. They immediately started bombarding the fort. However, Fort Donelson's guns near the water fought back well. They pushed back the naval fleet.

On February 15, Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd ordered General Pillow to attack Grant's Union forces. The goal was to create an escape route to Nashville, Tennessee. Pillow's attack pushed back one of Grant's corps. But the Confederate advance stopped. Grant was able to rally his troops. He kept the Confederates from escaping. The Confederate forces, led by General Simon Bolivar Buckner, finally surrendered Fort Donelson on February 16. Grant's demand for surrender became famous: "No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted." From then on, people called him "Unconditional Surrender" Grant. President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to major general of volunteers.

The surrender of Fort Donelson was a huge victory for the Union. They captured 12,000 Confederate soldiers and many weapons. After this, Grant became known for smoking cigars, sometimes 18-20 a day.

The Bloody Battle of Shiloh

In early March 1862, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck ordered Grant's Army of the Tennessee to move south. They were to attack Confederate railroads. Halleck then told Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell's Army of the Ohio to join Grant. They planned to attack Confederate troops in Corinth, Mississippi. Buell's army was only 90 miles east. But he was slow to send help, saying "swollen rivers" were in the way.

Union commanders Grant and Brig. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman thought the Confederates would not attack. So, they did not build defenses. On April 6, 1862, the Confederates launched a surprise attack. This was the Battle of Shiloh. Their goal was to destroy Grant's forces before Buell's army arrived. Over 44,000 Confederate troops attacked Grant's army. They were led by Albert Sidney Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard. The Union troops were camped nine miles north of Savannah, Tennessee, at Pittsburg Landing.

Union Col. Everett Peabody's soldiers found the Confederates coming. He warned the Union Army to get ready. Still, the Confederates pushed back the Union Army at first. Some Union soldiers, led by Brig. Gens. Benjamin Prentiss, W. H. L. Wallace, and James M. Tuttle, fought bravely. They held off strong Confederate attacks for seven hours. This area was called the "Hornet's Nest." This gave the Union army time to get their lines straight and gather more troops. Prentiss was captured, and Wallace was badly wounded.

Grant, who was recovering from a horse fall, arrived from Savannah. He and Sherman rallied the troops and prevented defeat. Even though Grant's forces were beaten up, they held strong positions. They had 50 artillery guns. Two Union gunboats fired at the Confederates. Grant received more troops from Buell and his own army. He had 45,000 troops in total. On April 7, he launched a counter-attack. Confederate General Johnston was killed on the first day. The Confederate Army, now led by Beauregard, was outnumbered. They were forced to retreat to Corinth, Mississippi.

The Battle of Shiloh had 23,746 casualties. This shocked both sides. President Lincoln refused to fire Grant. He said, "I can't spare this man; he fights." After Shiloh, General Halleck took command of a 120,000-man army. This included Grant's army. Halleck made Grant his second-in-command. Grant was unhappy and thought about leaving. But his friend, William Tecumseh Sherman, convinced him to stay. After capturing Corinth, Mississippi, the large army was broken up. Halleck was promoted and moved to Washington, D.C. Grant took back command of the Army of the Tennessee. A year later, he captured the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg.

Helping Former Slaves

On July 2, 1862, President Lincoln allowed African American "fugitive slaves" to join the Union Army. In late 1862, Grant worked to help many black slave refugees. They were in Western Tennessee and Northern Mississippi. On November 13, 1862, Grant put Chaplain John Eaton in charge of these refugees. Eaton set up camps and had the refugees work on empty plantations. They harvested corn and cotton.

Eaton was a fair leader. He protected the refugees from Confederate attackers. At first, the refugees were not paid directly. But money was used for their benefit. Later, these African Americans joined the Union Army. They were paid to cut wood for Union steamships. With this money, they could feed and clothe their families. This was the start of what would become the Freedmen's Bureau after the war. Similar efforts to include African Americans in the war happened on the Atlantic coast. On January 1, 1863, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This freed slaves in states that were rebelling. After this, the Union recruited both former slaves and other black people. They fought against the Confederacy in new regiments called the United States Colored Troops.

