History of New Brunswick facts for kids

The history of New Brunswick tells the story of this Canadian province from ancient times to today. Thousands of years ago, the first people, called Paleo-Indians, arrived. Before Europeans came, different First Nations groups lived here for a very long time. The most well-known were the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, and Passamaquoddy peoples.

French explorers first visited New Brunswick in the 1500s. They started settling the area in the 1600s as part of a colony called Acadia. In the early 1700s, many Acadians moved to this area after France gave up its claim to Nova Scotia in 1713. Later, during the Seven Years' War, many Acadians were moved away by the British. After this war, France also gave up its remaining lands in North America to the British, including what is now New Brunswick.

For about 20 years, New Brunswick was part of the colony of Nova Scotia. But in 1784, the western parts were separated to form the new colony of New Brunswick. This happened partly because many Loyalists (people who stayed loyal to Britain) settled in British North America after the American Revolutionary War. In the 1800s, New Brunswick saw many new settlers, including Acadians who had returned, people from Wales, and a large number of Irish immigrants.

In the 1860s, talks about uniting the Maritime provinces led to Canadian Confederation. New Brunswick joined Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada (which became Ontario and Quebec) to form a new country in July 1867. New Brunswick's economy faced tough times in the late 1800s but started to grow again in the early 1900s. In the 1960s, the government started an equal opportunity program to help French-speaking people get fair services. By 1969, New Brunswick became officially bilingual (English and French) under the New Brunswick Official Languages Act.

Contents

Early History of New Brunswick

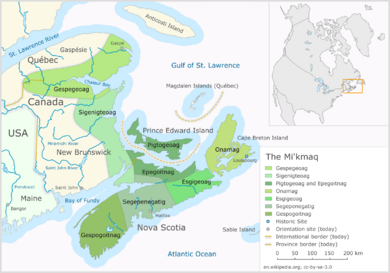

The First Nations in New Brunswick include the Mi'kmaq, Maliseet/Wəlastəkwiyik, and Passamaquoddy. The Mi'kmaq mainly lived in the eastern part of the province. The Maliseets lived along the St. John River. The Passamaquoddy lived in the southwest, near Passamaquoddy Bay. People have lived in New Brunswick for at least 13,000 years.

The Maliseet People

The "Maliseet" people are also known as Wəlastəkwiyik. In French, they are called Malécites or Étchemins. They are a First Nations group who live in the St. John River valley. Their land stretched along the St. John River, crossing the border between New Brunswick and Quebec in Canada, and Maine in the United States.

Wəlastəkwiyik is what the people of the St. John River call themselves. Their language is Wəlastəkwey. The Mi'kmaq people called them "Maliseet" because their language sounded like a slower version of Mi'kmaq. The Wəlastəkwiyik people named themselves after the St. John River, which they called the Wəlastəkw. This means "good river" because of its gentle waves. So, Wəlastəkwiyik means "People of the Good River."

Before Europeans arrived, the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy peoples moved with the seasons. In spring, they went downriver to fish and plant crops like corn, beans, and squash. They also held yearly gatherings. In summer, they moved to the saltwater areas to gather seafood and berries. In early autumn, they went upstream to harvest their crops and get ready for winter. After the harvest, small family groups spread out to their hunting grounds to hunt and trap during the winter.

The Passamaquoddy People

The Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati or Pestomuhkati in their own language) are a First Nations group. They live in northeastern North America, in Maine and New Brunswick.

Like the Maliseet, the Passamaquoddy moved around. They lived in the woods and mountains along the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine. They also lived along the St. Croix River. In winter, they spread out to hunt inland. In summer, they gathered closer to the coast and islands. They farmed corn, beans, and squash, and gathered seafood like porpoise.

The name Passamaquoddy comes from their own word, Peskotomuhkatiyik. It means "pollock-spearer," showing how important this fish was to them. Like the Maliseet, they used spears to fish instead of hooks.

Since the 1500s, European settlers often moved the Passamaquoddy off their land. In the United States, they were eventually given two reservations in Maine. The Passamaquoddy also live in Charlotte County, New Brunswick. They have recently gained official status as a First Nation in Canada. They are now working to get back lands in the county, including Ktaqamkuk, which is their name for St. Andrews, New Brunswick. This was once their main village.

The Mi'kmaq People

The Mi'kmaq (also spelled Micmac in older English texts) are a First Nations group. They are native to Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, the Gaspé peninsula in Quebec, and the eastern half of New Brunswick. Míkmaw is the name of their language.

In 1616, a French priest named Father Biard thought there were more than 3,000 Mi'kmaq people. However, he noted that many had died from European diseases, like smallpox, in the century before.

Wabanaki Confederacy

During the colonial wars, the Mi'kmaq were allies with four Abenaki nations. These were the Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet. Together, they formed the Wabanaki Confederacy. When the French first arrived in the late 1500s, the Mi'kmaq were expanding their territory westward. They moved from their Maritime base along the Gaspé Peninsula and St. Lawrence River. This is why the Mi'kmaq name for this peninsula is Gespeg, meaning "last-acquired."

The Mi'kmaq were okay with some French settlements among them. But as France lost control of Acadia in the 1700s, the Mi'kmaq soon faced many British settlers. These British settlers often took land without paying and moved the French away. Later, the Mi'kmaq also settled in Newfoundland after the unrelated Beothuk tribe died out.

Norse Explorers

Many experts believe that Vikings explored the coasts of Atlantic Canada, including New Brunswick. This happened during their time in Vinland, which might have been at L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, around the year 1000. Wild walnut (butternut) shells found at L'Anse aux Meadows suggest that the Vikings did explore further along the Atlantic Coast. Butternut trees do not grow in Newfoundland now. However, studies suggest that due to climate changes, butternuts might have grown there around 1000-1001 AD.

French Colonial Times

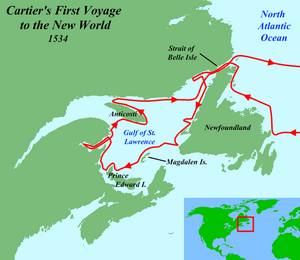

The first time Europeans explored what is now New Brunswick was in 1534. French explorer Jacques Cartier discovered and named the Baie des Chaleurs. This bay is between northern New Brunswick and the Gaspé peninsula of Quebec.

The next French visit was in 1604. A group led by Pierre Dugua (Sieur de Monts) and Samuel de Champlain sailed into Passamaquoddy Bay. They set up a winter camp on St. Croix Island at the mouth of the St. Croix River. By the end of winter, 36 out of 87 people died from scurvy. The next year, the colony moved across the Bay of Fundy to Port-Royal in what is now Nova Scotia. Over time, other French settlements and land grants (called seigneuries) were started. These were along the Saint John River and near today's Saint John. This included Fort La Tour and Fort Anne. There were also villages in the Memramcook and Petitcodiac river valleys, and the Beaubassin area. Another settlement was St. Pierre, founded by Nicolas Denys, where Bathurst is today.

At that time, all of New Brunswick (and Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and parts of Maine) was part of the French colony of Acadia. The French had good relationships with the First Nations. This was mainly because French settlers stayed in small farming communities along the coast. They left the inland areas to the Indigenous peoples. This good relationship was also helped by a strong fur trading business.

The British (English and Scottish) also claimed the region in 1621. Sir William Alexander was given all of present-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and part of Maine by King James VI & I. This whole area was to be called "Nova Scotia," which means "New Scotland" in Latin. Of course, the French did not like the British claims. However, France slowly lost control of Acadia in a series of wars during the 1700s.

17th Century Conflicts

Acadian Civil War

Acadia faced a conflict that some historians call the Acadian Civil War. This war was between Port Royal, where Governor of Acadia Charles de Menou d'Aulnay de Charnisay was based, and present-day Saint John, New Brunswick, where Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour was based.

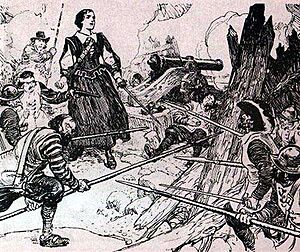

There were four main battles in this war. La Tour attacked d'Aulnay at Port Royal in 1640. In response, d'Aulnay sailed from Port Royal and blocked La Tour's fort at Saint John for five months. La Tour eventually won this fight in 1643. La Tour attacked d'Aulnay again at Port Royal in 1643. D'Aulnay and Port Royal finally won the war against La Tour with the attack on Saint John in 1645. After d'Aulnay died in 1650, La Tour returned to power in Acadia.

King William's War

The Maliseet people, from their main village at Meductic on the Saint John River, took part in many attacks and battles against New England during King William's War.

18th Century Conflicts

The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 officially ended the Queen Anne's War. One part of this treaty was that the French gave up their claim to peninsular Acadia (most of Nova Scotia) to the British. All of what later became New Brunswick, as well as "Île St-Jean" (Prince Edward Island) and "Île Royale" (Cape Breton Island) stayed under French control. Some Acadians living in Nova Scotia moved to these French-controlled areas as part of the Acadian Exodus.

Most Acadians now lived in the new British colony of Nova Scotia. The rest of Acadia (including the New Brunswick region) had few people. The main Acadian settlements in New Brunswick were at Beaubassin (Tantramar) and the nearby areas of Shepody, Memramcook, and Petitcodiac, which they called Trois-Rivière. There were also settlements in the Saint John River valley at Fort la Tour (Saint John) and Fort Anne (Fredericton).

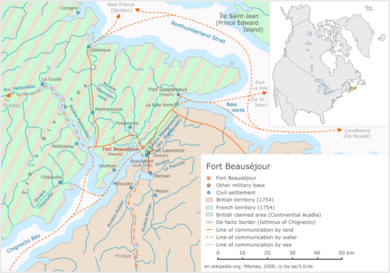

To protect the area, the French built several forts. These included Fort Nashwaak, Fort Boishebert, and Fort Menagoueche in the Bay of Fundy. In the southeast, they built Fort Gaspareaux and Fort Beauséjour. The British and New England troops captured Fort Beauséjour in 1755. Soon after, the Expulsion of the Acadians began. Even though continental Acadia stayed French, peninsular Acadia became British after the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). But the new owners were slow to fully take over. Until the final peace in the Americas with the Treaty of Paris (1763), there were small conflicts in the region.

The Maliseet people from Meductic on the Saint John River took part in many attacks and battles against New England during Father Rale's War. During Father Le Loutre's War, a fight between Acadian and Mi'kmaq militias and the British, many attacks and battles happened on the Isthmus of Chignecto.

Seven Years' War

Before 1755, Acadians helped in various military actions against the British. They also kept important supply lines open to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beauséjour. During the French and Indian War, the British wanted to stop any military threat from Acadians. They also wanted to cut off the vital supplies Acadians sent to Louisbourg. So, they moved Acadians away from Acadia.

After the Siege of Louisbourg (1758), the second part of the Expulsion of the Acadians began. British commanders led campaigns to remove Acadians from different areas. This included the St. John River Campaign and the Petitcodiac River Campaign. In the Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign (1758), the British wanted to clear Acadians from villages along the Gulf of St. Lawrence. This was to prevent them from interfering with the Siege of Quebec in 1759. Fort Anne fell during the St. John River Campaign. After this, all of what is now New Brunswick came under British control. France finally lost control of all its North American lands by 1760. The Treaty of Paris (1763) ended the wider wars between Britain, France, and Spain. This treaty recognized that France was no longer in North America.

British Colonial Times

After the Seven Years' War, most of what is now New Brunswick (and parts of Maine) became part of the colony of Nova Scotia. It was called Sunbury County. Its main town was Campobello. New Brunswick's location, away from the Atlantic coast, made it harder for new settlers to arrive right after the war. However, there were a few exceptions. For example, "The Bend" (today's Moncton) was founded in 1766 by Pennsylvania Dutch settlers. These settlers were supported by Benjamin Franklin's Philadelphia Land Company.

Other American settlements grew, mainly in former Acadian lands in the southeast. This was especially true around Sackville. An American settlement also grew at Parrtown (Fort la Tour) at the mouth of the Saint John River. English settlers from Yorkshire also arrived in the Tantramar region near Sackville before the Revolutionary War.

American Revolution

The American Revolutionary War directly affected the New Brunswick region. Several conflicts happened here. These included the Maugerville Rebellion (1776), the Battle of Fort Cumberland, the Siege of Saint John (1777), and the Battle at Miramichi (1779). The population did not grow much until after the American Revolution. Then, Britain convinced Loyalist refugees from New England to settle in the area by giving them free land. Some earlier American settlers in New Brunswick actually supported the American Revolution. For example, Jonathan Eddy and his militia attacked and surrounded the British fort at Fort Cumberland (which was renamed from Fort Beauséjour). This happened early in the American Revolution. The attack was only stopped when more troops arrived from Halifax.

Loyalists and New Brunswick's Creation

When the Loyalist refugees arrived in Parrtown (Saint John) in 1783, there was a strong need to organize the territory politically. The new Loyalists felt no loyalty to Halifax. They wanted to separate from Nova Scotia to avoid what they saw as democratic ideas in that city. They felt that Nova Scotia's government represented people who had supported the American Revolution. The Loyalists strongly disliked American and republican ideas. Colonel Thomas Dundas wrote from Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1786, that the Loyalists "have experienced every possible injury from the old inhabitants of Nova Scotia, who are even more disaffected towards the British Government than any of the new States ever were." These feelings, though perhaps exaggerated, helped lead to the colony being split.

The election of 1786 was very competitive. It showed two different ideas of loyalty to the British Empire. One was loyalty to the King and his appointed governors. The other was loyalty to the King, but with local matters handled by local people. Hundreds of people who protested a rigged election and signed a petition for a new election were arrested for rebellion. The meaning of loyalty was a big issue in Canadian politics in the 1800s. This event was similar to how people in the 13 American Colonies acted before 1775. They declared loyalty to the King and pride in being British, but also insisted on their rights and local rule.

British leaders at the time felt that the capital city (Halifax) was too far from the growing areas west of the Isthmus of Chignecto. They thought this made it hard to govern properly. So, they decided Nova Scotia should be split. As a result, the colony of New Brunswick was officially created on August 16, 1784. Sir Thomas Carleton became its first governor.

New Brunswick was named to honor the British king, King George III. He was from the House of Brunswick (a German royal family). Fredericton, the capital city, was also named for George III's second son, Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany. However, local people had suggested the name 'New Ireland'.

The choice of Fredericton (the former Fort Anne) as the capital surprised and upset the people of the larger town of Parrtown (Saint John). The reason given was that Fredericton's inland location made it safer from enemy (meaning American) attacks. However, Saint John became Canada's first official city. For over a century, it was one of the most important communities in British North America. From 1787 to 1791, Saint John was home to the former American general Benedict Arnold. He had switched sides to the British army. He was a tough businessman who often sued people and had a bad reputation before he left for London.

Loyalists brought the practice of slavery with them to New Brunswick. Many brought enslaved people when they left the American colonies. By the late 1700s, some people started to question this practice. In 1799, the New Brunswick Supreme Court heard two cases where enslaved people sued for their freedom. After almost a year, the court made a split decision in R v Jones and chose not to hear R v Agnew. This allowed slavery to continue. But public opinion began to change, and by 1820, slavery had mostly ended in New Brunswick. It was officially abolished in the colony by the British Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

19th Century Developments

Some Acadians who had been moved from Nova Scotia found their way back to "Acadie" in the late 1700s and early 1800s. They settled mostly along the eastern and northern coasts of the new colony of New Brunswick. There, they lived outside the established British communities.

The War of 1812 did not have a big effect on New Brunswick itself. However, there was some fighting in the Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Maine involving private ships and small British navy vessels. Forts like the Carleton Martello Tower in Saint John and the St. Andrew's Blockhouse on Passamaquoddy Bay were built, but no battles happened there. Locally, New Brunswickers got along well with their neighbors in Maine and the rest of New England, who generally did not support the war. There was even one time during the war when the town of St. Stephen lent its gunpowder to nearby Calais, Maine, across the St. Croix River, for their Fourth of July celebrations.

However, New Brunswick greatly helped the war effort in Upper Canada by sending troops. In the winter of 1813, the local 104th Regiment of Foot (New Brunswick) marched from Fredericton to Kingston. This was a very long journey, recorded in the diary of John Le Couteur. Once in Upper Canada, the 104th fought in some of the most important battles of the war. These included the Battle of Lundy's Lane, the Siege of Fort Erie, and the attack on Sacket's Harbour.

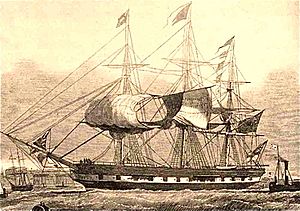

In 1819, the ship Albion left Cardigan, Wales, for New Brunswick. It carried the first Welsh settlers to Canada. On board were 27 families from Cardigan, many of whom were farmers.

Border Disputes

The border between Maine and New Brunswick was not clearly set by the Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the Revolutionary War. The border was argued over. People on both sides often used this unclear border to smuggle goods, especially in Passamaquoddy Bay. The illegal trade of Nova Scotia gypsum led to the "Plaster War" in 1820.

By the 1830s, competing lumber businesses and more immigration meant a solution was needed. The situation got so bad by 1842 that the governor of Maine called out his soldiers. British troops arrived in the region soon after. This whole event, called the Aroostook War, was peaceful. Thankfully, calm minds won, and the Webster-Ashburton Treaty settled the dispute. Some local people in the Madawaska region did not care much who controlled the area. When an official asked one resident of Edmundston which side he supported, he replied "the Republic of Madawaska". This name is still used today for the northwestern part of the province.

Economy in the 1800s

Throughout the 1800s, shipbuilding became the most important industry in New Brunswick. It started in the Bay of Fundy with shipbuilders like James Moran in St. Martins. Soon, it spread to the Miramichi. The ship Marco Polo, thought to be the fastest clipper ship of its time, was launched from Saint John in 1851. Famous shipbuilders like Joseph Salter helped build towns like Moncton. Industries based on natural resources, like logging and farming, were also important to New Brunswick's economy. This was true even after disasters like the 1825 Miramichi fire. From the 1850s to the end of the century, several railways were built across the province. This made it easier to get these inland resources to markets elsewhere.

Immigration in the 1800s

In the early 1800s, most immigrants came from western England and Scotland. Many also came from Waterford, Ireland, often after living in Newfoundland first.

A large number of Catholic settlers arrived in New Brunswick in 1845 because of the Great Famine in Ireland. They went to the cities of Saint John or Chatham. Chatham still calls itself the "Irish Capital of Canada" today. Established Protestants did not like the newly arrived Catholics. Until the 1840s, Saint John, the biggest city in New Brunswick, was mostly a Protestant community. Along with a decade of economic problems in New Brunswick, the arrival of poor, unskilled workers caused strong anti-immigrant feelings. The Orange Order, which was a small group until then, became a leader of these feelings. This led to tension between Orange Order members and Catholics. The conflict ended in a riot on July 12, 1849, where at least 12 people died. The violence decreased as Irish immigration slowed down.

Irish Migrants

Between 1815, when big industrial changes began in Europe, and Canadian Confederation in 1867, when immigration peaked, more than 150,000 immigrants from Ireland came to Saint John. Those who came earlier were mostly skilled workers. Many stayed in Saint John and helped build the city. But when the Great Famine raged between 1845 and 1852, huge numbers of famine refugees arrived. It is thought that between 1845 and 1847, about 30,000 people arrived. This was more people than were living in the city at the time. In 1847, called "Black 47," one of the worst years of the Famine, about 16,000 immigrants arrived. Most were from Ireland. They came to Partridge Island, the immigration and quarantine station at the mouth of Saint John Harbour. However, thousands of Irish people were already living in New Brunswick before these events, mainly in Saint John and the Miramichi River valley.

After the British colony of Nova Scotia was divided in 1784, New Brunswick was first named New Ireland. Its capital was planned to be in Saint John.

The Miramichi River valley received many Irish immigrants in the years before the Great Famine. These settlers were often better off and more educated than those who arrived later out of desperation. Although they came after the Scottish and French Acadians, they made their way in this new land. They often married Catholic Highland Scots, and to a lesser extent, Acadians. Some, like Martin Cranney, held elected office and became natural leaders for their growing Irish community after the famine immigrants arrived. The early Irish came to the Miramichi because it was easy to reach by lumber ships stopping in Ireland before returning to Chatham and Newcastle. It also offered jobs, especially in the lumber industry. They commonly spoke Irish. In the 1830s and 1840s, there were many Irish-speaking communities along the New Brunswick and Maine border.

The Irish language was still spoken in New Brunswick communities into the 1900s. The 1901 census asked about people's mother tongue, meaning the language commonly spoken at home. Several people and a few families in the census said Irish was their first language and was spoken at home. These people had less in common in other ways; some were Catholic and some were Protestant.

Canadian Confederation

New Brunswick was one of the four original provinces that joined Canada in 1867. The Charlottetown Conference in 1864 was first meant to discuss a Maritime Union of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. But worries about the American Civil War and Fenian activity near the border led to interest in a larger union. This interest came from the Province of Canada (which used to be Upper and Lower Canada, later Ontario and Quebec). The Canadians asked the Maritimers to change the meeting's plan.

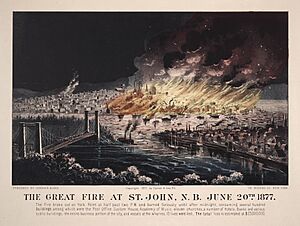

After Confederation, those who had worried were proven right. New Brunswick (and the rest of the Maritimes) suffered a big economic slowdown. New national policies and trade barriers created by Confederation disrupted the old trading relationships between the Maritime Provinces and New England. In 1871, the local government sent a group to Ottawa to ask for "better terms." The situation in New Brunswick got worse because of the Great Fire of 1877 in Saint John. The wooden sailing shipbuilding industry also declined. A worldwide economic downturn, caused by the Panic of 1893, greatly affected the local export economy. Many skilled workers lost their jobs and had to move west to other parts of Canada or south to the United States. But as the 1900s began, the province's economy started to grow again. Manufacturing became stronger with the building of several textile mills across the province. In the important forestry sector, the small sawmills that were spread across the province were replaced by larger pulp and paper mills. Still, unemployment remained quite high, and the Great Depression caused another setback. Two powerful families, the Irvings and the McCains, became important after the depression. They began to modernize and combine different parts of the provincial economy.

World War II

After Canada joined World War II, 14 army units were formed, in addition to The Royal New Brunswick Regiment. They first fought in the Italian campaign in 1943. After the Normandy landings, they went to northwestern Europe, along with The North Shore Regiment. The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, a program to train Allied pilots, set up bases in Moncton, Chatham, and Pennfield Ridge. A military typing school was also set up in Saint John. Before the war, New Brunswick was not very industrial. But during the war, it became home to 34 factories working on military contracts. The province received over $78 million from these contracts. Other production centers also helped with all parts of the war effort.

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King had promised there would be no conscription (forced military service). But he later asked the provinces if they would release the government from this promise. New Brunswick voted 69.1% yes. The policy was not put into action until 1944, which was too late for many of the conscripted soldiers to be sent to war. New Brunswick lost 1808 people in the Army, RCAF (Air Force), and RCN (Navy).

After World War II

The Acadians had mostly managed on their own along the northern and eastern coasts since they were allowed to return after 1764. They were usually separate from the English speakers who were most common in the rest of the province. Government services were often not available in French. The roads and other services in mostly French-speaking areas were not as developed as in other parts of the province. This changed when Louis Robichaud became premier in 1960. He started an ambitious Equal Opportunity Plan. This plan put education, rural road maintenance, and health care under the provincial government's control. The government insisted on equal services for all areas of the province. Teachers were paid the same, no matter how many students they had.

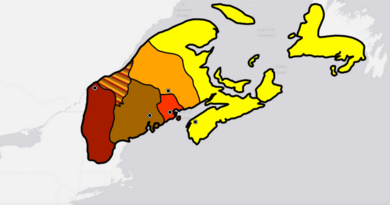

County councils were ended. Rural areas outside cities, towns, and villages came directly under provincial control. The 1969 New Brunswick Official Languages Act made French an official language, equal to English. This caused some tension between language groups. The strong Parti Acadien was briefly popular in the 1970s. English-speaking groups pushed to cancel the language reforms in the 1980s, led by the Confederation of Regions Party. By the 1990s, most of these language tensions had disappeared. However, these tensions came back around 2018 with the creation of the People's Party of Canada.

21st Century New Brunswick

In the early 2020s, during the COVID-19 pandemic, New Brunswick's population grew a lot. This was mainly due to people moving from other Canadian provinces, especially Ontario, and from immigrants coming to Canada. By 2023, the province had seen more population growth in the previous two years than in the past 29 years combined. In 2022, according to an analyst from Statistics Canada, New Brunswick had its highest population growth in a single year since it joined Confederation in 1867. The next year, New Brunswick broke that record again. This increase in population has caused the province's average age to drop for the first time in over 50 years.

In 2023, a major change to local government happened. Several local service districts in the province were combined.

See Also

- Military history of the Mi’kmaq People

- Military history of the Maliseet people

- Military history of the Acadians

- History of the Acadians

- Aboriginal communities in New Brunswick

- List of New Brunswick premiers

- List of New Brunswick lieutenant-governors

- Aboriginal place names in New Brunswick

- List of historic places in New Brunswick

- List of National Historic Sites of Canada in New Brunswick

- History of Moncton

- Province of Massachusetts Bay

- The Officers' Quarterly

General:

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |