History of sugar facts for kids

The story of sugar is a long and sweet one! For thousands of years, people have enjoyed sugar. It started as a wild plant and became a common food around the world.

The journey of sugar can be divided into five main parts:

- First, people learned to get juice from the sugarcane plant. This happened in tropical India and Southeast Asia around 4,000 BC.

- Next, about 2,000 years ago, people in India figured out how to make sugar granules from sugarcane juice. They also improved how to make these sugar crystals cleaner.

- Then, growing sugarcane and making sugar spread to the medieval Islamic world. They also made some improvements to the process.

- After that, sugar farming and production moved to the West Indies and parts of the Americas starting in the 1500s. Production methods got much better from the 1600s to the 1800s.

- Finally, in the 1800s and 1900s, new types of sugar like beet sugar and high-fructose corn syrup were developed.

Sugar was first made from sugarcane plants in India after the first century AD. The word "sugar" likely comes from the ancient Indian language Sanskrit. The word śarkarā meant "ground or candied sugar," or originally "grit, gravel." Old Indian writings from between 1500 and 500 BC first mention growing sugarcane and making sugar in the Bengal region of India.

By the end of the Middle Ages, sugar was known worldwide. It was very expensive and seen as a "fine spice." But after about 1500, new technologies and sources from the Americas made sugar much cheaper and more widely available.

Contents

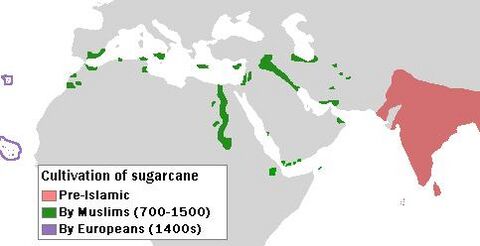

How Sugarcane Spread Around the World

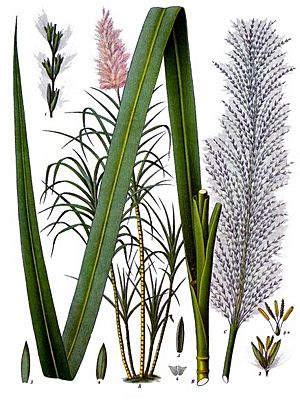

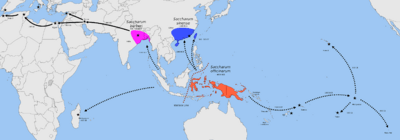

Sugarcane was first grown in two main places. One type, Saccharum officinarum, was first grown by Papuans in New Guinea. Another type, Saccharum sinense, was first grown by Austronesians in Taiwan and southern China. At first, Papuans and Austronesians mostly used sugarcane to feed their pigs. The way both types of sugarcane spread is closely connected to the journeys of the Austronesian peoples. Saccharum barberi was only grown in India after S. officinarum arrived there.

Saccharum officinarum was first grown in New Guinea and the islands east of the Wallace Line by Papuans. This area is still where many different types of this sugarcane grow. Around 6,000 years ago, Papuans started to breed it from the wild plant Saccharum robustum. From New Guinea, it spread west to Island Southeast Asia after people met Austronesians. There, it mixed with another type called Saccharum spontaneum.

The second place where sugarcane was first grown was mainland southern China and Taiwan. Here, S. sinense was a main crop for the Austronesian peoples. Words for sugarcane exist in the ancient Proto-Austronesian languages in Taiwan. It was one of the first major crops for the Austronesian peoples from at least 5,500 years ago. The sweeter S. officinarum may have slowly replaced it in many places across Island Southeast Asia.

From Island Southeast Asia, S. officinarum was carried east into Polynesia and Micronesia by Austronesian sailors. They took it as a canoe plant around 3,500 years ago. It also spread west and north around 3,000 years ago to China and India by Austronesian traders. There, it mixed further with Saccharum sinense and Saccharum barberi. From there, it spread even further into western Eurasia and the Mediterranean region.

India, where people learned to refine cane juice into sugar crystals, was often visited by groups from other empires, like China. They came to learn about growing sugarcane and refining sugar. By the 500s AD, sugar farming and processing had reached Persia. In the Mediterranean, sugarcane might have been brought during the Arab expansion in the Middle Ages. "Wherever they went, the medieval Arabs brought with them sugar, the product and the technology of its production."

Spanish and Portuguese explorers and conquerors brought sugar southwest of Iberia in the 1400s. Henry the Navigator brought sugarcane to Madeira in 1425. The Spanish, after taking control of the Canary Islands, also brought sugarcane there. In 1493, on his second trip, Christopher Columbus took sugarcane seedlings to the New World, especially to Hispaniola.

Early Use of Sugarcane in India

Sugarcane first grew in tropical India and Southeast Asia. Different types likely came from different places. For example, S. barberi came from India, and S. edule and S. officinarum came from New Guinea. At first, people just chewed raw sugarcane to enjoy its sweetness. People in India discovered how to make sugar into crystals during the Gupta dynasty, around 350 AD. However, old Indian writings from the 2nd century AD suggest that refined sugar was already being made in India.

Indian sailors, who ate clarified butter and sugar, carried sugar along different trade routes. Buddhist monks traveling to China brought sugar crystallization methods with them. During the rule of Harsha (606–647) in North India, Indian messengers in Tang China taught sugarcane farming methods. This happened after Emperor Taizong of Tang (626–649) showed interest in sugar. China soon started its first sugarcane farms in the 600s. Chinese records confirm at least two trips to India, starting in 647 AD, to get technology for sugar refining. In India, Iran, and China, sugar became a common ingredient in cooking and desserts.

Early ways of refining sugar involved grinding or pounding the cane to get the juice. Then, they would boil the juice down or dry it in the sun to get sugary solids that looked like gravel. The Sanskrit word for "sugar" (sharkara) also means "gravel" or "sand." In Persian, "shakar" (شکر) means sweetening seeds. Similarly, the Chinese use the term "gravel sugar" (砂糖) for what we call "table sugar."

In 1792, sugar prices went up a lot in Great Britain. On March 15, 1792, British ministers told the British parliament about making refined sugar in British India. Lieutenant J. Paterson reported that refined sugar could be made in India with many benefits and much cheaper than in the West Indies.

Sugar in the Medieval Muslim World and Europe

Ancient Greeks and Romans knew about sugar, but only as a medicine, not as food. For example, the Greek doctor Dioscorides wrote in the 1st century AD: "There is a kind of honey called sakcharon [sugar] found in reeds in India and Yemen. It is like salt and breaks easily. It is good dissolved in water for the intestines and stomach, and can help a painful bladder and kidneys." Pliny the Elder, a Roman from the 1st century AD, also described sugar as medicine: "Sugar is also made in Arabia, but Indian sugar is better. It is a type of honey found in cane, white like gum, and it crunches when you chew it. It comes in lumps the size of a hazelnut. Sugar is used only for medical purposes."

During the Middle Ages, Arab business people learned sugar production methods from India and made the industry bigger. Medieval Arabs sometimes set up large plantations with sugar mills or refineries on site. The sugarcane plant needs a lot of water and heat to grow well. It spread throughout the medieval Arab world using artificial irrigation. Sugarcane was first grown widely in medieval Southern Europe during Arab rule in Sicily, starting around the 800s. Besides Sicily, Al-Andalus (in what is now southern Spain) was an important place for sugar production, starting by the 900s.

From the Arab world, sugar was sent all over Europe. More sugar was imported in later medieval centuries. This is shown by more mentions of sugar consumption in European writings. But cane sugar remained an expensive import. Its price per pound in England in the 1300s and 1400s was about as high as spices from tropical Asia. These spices, like mace, ginger, cloves, and pepper, had to be brought across the Indian Ocean.

Clive Ponting explains how sugarcane farming spread. It was brought to Mesopotamia, then the Levant and the islands of the eastern Mediterranean, like Cyprus, by the 900s. He also notes that it spread along the coast of East Africa to reach Zanzibar.

Crusaders brought sugar home to Europe after their trips to the Holy Land. There, they saw caravans carrying what they called "sweet salt." In the early 1100s, Venice got some villages near Tyre and set up farms to produce sugar for Europe. It became another sweetener besides honey. Crusade writer William of Tyre, writing in the late 1100s, called sugar "a most precious product, very necessary for the use and health of mankind." The first time sugar is mentioned in English writings is in the late 1200s.

Ponting describes how early European sugar businesses relied on forced labor: The main challenge with making sugar was that it needed a lot of hard work for both growing and processing. Raw cane was very heavy and bulky, making it costly to move. So, each farm needed its own factory. There, the cane had to be crushed to get the juice, which was then boiled to make it thicker. These were very hard and long tasks. However, once processed, sugar was very valuable for its size. It could be traded over long distances by ship for a good profit. The European sugar industry really began after the Middle East was lost to a stronger Islamic world. Production moved to Cyprus, controlled by Crusader nobles and Venetian traders. Local people on Cyprus mostly grew their own food and few wanted to work on sugar farms. So, the owners brought in people from the Black Sea area (and some from Africa) who were forced to work. The demand and production were low, so the trade in forced laborers was small, about a thousand people a year. It wasn't much larger when sugar production started in Sicily.

In the Atlantic Ocean (the Canaries, Madeira, and the Cape Verde Islands), after the first use of timber and raw materials, it quickly became clear that sugar production would be the most profitable way to make money from these new lands. The problem was the hard work needed, because Europeans refused to work except as supervisors. The solution was to bring in people from Africa who were forced to work. This trade began to grow significantly in the 1440s.

In the 1390s, a better press was invented. This machine doubled the amount of juice taken from sugarcane. It helped sugar farms expand economically to Andalusia and the Algarve. It started in Madeira in 1455, with advice from Sicily and money from Genoa for the mills. Madeira's easy access attracted traders from Genoa and Flanders. They wanted to avoid Venice's control over sugar trade. "By 1480, Antwerp had about seventy ships involved in the Madeira sugar trade. Refining and distribution were centered in Antwerp." In the 1480s, sugar production spread to the Canary Islands. By the 1490s, Madeira had become a bigger sugar producer than Cyprus. African people who were forced into labor also worked on sugar farms in the Kingdom of Castile around Valencia.

Sugar Farming in the New World

The Portuguese brought sugar to Brazil. By 1540, there were 800 cane sugar mills on Santa Catarina Island. There were another 2,000 on the north coast of Brazil, Demarara, and Surinam. The first sugar harvest happened in Hispaniola in 1501. Many sugar mills were built in Cuba and Jamaica by the 1520s.

The roughly 3,000 small sugar mills built before 1550 in the New World created a huge need for cast iron gears, levers, axles, and other tools. Special skills in mold-making and iron casting developed in Europe because sugar production grew so much. Building sugar mills helped develop the technical skills needed for an early industrial revolution in the early 1600s.

After 1625, the Dutch moved sugarcane from South America to the Caribbean islands. It was grown from Barbados to the Virgin Islands.

People at the time often compared sugar's value to expensive goods like musk, pearls, and spices. Sugar prices slowly went down as more places in the European colonies started producing it. Once only for the rich, sugar became more common for everyone. Sugar production increased in the North American colonies, in Cuba, and in Brazil. The workers at first included European indentured servants and local Native American people, as well as African people forced into labor. However, European diseases like smallpox and African ones like malaria and yellow fever soon reduced the number of local Native Americans. Europeans were also very likely to get malaria and yellow fever. The supply of indentured servants was limited. African enslaved people became the main source of plantation workers. This was because they were more resistant to malaria and yellow fever, and because the supply of enslaved people was large on the African coast.

During the 1700s, sugar became incredibly popular. Great Britain, for example, used five times more sugar in 1770 than in 1710. By 1750, sugar was "the most valuable product in European trade." It made up a fifth of all European imports. In the last decades of the century, four-fifths of the sugar came from British and French colonies in the West Indies. From the 1740s until the 1820s, sugar was Britain's most valuable import.

The sugar market went through many booms. The higher demand and production of sugar happened largely because Europeans changed their eating habits. For example, they started eating much more jams, candy, tea, coffee, cocoa, processed foods, and other sweet things. The Caribbean islands took advantage of this trend and produced even more sugar. In fact, they made up to ninety percent of the sugar that western Europeans ate. Some islands were more successful than others. In Barbados and the British Leeward Islands, sugar made up 93% and 97% of exports, respectively.

Farmers later started finding ways to produce even more. For example, they used better farming methods. They also developed more advanced mills and used better types of sugarcane. In the 1700s, "the French colonies were the most successful, especially Saint-Domingue. Better irrigation, water-power, and machinery, along with focusing on newer types of sugar, increased profits." Despite these improvements, the price of sugar reached very high levels, especially during events like the revolt against the Dutch and the Napoleonic Wars. Sugar remained in high demand, and the island farmers knew how to profit from the situation.

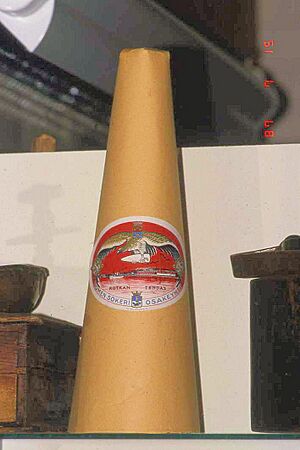

As Europeans set up sugar farms on the larger Caribbean islands, prices in Europe fell. By the 1700s, people from all parts of society commonly used this product, which used to be a luxury. At first, most sugar in Britain went into tea. But later, confectionery and chocolates became very popular. Many Britons (especially children) also ate jams. Suppliers usually sold sugar in the shape of a sugarloaf. Customers needed sugar nips, a tool like pliers, to break off pieces.

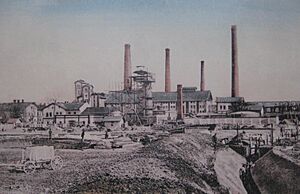

Sugarcane quickly uses up the nutrients in the soil where it grows. So, farmers started using larger islands with fresher soil in the 1800s as the demand for sugar in Europe kept growing. "Average sugar use in Britain went from four pounds per person in 1700 to eighteen pounds in 1800, thirty-six pounds by 1850, and over one hundred pounds by the 1900s." In the 1800s, Cuba became the richest land in the Caribbean. Sugar was its main crop. This was because Cuba was the only major island landmass without mountains. Instead, almost three-quarters of its land was a rolling plain, perfect for planting crops. Cuba also did better than other islands because Cubans used better methods for harvesting sugar crops. They adopted modern milling methods like watermills, enclosed furnaces, steam engines, and vacuum pans. All these technologies made production higher. Cuba also kept using forced labor longer than most other Caribbean islands.

After the Haitian Revolution created the independent country of Haiti, sugar production there went down. Cuba then replaced Saint-Domingue as the world's largest producer.

Sugar production, which was already strong in Brazil, spread to other parts of South America. It also went to newer European colonies in Africa and the Pacific. It became very important in Fiji. Mauritius, Natal, and Queensland in Australia started growing sugar. The older and newer sugar production areas now tended to use indentured labor instead of forced labor. Workers were "shipped across the world... and... held in conditions of near slavery for up to ten years..." In the second half of the 1800s, over 450,000 indentured laborers went from India to the British West Indies. Others went to Natal, Mauritius, and Fiji (where they became most of the population). In Queensland, workers from the Pacific islands were moved in. In Hawaii, they came from China and Japan. The Dutch moved many people from Java to Surinam. It is often said that sugar farms would not have done so well without the help of African people forced into labor. In Colombia, sugar planting started very early. Business owners brought many African people who were forced into labor to work the fields. The industrialization of the Colombian sugar industry began in 1901. This was with the establishment of Manuelita, the first steam-powered sugar mill in South America, by Latvian Jewish immigrant James Martin Eder.

The Rise of Beet Sugar

Sugar was a luxury in Europe until the early 1800s. Then, it became more widely available because of the growth of beet sugar in Prussia (part of modern Germany), and later in France under Napoleon. Beet sugar was a German invention. In 1747, Andreas Sigismund Marggraf announced he had found sugar in beets. He also created a way to get it out using alcohol. Marggraf's student, Franz Karl Achard, developed an affordable industrial method to get pure sugar from beets in the late 1700s. Achard first made beet sugar in 1783 in Kaulsdorf. In 1801, with support from King Frederick William III of Prussia (who ruled from 1797–1840), the world's first beet sugar factory was built in Cunern, Silesia (then part of Prussia). This factory operated from 1801 until it was destroyed during the Napoleonic Wars (around 1802–1815), though it never made a profit.

The work of Marggraf and Achard was the start of the sugar industry in Europe. It also led to the modern sugar industry in general. Sugar was no longer a luxury product made almost only in warm places.

In France, Napoleon was cut off from Caribbean sugar imports by a British blockade. He also did not want to fund British merchants. So, he banned sugar imports in 1813. He ordered 32,000 hectares (about 79,000 acres) of land to be planted with beetroot. A beet sugar industry grew, especially after Jean-Baptiste Quéruel made the process more industrial for Benjamin Delessert.

The United Kingdom Beetroot Sugar Association was started in 1832. But efforts to grow sugar beet in the UK were not very successful at first. Sugar beets made up about two-thirds of the world's sugar production in 1899. 46% of British sugar came from Germany and Austria. Sugar prices in Britain dropped sharply towards the end of the 1800s. The British Sugar Beet Society was set up in 1915. By 1930, there were 17 factories in England and one in Scotland. They were supported by the British Sugar (Subsidy) Act 1925. By 1935, homegrown sugar made up 27.6% of British sugar use. By 1929, 109,201 people worked in the British sugar beet industry, with about 25,000 more temporary workers.

How Sugar Production Became More Mechanized

Starting in the late 1700s, making sugar became more and more machine-powered. The steam engine first powered a sugar mill in Jamaica in 1768. Soon after, steam replaced direct fire for heating in the process.

In 1813, the British chemist Edward Charles Howard invented a way to refine sugar. It involved boiling the cane juice in a closed container heated by steam and under a partial vacuum. At lower pressure, water boils at a lower temperature. This invention saved fuel and reduced the amount of sugar lost by caramelization. More fuel savings came from the multiple-effect evaporator. This was designed by the United States engineer Norbert Rillieux (possibly as early as the 1820s, with the first working model in 1845). This system had a series of vacuum pans, each with lower pressure than the one before it. The steam from each pan heated the next, wasting very little heat. Modern industries still use multiple-effect evaporators to remove water.

The process of separating sugar from molasses also got mechanical help. David Weston first used the centrifuge for this task in Hawaii in 1852.

Other Sweeteners

In the United States and Japan, high-fructose corn syrup has replaced sugar in some products. This is especially true in soft drinks and processed foods.

The process to make high-fructose corn syrup was first developed by Richard O. Marshall and Earl R. Kooi in 1957. The industrial production process was improved by Dr. Y. Takasaki in Japan between 1965 and 1970. High-fructose corn syrup was quickly added to many processed foods and soft drinks in the United States from about 1975 to 1985.

A system of sugar tariffs (taxes) and quotas (limits) in the United States in 1977 greatly increased the cost of imported sugar. U.S. producers looked for cheaper sources. High-fructose corn syrup, made from corn, was more affordable. This is because the U.S. price of sugar is twice the global price, and the price of corn is kept low with government help to farmers. High-fructose corn syrup became a good substitute. Most American food and drink makers prefer it over cane sugar. Soft drink companies like Coca-Cola and Pepsi use sugar in other countries, but switched to high-fructose corn syrup in the United States in 1984.

The average American ate about 37.8 kg (83.3 lb) of high-fructose corn syrup in 2008. They ate about 46.7 kg (103 lb) of regular sugar.

In recent years, some people have suggested that more high-fructose corn syrup in processed foods might be linked to various health problems. These include metabolic syndrome, hypertension (high blood pressure), dyslipidemia (unhealthy fat levels in blood), hepatic steatosis (fatty liver), insulin resistance, and obesity. However, there is little proof that high-fructose corn syrup is unhealthier, calorie for calorie, than regular sugar or other simple sugars. The amount of fructose and the fructose-to-glucose ratio in high-fructose corn syrup are not very different from clear apple juice. Some researchers think that fructose might cause more fat to form than other simple sugars. However, most common types of high-fructose corn syrup have almost equal amounts of fructose and glucose, just like regular sugar. So, they should be processed by the body in the same way after the first steps of sugar metabolism. At the very least, the growing use of high-fructose corn syrup has certainly led to more added sugar calories in food. This could reasonably increase the number of people with these and other diseases.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del azúcar para niños

In Spanish: Historia del azúcar para niños

- Sugar Cane and Rum Museum

- Castillo Serrallés

- Hacienda Mercedita

- Food history

- Sugar industry

- Sugar Museum (Berlin)