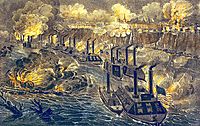

The Battle for Vicksburg

President Lincoln wanted to control the Mississippi River. So, the Union Army and Navy decided to capture the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg in 1862. Lincoln allowed Maj. Gen. John Alexander McClernand to gather troops for an attack on Vicksburg. A rivalry grew between Grant and McClernand. Both wanted credit for taking Vicksburg.

The Vicksburg campaign began in December 1862. It lasted six months before the Union Army finally captured the fortress. The campaign involved many naval actions and troop movements. It had two main parts. Capturing Vicksburg would divide the Confederacy into two parts. At the start, Grant tried to capture Vicksburg by land from the Northeast. But Confederate Generals Nathan B. Forrest and Earl Van Dorn stopped him. They raided Union supply lines. A direct river attack also failed when Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman was pushed back at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou.

In January 1863, McClernand and Sherman's armies defeated the Confederates at Arkansas Post. Grant tried five times to capture Vicksburg by water. All attempts failed. With the Union needing a victory, the second part of the Vicksburg campaign began in March 1863. Grant marched his troops down the west side of the Mississippi River. They crossed over at Bruinsburg. Admiral David Dixon Porter's navy ships had already sailed past Vicksburg's guns on April 16, 1863. This allowed Union troops to cross to the east side of the river. Grant used clever plans to hide his movements from the Confederates.

After crossing, Grant moved his army inland. After several battles, the state capital, Jackson, Mississippi, was captured. Confederate general John C. Pemberton was defeated by Grant's forces. This happened at the battles of Champion Hill and Black River Bridge. Pemberton retreated to the Vicksburg fortress. After two costly attacks on Vicksburg failed, Grant began a 40-day siege. Pemberton could not join forces with another Confederate army. So, he finally surrendered Vicksburg on July 4, 1863.

Battle of Champion Hill

Sketched by Theodore R. Davis.

Capturing Vicksburg was a major turning point for the Union. The surrender of Vicksburg and the defeat of Confederate general Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg were big losses for the Confederacy. The Union now controlled the Mississippi River, splitting the Confederacy in two. President Lincoln promoted Grant to Major General in the Regular Army. Vicksburg was the second time a Confederate army surrendered to Grant. During the Vicksburg siege, Grant removed McClernand from command. McClernand had published an order that seemed to take all the credit for the campaign. McClernand appealed to President Lincoln, but it didn't help. Grant had ended their rivalry. The Union army captured many Confederate weapons and supplies. The total casualties for the Vicksburg operation were 10,142 for the Union and 9,091 for the Confederacy.

During the Vicksburg campaign, Grant faced issues with traders. He issued an order on December 17, 1862, to deal with trade violations. This order caused protests. President Lincoln canceled the order on January 4, 1863.

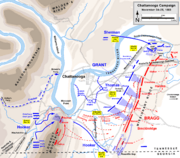

Victory at Chattanooga

When Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans was defeated at Chickamauga in September 1863, the Confederates, led by Braxton Bragg, surrounded the Union Army in Chattanooga. President Lincoln put Grant in charge of the new Military Division of the Mississippi. This made Grant the commander of all Western Armies. Grant immediately removed Rosecrans from duty. He went to Chattanooga to take control. He brought 20,000 troops from the Army of the Tennessee. Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker was also ordered to Chattanooga. He brought 15,000 troops.

Food and supplies were very low for the Union army in Chattanooga. They needed help to prepare for a counter-attack. When Grant arrived, he learned about their problems. He started a supply system called the "Cracker Line." This was designed by Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas's engineer. After the Union army took Brown's Ferry, Hooker's troops and supplies entered the city. This helped feed the starving men and animals. It also prepared them for an attack on the Confederates surrounding the city.

On November 23, Grant launched his attack on Missionary Ridge. He combined forces from three Union armies. Maj. Gen. Thomas took a small hill called Orchard Knob. Maj. Gen. Sherman took positions to attack Bragg's right side on Missionary Ridge. On November 24, in heavy fog, Hooker captured Lookout Mountain. He positioned his troops to attack Bragg's left side.

On November 25, Grant ordered Thomas's army to make a small attack. They were only supposed to take the "rifle pits" on Missionary Ridge. But after taking the pits, the soldiers kept going. They charged straight up Missionary Ridge without orders. Bragg's army was defeated and scattered by this frontal assault. They were forced to retreat. Grant was surprised at first because he didn't order the charge. But he was happy with the successful outcome. The victory at Missionary Ridge removed the last Confederate control of Tennessee. It opened the way for an invasion of the Deep South. This led to Sherman's Atlanta campaign in 1864. After the battle, the Union had 5,824 casualties, and the Confederates had 6,667.

Becoming General-in-Chief

After the Confederate defeat at Chattanooga, President Lincoln promoted Grant. He became a Lieutenant General on March 2, 1864. This was a special rank. Only George Washington had held it fully before. Lincoln was careful about giving this promotion. He only did so after learning Grant was not planning to run for president in 1864.

With his new rank, Grant moved his main office to the East. He made Maj. Gen. Sherman the Commander of the Western Armies. President Lincoln and Grant met in Washington. They planned a "total war" strategy. This meant attacking the Confederacy's military, railroads, and economy.

African Americans were now trained soldiers in the Union Army. This also took away the Confederacy's labor force. The two main goals were to defeat Robert E. Lee's Army of Virginia and Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee. They would attack the Confederacy from many directions. The Union Army of the Potomac, led by George Meade, would attack Lee's army. Benjamin Butler would attack south of Richmond. Sherman would attack Johnson's army in Georgia. Other generals would destroy railroad lines. Grant would command all Union forces while in the field with Meade.

The Overland Campaign: A Tough Fight

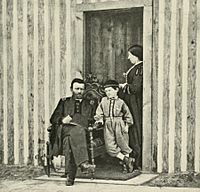

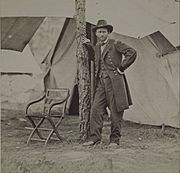

Photographed by Mathew Brady in 1864.

On May 4, 1864, Grant began a series of battles with Robert E. Lee. This was called the Overland Campaign. The first battle was in a thick forest known as the Wilderness. Lee used the dense trees to fight Grant's larger army. Union Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock's corps pushed back Confederate General A. P. Hill's corps. But Lee brought in reserves and pushed the Union back. The battles were difficult and bloody. They lasted two days, May 5 and 6. Neither side won a clear victory.

Unlike other Union generals, Grant did not retreat. He kept moving around Lee's right side, heading south. The Wilderness battle had many casualties. The Union lost 17,666 men, and the Confederates lost 11,125.

Even though the Wilderness battle was costly, Grant decided to keep fighting Lee. As the Union army moved south, Grant faced an even tougher battle. This was a 14-day fight at Spotsylvania. Lee had moved his army to Spotsylvania Court House before Grant arrived. The battle started on May 10. Lee's army was in an exposed shape called the "Mule Shoe." But they fought off many Union attacks for six days.

The fiercest fighting was at a spot called "Bloody Angle." Rifles wouldn't fire because gunpowder got wet. Soldiers fought hand-to-hand, like in ancient times. Many soldiers on both sides were killed. By May 21, the fighting stopped. Grant had lost 18,000 men. Lee's army was also badly damaged, losing 10,000 to 13,000 men. During the fighting, Grant said, "I will fight it on this line if it takes all summer."

Grant couldn't break Lee's defenses at Spotsylvania. So, he moved south again, closer to Richmond. Grant tried to make Lee fight in the open. But Lee guessed Grant's move. He retreated to the North Anna River. Many Confederate generals, including Lee, were sick or injured. Lee was too sick to take advantage of chances to attack the Union army. After some small battles at North Anna on May 23 and 24, the Union army moved to Cold Harbor.

From June 1 to 3, Grant and Lee fought at Cold Harbor. The Union had the most casualties on the last day. Grant's attack on June 3 was a disaster. The Union lost 6,000 men, while Lee lost only 1,500. After twelve days at Cold Harbor, the Union had 12,000 casualties, and the Confederates had 2,500. On June 11, 1864, Grant's army broke away from Lee. On June 12, they secretly crossed the James River. They then attacked the railroad junction at Petersburg. For a short time, Robert E. Lee didn't know where the Union army was.

Public Opinion and Challenges

After the tough fighting at Cold Harbor, some people in the North called Grant a "Butcher." They said he caused too many deaths without a clear victory over Robert E. Lee. However, Grant had stopped Lee's ability to attack. He had trapped Lee in the trenches of Petersburg. Grant himself regretted the attack on June 3 at Cold Harbor. He decided to keep casualties low after that. Grant wanted to keep fighting, and Lincoln supported him.

Without a Union victory, President Lincoln's re-election campaign in 1864 was at risk. Maj. Gen. Sherman was stuck chasing a Confederate general. Other Union generals were also having trouble. The Union war effort seemed to be slowing down in the summer of 1864. Washington D.C. was even exposed to Confederate attack. Some anti-war Democrats wanted to recognize the Confederacy and make peace. They also encouraged people to avoid the draft.

Petersburg and Appomattox: The Final Push

Petersburg was a key supply center for the Confederates. It had five railroads meeting there. Capturing it meant Richmond would fall quickly. To protect Richmond and fight Grant, Lee had left Petersburg with few troops. After crossing the James River, the Union army marched towards Petersburg. Grant sent troops to capture Petersburg, which was lightly guarded by Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard. Grant set up his headquarters at City Point for the rest of the war.

Union forces quickly took Petersburg's outer trenches on June 15. However, the Union commander stopped fighting. He waited until June 16 to attack the city. This allowed Beauregard to bring in more troops. The second Union attack on Petersburg lasted until June 18. Lee's veteran soldiers finally arrived. They stopped the Union army from taking the important railroad junction. Unable to break Lee's defenses, Grant began a siege.

Lee realized Washington was unprotected. He sent troops under Lieutenant General Jubal Early north. He hoped this would force the Union to send forces after Early. Early marched through the Shenandoah Valley. He defeated a Union general and reached the edge of Washington. This caused great alarm. Lincoln urged Grant to send veteran Union troops to the capital. Early could not take the city.

At Petersburg, Grant tried a new tactic. He blew up a section of Lee's trenches. Union coal miners dug a huge tunnel and planted gunpowder. The explosion created a large crater. This opened a big gap in the Confederate line. But the Union attack that followed was slow and disorganized. Troops gathered inside the crater. This allowed Lee to push them back.

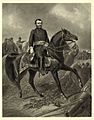

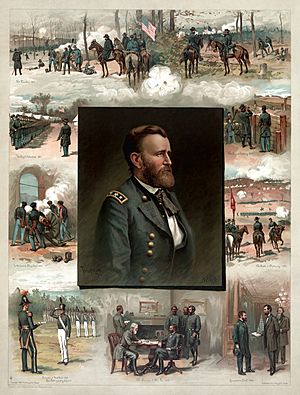

Lt. Gen. Grant meeting with President Lincoln, R. Adm. Porter, and Maj. Gen. Sherman.

G.P.A. Healy 1868

Despite this setback, Grant kept Lee's army trapped at Petersburg. Grant's siege allowed the Union war effort on other fronts to succeed. Sherman took Atlanta on September 2, 1864. He then began his March to the Sea in November. With victories at Atlanta and Mobile Bay, Lincoln was re-elected President. The war continued. On October 19, Philip Sheridan defeated Early's army. Sheridan and Sherman followed Lincoln and Grant's strategy of total war. They destroyed the economic resources of the Shenandoah Valley and large parts of Georgia and the Carolinas. On December 16, Maj. Gen. George Henry Thomas defeated Confederate general John Bell Hood at Nashville. Grant continued to extend the Petersburg siege line. He wanted to capture vital railroad lines that supplied Richmond. This stretched Lee's defenses very thin.

In March 1865, Grant invited Lincoln to his headquarters in Virginia. Sherman also happened to be visiting at the same time. This was the only time Lincoln, Grant, and Sherman met together. This meeting was captured in a famous painting called The Peacemakers. Grant continued to pressure Lee's army at Petersburg. Lee was forced to leave Richmond in April 1865. After a nine-day retreat, Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

This was considered Grant's greatest triumph. It was the third time a Confederate Army surrendered to him. Grant offered generous terms to Lee. These terms helped ease tensions between the armies. They also helped preserve some Southern pride. This was important for reuniting the country. Within a few weeks, the American Civil War was over.

Grant's Legacy and Later Life

Ulysses S. Grant was very popular in the United States after the Civil War. After President Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, Grant became America's first four-star general. He helped Congress with their efforts to rebuild the South. Grant often disagreed with President Andrew Johnson's ideas during this time. Grant was seen as a national leader who could heal the country. He helped remove the French from Mexico. He also stopped a group called the Fenian Brotherhood from trying to take over Canada. Grant was also in charge of army campaigns against Native American tribes in the West.

Grant was elected President twice, in 1868 and 1872. His time in office had some problems with government corruption. There was also violence over the rights of African Americans. As President, Grant supported Congress's efforts to protect the Civil Rights of African Americans. For a few years, he was able to legally and militarily defeat the Ku Klux Klan.

After his presidency, Grant went on a long trip around the world. He visited Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. He returned to San Francisco in June 1879. In March 1885, President Chester A. Arthur allowed Grant to rejoin the U.S. military. This meant he could receive retirement pay. President Grover Cleveland later fully reinstated his rank. This gave Grant and his family much-needed military retirement pay. In 1885, Grant finished writing his popular and successful military memoirs. He died after a difficult struggle with throat cancer.

Later, some groups in the South promoted Robert E. Lee as the greatest general of the Civil War. They tried to make Lee seem more important than Grant. This idea spread throughout American society. Grant was sometimes unfairly seen as someone who won only because he fought a brutal war. However, historian Edward H. Bonekemper argues that Grant was the most successful general of the Civil War. He points out that in the West, Grant drove the Confederates out of the Mississippi Valley. He did this through battles like Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga. When Grant took command of the Union Army in the East, he defeated Lee's Confederate army within a year. This effectively ended the war. According to Bonekemper, Grant's armies caused more casualties to the Confederates than they received.

Military Ranks and Dates

| Insignia | Rank | Date | Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| No insignia | Cadet, USMA | 1 July 1839 | Regular Army |

| Brevet Second Lieutenant | 1 July 1843 | Regular Army | |

| Second Lieutenant | 30 September 1845 | Regular Army | |

| Brevet First Lieutenant | 8 September 1847 | Regular Army | |

| First Lieutenant | 16 September 1847 | Regular Army | |

| Captain | 5 August 1853 | Regular Army (Resigned 31 July 1854.) |

|

| Colonel | 17 June 1861 | Volunteers | |

| Brigadier General | 7 August 1861 | Volunteers (To rank from 17 May 1861.) |

|

| Major General | 16 February 1862 | Volunteers | |

| Major General | 4 July 1863 | Regular Army | |

| Lieutenant General | 4 March 1864 | Regular Army | |

| General | 25 July 1866 | Regular Army | |

| Source: | |||

Grant's Western Commands (1861-1863)

- Army and Department of the Tennessee Brigadier General – August 1, 1861, to February 14, 1862

- District and Army of West Tennessee Major General – February 21 to October 16, 1862

- Department and Army of the Tennessee Major General – October 16, 1862, to October 24, 1863

Casualties in Grant's Campaigns

Western Campaigns and Battles:

- Union casualties under Grant: 36,688

- Confederate casualties: 84,187

Eastern Campaigns and Battles:

- Union casualties under Grant: 116,954

- Confederate casualties: 106,573

Total Casualties (Western and Eastern):

- Total Union casualties under Grant: 153,642

- Total Confederate casualties: 190,760

- Difference (Confederate vs. Union): 37,118

-

- Note: This includes soldiers killed, wounded, missing, or captured.

Images for kids