History of Cornwall facts for kids

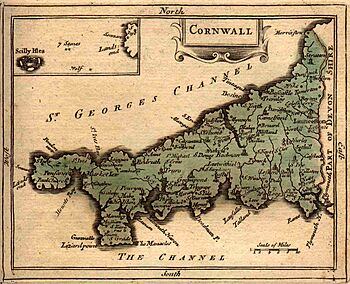

The history of Cornwall stretches back to the Stone Age, when early humans first visited the area. People have lived here continuously for about 10,000 years, ever since the last ice age ended. When written history began around 2,000 years ago, people in Cornwall spoke an ancient language called Common Brittonic. This language later changed into Cornish. Cornwall was part of a larger area called Dumnonia, which also included modern-day Devon and parts of Somerset.

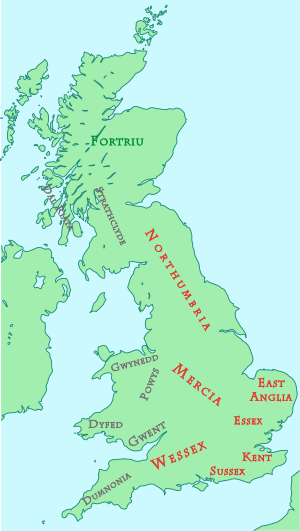

After the Roman Empire ruled for a while, Cornwall went back to being led by its own independent British leaders. It stayed connected to places like Brittany in France, Wales, and southern Ireland across the Celtic Sea. Eventually, the kingdom of Dumnonia broke up, and Cornwall faced conflicts with its powerful neighbour, Wessex.

By the mid-800s, Wessex had taken control of Cornwall, but Cornwall still kept its unique culture. In 1337, the English king created the title Duke of Cornwall. This title is always given to the king's oldest son and future heir. Cornwall, along with Devon, had special laws called Stannary laws that gave them some control over their important tin mining industry. However, by the time of King Henry VIII, England was becoming more centralized. This meant Cornwall lost most of its special independence. There were even rebellions, like the Cornish Rebellion of 1497 and the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549, where Cornish people fought against the English government.

By the late 1700s, Cornwall was fully part of the Kingdom of Great Britain, just like the rest of England. The Cornish language started to disappear quickly. The Industrial Revolution brought big changes, especially with the rise of Methodism which made many Cornish people Protestant but not part of the official Church of England. When tin mining declined, many Cornish people moved overseas, creating the Cornish diaspora. This also led to a renewed interest in Cornish culture and language, sparking the Celtic Revival and Cornish revival. This eventually led to the start of Cornish nationalism in the late 1900s.

Cornwall's early history, especially mentions of a Cornish King named Arthur in old Welsh and Breton stories, inspired famous legends. These include Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, which came before the well-known Arthurian legends.

Contents

Ancient Cornwall: From Stone Age to Iron Age

Life in the Stone Age

Cornwall was not always lived in during the very early Stone Age. But around 10,000 years ago, after the last ice age, people returned. These early people were hunter-gatherers, meaning they hunted animals and gathered plants for food. We have a lot of evidence that they lived here.

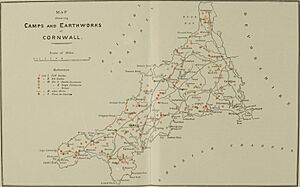

The higher areas of Cornwall were the first places people settled. This was because there weren't many trees to clear. Many large stone monuments, called megaliths, were built during the later Stone Age. Cornwall has more prehistoric remains than almost any other English county. These include tall standing stones called menhirs, burial mounds called barrows, and old hut circles where people lived.

The Bronze Age and Tin Mining

Cornwall and its neighbour, Devon, had huge amounts of tin. People started mining this tin a lot during the Bronze Age. Tin is super important because you need it to mix with copper to make bronze. Around 1600 BCE, the West Country (Cornwall and Devon) became very rich. This was because they exported tin all over Europe. This wealth helped create beautiful gold ornaments found at Wessex culture sites. Even tin bars found in shipwrecks from 1200 BCE off the coast of modern Israel have been traced back to Cornwall!

The Iron Age and Celtic People

Around 750 BCE, the Iron Age arrived in Britain. Iron tools, like plows and axes, made farming much easier. This was also when many hill forts were built. Around the same time, Celtic cultures and people spread across the British Isles.

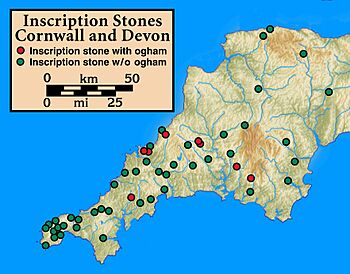

During the British Iron Age, Cornwall, like most of Britain, was home to Celts known as the Britons. The Celtic language they spoke, Common Brittonic, eventually became different languages, including Cornish.

The first written account of Cornwall comes from a Greek historian named Diodorus Siculus. He wrote about the 4th-century BCE explorer Pytheas, who sailed to Britain:

The people of Belerion (which is Land's End in Cornwall) are civilized because they trade with foreign merchants. They carefully prepare the tin they find... Merchants buy the tin from the locals and take it to Gaul (modern France). After about thirty days of travel by land, they finally bring their goods on horses to the mouth of the Rhône River.

Some people used to believe that the Phoenicians traded directly with Cornwall for tin. However, there is no archaeological proof of this. Modern historians have shown that these old ideas about a "Phoenician legacy" in Cornwall are not true.

Where the Name Cornwall Comes From

When ancient Roman and Greek writings appeared, Cornwall was home to tribes who spoke Celtic languages. The Greeks and Romans called the very tip of Britain Belerion or Bolerium. Later, a Roman document from around 700 CE mentions Puro coronavis. This name might mean "Fort of the Cornovii." This suggests that the Cornovii tribe, who were earlier known from an area around modern Shropshire, had set up a base in the southwest by the 5th century.

This tribal name is probably where the Cornish word for Cornwall, Kernow, comes from. The English name, Cornwall, comes from this Celtic name, with the Old English word Wealas added. Wealas meant "foreigner."

Before the Romans, Cornwall was part of the kingdom of Dumnonia. Later, the Anglo-Saxons called it "West Wales" to tell it apart from "North Wales" (which is modern-day Wales).

Roman Times in Cornwall

During the time of Roman rule in Britain, Cornwall was quite far from the main Roman centers. Roman roads did extend into Cornwall, but we only know of a few important Roman sites. These include three forts: Tregear near Nanstallon, one near Restormel Castle, and one near St Andrew's Church in Calstock. A Roman-style villa was also found at Magor Farm near Camborne.

Pottery and other items suggesting an ironworks have been found near St Austell. Experts say this challenges the idea that Romans didn't settle in Cornwall. Professor Barry Cunliffe noted that "in the south-west peninsula of Devon and Cornwall, the lack of Romanization... is particularly striking." This means the local way of life continued mostly unchanged west of Exeter.

Only a few Roman milestones (stones marking distances) have been found in Cornwall. Two were found near Tintagel, one near Carn Brea, Redruth, and two near St Michael's Mount. One of these is now in Breage Parish Church. Another is in St Hilary's Church, St Hilary (Cornwall).

Archaeological sites like Chysauster Ancient Village and Carn Euny in West Penwith show a unique Cornish 'courtyard house' style of building during the Roman period. These stone houses were very different from those in southern Britain. But they were similar to buildings found in Atlantic Ireland and other parts of Europe.

After the Romans: Early Medieval and Medieval Periods

After the Romans left Britain around 410 CE, Germanic peoples like the Saxons took over most of the east of the island. But in the west, Devon and Cornwall remained as the British kingdom of Dumnonia.

Dumnonia had strong cultural connections with Christian Ireland, Wales, and Brittany (in France) through sea trade routes. There's great evidence of this trade at the old stronghold of Tintagel in Cornwall. The Breton language is actually closer to Cornish than to Welsh, showing how connected these areas were.

Cornwall and Wessex: A Long Struggle

In the early 700s, Cornwall was probably a part of Dumnonia. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that in 710, Geraint, the king of Dumnonia, fought against Ine, the king of Wessex. Another old record, the Annales Cambriae, says that in 722, the Battle of Hehil "among the Cornishmen" was won by the Britons. Some historians think this means Dumnonia had fallen by 722, and the British victory saved the new kingdom of Cornwall for another 150 years. There were many battles between Wessex and Cornwall throughout the 700s.

However, historian John Reuben Davies believes that Dumnonia ended around the early 800s. He says:

- The kingdom of Cornwall, on the other hand, remained as an independent British territory in the face of pressure from Wessex, cut off from fellow Brittonic-speakers in Wales and Brittany by the sea and the West Saxons.

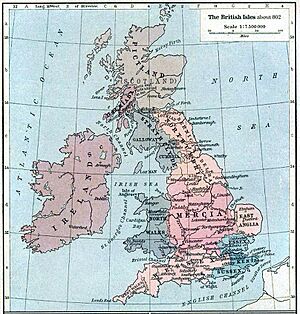

In 814, King Egbert of Wessex attacked Cornwall "from the east to the west." In 825, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says the Cornish fought the men of Devon. In 838, the Cornish, allied with Vikings, were defeated by the West Saxons at the Battle of Hingston Down. This was the last recorded battle between Cornwall and Wessex. It likely meant Cornwall lost its independence. In 875, King Dungarth of Cornwall drowned. This suggests he might have been a sub-king, meaning he ruled under Wessex.

Kenstec became the first bishop of Cornwall to promise loyalty to the Archbishop of Canterbury. Around the same time, the bishop of Sherborne was told to visit Cornwall every year to "root out the errors of the Cornish Church." These are more signs that Cornwall was becoming part of Wessex in the mid-800s. In the 880s, Alfred the Great even left some land in Cornwall in his will.

Around 927, William of Malmesbury wrote that King Æthelstan of England forced the Cornish out of Exeter and set Cornwall's eastern border at the River Tamar. Some historians think this story is unlikely because Cornwall was already under English control by then. However, others see it as the suppression of a Cornish uprising, after which the Cornish were confined beyond the Tamar, and a separate bishopric was created for Cornwall.

Cornwall then adopted Anglo-Saxon ways of organizing land, like the hundred system. But unlike Devon, Cornwall's culture didn't become English. Most people still spoke Cornish, and place names were still mostly Celtic. In 944, Æthelstan's successor, Edmund I, called himself 'King of the English and ruler of this province of the Britons'.

The Cornish Church

The centuries after the Romans left are called the 'age of the saints'. During this time, Celtic Christianity and Celtic art spread from Ireland, Wales, and Scotland. Tradition says that saints from Ireland and the children of Brychan Brycheiniog brought Christianity to Cornwall in the 400s and 500s. Cornish saints like Piran and Meriasek had religious and political influence. They were often close to local rulers, and some were even kings themselves. There was an important monastery at Bodmin.

By the 880s, more Saxon priests were being appointed to the Church in Cornwall. They controlled some church lands, which they eventually passed to the Wessex kings. However, according to Alfred the Great's will, he owned very little land in Cornwall itself.

The early organization of the Church in Cornwall is not very clear. But in the mid-800s, it was led by a Bishop Kenstec. He recognized the authority of Ceolnoth, which brought Cornwall under the control of the Archbishop of Canterbury. In the 920s or 930s, King Athelstan created a bishopric at St Germans for all of Cornwall. The first few bishops were Cornish, but from 963 onwards, they were all English. By 1050, the Cornish bishopric was merged with the diocese of Exeter.

The 11th Century and Norman Conquest

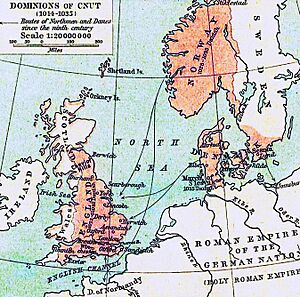

In 1013, a Danish army led by Sweyn Forkbeard conquered Wessex. Sweyn added Wessex to his Viking empire, which included Denmark and Norway. But he did not conquer Cornwall, Wales, or Scotland. These "client nations" were allowed to rule themselves in exchange for an annual payment. So, between 1013 and 1035, Cornwall was not part of King Canute the Great's territories.

The exact timeline of England's control over Cornwall is not clear. But by the time of Edward the Confessor (1042–1066), Cornwall was part of England. Records from the Domesday Book show that by this time, almost all the native Cornish landowners had lost their land. English landowners replaced them, with Harold Godwinson (who later became king) owning the most land.

The Cornish language continued to be spoken, especially in west and mid-Cornwall. It started to develop differences from its related language, Breton. Cornwall also had a very different settlement pattern from Saxon Wessex. Places continued to be named in the Celtic Cornish tradition even after 1066.

After the Norman Conquest (1066–1485)

Legend says that Condor, a survivor of the Cornish royal family, was made the first Earl of Cornwall by William the Conqueror after the Norman conquest of England. In 1068, Brian of Brittany was made Earl of Cornwall. Many other landowners in Cornwall after the Conquest were Breton allies of the Normans. These Bretons were descendants of Britons who had fled to France during the early Anglo-Saxon conquest. Earl Brian defeated a second attack in the southwest of England in 1069.

Much of the land in Cornwall was taken and given to a new Norman noble class. The largest share went to Robert, Count of Mortain, King William's half-brother. He was the biggest landowner in England after the king.

Four Norman castles were built in east Cornwall: Launceston, Trematon, Restormel, and Tintagel. A new town grew around Launceston castle, and it became the capital of the county. Over the centuries, noblemen were made Earl of Cornwall, but their families often died out. In 1336, Edward, the Black Prince was named Duke of Cornwall. This title has been given to the king's eldest son since 1421.

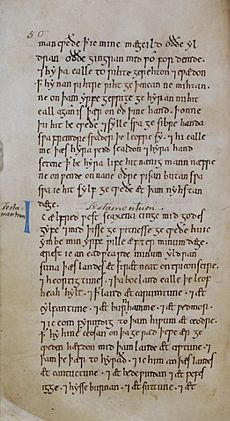

A popular Cornish literature, especially religious mystery plays, appeared in the 1300s. These were often performed at Glasney College, which was set up by the Bishop of Exeter in the 1200s.

Norman landlords who didn't live in Cornwall were replaced by a new Cornish-Norman ruling class. These families eventually became the new rulers of Cornwall. They typically spoke Norman French, Breton-Cornish, Latin, and later English. Many became involved in the Stannary Parliament system and the Duchy of Cornwall. The Cornish language continued to be spoken.

Tudor and Stuart Times (1485–1700s)

Changes Under the Tudors

The Tudor kings wanted to centralize power, which started to reduce Cornwall's special status. For example, laws that used to apply "in England and Cornwall" (meaning Cornwall had different rules) stopped being written that way.

The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 started among Cornish tin miners. They were against King Henry VII raising taxes to fight Scotland. This tax was unfair because it caused hardship and went against a special tax exemption for Cornwall. The rebels marched on London but were defeated at the Battle of Deptford Bridge.

The Cornish also rebelled in the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549. Many people in southwest Britain rebelled against a new law that made everyone use the Protestant Book of Common Prayer. Cornwall was mostly Catholic at this time. The new law was especially disliked because the Prayer Book was only in English. Most Cornish people spoke Cornish, not English. They wanted church services to continue in Latin, even though they didn't understand it. Latin had a long tradition and didn't have the political meaning of using English. It's thought that 20% of the Cornish population died in 1549. This rebellion was a major reason why the Cornish language declined.

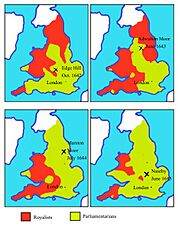

The English Civil War (1642–1649)

Cornwall played a big part in the English Civil War. It was a Royalist (King's side) area in the mostly Parliamentarian (Parliament's side) southwest. This was because Cornwall's rights and special rules were connected to the royal Duchy and Stannaries. So, the Cornish saw the King as protecting their rights. Their strong local Cornish identity also meant they would resist anyone from outside trying to interfere.

Parliamentary forces invaded Cornwall three times and burned the Duchy archives. In 1645, the Cornish Royalist leader Sir Richard Grenville, 1st Baronet made Launceston his base. He placed Cornish troops along the River Tamar and told them to keep "all foreign troops out of Cornwall." Grenville tried to use Cornish pride to get support for the King. He even suggested a plan that would have made Cornwall semi-independent.

18th and 19th Centuries: Big Changes

The 1755 Tsunami

On November 1, 1755, a huge earthquake in Lisbon, Portugal, caused a tsunami to hit the Cornish coast around 2 PM. The earthquake was about 250 miles (400 km) southwest of Lizard Point. At St Michael's Mount, the sea suddenly rose and then went back out. Ten minutes later, it rose 6 feet (1.8 m) very quickly, then went out just as fast. This rise and fall continued for five hours. The sea rose 8 feet (2.4 m) in Penzance and 10 feet (3 m) at Newlyn. The same thing happened at St Ives and Hayle. One writer from the 1700s claimed that "great loss of life and property occurred upon the coasts of Cornwall."

Tin Mining and Emigration

At one time, the Cornish were the world's best experts in mining. A School of Mines was even started in 1888. As Cornwall's tin reserves started to run out, many Cornish people moved to places like the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Their mining skills were in high demand there.

There is a popular saying that wherever you go in the world, if you see a hole in the ground, you'll find a Cornishman at the bottom of it! Several Cornish mining words are still used in English mining terms today.

After tin mining declined, along with farming and fishing, Cornwall's economy started to rely more on tourism. The area has some of Britain's most beautiful coastal scenery. However, Cornwall is still one of the poorer parts of Western Europe.

In 2019, a Canadian mining company announced it was looking to restart tin mining at South Crofty.

Religion and Administration

Cornwall and Devon saw a Jacobite rebellion in 1715. This was led by James Paynter of St. Columb. It happened at the same time as the larger "Fifteen Rebellion" in Scotland and northern England. However, the Cornish uprising was quickly stopped. James Paynter was tried for treason, but he claimed his right as a Cornish tinner. He was tried by a jury of other Cornish tinners and was found innocent.

In the 1700s, many ordinary Cornish people were either Roman Catholic or not religious. This was because they resisted the official Church of England. But in the late 1700s, Methodism was brought to Cornwall by John and Charles Wesley. Many Cornish people became Methodists. Methodism formally separated from the Church of England in 1795.

In 1841, Cornwall was divided into ten areas called hundreds. These old names are still used for some modern local government districts.

Smuggling in Cornwall

Smuggling was very common in Cornwall in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Taxes on imported goods made them expensive. So, many traders and customers avoided these taxes by using Cornwall's rugged coastline to bring in goods illegally. The most common smuggled items were brandy, lace, and tobacco from Europe. The Jamaica Inn pub on Bodmin Moor is famous for its connection to smuggling. By the 1800s, it's thought that about 10,000 people in Cornwall, including women and children, were involved in smuggling. Smuggling decreased later in the century because coastguard services improved, and taxes on imported goods were lowered.

20th and 21st Centuries: Cornish Identity Today

In the early 1900s, people started to become interested in Cornish studies again. This was thanks to the work of Henry Jenner and the creation of links with other Celtic nations.

A political party, Mebyon Kernow, was formed in 1951. Its goal was to help Cornwall and support greater self-government for the county. The party has had members elected to local councils, but not to the national parliament. However, the party is credited with making the Flag of St Piran much more widely used.

There have been some important steps in recognizing Cornish identity. In 2001, for the first time, people in the UK could choose "Cornish" as their ethnicity on the national census. In 2004, schools in Cornwall added "Cornish" as an option under "white British" on their census. On April 24, 2014, it was announced that Cornish people would be given minority status under a European agreement. This means their unique culture and identity are officially recognized and protected.

|

See also

- Timeline of Cornish history

- Constitutional status of Cornwall

- List of Cornish soldiers, commanders and sailors

- List of museums in Cornwall

General:

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |