Roman Egypt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Province of Egypt

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of the Roman Empire | |||||||||||

| 30 BC – 641 AD

Under Palmyrene rule; 270–273 Sasanian occupation; 619–628 |

|||||||||||

Province of Aegyptus in AD 125 |

|||||||||||

| Capital | Alexandria | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

|

• 1st century AD

|

4 to 8 million. | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity Late antiquity |

||||||||||

|

• Conquest of Ptolemaic Kingdom

|

30 BC | ||||||||||

|

• Formation of the Diocese

|

390 | ||||||||||

| 641 | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | Egypt | ||||||||||

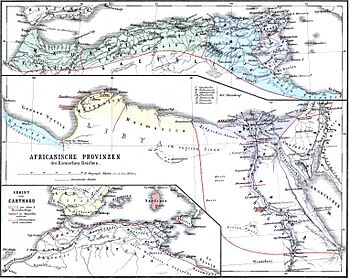

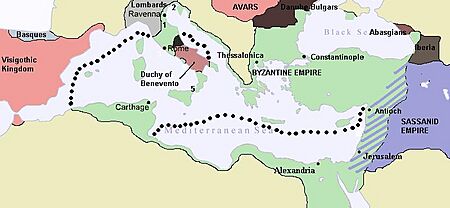

Roman Egypt was a special part of the Roman Empire for a long time, from 30 BC to AD 641. It covered most of what we now call Egypt, except for the Sinai Peninsula. To its west was Crete and Cyrenaica, and to its east were Judaea and later Arabia Petraea.

Rome took control of Egypt in 30 BC. Egypt then became a very important province. It was a major supplier of grain for the entire Roman Empire. Egypt was also the richest Roman province outside of Italy. Its capital, Alexandria, was a huge port and the second-largest city in the Roman Empire. We don't know exactly how many people lived in Roman Egypt, but estimates suggest between 4 and 8 million.

At first, three Roman armies were stationed in Egypt. Later, this was reduced to two, along with other smaller groups of soldiers called auxilia. The main town in each area, called a nome, was known as a metropolis. These cities had special rights. People in Roman Egypt were divided by their social class and background. Most people were farmers living in villages. They spoke the Egyptian language, which changed into Coptic under Roman rule. In the cities, people spoke Koine Greek and followed Greek culture. However, people could move up in society, and many moved to cities. Both city and country people were involved in trade and could read and write well. In AD 212, a law called the Constitutio Antoniniana gave Roman citizenship to all free Egyptians.

A big sickness, the Antonine Plague, hit in the late 100s AD. But Roman Egypt got better by the 200s. It avoided many problems of the Crisis of the Third Century. However, it was taken over by the Palmyrene Empire after Zenobia invaded in 269. The Roman emperor Aurelian (270–275) took Alexandria back and recovered Egypt. Later, two people, Domitius Domitianus and Achilleus, tried to rule Egypt against Emperor Diocletian (284–305). Diocletian got Egypt back in 297–298. He then made big changes to how the province was run and its economy. This was also when Christianity in Egypt grew a lot. After Constantine the Great took control in AD 324, emperors supported Christianity. The Coptic language became important among Egyptian Christians.

Under Diocletian, the border moved south to the First Cataract of the Nile at Syene (Aswan). This southern border was mostly peaceful for many centuries. Constantine introduced the gold solidus coin, which made the economy more stable. More land became privately owned in the 400s and 500s. Some large farms were owned by Christian churches. The First Plague Pandemic arrived in the Mediterranean Basin in 541. It started at Pelusium in Roman Egypt.

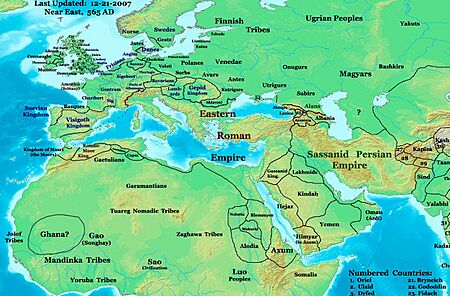

Egypt was conquered by the Sasanian Empire in 618. They ruled for ten years. But it was given back to the Eastern Roman Empire in 628. Egypt stopped being part of the Roman Empire forever in 641. This happened after the Muslim conquest of Egypt, when it became part of the Rashidun Caliphate.

Contents

How Roman Egypt Began

The Ptolemaic Kingdom had ruled Egypt since the time of Alexander the Great. The last Ptolemaic queen, Cleopatra VII, supported Julius Caesar during his wars. After Caesar was killed, Cleopatra joined forces with Mark Antony, a powerful Roman leader. In the final war of the Roman Republic (32–30 BC), Antony and Cleopatra fought against Octavian. Octavian won the important Battle of Actium and then invaded Egypt. Antony and Cleopatra killed themselves, and the Ptolemaic Kingdom ended. Octavian took Egypt as his own.

In 27 BC, Octavian was given the special name Augustus. Egypt officially became a province of the new Roman empire. Augustus and later Roman emperors ruled Egypt as if they were the Roman pharaoh. The old Ptolemaic government was changed a lot, but some parts stayed the same. The Greek-Egyptian legal system continued, but under Roman law. The money minted in Alexandria, called tetradrachm, was still used. But its value was made equal to the Roman denarius. Augustus also changed land ownership. More people could own land privately, which was rare before. Local government was reformed, requiring landowners to serve in public roles. The priests of the Ancient Egyptian deities and Greek gods kept their temples and special rights. In return, they also honored the Roman emperors.

Roman Rule in Egypt

When Rome took over Egypt, they made many changes. The Romans generally favored the Greeks and their culture over Egyptian traditions. Some old titles and jobs from the Ptolemaic era stayed, but their roles often changed.

The Romans made big changes to how Egypt was run. Their goal was to make things very efficient and collect as much money as possible. The governor of Egypt, called the praefectus Aegypti, was in charge of military safety, money, taxes, and justice.

For the first 300 years, one Roman governor controlled all of Egypt. This governor was called the "prefect of Alexandria and Egypt." This double name showed that Alexandria was special and not quite part of the traditional Egyptian regions.

The Roman emperor chose the governor of Egypt for several years. Unlike other Roman provinces, Egypt's governor and main officials were of a lower rank, called equestrian. This was to prevent the governor from becoming too powerful. The prefect of Egypt had similar powers to a general. He was also in charge of collecting certain taxes and making sure grain was shipped from Egypt to Rome. This was a very important job. The governor of Egypt was a highly paid and respected position.

The governor could make laws and order punishments. His power ended when a new governor arrived in Alexandria. At first, three Roman armies were in Egypt, but later only two. The governor also held regular meetings to handle legal cases and check on officials. More than 60 laws made by Roman governors of Egypt still exist today.

Other officials, also of equestrian rank, helped the governor. These included financial officers and legal experts. From the time of Emperor Hadrian (117–138), the prefect's financial powers were given to other officials. These included a chief financial officer and a chief priest for the temples.

Some officials were also former slaves who had been freed by the emperor. They managed state property and monopolies. Unfortunately, we don't know much about these roles because few records survived.

Outside Alexandria, the country was divided into traditional regions called nomoi. The main cities in these regions were governed by local leaders. These leaders often paid for public buildings themselves. The prefect appointed a strategos (general) for each nome. These strategoi were civilian leaders, not military. They were usually from the Egyptian upper classes and managed the region for the prefect. They were responsible for their actions for several years.

Each strategos had a royal scribe who handled financial matters. These scribes kept very detailed records. The nomoi were grouped into Upper and Lower Egypt. Each group had a chief officer called an epistrategos. Their main job was to connect the prefect in Alexandria with the local strategoi.

Each village had a scribe who worked for about three years. They had to be literate and informed officials about people who needed to do public service without pay. Other local officials collected taxes or managed grain. By the time of Emperor Trajan (98–117), this system of unpaid public service was widespread. People often tried to avoid these duties.

In the early 300s, Egypt was divided into smaller provinces. Separate civilian and military leaders were put in place. Emperor Justinian later combined these powers again in 538. By then, local self-rule had mostly disappeared. Soldiers became more visible in daily life.

Roman Military in Egypt

The Roman army in Egypt was organized much like armies elsewhere in the Roman Empire. Roman citizens joined the main armies, called Roman legions. Non-citizens joined the smaller groups called auxilia.

Egypt was special because its army was led by the praefectus Aegypti, an equestrian official. In other provinces, senators led the armies. This rule was set by Augustus. It meant that the legion commanders in Egypt were also of equestrian rank. This prevented any single general from becoming too powerful, like Mark Antony had.

The main Roman army base was in Nicopolis, near Alexandria. This was not in the traditional heart of Egypt around Memphis. Alexandria was the second-largest city in the Mediterranean. It was the cultural center of the Greek East. Few records from Alexandria survive, so we don't know much about the daily lives of soldiers there. Most records come from villages in Middle Egypt. They focus on local issues, not military matters.

We know about the auxilia in Egypt from six bronze Roman military diplomas. These certificates were given to soldiers after 25 or 26 years of service. They granted Roman citizenship and the right to marry. The army in Egypt used more Greek than in other provinces.

The main army of Egypt was at Nicopolis in Alexandria. At least one legion was always there, along with strong cavalry forces. These troops protected the governor and could quickly move to any trouble spot. Alexandria also had the Roman Navy's fleet. In the 100s and 200s, about 8,000 soldiers were in Alexandria. This was a small part of the city's huge population.

At first, Egypt had three legions: the Legio III Cyrenaica, the Legio XXII Deiotariana, and one other. The third legion left before 23 AD. The legions were stationed at Nicopolis, Egyptian Babylon, and possibly Thebes. After 119 AD, the III Cyrenaica left. The XXII Deiotariana also moved later. The Legio II Traiana arrived before 127/8 AD and stayed for two centuries.

The number of auxilia soldiers was stable for a long time. It increased slightly in the late 100s. Some units stayed in Egypt for centuries. Three or four cavalry units, each with about 500 horsemen, were in Egypt. There were also seven to ten infantry units, each with about 500 soldiers. Some were mixed units with both infantry and cavalry. Besides Alexandria, at least three groups of soldiers guarded the southern border. They protected Egypt from enemies to the south and from rebellions in the Thebaid region.

Many Roman soldiers in Egypt were recruited locally. This was true for both non-citizen auxilia and citizen legionaries. More and more soldiers were from Egypt during the Flavian and Severan dynasties. About a third of these were children of soldiers, raised near the army base. Only a small number were Alexandrian citizens. Egyptians joining the army took Roman-style Latin names.

Archaeological finds have shown details about soldiers' lives in the Eastern Desert. They were stationed along trade roads and at stone quarries. Another Roman outpost was on Farasan Island in the Red Sea.

Society in Roman Egypt

The social structure in Roman Egypt was unique and complex. The Romans kept many of the old ways from the Ptolemaic period. However, the Romans saw Greeks in Egypt as "Egyptians," which both Greeks and native Egyptians would have disagreed with. Jews, who were very influenced by Greek culture, had their own separate communities.

Most people were farmers. Many worked on land owned by temples or the state, paying high rents. The biggest cultural difference was between the villages, where Egyptian was spoken, and the cities, where Greek was spoken. This difference remained even after all free Egyptians became Roman citizens in 212 AD. However, people could move up in society. Many moved to cities, and trade was common. Many farmers could read and write Greek.

The Romans created a social ladder based on a person's background and where they lived. Roman citizens were at the top. Greek citizens of Greek cities had the next highest status. Rural Egyptians were at the bottom. In between were people from the main cities, who were usually of Greek background. It was very hard to become a Roman citizen or move up in rank.

One way to move up was to join the army. Only Roman citizens could join the legions, but many Greeks found ways in. Native Egyptians could join the auxiliary forces and become citizens after their service. Different groups paid different taxes. Roman citizens and Alexandrians did not pay the poll tax. Hellenized people in the main cities paid a low poll tax, while native Egyptians paid more. Native Egyptians could not serve in the army. There were other legal differences between the classes. In the cities, a wealthy Greek land-owning group controlled much of Egypt in the 100s and 200s.

The social structure was closely tied to the government. The system of appointing strategoi to govern regions continued until the 300s. Town councils, called boulai, were formally created by Septimius Severus. Under Diocletian, these councils gained important responsibilities. Augustus also introduced a system of forced public service based on wealth. The Romans also brought in a poll tax, similar to what the Ptolemies had. But Romans gave lower rates to citizens of the main cities. Records from Oxyrhynchus show much about the social structure in these cities.

Alexandria and its citizens had special rights. The capital city had higher status and more privileges. To become an Alexandrian citizen, both parents had to be Alexandrian citizens. Alexandrians were the only Egyptians who could become Roman citizens.

If an ordinary Egyptian wanted to become a Roman citizen, they first had to become an Alexandrian citizen. During Augustus's time, new city communities with Greek land-owning leaders were created. These leaders had more power and self-rule than the Egyptian population. Greek citizens could join special clubs called gymnasiums if their parents were also members. There was also a council of elders called the gerousia. These Greek groups formed an elite class of citizens. The Romans relied on these elites to provide city officials and educated administrators. These elites also paid lower poll taxes than native Egyptians. Alexandrians were famously exempt from poll taxes and paid lower land taxes. Egyptian landowners paid much more in taxes than the elites and Alexandrians.

These privileges even extended to punishments. Romans were protected from certain physical punishments. Native Egyptians were whipped. Alexandrians were beaten with a rod instead. Alexandria had the highest status, but other Greek cities like Antinoöpolis also had similar privileges, such as not paying poll taxes. All these changes meant Greeks were treated as allies, while native Egyptians were treated as a conquered people.

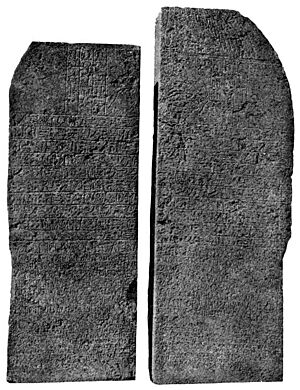

A document called the Gnomon of the Idios Logos shows how law and social status were connected. It listed revenues, mostly fines and property seizures, that only certain groups were subject to. It also confirmed that a freed slave took on their former master's social status. This document shows how the Romans used money and status to control society.

Economy of Roman Egypt

The economic resources of Egypt were similar to those under the Ptolemies. However, the Romans created a much more complex tax system. Taxes were collected in both money and goods, especially on land. Many small taxes and customs duties were also collected by appointed officials.

A huge amount of Egypt's grain was shipped north to feed Alexandria and to be sent to the Roman capital. People often complained about unfair taxes and demands.

For land, the Romans introduced a difference between private and public lands. Before, most land belonged to the king. Now, there were many types of land ownership. Land status depended on its use and how it was owned. The three main types from the Ptolemaic system continued: sacred land for temples, royal land for the state, and "gifted land" leased out.

The Roman government encouraged private land ownership and private businesses. Low tax rates favored private owners. Poorer people worked as tenants on state-owned land or on land belonging to the emperor or rich landlords. They paid high rents.

Overall, the economy, even in villages, used a lot of money and was very complex. Goods were bought and sold with coins on a large scale. In towns and bigger villages, industries and businesses grew, connected to farming. Trade, both inside and outside Egypt, was at its highest in the 1st and 2nd centuries.

By the late 200s, there were big problems. The value of Roman money went down, and people lost trust in it. The government itself started demanding more taxes in goods, which it gave directly to the army. Local councils were not managing things well. Emperors Diocletian and Constantine I had to make big reforms.

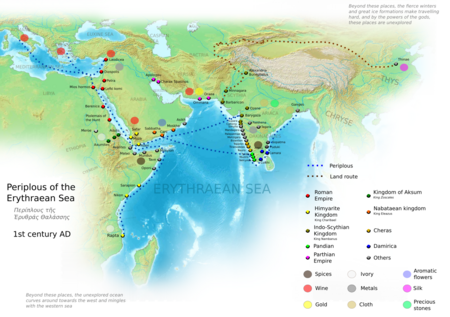

There are many signs of Roman trade with India during this time. This was especially true between Roman Egypt and India. The Kushan Empire ruler Huvishka (150–180 CE) even put the Roman-Egyptian god Serapis on his coins. This suggests that Huvishka had strong ties to Roman Egypt, which might have been a key market for goods from his empire.

Roman Architecture in Egypt

In the main cities of the nomoi, Roman public buildings were built by local leaders. Most of these buildings have not survived, but they were likely built in the classical Greek-Roman style. Important remains include two Roman theaters at Pelusium, a temple of Serapis at Thebes, and a triumphal arch at Philae. This arch was dedicated to Emperor Augustus and the goddess Roma. Besides a few stone blocks, much of what we know about Roman architecture comes from drawings made during Napoleon's campaign in Egypt. Many of these ruins have since disappeared.

Most cities were probably built with a grid pattern, like Alexandria. This pattern had main roads running north-south and east-west.

The oldest known Christian church buildings in Egypt are at the village of Kellis. A large church was built there in the time of Constantine. All these early churches faced east. Churches were built quickly after Constantine's victory. Even small towns had churches in the 300s. The earliest large church that still has remains is at Antinoöpolis. It was a long church with five aisles.

In the late 300s, churches in monasteries started to have rectangular altars instead of round ones. In the 400s, different styles of large churches appeared. Churches on the coast had three or five aisles. In Middle and Upper Egypt, churches often had columns all around them. In eastern Egypt, columns were emphasized, and the altar area had a special arch.

A cross-shaped design was used in cities like Abu Mena. In the mid-400s, a very large church was built at Hermopolis Magna. At the Coptic White Monastery at Sohag, the 400s church had a special three-lobed altar area. This design was also found in other places. The tomb of the White Monastery's founder, Shenoute, also had this design. Some stones for the White Monastery were taken from older Egyptian buildings nearby. The main church looked like an Egyptian temple from the outside. The nearby Red Monastery has the most detailed painted decorations from this period.

Religion in Roman Egypt

Honoring the Emperors

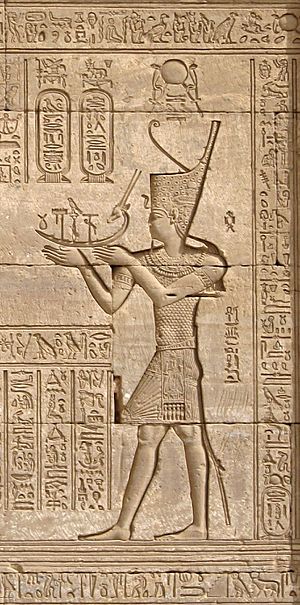

The worship of Egypt's rulers stopped when the Ptolemaic dynasty fell. After Rome conquered Egypt, Augustus started a new way to honor the Roman emperors. The "Roman people" were now the rulers of Egypt. Emperors were not crowned pharaohs in the old way. There is no clear sign that emperors were regularly included in the traditional Egyptian gods' worship. Instead, Augustus was linked to Zeus Eleutherios (the liberator). This was like Alexander the Great, who was said to have "liberated" Egypt.

Still, in 27 BC, a high priest of Ptah was appointed in Memphis under Augustus. He was called a "priest of Caesar." Augustus was honored with a cult in Egypt before he died. There is also evidence that Nero and Hadrian were worshipped while they were still alive. However, while alive, emperors were usually honored with offerings "for their health." They were usually worshipped as gods only after they died. For legal reasons, people had to swear oaths in the emperor's name.

An official called the archiereus for Alexandria and All Egypt was in charge of this imperial worship. He also managed Egypt's temples and the worship of Serapis. This archiereus was a Roman citizen. The official cult in Egypt was different from other provinces. The goddess Roma, linked to the Roman Senate, was not introduced. This was because Egypt was an imperial province, outside the Senate's direct power.

Each nome also had an archiereus. These high priests were from the local elite. They were responsible for maintaining imperial temples and cults in their cities. These officials mainly organized the imperial cult. The traditional local cults already had their own priests. Throughout Egypt, altars were set up in special temples to worship the deified Emperor Augustus. These temples also had administrative roles. However, there is little evidence that emperors were widely worshipped in private homes. Alexandrians were often against the emperors themselves.

The way emperors were worshipped, which started with Augustus, continued until Constantine the Great. Emperor Trajan's wife, Plotina, was made a goddess after she died. At Dendera, in a temple for Aphrodite, she was linked to the Egyptian goddess Hathor. This was the first time an imperial family member, besides the emperor, was included in the Egyptian gods. Unlike the Ptolemaic royal cult, which used the Egyptian calendar, the imperial cult days, like emperors' birthdays, followed the Roman calendar.

Worship of Serapis and Isis

Serapis was a god that combined Greek and Egyptian features. He was created by Ptolemy I at the start of the Ptolemaic period. Serapis took on the role of Osiris as the god of the afterlife. He was the husband of the goddess Isis and father of Horus. Emperors were sometimes shown as Serapis. Serapis was known for his Greek clothes, long hair, beard, and a flat-topped crown. Emperor Caracalla even called himself "Philosarapis" to show his devotion.

The Mysteries of Isis, a special religious group, became very popular. Isis was the most important female goddess. She was seen as a creator goddess. As Isis lactans, she was an image of motherhood, feeding her baby Harpocrates. As Isis myrionymos, she was a goddess of magic.

In Roman Egypt, the archiereus for Alexandria and All Egypt oversaw the cult. Temples of Serapis, called serapea, were found throughout Egypt. The oldest was at Memphis, and the largest was the Serapeum of Alexandria. The holy family of Serapis, Isis, and Harpocrates was worshipped across the empire. By the 300s, this cult was the most popular religion after Christianity.

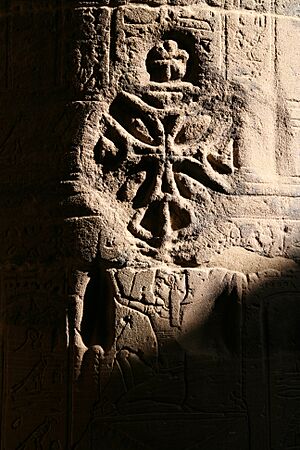

Temples

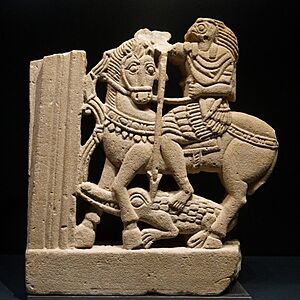

The emperor-appointed archiereus was in charge of managing all temples, not just those for the imperial cult. He controlled who could become priests in Egyptian cults. Emperors were shown in traditional pharaonic clothes on temple carvings. Similarly, Egyptian gods were sometimes shown wearing Roman military clothes, especially Anubis and Horus.

We can learn a lot about Egyptian temples in Roman times from places like Bakchias and Tebtunis. Records show that temples sometimes helped each other when they needed staff. But they also competed for influence. When temples had problems with authorities, it was usually with local officials. Roman governors would step in to help resolve these issues.

The early Roman emperors, like Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero, all supported religious sites. They sponsored monuments at places like Dendera, Edfu, and Karnak. Emperor Domitian was shown in many temple scenes, especially in Upper Egypt. His name was sometimes removed after his death.

After Domitian, Emperor Trajan continued to support Egyptian cults. His support is recorded at Dendera, Esna, and Philae. During Hadrian's visit to Egypt in 130–131, he founded the city of Antinoöpolis. This was in honor of his partner Antinous, who drowned in the Nile. Hadrian also ordered the Via Hadriana to be built. This road connected Antinoöpolis to the Red Sea.

Emperor Antoninus Pius also sponsored building work at temples. His reign saw the last major building work on Egyptian temples. After him, there were fewer new temple buildings. This was probably due to a lack of money and political problems.

Emperor Septimius Severus and his family were honored in a relief at Esna during their visit in 199–200. After his son Caracalla murdered his brother Geta, Geta's image was removed from the monument. Caracalla later massacred a group from Alexandria and allowed his army to loot the city.

New temple building and decoration stopped completely in the early 200s. The last Roman emperor recorded in hieroglyphic script was Maximinus Daza. The last known hieroglyphic inscription was from 394 AD at Philae.

Caligula allowed the worship of Egyptian gods in Rome, which Augustus had forbidden. Domitian built new temples to Isis and Serapis in Rome. After Hadrian's visit, there was a general interest in Egyptian culture in the Roman Empire. Hadrian's villa even had an Egyptian-themed area.

Christianity in Egypt

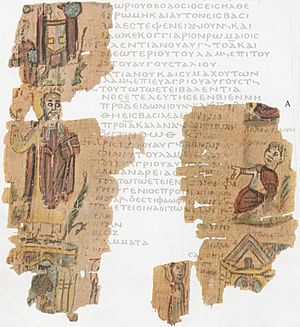

The New Testament does not say that any apostles visited Alexandria or Egypt. However, Egyptian and Alexandrian Jews are mentioned in the Book of Acts. Some believe Christianity arrived in Egypt in the 1st century, but there is no clear proof. The earliest history of Christianity in Alexandria comes from the 3rd and 4th centuries. It claims that Mark the Apostle visited Egypt. This was part of an effort to connect Alexandria to the early Christian leaders. Christianity likely came to Egypt through Greek-speaking Jews in Alexandria.

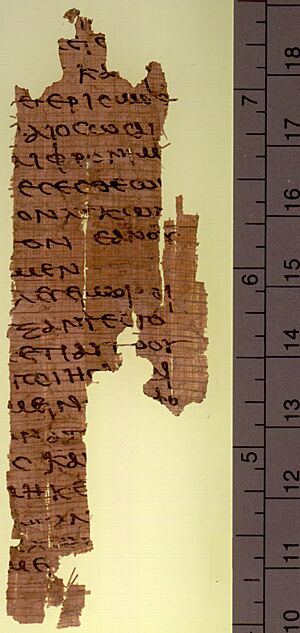

The earliest clear evidence of Christianity in Egypt is a letter from the early 200s. It uses Christian terms. Another record from the same time mentions an "Antonios Dioscoros son of Origen, Alexandrian," who is noted as a Christian. He was likely of high social status. Outside Alexandria, there is little evidence of Christianity in the 100s, except for some Bible fragments. Many of these were in book form, called codices, which Christians preferred.

By 200 AD, Alexandria was a major Christian center. Christian writers like Clement of Alexandria and Origen lived and taught there. In 313, Emperor Constantine I ended the persecution of Christians. Over the 400s, the old pagan religions lost followers. Paganism continued secretly for decades. The last law against paganism was in 435. But carvings at Philae show that Isis was still worshipped there in the 500s. Many Egyptian Jews became Christians, but many others did not. This made them the only large religious minority in a Christian country.

Soon after gaining freedom, the Egyptian Church faced big disagreements. Alexandria became the center of the first major split in the Christian world. This was between the Arians, led by the priest Arius, and their opponents, led by Athanasius. Athanasius became Archbishop of Alexandria in 326. The First Council of Nicaea rejected Arius's ideas. The Arian disagreement caused riots and rebellions for most of the 300s. During one of these, the great temple of Serapis, a pagan stronghold, was destroyed. Athanasius was removed and reinstated as Archbishop many times.

Many important Christian writings came from Egypt. Egypt had a long history of religious thought. This allowed different religious views to grow there. Besides Arianism, other beliefs like Gnosticism and Manichaeism also found followers. Another important development was monasticism, where people like the Desert Fathers left the material world to live simply and devote themselves to the Church.

Egyptian Christians embraced monasticism with such passion that Emperor Valens had to limit how many men could become monks. Egypt then spread monasticism to the rest of the Christian world. During this time, Coptic also developed. This was a form of the ancient Egyptian language written with the Greek alphabet. It was first used to say magical words correctly in pagan texts. But Christians soon used Coptic to spread the gospel to native Egyptians. It became the main language for Egyptian Christian services and still is today.

Christianity eventually spread west to the Berbers and south to Nubia. The Coptic Church was established in Egypt. Since Christianity mixed with local traditions, it did not fully unite the people against the Arab forces in the 600s and 700s.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 400s further separated Egyptian Romans from Roman culture. This sped up the growth of Christianity. As Christianity succeeded, old pharaonic traditions were mostly abandoned. With no Egyptian priests, no one could read the hieroglyphs anymore. Temples were turned into churches or left to the desert.

Cyril, the leader of the church in Alexandria, convinced the city's governor to expel the Jews in 415. This was after Jews were accused of attacking Christians. The murder of the philosopher Hypatia in March 415 marked a big change for classical Greek culture in Egypt. But philosophy still thrived in Alexandria in the 500s. Another split in the Church caused long-lasting problems. This may have made Egypt feel distant from the Empire. Many papyrus finds show that Greek culture and institutions continued at different levels.

The new religious disagreement was about Jesus's human and divine nature. The question was whether he had two natures or a combined one. This was enough to divide an empire. The Miaphysite disagreement started after the First Council of Constantinople in 381. It continued long after the Council of Chalcedon in 451. This council ruled that Christ was "one person in two natures."

Many Miaphysites claimed they were misunderstood. They said there was no real difference between their view and the Chalcedonian view. They believed the Council of Chalcedon ruled against them for political reasons. The Church of Alexandria separated from the Churches of Rome and Constantinople over this issue. This created the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, which is still very important in Egypt today. Egypt and Syria remained strongholds of Miaphysite belief. Organized resistance to the Chalcedonian view was not stopped until the 570s.

History of Roman Egypt

Early Roman Egypt (30 BC–4th Century)

The province of Egypt was created in 30 BC. This happened after Octavian, who later became Emperor Augustus, defeated Mark Antony. He removed Queen Cleopatra and added the Ptolemaic Kingdom to the Roman Empire.

The first governor of Egypt, Gaius Cornelius Gallus, brought Upper Egypt under Roman control. He also set up protection for the southern border region.

The second governor, Aelius Gallus, tried to conquer parts of Arabia but failed. The Red Sea coast of Egypt was not fully controlled by Rome until Emperor Claudius's time. The third governor, Gaius Petronius, cleaned up the canals for irrigation. This helped farming grow again. Petronius even led a campaign into what is now central Sudan against the Kingdom of Kush. Its queen, Imanarenat, had attacked Roman Egypt. Petronius destroyed the city of Napata but did not gain lasting control.

The reigns of Tiberius, Caligula, and Claudius were mostly peaceful in Egypt. There were some fights between Greeks and Jews in Alexandria. Claudius refused Alexandria's request for self-rule. He tried to calm the unrest between Greeks and Jews. Under Nero, an expedition to Meroë was planned. But plans for an invasion were stopped by the First Jewish–Roman War in Judaea.

The first governor of Egypt from Alexandria was Tiberius Julius Alexander. He was governor during the Year of the Four Emperors. He declared Vespasian emperor in Alexandria in July 69 AD. This governor was of Greek-Jewish background. Egypt's grain harvest was very important to Rome. This helped Vespasian gain control over the whole empire.

From Nero's time, Egypt had a century of prosperity. Religious conflicts between Greeks and Jews caused many problems, especially in Alexandria. After Jerusalem was destroyed in 70 AD, Alexandria became a major center for Jewish religion and culture.

Vespasian was the first emperor since Augustus to visit Egypt. In Alexandria, he was hailed as pharaoh. He was called the son of the god Amun and an incarnation of Serapis. Vespasian showed his divine power by miraculously healing a blind and crippled man.

(Graeco-Roman Museum)

Osiris-Antinous

In 114, during Trajan's reign (98–117), unrest broke out among Jews in Alexandria. This happened after a Messiah was announced in Cyrene. The uprising was defeated, but a revolt continued in the countryside between 115 and 117. This Kitos War involved Greeks and Egyptian farmers fighting against the Jews. It ended with the destruction of the Alexandrian Jewish community. The city of Oxyrhynchus celebrated its survival for at least eighty years.

During Hadrian's reign (117–138), an Egyptian revolt started in 122. It was quickly stopped. Hadrian himself toured Egypt for eight to ten months in 130–131. He took a Nile cruise and hunted lions. He also founded the city of Antinoöpolis where his partner Antinous drowned. This city had Greek citizenship rights. Hadrian also ordered the Via Hadriana, connecting Antinoöpolis to the Red Sea.

In 139, at the start of Antoninus Pius's reign (138–161), a special event happened. The Sothic cycle ended, meaning the star Sirius rose with the Egyptian New Year for the first time in 1,460 years. The emperor's coins showed the phoenix to celebrate this good sign. Antoninus Pius visited Alexandria and built new gates and a hippodrome. But in 153, a riot in Alexandria killed the governor.

The terrible Antonine Plague affected Egypt from 165 to 180. Mass graves from this time have been found. A revolt of native Egyptians from 171 was only stopped in 175 after much fighting. This "Bucolic War" was led by Isidorus. He had defeated the Roman army in Egypt. Control was restored by Avidius Cassius, who then declared himself emperor. But he was defeated and killed. Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161–180) restored peace when he visited Alexandria in 176.

Marcus Aurelius's successor Commodus (176–192) had Avidius Cassius's family killed. After Commodus's own murder, Pertinax became emperor in 193. News of this reached Egypt slowly. Pescennius Niger (193–194) was recognized as emperor in Egypt. Egypt ignored the claims of Didius Julianus in Rome.

Following Hadrian's path, Septimius Severus toured Egypt in 199–200. He visited the Colossi of Memnon and ordered them repaired. This stopped the statues from "singing." New local councils were created for Alexandria and each main city in 200/201. This was probably to improve tax collection.

Caracalla (198–217) gave Roman citizenship to all Egyptians in 212. This was part of the Constitutio Antoniniana. Many Egyptians took the emperor's name, "Aurelius." However, citizenship was less valuable and came with more taxes. Caracalla murdered his brother Geta. He then massacred Alexandria's welcoming group and allowed his army to loot the city. He also banned Egyptians from entering Alexandria, except for religious or trade reasons.

Macrinus (217–218) became emperor after assassinating Caracalla. He sent a new governor to Egypt. When news of Macrinus's death reached Alexandria, the people revolted. They killed the senator and forced out the governor. Elagabalus (218–222) won the civil war. He was followed by Severus Alexander (218–222). Neither emperor is much mentioned in Egyptian records.

After Decius died, Trebonianus Gallus (251–253) was recognized as emperor. In 253, an embassy from Meroë visited the Romans. Both Trebonianus Gallus and Aemilianus (253) had coins minted in their names in Alexandria. During the reigns of Valerian (253–260) and Gallienus (253–268), the empire was unstable. Valerian was captured by the Sasanian Empire in 260. After this, the army declared Quietus and Macrianus (260–261) emperors. They were recognized in Egypt. When they were overthrown, the Alexandrians declared Lucius Mussius Aemilianus, the governor, as their new emperor. He had success against the Blemmyes. But by August 262, Alexandria was destroyed, losing two-thirds of its people in street fights. Aemilianus was defeated.

There were many revolts in the 200s. Under Decius, Christians were persecuted again, but their religion continued to spread. The governor of Egypt, Mussius Aemilianus, first supported other rebels. Later, in 261, he became a rebel himself but was defeated.

Egypt came under the rule of Zenobia during the time of the Palmyrene Empire. Her state fought Rome. Egypt held out against Aurelian (270–275). His forces captured Egypt by late 271. However, in 272, Alexandria and Palmyra revolted again. Aurelian besieged Alexandria, and the rebel leader Firmus killed himself. Emperor Probus (276–282) defeated the Blemmyes who attacked Upper Egypt.

Later Roman Egypt (4th–7th Centuries)

Coptos revolted in 293 and was destroyed by Emperor Diocletian's junior co-emperor, Galerius (293–311). Diocletian's reforms divided the empire into more provinces. Egypt was split, with the Thebaid becoming its own province. Financial and tax reforms were made in Egypt in 297. Egyptian money was brought in line with the rest of the empire. The role of the governor was divided between a civilian governor and a military leader.

In 297, Domitius Domitianus led a revolt and made himself emperor. Diocletian captured Alexandria from them after an eight-month siege. "Pompey's Pillar" was put up in his honor in Alexandria. Diocletian then traveled through Egypt to Philae, where new gates were built. He gave the Dodekaschoinos region to the Noba people. They were paid by the Romans to defend the border from the Blemmyes. Diocletian's second visit to Egypt in 302 involved giving bread to Alexandrians. He also took action against followers of Manichaeism. The next year, Diocletian started a persecution against Christians. This persecution was very harsh. It ended in 311.

In 313, Licinius (308–324) and Constantine the Great (306–337) issued the Edict of Milan. This gave Christianity official recognition. The tax system was reformed. The former soldier Pachomius the Great became a Christian in 313. Constantine may have planned to visit Egypt in 325. The Nicene Creed united most of the Christian Church against the Arianism promoted by the Egyptian bishop Arius. It supported the ideas of another Egyptian bishop, Athanasius of Alexandria. In 330, the Christian monk Macarius of Egypt founded his monastery in the desert.

On February 24, 391, Emperor Theodosius the Great (379–395) banned sacrifices and worship at temples throughout the empire. On June 16, he reissued the ban specifically for Alexandria and Egypt.

The bishop, Theophilus of Alexandria, caused unrest against pagans. He tried to turn a temple into a church and found Christian relics. These were paraded through the streets. Pagans had to hide in the Serapeum. The Christian mob loyal to Theophilus looted the Serapeum. It was later turned into a church. The Serapeum of Canopus was also looted. Many pagan scholars fled Egypt.

The long reign of Theodosius II (402–450) saw unrest caused by Bishop Cyril of Alexandria. He was against the ideas of Nestorius, the bishop of Constantinople. Cyril's group won, and Nestorius was banished in 435. The power of Alexandria's bishop reached its peak in 449.

The Blemmyes continued to attack Roman Egypt. In 451, Emperor Marcian (450–457) made a peace treaty with them. It allowed them to use the temple at Philae annually.

However, Marcian also called the 451 Council of Chalcedon. This council overturned the previous decisions and condemned Dioscorus, sending him into exile. The lasting split between the Coptic Church and the state church of the Roman Empire dates from this time. Proterius was appointed bishop instead. When Alexandrians heard of the new emperor, they killed Proterius and chose their own bishop, Timothy II.

The Sasanian Empire invaded the Nile Delta during Anastasius I's reign (491–518). But the Sasanian army retreated. In the early 500s, the Blemmyes attacked Upper Egypt again. Emperor Justinian I (527–565) and his wife, Theodora, tried to convert the Noba to Christianity. The Noba adopted the Miaphysite beliefs of the Coptic Church. They helped the Roman army conquer the pagan Blemmyes. In 543, the general Narses confiscated the cult statues of Philae, closed the temple, and imprisoned its priests. In 577, the defenses at Philae had to be rebuilt to stop Blemmyes attacks.

Constantine the Great also founded Constantinople as a new capital for the Roman Empire. In the 300s, the Empire was divided into two. Egypt became part of the Eastern Empire, with its capital at Constantinople. Latin was never strong in Egypt, and Greek remained the main language of government and learning. During the 400s and 500s, the Eastern Roman Empire, also called the Byzantine Empire, slowly became a Christian state. Its culture was very different from its pagan past.

The Eastern Empire became more "oriental" as its ties to the old Greek-Roman world faded. The Greek system of local government by citizens disappeared. Offices, with new Greek-Byzantine names, were almost passed down through wealthy land-owning families. Alexandria, the empire's second city, continued to be a center of religious arguments and violence.

Egypt remained an important economic center for the Empire. It provided much of its food and manufactured goods. It also continued to be a major center of learning. It supplied the needs of the Byzantine Empire and the Mediterranean. The reign of Justinian (527–565) saw the Empire recapture Rome and much of Italy. But these successes left the empire's eastern side open to attack. Egypt, the empire's "bread basket," now lacked protection.

Sasanian Persian Invasion (619 AD)

The Sasanian conquest of Egypt, starting in AD 618 or 619, was one of the last big wins for the Sassanid Empire against the Byzantine Empire. From 619 to 628, they ruled Egypt again. The last time was under the Achaemenids. Khosrow II started this war to get revenge for the killing of Emperor Maurice. He had early successes, taking Jerusalem (614) and Alexandria (619).

A Byzantine counterattack by Emperor Heraclius in 622 changed the war. The war ended when Khosrow fell on February 25, 628. The Egyptians did not like the emperor in Constantinople and did not fight much. Khosrow's son, Kavadh II, made a peace treaty. It returned the conquered lands to the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Sasanian conquest allowed Miaphysitism to become more open in Egypt. When Emperor Heraclius restored Roman rule in 629, the Miaphysites were persecuted. Their church leader was expelled. Egypt was thus separated from the Empire both religiously and politically when a new invader arrived.

Arab Islamic Conquest (639–646 AD)

An army of 4,000 Arabs led by Amr Ibn Al-Aas was sent by the Caliph Umar. Their goal was to spread Islamic rule west. The Arabs entered Egypt from Palestine in December 639. They quickly moved into the Nile Delta. The Roman armies retreated into walled towns. They held out for a year or more.

The Arabs called for more soldiers. In April 641, they besieged and captured Alexandria. The Byzantines gathered a fleet to retake Egypt. They won back Alexandria in 645. But the Muslims took the city again in 646. This completed the Muslim conquest of Egypt. 40,000 civilians were taken to Constantinople by the imperial fleet. This ended 975 years of Greek-Roman rule over Egypt.

Images for kids

-

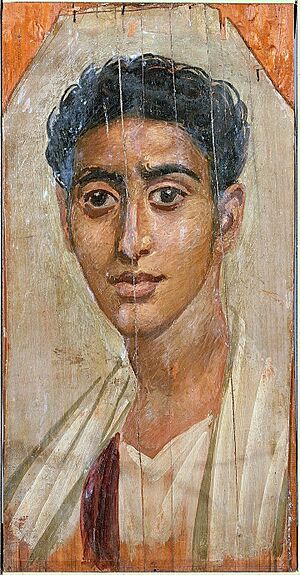

Mummy Mask of a Man, early 1st century AD, 72.57, Brooklyn Museum

-

Canopic jar from the 3rd or 4th century (National Archaeological Museum, Florence)

-

Funerary masks uncovered in Faiyum, 1st century.

-

2nd-century statuette of Horus as Roman general (Louvre)

-

1st–4th-century statuette of Horus as a Roman soldier (Louvre)

-

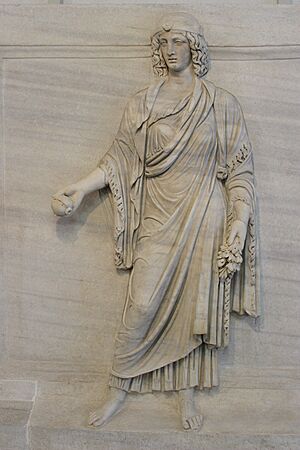

2nd-century statuette of Isis–Aphrodite from Lower Egypt (Louvre)

-

1st–4th-century statuette of Isis lactans (Louvre)

-

2nd/3rd-century mosaic of Anubis from Ariminum (Museo della Città, Rimini)

-

6th- or 7th-century Christian sandstone grave stela (Luxor Museum)

-

6th- or 7th-century Christian sandstone stela (Luxor Museum)

-

6th- or 7th-century Christian sandstone relief (Luxor Museum)

-

Zenobia coin reporting her title as queen of Egypt (Augusta), and showing her diademed and draped bust on a crescent. The obverse shows a standing figure of Ivno Regina (Juno) holding a patera in her right hand and a sceptre in her left hand, with a peacock at her feet and a brilliant star on the left.

See also

- Roman pharaoh