History of Albania facts for kids

During ancient times, Albania was home to many different groups of people. These included Illyrian tribes like the Ardiaei and Taulantii. There were also Thracian and Greek tribes. Some Greek colonies were built along the coast. In the 3rd century BC, the powerful Roman Empire took over the area. It became part of Roman provinces like Dalmatia and Macedonia.

Later, the land stayed under Roman and Byzantine rule. This lasted until the Slavic migrations in the 7th century. In the 9th century, it became part of the Bulgarian Empire.

In the Middle Ages, two important states were formed: the Principality of Arbër and the medieval Kingdom of Albania. Some parts of the land also belonged to the Venetians and later the Serbian Empire. From the mid-1300s to the late 1400s, most of modern Albania was ruled by Albanian principalities. However, these fell to the fast-growing Ottoman Empire. Albania remained under Ottoman control until 1912. There were a few times when local Albanian lords gained some freedom.

The first independent Albanian state was created after the Albanian Declaration of Independence in 1912. This happened after a short occupation by Serbia. The idea of an Albanian nation grew in the late 1800s. This was part of a bigger trend of nationalism spreading across the Ottoman Empire.

A short-lived kingdom, the Principality of Albania (1914–1925), came first. Then came an even shorter-lived first Albanian Republic (1925–1928). Another kingdom, the Kingdom of Albania (1928–1939), took its place. The country was occupied by Italy just before World War II (1939–1945). After Italy made peace with the Allies, Nazi Germany occupied Albania.

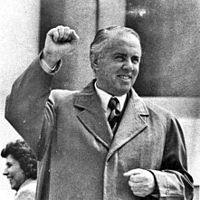

After the war, Albania became a one-party communist state. It was called the People's Socialist Republic of Albania. For most of this time, it was led by the dictator Enver Hoxha, who died in 1985. His successor, Ramiz Alia, saw the communist state fall apart in the late 1980s. This was part of the wider collapse of the Eastern Bloc.

The communist government ended in 1990. The former communist Party of Labour of Albania lost badly in elections in March 1992. This happened during a time of economic problems and social unrest. The difficult economy led many Albanians to move abroad in the 1990s. Most went to Italy, Greece, Switzerland, Germany, and North America. The crisis was worst during the Albanian Turmoil of 1997.

Things got better in the early 2000s. This allowed Albania to become a full member of NATO in 2009. The country is now trying to join the European Union.

Contents

Ancient Times

Early Human Settlements

The very first signs of humans in Albania date back to the Middle and Upper Stone Ages. These were found in Xarrë, near Sarandë, and on Mount Dajt near Tirana. In the Xarrë cave, people found tools made of flint and jasper, plus old animal bones. At Mount Dajt, bone and stone tools were found, similar to those from the Aurignacian culture.

These early finds in Albania are very much like objects from the same time found in Montenegro and northwestern Greece. Albania also has several archaeological sites with items from the New Stone Age. These date from about 6,000 BC to the end of the Early Bronze Age. Important sites include Maliq, Gruemirë, Dushman, and near Butrint.

Bronze Age Beginnings

The next period in Albania's ancient history is when Indo-European languages arrived in the Balkans. This happened because people from the Pontic steppe moved into the region. They mixed with the local Stone Age people, forming the Paleo-Balkan groups.

In Albania, groups moving from the northern parts of the region had a big impact. These groups are thought to be the ancestors of the Illyrians of the Iron Age. They arrived around the end of the Early Bronze Age. These people built tumuli (burial mounds) for their clans. Some of the first mounds date back to 2600 BC. These burial sites are similar to those found along the Adriatic coast, from the northern Balkans.

Later, in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, more groups moved into modern Albania. For example, the Bryges settled in southern Albania and northwestern Greece. Illyrian tribes moved into central Albania. The Brygian tribes' movement likely happened at the start of the Iron Age, around 1000 BC.

The Illyrians

The Illyrians were a group of tribes who lived in the western Balkans during ancient times. Their land, called Illyria by the Greeks and Romans, stretched from the Adriatic Sea in the west to the Morava River in the east. The first writings about the Illyrians come from a Greek text from the mid-4th century BC.

Many Illyrian tribes lived in the area of modern Albania. These included the Ardiaei, Taulantii, and Albanoi in central Albania. Others were the Parthini and Cavii in the north, and the Enchelei in the east. In the western parts of Albania, the Bryges, a Phrygian people, also lived. In the south, the Greek tribe of the Chaonians resided.

In the 4th century BC, the Illyrian king Bardylis united several tribes. He fought against Macedon but was defeated. Later, King Agron made the Ardiaean kingdom very powerful around 230 BC. His army and navy made it a major force in the Balkans.

Agron died suddenly around 231 BC. His wife, Queen Teuta, became ruler. She supported her people's pirate raids. After taking some cities, Teuta's forces moved into the Ionian Sea. They defeated the Greek fleets and captured the island of Corcyra. In 229 BC, she fought the Romans, starting the Illyrian Wars. These wars lasted 60 years. The Illyrians were finally defeated in 168 BC when King Gentius lost to a Roman army. After this, the Romans divided the region into three parts.

Greeks and Romans in Albania

Starting in the 7th century BC, Greek cities were built along the Illyrian coast. The most important were Apollonia, Aulon (today's Vlorë), Epidamnos (today's Durrës), and Lissus (today's Lezhë). The city of Buthrotum (today's Butrint) is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was used by Julius Caesar as a supply base in the 1st century BC.

The lands of modern Albania became part of the Roman Empire. They were part of the province of Illyricum north of the Drin River, and Roman Macedonia to the south. A major Roman road, the Via Egnatia, ran through modern Albania, ending at Dyrrhachium. Illyricum was later split into Dalmatia and Pannonia.

The Roman province of Illyricum covered much of the old Illyria. It stretched from the Drilon River in Albania to Istria in Croatia. Its capital was Salona. Southern Illyria became Epirus Nova, part of Roman Macedonia. By 395 AD, most of modern Albania was in Epirus Nova.

The Spread of Christianity

Christianity arrived in Epirus Nova, which was part of Roman Macedonia. By the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, Christianity became the main religion in the Byzantine Empire. It replaced the old pagan beliefs. The Durrës Amphitheatre was a historical place where Christianity was preached to people.

When the Roman Empire split into East and West in 395 AD, modern Albania became part of the Byzantine Empire. However, its churches were still linked to Rome. In 732 AD, the Byzantine emperor Leo III moved the churches in this area away from the Pope in Rome. He placed them under the Patriarch of Constantinople. This happened because the local archbishops supported Rome in a religious dispute.

When the Christian church officially split in 1054 (the East–West Schism), southern Albania stayed with Constantinople. Northern Albania returned to Rome's control. This was the first major religious division in the country. Later, in the 13th century, the Latin Archdiocese of Durrës was founded during Venetian rule.

Middle Ages in Albania

Early Middle Ages

After the Romans took over in 168 BC, the region became part of Epirus Nova. This was part of the Roman province of Macedonia. When the Roman Empire divided in 395 AD, modern Albania became part of the Byzantine Empire. From the 4th to 6th centuries, the region suffered attacks from groups like the Visigoths, Huns, and Ostrogoths. In the 6th and 7th centuries, Slavic invasions forced many Albanians and Vlachs into the mountains.

These invaders destroyed or weakened Roman and Byzantine cultural centers in Albania.

In the late 11th and 12th centuries, the region was important in the Byzantine–Norman wars. Dyrrhachium was a key city, being the end point of the Via Egnatia road to Constantinople. It was a main target for the Normans. By the late 12th century, the Byzantine Empire's power weakened. The region of Arbanon became an independent principality. In 1258, Sicilians took control of Corfu and the Albanian coast. This area, called the "Kingdom of Albania" in 1272, was meant to be a starting point for invading the Byzantine Empire. But the Byzantines took back most of Albania by 1274.

In the mid-9th century, most of eastern Albania became part of the First Bulgarian Empire. This area, called Kutmichevitsa, became an important Bulgarian cultural center. When the Byzantines conquered the First Bulgarian Empire, the fortresses in eastern Albania were among the last to surrender. Later, the region was taken by the Second Bulgarian Empire.

During the Middle Ages, the name Arberia was increasingly used for the region of Albania. The first clear mention of Albanians in history is from a Byzantine writer in 1079–1080. He wrote about the Albanoi taking part in a revolt against Constantinople.

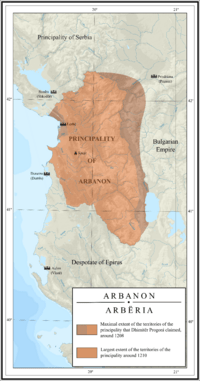

The Principality of Arbër

In 1190, the Principality of Arbër (Arbanon) was founded by a leader named Progon. It was located around the city of Krujë. Progon was followed by his sons, Gjin and Dhimitër Progoni. The principality covered parts of central Albania.

Arbanon gained full independence in 1204. This happened because Constantinople was weakened after being attacked during the Fourth Crusade. However, Arbanon lost much of its freedom around 1216. The ruler of Epirus, Michael I Komnenos Doukas, invaded northward. He took Kruja and ended the principality's independence. After Dhimitër's death, Arbanon was controlled by Epirus, then the Bulgarian Empire, and later the Empire of Nicaea.

Arbanon benefited from the Via Egnatia trade road. This brought wealth and ideas from the more advanced Byzantine civilization.

The Kingdom of Albania

After the Principality of Arber fell, the Kingdom of Albania was created by Charles of Anjou. He became King of Albania in February 1272. The kingdom stretched from Durrës south along the coast to Butrint. Charles wanted to use this kingdom as a base to invade the Byzantine Empire.

On February 21, 1272, Albanian nobles and citizens from Durrës met with Charles. He signed a treaty with them, promising to protect them and their old rights. He was named King of Albania. Charles sent many supplies to Durrës and Vlorë. This worried the Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos. He tried to convince Albanian nobles to stop supporting Charles, but they trusted Charles.

The Kingdom of Albania often fought with the Byzantine Empire. The kingdom eventually shrank to a small area around Durrës. In 1368, Karl Thopia took Durrës and created the Princedom of Albania. During this time, Catholicism spread quickly. A Western style of feudalism was also introduced, replacing the Byzantine system.

Albanian Principalities and the League of Lezhë

In 1371, the Serbian Empire broke apart. Several Albanian principalities were formed, including the Principality of Kastrioti, the Principality of Albania, and the Despotate of Arta.

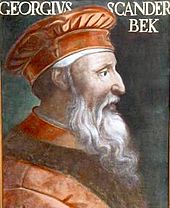

In the late 1300s and early 1400s, the Ottoman Empire conquered parts of southern and central Albania. However, Albanians took back control of their lands in 1444. This happened when the League of Lezhë was formed, led by George Kastrioti Skanderbeg, the Albanian national hero. The League was a military alliance of Albanian lords. It was created in Lezhë on March 2, 1444, to fight against the Ottoman Empire.

For 25 years, from 1443 to 1468, Skanderbeg's army of 10,000 men fought and won against larger Ottoman forces. Countries like Hungary, Naples, and Venice helped fund Skanderbeg's army. By 1450, the League had changed, and only Skanderbeg and Araniti Comino continued to fight. After Skanderbeg's death in 1468, the Ottomans easily took over Albania. However, fighting continued until the Ottoman siege of Shkodra in 1478–79. This siege ended when Venice gave Shkodra to the Ottomans in a peace treaty.

Early Ottoman Rule

Ottoman power in the western Balkans began in 1385 after their victory in the Battle of Savra. After this battle, the Ottomans created the Sanjak of Albania in 1415. This area covered conquered parts of Albania, from the Mat River in the north to Chameria in the south. In 1419, Gjirokastra became the main city of the Sanjak of Albania.

Northern Albanian nobles still had some freedom, even though they paid taxes to the Ottomans. But the southern part was directly ruled by the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans replaced many local nobles with their own landowners and introduced new taxes. This caused the people and nobles, led by Gjergj Arianiti, to revolt against the Ottomans.

At the start of the revolt, many landholders were killed or forced out. As the revolt grew, nobles whose lands had been taken joined the fight. They tried to make alliances with the Holy Roman Empire. The rebel leaders won against several Ottoman armies. However, they failed to capture many important towns in the Sanjak of Albania. Major families involved included the Dukagjini, Zenebishi, Thopia, Kastrioti, and Arianiti.

The rebels captured some towns like Dagnum. But long sieges, like the one at Gjirokastër, gave the Ottoman army time to gather large forces. They put down the main revolt by the end of 1436. The rebel leaders acted on their own, without a central plan. This lack of teamwork greatly led to their defeat. The Ottoman forces carried out many killings after the revolt.

Ottoman-Albanian Wars

Many Albanians were forced to join the Janissary army. One of them was the noble heir George Kastrioti. He was renamed Skanderbeg by his Turkish officers. After the Ottomans lost the Battle of Niš to the Hungarians, Skanderbeg left the Ottoman army in November 1443. He then started a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire.

After leaving the Ottoman army, Skanderbeg became a Christian again. He declared war against the Ottoman Empire, which he led from 1443 to 1468. Skanderbeg gathered the Albanian princes in the Venetian-controlled town of Lezhë. There, they formed the League of Lezhë. This was a military alliance of feudal lords, organized with Venetian support. Skanderbeg was chosen as the leader of the Albanian and Serbian chieftains. They united against the Ottoman Empire.

For 25 years, Skanderbeg's army of about 10,000 men fought against much larger and better-supplied Ottoman forces. They won many battles. They also held off major sieges at Krujë. Hungary, Naples, and Venice, who were once their enemies, provided money and support.

Skanderbeg defeated the Ottomans in many battles, including Torvioll and Albulena. However, he did not receive all the help promised by the popes or Italian states. He died in 1468, with no clear successor. The rebellion continued after his death, but it was not as successful. The alliances Skanderbeg had built fell apart. The Ottomans reconquered Albania, ending with the siege of Shkodra in 1479. Some parts of northern Albania remained under Venetian control. Many Albanians fled to Italy after the northern castles fell. They formed the Arbëreshë communities that still live there today.

Skanderbeg's long fight for Albania's freedom became very important to the Albanian people. It made them feel more united and aware of their national identity. It later inspired their fight for national unity, freedom, and independence.

Later Ottoman Period

When the Ottomans returned in 1479, many Albanians fled. They went to Italy, Egypt, and other parts of the Ottoman Empire and Europe. They kept their Arbëresh identity. Many Albanians became famous and wealthy as soldiers, administrators, and merchants across the Empire.

As centuries passed, Ottoman rulers lost control over local leaders. This threatened stability in the region. Ottoman rulers in the 19th century tried to regain power. They introduced reforms to control unruly leaders and stop the spread of nationalist ideas. Albania remained part of the Ottoman Empire until the early 20th century.

The Ottoman period changed the landscape of Albania. New markets, military bases, and mosques appeared in many regions. Part of the Albanian population slowly converted to Islam. Many joined the Sufi Order of the Bektashi. Becoming Muslim brought benefits, like access to Ottoman trade and jobs in the army. Many Albanians served in the elite Janissary corps and the administration.

Important Albanian figures in the Ottoman Empire included Köprülü Mehmed Pasha, the Bushati family, and Ali Pasha of Tepelena. Ali Pasha became one of the most powerful Muslim Albanian rulers in western Rumelia. He was known for his diplomatic skills, interest in modern ideas, and strict rule. His court was in Ioannina, and he governed most of Epirus and parts of northern Greece.

Albanians were very active during the Ottoman era. Leaders like Ali Pasha of Tepelena might have helped Husein Gradaščević. Albanians were generally loyal to Ottoman rule after Skanderbeg's resistance ended. They accepted Islam more easily than their neighbors.

Semi-Independent Albanian Pashaliks

A period of semi-independence began in the mid-18th century. As Ottoman power weakened, the central government in Albania lost control. Local lords who wanted more freedom gained power. The most successful were three generations of pashas from the Bushati family. They ruled most of northern Albania from 1757 to 1831.

Another powerful figure was Ali Pasha Tepelena of Janina. He was a bandit who became a ruler. He controlled southern Albania and northern Greece from 1788 to 1822. These pashas created separate states within the Ottoman Empire. However, they were eventually overthrown by the sultan.

Modern Albania

National Rebirth

In the 1870s, the Ottoman Empire's efforts to stop its decline had failed. The idea of the "Turkish yoke" became strong in the minds of Balkan peoples. Their push for independence grew faster. The Albanians were the last Balkan people to seek separation from the Ottoman Empire. This was due to strong Islamic influence, internal divisions, and fear of losing their Albanian-speaking lands to new states like Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, and Greece.

With the rise of the Albanian National Awakening, Albanians gained a sense of nationhood. They fought against the Ottoman Empire and started a big revival of Albanian writing. Albanians living abroad in Bulgaria, Egypt, Italy, Romania, and the United States helped write and spread Albanian textbooks and writings.

The League of Prizren

In the mid-19th century, after the Albanian pashaliks fell, an Albanian National Awakening began. Many revolts against the Ottoman Empire were organized. These included revolts in the 1830s and 1840s. A key moment of this awakening was the League of Prizren. The League was formed at a meeting of 47 Ottoman leaders in Prizren on June 18, 1878.

The League's first goal was to keep the Ottoman Empire's lands in the Balkans whole. They promised to fight to defend "the wholeness of the territories of Albania." Early on, the League fought against Montenegro. They successfully took control of Plav and Gusinje after fierce battles. In August 1878, the Congress of Berlin ordered a group to decide the border between the Ottoman Empire and Montenegro. Finally, the Great Powers blocked Ulcinj by sea. They pressured the Ottoman authorities to control the Albanians. Albanian efforts helped them keep control of Epirus, but some lands were still given to Greece by 1881.

The League's founder, Abdyl Frashëri, pushed the League to demand freedom and fight the Ottomans. The sultan sent a large army to stop the League of Prizren. The League's leaders were arrested and sent away. Frashëri was imprisoned until 1885. A similar league was started in 1899 in Peja by Haxhi Zeka. This league ended in 1900 after fighting with Ottoman forces. Zeka was killed in 1902.

Gaining Independence

The First Balkan war in 1912 was sparked by Albanian uprisings from 1908 to 1910. These aimed to oppose the Young Turk policies. As the Ottoman Empire weakened in the Balkans, Serbia, Greece, and Bulgaria declared war. They took the remaining Ottoman land in Europe. Serbian forces occupied northern Albania, and Greek forces occupied the south. Only a small area around the southern city of Vlora remained.

The unsuccessful uprisings in 1910 and 1911, and the successful one in 1912, led to a declaration of independence. Ismail Qemali declared independence in Vlorë on November 28, 1912. On the same day, he waved the Albanian national flag from the balcony of the Assembly of Vlorë. This flag was made like Skanderbeg's principality flag from over 500 years before.

Albanian independence was recognized by the Conference of London on July 29, 1913. The Conference then set the borders between Albania and its neighbors. This left more than half of ethnic Albanians outside Albania. This population was divided among Montenegro, Serbia (including today's Kosovo and North Macedonia), and Greece.

At the same time, a Greek uprising in southern Albania led to the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus in 1914. This republic was short-lived as Albania collapsed with World War I. Greece held the area from 1914 to 1916. Italy took over most of Albania in 1917. The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 gave the area to Greece. However, it returned to Albanian control in November 1921 after Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War.

The Principality of Albania

The Great Powers supported Albania's independence. Aubrey Herbert, a British Member of Parliament, strongly supported the Albanian cause. He was offered the crown of Albania but declined. Instead, the offer went to William of Wied, a German prince. He accepted and became the ruler of the new Principality of Albania.

The Principality was established on February 21, 1914. Prince William of Wied was chosen as the ruler. He was called "Mbret" (King) in Albania, so he wouldn't seem less important than the King of Montenegro. During this time, Albanian religions gained independence. The Albanian Orthodox Church was recognized as independent in 1922. Albanian Muslims also declared their loyalty to Albania in 1923. They banned polygamy and allowed women to choose whether to wear a veil.

Security was handled by a Gendarmerie led by Dutch officers. William left Albania on September 3, 1914. This was due to a pan-Islamic revolt led by Essad Pasha Toptani and later Haxhi Qamili. William never gave up his claim to the throne.

World War I and Albania

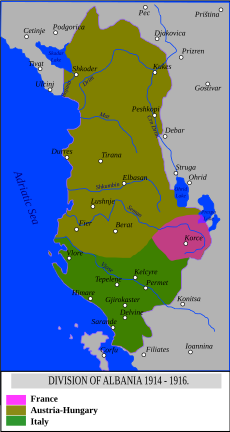

World War I stopped all government activities in Albania. The country was split into several regional governments. Political chaos took over after the war began. Albanians divided along religious and tribal lines after the prince left. Muslims wanted a Muslim prince and looked to Turkey. Other Albanians sought support from Italy. Many local leaders recognized no higher authority.

Prince William left Albania on September 3, 1914, because of the Peasant Revolt. He later joined the German army but never gave up his claim to the throne.

In late 1914, Greece occupied southern Albania, including Korçë and Gjirokastër. Italy occupied Vlorë. Serbia and Montenegro occupied parts of northern Albania. Then, Central Powers forces pushed back the Serbian army. Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian forces occupied about two-thirds of the country.

A secret agreement in April 1915, the Treaty of London, promised Italy Vlorë and a protectorate over Albania. Serbia and Montenegro were promised much of northern Albania. Greece was promised much of the southern half. The treaty left a tiny Albanian state, represented by Italy.

In September 1918, Allied forces broke through the Central Powers' lines. Austro-Hungarian forces began to leave Albania. On October 2, 1918, Durrës was shelled to prevent it from being used by retreating armies.

When the war ended on November 11, 1918, Italy's army held most of Albania. Serbia held many northern mountains. Greece occupied a small part of southern Albania. French forces occupied Korçë and Shkodër.

Plans to Divide Albania (1919–1920)

After World War I, Albania was still occupied by Serbian and Italian forces. Rebellions by people in northern and southern Albania pushed the Serbs and Italians back behind Albania's recognized borders.

Albania's political confusion continued after World War I. The country had no single recognized government. Albanians feared that Italy, Yugoslavia, and Greece would take away Albania's independence and divide the country. Italian forces controlled political activity in their occupied areas. The Serbs, who largely guided Yugoslavia's foreign policy, wanted to take northern Albania. The Greeks wanted to control southern Albania.

An Albanian delegation went to the Paris Peace Conference in December 1918. They defended Albanian interests, but Albania was not given official representation. The Albanian National Assembly wanted to keep Albania whole. They were willing to accept Italian protection or even an Italian prince as ruler, as long as Albania did not lose land. Serbian troops acted in Albanian border areas, and Albanian fighters operated in Serbia and Montenegro.

In January 1920, at the Paris Peace Conference, France, Britain, and Greece agreed to let Albania fall under Yugoslav, Italian, and Greek influence. This was a way to solve land disputes between Italy and Yugoslavia.

Members of a second Albanian National Assembly in January 1920 rejected this plan. They warned that Albanians would fight to defend their country's independence. The Lushnjë Assembly appointed a four-person group to rule the country. A two-house parliament was also created. In February 1920, the government moved to Tirana, which became Albania's capital.

One month later, in March 1920, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson stopped the Paris agreement. The United States supported Albania's independence. In December, the League of Nations recognized Albania's independence. However, the country's borders were still not fully settled until after the Vlora War.

Albania gained some stability after World War I, partly due to U.S. diplomatic help. However, the country lacked economic and social development. Its first years of independence were politically unstable. Albania became a point of tension between Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, both wanting to control it.

The Zogu Government

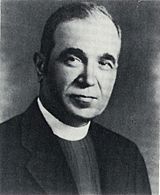

Albanian governments came and went quickly between the wars. From July to December 1921 alone, the prime minister changed five times. The Popular Party's leader, Xhafer Ypi, formed a government in December 1921. Fan S. Noli was foreign minister, and Ahmed Bey Zogu was internal affairs minister. But Noli resigned soon after Zogu used force to disarm people in the lowlands.

When enemies attacked Tirana in early 1922, Zogu stayed and fought them off with British support. He became prime minister later that year. Zogu's supporters formed the Government Party. Noli and other Western-minded leaders formed the Opposition Party of Democrats. This group included many of Zogu's personal enemies and people who disagreed with his ideas.

Many people opposed Zogu. Orthodox farmers in southern Albania disliked him because he supported Muslim landowners. Citizens of Shkodër felt ignored because their city was not the capital. Nationalists were unhappy because Zogu's government did not push Albania's claims to Kosovo.

Zogu's party won elections for a National Assembly in early 1924. However, Zogu soon stepped down. He gave the prime minister job to Shefqet Verlaci after a money scandal and an assassination attempt that wounded Zogu. The opposition left the assembly after a nationalist youth leader, Avni Rustemi, was killed outside the parliament building.

The June Revolution

Noli's supporters blamed Zogu's family for Rustemi's murder. After the walkout, unhappiness grew. In June 1924, a peasant-backed uprising took control of Tirana. The government fell easily with little violence. Only Zogu and his small group resisted. However, Noli's new government was unstable. It needed strong support and money from other countries.

Noli formed his own small government on June 16, 1924. It included people from all groups in the June rebellion. Noli believed Albania needed a "paternal" government and rejected new elections. On June 19, Noli's government proposed a twenty-point reform plan. This plan aimed for a country-wide revolution. Noli strongly criticized the previous government for ruining the budget and causing disorder.

The twenty-point plan included:

- Disarming everyone.

- Punishing those who caused conflict.

- Bringing back peace and order.

- Strengthening the state's power.

- Ending feudalism and bringing democracy.

- Making big changes in all government areas.

- Simplifying government work and making it cleaner.

- Protecting workers' rights.

- Improving villages and giving more power to local communities.

- Balancing the budget by saving money.

- Changing the tax system to help people.

- Improving conditions for farmers.

- Allowing foreign money into the country while protecting Albania's economy.

- Raising the country's standing in the world.

- Making the justice system truly independent.

- Changing old courts.

- Building new roads and improving communication.

- Organizing health care to fight diseases.

- Modernizing education to create capable citizens.

- Having friendly relations with all countries, especially neighbors.

Noli said that once things were normal, a national election would be held. He planned to rule by decree for ten to twelve months. He believed past elections did not show what Albanians truly wanted. Noli later said his party had majority support for land reforms, but not for carrying them out. The plan was to take land from wealthy owners and give it to farmers. Each family would get 4–6 hectares of land.

Noli's plan also included cutting government spending, strengthening local government, helping farmers, inviting foreign investment, and improving transportation, health, and education. Noli faced resistance from those who helped him remove Zogu. He also never got the foreign aid needed for his plans. Noli criticized the League of Nations for not helping with Albania's border threats.

Under Fan Noli, a special court sentenced Zogu and others to death in their absence. Their property was taken.

In Yugoslavia, Zogu gathered an army. Belgrade gave him weapons, Yugoslav soldiers, and Russian White Emigres. They planned an invasion. After Noli decided to have relations with the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia claimed Albania was becoming communist.

On December 13, 1924, Zogu's army, backed by Yugoslavia, entered Albania. By Christmas Eve, Zogu had taken back the capital. Noli and his government fled to Italy. Noli's government lasted only six months and a week.

The First Republic

After defeating Fan Noli's government, Ahmet Zogu called back the parliament. They needed to decide the future of the uncrowned principality of Albania. The parliament quickly adopted a new constitution. It declared Albania a republic and gave Zogu dictatorial powers. This allowed him to choose ministers, reject laws, and appoint many officials.

The new constitution created a parliamentary republic. It had a powerful president who was both head of state and government.

On January 31, Zogu was elected president for a seven-year term. Opposition parties and freedoms disappeared. People who opposed the government were killed. The press faced strict censorship. Zogu ruled Albania using four military governors who answered only to him. He appointed clan chiefs as army officers to protect his rule.

However, Zogu soon turned away from Belgrade. He looked instead to Benito Mussolini's Italy for support. Under Zogu, Albania joined an Italian alliance against Yugoslavia. This alliance included the Kingdom of Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria from 1924–1927. It fell apart after Britain and France intervened in 1927.

Zogu kept good relations with Mussolini's fascist government in Italy. He supported Italy's foreign policy. Zogu was the first and only Albanian to hold the title of president until 1991.

The Kingdom of Albania

In 1928, Zogu I got the Parliament to agree to dissolve itself. After that, Albania was declared a monarchy. Zogu I became the first Prime Minister, then President, and finally the King of Albania. Other countries quickly recognized him. The new constitution got rid of the Albanian Senate. It created a single-house parliament. But King Zog kept the dictatorial powers he had as president. Zogu I remained conservative but started some reforms. For example, he stopped the custom of adding one's region to one's name. He also gave land to international groups to build schools and hospitals.

Soon after becoming king, Zog ended his engagement to Shefqet Verlaci's daughter. Verlaci then stopped supporting the king and started plotting against him. Zog had made many enemies over the years. The Albanian tradition of blood vengeance meant they would try to kill him. Zog surrounded himself with guards and rarely appeared in public. The king's loyalists disarmed all Albanian tribes except his own and their allies. Still, during a visit to Vienna in 1931, Zog and his bodyguards fought a gun battle with assassins outside the Opera House.

Zog was aware of the growing unhappiness with Italy's control over Albania. The Albanian army, though small, drained the country's money. Italy's control over army training also angered public opinion. To balance this, Zog kept British officers in the Gendarmerie, despite Italian pressure. In 1931, Zog openly stood up to the Italians. He refused to renew the 1926 First Treaty of Tirana.

Financial Problems

In 1932 and 1933, Albania could not pay the interest on its loans from Italy. Rome then put more pressure on Albania. They demanded that Tirana appoint Italians to lead the Gendarmerie. They also wanted Albania to join a customs union with Italy. They asked for control of Albania's sugar, telegraph, and electricity companies. Italy also wanted Italian to be taught in all Albanian schools and for Italian settlers to be allowed into the country. Zog refused.

Instead, he ordered the national budget to be cut by 30 percent. He fired the Italian military advisers. He also took over Italian-run Roman Catholic schools in northern Albania. In 1934, Albania signed trade agreements with Yugoslavia and Greece. Mussolini then stopped all payments to Tirana. Italy tried to scare Albanians by sending warships to Albania. But the Albanians only allowed the forces to land if they were unarmed. Mussolini then tried to buy off the Albanians. In 1935, he gave the Albanian government 3 million gold francs as a gift.

Zog's success in stopping two local rebellions convinced Mussolini that they needed a new agreement with the Albanian king. A government of young men led by Mehdi Frasheri got Italy to fulfill its financial promises. Italy also gave new loans for port improvements at Durrës and other projects. These loans kept the Albanian government going. Soon, Italians started taking jobs in Albania's government. Italian settlers were allowed into the country. Mussolini's forces overthrew King Zog when Italy invaded Albania in 1939.

World War II

Starting in 1928, and especially during the Great Depression, King Zog's government brought order to the country. However, it also increased Italian influence. Despite some strong resistance, especially at Durrës, Italy invaded Albania on April 7, 1939. They took control of the country. The Italian Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini declared Italy's King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy as King of Albania. Albania became one of the first countries occupied by the Axis Powers in World War II.

As Hitler attacked other European countries, Mussolini decided to occupy Albania. He wanted to compete with Hitler's land gains. Mussolini and the Italian Fascists saw Albania as historically part of the Roman Empire. The occupation was meant to fulfill Mussolini's dream of creating an Italian Empire. During the Italian occupation, Albanians were forced to adopt Italian culture. The use of the Albanian language was discouraged in schools, and Italian was promoted. Italian people were also encouraged to settle in Albania.

In October 1940, Mussolini used his Albanian base to attack Greece. This led to the defeat of Italian forces. Greece occupied Southern Albania, which Greeks saw as the liberation of Northern Epirus. While preparing for the invasion of Russia, Hitler decided to attack Greece in December 1940. He wanted to prevent a British attack on his southern side.

Italian Influence

The Italian invasion of Albania in April 1939 was the result of centuries of Italian interest. It also followed twenty years of direct, though not always successful, economic and political involvement in Albania. This was mainly under Benito Mussolini. The Straits of Otranto, which connect Albania and southern Italy, have always been a bridge. They offered escape, cultural exchange, and an easy invasion route. Before World War I, Italy and Austria-Hungary helped create an independent Albanian state. When the war started, Italy took the chance to occupy southern Albania. They wanted to prevent it from being taken by the Austro-Hungarians. This success did not last long. After-war problems in Italy, Albanian resistance, and pressure from U.S. President Woodrow Wilson forced Italy to leave in 1920.

When Mussolini came to power in Italy, he renewed his interest in Albania. Italy began to control Albania's economy in 1925. Albania agreed to let Italy use its mineral resources. This was followed by the First Treaty of Tirana in 1926 and the Second Treaty of Tirana in 1927. These treaties formed a defensive alliance between Italy and Albania. The Albanian government and economy received money from Italian loans. The Albanian army was trained by Italian military instructors. Italian settlers were encouraged to move to Albania. Despite strong Italian influence, Zog refused to completely give in to Italian pressure. In 1931, he openly stood up to the Italians. He refused to renew the 1926 Treaty of Tirana. After Albania signed trade agreements with Yugoslavia and Greece in 1934, Mussolini tried to scare the Albanians. He sent a fleet of warships to Albania, but it failed.

As Nazi Germany took over Austria and Czechoslovakia, Italy felt it was becoming a less important Axis power. The upcoming birth of an Albanian royal child also threatened to give Zog a lasting royal family. After Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia in March 1939 without telling Mussolini, the Italian dictator decided to annex Albania. Italy's King Victor Emmanuel III criticized the plan as too risky. However, Rome gave Tirana an ultimatum on March 25, 1939. It demanded that Albania accept Italy's occupation. Zog refused to accept money in exchange for a full Italian takeover and colonization of Albania.

Italian Invasion

On April 7, Mussolini's troops invaded Albania. General Alfredo Guzzoni led the operation. The invasion force was split into three groups, landing one after another. The first group was the most important. It was divided into four columns, each targeting a harbor and an inland area. Despite some strong resistance from Albanian patriots, especially at Durrës, the Italians quickly defeated the Albanians. Durrës was captured on April 7, Tirana the next day. Shkodër and Gjirokastër fell on April 9, and almost the entire country by April 10.

King Zog, his wife Queen Geraldine Apponyi, and their baby son Leka did not want to be Italian puppets. They fled to Greece and eventually to London. On April 12, the Albanian parliament voted to remove Zog. They decided to unite Albania with Italy "in personal union." They offered the Albanian crown to Victor Emmanuel III.

The parliament elected Albania's largest landowner, Shefqet Bej Verlaci, as Prime Minister. Verlaci also served as head of state for five days. Then, Victor Emmanuel III formally accepted the Albanian crown in Rome. Victor Emmanuel III appointed Francesco Jacomoni di San Savino, a former ambassador to Albania, to represent him in Albania. He was called "Lieutenant-General of the King," which was like a viceroy.

Albania Under Italy

While Victor Emmanuel was king, Shefqet Bej Verlaci served as Prime Minister. He managed the daily activities of the new Italian protectorate. On December 3, 1941, Mustafa Merlika Kruja replaced Shefqet Bej Verlaci as Prime Minister and Head of State.

From the start, Albania's foreign affairs, customs, and natural resources were directly controlled by Italy. The puppet Albanian Fascist Party became the ruling party. The Fascists allowed Italian citizens to settle in Albania and own land. Their goal was to gradually turn Albania into Italian territory.

In October 1940, during the Greco-Italian War, Albania was used as a base. Italian dictator Benito Mussolini launched an unsuccessful invasion of Greece from there. Mussolini planned to invade Greece and other countries like Yugoslavia. He wanted Italy to control most of the Mediterranean Sea coastline. This was part of the Fascist goal of creating Mare Nostrum ("Our Sea").

But soon after the Italian invasion, the Greeks fought back. A large part of Albania came under Greek control, including Gjirokastër and Korçë. In April 1941, after Greece surrendered to German forces, the Greek territorial gains in southern Albania returned to Italian command. Large areas of Greece also came under Italian command after the successful German invasion of Greece.

After Yugoslavia and Greece fell in April 1941, the Italian Fascists added more land to the Kingdom of Albania. This included most Albanian-inhabited areas that had been given to Yugoslavia. Albanian fascists claimed in May 1941 that almost all Albanian-populated areas were united with Albania. Even parts of northern Greece (Chameria) were managed by Albanians. This was also a result of the borders Italy and Germany agreed upon when dividing their areas of influence. Some small areas with Albanian majorities remained outside the new borders. Contact between the two parts was almost impossible. The Albanian population under Bulgarian rule was heavily oppressed.

Albania Under Germany

After the Italian Army surrendered in September 1943, Albania was occupied by the Germans.

When Mussolini's government fell and the Allies invaded Italy, Germany occupied Albania in September 1943. German paratroopers landed in Tirana before Albanian fighters could take the capital. The German Army soon pushed the fighters into the hills and to the south. The Nazi German government then announced it would recognize an independent, neutral Albania. They began to organize a new government, police, and armed forces.

The Germans did not control Albania's government too strictly. Instead, they tried to gain public support by backing causes popular with Albanians. This included the annexation of Kosovo. Many Balli Kombëtar units worked with the Germans against the communists. Several Balli Kombëtar leaders held positions in the German-backed government. Albanian collaborators, especially the Skanderbeg SS Division, also expelled and killed Serbs in Kosovo.

In December 1943, a third resistance group formed in northern Albania. This was an anti-communist, anti-German royalist group called Legaliteti. Led by Abaz Kupi, it mostly consisted of Geg fighters. They were supplied mainly by the Allies, who stopped supporting them after the communists gave up Albania's claims on Kosovo.

The capital, Tirana, was freed by the partisans on November 17, 1944, after a 20-day battle. The communist partisans fully liberated Albania from German occupation on November 29, 1944. They chased the German army into Bosnia, working with Yugoslav communist forces.

The Albanian partisans also freed Kosovo, parts of Montenegro, and southern Bosnia and Herzegovina. By November 1944, they had driven out the Germans. Albania and Yugoslavia were the only European nations to do this without Allied help. Enver Hoxha became the country's leader as Secretary General of the Albanian Communist Party.

After taking power, the Albanian communists started a huge campaign of terror. They shot intellectuals and arrested thousands of innocent people. Some died from torture.

Albania was one of the only European countries occupied by the Axis powers that ended World War II with more Jewish people than before the war. About 1,200 Jewish residents and refugees were hidden by Albanian families during World War II.

Albanian Resistance in World War II

The National Liberation War of the Albanian people began with the Italian invasion on April 7, 1939. It ended on November 28, 1944. During this anti-fascist war, Albanians fought against Italy and Germany, who occupied the country. From 1939 to 1941, nationalist groups led the resistance. Later, the Communist Party took over.

Communist Resistance

In October 1941, small Albanian communist groups formed the Albanian Communist Party in Tirana. It had 130 members and was led by Hoxha. The Albanian communists supported the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. They did not join the anti-fascist fight until Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. At first, the party was not very popular. But in mid-1942, party leaders gained support. They called on young people to fight for their country's freedom from Fascist Italy.

This message brought many young people eager for freedom to join. In September 1942, the party created a popular front group called the National Liberation Movement (NLM). This group included several anti-communist resistance groups. During the war, the NLM's communist-led fighters, the National Liberation Army, ignored warnings from Italian occupiers about revenge for attacks.

The communists turned the "war of liberation" into a civil war. This happened especially after the discovery of the Dalmazzo-Kelcyra protocol, signed by the Balli Kombëtar. To organize partisan resistance, they held a conference in Pezë on September 16, 1942. There, the Albanian National Liberation Front was set up. This Front included nationalist groups but was controlled by communist partisans.

In December 1942, more Albanian nationalist groups formed. Albanians fought against the Italians. During Nazi German occupation, Balli Kombëtar allied with the Germans. They clashed with Albanian communists, who continued fighting both Germans and Balli Kombëtar.

Nationalist Resistance

A nationalist resistance against the Italian occupiers appeared in November 1942. Ali Këlcyra and Midhat Frashëri formed the Western-oriented Balli Kombëtar (National Front). Balli Kombëtar attracted supporters from both large landowners and farmers. It opposed King Zog's return. It called for a republic and some economic and social reforms. However, Balli Kombëtar's leaders acted carefully. They feared that the occupiers would punish them or take their lands.

Communist Revolution in Albania (1944)

The communist partisans regrouped and took control of southern Albania by January 1944. In May, they held a meeting of the National Liberation Front (NLF) in Përmet. They chose an Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation to act as Albania's government. Hoxha became the chairman of this council and the supreme commander of the National Liberation Army.

The communist partisans defeated the last Balli Kombëtar forces in southern Albania by mid-summer 1944. They faced little resistance from Balli Kombëtar and Legaliteti when they entered central and northern Albania by late July. The British military advised the remaining nationalists not to fight the communists. The Allies evacuated Kupi to Italy. Before the end of November, the main German troops left Tirana. The communists took control of the capital after fighting the remaining German army. A temporary government formed by the communists in Berat in October ruled Albania, with Enver Hoxha as prime minister.

War Consequences

The NLF's strong ties with Yugoslavia's communists meant that Belgrade would play a key role in Albania after the war. The Allies never recognized an Albanian government in exile or King Zog. They also never discussed Albania or its borders at major wartime meetings.

There are no exact numbers for Albania's wartime losses. However, the United Nations reported about 30,000 Albanian war deaths. Also, 200 villages were destroyed, 18,000 houses ruined, and about 100,000 people became homeless. Albanian official numbers claim higher losses. Additionally, thousands of Chams (Albanians living in Northern Greece) were forced out of Greece. This was because they were accused of working with the Nazis.

The Second Republic

Communism in Albania

After World War II, communists quickly moved to control all political enemies in Albania. They broke the power of landowners and the small middle class. They also isolated Albania from Western countries to create the People's Republic of Albania. By 1945, the communists had removed, disgraced, or forced into exile most of the country's pre-war leaders. The Internal Affairs Minister, Koçi Xoxe, oversaw the trials and executions of thousands of opposition politicians and clan chiefs. They were called "war criminals."

Thousands of their family members were imprisoned for years. Later, they were exiled for decades to poor state farms built on reclaimed marshlands. The communists' control also shifted political power in Albania. It moved from the northern Ghegs to the southern Tosks. Most communist leaders were middle-class Tosks, Vlachs, and Orthodox Christians. The party got most of its members from Tosk areas. The Ghegs, who had a long history of opposing authority, did not trust the new Albanian rulers or their foreign Marxist ideas.

In December 1945, Albanians elected a new People's Assembly. However, only candidates from the Democratic Front were on the ballot. The communists used propaganda and fear to silence the opposition. Official results showed that 92% of voters participated, and 93% chose the Democratic Front. The assembly met in January 1946. It ended the monarchy and turned Albania into a "people's republic."

The new leaders faced many problems in Albania: widespread poverty, high illiteracy, gjakmarrje ("blood feuds"), diseases, and women being treated unfairly. To fix these, the Communists started a plan for fast modernization. The first step was a quick and strict agrarian reform. This broke up large estates and gave land to farmers. This destroyed the powerful bey class. The government also decided to nationalize industries, banks, and all foreign properties. Soon after the land reform, the Albanian government began to collectivise agriculture. This process continued until 1967. In rural areas, the communist government stopped the old blood feuds and the male-dominated family structure. This destroyed the semi-feudal Bajraktars class. The traditional role of women, who were confined to home and farm, changed greatly. They gained legal equality with men and became active in all parts of society.

Enver Hoxha and Mehmet Shehu became the main communist leaders in Albania. They focused on keeping their power by killing political rivals. They also worked to keep Albania independent and reshape the country based on Stalinism. This helped them stay in power and develop the economy. Political killings were common. Between 5,000 and 25,000 people were killed under the communist rule. According to one Albanian group, 6,000 people were executed from 1945 to 1991.

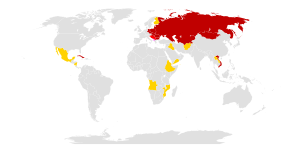

Albania became an ally of the Soviet Union. But this ended after 1956 due to de-Stalinization, causing the Soviet-Albanian split. A strong alliance with China followed, bringing billions of dollars in aid. This aid was cut after 1974, leading to the Sino-Albanian split. China stopped aid in 1978 when Albania criticized its policies after Mao Zedong's death. Many officials were removed from power in the 1970s.

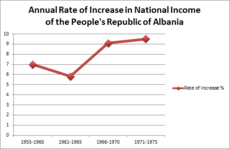

During the communist period, Albania's economy grew quickly. For the first time, Albania produced most of its own goods. Some could even compete in foreign markets. From 1960 to 1970, Albania's national income grew much faster than the world and European averages. Also, because of the state-controlled economy, Albania was the only country in the world that had no taxes on its people.

Enver Hoxha, who ruled Albania for four decades, died on April 11, 1985. Soon after his death, people in Albania started asking for change. The government began to seek closer ties with the West to improve the economy.

Eventually, the new leader Ramiz Alia introduced some freedoms. He allowed people to travel abroad in 1990. The new government tried to improve relations with other countries. The elections in March 1991 kept the former Communists in power. But a general strike and city protests led to a coalition government that included non-Communists.

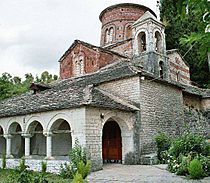

In 1967, the government started a strong campaign to stop religious practices. They claimed religion had divided the Albanian nation and kept it backward. Students went through the country, forcing Albanians to stop practicing their faith. Despite complaints, all churches, mosques, and other religious places were closed or turned into warehouses or workshops by the end of the year. A special law ended the official status of the country's main religious groups.

Albania and Yugoslavia

Until Yugoslavia was kicked out of the Cominform in 1948, Albania acted like a Yugoslav satellite. The President of Yugoslavia, Josip Broz Tito, wanted to use his influence over the Albanian party to make Albania part of Yugoslavia. After Germany left Kosovo in late 1944, Yugoslavia's communist fighters took over the province. They carried out revenge killings against Albanians. Before World War II, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia had supported giving Kosovo to Albania. But Yugoslavia's post-war communist government insisted on keeping the country's pre-war borders.

Albania's communists agreed to give Kosovo back to Yugoslavia after the war. This happened under pressure from the Yugoslavs. In January 1945, the two governments signed a treaty. It made Kosovo an autonomous province within Yugoslavia. Soon after, Yugoslavia was the first country to recognize Albania's temporary government.

However, relations between Albania and Yugoslavia worsened. Albanians complained that Yugoslavs paid too little for Albanian raw materials. They also felt Yugoslavia was taking advantage of Albania through joint companies. Albanians wanted money to develop light industries and an oil refinery. Yugoslavs wanted Albanians to focus on farming and getting raw materials. The head of Albania's Economic Planning Commission, Nako Spiru, became the main critic of Yugoslavia's economic control. Tito did not trust Hoxha and other Albanian party intellectuals. He tried to remove them through Xoxe and his loyalists.

In 1947, Yugoslavia's leaders started a full attack against anti-Yugoslav Albanian communists, including Hoxha and Spiru. In May, Tirana announced the arrest and conviction of nine members of the People's Assembly. All were known for opposing Yugoslavia. They were charged with anti-state activities. A month later, Yugoslavia's Communist Party accused Hoxha of having "independent" policies and turning Albanians against Yugoslavia.

Albania and the Soviet Union

Albania became dependent on Soviet aid after its break with Yugoslavia in 1948. In February 1949, Albania joined the communist bloc's organization for economic planning, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance. Tirana soon made trade agreements with Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and the Soviet Union. Soviet and central European technical experts moved to Albania. The Soviet Union also sent military advisers and built a submarine base on Sazan Island.

After the Soviet-Yugoslav split, Albania and Bulgaria were the only countries the Soviet Union could use to send war materials to communists fighting in Greece. However, Albania's strategic value to the Soviet Union decreased as nuclear weapons developed.

Albania's rulers copied parts of the Stalinist economic system to honor Stalin. In 1949, Albania adopted the Soviet financial system. State companies paid profits to the government and kept only a small part for investments. In 1951, the Albanian government launched its first five-year plan. This plan focused on using the country's oil, chromite, copper, and coal. It also aimed to increase electricity production and farming. The government started a fast industrialization program after the APL's Second Party Congress. They also began forced collectivization of farmland in 1955. At that time, private farms produced about 87% of Albania's farm output. But by 1960, the same percentage came from collective or state farms.

Stalin died in March 1953. Hoxha and Shehu did not go to his funeral in Moscow. They feared his death might encourage rivals in the Albanian party. The Soviet Union's move to improve relations with the hated Yugoslavs angered the two Albanian leaders. Tirana soon faced pressure from Moscow to adopt the new Soviet model of collective leadership. In July 1953, Hoxha gave his foreign affairs and defense jobs to loyal followers. But he kept the top party job and the prime minister role until 1954, when Shehu became prime minister. The Soviet Union tried to boost Albanian leaders' morale. They raised diplomatic relations between the two countries to the ambassador level.

Despite some early excitement, Hoxha and Shehu did not trust Nikita Khrushchev's ideas of "peaceful coexistence." They feared Yugoslavia might try to control Albania again. Hoxha and Shehu were also worried that Moscow might prefer less strict rulers in Albania. Tirana and Belgrade restarted diplomatic relations in December 1953. But Hoxha refused Khrushchev's requests to honor the pro-Yugoslav Xoxe after his death. The Albanian leaders instead tightened their control over their country and continued their propaganda war with the Yugoslavs.

Albania and China

The People's Republic of Albania played a much bigger role in the Sino-Soviet split than its size suggested. In 1958, Albania supported the People's Republic of China. They disagreed with Moscow on issues like peaceful coexistence, de-Stalinization, and Yugoslavia's different path to socialism. The Soviet Union, central European countries, and China all offered Albania large amounts of aid. Soviet leaders also promised to build a large Palace of Culture in Tirana. This was meant to show the Soviet people's "love and friendship" for Albanians.

Despite these gestures, Tirana was unhappy with Moscow's economic policy toward Albania. Hoxha and Shehu seemed to decide in May or June 1960 that China would support Albania. They openly sided with China when strong arguments broke out between China and the Soviet Union. Ramiz Alia, who was a Politburo candidate and Hoxha's adviser on ideas, played a big role in these arguments.

Hoxha and Shehu continued to criticize the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia at the APL's Fourth Party Congress in February 1961. During the congress, the Albanian government announced its Third Five-Year Plan (1961-65). This plan put 54% of all investment into industry. This rejected Khrushchev's wish to make Albania mainly an agricultural producer. Moscow responded by canceling aid and loans for Albania. But the Chinese again came to help.

By 1970, Albanian-Chinese relations had slowed down. When China started to open up in the early 1970s, Mao Zedong and other Chinese leaders rethought their commitment to tiny Albania. This started the Sino-Albanian split. In response, Tirana began to make more contacts with the outside world. Albania started trade talks with France, Italy, and newly independent Asian and African states. In 1971, it normalized relations with Yugoslavia and Greece. Albania's leaders disliked China's contacts with the United States in the early 1970s. Their press and radio ignored President Richard Nixon's trip to Beijing in 1972.

The Third Republic

As Hoxha's health got worse, the first secretary of the People's Socialist Republic of Albania planned for a smooth change in leadership. In 1976, the People's Parliament adopted its second communist Constitution since the war. The constitution promised freedom of speech, press, and organization. But these rights were less important than a person's duties to society. The constitution also made it law that Albania would be self-sufficient. It banned the government from seeking money or loans from capitalist or "revisionist" communist countries. The constitution also proudly stated that religious belief had been ended in Albania.

In 1980, Hoxha chose Ramiz Alia to be his successor. He passed over his long-time friend, Mehmet Shehu. Hoxha first tried to convince Shehu to step down. When that failed, Hoxha arranged for all Politburo members to criticize Shehu. This was because Shehu allowed his son to get engaged to the daughter of a former wealthy family. Hoxha removed Shehu's family members and his supporters from the police and military. In November 1982, Hoxha announced that Shehu had been a foreign spy. He claimed Shehu worked for the United States, British, Soviet, and Yugoslav intelligence agencies. Hoxha said Shehu planned to kill him. "He was buried like a dog," the dictator wrote in his book. Hoxha went into semi-retirement in early 1983. Alia took over running Albania. Alia traveled widely, representing Hoxha at events and giving speeches about new policies. He became president and legal secretary of the APL two days later. He became a dominant figure in Albanian media, and his slogans appeared across the country.

The Fourth Republic

Transition to Democracy

In 1985, Ramiz Alia became the first President of Albania. Alia tried to follow Enver Hoxha's path. But changes had already begun. The collapse of communism across Europe led to big changes in Albanian society. Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union introduced new rules like glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring). Alia took similar steps. He signed the Helsinki Agreement and allowed more political freedom under pressure from students and workers.

Afterward, the first multi-party elections since the communists took power happened. The Socialist Party led by Ramiz Alia won the 1991 elections. However, it was clear that change would not stop. On April 29, 1991, an interim law was passed. On November 28, 1998, Albanians approved a new constitution. This set up a democratic system based on the rule of law. It also guaranteed fundamental human rights.

The Communists kept support and government control in the first elections under the interim law. But they fell two months later during a general strike. A "national salvation" committee took over but also collapsed in six months. On March 22, 1992, the Communists were defeated by the Democratic Party. This happened after the 1992 parliamentary elections. The change from a socialist state to a parliamentary system had many challenges. The Democratic Party had to make the reforms it promised. But they were either too slow or did not solve the problems. People were disappointed when their hopes for quick wealth did not come true.

Becoming More Democratic

The Democratic Party took control after winning the second multi-party elections. They removed the Communist Party. Afterward, Sali Berisha became the second President. Today, Berisha is the longest-serving president and the only one elected to a second term. In 1995, Albania became the 35th member of the Council of Europe. It also asked to join North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Many Albanians have continued to move to Western European countries, especially to Greece and Italy, but also to the United States. Programs for economic and democratic reforms were put in place. But Albania's lack of experience with capitalism led to many pyramid schemes. These were not banned due to government corruption. Chaos in late 1996 and early 1997 worried the world. It led to international help.

In early spring 1997, Italy led a multinational military and humanitarian mission (Operation Alba). This was approved by the United Nations Security Council. It aimed to help stabilize the country. Berisha's government collapsed in 1997. This happened after more pyramid schemes failed and widespread corruption. This caused chaos and rebellion across the country. The government tried to stop the rebellion with military force, but it failed. This was due to long-term problems in the Military of Albania.

A few months later, after the 1997 parliamentary elections, the Democratic Party lost to the Socialist Party. The Socialists won 25 out of 156 seats. Sali Berisha resigned. The Socialists elected Rexhep Meidani as President. The Socialist leader Fatos Nano became Prime Minister. He held this post until October 1998, when he resigned. This was due to the tense situation after the killing of Azem Hajdari, a leader of the Democratic Party. Pandeli Majko then became Prime Minister until November 1999. He was replaced by Ilir Meta. The Parliament adopted the current Constitution on November 29, 1998. Albania approved its constitution through a public vote in November 1998. The opposition boycotted this vote. The local elections in October 2000 showed the Democrats lost control of local governments. It was a victory for the Socialists.

In 2001, Albania made progress toward democratic reform and the rule of law. However, serious problems in the election laws still needed fixing, as seen in the elections. International observers said the elections were acceptable. But the Union for Victory Coalition, the second-largest group, disagreed with the results. They boycotted parliament until January 31, 2002. In June 2005, the democratic coalition formed a government with Sali Berisha. His return to power in the July 3, 2005, elections ended eight years of Socialist Party rule. After Alfred Moisiu, Bamir Topi was elected President of Albania in 2006 until 2010. Despite the political situation, Albania's economy grew by an estimated 5% in 2007. The Albanian lek strengthened from 143 lekë to the US dollar in 2000 to 92 lekë in 2007.

Present Day Albania

On June 23, 2013, the seventh parliamentary elections took place. Edi Rama of the Socialist Party won. During his time as Prime Minister, Albania has made many reforms. These focus on modernizing the economy and making state institutions more democratic. This includes the justice system and law enforcement. Also, unemployment has steadily dropped to the 4th lowest rate in the Balkans.

After the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, Albania began to build closer ties with Western Europe. At the 2008 Bucharest summit, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) invited Albania to join. In April 2014, Albania became a full member of NATO. Albania was among the first southeastern European countries to join the Partnership for Peace program. Albania applied to join the European Union. It became an official candidate in June 2014.

In 2017, the eighth parliamentary elections happened at the same time as the presidential elections. The presidential elections were held in April 2017. In the fourth round, the current Chairman and then-Prime Minister, Ilir Meta, was elected as the eighth President of Albania with 87 votes. The parliamentary elections on June 25, 2017, were won by the Socialist Party led by Edi Rama. They received 48.33% of the votes. Lulzim Basha, the Democratic Party candidate, came second with 28.81% of the votes.

In the April 2021 parliamentary election, the ruling Socialist Party, led by Prime Minister Edi Rama, won its third straight victory. They got almost half of the votes and enough seats to govern alone. In February 2022, Albania's Constitutional Court overturned parliament's attempt to remove President Ilir Meta. In June 2022, the Albanian parliament elected Bajram Begaj, the Socialist Party's candidate, as the new President of Albania. On July 24, 2022, Bajram Begaj was sworn in as Albania's ninth president. On July 19, 2022, Albania started talks to join the European Union. Also, on December 6, the first EU-Western Balkans Summit was held in Tirana.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Albania para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Albania para niños